Abstract

Key message

Spatial analysis could improve the accuracy of genetic analyses, as well as increasing the accuracy of predicting breeding values and genetic gain for Norway spruce trials.

Context

Spatial analysis has been increasingly used in genetic evaluation of field trials in tree species. However, the efficiency of spatial analysis relative to the analysis using the conventional experimental designs or pre- and post-blocking method in Swedish genetic trials has not been systematically evaluated.

Aims

This study aims to examine the effectiveness of spatial analysis in improving the accuracy of predicting breeding values and genetic gain.

Methods

Spatial analysis, using separable first-order autoregressive processes of residuals in rows and columns, was used in nine types of trait classes from 145 field trials of Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) Karst.) in Sweden.

Results

Ninety-six percent of variables (traits) were converged for the spatial model. Large trials with a large block variance tend to have a larger improvement from the model of experimental design to spatial model in accuracy. Growth and Pilodyn measurement traits showed greater improvements in log likelihood, accuracy, and genetic gain. Block variance was reduced by more than 80% for trait height and diameter using spatial analysis, indicating that it is more effective using both pre-blocking and post-blocking analyses in Swedish Norway spruce trials. The prediction accuracy for diameter and height for progeny breeding values showed an increase of 3.6 and 3.4%, respectively. The improvement of efficiency for growth traits is also related to the geographical location of test sites, tree age, number of survival trees, and the spacing of the trial.

Conclusion

The spatial analysis approach is more efficient in Swedish Norway spruce trials than the conventional methods using models based on the experimental design.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

It is well known that progeny trials in forest tree breeding programs usually cover large areas due to the large field space needed for individual trees and the large size of the testing population (several dozens to a few hundred families with multiple individuals from each family). The large physical area needed for a progeny trial usually exhibits considerable variation in environmental conditions (Bian et al. 2017; Dutkowski et al. 2006; Chen et al. 2017). To reduce such environmental heterogeneity, an experimental design subdividing the trial into blocks is usually used (Williams et al. 2002). Randomized complete block (RCB) is by far the most common experimental design, where a site is divided into several blocks (replications) to separate environmental (block) variation from genetic variation (White et al. 2007). To make the comparison of genetic entries more precise and increase the accuracy of estimated genetic parameters and predicted breeding values, RCB is further advanced into a new set of design called balanced incomplete block (BIB) which includes randomized incomplete block (RIB). This achieves a reduction in the overall residual error by further removal of environmental error associated with row and/or column directions and among smaller incomplete blocks. Row/column design and other Latinized square (LS) designs are among those commonly used BIB design in forest genetic trials (Williams et al. 2002). While various blocking methods used for forest genetic trials may be effective in reducing global (trend) variation, spatial analysis was introduced, initially for crops and recently for trees, to account for both global and local microsite variations and therefore further improve the accuracy of breeding value prediction (Cullis et al. 1998; Ye and Jayawickrama 2008). Even with traditional RCB design, implementation of spatial analysis could still improve the model by detecting microsite variations within or between block variations, covering the type of changes in soil depth and nutrition that exist in most trials (Dutkowski et al. 2006; Ye and Jayawickrama 2008).

Spatial analysis can capture both local gradient variations within blocks (patches) and a global gradient trend along the row and column of the trial, so it is becoming a popular method to use for both agricultural and forestry field trials (Anekonda and Libby 1996; Brownie and Gumpertz 1997; Cullis et al. 1998; Cullis and Gleeson 1989; Cullis and Gleeson 1991; Fox et al. 2007a, b; Gilmour et al. 1997; Qiao et al. 2000; Yang et al. 2004; Ye and Jayawickrama 2008; Chen et al. 2017). In forestry, there are several spatial analysis methods used, such as post-blocking (Dutkowski et al. 2002; Ericsson 1997), nearest-neighbor adjustment (Anekonda and Libby 1996; Joyce et al. 2002; Wright 1978), and kriging (Hamann et al. 2002; Zas 2006). However, the most common method used in crop and forestry trials seems to be a combination of experimental design with a spatial component, in the form of separable first-order two-dimensional autoregressive residual variation as recommended by Gilmour et al. (1997).

