Abstract

Background

There are 14 allergens with mandatory labeling of manufactured food. A recent European regulation on the provision of food information to consumers has made it compulsory for restaurants to have a written document informing consumers on allergens contained in the dishes they serve.

Objective

To investigate restaurant staff’s knowledge about food allergies.

Methods

A standardized telephone questionnaire was administered to one member of staff at 100 restaurants in Metz and Strasbourg, France. The survey was conducted from November 2016 to March 2017.

Results

Responders included 56 owners, 4 managers, 28 waiters and 12 chefs. Seventy-four percent reported food hygiene training; 14% reported specific food allergy training. Seventy-nine percent knew about the European regulation. In all, 32% reported to be very confident in in providing a safe meal to a food-allergic customer, 30% somewhat confident, 34% confident and 4% not confident. Answers to true-false questions indicated some frequent misunderstandings: 25% believed an individual experiencing a reaction should drink water to dilute the allergen; 22% thought consuming a small amount of an allergen is safe; 39% reported allergen removal from a finished meal would render it safe; 32% agreed cooking food prevents it causing allergy and 8% were unaware allergy could cause death.

Conclusions

Despite the new regulation, currently eating out in restaurants does not put consumers with food allergies in the position of making safe food choices. Our findings also suggest the necessity for continuing to provide both food allergy and mandatory training and/or to incorporate such training into generic courses on food hygiene. Although the knowledge of the respondents was overall good in our study, certain gaps in this knowledge could be dangerous for consumers with allergies. We believe that the greater the number of trained staff in restaurants, the lower the risk of providing unsafe meals to clients.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Food allergy is a common disease affecting 4.7% of children and 3.2% of adults in Europe [1, 2]. It is also a burden for patients, with a significant impact on quality of life. Some of the foods that are considered frequent and major allergens include the following: eggs, milk eggs, milk, shrimp, wheat, peanut, fish, soy and nuts [3]. Treatment is to avoid the culprit food.

In Europe, there are 14 allergens with mandatory labeling of manufactured food. On December 2014, a European regulation on the provision of food information to consumers has made it compulsory for restaurants to provide information about the allergens contained in the dishes they serve in most European member states [4]. This provision on allergen information is not the same in each European member state. In France, it is mandatory to provide this information by a written document. This list must be made available to consumers on request.

Dining in restaurants may be dangerous for allergic consumers. Based on an internet-based survey of 51 patients with food allergies, Eigenman et al. found that 17.6% of the reported reactions occurred in restaurants [5]. Dano et al. showed that consumers had difficulties when travelling especially due to a lack of staff knowledge relative to food allergies or of seriousness regarding the severity of food allergies [6].

Currently in France, very little training on food allergies is included in generic food hygiene training which is only compulsory for a minimum of one member of the staff of a restaurant.

In the present study, we assessed the knowledge levels of restaurant personnel regarding food allergies. A structured questionnaire was administered through a telephone interview to assess the responses of the respondents.

Materials and methods

Study sample

The study was carried out by using a questionnaire in two cities—Metz and Strasbourg—located approximately 100 km apart in the Eastern region of France. Lists of restaurants were obtained from the phone book from which 159 restaurants were identified in Metz and 439 in Strasbourg. The list of restaurants was randomly selected and subsequently contacted for inclusion in the survey until 100 inclusions were obtained.

Given the distribution of restaurants between the two cities, 27% of restaurants in Metz and 73% in Strasbourg (i.e., 27 and 73 restaurants, respectively) were subjected to the survey.

Restaurants that could not be reached on two consecutive days were considered as nonrespondents and thereby excluded. Restaurants that refused to answer were also excluded.

Questionnaire

A 26-item questionnaire was designed, with the authors’ permission, from a survey conducted previously in Brighton [7]. This initial survey was piloted face-to-face with 10 food handlers, allowing ambiguities to be identified and questions refined. This survey was translated into French to which questions were added regarding knowledge of European regulations. The content of the questionnaire is described in Table 1.

Data collection

The restaurants were approached by telephone, with the intention of first interviewing the restaurants’ chefs or secondly one of the waiters given that they are on the front line in the preparation of the dishes and are key to making them safer. If this was not possible, the person answering the phone was interviewed.

The participants were informed of the aim of the study and its confidential nature, and verbal consent was given. The interviewer was a medical student in Strasbourg and a dietetic student in Metz. Both were trained by SL to have the same standard frame of discussion.

Statistical analysis

Qualitative variables were compared using Fischer’s exact test, while quantitative variables were compared using Wilcoxon or Kruskal–Wallis nonparametric tests. A total of 100 restaurants were included to ensure identification of ≥25 points differences for qualitative variable (percentages) comparisons, and at least ±10 accuracy for qualitative variable descriptions. Analyses were computed on R Software v 3.2.5 (The R Project for Statistical Computing).

