Abstract

Purpose of Review

Healthcare workers (HCWs) may be exposed to potentially morally injurious events (PMIEs) while on the job and consequently experience acute, functional moral distress to prolonged, impairing moral injury.

Recent Findings

We reviewed 185 articles on moral distress and/or injury among HCWs. This included 91 empirical studies (approximately 50% of the retained articles), 68 editorials (37%), 18 reviews (10%), and 8 protocol papers (4%). Themes were explored using bibliometric network analysis of keyword co-citation. Empirical studies found evidence of PMIE exposure among a considerable proportion of HCWs. Greater moral distress severity was associated with worse mental and occupational health outcomes, especially among women (vs. men), younger HCWs (vs. older), nurses (vs. physicians), those who worked more hours, and HCWs with less experience. Programs to prevent and treat moral injury among HCWs lack empirical evidence.

Summary

Efforts to maintain the well-being and effectiveness of HCWs should consider the potential impact of moral injury. To that end, we introduce a dimensional contextual model of moral injury in healthcare settings and discuss recommendations for prevention and treatment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Although healthcare workers (HCWs) routinely contend with ethical issues when delivering care to patients, they also may be exposed to potentially morally injurious events (PMIEs), which include perpetrating (i.e., commission), failing to prevent (i.e., omission), or witnessing highly stressful acts that transgress one’s internalized moral beliefs [1]. For example, during the COVID-19 pandemic, HCWs sometimes restricted access to essential testing and treatment resources due to supply shortages. Low levels of PMIE exposure often result in acute, functional moral distress, [2•] defined as “the psychological distress of being in a situation in which one is constrained from acting on what one knows to be right” [3]. Repeated and/or severe PMIE exposure may result in moral injury, defined as prolonged and impairing cognitive, emotional, behavioral, social, and spiritual sequelae of PMIEs [1]. (Historically, some definitions have conceptualized being betrayed as a PMIE, though scholars disagree about whether betrayal constitutes a PMIE) [4].

Research on HCW moral distress and moral injury grew from two distinct literatures: nursing ethics and military health. Jameton coined the term moral distress in his 1984 book on nursing ethics, emphasizing instances when nurses were constrained to follow physicians’ instructions, even when they disagreed [3]. Litz’ and colleagues introduced the first conceptual model linking PMIE exposure to moral injury in 2009 [1]. During the decade that followed, studies proliferated on combat-related moral injury among military populations (see Griffin et al. for a review [5]). During the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic, interest in moral injury among HCWs surged, with nearly 200 articles attributing worsening HCW mental/occupational health problems to moral injury. Thus, we (1) report a scoping review of the literature on HCW moral distress/injury, including a bibliometric network analysis; (2) introduce a dimensional contextual model of moral injury; and (3) discuss recommendations for prevention and treatment of HCW moral distress/injury.

Method

Article identification

We searched the PubMed and PsycINFO databases on February 3, 2023, using the search terms [(moral injury OR moral distress) AND (health care work* OR health personnel)]. As is shown in the PRISMA [6] diagram (Fig. 1), our searches revealed 331 articles after removing duplicates. Once we eliminated those without peer review (n = 6), those unavailable in English (n = 1), and those unretrievable through the databases or by contacting the corresponding author (n = 5), 319 articles remained. We also set an alert to inform us of new publications that fit our search criteria between February 3 and March 31, 2023, which resulted in retaining two additional articles.

Article screening and coding

Two authors (BJG, MCW) previewed ten articles from each database, drafting codes and inclusion criteria separately. Four authors (BJG, MCW, AMJ, JMP) then met to discuss and finalize the inclusion criteria and coding scheme. Two authors (BJG, AMJ) then coded all PubMed results, and another (MCW) coded all PsycINFO results. To ensure consistency in screening and coding, all three coders convened periodically to discuss screening/coding and resolve discrepancies. As Fig. 1 shows, we eliminated 136 articles that were unrelated to moral injury among HCWs, such as those focused on military Veterans instead of HCWs or on professional burnout instead of moral injury. We retained 185 articles for analysis (see Online Supplement S1 for the references to all retained articles).

Retained articles were coded first into broad categories: (1) Editorial, (2) Review, (3) Protocol Paper, and (4) Empirical Study. Editorials included commentaries, perspective pieces, and opinion papers focused on moral distress/injury, explicitly on HCWs or a specific healthcare population. Editorials were excluded if they focused on related concepts (e.g. burnout), mentioning moral injury without exploring it conceptually. Review papers summarized the literature on moral injury in HCWs. Papers describing an intervention or proposed methods to test an intervention, without any empirical outcomes reported, were coded as protocol papers.

For empirical papers, study type was coded as quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, or case study. Quantitative studies were included if they assessed PMIE exposure, moral distress, or moral injury. Qualitative studies were retained if PMIE exposure or moral injury was directly assessed or if it emerged as a theme. Quantitative and mixed methods studies were coded as experimental (including pilot trials with random assignment to ≥ 2 conditions), longitudinal (≥ 2 assessment occasions, including 1-arm pilot trials), cross-sectional, cross-cohort (i.e., comparison of ≥ 2 cross-sectional cohorts), or psychometric in design. Articles were then coded for the occupation (e.g., nurses), setting (e.g., intensive care unit), participants’ nation or region, and contextual factors (e.g., the COVID-19 pandemic). Supplement S2 is a sortable spreadsheet of retained empirical articles and findings relevant to this review.