In the Swedish Norway spruce (Picea abies (L.) Karst.) breeding programs, some progeny trials are very large with more than 1000 families tested, including provenance (stand) and family structures (Chen et al. 2014). Also, many of these trials have used completely randomized design (CRD) without designed pre-block in northern Sweden. Such a design was traditionally analyzed using post-blocking adjustment (PBA) with varying effectiveness (Dutkowski et al. 2002; Ericsson 1997). Spatial analysis may improve breeding value prediction considerably by reducing environmental variation in the CRD field trials.

Recently, the competition effect between neighboring trees has been described in several papers (Cappa and Cantet 2008; Cappa et al. 2015, 2016; Costa e Silva and Kerr 2013; Costa e Silva et al. 2013; Dutkowski et al. 2002; Dutkowski et al. 2006; Ye and Jayawickrama 2008). Dutkowski et al. (2006) reported that 10% of diameter variables showed competition effects, represented by negative first-order autocorrelation coefficients in both column and row directions at a residual level. Ye and Jayawickrama (2008) reported that eight negative autocorrelations from a total of 1135 variables were observed, either in one direction or in both directions of row and column. Stringer and Cullis (2002) found that inter-plot competition was substantial in many field trials measuring sugar cane yield. In Sweden, most field trials were located north of 56° latitude in the northern hemisphere and trees were usually measured before the age of 20. Competition might appear in some trials. Therefore, examination of whether competition has played a role at this age using a spatial model with first-order autocorrelation coefficients in row and column directions is meaningful.

The objectives of this study were to (1) examine the degree and severity of spatial variation in genetic field trials of Norway spruce in Sweden; (2) estimate the average changes for several variance components, and the accuracy of parental and offspring breeding value predictions, from the base design to the spatial model; (3) investigate the influence of different spacing, age, and geographical factors on the estimates of variance components; and (4) examine whether competition effect is existing in growth traits based on the first-order autoregressive coefficients in the row and column directions.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Test materials

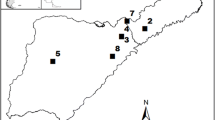

The data from a total of 145 field trials of Norway spruce distributed across Sweden were analyzed (Fig. 1). Most of these trials were located in southern Sweden, with only 16 and 11 trials from central and northern Sweden, respectively. Eighty-six trials were family-based seedlings (including full-sib, half-sib, and mixed) while 59 trials were clonal-based experiments.

Four base designs (CRD, RCB, RIB, and LS) were used in these field trials. Most of the family-based trials used single-tree plots, predominantly in a randomized incomplete block design (see supplementary Table S1). Most of the clonal trials used a Latin square design with a pre-blocking structure. Post-blocks are usually added when using a CRD design, which means that blocks are added in response to environmental differences observed in the field for the trials with an initial CRD design. There were 11 types of spacing, but in most of the trials, spacings were 1.4 m × 1.4 m (88 trials), 1.8 m × 1.8 m (8 trials), and 2 m × 2 m (28 trials). A total of 454 unique variables representing nine trait classes were measured and analyzed (Table 1). The nine trait classes were as follows: branch—representing seven branch characteristics from number of branches and branch diameter, to number of spike knots; diameter—stem diameter at breast height (1.3 m above ground); form—stem straightness; frost—frost damage; insect—insect damage; height—tree height; stems—number of multiple stems; bud burst—bud burst stage (Krutzsch 1975); and wood density—Pilodyn penetration. The number of variables and measurement ages varied among these trait classes in the 145 trials (Table 1). The details of each field trial including field design, family, and clone number are shown in the supplementary Table S1.

