Abstract

Background

To commence injury prevention efforts, it is necessary to understand the magnitude of the injury problem. No systematic reviews have yet investigated the extent of injuries in field hockey, despite the popularity of the sport worldwide.

Objective

Our objective was to describe the rate and severity of injuries in field hockey and investigate their characteristics.

Methods

We conducted electronic searches in PubMed, Embase, SPORTDiscus, and CINAHL. Prospective cohort studies were included if they were published in English in a peer-reviewed journal and observed all possible injuries sustained by field hockey players during the period of the study.

Results

The risk of bias score of the 22 studies included ranged from three to nine of a possible ten. In total, 12 studies (55%) reported injuries normalized by field hockey exposure. Injury rates ranged from 0.1 injuries (in school-aged players) to 90.9 injuries (in Africa Cup of Nations) per 1000 player-hours and from one injury (in high-school women) to 70 injuries (in under-21 age women) per 1000 player-sessions. Studies used different classifications for injury severity, but—within studies—injuries were included mostly in the less severe category. The lower limbs were most affected, and contusions/hematomas and abrasions were common types of injury. Contact injuries are common, but non-contact injuries are also a cause for concern.

Conclusions

Considerable heterogeneity meant it was not possible to draw conclusive findings on the extent of the rate and severity of injuries. Establishing the extent of sports injury is considered the first step towards prevention, so there is a need for a consensus on injury surveillance in field hockey.

Similar content being viewed by others

Substantial heterogeneity between studies prevents conclusive findings on the extent of the rate and severity of injuries in field hockey. |

Injury prevention efforts in field hockey may benefit from a consensus on the methodology of injury surveillance. |

1 Introduction

Field hockey is an Olympic sport played by men and women at both recreational and professional levels. The five continental and 132 national associations that are members of the International Hockey Federation [1] demonstrate the high level of popularity of field hockey worldwide. Field hockey participation may contribute to players’ health through the well-known benefits of regular exercise. However, participation in field hockey also entails a risk of injury [2].

In general, sports injuries result in individual and societal costs [3], hamper performance, and compromise a teams’ success over the sporting season [4, 5]. Therefore, injury prevention strategies are of great importance for teams at both recreational and professional levels. Establishing the extent of the injury problem is considered the first step towards effective prevention [6]. In field hockey, as well as in other sports, this information can aid researchers and health professionals in developing appropriate strategies to reduce and control injuries [6].

To the best of our knowledge, no systematic reviews have provided a synthesis of information on injuries sustained by field hockey players. Systematic reviews involve gathering evidence from different sources to enable a synthesis of what is currently known about a specific topic (e.g., injuries) and may facilitate the link between research evidence and optimal strategies for healthcare [7]. Therefore, the aim of this study was to systematically review the literature on injuries sustained by field hockey players, in order to describe the extent of such injuries in terms of rate and severity as well as to identify injury characteristics according to body location, type, and mechanism of injury.

2 Methods

2.1 Information Sources and Search Strategy

Electronic searches were conducted in PubMed, Exerpta Medical Database (Embase), SPORTDiscus, and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) databases with no limits on the publication date. The search strategy combined keywords for injury, field hockey, and study design: ((((((((((((injur*) OR traum*) OR risk*) OR overuse) OR overload) OR acute) OR odds) OR incidence) OR prevalence) OR hazard)) AND (((field AND hockey)) OR (hockey NOT ice))) AND (((prosp*) OR retrosp*) OR case*). The detailed search strategy for each database can be found Appendix S1 in the Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM). The last search was conducted on 31 May 2017.

2.2 Eligibility Criteria

Studies were eligible for inclusion if they were published in the English language in a peer-reviewed academic journal, were prospective cohort studies, and observed all possible injuries sustained by field hockey players during the period of the study (i.e., studies that looked only at specific injuries were not included). To minimize the possibility of recall bias, only prospective cohort studies were included [8, 9]. Studies were not included if they described field hockey injuries together with those from other sports, and specific data on field hockey could not be distinguished. Conference abstracts were not included.

2.3 Study Selection and Data Collection Process

Two reviewers (SDB and CJ) independently screened all records identified in the search strategy in two steps: title and abstract screening, and full-text screening. References of full texts were also screened for possible additional studies not identified in the four databases. Conflicts between reviewers’ decisions were resolved through discussion. A third reviewer (EV) was consulted for consensus rating when needed.