Bibliometric network analysis

We imported retained article citations into VOSviewer bibliometric mapping software, version 1.6.19 [7]. We mapped by keyword co-occurrence, using the full counting method. Keywords occurring in < 5 articles were dropped from the map. Synonymous keywords were collapsed as one term (e.g., SARS-COV-2 and COVID-19). Gender and sex terms were automatically combined by the software, and terms male and female were closely linked, so these terms were collapsed as gender/sex. Country, region, and nationality terms were collapsed as nation/region. Because we located no animal model studies, the keyword humans was deemed uninformative and removed. Synonyms with meaningful distinctions were kept as separate terms, namely moral injury and moral distress. Keyword connections were mapped by year. Maps were interpreted using visual inspection as well as tables in VOSviewer on node weight and link strength for prominent keywords.

Results

Results are summarized below by broad category, as we retained 91 empirical studies (approximately 50% of the retained articles), 68 editorials (37%), 18 reviews (10%), and 8 protocol papers (4%). In total, 51 keywords co-occurred across ≥ 5 retained articles (Fig. 2). Although moral distress and moral injury were amongst the most frequently occurring keywords, the two were not closely or strongly linked. The mean publication date of studies using moral distress as a keyword was earlier (2017) than that of studies using moral injury (2021). Moral distress was more closely linked to medical/bio-ethics terms, whereas moral injury was more closely linked to mental health keywords (burnout, posttraumatic stress, depression) and the COVID-19 pandemic. Supplement S3 shows the full network map and clusters, networks connected solely to moral injury, moral distress, and COVID-19.

Bibliometric analysis map of reviewed articles on healthcare workers’ moral injury. Node size (circle size and font size) indicates number of occurrences. Edge (a.k.a. line or link) weight indicates strength of association by number of co-occurrences. Shorter distance between nodes (i.e., length of edge) indicates closer relatedness of keywords. hcw, health care workers. covid-19, the coronavirus pandemic that began in 2019. psych., psychological.

Empirical studies results

Almost half (48%) of the empirical articles were quantitative, 38% were qualitative, 8% were case studies, and 5% were mixed methods (see Fig. 1). Samples were composed primarily of nurses (68 studies; 74% of the retained empirical articles), followed by physicians (55 studies; 60%), and allied health professionals (35 studies; 38%). Samples for 30 studies (coded “other” occupation) included HCWs from multiple professions in a particular setting (e.g., intensive care unit, palliative care, medical trainees). Samples represented over 20 nations, predominantly North American and European.

Quantitative and mixed methods studies were mostly cross-sectional (71%); few were longitudinal (14%) or experimental (6%). Nearly half of the quantitative and mixed-methods studies (21 studies; 43%) used the healthcare professional version of the Moral Injury Symptom Scale (MISS-HP) [8]. Adapted versions of the Moral Injury Events Scale (MIES), [9] originally validated with military service members and Veterans but modified for HCWs, were used in 18 studies (36%). Five studies used an abbreviated version of the Moral Distress Scale-Revised or the related Measure of Moral Distress for Healthcare Professionals (MDS-R/MMD-HP) [10]. Nineteen studies (38%) used items developed ad hoc to assess PMIE exposure, moral distress, or moral injury. (Intervention papers, both protocols and empirical papers, are summarized below).

Prevalence

Many studies examined the prevalence of PMIE exposure in HCWs. For instance, one assessed United States HCWs’ PMIE exposure on three occasions beginning in September 2020 [11•]. About 50% of surveyed HCWs reported witnessing others participate in actions that they perceived as a moral transgression; 20% transgressed their own moral beliefs by what they did or failed to do while providing patient care. Roughly 40% reported feeling betrayed by leaders or individuals outside their workplace, and about 30% reported feeling betrayed by their coworkers. No evidence suggested that the prevalence of PMIE exposure changed across assessment periods. Another assessed levels of moral distress severity among 3,006 physicians and nurses in mainland China, March–April 2020, using the MISS-HP [12]. About 40% of respondents endorsed symptoms severe enough to be functionally impairing.

Some evidence suggested that the risk of functionally-impairing moral injury was higher among women (versus men), younger (versus older) HCWs, nurses (versus physicians), those who worked more versus fewer hours, and providers with less experience [13]. Also, the risk of severe moral injury symptoms was lower among individuals who identified as religious/spiritual versus those who did not [14]. The impact of COVID-19 on these prevalence rates is unclear due to the paucity of prevalence estimates for HCW PMIE exposure and moral injury prior to COVID-19. Demonstrating the pandemic’s influence, rates of annual PMIE exposure in HCWs responding to the COVID-19 pandemic decreased from 56% in 2020 to 36% in 2022, when COVID-19 related hospitalizations, deaths, and shortages had declined [15]. Further, inconsistent use of measures across studies obfuscates comparisons by region, time, population, or clinical setting.

Correlates

Mental health problems were the most frequent health correlates of PMIE exposure and moral injury. One study surveyed 4,378 British HCWs, finding those with high PMIE exposure (MIES score of 17–54) were 2.6 times more likely than those with lower PMIE exposure to screen positive for common mental health disorders (depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress, or alcohol misuse) [16]. Similar findings were observed among Israeli [17] and Honduran [18] HCWs. Further, multiple studies investigated the relative contributions of different types of PMIE exposure to HCWs’ functioning; at least two found PMIEs involving one’s own actions (commissions) or failure to act (omissions) were more strongly associated with impairment than witnessing others’ wrongful actions [19, 20]. Greater PMIE exposure and moral distress severity were both associated with lower job satisfaction [21], higher rates of burnout [22], and higher turnover intentions among HCWs [23]. A few studies examined HCWs’ perceptions of organizational factors that may increase or decrease the likelihood of PMIE exposure. For instance, one study found greater perceived supervisor support was associated with lower PMIE exposure [24].