2.2 Statistical analysis

Two models were used to fit each of 454 variables:

-

(1)

A base model that only included a random block effect (pre-block or post-block), a random genetic effect, and an independent error as

where y is a vector of measured data, b is a vector of fixed effects of the grand mean with its design matrix X, u is a vector of random effects with block and genetics (additive or genotype effect) corresponding design matrix Z, and e is a vector of residuals. Fixed and random effect solutions are obtained by solving the linear mixed model equations:

where R is the variance-covariance matrix of the residuals and G is the direct sum of the variance-covariance matrices of each of the random effects. Residuals are assumed to be independent and R is denoted as \( {\sigma}_e^2\mathbf{I} \) in the base model.

-

(2)

A spatial model using an autoregressive spatial component and an independent error instead of just an independent error in base model (Costa e Silva et al. 2001; Dutkowski et al. 2002) as

where spatially dependent (ξ) residual and independent (η) residual (nugget effect) are a decomposition of e in base model. Other parts are all the same as the base model.

The spatially dependent (ξ) residuals are modeled using a covariance structure that assumes a separable first-order autoregressive process in rows and columns, for which the R matrix is

where \( {\sigma}_{\xi}^2 \) is the spatially dependent residual variance, \( {\sigma}_{\eta}^2 \) is the independent residual variance, I is an identity matrix, ⊗ is a direct product (the Kronecker product) for two matrices, and AR1(pcol) and AR1(prow) represent a first-order autoregressive correlation matrix in column and row directions, respectively.

For field trials of open-pollinated and control-pollinated families, and for clonal trials using family structure, only the additive variance component was calculated in the model. For clonal trials without parental pedigree, genotypic values were predicted. The missing values were fitted as fixed effects in the spatial model.

To carry out the log likelihood ratio test (LRT) in ASReml 3.0, all the traits were analyzed using untransformed data. For categorical variables, the previous comparison between untransformed and transformed data indicated that the ranking did not normally change significantly (Rosvall et al. 2011), so other transformations were not tried for those variables. Variables recorded as counts were not transformed as it was observed that transformation using the square root for counts did not further normalize the distribution (Dutkowski et al. 2006).

During the model fitting process, we found that some variables had a non-significant nugget effect in the spatial model, which is similar to some experiments on agricultural crops. With this type of variables, Gilmour et al. (1997) recommended that extraneous effects should be fitted as

where b is a vector of fixed effects with the grand mean, linear row, linear column, and edge effect corresponding design matrix X and u is a vector of random effects with block, spline row, spline column, row, column, and genetics (additive or genotype effect) corresponding design matrix Z. ξ is the spatially dependent residuals. If spline across rows and columns did not fit the model, polynomial function across rows and columns was employed to account for the global trend. The variogram and map of residuals for spatial model were used to indicate such trends.

2.3 Variance parameters and model comparison

The variance parameters were estimated using restricted (or reduced or residual) maximum likelihood (REML) in ASReml 3.0 (Gilmour et al. 2009). Standard errors were estimated by using the Taylor series expansion method. To study the effectiveness of using a spatial model relative to model without spatial effect, only block and additive effects, regardless of their significance, were always included in the final model and in the extended model, all other non-significant variance parameters (such as random column and row effects) were removed from the fitted models, except the block and additive effects. The significance of a given parameter was judged using a one-tailed LRT for those where zero was a boundary value; otherwise, a two-tailed test was used. When spatial component was used in R, in some cases, it did not converge readily. Then a few of strategies were tried to achieve convergence: (1) Update function was used to update several times in ASReml-R, (2) lower starting autocorrelations were tried, and (3) spatial component was incorporated into a random effect.

The accuracy of the predicted breeding values (correlation between the true and predicted genetic values) was calculated for each parent and offspring or genotypic effects of clones as

where PEV is the prediction error variance and \( {\widehat{\sigma}}_a^2 \) is the estimated additive genetic variance. If it was a clonal trial, \( {\widehat{\sigma}}_a^2 \) was the estimated genotypic variance.

