Abstract

We review recent advances in the application of behavioral economics to alcohol use disorders (AUDs). Specifically, we review individual differences in alcohol demand (i.e., the relative reinforcing value of alcohol) and delayed reward discounting (i.e., impulsive decision-making) in relation to AUDs. Additionally, we review the efficacy of reinforcement-based clinical applications. What emerges from the literature is an extensive body of cross-sectional research implicating alcohol demand and delayed reward discounting with alcohol misuse. However, more research is needed to examine these domains across the lifespan in order to understand their longitudinal trajectories. Similarly, clinical research is consistently supportive of reinforcement-based clinical interventions, but the number of randomized controlled trials to date is relatively small and there has been limited examination of the putative mechanisms of behavior change.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Behavior economics integrates concepts from psychology and microeconomics to understand the transactions that individuals make with the world [1•]. In the case of alcohol use disorders (AUDs) and other forms of addiction, a behavioral economic approach is an extension of an operant learning perspective, in which alcohol and other drugs fundamentally represent powerful positive and negative reinforcers that come to dominate an individual’s behavioral repertoire [2, 3]. This is combined with the insight that complex reinforcement environments, where diverse alternatives and schedules are available, are effectively microeconomies, in which the person (or animal) makes cost-benefit decisions about how financial or behavioral resources are allocated [1•, 4, 5].

Although its provenance is different from other forms of behavioral economics that draw on cognitive psychology [6] or game theory [7], this approach has a similarly high emphasis on decision-making as a critical determinant of the behavior of an individual, healthy or unhealthy. More specifically, behavioral economics conceptualizes addictive disorders as disorders of reoccurring maladaptive decision-making based on two types of preferences. The first form of disordered preferences is that the problem substance is excessively highly valued as a reinforcer, and the second form is an excessive preference for smaller immediate rewards compared to larger delayed rewards. In this review, we will concisely review the application of behavioral economics to understanding the etiology and treatment of AUDs. The general topics include alcohol demand (i.e., factor 1: the relative reinforcing value of alcohol), delayed reward discounting (DRD; i.e., factor 2: impulsive decision-making), and clinical applications. In each section, we will review the state of the contemporary literature and identify gaps in knowledge that are priorities for future work.

Alcohol Demand

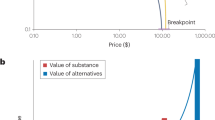

Demand is a fundamental concept in economics, referring to how much is sought or consumed at a given price. In a behavioral economic context, alcohol demand refers to how much alcohol is sought or consumed under conditions of prices that take various forms, including money or behavioral responses [8, 9]. In this context, demand putatively reflects how valuable alcohol is to the individual as a reinforcer. Historically, demand was typically measured using operant self-administration paradigms which defined costs as behavioral responses for alcohol or other drugs (e.g., plunger pulls) [10–12]. More recently, studies in humans now often assess the level of demand for alcohol with a purchase task in which subjects are asked to estimate alcohol consumption at varying levels of price per drink [13, 14]. Specifically, examination of an individual’s level of consumption across escalating prices can be used to generate five conceptually related indices of demand [15, 16] (Table 1) and an overall demand curve which summarizes the relationship (Fig. 1). The primary study methodologies for measuring alcohol demand are (1) trait-based demand (i.e., typical demand), (2) state-based demand (i.e., demand in varying conditions), and (3) behavioral theories of choice (i.e., alcohol demand versus other commodities).

Two prototypic demand curves illustrating the individual indices of demand and higher and lower levels in two hypothetical individuals. Intensity refers to consumption at zero cost, breakpoint refers to the price that entirely suppresses consumption to zero, and elasticity refers to the slope of the demand curve, reflecting sensitivity to escalating costs. O max refers to maximum expenditure across the demand curve (not shown)

Trait-Based Demand

Trait-based alcohol demand (i.e., estimated typical level of consumption at varying levels of price) has been consistently associated with greater weekly alcohol consumption [13, 15, 17, 18], including frequency of heavy drinking [13], caffeinated alcoholic beverage consumption [19], alcohol-related problems [13, 16, 18, 20], and less of a decrease in drinking following a harm reduction intervention [8]. Notably, a recent study found that in heavy-drinking college students, symptoms of depression and posttraumatic stress disorder were uniquely associated with elevated alcohol demand even after taking into account differences in typical drinking levels [21]. This suggests that the negative reinforcing properties of alcohol may be particularly salient for those experiencing aversive psychological symptoms. Another interesting recent study of college drinkers identified alcohol demand to be higher in smokers even after controlling for alcohol consumption, gender, alcohol problems, and depressive symptoms [22]. These latest studies suggest that alcohol demand uniquely contributes to the relationship between elevated alcohol use and co-occurring processes such as negative affective symptoms and cigarette smoking. Although these studies all utilized hypothetical rather than actual rewards, a methodological study determined that there was a close correspondence between value preferences for hypothetical and actual alcohol, and between estimated consumption and actual consumption, supporting the validity of using estimated consumption [23]. Furthermore, the hypothetical alcohol purchase task has been shown to demonstrate good to excellent 2-week test-retest reliability [16]. Although only one study has been conducted to date, the temporal stability of a cigarette purchase task has been found to be similarly high [24] and, more broadly, the relationships between individual differences in tobacco demand and nicotine dependence [e.g., [25, 26]] have been very similar to the preceding findings, suggesting the generality of these relationships.

