Abstract

The prevention of overweight in childhood is paramount to long-term heart health. Food marketing predominately promotes unhealthy products which, if over-consumed, will lead to overweight. International health expert calls for further restriction of children’s exposure to food marketing remain relatively unheeded, with a lack of evidence showing a causal link between food marketing and children’s dietary behaviours and obesity an oft-cited reason for this policy inertia. This direct link is difficult to measure and quantify with a multiplicity of determinants contributing to dietary intake and the development of overweight. The Bradford Hill Criteria provide a credible framework by which epidemiological studies may be examined to consider whether a causal interpretation of an observed association is valid. This paper draws upon current evidence that examines the relationship between food marketing, across a range of different media, and children’s food behaviours, and appraises these studies against Bradford Hill’s causality framework.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Papers of particular interest, published recently, have been highlighted as: • Of importance

Mendis, S., P. Puska, and B. Norrving, Global atlas on cardiovascular disease prevention and control. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011.

World Health Organization. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010. Description of the global burden of NCDs, their risk factors and determinants. 2011.

World Health Organization. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of chronic diseases, WHO technical report series, vol. 916. 2003. p. 1–60.

Lobstein T, Baur L, Uauy R. Obesity in children and young people: a crisis in public health. Obes Rev. 2004;5(s1):4–85.

Swinburn BA et al. Obesity 1: the global obesity pandemic: shaped by global drivers and local environments. Lancet. 2011;378(9793):804–14.

Monteiro CA et al. Ultra-processed products are becoming dominant in the global food system. Obes Rev. 2013;14:21–8.

Kit BK et al. Trends in sugar-sweetened beverage consumption among youth and adults in the United States: 1999–2010. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;98(1):180–8.

Australian Bureau of Statistics, Australian Health Survey: Nutrition first results—foods and nutrients, 2011-2012. Canberra; 2014.

Allman-Farinelli MA et al. Age, period and birth cohort effects on prevalence of overweight and obesity in Australian adults from 1990 to 2000. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2007;62(7):898–907.

van den Berg SW et al. Quantification of the energy gap in young overweight children. The PIAMA birth cohort study. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):326.

Plachta-Danielzik S et al. Energy gain and energy gap in normal-weight children: longitudinal data of the KOPS. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2008;16(4):777–83.

Hoek J, Gendall P. Advertising and obesity: a behavioral perspective. J Health Commun. 2006;11(4):409–23.

Schwartz MB, Kunkel D, DeLucia S. Food marketing to youth: pervasive, powerful, and pernicious. Commun Res Trends. 2013;32(2):4–13.

Boswell RG, Kober H. Food cue reactivity and craving predict eating and weight gain: a meta-analytic review. Obes Rev. 2016;17(2):159–77. Systematic review (all years - 2014): 45 experimental studies which examined effects of food cue reactivity and craving on eating and weight-related outcomes.

Boyland EJ et al. Advertising as a cue to consume: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of acute exposure to unhealthy food and nonalcoholic beverage advertising on intake in children and adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2016;103(2):519–33. Systematic review and meta-analysis (all years - 2014): experimental studies where advertising exposure (television or Internet) was experimentally manipulated, and food intake was measured (16 in children).

Chapman K et al. Fat chance for Mr Vegie TV ads. Aust N Z J Public Health. 2007;31(2):190.

Powell LM, Harris JL, Fox T. Food marketing expenditures aimed at youth: putting the numbers in context. Am J Prev Med. 2013;45(4):453–61.

Zuppa JA, Morton HN, Mehta KP. Television food advertising: counterproductive to children’s health? A content analysis using the Australian Guide to Healthy Eating. Nutr Diet. 2003;60(2):78–84.

Kelly B et al. Television food advertising to children: the extent and nature of exposure. Public Health Nutr. 2007;10(11):1234–40.

Powell LM et al. Nutritional content of television food advertisements seen by children and adolescents in the United States. Pediatr. 2007;120(3):576–83.

Watson WL et al. Determining the ‘healthiness’ of foods marketed to children on television using the Food Standards Australia New Zealand nutrient profiling criteria. Nutr Diet. 2014;71(3):178–83.

Australian Government. Taking preventative action. A response to Australia: the healthiest country by 2020, The report of the National Preventative Health Taskforce. 2010.