One reviewer (SDB) extracted the following information from the included studies: first author, publication year, country in which the study was conducted, primary objective, setting, follow-up period, number and description of field hockey players, injury definition, injury data collection procedure, number of injured players, number of injuries sustained by players during the study, and severity of injuries (Table 1). The number of injuries normalized by exposure to field hockey (i.e., injury rate) was also extracted. In addition, information on injury according to body location, type of injury, mechanism, and player position was gathered whenever possible. When different studies used the same dataset (Table 1), the results of such studies were combined in one row in all other tables for simplicity.

2.4 Risk of Bias Assessment

Two independent reviewers (SDB and CJ) assessed the risk of bias in the included studies using ten criteria previously used in systematic reviews on sports injury [9, 10]. All criteria were rated as 1 (i.e., low risk of bias) or 0 (i.e., high risk of bias). When insufficient information was presented in a study to rate a specific criterion as 1 or 0, the rating was categorized as ‘unable to determine’ (UD) and counted as 0. The assessment of each reviewer was compared, and conflicts were resolved through discussion. The ten criteria are described in Table 2.

3 Results

3.1 Search Results

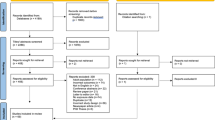

We retrieved 810 records from the four databases. Of those, 193 were duplicates. After screening 617 titles and abstracts and 21 full texts, ten studies matched the inclusion criteria. Screening the references of the full texts resulted in 12 additional records. In the end, 22 studies were included in the review. The flowchart of the inclusion process is presented in Fig. 1.

3.2 Description of the Included Studies

The characteristics of the 22 studies included in this review are presented in Table 1. Studies included in this review were published between 1975 and 2016, with 12 (55%) published before 2000 [11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22] and ten (45%) published from 2000 onwards [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. Two studies used the same dataset from the National Athletic Trainers’ Association (NATA) High School Injury database [21, 27], and two used the same dataset from the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) Injury Surveillance System [26, 28]. One study [24] was the follow-up of a previous study [23].

Six studies (27%) focused on describing field hockey injuries only [14, 18, 19, 28, 29, 32]. The other 16 studies (73%) described the epidemiology of injuries in field hockey together with those in other sports [11,12,13, 15,16,17, 20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27, 30, 31]. The period of follow-up varied between studies from a 6-day championship tournament [20] to 15 consecutive seasons of field hockey [28]. The sample size varied between 26 [22] and 5385 participants [28]. However, seven studies (32%) did not report the number of field hockey players studied [11, 13, 14, 19, 21, 25, 27].

The definition of injury varied across the studies. Common criteria to define an injury as recordable were a musculoskeletal condition requiring medical attention and/or leading to field hockey time loss (Table 1). The proportion (%) of injured players varied from 6% (in 7 months of high school) to 33% (in 6 days of university games). Twelve studies (55%) did not report the number or proportion of players who had sustained an injury over the study period [11,12,13,14,15, 18, 19, 25, 26, 28, 29, 32].

3.3 Risk-of-Bias Assessment

Table 2 shows the risk-of-bias assessment for the 22 included studies. The total score ranged from three to nine of a possible ten points. The studies published during and since 2000 scored higher (range 7–9) [23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31]. Three studies (14%) did not provide a clear definition of injury [11, 15, 18], and three did not describe any characteristics of the players studied [11, 15, 19]. These studies were published before the year 2000.

Nine studies (41%) included a random sample of players or studied the entire target population [12, 16, 20, 23,24,25, 30,31,32]. Eighteen studies (82%) collected injury data directly from players or medical professionals, 17 studies (77%) used only one method (i.e., not multiple methods) to collect injury data during the study [11, 13, 15,16,17,18,19,20, 23,24,25,26, 28,29,30,31,32], and one study (5%) did not describe the data collection procedure at all [14].

Twelve studies (55%) employed a medical professional to diagnose injuries [13, 16, 17, 21, 25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32]. The follow-up period of 13 studies (59%) was over 6 months [11,12,13,14, 17,18,19, 21, 24, 26,27,28,29], and 12 studies (55%) expressed ratios that represented both the number of injuries and the exposure to field hockey [11,12,13, 21, 23,24,25,26,27,28,29, 32].