State-Based Demand

The preceding studies all used an alcohol purchase task that focused on alcohol demand in a trait-like way (i.e., how much an individual estimated they would consume on a typical drinking occasion). However, several studies have applied purchase tasks and related measures to improve the assessment of acute motivation for alcohol, most commonly assessed via subjective craving. For example, state alcohol demand has been shown to dynamically increase in an alcohol cue reactivity paradigm [17, 27]. Similarly, two recent studies found that negative affect and stress inductions significantly increased alcohol demand [28, 29]. These findings are similar to recent studies applying behavioral economics to understand acute motivation for tobacco [30–32]. These findings suggest that state-based alcohol demand may complement existing measures of acute motivation, such as craving, affect, or arousal.

Behavioral Theories of Choice

The preceding approaches all characterize the reinforcing value of alcohol by scaling it against a domain-general (nonspecific) unit of cost (i.e., money, effort). In contrast, other methods can be used to assess the proportionate value of a commodity in relation to, and even in combination with, multiple other available reinforcers. This approach, referred to as behavioral theories of choice [33, 34], captures the extent to which the overall proportion of reinforcement is dependent on alcohol. For example, a person with a low ratio of proportionate alcohol-related reinforcement exhibits a profile that suggests drinking is a reinforcing activity that is generally independent of other forms of reinforcement, whereas a person with a high ratio of proportionate alcohol-related reinforcement suggests that alcohol operates synergistically, as a complement, to many reinforcing activities in a person’s life. In young adults, there is evidence that heavy drinkers report less reinforcement from nondrug activities compared to matched controls [35, 36]. Moreover, alcohol-free reinforcement (i.e., enjoyability of alcohol-free activities) is significantly negatively associated with alcohol misuse and vice versa [8, 36–38]. Furthermore, proportionate alcohol-related reinforcement (i.e., ratio of alcohol-related to alcohol-free activity participation and enjoyment) has been found to predict treatment response [38], and a recent study found that a behavior economic intervention designed to increase alcohol-free reinforcement significantly reduced drinking [39], particularly for individuals with low baseline levels of alternative reinforcement.

Summary

The overall body of work in this area suggests two robust conclusions. First, human laboratory and purchase task studies provide strong support for an operant perspective on alcohol motivation, suggesting that consumption is substantially influenced by response cost contingencies. Second, individual differences in alcohol demand are significantly associated with the level of alcohol consumption, severity of alcohol problems, and other clinically relevant variables. What is less clear at this point, however, is the etiological relevance of high alcohol demand. That is, does alcohol demand recursively predict the escalation of alcohol misuse or is it another indicator of misuse, a symptom. Theoretically, it is the former, but longitudinal studies are necessary to test that hypothesis and none have been published to date. Furthermore, longitudinal studies are needed to tease out the mediating and moderating relationships among these behavioral economic variables and other conventional measures of risk, such as drinking motives or alcohol expectancies [40, 41]. Finally, much of the research studies to date have been conducted on college students, and therefore replicating and extending these results to adult community populations and noncollege young adults is of high priority moving forward.

Delayed Reward Discounting

Delayed reward discounting refers to an individual’s propensity to select smaller immediate rewards over larger delayed rewards. This is typically assessed using intertemporal choice tasks comprised of dichotomous choices between smaller-immediate and larger-delayed rewards (most commonly, differing monetary amounts). Thus, a prototypic DRD task item, such as $75 today versus $100 in 1 week, assesses the extent to which a person is willing to give up a larger reward to receive a smaller one immediately. Individuals are asked a series of questions with varying reward amounts and reward delays, from which an index is derived reflecting their overall capacity to delay gratification (for indices of DRD preference, see Table 1) [42, 43]. Although most studies on DRD use hypothetical reward tasks, several studies have found close correspondence between DRD assessments for actual and hypothetical rewards in both healthy [44–46] and addiction samples [47].

A substantial body of research has examined differences in DRD between individuals with AUDs and healthy comparisons, consistently finding that those with AUDs exhibit significantly greater impulsive DRD compared to healthy subjects [48–51]. Notably, DRD is associated with AUD severity as well as drinking quantity and frequency [20, 52–54, 55•]. A recent meta-analysis synthesized the findings of numerous categorical studies (including 17 on alcohol), finding highly significant, medium magnitude effect size differences between groups exhibiting addictive behavior and controls (Cohen’s d = .50 in clinical alcohol samples; d = .26 in subclinical alcohol samples) [56•].