World Health Organization. Set of recommendations on the marketing of foods and non-alcoholic beverages to children. 2010.

World Health Organization. Scaling up action against noncommunicable diseases: how much will it cost? 2011.

World Cancer Research Fund International. World Cancer Research Fund International Nourishing Framework: restrict food advertising and other forms of commercial promotion. 2016.

Australian Association of National Advertisers. Submission to the Australian and Media Authority on the Children’s Television Standards Review. 2007.

Moodie R et al. Profits and pandemics: prevention of harmful effects of tobacco, alcohol, and ultra-processed food and drink industries. Lancet. 2013;381(9867):670–9.

Smits T, V.H., Neyens E, Boyland E., The persuasiveness of child-targeted endorsement strategies: a systematic review., in Communication Yearbook, E.L. Cohen, Editor. Routledge; 2015. p. 311-338. Systematic review (2005–2014): reviewed 15 experimental studies which measured the effect that endorsers (promotional/celebrity characters) have on attitudes and food behaviours in children.

Kraak VI, Story M. Influence of food companies’ brand mascots and entertainment companies’ cartoon media characters on children’s diet and health: a systematic review and research needs. Obes Rev. 2015;16(2):107–26. Systematic review (2000–2014): reviewed 11 experimental studies measuring influence of brand characters on food behaviours.

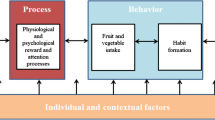

Kelly B et al. A hierarchy of unhealthy food promotion effects: identifying methodological approaches and knowledge gaps. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(4):E86–95. Narrative review: authors developed a hierarchy of effects framework and logic model outlining the behavioural stages that link exposure to food promotion with children’s weight.

Boyland EJ, Whalen R. Food advertising to children and its effects on diet: a review of recent prevalence and impact data. Pediatr Diabetes. 2015;16(5):331–7.

Cairns G, Angus K, Hastings G. The extent, nature and effects of food promotion to children: a review of the evidence to December 2008. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009.

Institute of Medicine, Food marketing to children and youth: threat or opportunity? Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2006.

Hastings, G, et al. The extent, nature and effects of food promotion to children: a review of the evidence. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2006.

Hoek J. Marketing communications and obesity: a view from the dark side. N Z Med J (Online). 2005;118(1220):U1608.

Australian Communications and Media Authority. Review of the Children’s Television Standards 2005 Final Report of the Review. 2009.

Coalition on Food Advertising to Children. Children’s health or corporate wealth? The case for banning television food advertising to children. 2006.

Wakeford R. Association and causation in epidemiology—half a century since the publication of Bradford Hill’s interpretational guidance. J R Soc Med. 2015;108(1):4–6.

Livingstone S. Assessing the research base for the policy debate over the effects of food advertising to children. Int J Advert. 2005;24(3):273–96.

Bradford Hill A. The environment and disease: association or causation? Proc R Soc Med. 1965;58(5):295.

Lucas RM, McMichael AJ. Association or causation: evaluating links between “environment and disease”. Bull World Health Org. 2005;83(10):792–5.

Bosch FX et al. The causal relation between human papillomavirus and cervical cancer. J Clin Pathol. 2002;55(4):244–65.

Gazdar AF, Butel JS, Carbone M. SV40 and human tumours: myth, association or causality? Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2(12):957–64.

Hu FB. Resolved: there is sufficient scientific evidence that decreasing sugar-sweetened beverage consumption will reduce the prevalence of obesity and obesity-related diseases. Obes Rev. 2013;14(8):606–19.

Weyland PG, Grant WB, Howie-Esquivel J. Does sufficient evidence exist to support a causal association between vitamin D status and cardiovascular disease risk? An assessment using Hill’s criteria for causality. Nutrients. 2014;6(9):3403–30.

Olafsdottir S et al. Young children’s screen habits are associated with consumption of sweetened beverages independently of parental norms. Int J Public Health. 2014;59(1):67–75.

Kelly B et al. Television advertising, not viewing, is associated with negative dietary patterns in children. Pediatr Obes. 2016;11(2):158–60.

Giese H et al. Exploring the association between television advertising of healthy and unhealthy foods, self-control, and food intake in three European countries. Appl Psychol: Health and Well-Being. 2015;7(1):41–62.

Scully M et al. Association between food marketing exposure and adolescents’ food choices and eating behaviors. Appetite. 2012;58(1):1–5.

