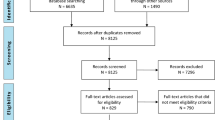

Abstract

Purpose of Review

To provide a resource for providers that may be involved in the diagnosis and management of infant non-accidental trauma (NAT).

Recent Findings

Infants are more likely to both suffer from physical abuse and die from their subsequent injuries. There are missed opportunities among providers for recognizing sentinel injuries. Minority children are overrepresented in the reporting of child maltreatment, and there is systemic bias in the evaluation and treatment of minority victims of child abuse.

Summary

Unfortunately, no single, primary preventative intervention has been conclusively shown to reduce the incidence of child maltreatment. Standardized algorithms for NAT screening have been shown to increase the bias-free utilization of NAT evaluations. Every healthcare provider that interacts with children has a responsibility to recognize warning signs of NAT, be able to initiate the evaluation for suspected NAT, and understand their role as a mandatory reporter.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There were over 650,000 substantiated reports of child maltreatment to the various child protective service (CPS) agencies across the USA in 2019, and around 1,800 deaths attributable to abuse or neglect [1, 2]. This burden is carried disproportionately by infants (children < 1 year of age) accounting for nearly half of all abuse-related deaths in the USA [2]. In fact, non-accidental trauma (NAT) is an independent predictor of mortality in infants [3] and older children [4•, 5] compared with other mechanisms of traumatic injury. However, mortality is only one small aspect of the consequences of child maltreatment. NAT results in longer and costlier hospital stays [6], and the lifetime societal costs for a single year of child abuse cases number in the billions [7•]. In addition to the direct harm of physical injury, traumatic events in childhood have been shown to lead to long-term issues with attachment as well as alteration of the biologic responses to stress and early brain development [8]. There is also evidence that some victims of abuse may go on to become abusers themselves, perpetuating the cycle of maltreatment [9].

Every clinician whose practice includes taking care of children has a responsibility to recognize the warning signs of child maltreatment and initiate the diagnosis and treatment of suspected child abuse. This starts with the most vulnerable and the most disproportionately affected pediatric age group—infants. The goal of this manuscript is to provide a summary of recent literature related to the epidemiology, evaluation, and diagnosis of NAT specific for the infant age group. Furthermore, we provide an update on current, evidence-based strategies for NAT prevention.

Epidemiology

Among the spectrum of pediatric age groups, infants are more disproportionately affected by NAT. While the overall incidence of abuse in children is 6 per 100,000 children, infants have a nearly tenfold higher incidence at 58 per 100,000 children [10]. Infants are also three times more likely to die compared to older children as a result of NAT [2]. These numbers almost certainly underrepresent the total number of infants affected by maltreatment because of known issues with underreporting [11,12,13].

While individual risk factors for child maltreatment change depending on the cross section of patients examined, decreased parental age, decreased gestational age or weight, parents with pre-existing social concerns, less access to perinatal care or resources, parental smoking or substance abuse, households with a history of domestic violence, and poverty have all been implicated for increasing the risk for NAT [14,15,16]. Furthermore, victims of NAT from neighborhoods with a lower median income (indicators of lower socioeconomic status) or with government-based healthcare were more likely to die from their injuries, regardless of injury severity [17, 18].

There are significant disparities in the management, reporting, and outcomes of injured children related to race/ethnicity. While Caucasian children make up the largest portion of children diagnosed with NAT, Black children are disproportionately represented [3, 18]. A recent analysis of the 2018 National Child Abuse and Neglect Data System (NCAND) revealed that Black communities are the most overrepresented community for physical, sexual, and psychological abuse of children, followed by multiracial, Pacific Islander, and Native American [19•]. When it comes to physical abuse, Black children are overrepresented in 86% of US states [19•]. And previous studies show an increase in abuse-related mortality among Black infants regardless of socioeconomic status [20]. Though, this information needs to take into account that suspicion and reporting are biased against Black caregivers due to implicit and explicit biases, and systemic and structural racism. As such, Black caregivers are more likely to be reported to CPS, and their children are more likely to undergo workups for NAT, including head computed tomography (CT) scan and skeletal surveys [21, 22]. Depending on the state of origin, children from Latinx-identified communities are also more likely to be victims of abuse [19•]. While it is beyond the scope of this paper to discuss the societal and policy failures that have led to these disparities, there is a clearly biased overrepresentation of minority communities in the reporting, incidence, and severity of NAT.

Evaluation and Recognition of NAT

Detecting abuse early has the potential to be lifesaving for that child, and siblings in the same home, and there is evidence to suggest that physicians may be missing sentinel events or injuries [11, 13]. The possibility of NAT should be considered by providers who evaluate injured children. Infants are non-verbal and are unable to provide a history of events, which makes them a challenging group of patients to evaluate after injury. Failure to recognize an injury secondary to NAT comes with a cost—victims of recurrent NAT are more likely to die from their subsequent injuries [23]. However, it is important to remember that there is no constellation of injuries or findings that are pathognomonic for the diagnosis of NAT.