The cross-sectional nature of the bulk of the studies on impulsive DRD does not allow for determination of whether impulsive DRD is a risk factor for addictive behavior or if it is merely a consequence of prolonged substance use [57, 58]. However, a handful of research studies support that DRD preference at least partially predates the development of addiction. For example, more impulsive DRD in adolescence has been shown to predict earlier onset of AUD symptoms in retrospective studies [59, 60] and most recently, has been shown to prospectively predict severity of alcohol misuse over a 6-month period [61]. In a longitudinal study of adolescents, impulsive DRD was shown to mediate the relationship between reduced working memory capacity and increased drinking frequency over time [62].

Additionally, support for the role of DRD in AUD prognosis has been demonstrated in a series of naturalistic studies using an index of DRD that characterizes a person’s relative allocation of discretionary monetary expenditures to alcoholic beverages (immediate reward) versus savings (delayed rewards). In the first study, Tucker et al. (2002) found that this measure of DRD predicts naturalistic resolution among untreated problem drinkers [63]. In a larger follow-up study, Tucker, Vuchinich, Black, and Rippens (2006) found that this discretionary spending pattern index added incremental utility to established predictors in determining drinking outcomes at a 2-year follow-up [64]. This was further replicated in a study using an interactive voice response telephone system as a form of ecological momentary assessment, again with less expenditures on alcohol and more on savings incrementally predicting natural resolution and moderation outcomes [65, 66].

With regard to research priorities, although longitudinal research has been conducted, considerably more is necessary to determine whether impulsive DRD reliably predicts the onset of alcohol and other substance misuse and, if so, how DRD as a risk factor relates to other risk factors, behavioral economic and otherwise. Similarly, relatively little work has contextualized DRD over the life course, and, given that chronic and early life stress are associated with addictive behavior [67], DRD could be examined as a potential mechanism of these relationships [68]. One challenge to incorporating DRD into a range of research and clinical contexts is that the assessment can be relatively time intensive to administer. As such the development of brief but accurate methods for assessing DRD will increase its versatility. Two recent notable studies have utilized unique methods to isolate eight and five dichotomous choices, respectively [69, 70], offering abbreviated fast methods for assessing DRD. Future studies will need to validate these novel measures in substance abuse samples in particular.

Finally, one of the most salient open questions is whether DRD is an endophenotype for AUDs. Indeed, evidence supports its association with AUDs and its heritability [71–74, 75•]. In addition, a small number of studies have linked impulsive DRD to dopamine-related polymorphisms [76–80], although the findings are already somewhat inconsistent. Much work is needed to characterize genetic influences on DRD and, ultimately, whether DRD mediates the relationship between particular genes and risk for AUDs.

Clinical Applications

Clinical applications of behavioral economics have typically focused on altering the reinforcement contingencies in an individual’s life to increase the value of sobriety and the costs of drinking. The longest standing reinforcement-based treatment is the community reinforcement approach (CRA) [81], which attempts to restructure the environmental contingencies in a patient’s life so that abstinence becomes more reinforcing than drinking. A typical consequence in individuals with AUDs is that their drinking has reduced the number of reinforcing opportunities other than alcohol in their life. Therefore, CRA attempts to restore healthy alternative forms of reinforcement that are mutually exclusive with drinking for the individual. Regarding the efficacy of CRA, early trials reported very positive outcomes [81–83] and subsequently positive outcomes have been found in several populations, including challenging groups, such as homeless adults [84] and young adults [85]. Based on this, systematic reviews have found the CRA to have robust support for the treatment of AUDs [86, 87] and fairly consistent support for treating other substance use disorders (for a systematic review, see [88•]). In addition, the CRA approach has also been adapted for use with family members, termed Community Reinforcement Approach Family Training (CRAFT). Many individuals with AUDs are not actively motivated to change their drinking and the CRAFT model provides training to family members to encourage the individual to seek treatment. Specifically, the CRAFT program offers strategies for changing the home environmental contingencies to positively reinforce not drinking, to not reinforce drinking, and to positively encourage the individual to seek treatment. Clinical studies to date have supported the CRAFT approach for both alcohol [89–91] and other drugs [88•]. Considered together, existing clinical research is consistently supportive of CRA and CRAFT, but the number of randomized controlled trials to date is relatively small.