Andreyeva T, Kelly IR, Harris JL. Exposure to food advertising on television: associations with children’s fast food and soft drink consumption and obesity. Econ Hum Biol. 2011;9(3):221–33.

Longacre MR et al. A toy story: association between young children’s knowledge of fast food toy premiums and their fast food consumption. Appetite. 2016;96:473–80.

Ferguson CJ. An effect size primer: a guide for clinicians and researchers. Prof Psychol: Res and Pract. 2009;40(5):532.

Kelly B et al. New media but same old tricks: food marketing to children in the digital age, Current Obesity Reports. 2015. p. 1–9.

Livingstone MBE, Robson PJ, Wallace JMW. Issues in dietary intake assessment of children and adolescents. Br J Nutr. 2004;92(S2):S213–22.

Heath R, Nairn A. Measuring affective advertising: implications of low attention processing on recall. J Advert Res. 2005;45(02):269–81.

Uribe R, Fuentes-García A. The effects of TV unhealthy food brand placement on children. Its separate and joint effect with advertising. Appetite. 2015;91:165–72.

Boyland EJ et al. Food commercials increase preference for energy-dense foods, particularly in children who watch more television. Pediatrics. 2011;128(1):e93–e100.

Dhar T, Baylis K. Fast-food consumption and the ban on advertising targeting children: the Quebec experience. J Mark Res (JMR). 2011;48(5):799–813.

Dovey TM et al. Responsiveness to healthy television (TV) food advertisements/commercials is only evident in children under the age of seven with low food neophobia. Appetite. 2011;56(2):440–6.

Anschutz DJ, Engels RC, Van Strien T. Maternal encouragement to be thin moderates the effect of commercials on children’s snack food intake. Appetite. 2010;55(1):117–23.

Anschutz DJ, Engels RC, Van Strien T. Side effects of television food commercials on concurrent nonadvertised sweet snack food intakes in young children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009;89(5):1328–33.

Harris JL, Bargh JA, Brownell KD. Priming effects of television food advertising on eating behavior. Health Psychol. 2009;28(4):404–13.

Halford JC et al. Beyond-brand effect of television food advertisements on food choice in children: the effects of weight status. Public Health Nutr. 2008;11(9):897–904.

Halford JC et al. Beyond-brand effect of television (TV) food advertisements/commercials on caloric intake and food choice of 5-7-year-old children. Appetite. 2007;49(1):263–7.

Halford JC et al. Effect of television advertisements for foods on food consumption in children. Appetite. 2004;42(2):221–5.

Gorn GJ, Goldberg ME. Behavioral evidence of the effects of televised food messages on children. J Consum Res. 1982;9(2):200–5.

Folkvord F et al. The effect of playing advergames that promote energy-dense snacks or fruit on actual food intake among children. Am J Clin Nutr. 2013;97(2):239–45.

Folkvord F et al. Impulsivity, “advergames,” and food intake. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6):1007–12.

Folkvord F et al. The role of attentional bias in the effect of food advertising on actual food intake among children. Appetite. 2015;84:251–8.

Harris JL et al. US food company branded advergames on the Internet: children’s exposure and effects on snack consumption. J Child Media. 2012;6(1):51–68.

Matthes J, Naderer B. Children’s consumption behavior in response to food product placements in movies. J Consum Behav. 2015;14(2):127–36.

Auty S, Lewis C. Exploring children’s choice: the reminder effect of product placement. Psychol Mark. 2004;21(9):697–713.

Dixon H et al. Effects of nutrient content claims, sports celebrity endorsements and premium offers on pre-adolescent children’s food preferences: experimental research. Pediatr Obes. 2014;9(2):e47–57.

Elliott CD, Elliott CD, Carruthers Den Hoed R, Conlon MJ. Food branding and young children’s taste preferences. A Reassessment. 2013;104(5):5.

Boyland EJ et al. Food choice and overconsumption: effect of a premium sports celebrity endorser. J Pediatr. 2013;163(2):339–43.

McAlister AR, Cornwell TB. Collectible toys as marketing tools: understanding preschool children’s responses to foods paired with premiums. J Public Policy Mark. 2012;31(2):195–205.

Hobin EP et al. The happy meal(R) effect: the impact of toy premiums on healthy eating among children in Ontario, Canada. Can J Public Health. 2012;103(4):e244–8.