Qualitative findings

Qualitative studies most commonly described themes related to putative signs of moral injury in HCWs, clinical settings where PMIE exposure is likely, and strategies to prevent PMIE exposure or moral distress/injury. For example, Yeterian and colleagues [25] provide an overview of the psychological/behavioral, social, and spiritual/existential impacts of PMIE exposure. Others highlight specific applications of moral injury to problems experienced by HCWs [26•], including the tendency to over-work [27], to question the meaning of one’s career in healthcare [28, 29], and to feel constrained by institutional policies related to the corporatization of healthcare [30]. Focal clinical settings included end-of-life care, [31, 32] intensive and critical care units, [2•] obstetrics and neonatal care, [33, 34] geriatrics, [35] medical education/training, [36] and disaster medicine [37]. Based on views HCWs expressed, organizational changes were recommended, like shared decision-making policies, [38] decentralized leadership, [39] and forming ethics councils [34].

Results from editorials and reviews

Most editorials (56 of 68; 82%) were published 2020–2023. The COVID-19 editorials were replete with narratives of pandemic-related PMIEs and subsequent moral injury/distress. Pandemic-related commissions involved enforcing safety precautions with the potential for collateral harm (e.g., denying visitation to lower infection transmission, restricting testing or treatment due to supply shortages). Omissions included failure to prevent the infection of vulnerable individuals (e.g., immunocompromised household members). Other exposures included witnessing racial and economic disparities in care received and survival rates. Several editorials offered recommendations for expanding moral injury research on HCWs (e.g., differentiate moral injury from constructs like burnout) [40,41,42,43,44,45].

Reviews varied in their methodological rigor, so we highlight the most systematic ones. Xue and colleagues reviewed 57 articles to identify categories of PMIEs HCWs experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic [46•]. These included 1) concerns about contracting or transmitting an infection; 2) inability to work on the frontlines; 3) provision of suboptimal care; 4) care prioritization/resource allocation; 5) perceived low organizational support; and 6) issues around stigma, discrimination, and abuse. Similarly, Riedel and colleagues reviewed 19 studies on HCWs, identifying PMIEs at individual, interpersonal, and organizational levels [47•]. They described putative indicators of moral injury and risk factors associated with an increased likelihood of moral distress. Čartolovni and colleagues reviewed 7 studies with the goal of distinguishing moral distress from moral injury [48•]. Finally, Suhonen and colleagues reviewed 56 studies that focused on organizational and cultural factors that contribute to HCWs’ experiences of moral distress, such as health systems’ ethical climate (e.g., concerns about funding and priority setting, safeguarding justice and access to care) [49].

Results on interventions (protocols & empirical studies)

Most interventions designed to address HCW moral distress/injury have yet to be tested; those that have been tested did not show promising results. The only three randomized trials were for (1) an ethics training, [50] (2) an internet-based stress recovery intervention, [51, 52] and (3) an online coaching group [53]. All three reported non-significant effects on moral injury or distress measures. Untested interventions with moral injury/distress as a primary outcome were a brief, digital intervention involving psychoeducation on moral distress [54] and a brief intervention in which hospital chaplains provide emotional and spiritual support to HCWs, patients, and patients’ loved ones simultaneously [55]. Although moral injury was not the sole focus, several studies also described plans to integrate content about moral injury into interventions for general well-being of HCWs, namely Stress First Aid [56] and a coping skill-building intervention [57]. A few studies described case conceptualizations for treating moral injury, including with Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, [58] Interpersonal Psychotherapy, [59] and Cognitive Therapy [60].

Discussion

When the COVID-19 pandemic propelled the convergence of the moral distress and moral injury literatures, both challenges and opportunities emerged. Moral distress studies emphasized the intersection between organizational policies and individual HCWs’ decision-making, while moral injury studies focused on associations between PMIE exposure and individuals’ mental health. Further, in accord with the burgeoning emphasis on dimensional approaches to psychopathology, the literature documented a spectrum of outcomes from acute and functional moral distress to prolonged and impairing moral injury. Thus, an expanded model of moral injury is needed that accounts for these contextual and dimensional factors.

A dimensional contextual model of moral injury

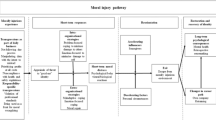

For this reason, we introduce a new model of moral injury (Fig. 3), which theorizes that the event-specific process described by Litz and colleagues [1] occurs within individual, interpersonal, organizational, and societal contexts. When a PMIE occurs, individuals have a series of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral responses, represented at the event-specific level. Cognitions affect the severity of moral distress a HCW might experience after a PMIE occurs, including appraisals about:

-

1.

Specific moral values transgressed (e.g., how do I respect my patient’s autonomy while doing no harm?)

-

2.

Personal agency (e.g., was the event intended or unanticipated?)

-

3.

Harm severity (e.g., how much suffering resulted from the event?)

-

4.

Extenuating circumstances (e.g., what mitigating factors were present during the event?)

-

5.

The possibility of repair (e.g., is the harm done amenable to reparation?)

Dimensional Contextual Model of Moral Injury. The event-specific process originally described by Litz and colleagues [1] occurs within individual, interpersonal, organizational, and societal contexts and results in a continuum of outcomes from acute and functional moral distress to prolonged and impairing moral injury.