The second major form of reinforcement-based treatment is contingency management (CM). Unlike CRA, which focuses on larger contingencies in a person’s life, CM seeks to reinforce pro-treatment outcomes directly using incentives [92]. Although only two studies to date have examined the efficacy of CM in AUDs, both found that CM was associated with significantly more positive outcomes and the more recent study found that CM can be implemented successfully by trained community providers [93•, 94]. Furthermore, a meta-analysis of CM for substance use disorders has found it to be consistently efficacious across a number of substances [95]. Importantly, new alcohol biomarkers and technologies are circumventing the problem of depending upon breath alcohol content (BrAC). For example, ethyl glucuronide (EtG) is a biomarker of recent alcohol use that has a longer half-life and can be detected in urine for up to 2 days. A recent study found that EtG plus BrAC compliance tests substantially increased abstinence in a CM feasibility study [96]. Similarly, another study incorporated a secure continuous remote alcohol monitoring (SCRAM) bracelet into a CM feasibility trial [97]. The SCRAM device is a transdermal alcohol monitor that is used primarily in legal settings for monitoring alcohol use in adjudicated individuals. It provides around-the-clock monitoring and permitted verification of contingencies during a 2-week CM trial period, which significantly decreased drinking during this period [97]. This device has been shown to correlate very closely with breath alcohol content (.84) [98] and yields good sensitivity at blood alcohol concentration (BAC) ≥.08 g/dl (88 %) without false positives [99]. However, limitations still remain including accurate detection of lower BAC (<.08 g/dl), water accumulation, and signal interference [99].

There are a number of research priorities for clinical applications of behavioral economics, both in extending existing findings and taking qualitatively new steps forward. As noted above, the total number of RCTs for these interventions for AUDs remains relatively small. In addition, with regard to CRA and CM interventions, relatively little work has been done to characterize whether the positive intervention effects are actually mediated by the putative mechanisms of action (e.g., increases in alcohol-free reinforcement). For example, it would be particularly interesting to see the extent to which a change in the relative reinforcing value of alcohol mediates the relationship between CRA and CM treatment and positive drinking outcomes. Equally, no studies (to our knowledge) have examined behavioral economic variables as moderators of CRA or CM interventions. Level of alcohol demand, for example, is an obvious candidate for moderating responsiveness to CM. Related to this, behavioral economic variables may be useful for characterizing alcohol pharmacotherapy mechanisms, as one study has already demonstrated in the case of naltrexone [100]. In general, relatively little work has been conducted examining the mechanisms of behavior change that underlie these treatment strategies. Expanding the contexts for delivering these treatments is also a high priority, and there is promising evidence that CRA and CM can be provided in computer-based formats. Specifically, a recent trial investigated the addition of a computer-delivered intervention comprising both components and found that the package significantly improved retention and abstinence [101]. Because the two components were combined, however, it was unclear whether differential roles were present and what the underlying mechanisms were.

As a final point, beyond existing interventions, behavioral economics may also contribute to novel treatments. For example, a recent randomized controlled trial combining a brief motivational intervention (BMI) and a behavioral economic supplement for heavy-drinking young adults found that the supplement significantly improved outcomes compared to the BMI alone [39]. The additional module was focused on increasing the salience of academic contingencies (e.g., the relationship between academic performance and future career prospects), increasing involvement in nondrinking activities, and examining the discrepancy between drinking behavior and the individual’s goals. This was the case for both short- and long-term outcomes. Furthermore, a recent study found that working memory training substantially decreased DRD in stimulant addicts [102], suggesting that this approach may have clinical utility. Additionally, other studies have used methods of altering temporal attention to significantly reduce DRD in healthy [103] and obese adults [104]. Thus, in the future, impulsive DRD may also be a treatment target in problematic drinkers.

Conclusion

The goal of this review was to provide a concise overview of the research program applying behavioral economics to understanding AUDs and to draw attention to priorities for further research. What emerges from the literature is an extensive body of research implicating high levels of alcohol demand and highly impulsive DRD with AUDs, but the nature of these relationships is not definitive at this point. Consistent with the behavioral tradition that these perspectives and methods emerged from, the picture is most clear in laboratory studies and descriptive psychopathology studies, when, for example, individuals with AUDs are contrasted with control participants. Despite the strong descriptive account of alcohol demand and DRD in AUDs, there are relatively few studies considering these variables across the lifespan, from genetic influences that contribute to innate differences to environmental and developmental influences. Situating these behavioral economic variables in the larger etiological framework of alcohol use disorders may well be the highest broad priority going forward.

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

Bickel WK, Johnson MW, Koffarnus MN, MacKillop J, Murphy JG. The behavioral economics of substance use disorders: reinforcement pathologies and their repair. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2014;10:641–77. Review of the behavioral economics of substance use disorders that provides a view of substance use disorders as reinforcer pathologies.

Bigelow G. An operant behavioral perspective on alcohol abuse and dependence. In: Heather N, Peters TJ, Stockwell T, editors. International handbook of alcohol dependence and problems. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons; 2001. p. 299–315.