Robinson TN et al. Effects of fast food branding on young children’s taste preferences. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2007;161(8):792–7.

Boyland EJ, Kavanagh-Safran M, Halford JCG. Exposure to ‘healthy’ fast food meal bundles in television advertisements promotes liking for fast food but not healthier choices in children. Br J Nutr. 2015;113(06):1012–8.

Ng SH et al. Reading the mind of children in response to food advertising: a cross-sectional study of Malaysian schoolchildren’s attitudes towards food and beverages advertising on television. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:1047.

Lioutas ED, Tzimitra-Kalogianni I. ‘I saw Santa drinking soda!’ Advertising and children’s food preferences. Child Care Health Dev. 2015;41(3):424–33.

Tarabashkina L, Quester P, Crouch R. Food advertising, children/’s food choices and obesity: interplay of cognitive defences and product evaluation: an experimental study. Int J Obes. 2015;40(4):581–6.

Lee B et al. Effects of exposure to television advertising for energy-dense/nutrient-poor food on children’s food intake and obesity in South Korea. Appetite. 2014;81:305–11.

Gregori D et al. Investigating the obesogenic effects of marketing snacks with toys: an experimental study in Latin America. Nutr J. 2013;12:95.

Gregori D et al. Food packaged with toys: an investigation on potential obesogenic effects in Indian children. Indian J Pediatr. 2014;81:30–8.

Ventura AK, Worobey J. Early influences on the development of food preferences. Curr Biol. 2013;23(9):R401–8.

Mennella JA. Ontogeny of taste preferences: basic biology and implications for health. Am J Clin Nutr. 2014;99(3):704S–11S.

Schulte EM et al. Current considerations regarding food addiction. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(4):563.

Harris JL, Graff SK. Protecting young people from junk food advertising: implications of psychological research for First Amendment law. Am J Public Health. 2012;102(2):214–22.

Bargh JA, Ferguson MJ. Beyond behaviorism: on the automaticity of higher mental processes. Psychol Bull. 2000;126(6):925.

Strack F, Deutsch R. Reflective and impulsive determinants of social behavior. Pers Soc Psychol Rev. 2004;8(3):220–47.

Chartrand TL. The role of conscious awareness in consumer behavior. J Consum Psychol. 2005;15(3):203–10.

Nairn A, Fine C. Who’s messing with my mind? The implications of dual-process models for the ethics of advertising to children. Int J Advert. 2008;27(3):447–70.

Buijzen M, Van Reijmersdal EA, Owen LH. Introducing the PCMC model: an investigative framework for young people’s processing of commercialized media content. Commun Theory. 2010;20(4):427–50.

Jansen A. A learning model of binge eating: cue reactivity and cue exposure. Behav Res Ther. 1998;36(3):257–72.

Carter BL, Tiffany ST. Meta-analysis of cue-reactivity in addiction research. Addiction. 1999;94(3):327–40.

Gearhardt AN et al. Relation of obesity to neural activation in response to food commercials. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2014;9(7):932–8.

Bruce AS et al. Brain responses to food logos in obese and healthy weight children. J Pediatr. 2013;162(4):759–764.e2.

Bruce AS et al. Branding and a child’s brain: an fMRI study of neural responses to logos. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2012;9(1):118–22.

Vandenbroeck P, Goosens J, Clemens M. Tackling obesities: future choices—building the obesity system map. London: Government Office for Science; 2007.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

Jennifer Norman declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Bridget Kelly declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Emma Boyland declares that she has no conflict of interest.

Anne-T McMahon has received financial support through grants from the Australian Meals on Wheels Association and the University of Wollongong and has received compensation from Pork CRC, Proportion Foods, Flagstaff Fine Foods, and IRT for conducting qualitative research studies, and from Yum! Corporation for service as a consultant in the development of a Nutrition Advisory Board.

Human and Animal Rights and Informed Consent

This review contains some studies with human subjects performed by Dr Kelly and Dr Boyland. There are no animal studies included in this article.

Additional information

This article is part of the Topical Collection on Cardiovascular Disease

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Norman, J., Kelly, B., Boyland, E. et al. The Impact of Marketing and Advertising on Food Behaviours: Evaluating the Evidence for a Causal Relationship. Curr Nutr Rep 5, 139–149 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-016-0166-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13668-016-0166-6