3.4 Injury Extent in Field Hockey

3.4.1 Injury Rates

In total, 12 studies (55%) reported the number of injuries normalized by player exposure (i.e., injury rate). The injury rates reported in each of these studies are presented in Table 3, and were divided into two categories: (1) number of injuries per 1000 player-hours of field hockey exposure (i.e., time at risk) [11, 12, 23,24,25, 32] and (2) number of injuries per 1000 player-sessions (i.e., sessions at risk) [13, 21, 25,26,27,28,29]. One study reported the number of injuries according to both player-hours and player-sessions at risk [25].

In the studies describing injuries according to players’ time at risk, injury rates ranged from 0.1 injuries (in school-aged players) [12] to 90.9 injuries (in Africa Cup of Nations) [32] per 1000 player-hours of field hockey (Table 3). The injury rate in the studies describing injuries according to players’ sessions at risk varied from one injury (in high-school women) [13] to 70 injuries (in under-21 age women) [29] per 1000 player-sessions. The injury rates were higher in games than in training sessions in two [21, 28] of the three studies that investigated this outcome [21, 28, 29]. In major tournaments, injury rates were higher in men [25, 32].

3.4.2 Injury Severity

Table 1 presents the classification of injuries according to severity. Most of the studies (55%) used field hockey time loss to report the severity of injuries [11, 13, 17, 19, 21, 25,26,27,28,29,30,31], but reported the days of time loss differently. Some studies reported the average days of time loss [11, 17] and others used diverse cut-off points to report injury-related days of time loss, such as two days [19], eight days [21, 27], and ten days [26, 28]. The majority of injuries were in the less severe category in all studies reporting days of time loss due to injury, regardless of the cut-off points used [13, 14, 19, 21, 25, 28, 29, 31]. Six studies (27%) included severity measures in the methodology but did not specify the number or proportion of injuries according to severity in the results [12, 16, 20, 23, 24, 32]. Three studies (14%) did not mention severity of injury at all [15, 18, 22].

3.5 Injury Characteristics in Field Hockey

3.5.1 Body Location and Types of Injury

Fifteen studies (68%) described injuries according to the affected body location [12,13,14,15,16, 18, 19, 21, 24, 25, 27,28,29, 31, 32]. Table 4 presents the proportion (%) of injuries according to body location reported in these studies. The most common site of injury was the lower limbs (ranging from 13% [25] to 77% [18] of all injuries), followed by head (2% [13] to 50% [25]), upper limbs (0% [16] to 44% [12]), and trunk (0% [18] to 16% [28]). In the lower limbs, injuries were more frequent in the knee, ankle, lower leg, and thigh (Table 4).

In total, 13 studies (59%) described the types of injury sustained by field hockey players [13,14,15,16, 18, 20, 21, 24, 25, 27,28,29, 31]. Table 5 presents the proportion (%) of injuries according to their type. Contusions and hematomas were the most common types of injury (ranging from 14% [31] to 64% [18] of all injuries), followed by abrasions and lacerations (5% [14] to 51% [15]), sprains (2% [18] to 37% [13]) and strains (0% [25] to 50% [28]). Concussions ranged from 0% [25] to 25% [25].

3.5.2 Injury According to Mechanism and Player Position

Eight studies (36%) described injuries according to their mechanism [18,19,20, 25, 28, 29, 31, 32]. Table 6 presents the proportion (%) of injuries according to their mechanism. Non-contact injuries ranged from 12% [18] to 64% [28]. Contact with the ball (range: 2% [29] to 52% [32]) and stick (9% [29] to 27% [18]) were also common mechanisms, as was contact with another player (2% [19] to 45% [20]) or with the ground (9% [28] to 15% [20]).

Three studies (14%) reported injuries according to the injured player’s position [19, 28, 29]. Goalkeepers sustained fewer injuries in all three studies that reported injuries by playing position (4% [19] to 19% [28]). Defenders sustained 16% [19] to 36% [29] of injuries, while midfielders and forwards sustained 22% [28] to 37% [19] (Table 7).

4 Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first systematic review to summarize the descriptive evidence of injuries sustained by field hockey players. We included only prospective studies to ensure we gathered the most reliable information available on the extent of injuries in field hockey in terms of rate and severity as well as injury characteristics according to body location, type, and mechanism of injury. To reduce and control field hockey injuries, as for all sports, we must first establish the extent of the injury problem [6]. The substantial heterogeneity between studies included in this review prevented conclusive findings on the extent of the rate and severity of injuries in field hockey (Tables 1, 2). Such heterogeneity may be caused by the different definitions and methods employed to record and report injuries and the different characteristics and levels of players studied.