Higgins ST, Heil SH, Lussier JP. Clinical implications of reinforcement as a determinant of substance use disorders. Annu Rev Psychol. 2004;55:431–61.

Hursh SR. Economic concepts for the analysis of behavior. J Exp Anal Behav. 1980;34:219–38.

Hursh SR. Behavioral economics. J Exp Anal Behav. 1984;42:435–52.

Kahneman D. A perspective on judgment and choice: mapping bounded rationality. Am Psychol. 2003;58:697–720.

Camerer C. Behavioral game theory: experiments in strategic interaction. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 2003.

MacKillop J, Murphy JG. A behavioral economic measure of demand for alcohol predicts brief intervention outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2007;89:227–33.

Spanagel R, Holter S. Long-term alcohol self-administration with repeated alcohol deprivation phases: an animal model of alcoholism? Alcohol Alcohol. 1999;34:231–43.

Shahan TA, Bickel WK, Madden GJ, Badger GJ. Comparing the reinforcing efficacy of nicotine containing and de-nicotinized cigarettes: a behavioral economic analysis. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 1999;147:210–6.

Mello NK, Mendelson JH. Operant analysis of drinking patterns of chronic alcoholics. Nature. 1965;206:43–6.

Sanders RM, Nathan PE, O’Brien JS. The performance of adult alcoholics working for alcohol: a detailed operant analysis. Br J Addict Alcohol Drugs. 1976;71:307–19.

Murphy JG, MacKillop J. Relative reinforcing efficacy of alcohol among college student drinkers. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2006;14:219–27.

Gray JC, MacKillop J. Interrelationships among individual differences in alcohol demand, impulsivity, and alcohol misuse. Psychol Addict Behav. 2014;28:282–7.

MacKillop J, Murphy JG, Tidey JW, Kahler CW, Ray LA, Bickel WK. Latent structure of facets of alcohol reinforcement from a behavioral economic demand curve. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2009;203:33–40.

Murphy JG, MacKillop J, Skidmore JR, Pederson AA. Reliability and validity of a demand curve measure of alcohol reinforcement. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2009;17:396–404.

MacKillop J, O’Hagen S, Lisman SA, Murphy JG, Ray LA, Tidey JW, et al. Behavioral economic analysis of cue-elicited craving for alcohol. Addiction. 2010;105:1599–607.

Acker J, Amlung M, Stojek M, Murphy JG, Mackillop J. Individual variation in behavioral economic indices of the relative value of alcohol: incremental validity in relation to impulsivity, craving, and intellectual functioning. J Exp Psychopathol. 2012;3:423–36.

Amlung M, Few LR, Howland J, Rohsenow DJ, Metrik J, MacKillop J. Impulsivity and alcohol demand in relation to combined alcohol and caffeine use. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2013;21:467–74.

MacKillop J, Miranda Jr R, Monti PM, Ray LA, Murphy JG, Rohsenow DJ, et al. Alcohol demand, delayed reward discounting, and craving in relation to drinking and alcohol use disorders. J Abnorm Psychol. 2010;119:106–14.

Murphy JG, Yurasek AM, Dennhardt AA, Skidmore JR, McDevitt-Murphy ME, MacKillop J, et al. Symptoms of depression and PTSD are associated with elevated alcohol demand. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;127:129–36.

Yurasek AM, Murphy JG, Clawson AH, Dennhardt AA, MacKillop J. Smokers report greater demand for alcohol on a behavioral economic purchase task. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2013;74:626.

Amlung M, Acker J, Stojek MK, Murphy JG, MacKillop J. Is talk “cheap”? An initial investigation of the equivalence of alcohol purchase task performance for hypothetical and actual rewards. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36:716–24.

Few LR, Acker J, Murphy C, MacKillop J. Temporal stability of a cigarette purchase task. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14:761–5.

MacKillop J, Murphy JG, Ray LA, Eisenberg DTA, Lisman SA, Lum JK, et al. Further validation of a cigarette purchase task for assessing the relative reinforcing efficacy of nicotine in college smokers. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;16:57–65.

Murphy JG, MacKillop J, Tidey JW, Brazil LA, Colby SM. Validity of a demand curve measure of nicotine reinforcement with adolescent smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;113:207–14.

Amlung M, MacKillop J. Understanding the effects of stress and alcohol cues on motivation for alcohol via behavioral economics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38:1780–9.

Amlung M, MacKillop J. Clarifying the relationship between impulsive delay discounting and nicotine dependence. Psychol Addict Behav. 2014;28(3):761–8.

Rousseau GS, Irons JG, Correia CJ. The reinforcing value of alcohol in a drinking to cope paradigm. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;118:1–4.