These appraisals may evoke negative emotions, such as guilt, shame, anger, helplessness, and disgust, and constrain positive emotions, such as compassion and gratitude.

Based on the findings of this review we depart from Litz and colleagues’ model, proposing a dimensional range of responses from acute, functional moral distress to prolonged, impairing moral injury. In other words, distressing cognitions and emotions may contribute to acute, functional moral distress, such as when guilt motivates reparative action from individual amends-making to organizational policy change. Still, repair may be impeded by barriers like job-task demands (e.g., limited time to decompress in between surgical operations) and circumstantial constraints (e.g., making amends with those harmed is prohibited or impossible, due to confidentiality issues or death of a patient). Prolonged moral distress elicits functional deficits characteristic of moral injury (e.g., self-sabotaging behavior, difficulty meaning making).

At the individual level are demographic (e.g., gender, race/ethnicity), dispositional (e.g., spirituality, moral values, personality), occupational (e.g., professional ethics, autonomy in their role), and historical (e.g., trauma history) individual differences that influence event-specific responses. For example, according to Harris and colleagues, [61] personal systems of moral beliefs are often characterized by overlapping ethical principles that may conflict in a given circumstance, which in turn, increase risk of moral injury when individuals are unable to resolve conflicts between their core beliefs. HCWs may find it difficult to switch from one ethical perspective to another, resulting in a seemingly unavoidable sense of moral failure, if what is right by one standard (e.g., adherence to workplace guidelines about the efficient use of resources) is wrong by another standard (e.g., commitment to prioritizing each patient’s chance of survival). The pre-COVID-19 nursing literature highlighted how ethical dilemmas contribute to moral distress when there are conflicts between personal and professional standards, or between various professional ethical principles [62]. The COVID-19 literature then emphasized ways the pandemic increased the frequency of ethical dilemmas across professions, [48•] for example due to ventilator shortages [63]. The sequelae of moral injury also may contribute to generalized negative outcomes at the individual level, such as cumulative stress, mental health comorbidities, occupational health problems, and reduced quality of life.

Next, given that individuals’ moral beliefs are often internalized from group-based rules and norms, bonds at the interpersonal level affect and are affected by moral injury. Conflicts emerge as individuals transition between social roles with unique moral demands. For example, those who condemn themselves for perceived involvement in a PMIE expect rejection by others. Anticipating judgment, they may alienate themselves from workplace colleagues, depersonalize patients with whom they work, or create emotional distance from romantic partners, children, and friends. Studies that sampled by clinical setting (e.g., critical care or palliative care), rather than discipline, also touched on the interpersonal context of PMIEs. Pre-pandemic studies highlighted ways ethical guidelines and principles differ by discipline, such that HCWs within multidisciplinary teams may disagree about how ethical dilemmas should be handled [64]. Expanding the interpersonal context, the COVID-19 literature included ways patients’ actions and views contributed to HCW moral injury, namely through vaccine refusal [65, 66].

At the organizational and societal levels, systemic factors such as institutional betrayal, organizational support, and cultural norms impact PMIE exposure and moral distress. Institutional betrayal is a well-established risk factor for moral injury, [4] a finding replicated with healthcare workers [67,68,69]. Widespread societal events like COVID-19 place HCWs at risk of moral injury (although merely working in healthcare during a pandemic does not constitute a PMIE). For instance, specific organizational impacts of COVID-19 were (1) the implementation of policies that failed to capture the complexity of situations HCWs encountered; (2) sense of betrayal by organization leaders who were perceived as ineffective, self-serving, or uncaring; and (3) HCWs being compelled to execute decisions with which they disagree but have no power to change. Protective factors that emerged at these levels included perceived supervisor and organizational support. There may be organizational and societal consequences of moral injury too, such as workplace absenteeism, engagement, disability costs, and health inequity.

Recommendations for prevention and treatment

Our conceptual model can inform development of prevention and treatment interventions across the event-specific, individual, interpersonal, organizational, and societal levels. First, not every HCW exposed to PMIE will experience impairment. In order to allocate limited resources for treatment to make the biggest impact, there is a need to identify typical healthcare-related PMIEs and locate the clinical settings in which they most frequently occur. Clinical settings established by the current literature as common settings for PMIEs include disaster medicine, end-of-life care, intensive care, and obstetrics. Also, because dealing with ethical issues is a routine part of delivering patient care, it is essential that researchers identify how and when moral distress leads to functional deficits that characterize moral injury. To that end, screening and assessment tools are needed to better capture PMIE exposure and moral distress severity in HCWs. Screening instruments that assess different types of PMIEs, such as witnessing or participating in a PMIE, are relatively new to healthcare settings [70•]. Additionally, measures of moral distress recently became available. Whereas most of these were validated with Veterans then adapted for HCWs, [8, 71] the Moral Injury and Distress Scale was originally validated with HCWs [72].

Second, there is a need both to differentiate moral injury from related constructs and to acknowledge a wider range of correlates. Several papers acknowledged the importance of distinguishing moral injury from professional burnout in healthcare workers, akin to prior calls to differentiate moral injury and PTSD in military Veterans [73]. Unlike Veterans, who typically have been separated from military service long before moral injury interventions are delivered, there also is an opportunity for prevention with HCWs who continue working after a PMIE occurs. This provides a new opportunity to examine interacting risk and protective factors at the interpersonal and organizational levels that mitigate the association between PMIE exposure and moral distress severity (e.g., perceived supervisor support, ethical climate). The organizational and societal costs of moral injury also remain unstudied.