Results

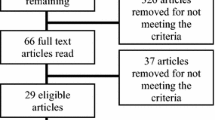

Response rate

The response rates were 35% in Strasbourg and 52% in Metz, respectively. We needed to contact 176 restaurants in Strasbourg and 56 in Metz to get the 100 inclusions.

Respondents’ awareness of food allergy

The demographic features of the respondents and previous training are summarized in Table 2. There was no statistical difference between the two cities with regard to the type of restaurant and the awareness of the European regulation. However, there were statistical differences between the two cities regarding the level of responsibility and the achievement of hygiene training.

Training

Seventy-four respondents had undergone legal food hygiene training, including 26 (96%) in Metz and 48 (66%) in Strasbourg (p < 0.001) although only 14 reported specific food allergy training— 2 (8%) in Metz and 12 (16%) in Strasbourg (p < 0.001).

Out of the 100 respondents, 4 self-evaluated themselves as uncomfortable and 96 as comfortable or better in providing a safe meal to an allergic consumer. In Metz, 26 (96%) self-evaluated themselves as very comfortable (Fig. 1). In Strasbourg, 69 (95%) self-evaluated themselves as comfortable or better.

Knowledge regarding food allergy

Eighty-seven respondents were able to name at least three of the most common allergens, respectively 18 (67%) in Metz and 69 (95%) in Strasbourg (P < 0.001).

With regard to the true–false questions, some mistakes were frequent: 22% and 39%, respectively, indicated that consuming a small amount of allergen or removing it from a cooked meal made it safe; 32% believed that cooking the food allowed the consumption of allergens; and 25% believed that drinking water could dilute the allergen. The only statistical difference between the two cities pertained to questions regarding the removal of allergens in the finished dish (p < 0.001).

The number of correct answers differed significantly according to the responsibility of the respondent: Chefs and waiters seemed to have greater knowledge of food allergies compared to owners or managers for the four aforementioned questions (p = 0.02).

In addition, when asked if allergies could be deadly, only 8% of respondents answered positively, without statistical differences between the cities or the position occupied.

A trend was also observed towards a higher percentage of respondents with all 5 correct answers to questions regarding knowledge of food allergy, along with a higher self-confidence level in preparing an allergen-free dish for an allergic consumer (p = 0.06; Fig. 2).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study conducted in France assessing the knowledge level of restaurant staff regarding food allergies in two different cities. The results showed both a lack of knowledge and training in food allergies. Moreover, we needed 232 restaurants to get the 100 answers. In most of the case, the respondent refused to answer questions about the European regulation. It could be a bias because only restaurants who consider themselves to be informed take part in the survey, and we can speculate that restaurants which have not participated, have a worse awareness and knowledge.

Most of the respondents self-assessed themselves as being comfortable or better at serving a meal to a food-allergic consumer despite disparities in their answers.

In the present study, chefs and waiters had a greater awareness of food allergies than owners and managers, which is rather reassuring since they are in direct contact with customers and would therefore be able to provide assistance. However, it would be much more reassuring if managers were more aware of food allergies and the consequences because they are the ones who can ensure that training and knowledge is an obligation and implement measures accordingly.

Our study moreover revealed differences between Metz and Strasbourg which are nevertheless located in proximity to one another. These differences could result from the characteristics of the respondents. Indeed, in Metz, most of the respondents were chefs or waiters (48 and 37%), while in Strasbourg respondents were predominantly owners (77%). These results highlight the need to conduct studies in several cities in order to accurately assess this knowledge, for all categories of staff.

Certain studies have evaluated the awareness of restaurant personnel regarding food allergies. In a study by Ahuja and Sisherer, comprised of a telephone survey of 100 restaurant staff, food allergy training was reported by 42% of the participants [8]. In the Bailey et al. study, which was used as a model for the present analysis, one third of the respondents stated having food allergy training [7]. In another study conducted in Leicester and predominantly involving Asian and Indian restaurants and using the same survey design than in the previous study, results showed that food allergy training was reported by 15% of participants [9]. In the Sogut et al. study, using face-to-face interviews, 17.1% of respondents reported food allergy training. In the present study, this rate was lower (13%), although 69% reported having had received training in the context of compulsory training in (about 30 min for a total duration of 14 h) and should be increased.

Table 3 summarizes results of true–false questions reported in the above four published studies as well as in the present study.

Statistical differences were documented between the five studies, although the percentage of erroneous responses was higher in the study of Sogut et al. However, the methodology used in this latter study differed, in addition to the fact that the rate of training in food allergy was lower than in the other studies, hence, emphasizing the importance of training in overall management.