This systematic review shows that, despite the long history of field hockey and its popularity worldwide, prospective studies focusing on overall field hockey injuries are still lacking. The majority of the studies investigated field hockey injuries together with injuries in other sports [11,12,13, 15,16,17, 20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27, 30, 31]. Within such studies, injury rates in field hockey were comparable to those in other team sports, such as basketball [23, 24, 26], netball [23, 24], lacrosse [26], and softball [21, 27]. The injury rate in field hockey can be considered low compared with football (soccer) [21, 25,26,27]. However, in major tournaments, the rate of time loss injuries in field hockey [32] can be considered higher than that in football (soccer) [4]. These findings confirm that the risk of sustaining an injury in field hockey should not be neglected.

Despite the considerable heterogeneity between studies, it is still possible to observe similar characteristics of injuries with regard to body location, type, and mechanism of injury. Most of the injuries described in the studies included in this review were to the lower limbs (Table 4), affecting mainly the knee and the ankle. This is in line with previous studies on team sports involving running and stepping maneuvers, such as football (soccer) [33] and lacrosse [34], and justifies a focus on preventive efforts in this body area. Interestingly, the majority of injuries sustained by women during major tournaments were to the head [25, 32]. A specific analysis of head injuries in collegiate women’s field hockey showed that 48% of these injuries occurred due to contact with an elevated ball [35]. Most (39%) of the concussions were due to direct contact with another player, and 25% were due to contact with an elevated ball [35].

Contusions and hematomas were common types of injury, as were abrasions and lacerations, which might be due to players’ contact with the ball, stick, and playing surface [2, 28]. A specific analysis of ball-contact injuries in 11 collegiate sports showed that injury rates were the highest in women’s softball, followed by women’s field hockey and men’s baseball [36]. In field hockey, the common activities associated with ball-contact injuries were defending, general play, and blocking shots [36]. To reduce the injury burden, the International Hockey Federation stated that goalkeepers must wear protective equipment comprising at least headgear, leg guards, and kickers [37]. Field players are recommended to use shin, ankle, and mouth protection [37], and other research suggested that the use of such equipment should be mandatory [2]. Accordingly, some national associations have updated their rules to make shin, ankle, and mouth protection obligatory [38, 39].

It is important to note that non-contact injuries are also a cause for concern in field hockey (Table 6). Although protective equipment has a fundamental role in injury prevention, it may not prevent most of the non-contact injuries. During the last decades, different studies have shown that it is possible to prevent injuries in team sports with structured exercise [40,41,42,43,44]. Yet, to our knowledge, evidence showing the implementation of such programs in field hockey is lacking. Nevertheless, exercise programs that have proven effective in preventing sports injury can be introduced as part of the regular training schedule of the field hockey team, especially programs focusing on the prevention of lower limb injuries [40,41,42]. While there is no structured exercise program for field hockey, stakeholders can also use open source resources for overall and specific injury prevention that are supported by the International Olympic Committee, such as exercise programs and guidelines on load management and youth athletic development [45,46,47].

4.1 Future Recommendations

The present systematic review shows that studies have used different definitions and methods to record and classify injuries and their severity, and this prevents conclusive findings on the extent of the injury problem in field hockey. As establishing the extent of sports injury is considered the first step toward effective prevention [6], one of the main findings of this review is the recognition of the need for a consensus on the methodology of injury surveillance in field hockey. Consensus statements on the methodology of injury surveillance have been made available for a variety of sports [8, 48,49,50,51,52,53,54]. A consensus statement represents the result of a comprehensive collective analysis, evaluation, and opinion of a panel of experts regarding a specific subject (e.g., methodology of injury surveillance in field hockey) [55]. Consequently, consensus statements enable investigators from different settings to access and employ the same definitions and methods to collect and report injury data. Comparisons among different studies as well as data pooling for meta-analyses are then facilitated.