Finally, no treatments for moral injury have empirical support for HCWs. The few interventions that have been examined did not show promising results, though it is not clear why, in part because measures of moral distress only recently became available to evaluate the effectiveness of treatment programs. Still, several interventions are in various stages of development and testing with military Veterans, which could be adapted for use with HCWs: Adaptive Disclosure (AD), [74] Building Spiritual Strength (BSS; Harris), [75] Impact of Killing (IOK), [76] Mental Health Clinician and Chaplain Collaboration (MC3), [77] and Trauma-Informed Guilt Reduction Therapy (TrIGR) [78]. Efforts to address moral injury in HCWs could be enhanced by adapting elements of these treatments – for example, acknowledging overlapping and potentially conflicting moral imperatives, giving and receiving forgiveness, and participating in value-congruent amends-making behavior. In their current form, these treatments may have limitations to their utility in healthcare settings. They are delivered in specialty mental health clinics or community settings (e.g. interfaith centers, communities of faith) by highly trained mental health clinicians or chaplains. All require about eight 60–90 min sessions to achieve a minimally adequate dose, which limits HCWs’ access to moral injury care, given constraints on their time when providing care to patients. Access to care for HCWs could be improved by developing treatment options that are more cost-effective to scale and less impacted by geographic, temporal, and stigma-related barriers to care – for example, self-guided interventions, group therapies, and brief therapies [79]. Exemplifying potential adaptations for use with HCWs, an adaptation of BSS for HCWs, Health and Strength (HAS), is described in this issue, which included shortening the intervention from eight to six sessions [80].

Limitations and future directions

One limitation of the review was the use of broad search terms for HCWs, which may have excluded discipline-specific studies. Also, the review was not systematic because we did not check for bias in the findings of the studies reported here. There are few quantitative studies of interventions included, which limited our ability to report efficacy or effectiveness of moral injury interventions. The HCW moral injury literature disproportionately includes editorial papers; there is a need for stronger study designs and more quantitative studies of HCW moral injury predictors and outcomes. In particular, interventions should be developed and tested for those most impacted, intervening across levels from event-specific to societal (Fig. 3). Reliance on moral injury measures lacking validity for use with HCWs was a limitation of the studies included in this review, which in turn limits the conclusions drawn in our review. Systemic factors other than institutional betrayal and COVID-19 were hardly studied, e.g. health disparity, corporatization of healthcare. Cultural differences affecting and affected by moral injury remain unexamined as well, particularly among HCWs.

Conclusion

HCWs are at increased risk of moral injury due to job-related exposure to PMIEs. This is especially true during crises and disasters, where they often make critical decisions with limited time and information under circumstantial and situational constraints. We reviewed 185 articles on moral distress and moral injury in HCWs, integrating findings into a dimensional contextual model of moral injury. We also identified treatment recommendations and future research directions to enhance our understanding of moral injury in HCWs.

Data Availability

A complete list of all retained articles is available as online supplemental file S1. Codes and other details on empirical papers are available in online supplemental file S2. Further data is available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

References and Recommended Reading

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

Litz BT, Stein N, Delaney E, Lebowitz L, Nash WP, Silva C, et al. Moral injury and moral repair in war veterans: a preliminary model and intervention strategy. Clin Psychol Rev. 2009;29(8):695–706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2009.07.003.

• Kok N, Zegers M, Fuchs M, van der Hoeven H, Hoedemaekers C, van Gurp J. Development of moral injury in ICU professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic: a prospective serial interview study. Crit Care Med. 2023;51(2):231–40. https://doi.org/10.1097/CCM.0000000000005766. Conceptually distinguishes moral injury, moral distress, and burnout. Provides qualitative examples of potentially morally injurious events reported by healthcare workers.

Jameton A. Nursing Practice: The Ethical Issues. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall; 1984.

Shay J. Moral injury. Psychoanal Psychol. 2014;31(2):182–91. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036090.

Griffin BJ, Purcell N, Burkman K, Litz BT, Bryan CJ, Schmitz M, et al. Moral injury: an integrative review. J Trauma Stress. 2019;32(3):350–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22362.

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG, PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097.

van Eck NJ, Waltman L. Software survey: VOSviewer, a computer program for bibliometric mapping. Scientometrics. 2010;84:523–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-009-0146-3.

Mantri S, Lawson JM, Wang Z, Koenig HG. Identifying moral injury in healthcare professionals: the Moral Injury Symptom Scale-HP. J Relig Health. 2020;59(5):2323–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-020-01065-w.

Nash WP, Marino Carper TL, Mills MA, Au T, Goldsmith A, Litz BT. Psychometric evaluation of the moral injury events scale. Mil Med. 2013;178(6):646–52. https://doi.org/10.7205/MILMED-D-13-00017.

Epstein EG, Whitehead PB, Prompahakul C, Thacker LR, Hamric AB. Enhancing understanding of moral distress: the measure of moral distress for health care professionals. AJOB Empir Bioeth. 2019;10(2):113–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/23294515.2019.1586008.

• Amsalem D, Lazarov A, Markowitz JC, Naiman A, Smith TE, Dixon LB, et al. Psychiatric symptoms and moral injury among US healthcare workers in the COVID-19 era. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):546. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03565-9. One of the most methodologically rigorous studies of healthcare worker moral injury in terms of sample geographic diversity and longitudinal design.

Wang Z, Koenig HG, Tong Y, Wen J, Sui M, Liu H, et al. Moral injury in Chinese health professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2022;14(2):250–7. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001026.

