Abstract

Introduction

Intravenous levetiracetam (IV LEV) is approved for treatment status epilepticus (SE). However, the drug’s high cost must be considered when deciding on a treatment strategy. This study aimed to compare the efficacy of brand-name and generic IV LEV for acute repetitive convulsive seizure (ARCS) or SE.

Methods

Forty patients aged 18 years or older who had been diagnosed with SE or ARCS were included in this double-blind study. Patients were randomly assigned at a 1:1 ratio (via computer-generated code) to receive either brand-name or generic IV LEV. The primary outcomes were seizure control and the number of seizure exacerbations during the 24 h after drug administration, while the secondary outcomes were electroencephalographic (EEG) findings, serious adverse events, and clinical outcome at hospital discharge.

Results

Forty patients were randomly assigned administration with either brand-name IV LEV (10 SE and 10 ARCS patients) or generic IV LEV; 7 SE and 13 ARCS patients). There was no significant difference in patients’ baseline characteristics. The seizure control rate was 75% in the brand-name IV LEV group and 65% in the generic IV LEV group (p value: 0.490). Five (25%) patients in the brand-name IV LEV group, and six (30%) patients in the generic IV LEV group developed seizure exacerbations within 24 h after drug administration (p value 0.723). There were no reports of drug-related adverse events. Two of the patients taking brand-name IV LEV and one taking the generic IV LEV died (p value > 0.999).

Conclusion

Treatment with the generic IV LEV had comparable outcomes with brand-name IV LEV. The generic IV LEV may be an alternative medication for the treatment of SE and ARCS to reduce treatment costs.

Trial Registration

TCTR20190513001.

Funding

Great Eastern Drug Company.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

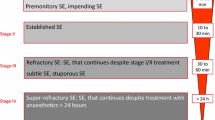

Status epilepticus (SE) and acute repetitive convulsive seizure (ARCS) are the most common neurological emergencies and require immediate and proper management in order to prevent significant irreversible neuronal damage. The current algorithm used for treatment of these conditions has benzodiazepines as the first line of treatment, followed by phenytoin, fosphenytoin, valproate, and levetiracetam (LEV) [1,2,3,4,5].

Levetiracetam is a novel broad-spectrum antiepileptic. Its mechanism of seizure control is that it binds to the synaptic vesicle protein SV2A without central nervous system depression. It has high safety profiles in patients with renal, hepatic, and cardiac impairment. Owing to these favorable properties, LEV has become the preferred antiepileptic drug (AED) for treating SE and ARCS. However, the high cost of intravenous LEV (IV LEV) has limited its availability, particularly in developing countries.

Although many generic drugs have been shown to be as safe and effective as brand-name medications, randomized controlled trials are required for each drug to confirm that this is the case [6]. AEDs are a type of generic medications that may require more attention on using generic medications due to increasing risk of treatment failure [6]. Generic carbamazepine may not be equal bioequivalent with the brand-name one [6]. Although there has been a generic version of IV LEV (Focale®) available for several years, there have been few clinical studies comparing it with brand-name IV LEV (Keppra®). This study, thus, compared brand-name and generic IV LEV in terms of efficacy and safety in patients with SE or ACRS.

Methods

This study was a randomized, double-blind noninferiority trial conducted at Khon Kaen University in Thailand. The inclusion criteria were being 18 years or older, having been diagnosed with SE or ARCS according to the 1981 International Classification of Epileptic Seizures, and seizures that were uncontrolled after treatment with more than two doses of intravenous phenytoin, fosphenytoin, or valproate. Patients were excluded if they had a history of behavioral change, depression, attempted suicide, neutropenia (defined as neutrophil count < 1500 cell/µL), or treatment with carbamazepine. Patients were also excluded if they were currently pregnant or lactating or if the cause of their seizures were electrolyte imbalance or severe hyperglycemia.

All eligible patients gave informed consent prior to study participation. In cases in which the patient was unable to give informed consent, a legal representative did so on behalf of the patient. After initial clinical evaluation, the patients were randomly assigned a treatment using a block of four method. The clinical research unit gave each patient either brand name (Keppra®) or generic (Focale®) IV LEV (at a 1:1 ratio) from a sealed envelope. The medication was administered intravenously at a dose of 20 mg/kg in 100 ml of 5% dextrose water over the course of 30 min [6]. The study medications were provided by the sponsor company. Both Focale® and Keppra® have been tested for pharmacological properties. There is no significant difference between both agents including administration vehicle.