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) has released a framework for the initial interview and examination of children with suspicious injuries [24••]. The entire encounter should be thorough and well documented by the provider. The evaluation of an infant with suspicious injuries starts with a detailed history of both the events and the social situation of the caregivers, which can be obtained with a non-adversarial or non-accusatory interaction. It can be insightful to begin by understanding the circumstances of the pregnancy (i.e., planned vs. unplanned and wanted vs. unwanted), history of abuse/child protective services (CPS) involvement with the family, patterns of discipline for the children, any substance abuse, any current or prior intimate partner violence; family history of hematologic, connective tissue, or bone disorders; and social/financial stressors facing the family. The circumstances of the injury should also be thoroughly explored with the caregivers. Potential warning signs include vague/absent explanations for concerning injuries, denial of trauma in an infant with injuries, unexplained delay in seeking medical care, stories that change significantly between caregivers, or explanations that are inconsistent with the constellation of injuries. In non-ambulatory infants (typically 0–8 months), any unexplained external signs of injury should be carefully considered for the possibility of NAT [24••]

The physical exam of the infant should then be done completely unclothed and should start with assessment of expected/presenting developmental behaviors and growth curves. Abuse and neglect can frequently coincide with developmental and physical growth restrictions, or a rapidly increasing head circumference [25]. Next, the provider moves to a thorough head-to-toe examination of the child starting with any cutaneous findings, paying particular attention to more inconspicuous areas such as the ears, scalp, axillae, hands, feet, buttocks, and genitals. It is important to assess bruising within the context of a child’s mobility as noted above. While 40–90% of children may present with bruising, this is true for < 1% of babies less than 9 months of age who have not yet reached the crawling or cruising stages of development [26,27,28]. Therefore, significant bruising in the infant should prompt further evaluation for abuse, while also evaluating for an early manifestation of a bleeding disorder. In children of all ages, patterned bruising, bruising over soft tissue areas (abdomen, buttocks, genitals, ears, thighs, etc.), or bruising inconsistent with the reported story should raise concern and warrant further evaluation. Historically, bruises of varying ages were embraced to be an important consideration for providers; however, there is evidence that providers are unable to accurately date bruises based on exam alone [29]. A thorough oral exam should also be completed looking for signs of intraoral trauma, particularly torn or injured frenula. While it is outside the scope of this article, burn evaluation should be approached in a similar manner to bruising with careful attention to the reported source of the burn, details of how the burn trauma was caused, timing of exposure, depth and size of the burn, any first aid applied, and careful attention to patterned and circumferential burns. Infants with significant burns should be considered for early transfer to a center specializing in burn care [30].

In suspected cases of NAT, a determination needs to be made about the utility of radiologic imaging studies to diagnose and locate injuries. The American College of Radiology (ACR) published appropriate use criteria in 2017 for the evaluation of NAT that is based on the age of the child in question and the presenting symptoms/physical exam [31••]. For children < 24 months of age, a skeletal survey is recommended as the initial screening imaging evaluation. For all infants < 6 months, and any child 6 months of age or older with central nervous system signs or symptoms, apnea, unexplained emesis, external head/face injuries, or a skull fracture, the AAP and ACR suggest that screening with a non-contrast head CT is appropriate. Non-contrast magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain and cervical spine is recommended if initial CT head imaging shows intracranial injury. Finally, for any child with suspected thoracic or abdominal injuries (bruising, tenderness, or elevated liver/pancreatic enzymes), intravenous contrast CT imaging of the abdomen and pelvis is indicated to rule out occult solid organ and intestinal trauma [32, 33]. Abdominal ultrasound and plain film radiographs are insufficient modalities to rule out thoracic or abdominal trauma. Additional imaging of the chest, abdomen, and head by CT, and MRI of the brain may be indicated depending on the clinical scenario. It is recommended that most initial skeletal surveys be accompanied by a modified follow-up second skeletal survey 10–14 days later [34, 35].

Skeletal surveys serve as one of the most important diagnostic evaluations of suspected NAT. However, in the absence of physical exam findings, the use of skeletal surveys is largely dependent on the level of provider suspicion, which can serve as a significant source of bias for NAT. In addition, for children < 6 months of age, head imaging using either CT or non-contrast MRI is recommended. Head ultrasound is an insufficient modality to screen for NAT in these infants.

A thorough ophthalmologic exam should also be performed on infants with suspected NAT, especially when abusive head trauma (AHT) is a consideration. Ideally, a dilated exam should be performed by an ophthalmologist with the appropriate equipment to fully examine the retina and document any pertinent findings. While retinal hemorrhages can occur with accidental mechanisms of head trauma, multiple, bilateral, and multilayered retinal hemorrhages and retinoschisis are increasingly concerning for AHT [36].

After the initial evaluation, appropriate actions should be taken to treat any identified injuries, the infant should be triaged to a facility with the appropriate resources for NAT, and all medical providers in the USA are mandated by law to make a referral to local CPS and/or law enforcement for suspected child maltreatment. Finally, if admission is indicated, it should be a team that is familiar and comfortable with the complexities of providing care to abused children, with an immediate consultation to a child abuse pediatrics expert, where one is available [37].

Table 1 Evaluation of suspected child abuse.

Standardized NAT Screening

A recent survey demonstrated strong support among healthcare providers for the reduction of practice variation in regard to NAT workup [38]. However, this same survey demonstrated pessimism among healthcare providers that there is an effective method for achieving that goal and that practice variation may be justified because of clinical differences—highlighting some of the challenges of implementing standardization. Only 57% of providers report using a screening tool for the detection of NAT, regardless of practice location [39]. And, while there is larger support for the use of management guidelines (75%), there is also more variability; pediatric trauma centers were more likely to use a management protocol than adult trauma centers (78% vs. 38%, p < 0.04). The argument for standardization in NAT workup centers around two key issues: missed opportunities for intervention and provider bias.