MacKillop J, Brown CL, Stojek MK, Murphy CM, Sweet L, Niaura RS. Behavioral economic analysis of withdrawal- and cue-elicited craving for tobacco: an initial investigation. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14:1426–34.

Acker J, MacKillop J. Behavioral economic analysis of cue-elicited craving for tobacco: a virtual reality study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2013;15:1409–16.

Hitsman B, MacKillop J, Lingford-Hughes A, Williams TM, Ahmad F, Adams S, et al. Effects of acute tyrosine/phenylalanine depletion on the selective processing of smoking-related cues and the relative value of cigarettes in smokers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2008;196:611–21.

Vuchinich RE, Tucker JA. Behavioral theories of choice as a framework for studying drinking behavior. J Abnorm Psychol. 1983;92:408–16.

Vuchinich RE, Tucker JA. Contributions from behavioral theories of choice to an analysis of alcohol abuse. J Abnorm Psychol. 1988;97:181–95.

Correia CJ, Carey KB, Simons J, Borsari BE. Relationships between binge drinking and substance-free reinforcement in a sample of college students: a preliminary investigation. Addict Behav. 2003;28:361–8.

Correia CJ, Simons J, Carey KB, Borsari BE. Predicting drug use: application of behavioral theories of choice. Addict Behav. 1998;23:705–9.

Correia CJ, Carey KB, Borsari B. Measuring substance-free and substance-related reinforcement in the natural environment. Psychol Addict Behav. 2002;16:28–34.

Murphy JG, Correia CJ, Colby SM, Vuchinich RE. Using behavioral theories of choice to predict drinking outcomes following a brief intervention. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2005;13:93–101.

Murphy JG, Dennhardt AA, Skidmore JR, Borsari B, Barnett NP, Colby SM, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a behavioral economic supplement to brief motivational interventions for college drinking. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80:876–86.

Carey KB, Correia CJ. Drinking motives predict alcohol-related problems in college students. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 1997;58:100.

Patrick ME, Wray-Lake L, Finlay AK, Maggs JL. The long arm of expectancies: adolescent alcohol expectancies predict adult alcohol use. Alcohol Alcohol. 2010;45:17–24.

Mazur JE. An adjusting procedure for studying delayed reinforcement. In: Commons ML, Mazur JE, Nevin JA, Rachlin H, editors. The effect of delay and of intervening events on reinforcement: quantitative analyses of behavior, vol. 5. NJ: Hillsdale; 1987. p. 55–73.

Myerson J, Green L, Warusawitharana M. Area under the curve as a measure of discounting. J Exp Anal Behav. 2001;76:235–43.

Johnson MW, Bickel WK. Within-subject comparison of real and hypothetical money rewards in delay discounting. J Exp Anal Behav. 2002;77:129–46.

Bickel WK, Pitcock JA, Yi R, Angtuaco EJ. Congruence of BOLD response across intertemporal choice conditions: fictive and real money gains and losses. J Neurosci. 2009;29:8839–46.

Madden GJ, Begotka AM, Raiff BR, Kastern LL. Delay discounting of real and hypothetical rewards. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2003;11:139–45.

Lawyer SR, Schoepflin F, Green R, Jenks C. Discounting of hypothetical and potentially real outcomes in nicotine-dependent and nondependent samples. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;19:263–74.

Bjork JM, Hommer DW, Grant SJ, Danube C. Impulsivity in abstinent alcohol-dependent patients: relation to control subjects and type 1-/type 2-like traits. Alcohol. 2004;34:133–50.

Petry NM. Delay discounting of money and alcohol in actively using alcoholics, currently abstinent alcoholics, and controls. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2001;154:243–50.

Kirby KN, Petry NM. Heroin and cocaine abusers have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than alcoholics or non-drug-using controls. Addiction. 2004;99:461–71.

Mitchell JM, Fields HL, D’Esposito M, Boettiger CA. Impulsive responding in alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29:2158–69.

Amlung M, Mackillop J. Delayed reward discounting and alcohol misuse: the roles of response consistency and reward magnitude. J Exp Psychopathol. 2011;2:418–31.

Christiansen P, Cole JC, Goudie AJ, Field M. Components of behavioural impulsivity and automatic cue approach predict unique variance in hazardous drinking. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2012;219:501–10.

Field M, Christiansen P, Cole J, Goudie A. Delay discounting and the alcohol Stroop in heavy drinking adolescents. Addiction. 2007;102:579–86.

Amlung M, Sweet LH, Acker J, Brown CL, Mackillop J. Dissociable brain signatures of choice conflict and immediate reward preferences in alcohol use disorders. Addict Biol. 2014;19:743–53. Study examining the neural mechanisms of delayed reward discounting preferences in individuals with alcohol use disorders.

MacKillop J, Amlung M, Few L, Ray L, Sweet LH, Munafò M. Delayed reward discounting and addictive behavior: a meta-analysis. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2011;216:305–21. Meta-analysis of delay discounting results in the addictions.