The relative genetic gain was estimated as 100 ∗ (GS − GB)/GB, where GS and GB are the expected genetic response from selecting a proportion of individuals using the spatial and base models, respectively (Costa e Silva et al. 2001). The selection proportion was set at the top 20% for parents and top 5% for offspring or genotypic values, based on estimated breeding values or clonal genotypic values. GS and GBwere calculated as an average of breeding or clonal genotypic values. Spearman correlation was calculated to compare the breeding values between the base and spatial models.

3 Results

The spatial models converged for 434 variables from a total of 454 variables examined in the 145 trials. The remaining non-converged 20 variables were excluded from the following analysis.

A total of 381 variables (88%) were observed to have a significant improvement of log likelihood between the base and spatial models (Table 2). Growth and wood density (Pilodyn penetration) traits had the greatest improvement with 97.7% of trait diameter, 99.4% of trait height, and 100% of trait wood. Multiple stems, insect damage, and branch had the least improvement using spatial models. Bud burst, stem straightness, and frost resistance showed moderate improvement using spatial models.

In large trials (n > 2500 trees), there were more variables with a higher ratio of block to error variance (Table 3). For example, the ratios of block to error variances of 0–10, 10–20, 20–30, 30–40, 40–50, and 50–100% accounted for 50.0, 25.8, 9.2, 8.3, 3.3, and 3.3% of variables, respectively. For small trials (n < 2500 trees), the ratios of block to error variances of 0–10, 10–20, 20–30, 30–40, 40–50, and 50–100% accounted for 68.2, 14.0, 8.3, 3.2, 2.5, and 3.8% of variables, respectively. Large trials where block variance explained much of the variation tended to show a greater improvement in log likelihood (Table 3). For example, for ratio of block to error variances of 10–20%, all sites with n > 2500 trees had a log likelihood improvement at p < 10−7, while only 68% sites in sites with n < 2500 trees had a log likelihood improvement at p < 10−7, with the other 32% of sites having a log likelihood improvement distributed from p ≥ 0.5 to p < 10−6.

Average changes of estimated variance components when switching from the base to the spatial model are shown in Table 4, excluding variables with no significant improvement using the spatial model. Here, we only describe overall results for the variables showing significant improvement.

Generally, spatial analysis reduced all average block variances (\( \Delta {\sigma}_B^2 \)) for all nine types of trait classes, but the reduction varied substantially from 45.0% for trait bud burst to 86.1% for trait diameter with an average reduction of 66.2%. Spatial analysis reduced the block variance more than 79.0% for diameter, height, and multiple stems traits. For example, the block variance (\( {\sigma}_B^2 \)) of trait diameter decreased from 13.4 to 2.2%. For branch, diameter, frost, and height traits, however, block variances increased slightly in a few cases. For example, 3.1% of branch variables and 4.8% of frost variables had an increase in block variances (Table 4).

Average changes in the estimated additive genetic variance (\( \Delta {\sigma}_A^2 \)) also varied for the nine types of trait classes. The \( \Delta {\sigma}_A^2 \) increased slightly for branch, diameter, form, height, and wood density, but decreased for frost damage, multiple stems, and bud burst. With the exception of wood density and frost damage traits, all other traits had more than 50% of variables that increased \( {\sigma}_A^2 \) from the base model to the spatial model.

Spatial analysis reduced the independence variance (\( {\sigma}_{\boldsymbol{\eta}}^2 \)) for all variables of nine types of traits. The average reduction of \( \Delta {\sigma}_{\boldsymbol{\eta}}^2 \) was 17.9% and this varied from an average reduction of 7.1% for bud burst to 33.3% for insect damage. Dependence variances (\( {\sigma}_{\boldsymbol{\xi}}^2 \)) for nine types of trait classes varied from an average of 8.5% for insect to 77.7% for diameter.