Thorpe et al. demonstrated that among children with a confirmed diagnosis of abuse, one-third of these abused children had at least one visit in the prior 6 months where the diagnosis of abuse should have been suspected [40]. Sheets et al. similarly found that, among abused infants, 27.5% had a previous sentinel injury and that the provider was aware of this injury in approximately 40% of cases [13]. Furthermore, even when abuse is suspected, critical components of the social history and documentation of pertinent exam findings may be inadequate in the absence of a specific management protocol and documentation standards [41].

Unfortunately, as noted previously, differences in evaluation and treatment are further influenced by race and socioeconomic status. Black children and children of lower socioeconomic status are more likely to undergo a skeletal survey, despite a potentially lower likelihood of positive surveys in Black children [22, 42]. Among young children hospitalized to the intensive care unit for acute head injuries, minority patients were two times more likely to be evaluated and reported for suspected abuse than white/non-Hispanic patients [43].

The implementation of a standardized protocol for the evaluation of suspected NAT has been shown to increase the number of patients screened, ensure that children with higher risk of abuse have higher rates of evaluation, and remove socioeconomic bias regarding evaluation [44, 45]. This holds true even for small interventions. A simple clinical pathway that automatically involved a child abuse team and social worker if a child had one of ten concerning injuries was found to remove socioeconomic bias [46]. While no authors have effectively demonstrated a reduction in the bias of referrals to CPS, a standardized protocol for imaging is likely a step in the right direction.

The development of an institutional NAT screening protocol needs to be coupled with a concerted effort at implementation, provider education, and integration into the standard workflow to improve compliance [47]. Considering the economic impact of abuse overall, any utilization of hospital resources toward this goal is warranted. However, implementation of a standardized protocol has actually been shown to have no negative effect on hospital resource utilization, and, in fact, may actually reduce the need for hospitalization [48]. Finally, the implementation of a standard approach to the evaluation of NAT is supported by the Western Trauma Association, the Pediatric Trauma Society, and the American Pediatric Surgical Association [49, 50].

Specific Injuries

Abusive Head Trauma

The American Academy of Pediatrics broadened terminology surrounding “shaken baby syndrome” to abusive head trauma (AHT) to account for the variety of inflicted mechanisms that can lead to injury of the head, and its important structures, in children, including direct blunt force trauma, acceleration/deceleration injuries, or a combination of the two [51]. AHT accounts for one-third of all child maltreatment deaths, and infants less < 1 year of age are at the greatest risk [52]. Even without accounting for the lost quality of life and lost work, AHT costs society over $1 billion per year [7•]. The resulting disability of even mild AHT confers a lifetime burden greater even than that of a severe burn [53].

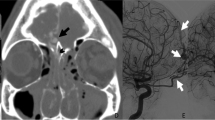

While severely injured infants may present in a delayed fashion with severe neurologic symptoms, infants with AHT can present with a non-specific constellation of findings (apnea, altered mental status, limpness, emesis, seizures, or feeding intolerance) related to a brief, resolved, unexplained event (BRUE) [54]. Both non-contrast head CT and MRI have utility in the diagnosis of AHT—the former being more useful for identifying acute injuries and skull fractures (especially with 3D reconstruction) that may require intervention and the latter elucidating subtle, parenchymal, or subacute/chronic findings [55].

Though neither is required for the diagnosis of AHT, retinal hemorrhages and subdural hematomas (SDH) are present in the majority of AHT cases [53]. Retinal hemorrhages, in cases of severe AHT, tend to be diffuse, bilateral, and multilayered, but can be unilateral and more focal depending on the mechanism of injury. Retinal hemorrhages may also be accompanied by retinoschisis (separation of the retina into multiple layers) or retinal folds/cavities. Though these findings are uncommon, controlled studies have not documented their presence in infants outside of AHT [56]. In general, SDHs are more common in AHT than in accidental head trauma. While SDHs associated with accidental injury tend to be unilateral, thin, and associated with cephalohematoma or skull fracture, SDHs associated with AHT are more likely to be larger, bilateral, and without an associated scalp or bone injury. Although SDHs associated with AHT can vary in size, location, and density, they are often multiple and are frequently found overlying the cerebral convexity, along the falx, or within the posterior fossa [57]. Imaging may also reveal other injuries including parenchymal contusions or lacerations, diffuse axonal injury, or signs of cerebral ischemia, edema, or infarct [58, 59]. Imaging should be read by an experienced neuroradiologist who is familiar with potential mimics of AHT and normal suture variants of the developing skull [60, 61].

Care for the infant with AHT centers around hemodynamic and respiratory stabilization, treatment of associated injuries, monitoring for and treatment of intracranial hypertension, and neurosurgical intervention when appropriate. Unfortunately, data is conflicting in the infant population regarding specific monitoring methods (e.g., head circumference, fontanelle examination, intracranial pressure monitors) and neurosurgical interventions (e.g., craniectomy, fontanelle tap, subdural drainage) but efforts should be made to preserve uninjured brain [62, 63]. Seizures can occur in up to two-thirds of children with AHT but can be difficult to detect in children < 2 years of age. As such, continuous EEG monitoring may be helpful early in the hospital course of injured infants [64].

It is important to remember that there has been some controversy surrounding the “classic triad” of AHT in recent years [65, 66]. However, this serves mainly as a reminder that there is no injury pattern that is pathognomonic for abuse, and providers should put injuries within the context of the reported event and make an effort to rule out underlying conditions or alternative explanations. That said, there are a variety of validated clinical prediction scores that, when used in conjunction with an individual physician’s clinical judgment, and consultation by a child abuse expert if available, may help detect the presence of AHT [67, 68] (Table 2).