Akhtar M, Faize FA, Malik RZ, Tabusam A. Moral injury and psychological resilience among healthcare professionals amid COVID-19 pandemic. Pak J Med Sci. 2022;38(5):1338–42. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.38.5.5122.

Mantri S, Song YK, Lawson JM, Berger EJ, Koenig HG. Moral injury and burnout in health care professionals during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2021;209(10):720–6. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000001367.

Qi M, Hu X, Liu J, Wen J, Hu X, Wang Z, et al. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the prevalence and risk factors of workplace violence among healthcare workers in China. Front Public Health. 2022;10:938423. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.938423.

Lamb D, Gnanapragasam S, Greenberg N, Bhundia R, Carr E, Hotopf M, et al. Psychosocial impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on 4378 UK healthcare workers and ancillary staff: initial baseline data from a cohort study collected during the first wave of the pandemic. Occup Environ Med. 2021;78(11):801–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/oemed-2020-107276.

Benatov J, Zerach G, Levi-Belz Y. Moral injury, depression, and anxiety symptoms among health and social care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: the moderating role of belongingness. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2022;68(5):1026–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/00207640221099421.

Rodríguez EA, Agüero-Flores M, Landa-Blanco M, Agurcia D, Santos-Midence C. Moral injury and light triad traits: anxiety and depression in health-care personnel during the coronavirus-2019 pandemic in Honduras. Hisp Health Care Int. 2021;19(4):230–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/15404153211042371.

Weber MC, Smith AJ, Jones RT, Holmes GA, Johnson AL, Patrick RNC, et al. Moral injury and psychosocial functioning in health care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Serv. 2023;20(1):19–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000718.

Borges LM, Holliday R, Barnes SM, Bahraini NH, Kinney A, Forster JE, et al. A longitudinal analysis of the role of potentially morally injurious events on COVID-19-related psychosocial functioning among healthcare providers. PLOS ONE. 2021;16(11):e0260033. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0260033.

de Veer AJE, Francke AL, Struijs A, Willems DL. Determinants of moral distress in daily nursing practice: a cross sectional correlational questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2013;50(1):100–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.08.017.

Dale LP, Cuffe SP, Sambuco N, Guastello AD, Leon KG, Nunez LV, et al. Morally distressing experiences, moral injury, and burnout in Florida healthcare providers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(23):12319. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182312319.

Stanojević S, Čartolovni A. Moral distress and moral injury and their interplay as a challenge for leadership and management: the case of Croatia. J Nurs Manag. 2022;30(7):2335–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.13835.

Hines SE, Chin KH, Glick DR, Wickwire EM. Trends in moral injury, distress, and resilience factors among healthcare workers at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(2):488. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020488.

Yeterian JD, Berke DS, Carney JR, McIntyre-Smith A, St. Cyr K, King L, et al. Defining and measuring moral injury: rationale, design, and preliminary findings from the moral injury outcome scale consortium. J Trauma Stress. 2019;32(3):363–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22380.

• Liberati E, Richards N, Willars J, Scott D, Boydell N, Parker J, et al. A qualitative study of experiences of NHS mental healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):250. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03261-8. Qualitative descriptions of healthcare worker PMIEs and moral injury symptoms.

Schommer JC, Gaither CA, Alvarez NA, Lee S, Shaughnessy AM, Arya V, et al. Pharmacy workplace wellbeing and resilience: themes identified from a hermeneutic phenomenological analysis with future recommendations. Pharmacy (Basel). 2022;10(6):e158. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10060158.

Lyu Y, Yu H, Gao F, He X, Crilly J. The lived experiences of health care professionals regarding visiting restrictions in the emergency department during the COVID-19 pandemic: a multi-perspective qualitative study. Nurs Open. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1002/nop2.1576.

Holtz HK, Weissinger GM, Swavely D, Lynn L, Yoder A, Cotton B, et al. The long tail of COVID-19: implications for the future of emergency nursing. J Emerg Nurs. 2022;S0099–1767(22):00282–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jen.2022.10.006.

Kerasidou A, Kingori P. Austerity measures and the transforming role of A&E professionals in a weakening welfare system. PLoS ONE. 2019;14(2):e0212314. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212314.

Brazil K, Kassalainen S, Ploeg J, Marshall D. Moral distress experienced by health care professionals who provide home-based palliative care. Soc Sci Med. 2010;71(9):1687–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.07.032.

Nagdee N, Manuel de Andrade V. ‘I don’t really know where I stand because I don’t know if I took something away from her’: moral injury in South African speech–language therapists and audiologists due to patient death and dying. Int J Lang Commun Disord. 2023;58(1);28–38. https://doi.org/10.1111/1460-6984.12765.

Beck CT. Secondary qualitative analysis of moral injury in obstetric and neonatal nurses. J Obstet Gynecol Neonatal Nurs. 2022;51(2):166–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jogn.2021.12.003.

Delves D. Guidelines for the formation and operation of a perinatal ethics council. Doctoral Dissertation. Fielding Graduate University. Dissertation Abstracts International Section A: Humanities and Social Sciences. 2013;73(3519305).

Brodtkorb K, Skisland AV-S, Slettebø Å, Skaar R. Ethical challenges in care for older patients who resist help. Nurs Ethics. 2015;22(6):631–41. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733014542672.

Brown MEL, Proudfoot A, Mayat NY, Finn GM. A phenomenological study of new doctors’ transition to practice, utilising participant-voiced poetry. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2021;26(4):1229–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-021-10046-x.