The common goal in field hockey is to promote players’ safety while maintaining the traditions of the sport [35]. Protecting the health of the athletes is also a priority of the International Olympic Committee [56], and resources for injury prevention have been made available for the public in general [45,46,47]. The field hockey community would benefit from studies investigating the implementation of such resources and from strategies that have been proven to be effective in other sports [40,41,42,43,44]. Until there is consensus on the methodology of injury surveillance in field hockey, investigators may use consensus from other team sports in future studies as an example [8, 52, 53]. Based on the gaps identified in the studies included in this review, the authors also suggest that future studies adhere to the reporting guidelines from the Enhancing the Quality and Transparency of Health Research (EQUATOR) Network. The EQUATOR Network provides comprehensive documentation on what information needs to be reported in scientific manuscripts depending on the study design [57]. By following an appropriate guideline such as that of the EQUATOR Network, future investigators will facilitate assessment of the generalizability, strengths, and limitations of studies on field hockey injuries.

4.2 Limitations

Electronic searches were conducted in four databases that were considered relevant for this systematic review. This does not rule out the possibility of eligible articles published in journals that were not indexed in any of these databases. To minimize this limitation, we screened the references of the full texts assessed for eligibility and included additional studies that were not identified in the database search. In addition, this systematic review included only scientific manuscripts published in English, although studies on field hockey injuries have been published in other languages. These were not included because the authors were unable to translate the papers accurately enough to extract their data.

5 Conclusion

The present systematic review shows that, despite the long history and the popularity of field hockey worldwide, few prospective studies have investigated the overall injury problem in field hockey. Most of the information on field hockey injuries registered prospectively comes from studies conducted in multi-sport settings. The range of definitions, methods, and reporting employed by studies prevents conclusive findings on the rate and severity of injuries in field hockey. To facilitate the development of evidence-based strategies for injury prevention, field hockey may benefit from a consensus on the methodology of injury surveillance. While no specific consensus is available for field hockey, future studies may use widely accepted consensus from other sports, such as football (soccer). In addition, future studies on field hockey injuries are encouraged to adhere to the reporting guidelines from the EQUATOR Network.

Despite the considerable heterogeneity, it is clear that most of the injuries sustained by field hockey players affect the lower limbs, justifying efforts to develop preventive strategies for this body area. Contact injuries, such as contusions/hematomas, and abrasions, are frequent, and the use of protective equipment for the ankle, shin, hand, mouth, and eye/face has been recommended. Nevertheless, non-contact injuries are also common in field hockey, and most of these may not be prevented by protective gear. To reduce the burden of injuries, field hockey stakeholders may implement exercise-based injury-prevention programs and guidelines on load management and youth athletic development that have been supported by the International Olympic Committee.

Change history

14 February 2018

Page 1: The listing of the author names and affiliations, which previously read.

References

International Hockey Federation. http://www.fih.ch/hockey-basics/history/. Accessed 2 Aug 2017.

Murtaugh K. Field hockey injuries. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2009;8:267–72. https://doi.org/10.1249/JSR.0b013e3181b7f1f4.

van Mechelen W. The severity of sports injuries. Sport Med. 1997;24:176–80. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-199724030-00006.

Hägglund M, Waldén M, Magnusson H, et al. Injuries affect team performance negatively in professional football: an 11-year follow-up of the UEFA Champions League injury study. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47:738–42. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2013-092215.

Eirale C, Tol JL, Farooq A, et al. Low injury rate strongly correlates with team success in Qatari professional football. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47:807–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2012-091040.

van Mechelen W, Hlobil H, Kemper HCG. Incidence, severity, aetiology and prevention of sports injuries. Sport Med. 1992;14:82–99. https://doi.org/10.2165/00007256-199214020-00002.

Cook DJ. Systematic reviews: synthesis of best evidence for clinical decisions. Ann Intern Med. 1997;126:376. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-126-5-199703010-00006.

Fuller CW, Molloy MG, Bagate C, et al. Consensus statement on injury definitions and data collection procedures for studies of injuries in rugby union. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41:328–31. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2006.033282.

Weiler R, Van Mechelen W, Fuller C, et al. Sport injuries sustained by athletes with disability: a systematic review. Sports Med. 2016;46:1141–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0478-0.

Lopes AD, Hespanhol Júnior LC, Yeung SS, et al. What are the main running-related musculoskeletal injuries? A systematic review. Sports Med. 2012;42:891–905. https://doi.org/10.2165/11631170-000000000-00000.

Weightman D, Browne RC. Injuries in eleven selected sports. Br J Sports Med. 1975;9:136–41. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.9.3.136.