Abdominal/Visceral Trauma

While inflicted abdominal trauma accounts for < 5% of NAT presentations, it is the second leading cause of death in this population [69]. Compared with accidental injury, inflicted abdominal trauma is more likely to present in a delayed fashion, more likely to affect younger children, and has a higher overall mortality. Infants and young children are also more likely to have inflicted abdominal trauma than their older counterparts [24••]. In fact, for children < 1 year of age, inflicted abdominal trauma accounts for more than 25% of admissions related to abdominal injury [70].

Initial evaluation should start with a thorough history and physical examination with any positive findings (e.g., bruising, tenderness, emesis) prompting further evaluation with intravenous contrast CT of the abdomen and pelvis. However, occult injury without overt signs of injury is not uncommon and < 12% of patients will present with abdominal bruising to suggest underlying injury [69]. Routine laboratory examination with liver enzymes (AST and ALT) and pancreatic enzymes (lipase and amylase) is an important adjunct to the initial survey [32], especially given the concern to balance the use of radiation in this young population [71]. One retrospective study used a screening cutoff of 80 IU/L for either AST or ALT which had a sensitivity of 84% for the detection of intra-abdominal injury, both of which outperformed routine evaluation with amylase/lipase [33]. The use of routine urinalysis in the screening of inflicted abdominal trauma is more controversial, but the presence of hematuria certainly warrants further evaluation [72]. The threshold for formal screening with cross-sectional imaging in potential cases of abuse should, by necessity, be lower. Detection and documentation of occult injuries in cases of abuse could be lifesaving for the abused child and siblings.

While solid organ injuries are more common in both inflicted and accidental abdominal trauma, inflicted abdominal trauma has a higher incidence of associated hollow viscous injury [24••, 69]. Treatment of inflicted abdominal trauma parallels that of accidental injury and can range from supportive to surgical depending on the injury.

Skeletal Injuries

Overall, most fractures in children are related to accidental injury and are the most common manifestation of accidental injury in children that present for medical evaluation [24••, 54]. In contrast, fractures in pre-cruising infants are much more likely to be associated with abuse, especially in the absence of a clear mechanism of injury. While older children can frequently undergo targeted radiographs based on symptoms, there should be a lower threshold for skeletal survey in children < 2 years of age with any concerns for potential maltreatment, bruising or other skin injuries, oral injuries, and unexplained intracranial injuries, and children with abused siblings [24••, 31••].

Skeletal surveys should be completed using high-resolution systems and include dedicated films (21–24 individual x-rays) of each of the body regions including each upper arm, forearm, hand, thigh, lower leg, and foot, and oblique views of the ribs [31••]. Findings can be subtle on initial survey and repeat imaging in 10–14 days is often indicated [34, 35].

While any constellation of injuries can be associated with accidental injury or abuse, the likelihood a fracture is related to abuse increases with decreasing age regardless of body region [73]. There is no specific fracture pattern that is diagnostic for NAT and even the “classic metaphyseal lesion (CML)” is controversial with evidence both supporting and refuting its association with metabolic bone disease [74,75,76]. However, certain fracture patterns (CML, posterior rib fractures, scapular fractures, spinous process fractures, sternal fractures) have a much higher specificity for abuse than other fracture patterns (e.g., clavicular fractures, long bone shaft fractures) [77]. When excluding motor vehicle collisions, rib fractures were associated with abuse in 96% of cases in children < 3 years of age [78]. Furthermore, age < 12 months, rather than anatomic location, was the only risk factor associated with increased incidence of abuse in the setting of rib fractures [79]. Similarly, long bone fractures of the humerus or femur have a high incidence (25–48%) in abused children and especially infants [73, 78, 80]. Skull fractures, on the other hand, are the most common presenting fracture and are associated with abuse in < 20% of cases, especially when simple and linear [73].

Prevention

The identification, treatment, and prevention of child abuse and neglect have been a consistent priority of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), which has culminated in the publication and continuous update of evidence-based practices for prevention [1]. This targeted effort focuses on strengthening economic support for families, changing social norms to support parents and positive parenting, providing quality care and education early in life, enhancing parenting skills to promote healthy childhood development, and intervening to lessen harms and prevent future risk [81].

Harden et al. lay out an organized framework and in-depth discussion of a variety of prevention methods specifically targeted at early childhood and infancy [82]. They divide these interventions into three broad categories—primary/universal prevention, secondary/selected prevention, and tertiary/indicated prevention. Primary prevention focuses on population-based interventions aimed at reducing maltreatment and mortality from abuse. These programs largely focus on specific demographics (e.g., young, single mothers; low-income families) to provide support in the pre- and post-natal periods. Implemented appropriately they have been shown to decrease emergency room visits, improve positive parent behaviors, and most importantly reduce infant injury and death [83, 84]. Furthermore, the economic impact of a successful primary prevention program cannot be understated. A study done in British Columbia showed that with just a $5 investment, the Period of PURPLE Crying program was estimated to save society an estimated $243 per child by educating new parents about normal infant behaviors and crying prior to discharge [85]. However, while these interventions may save hospital systems money in the long term, no program has shown a consistent reduction in the incidence of child maltreatment.