Marks IR, O’Neill J, Gillam L, McCarthy MC. Ethical challenges faced by healthcare workers in pediatric oncology care during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2022;70(2):e30114. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.30114.

Oerlemans AJM, van Sluisveld N, van Leeuwen ESJ, Wollersheim H, Dekkers WJM, Zegers M. Ethical problems in intensive care unit admission and discharge decisions: a qualitative study among physicians and nurses in the Netherlands. BMC Med Ethics. 2015;16(9):1–10. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-015-0001-4.

Kreh A, Brancaleoni R, Magalini SC, Chieffo DPR, Flad B, Ellebrecht N, et al. Ethical and psychosocial considerations for hospital personnel in the COVID-19 crisis: moral injury and resilience. PLOS ONE. 2021;16(4):e0249609. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0249609.

Borges LM, Barnes SM, Farnsworth JK, Bahraini NH, Brenner LA. A commentary on moral injury among health care providers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma. 2020;12(S1):S138–40. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000698.

Dean W, Talbot SG, Caplan A. Clarifying the language of clinician distress. JAMA. 2020;323(10):923–4. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2019.21576.

Lennon RP, Day PG, Marra J. Recognizing moral injury: toward legal intervention for physician burnout. Hastings Cent Rep. 2020;50(3):81. https://doi.org/10.1002/hast.1146.

Mantri S, Jooste K, Lawson J, Quaranta B, Vaughn J. Reframing the conversation around physician burnout and moral injury: ‘we’re not suffering from a yoga deficiency’. Perm J. 2021;25:ePMC8784069. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/21.005.

Maguen S, Griffin BJ. Research gaps and recommendations to guide research on assessment, prevention, and treatment of moral injury among healthcare workers. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:874729. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.874729.

Sheikhbahaei S, Garg T, Georgiades C. Physician burnout versus moral injury and the importance of distinguishing them. Radiographics. 2023;43(2):e220182. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.220182.

• Xue Y, Lopes J, Ritchie K, D’Alessandro AM, Banfield L, McCabe RE, et al. Potential circumstances associated with moral injury and moral distress in healthcare workers and public safety personnel across the globe during COVID-19: a scoping review. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:863232. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.863232. A comprehensive review on COVID-19-related PMIEs.

• Riedel P-L, Kreh A, Kulcar V, Lieber A, Juen B. A scoping review of moral stressors, moral distress and moral injury in healthcare workers during COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022;19(3):1666. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031666. Current review of empirical papers examining moral stressors, distress, and injury.

• Čartolovni A, Stolt M, Scott PA, Suhonen R. Moral injury in healthcare professionals: a scoping review and discussion. Nurs Ethics. 2021;28(5):590–602. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733020966776. Review of empirical papers, with conceptual model of healthcare worker moral injury and moral distress.

Suhonen R, Stolt M, Virtanen H, Leino-Kilpi H. Organizational ethics: a literature review. Nurs Ethics. 2011;18(3):285–303. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733011401123.

Sporrong SK, Arnetz B, Hansson MG, Westerholm P, Höglund AT. Developing ethical competence in health care organizations. Nurs Ethics. 2007;14(6):825–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733007082142.

Dumarkaite A, Truskauskaite I, Andersson G, Jovarauskaite L, Jovaisiene I, Nomeikaite A, et al. The efficacy of the internet-based stress recovery intervention FOREST for nurses amid the COVID-19 pandemic: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2022;138:104408. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.104408.

Jovarauskaite L, Murphy D, Truskauskaite-Kuneviciene I, Dumarkaite A, Andersson G, Kazlauskas E. Associations between moral injury and ICD-11 post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and complex PTSD among help-seeking nurses: a cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2022;12(5):e056289. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2021-056289.

Fainstad T, Mann A, Suresh K, Shah P, Dieujuste N, Thurmon K, et al. Effect of a novel online group-coaching program to reduce burnout in female resident physicians: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2022;5(5):e2210752. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.10752.

Nguyen B, Torres A, Sim W, Kenny D, Campbell DM, Beavers L, et al. Digital interventions to reduce distress among health care providers at the frontline: protocol for a feasibility trial. JMIR Res Protoc. 2022;11(2):e32240. https://doi.org/10.2196/32240.

Tracey E, Crowe T, Wilson J, Ponnala J, Rodriguez-Hobbs J, Teague P. An introduction to a novel intervention, ‘This is My Story’, to support interdisciplinary medical teams delivering care to non-communicative patients. J Relig Health. 2021;60(5):3282–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01379-3.

Dong L, Meredith LS, Farmer CM, Ahluwalia SC, Chen PG, Bouskill K, et al. Protecting the mental and physical well-being of frontline health care workers during COVID-19: study protocol of a cluster randomized controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2022;117:106768. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cct.2022.106768.

Weingarten K, Galván-Durán AR, D’Urso S, Garcia D. The witness to witness program: helping the helpers in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Fam Process. 2020;59(3):883–97. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12580.

Borges LM, Barnes SM, Farnsworth JK, Drescher KD, Walser RD. Case Conceptualizing in Acceptance and Commitment Therapy for Moral Injury: An Active and Ongoing Approach to Understanding and Intervening on Moral Injury. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:910414. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.910414.

D’Alessandro AM, Ritchie K, McCabe RE, Lanius RA, Heber A, Smith P, et al. Healthcare workers and COVID-19-related moral injury: an interpersonally-focused approach informed by PTSD. Front Psychiatry. 2021;12:784523. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.784523.