The primary outcome of this study was the rate of seizure control at 24–48 h and recurrent seizures at 24 h after IV LEV administration. The seizure control after loading at 24 and 48 h indicated no seizure after IV LEV loading until 24 and 48 h, respectively. The secondary outcomes were EEG results at 48 and 72 h after treatment and clinical outcomes at discharge. Safety, tolerability, and serious adverse events were recorded. A serious adverse event was defined as death, a life-threatening condition, hospitalization, disability, or other medically significant events. Seizure control and recurrent seizures were defined by the presence of seizures as confirmed clinically and/or using EEG. Clinical outcomes at discharge were evaluated by an attending physician and categorized as complete recovery, improved, not improved, against advice, or death.

The protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethic committee in human research, Khon Kaen University, Thailand (HE 601322). The study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. The eligible participants gave an informed consent prior to the study participation.

Sample Size Calculation

There is no previous placebo-controlled trials conducted using brand-name IV LEV, the sample size calculation was based on the 25% difference in seizure control rate between brand-name and generic IV LEV [7]. A previous study showed that the seizure control rate in adults with SE was 76.6% [8]. Based on a confidence interval of 95% and power of 80%, the required sample size was 44 patients.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive statistics were used to compare clinical factors at baseline and all clinical outcomes between both groups. Numerical variables were compared using a student t test or Wilcoxson rans sum test when data were normally-distributed and non-normally distributed, respectively. A Chi square or Fisher Exact test was used to compare categorical variables between the two studied groups. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA version 10.0 (College Station, Texas, USA).

Results

Between April 2018 and February 2019, there were 40 patients who met the study criteria and participated in the study. The patients were randomly assigned to one of two groups. Half of the patients were assigned brand-name IV LEV (Keppra®) and the other half were given a generic version of the drug (Focale®). Baseline characteristics, indications of IV LEV, and laboratory results were comparable between the two groups (Table 1). The average age in the generic IV LEV group was slightly higher than that in the brand-name IV LEV group (63.5 vs 61.5 years; p value 0.379), but the difference was not statistically significant. Causes of seizure disorders in both groups were comparable and shown in Table 1 (p value 0.581). There was also no statistically significant difference in terms of baseline kidney or liver function. The mean serum creatinine levels in the brand-name and generic groups were 1.63 mg/dL and 1.80 mg/dL, respectively (p value = 0.95), and mean serum alanine aminotransferase (ALT)/serum aspartate aminotransferase (AST) levels were 39.70/72.35 and 32.28/53.89, respectively (p value = 0.500/0.756). The baseline EKG as normal sinus rhythms were also comparable between the two groups (p value = 0.613).

There were 10 patients (50.00%) with SE in the brand-name IV LEV group and 7 (35.00%) in the generic group (p value: 0.337). The average loading dose of IV LEV (1000 mg; p value: 0.398) and numbers of patients who underwent re-loading treatment (4 [20.00%] in the brand-name group and 7 [35.00%] in the generic group; p value: 0.288) were comparable between the two groups (Table 1). The two groups were also similar in terms of all clinical outcomes and side-effects (Table 2). The seizure control rate was slightly higher in the brand-name IV LEV group than in the generic IV LEV group at 24 h (75.00% vs 65.00%; p value 0.490) but the rates were the same (75.00%) at 48 h (p value > 0.999), as shown in Table 1. The recurrent seizure rates at 24 h after treatment were also similar in the two groups. Although it was slightly higher in the generic group, this difference was not statistically significant (30.00% vs 25.00%; p value 0.723). The mortality rate was slightly higher in the brand-name IV LEV group than in the generic IV LEV group (10.00% vs 5.00%; p value > 0.999).

Discussion

Previous studies have shown brand-name IV LEV to be an effective treatment for SE, with a seizure control rate ranging from 59.1 to 76.6% [8,9,10,11]. This study found that patients taking brand-name IV LEV had a seizure control rate of 75% at 24 h after administration. Although generic IV LEV led to a slightly lower seizure control rate at 24 h after treatment, it was equal to brand-name IV LEV in this respect (75%) at 48 h after treatment, and was within the range of the rates found in previous reports (65% vs 59.1–76.6%) [8,9,10,11]. The generic IV LEV also had comparable outcomes in terms of recurrent seizures at 24 h, EEG outcomes, discharge outcomes, mortality rate, major side effects, and length of hospital stay (Table 2). This suggests that generic IV LEV was equally effective as the brand-name version of the drug.

Regarding safety, the results showed that neither brand-name nor generic IV LEV exhibited any serious side effects. These results were supported by those of previous published studies [8,9,10]. For example, one study found that there were no serious adverse reactions from IV LEV in 18 children and 37 adults with SE. The mortality rate of SE from IV LEV in this study was comparable with that from a previous study [9]. Patients given generic IV LEV in our study had somewhat lower mortality rate than those given brand-name IV LEV (5% vs 10%) and than that found in the previous study (5% vs 9.09%). However, these differences were not statistically significant or clinically different. Note that the generic IV LEV group had a lower mortality rate than the brand-name group despite its patients having a higher average age (63.5 vs 61.5 years) and a higher proportion of re-loading, indicating more severe cases (35% vs 20%), as shown in Table 1.