In contrast to primary prevention, secondary prevention focuses on parents with specific risk factors for abuse or who may have trouble bonding, such as parents with mental health disorders or substance use issues. Nurse Family Partnerships, which provide home visits for at risk mothers over the first several years of life, and Durham Connects, a more highly structured and intensive home visit system in North Carolina, are both examples of this type of intervention [83]. In addition, Moving Beyond Depression and Attachment and Behavioral Catch-up (ABC) are two programs which have shown promise [86, 87]. The programs have already demonstrated improved coping among parents, increased nurturing behavior, higher rates of attachment, and fewer behavior problems among older children [82].

Finally, the tertiary prevention programs are largely involuntary and are targeted at preventing recurrent maltreatment. Unfortunately, these types of programs have the lowest quality of evidence to support their effectiveness. A recent meta-analysis of 23 different randomized controlled trials found no evidence these programs reduced reports to CPS, child home removals, emergency department visits, hospitalizations, improved child development, or reduced mortality [88].

This highlights the importance of programs that aim at preventing the first incidence of maltreatment, rather than preventing recurrence.

Conclusion

Through education, use of a detailed history and exam, as well as a standardized approach, providers can help identify NAT earlier while minimizing historical biases based on race and socioeconomic status. In addition, expanded efforts regarding primary and secondary prevention appear to be most needed to help further mitigate NAT in the infant population. For the individual providers that may be called upon to evaluate children, we encourage providers to utilize standardized tools to screen patients when concerns arise, reach out to child abuse experts where available, and follow through with mandatory reporting requirements.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance •• Of major importance

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Child Abuse and Neglect Prevention. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/index.html. Accessed March 14 2021.

U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, Administration for Children and Families, Administration on Children, Youth and Families, Children’s Bureau. Child Maltreatment 2019. 2021. https://www.acf.hhs.gov/cb/research-data-technology/statistics-research/child-maltreatment. Accessed March 14 2021.

Delaplain PT, Grigorian A, Won E, Dosch AR, Schubl S, Covarrubias J, et al. Nonaccidental Trauma Is an Independent Risk Factor for Mortality Among Injured Infants. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000001901.

Estroff JM, Foglia RP, Fuchs JR. A comparison of accidental and nonaccidental trauma: it is worse than you think. J Emerg Med. 2015;48(3):274–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2014.07.030. IMPT: Retrospective review of pediatric trauma patients showing higher injury severity, 6-fold higher mortality and delayed diagnosis of NAT in 20% of cases

Litz CN, Ciesla DJ, Danielson PD, Chandler NM. A closer look at non-accidental trauma: Caregiver assault compared to non-caregiver assault. J Pediatr Surg. 2017;52(4):625–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2016.08.026.

Lee M Jr, Bachim A, Smith C, Camp EA, Donaruma-Kwoh M, Patel B. Hospital Costs and Charges of Discharge Delays in Children Hospitalized for Abuse and Neglect. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(10):572–8. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2017-0027.

Miller TR, Steinbeigle R, Lawrence BA, Peterson C, Florence C, Barr M, et al. Lifetime Cost of Abusive Head Trauma at Ages 0–4, USA. Prev Sci. 2018;19(6):695–704. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-017-0815-z. IMPT: Estimates the annual cost of abusive head trauma at $13.5 billion. The cost of existing prevention programs would be cost-effective if only 2% of cases were prevented

Jonson-Reid M, Wideman E. Trauma and Very Young Children. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2017;26(3):477–90. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2017.02.004.

Buckingham ET, Daniolos P. Longitudinal outcomes for victims of child abuse. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2013;15(2):342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-012-0342-3.

Leventhal JM, Martin KD, Gaither JR. Using US data to estimate the incidence of serious physical abuse in children. Pediatrics. 2012;129(3):458–64. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-1277.

King WK, Kiesel EL, Simon HK. Child abuse fatalities: are we missing opportunities for intervention? Pediatr Emerg Care. 2006;22(4):211–4. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pec.0000208180.94166.dd.

Jenny C, Hymel KP, Ritzen A, Reinert SE, Hay TC. Analysis of missed cases of abusive head trauma. JAMA. 1999;281(7):621–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.281.7.621.

Sheets LK, Leach ME, Koszewski IJ, Lessmeier AM, Nugent M, Simpson P. Sentinel injuries in infants evaluated for child physical abuse. Pediatrics. 2013;131(4):701–7. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-2780.

Keenan HT, Runyan DK, Marshall SW, Nocera MA, Merten DF, Sinal SH. A population-based study of inflicted traumatic brain injury in young children. JAMA. 2003;290(5):621–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.290.5.621.

Kelly P, Thompson JMD, Koh J, Ameratunga S, Jelleyman T, Percival TM, et al. Perinatal Risk and Protective Factors for Pediatric Abusive Head Trauma: A Multicenter Case-Control Study. J Pediatr. 2017;187(240–6): e4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2017.04.058.

Wu SS, Ma CX, Carter RL, Ariet M, Feaver EA, Resnick MB, et al. Risk factors for infant maltreatment: a population-based study. Child Abuse Negl. 2004;28(12):1253–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.07.005.

Rangel EL, Burd RS, Falcone RA Jr. Socioeconomic disparities in infant mortality after nonaccidental trauma: a multicenter study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2010;69(1):20–5.

Lopez ON, Hughes BD, Adhikari D, Williams K, Radhakrishnan RS, Bowen-Jallow KA. Sociodemographic determinants of non-accidental traumatic injuries in children. The American Journal of Surgery. 2018;215(6):1037–41.