Although previous statistics are currently inexistent, the publication and knowledge of the European regulation on the provision of food information to consumers did not appear to improve the level of staff knowledge. This is likely related to the fact that this regulation was only recently promulgated, in December 2014, and its application is not yet fully effective.

In our study, the need for training was reported by only 28% of the respondents. In the study of Bailey et al., 48% of the respondents had expressed interest in specific training. In a subsequent study, Bailey et al. had contacted all of the restaurants’ managers or owners in Brighton by proposing a cost-free food allergy training event [10]. However, the number of attendees was low, with only 11 participants from 6 different restaurants attending. This may be explained by a lack of time or interest, but also to indirect costs for restaurants due to absenteeism. In light of the latter, we believe that a specific food allergy training should be incorporated into the mandatory hygiene training.

Limitations

Our study has certain limitations. First, this is a declarative study and respondents who accepted to participate may represent those with a better knowledge or interest on food allergy. Second, the response rate was low, even if deemed adequate, for this type of study. By comparison, the response rate in the study of Bailey et al. was 56%. Finally, the results herein cannot be extrapolated to other cities, given the observed differences between the two cities in this study.

Conclusion

The legal text of Food Information Regulation is a good way forward for consumers with food allergies, but it currently does not provide what it is aimed at: giving consumers with food allergies the opportunity to make safe food choices.

To achieve improved awareness, better knowledge is necessary. This could be done by mandatory training not only on information but also on management of food allergens. EU Commission should set rules for voluntary information on unintended allergen presence (cross-contamination) as it is already envisioned in Article 36 of Food Information Regulation.

Our study furthermore underlines the necessity to conduct simultaneous multicenter studies in order to refine the accuracy of the results.

Although the knowledge of the respondents was overall good in our study, certain gaps in this knowledge could be dangerous for allergic consumers. We believe that the greater the number of trained staff in restaurants, the lower the risk of providing unsafe meals to clients.

References

Rancé F, Grandmottet X, Grandjean H. Prevalence and main characteristics of schoolchildren diagnosed with food allergies in France. Clin Exp Allergy. 2005;35(2):167–72.

Sicherer SH, Sampson HA. Food allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2010;125(2 Suppl 2):S116–S25.

EAACI. Food allergy and anaphylaxis guidelines of EAACI. 2014.

Regulation (EU) No 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on the provision of food information to consumers, amending Regulations (EC) No 1924/2006 and (EC) No 1925/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council, and repealing Commission Directive 87/250/EEC, Council Directive 90/496/EEC, Commission Directive 1999/10/EC, Directive 2000/13/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, Commission Directives 2002/67/EC and 2008/5/EC and Commission Regulation (EC) No 608/2004 Text with EEA relevance. http://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2011/1169/oj

Eigenmann PA, Zamora SA. An internet-based survey on the circumstances of food-induced reactions following the diagnosis of IgE-mediated food allergy. Allergy. 2002;57(5):449–53.

Dano D, et al. Impact of food allergies on the allergic person’s travel decision, trip organization and stay abroad. Glob J Allergy. 2015;1(2):40–3.

Bailey S, Albardiaz R, Frew AJ, Smith H. Restaurant staff’s knowledge of anaphylaxis and dietary care of people with allergies. Clin Exp Allergy. 2011;41(5):713–7.

Ahuja R, Sicherer SH. Food-allergy management from the perspective of restaurant and food establishment personnel. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2007;98(4):344–8.

Common LAR, Corrigan CJ, Smith H, Bailey S, Harris S, Holloway JA. How safe is your curry? Food allergy awareness of restaurant staff. J Allergy Ther. 2013; https://doi.org/10.4172/2155-6121.1000140. https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/368299/.

Bailey S, Billmeier Kindratt T, Smith H, Reading D. Food allergy training event for restaurant staff; a pilot evaluation. Clin Transl Allergy. 2014;4:26.

Acknowledgements

We thank Professor Smith Helen, from the Division of Public Health & Primary Care in Brighton, for her kind authorization to use her questionnaire.

We are also grateful to the restaurant staff who gave of their time to answer the survey.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

S. Lefèvre, L. Abitan, C. Goetz, M. Frey, M. Ott and F. de Blay declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

ClinicalTrial.gov Identifier: NCT03346148

Author contributions

S. Lefèvre, C. Goetz and F. de Blay designed the questionnaire and analyzed data.

L. Abitan, M. Frey and M. Ott collected data.

S. Lefèvre, C. Goetz and F. de Blay wrote the first draft. All co-authors contributed to writing the final manuscript and approved its last version.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Lefèvre, S., Abitan, L., Goetz, C. et al. Multicenter survey of restaurant staff’s knowledge of food allergy in eastern France. Allergo J Int 28, 57–62 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40629-018-0062-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40629-018-0062-2