Murray H, Ehlers A. Cognitive therapy for moral injury in post-traumatic stress disorder. Cogn Behav Ther. 2021;14:e8. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X21000040.

Harris JI, Park CL, Currier JM, Usset TJ, Voecks CD. Moral injury and psycho-spiritual development: considering the developmental context. Spiritual Clin Pract. 2015;2(4):256–66. https://doi.org/10.1037/scp0000045.

Page P, Simpson A, Reynolds L. Bearing witness and being bounded: the experiences of nurses in adult critical care in relation to the survivorship needs of patients and families. J Clin Nurs. 2019;28(17–18):3210–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.14887.

Shortland N, McGarry P, Merizalde J. Moral medical decision-making: colliding sacred values in response to COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2020;12(S1):S128–30. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0000612.

Ponce Martinez CP, Suratt CE, Chen DT. Cases that haunt us: the rashomon effect and moral distress on the consult service. Psychosomatics J Consult Liaison Psychiatry. 2017;58(2):191–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psym.2016.09.008.

Miller EG, Mull CC. A call to restore your calling: self-care of the emergency physician in the face of life-changing stress-part 4 of 6: physician helplessness and moral injury. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2019;35(11):811–3. https://doi.org/10.1097/PEC.0000000000001972.

Ricciardelli R, MacDonald NE. Moral injury in health care: a focus on immunization. Vaccine. 2022;40(49):7011–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vaccine.2022.10.054.

French L, Hanna P, Huckle C. “If I die, they do not care”: U.K. National Health Service staff experiences of betrayal-based moral injury during COVID-19. Psychol Trauma Theory Res Pract Policy. 2022;14(3):516–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001134.

Weber MC, Smith AJ, Jones RT, Holmes GA, Johnson AL, Patrick R, et al. Moral injury and psychosocial functioning in healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Serv. 2023;20(1):19–29. https://doi.org/10.1037/ser0000718.

Zerach G, Levi-Belz Y. Moral injury and mental health outcomes among Israeli health and social care workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a latent class analysis approach. Eur J Psychotraumatol. 2021;12(1):1945749. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2021.1945749.

• Nieuwsma JA, O’Brien EC, Xu H, Smigelsky MA, Meador KG, VISN 6 MIRECC Workgroup, et al. Patterns of potential moral injury in post-9/11 combat veterans and COVID-19 healthcare workers. J Gen Intern Med. 2022;37(8):2033–40. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-022-07487-4. Compares healthcare-related and military-related moral injury.

Litz BT, Plouffe RA, Nazarov A, Murphy D, Phelps A, Coady A, et al. Defining and assessing the syndrome of moral injury: initial findings of the Moral Injury Outcome Scale Consortium. Front Psychiatry. 2022;13:923928. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.923928.

Norman SB, Griffin BJ, Pietrzak RH, McLean CP, Hamblen JL, Maguen S. The moral injury and distress scale: Psychometric evaluation and initial validation in three high-risk populations. Psychol Trauma. 2023; Advance Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/tra0001533

Norman SB, Nichter B, Maguen S, Na PJ, Schnurr PP, Pietrzak RH. Moral injury among U.S. combat veterans with and without PTSD and depression. J Psychiatr Res. 2022;154:190–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2022.07.033.

Gray MJ, Schorr Y, Nash W, Lebowitz L, Amidon A, Lansing A, et al. Adaptive disclosure: an open trial of a novel exposure-based intervention for service members with combat-related psychological stress injuries. Behav Ther. 2012;43(2):407–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2011.09.001.

Harris JI, Usset T, Voecks C, Thuras P, Currier J, Erbes C. Spiritually integrated care for PTSD: A randomized controlled trial of ‘Building Spiritual Strength.’ Psychiatry Res. 2018;267:420–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.06.045.

Maguen S, Burkman K, Madden E, Dinh J, Bosch J, Keyser J, et al. Impact of killing in war: a randomized, controlled pilot trial: impact of killing in war. J Clin Psychol. 2017;73(9):997–1012. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22471.

Pyne JM, Sullivan S, Abraham TH, Rabalais A, Jaques M, Griffin B. Mental health clinician community clergy collaboration to address moral injury symptoms: a feasibility study. J Relig Health. 2021;60(5):3034–51. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-021-01257-y.

Norman S. Trauma-Informed Guilt Reduction Therapy: overview of the treatment and research. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry. 2022;9(3):115–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-022-00261-7.

Resnick KS, Fins JJ. Professionalism and Resilience After COVID-19. Acad Psychiatry. 2021;45(5):552–6. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40596-021-01416-z.

Chamberlin ES, Usset TJ, Fantus S, Kondrath SR, Butler M, Weber MC, Wilson MA. Moral injury in healthcare: Adapting the Building Spiritual Strength (BSS) intervention to Health and Strength (HAS) for civilian and military healthcare workers. Curr Treat Options Psychiatry. this issue.

Acknowledgements

This research is supported by the Center for Mental Health Outcomes Research and by the Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Academic Affiliations Advanced Fellowship Program in Mental Illness Research and Treatment. The expressed opinions are those of the authors and not necessarily the official positions of the United States Government or academic affiliates.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Griffin, B.J., Weber, M.C., Hinkson, K.D. et al. Toward a Dimensional Contextual Model of Moral Injury: A Scoping Review on Healthcare Workers. Curr Treat Options Psych 10, 199–216 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-023-00296-4

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40501-023-00296-4