Luken A, Nair R, Fix RL. On Racial Disparities in Child Abuse Reports: Exploratory Mapping the 2018 NCANDS. Child Maltreat. 2021:10775595211001926. https://doi.org/10.1177/10775595211001926. IMPT: Examines racial disparities in the United States related to child abuse and maltreatment

Falcone RA Jr, Brown RL, Garcia VF. The epidemiology of infant injuries and alarming health disparities. J Pediatr Surg. 2007;42(1):172–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2006.09.015 (discussion 6–7).

Lane WG, Rubin DM, Monteith R, Christian CW. Racial differences in the evaluation of pediatric fractures for physical abuse. JAMA. 2002;288(13):1603–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.288.13.1603.

Wood JN, Hall M, Schilling S, Keren R, Mitra N, Rubin DM. Disparities in the evaluation and diagnosis of abuse among infants with traumatic brain injury. Pediatrics 2010;126(3):408–14. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-0031.

Deans KJ, Thackeray J, Askegard-Giesmann JR, Earley E, Groner JI, Minneci PC. Mortality increases with recurrent episodes of nonaccidental trauma in children. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;75(1):161–5.

Christian CW. Committee on Child A, Neglect AAoP The evaluation of suspected child physical abuse. Pediatrics. 2015;135(5):1337–54. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-0356Very IMPT: Current recommendations from the AAP Committee on Child Abuse and Neglect for the evaluation of suspected Child Abuse.

Block RW, Krebs NF. American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Child A, Neglect, American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on N. Failure to thrive as a manifestation of child neglect. Pediatrics. 2005;116(5):1234–7. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2005-2032.

Ward MG, Ornstein A, Niec A, Murray CL. Canadian Paediatric Society C, Youth Maltreatment S. The medical assessment of bruising in suspected child maltreatment cases: A clinical perspective. Paediatr Child Health. 2013;18(8):433–42.

Harper NS, Feldman KW, Sugar NF, Anderst JD, Lindberg DM. Examining Siblings To Recognize Abuse I. Additional injuries in young infants with concern for abuse and apparently isolated bruises. J Pediatr. 2014;165(2):383-8 e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.04.004.

Sugar NF, Taylor JA, Feldman KW. Bruises in infants and toddlers: those who don’t cruise rarely bruise. Puget Sound Pediatric Research Network. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153(4):399–403. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.153.4.399.

Maguire S, Mann M. Systematic reviews of bruising in relation to child abuse-what have we learnt: an overview of review updates. Evid Based Child Health. 2013;8(2):255–63. https://doi.org/10.1002/ebch.1909.

Collier ZJ, Roughton MC, Gottlieb LJ. Negligent and Inflicted Burns in Children. Clin Plast Surg. 2017;44(3):467–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cps.2017.02.022.

Wootton-Gorges SL, Soares BP, Alazraki AL, Anupindi SA, Blount JP, Booth TN, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria(®) Suspected Physical Abuse-Child. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14(5s):S338–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacr.2017.01.036.Very IMPT: Current ACR reccomendations for imaging studies in suspected child abuse.

Lane WG, Dubowitz H, Langenberg P. Screening for occult abdominal trauma in children with suspected physical abuse. Pediatrics. 2009;124(6):1595–602. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-0904.

Lindberg DM, Shapiro RA, Blood EA, Steiner RD, Berger RP, Si Ex. Utility of hepatic transaminases in children with concern for abuse. Pediatrics. 2013;131(2):268–75. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-1952.

Harper NS, Eddleman S, Lindberg DM, Ex SI. The utility of follow-up skeletal surveys in child abuse. Pediatrics. 2013;131(3):e672–8. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2012-2608.

Zimmerman S, Makoroff K, Care M, Thomas A, Shapiro R. Utility of follow-up skeletal surveys in suspected child physical abuse evaluations. Child Abuse Negl. 2005;29(10):1075–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.08.012.

Christian CW, Levin AV. The Eye Examination in the Evaluation of Child Abuse. Pediatrics. 2018;142(2). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-1411.

Naik-Mathuria B, Akinkuotu A, Wesson D. Role of the surgeon in non-accidental trauma. Pediatr Surg Int. 2015;31(7):605–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-015-3688-x.

Cook DA, Pencille LJ, Dupras DM, Linderbaum JA, Pankratz VS, Wilkinson JM. Practice variation and practice guidelines: Attitudes of generalist and specialist physicians, nurse practitioners, and physician assistants. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(1): e0191943. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191943.

Sola R Jr, Waddell VA, Peter SDS, Aguayo P, Juang D. Non-accidental trauma: A national survey on management. Injury. 2018;49(5):921–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.injury.2018.03.006.

Thorpe EL, Zuckerbraun NS, Wolford JE, Berger RP. Missed opportunities to diagnose child physical abuse. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2014;30(11):771–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000000257.

Escobar MA Jr, Pflugeisen BM, Duralde Y, Morris CJ, Haferbecker D, Amoroso PJ, et al. Development of a systematic protocol to identify victims of non-accidental trauma. Pediatr Surg Int. 2016;32(4):377–86. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00383-016-3863-8.

Paine CW, Wood JN. Skeletal surveys in young, injured children: A systematic review. Child Abuse Negl. 2018;76:237–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.11.004.

Hymel KP, Laskey AL, Crowell KR, Wang M, Armijo-Garcia V, Frazier TN, et al. Racial and Ethnic Disparities and Bias in the Evaluation and Reporting of Abusive Head Trauma. J Pediatr. 2018;198(137–43): e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.01.048.

Stavas N, Paine C, Song L, Shults J, Wood J. Impact of Child Abuse Clinical Pathways on Skeletal Survey Performance in High-Risk Infants. Acad Pediatr. 2020;20(1):39–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2019.02.012.