Zaricznyj B, Shattuck LJM, Mast TA, et al. Sports-related injuries in school-aged children. Am J Sports Med. 1980;8:318–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/036354658000800504.

Clarke KS, Buckley WE. Women’s injuries in collegiate sports. A preliminary comparative overview of three seasons. Am J Sports Med. 1980;8:187–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/036354658000800308.

Rose CP. Injuries in women’s field hockey: a four-year study. Phys Sports Med. 1981;9:97–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913847.1981.11711034.

Mathur DN, Salokun SO, Uyanga DP. Common injuries among Nigerian games players. Br J Sports Med. 1981;15:129–32. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7272655.

Martin RK, Yesalis CE, Foster D, et al. Sports injuries at the 1985 Junior Olympics. An epidemiologic analysis. Am J Sports Med. 1987;15:603–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/036354658701500614.

McLain LG, Reynolds S. Sports injuries in a high school. Pediatrics. 1989;84:446–50.

Jamison S, Lee C. The incidence of female hockey injuries on grass and synthetic playing surfaces. Aust J Sci Med Sport. 1989;21:15–7.

Fuller MI. A study of injuries in women’s field hockey as played on synthetic turf pitches. Physiother Sport. 1990;12:3–6.

Cunningham C, Cunningham S. Injury surveillance at a national multi-sport event. Aust J Sci Med Sport. 1996;28:50–6.

Powell JW, Barber-Foss KD. Injury patterns in selected high school sports: a review of the 1995–1997 seasons. J Athl Train. 1999;34:277–84.

Fawkner HJ, McMurrary NE, Summers JJ. Athletic injury and minor life events: a prospective study. J Sci Med Sport. 1999;2:117–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1440-2440(99)80191-1.

Stevenson MR, Hamer P, Finch CF, et al. Sport, age, and sex specific incidence of sports injuries in Western Australia. Br J Sports Med. 2000;34:188–94.

Finch C, Da Costa A, Stevenson M, et al. Sports injury experiences from the Western Australian sports injury cohort study. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2002;26:462–7. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-842X.2002.tb00348.x.

Junge A, Langevoort G, Pipe A, et al. Injuries in team sport tournaments during the 2004 Olympic Games. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:565–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546505281807.

Hootman JM, Dick R, Agel J. Epidemiology of collegiate injuries for 15 sports: summary and recommendations for injury prevention initiatives. J Athl Train. 2007;42:311–9.

Rauh MJ, Macera CA, Ji M, et al. Subsequent injury patterns in girls’ high school sports. J Athl Train. 2007;42:486–94.

Dick R, Hootman JM, Agel J, et al. Descriptive epidemiology of collegiate women’s field hockey injuries: National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance System, 1988–1989 through 2002–2003. J Athl Train. 2007;42:211–20.

Rishiraj N, Taunton JE, Niven B. Injury profile of elite under-21 age female field hockey players. J Sports Med Phys Fitness. 2009;49:71–7.

Junge A, Engebretsen L, Mountjoy ML, et al. Sports injuries during the Summer Olympic Games 2008. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:2165–72. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546509339357.

Engebretsen L, Soligard T, Steffen K, et al. Sports injuries and illnesses during the London Summer Olympic Games 2012. Br J Sports Med. 2013;47:407–14. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2013-092380.

Theilen T-M, Mueller-Eising W, Wefers Bettink P, et al. Injury data of major international field hockey tournaments. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:657–60. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-094847.

Faude O, Rössler R, Junge A. Football injuries in children and adolescent players: are there clues for prevention? Sports Med. 2013;43:819–37. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-013-0061-x.

Putukian M, Lincoln AE, Crisco JJ. Sports-specific issues in men’s and women’s lacrosse. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2014;13:334–40. https://doi.org/10.1249/JSR.0000000000000092.

Gardner EC. Head, face, and eye injuries in collegiate women’s field hockey. Am J Sports Med. 2015;43:2027–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546515588175.

Fraser MA, Grooms DR, Guskiewicz KM, et al. Ball-contact injuries in 11 National Collegiate Athletic Association Sports: the injury surveillance program, 2009–2010 through 2014–2015. J Athl Train 2017;1062–6050–52.3.10. https://doi.org/10.4085/1062-6050-52.3.10.

International Hockey Federation. Rules of Hockey. http://www.fih.ch/inside-fih/our-official-documents/rules-of-hockey/. Accessed 27 June 2017.