The strength of this study was that it was a randomized controlled trial. We chose this study design as a placebo-controlled study would not have been ethical to conduct. There were some limitations, however. First, we were forty patients short of the required sample size. Second, we enrolled both patients with SE and those with ACRS (SE accounted for 42.5%). Third, seizure controlled times are not recorded in this study. Those two primary outcomes, seizure control rate at 24 and 48 h, defined by no seizure after IV LEV loading through 24 and 48 h. All seizure control patients are those who had no seizure after IV LEV loading. The duration times of seizures prior to IV LEV treatment were also not evaluated. However, both groups received IV LEV treatment by similar study protocol. We assumed that both groups were given the study drugs by comparable times to IV LEV treatment. Finally, even though we used the 1981 ILAE criteria to diagnose SE or ACRS, intravenous antiepileptic drugs were given if there is more than 5 min of continuous seizures or incomplete recovery between two discrete seizure episodes.

Conclusion

Generic IV LEV may be an alternative option for the treatment patients with SE or ARCS as brand-name IV LEV.

References

Bachhuber A, Lasrich M, Halmer R, Fassbender K, Walter S. Comparison of antiepileptic approaches in treatment of benzodiazepine nonresponsive status epilepticus. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2016;22:178–83.

Betjemann JP, Lowenstein DH. Status epilepticus in adults. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14:615–24.

Brigo F, Bragazzni N, Nardone R, Trinka E. Direct and indirect comparison meta-analysis of levetiracetam versus phenytoin or valproate for convulsive status epilepticus. Epilepsy Behav. 2016;64:110–5.

Grover EH, Nazzal Y, Hirsch LJ. Treatment of convulsive status epilepticus. Curr Treat Opt Neurol. 2016;18:11–31.

Mundlamuri RC, Sinha S, Subbakrishna DK, Prathyusha PV, Nagappa M, Bindu PS, et al. Management of generalized convulsive status epilepticus (SE): a prospective randomized controlled study of combined treatment with intravenous lorazepam with either phenytoin, sodium valproate or levetiracetam—pilot study. Epilepsy Res. 2015;114:52–8.

Lewek P, Kardas P. Generic drugs: the benefits and risks of making the switch. J Fam Pract. 2010;59:634–40.

Hahn S. Understanding noninferiority trials. Korean. J Pediatr. 2012;55:403–7.

Atmaca MM, Orhan EK, Bebek N, Gurses C. Intravenous levetiracetam treatment in status epilepticus: a prospective study. Epilepsy Res. 2015;114:13–22.

Chakravarthi S, Goyal MK, Modi M, Bhalla A, Singh P. Levetiracetam versus phenytoin in management of status epilepticus. J Clin Neurosci. 2015;22:959–63.

Khongkhatithum C, Thampratankul L, Wiwattanadittakul N, Visudtibhan A. Intravenous levetiracetam in Thai children and adolescents with status epilepticus and acute repetitive seizures. Eur J Paediatr Neurol. 2015;19:429–34.

Thongplew S, Chawsamtong S, Sawanyawisuth K, Tiamkao S. Intravenous levetiracetam treatment in Thai adults with status epilepticus. Neurol Asia. 2013;18:167–75.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the participants of the study, and the Integrated Epilepsy Research Group, and Sleep Apnea Research Group, Khon Kaen University, Thailand.

Funding

This study was funded by the Great Eastern Drug Company, which provided the studied medications for all patients but was not involved in any other aspect of the study (study design, data collection, data analysis, presentation of results, or manuscript preparation). The Great Eastern Drug Company also funded the journal’s Rapid Service Fee. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Rachot Wongjirattikarn, Kittisak Sawanyawisuth, Sineenard Pranboon, Siriporn Tiamkao and Somsak Tiamkao have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

The protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethics committee in human research, Khon Kaen University, Thailand (HE 601322). The study was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. The eligible participants gave an informed consent prior to the study participation.

Data Availability

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to: https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.9159494.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Wongjirattikarn, R., Sawanyawisuth, K., Pranboon, S. et al. Can Generic Intravenous Levetiracetam Be Used for Acute Repetitive Convulsive Seizure or Status Epilepticus? A Randomized Controlled Trial. Neurol Ther 8, 425–431 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-019-00150-x

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40120-019-00150-x