Higginbotham N, Lawson KA, Gettig K, Roth J, Hopper E, Higginbotham E, et al. Utility of a child abuse screening guideline in an urban pediatric emergency department. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2014;76(3):871–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000000135.

Powers E, Tiyyagura G, Asnes AG, Leventhal JM, Moles R, Christison-Lagay E, et al. Early Involvement of the Child Protection Team in the Care of Injured Infants in a Pediatric Emergency Department. J Emerg Med. 2019;56(6):592–600. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jemermed.2019.01.030.

Riney LC, Frey TM, Fain ET, Duma EM, Bennett BL, Murtagh Kurowski E. Standardizing the Evaluation of Nonaccidental Trauma in a Large Pediatric Emergency Department. Pediatrics. 2018;141(1). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-1994.

Pflugeisen BM, Escobar MA, Haferbecker D, Duralde Y, Pohlson E. Impact on Hospital Resources of Systematic Evaluation and Management of Suspected Nonaccidental Trauma in Patients Less Than 4 Years of Age. Hosp Pediatr. 2017;7(4):219–24. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2016-0157.

Rosen NG, Escobar MA Jr, Brown CV, Moore EE, Sava JA, Peck K, et al. Child physical abuse trauma evaluation and management: A Western Trauma Association and Pediatric Trauma Society critical decisions algorithm. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2021;90(4):641–51. https://doi.org/10.1097/TA.0000000000003076.

Escobar MA Jr, Wallenstein KG, Christison-Lagay ER, Naiditch JA, Petty JK. Child abuse and the pediatric surgeon: A position statement from the Trauma Committee, the Board of Governors and the Membership of the American Pediatric Surgical Association. J Pediatr Surg. 2019;54(7):1277–85. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2019.03.009.

Christian CW, Block R. Committee on Child A, Neglect, American Academy of P. Abusive head trauma in infants and children. Pediatrics. 2009;123(5):1409–11. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2009-0408.

Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventing Abusive Head Trauma. 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/Abusive-Head-Trauma.html. Accessed March 21 2021.

Iqbal O’Meara AM, Sequeira J, Miller FN. Advances and Future Directions of Diagnosis and Management of Pediatric Abusive Head Trauma: A Review of the Literature. Front Neurol. 2020;11:118. https://doi.org/10.3389/fneur.2020.00118.

Berkowitz CD. Physical Abuse of Children. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(17):1659–66. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMcp1701446.

Vázquez E, Delgado I, Sánchez-Montañez A, Fábrega A, Cano P, Martín N. Imaging abusive head trauma: why use both computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging? Pediatr Radiol. 2014;44(Suppl 4):S589-603. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-014-3216-5.

Bhardwaj G, Chowdhury V, Jacobs MB, Moran KT, Martin FJ. Coroneo MT. A systematic review of the diagnostic accuracy of ocular signs in pediatric abusive head trauma. Ophthalmology. 2010;117(5):983-92 e17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ophtha.2009.09.040.

Orman G, Kralik SF, Meoded A, Desai N, Risen S, Huisman T. MRI Findings in Pediatric Abusive Head Trauma: A Review. J Neuroimaging. 2020;30(1):15–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/jon.12670.

Oates AJ, Sidpra J, Mankad K. Parenchymal brain injuries in abusive head trauma. Pediatr Radiol. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00247-021-04981-5.

Cartocci G, Fineschi V, Padovano M, Scopetti M, Rossi-Espagnet MC, Giannì C. Shaken Baby Syndrome: Magnetic Resonance Imaging Features in Abusive Head Trauma. Brain Sci. 2021;11(2). https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci11020179.

Mankad K, Chhabda S, Lim W, Oztekin O, Reddy N, Chong WK, et al. The neuroimaging mimics of abusive head trauma. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2019;23(1):19–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpn.2018.11.006.

Idriz S, Patel JH, Ameli Renani S, Allan R, Vlahos I. CT of Normal Developmental and Variant Anatomy of the Pediatric Skull: Distinguishing Trauma from Normality. Radiographics. 2015;35(5):1585–601. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.2015140177.

Duhaime AC, Christian CW. Abusive head trauma: evidence, obfuscation, and informed management. J Neurosurg Pediatr. 2019;24(5):481–8. https://doi.org/10.3171/2019.7.Peds18394.

Fitzpatrick S, Leach P. Neurosurgical aspects of abusive head trauma management in children: a review for the training neurosurgeon. Br J Neurosurg. 2019;33(1):47–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/02688697.2018.1529295.

Arndt DH, Lerner JT, Matsumoto JH, Madikians A, Yudovin S, Valino H, et al. Subclinical early posttraumatic seizures detected by continuous EEG monitoring in a consecutive pediatric cohort. Epilepsia. 2013;54(10):1780–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/epi.12369.

Elinder G, Eriksson A, Hallberg B, Lynøe N, Sundgren PM, Rosén M, et al. Traumatic shaking: The role of the triad in medical investigations of suspected traumatic shaking. Acta Paediatr. 2018;107 Suppl 472(Suppl Suppl 472):3–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.14473.

Debelle GD, Maguire S, Watts P, Nieto Hernandez R, Kemp AM. Abusive head trauma and the triad: a critique on behalf of RCPCH of ‘Traumatic shaking: the role of the triad in medical investigations of suspected traumatic shaking.’ Arch Dis Child. 2018;103(6):606–10. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2017-313855.