Perry JL, Carroll ME. The role of impulsive behavior in drug abuse. Psychopharmacology. 2008;200:1–26.

De Wit H. Impulsivity as a determinant and consequence of drug use: a review of underlying processes. Addict Biol. 2009;14:22–31.

Dom G, D’Haene P, Hulstijn W, Sabbe B. Impulsivity in abstinent early- and late-onset alcoholics: differences in self-report measures and a discounting task. Addiction. 2006;101:50–9.

Kollins SH. Delay discounting is associated with substance use in college students. Addict Behav. 2003;28:1167–73.

Fernie G, Peeters M, Gullo MJ, Christiansen P, Cole JC, Sumnall H, et al. Multiple behavioural impulsivity tasks predict prospective alcohol involvement in adolescents. Addiction. 2013;108:1916–23.

Khurana A, Romer D, Betancourt LM, Brodsky NL, Giannetta JM, Hurt H. Working memory ability predicts trajectories of early alcohol use in adolescents: the mediational role of impulsivity. Addiction. 2013;108:506–15.

Tucker JA, Vuchinich RE, Rippens PD. Predicting natural resolution of alcohol-related problems: a prospective behavioral economic analysis. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2002;10:248–57.

Tucker JA, Vuchinich RE, Black BC, Rippens PD. Significance of a behavioral economic index of reward value in predicting drinking problem resolution. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2006;74:317–26.

Tucker JA, Foushee HR, Black BC. Behavioral economic analysis of natural resolution of drinking problems using IVR self-monitoring. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;16:332–40.

Tucker JA, Roth DL, Vignolo MJ, Westfall AO. A behavioral economic reward index predicts drinking resolutions: moderation revisited and compared with other outcomes. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2009;77:219–28.

Enoch M-A. The role of early life stress as a predictor for alcohol and drug dependence. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2011;214:17–31.

Fields S, Leraas K, Collins C, Reynolds B. Delay discounting as a mediator of the relationship between perceived stress and cigarette smoking status in adolescents. Behav Pharmacol. 2009;20:455–60.

Gray JC, Amlung MT, Acker JD, Sweet LH, MacKillop J. Item-based analysis of delayed reward discounting decision making. Behav Process. 2014;103C:256–60.

Koffarnus MN, Bickel WK. A 5-trial adjusting delay discounting task: accurate discount rates in less than one minute. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;22(3):222–8.

Anderson KG, Woolverton WL. Effects of clomipramine on self-control choice in Lewis and Fischer 344 rats. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2005;80:387–93.

Madden GJ, Smith NG, Brewer AT, Pinkston JW, Johnson PS. Steady-state assessment of impulsive choice in Lewis and Fischer 344 rats: between-condition delay manipulations. J Exp Anal Behav. 2008;90:333–44.

Stein JS, Pinkston JW, Brewer AT, Francisco MT, Madden GJ. Delay discounting in Lewis and Fischer 344 rats: steady-state and rapid-determination adjusting-amount procedures. J Exp Anal Behav. 2012;97:305–21.

Isles AR, Humby T, Walters E, Wilkinson LS. Common genetic effects on variation in impulsivity and activity in mice. J Neurosci. 2004;24:6733–40.

Anokhin AP, Golosheykin S, Grant JD, Heath AC. Heritability of delay discounting in adolescence: a longitudinal twin study. Behav Genet. 2011;41:175–83. Longitudinal twin study of the genetic and environmental influences on delayed reward discounting.

Eisenberg DTA, MacKillop J, Modi M, Beauchemin J, Dang D, Lisman SA, et al. Examining impulsivity as an endophenotype using a behavioral approach: a DRD2 Taql A and DRD4 48-bp VNTR association study. Behav Brain Funct. 2007;3(2). doi:10.1186/1744-9081-3-2.

Boettiger CA, Mitchell JM, Tavares VC, Robertson M, Joslyn G, D’Esposito M, et al. Immediate reward bias in humans: fronto-parietal networks and a role for the catechol-O-methyltransferase 158(Val/Val) genotype. J Neurosci. 2007;27:14383–91.

Smith CT, Boettiger CA. Age modulates the effect of COMT genotype on delay discounting behavior. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2012;222:609–17.

Paloyelis Y, Asherson P, Mehta MA, Faraone SV, Kuntsi J. DAT1 and COMT effects on delay discounting and trait impulsivity in male adolescents with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and healthy controls. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35:2414–26.

Gray JC, MacKillop J. Genetic basis of delay discounting in frequent gamblers: examination of a priori candidates and exploration of a panel of dopamine-related loci. Brain Behav. 2014; 4:812–24.

Hunt GM, Azrin NH. A community-reinforcement approach to alcoholism. Behav Res Ther. 1973;11:91–104.