National Collegiate Athletic Association. Field hockey rules modifications. http://www.ncaa.org/championships/playing-rules/field-hockey-rules-game.

Koninklijke Nederlandse Hockey Bond. Spelreglement Veldhockey; 2017. https://www.knhb.nl/kenniscentrum/scheidsrechters/alles-over-de-spelregels.

Olsen O-E, Myklebust G, Engebretsen L, et al. Exercises to prevent lower limb injuries in youth sports: cluster randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2005;330:449. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38330.632801.8F.

Verhagen E, van der Beek A, Twisk J, et al. The effect of a proprioceptive balance board training program for the prevention of ankle sprains: a prospective controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32:1385–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546503262177.

Al Attar WSA, Soomro N, Sinclair PJ, et al. Effect of injury prevention programs that include the Nordic hamstring exercise on hamstring injury rates in soccer players: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Med. 2017;47:907–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-016-0638-2.

Thorborg K, Krommes KK, Esteve E, et al. Effect of specific exercise-based football injury prevention programmes on the overall injury rate in football: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the FIFA 11 and 11+ programmes. Br J Sports Med. 2017;51:562–71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-097066.

Longo UG, Loppini M, Berton A, et al. The FIFA 11+ program is effective in preventing injuries in elite male basketball players: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Am J Sports Med. 2012;40:996–1005. https://doi.org/10.1177/0363546512438761.

Verhagen E. Get Set: prevent sports injuries with exercise! Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:762. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-094644.

Soligard T, Schwellnus M, Alonso J-M, et al. How much is too much? (Part 1) International Olympic Committee consensus statement on load in sport and risk of injury. Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:1030–41. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2016-096581.

Bergeron MF, Mountjoy M, Armstrong N, et al. International Olympic Committee consensus statement on youth athletic development. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49:843–51. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-094962.

Yamato TP, Saragiotto BT, Lopes AD. A consensus definition of running-related injury in recreational runners: a modified Delphi approach. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2015;45:375–80. https://doi.org/10.2519/jospt.2015.5741.

Mountjoy M, Junge A, Alonso JM, et al. Consensus statement on the methodology of injury and illness surveillance in FINA (aquatic sports). Br J Sports Med. 2016;50:590–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2015-095686.

Turner M, Fuller CW, Egan D, et al. European consensus on epidemiological studies of injuries in the thoroughbred horse racing industry. Br J Sports Med. 2012;46:704–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2011-090312.

Pluim BM, Fuller CW, Batt ME, et al. Consensus statement on epidemiological studies of medical conditions in tennis, April 2009. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:893–7. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2009.064915.

Fuller CW, Ekstrand J, Junge A, et al. Consensus statement on injury definitions and data collection procedures in studies of football (soccer) injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2006;40:193–201. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsm.2005.025270.

Orchard J, Newman D, Stretch R, et al. Methods for injury surveillance in international cricket. J Sci Med Sport. 2005;8:1–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1440-2440(05)80019-2.

Timpka T, Alonso J-M, Jacobsson J, et al. Injury and illness definitions and data collection procedures for use in epidemiological studies in Athletics (track and field): consensus statement. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:483–90. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2013-093241.

Consensus statements. Diabetes Care 2002;25:S139. https://doi.org/10.2337/diacare.25.2007.s139.

Engebretsen L, Bahr R, Cook JL, et al. The IOC Centres of Excellence bring prevention to sports medicine. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48:1270–5. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2014-093992.

The EQUATOR Network. Enhancing the QUAlity and Transparency Of Health Research. http://www.equator-network.org/. Accessed 2 July 2017.

Acknowledgements

Saulo Delfino Barboza is a PhD candidate supported by CAPES (Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior), Brazilian Ministry of Education (process number 0832/14-6).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

This study had no funding sources.

Conflict of interest

Saulo Delfino Barboza, Corey Joseph, Joske Nauta, and Evert Verhagen have no conflicts of interest. Willem van Mechelen is the editor and chapter co-author of the Oxford Textbook of Children’s Sport and Exercise Medicine (Armstrong N, van Mechelen W. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2017. ISBN 9780198757672).

Additional information

A correction to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-018-0873-9.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Barboza, S.D., Joseph, C., Nauta, J. et al. Injuries in Field Hockey Players: A Systematic Review. Sports Med 48, 849–866 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0839-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0839-3