Pfeiffer H, Cowley LE, Kemp AM, Dalziel SR, Smith A, Cheek JA, et al. Validation of the PredAHT-2 prediction tool for abusive head trauma. Emerg Med J. 2020;37(3):119–26. https://doi.org/10.1136/emermed-2019-208893.

Berger RP, Fromkin J, Herman B, Pierce MC, Saladino RA, Flom L et al. Validation of the Pittsburgh Infant Brain Injury Score for Abusive Head Trauma. Pediatrics. 2016;138(1). https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-3756.

Escobar MA Jr, Flynn-OʼBrien KT, Auerbach M, Tiyyagura G, Borgman MA, Duffy SJ, et al. The association of nonaccidental trauma with historical factors, examination findings, and diagnostic testing during the initial trauma evaluation. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2017;82(6):1147–57. https://doi.org/10.1097/ta.0000000000001441.

Lane WG, Dubowitz H, Langenberg P, Dischinger P. Epidemiology of abusive abdominal trauma hospitalizations in United States children. Child Abuse Negl. 2012;36(2):142–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2011.09.010.

Miglioretti DL, Johnson E, Williams A, Greenlee RT, Weinmann S, Solberg LI, et al. The use of computed tomography in pediatrics and the associated radiation exposure and estimated cancer risk. JAMA Pediatr. 2013;167(8):700–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2013.311.

Fortin K, Wood JN. Utility of screening urinalysis to detect abdominal injuries in suspected victims of child physical abuse. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;109: 104714. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104714.

Berthold O, Frericks B, John T, Clemens V, Fegert JM, Moers AV. Abuse as a Cause of Childhood Fractures. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2018;115(46):769–75. https://doi.org/10.3238/arztebl.2018.0769.

Perez-Rossello JM, McDonald AG, Rosenberg AE, Tsai A, Kleinman PK. Absence of rickets in infants with fatal abusive head trauma and classic metaphyseal lesions. Radiology. 2015;275(3):810–21. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.15141784.

Miller M, Mirkin LD. Classical metaphyseal lesions thought to be pathognomonic of child abuse are often artifacts or indicative of metabolic bone disease. Med Hypotheses. 2018;115:65–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2018.03.017.

Ayoub DM, Hyman C, Cohen M, Miller M. A critical review of the classic metaphyseal lesion: traumatic or metabolic? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2014;202(1):185–96. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.13.10540.

Nimkin K, Kleinman PK. Imaging of Child Abuse. Radiol Clin North Am. 2001;39(4):843–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0033-8389(05)70314-6.

Mitchell IC, Norat BJ, Auerbach M, Bressler CJ, Como JJ, Escobar MA Jr, et al. Identifying Maltreatment in Infants and Young Children Presenting With Fractures: Does Age Matter? Acad Emerg Med. 2021;28(1):5–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.14122.

Paine CW, Fakeye O, Christian CW, Wood JN. Prevalence of Abuse Among Young Children With Rib Fractures: A Systematic Review. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019;35(2):96–103. https://doi.org/10.1097/pec.0000000000000911.

Wood JN, Fakeye O, Mondestin V, Rubin DM, Localio R, Feudtner C. Prevalence of abuse among young children with femur fractures: a systematic review. BMC Pediatr. 2014;14:169. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2431-14-169.

Fortson BL, Klevens J, Merrick MT, Gilbert LK, Alexander SP. Preventing child abuse and neglect: A technical package for policy, norm, and programmatic activities. Atlanta: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2016.

Harden BJ, Buhler A, Parra LJ. Maltreatment in Infancy: A Developmental Perspective on Prevention and Intervention. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2016;17(4):366–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838016658878.

Dodge KA, Goodman WB, Murphy RA, O’Donnell K, Sato J, Guptill S. Implementation and randomized controlled trial evaluation of universal postnatal nurse home visiting. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(Suppl 1):S136–43. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301361.

Olds DL, Kitzman H, Knudtson MD, Anson E, Smith JA, Cole R. Effect of home visiting by nurses on maternal and child mortality: results of a 2-decade follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(9):800–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2014.472.

Beaulieu E, Rajabali F, Zheng A, Pike I. The lifetime costs of pediatric abusive head trauma and a cost-effectiveness analysis of the Period of Purple crying program in British Columbia. Canada Child Abuse Negl. 2019;97: 104133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104133.

Ammerman RT, Putnam FW, Altaye M, Stevens J, Teeters AR, Van Ginkel JB. A clinical trial of in-home CBT for depressed mothers in home visitation. Behav Ther. 2013;44(3):359–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2013.01.002.

Bernard K, Dozier M, Bick J, Lewis-Morrarty E, Lindhiem O, Carlson E. Enhancing attachment organization among maltreated children: results of a randomized clinical trial. Child Dev. 2012;83(2):623–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01712.x.

Viswanathan M, Fraser JG, Pan H, Morgenlander M, McKeeman JL, Forman-Hoffman VL, et al. Primary Care Interventions to Prevent Child Maltreatment: Updated Evidence Report and Systematic Review for the US Preventive Services Task Force. JAMA. 2018;320(20):2129–40. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.17647.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Drs. Delaplain, Guner, Rood and Nahmias have nothing to disclose.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Intentional Violence

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Delaplain, P.T., Guner, Y.S., Rood, C.J. et al. Non-accidental Trauma in Infants: a Review of Evidence-Based Strategies for Diagnosis, Management, and Prevention. Curr Trauma Rep 8, 1–11 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40719-021-00221-1

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40719-021-00221-1