Azrin NH. Improvements in the community-reinforcement approach to alcoholism. Behav Res Ther. 1976;14:339–48.

Meyers RJ, Miller WR. A community reinforcement approach to addiction treatment. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2001.

Smith JE, Meyers RJ, Delaney HD. The community reinforcement approach with homeless alcohol-dependent individuals. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1998;66:541–8.

Smith DC, Godley SH, Godley MD, Dennis ML. Adolescent community reinforcement approach outcomes differ among emerging adults and adolescents. J Subst Abuse Treat. 2011;41:422–30.

Miller WR, Wilbourne PL. Mesa Grande: a methodological analysis of clinical trials of treatments for alcohol use disorders. Addiction. 2002;97:265–77.

Roozen HG, Boulogne JJ, van Tulder MW, van den Brink W, De Jong CAJ, Kerkhof AJFM. A systematic review of the effectiveness of the community reinforcement approach in alcohol, cocaine and opioid addiction. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;74:1–13.

Meyers RJ, Roozen HG, Smith JE. The community reinforcement approach: an update of the evidence. Alcohol Res Health. 2011;33:380–8. In-depth review of the development of and empirical support for the CRA.

Dutcher LW, Anderson R, Moore M, Luna-Anderson C, Meyers R, Delaney HD, et al. Community reinforcement and family training (CRAFT): an effectiveness study. J Behav Anal Health Sports Fit Med. 2009;2:80–93.

Sisson RW, Azrin NH. Family-member involvement to initiate and promote treatment of problem drinkers. J Behav Ther Exp Psychiatry. 1986;17:15–21.

Miller WR, Meyers RJ, Tonigan JS. Engaging the unmotivated in treatment for alcohol problems: a comparison of three strategies for intervention through family members. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999;67:688–97.

Stitzer M, Petry N. Contingency management for treatment of substance abuse. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2006;2:411–34.

Petry NM, Alessi SM, Ledgerwood DM. A randomized trial of contingency management delivered by community therapists. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2012;80:286–98. Clinical study demonstrating the efficacy of contingency management when delivered by community therapists.

Petry NM, Martin B, Cooney JL, Kranzler HR. Give them prizes and they will come: contingency management for treatment of alcohol dependence. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68:250–7.

Prendergast M, Podus D, Finney J, Greenwell L, Roll J. Contingency management for treatment of substance use disorders: a meta-analysis. Addiction. 2006;101:1546–60.

McDonell MG, Howell DN, McPherson S, Cameron JM, Srebnik D, Roll JM, et al. Voucher-based reinforcement for alcohol abstinence using the ethyl-glucuronide alcohol biomarker. J Appl Behav Anal. 2012;45:161–5.

Barnett NP, Tidey J, Murphy JG, Swift R, Colby SM. Contingency management for alcohol use reduction: a pilot study using a transdermal alcohol sensor. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2011;118:391–9.

Sakai JT, Mikulich-Gilbertson SK, Long RJ, Crowley TJ. Validity of transdermal alcohol monitoring: fixed and self-regulated dosing. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2006;30:26–33.

Marques PR, McKnight AS. Field and laboratory alcohol detection with 2 types of transdermal devices. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33:703–11.

Bujarski S, MacKillop J, Ray LA. Understanding naltrexone mechanism of action and pharmacogenetics in Asian Americans via behavioral economics: a preliminary study. Exp Clin Psychopharmacol. 2012;20:181–90.

Campbell ANC, Nunes EV, Matthews AG, Stitzer M, Miele GM, Polsky D, et al. Internet-delivered treatment for substance abuse: a multisite randomized controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171:683–90.

Bickel WK, Yi R, Landes RD, Hill PF, Baxter C. Remember the future: working memory training decreases delay discounting among stimulant addicts. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:260–5.

Radu PT, Yi R, Bickel WK, Gross JJ, McClure SM. A mechanism for reducing delay discounting behavior by altering temporal attention. J Exp Anal Behav. 2011;96:363–85.

Daniel TO, Stanton CM, Epstein LH. The future is now: comparing the effect of episodic future thinking on impulsivity in lean and obese individuals. Appetite. 2013;71:120–5.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIH grants P30 DA027827 and the Peter Boris Chair in Addictions Research, which is held by Dr. MacKillop. The funders had no role in the content or preparation of the manuscript. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

ᅟ

Conflict of Interest

Joshua C. Gray and James MacKillop declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors. For all studies cited in the references on which JCG or JM were authors, all appropriate institutional review board approvals were obtained.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Alcohol

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Gray, J.C., MacKillop, J. Using Behavior Economics to Understand Alcohol Use Disorders: a Concise Review and Identification of Research Priorities. Curr Addict Rep 2, 68–75 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-015-0045-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-015-0045-z