Spatial correlations were high for most variables examined (Table 5). The average autocorrelation coefficient for column (Pc) and row (Pr) was 0.76 and 0.79, respectively. Autocorrelation coefficients for trait diameter, height, and wood density were higher with the values above 0.80 for row and column. Only three variables had autocorrelation coefficients of less than 0.5 (− 0.16, 0.19, and 0.31) in one direction for diameter at age 13, 16, and 20 years, respectively. And three variables had autocorrelation of less than 0.5 (− 0.04, 0.43, and 0.45) in one direct for height at age 7, 3, and 8, respectively. There was no variable with negative value for wood density.

The average accuracy of breeding value predictions (∆A) for parents increased for six types of trait classes (branch, diameter, form, insect, height, and wood density) but decreased for frost damage, multiple stems, and bud burst (Table 5). However, these changes were small with the largest increases being for insect damage, diameter, and height (5.0, 1.8, and 1.7%, respectively). The accuracy of breeding value predictions for diameter, height, and wood density was increased in 86.9, 74.0, and 75.0% of cases, respectively, from the base to spatial models. Similarly, the accuracy of breeding value predictions for offspring was also increased most for diameter (95.2% with an average 3.6%) and height (81.9% with an average 3.4%) from the base of the spatial models.

In Table 5, the Spearman correlation coefficients of parents (PC) and offspring (OC) between the predicted breeding values for the base model and spatial model were all higher (> 0.93, except for a correlation coefficient of 0.89 for wood density).

The average increase of the estimated genetic gain for parents (P_GG) varied from 0 to 6.2% for different trait classes (Table 5) while the average changes of the estimated genetic gain for offspring (O_GG) varied from 0.4 to 4.2%. Diameter, height, and wood density showed the highest gain increases from the base to spatial model (1.9, 4.3, and 6.2% for parents, respectively, and 3.6, 4.2, and 3.7% for offspring, respectively).

We used Pearson correlation analysis to examine the effect of tree age, site location, number of survival trees, and spacing on the improvement using the spatial model (Table 6). For diameter, we found that the effectiveness of spatial analyses increased with increased site elevation, latitude, longitude, number of survival trees, and spacing, particularly for latitude. This meant that the accuracy of offspring diameter breeding value predictions increased more using spatial analyses for more northerly sites (higher latitude) with a greater reduction in independent residual variance. For height, there seems to be little relationship between accuracy and geographical parameters and other parameters, except for tree age, in that accuracy increased significantly with age. Autocorrelation coefficients in row and column directions also increased, following the increase of tree age from 3 to 16 years.

Nine variables showed non-significant nugget effects in this study. Five of them were height variables, two were branching variables, and there was one each for diameter and frost damage. For the two branch angle variables, the pattern of the spatial residuals approached randomness (Fig. 2). No extraneous effects were found in these two variables. For the other seven variables, extended models were fitted and were significant. Correlation coefficients of breeding values between the spatial and extended models were all higher than 0.98 for the seven variables. No substantial genetic gain was observed from the spatial model to the extended spatial model for the seven variables (Table 7). Therefore, adding the significant extraneous effects using the extended model did not produce an improvement for the genetic gain: the largest parental gain was 0.07 for the height and the largest offspring gain was still only 0.21 for height (Table 7). One example of effectiveness using the extended spatial model is illustrated in Fig. 3. The variogram for diameter showed a raised edge in the last row and some variation in column direction, indicating trees in the last row in the row direction, may grow abnormally (faster than other neighboring trees) and there may be a slight global trend in column direction. When an edge effect in the last row and a spline in the column direction were fitted, a more stationary variogram was produced.

4 Discussion

Spatial analysis using first-order autocorrelation has been used as a common method to analyze forest genetic trials (Costa e Silva et al. 2001; Costa e Silva and Kerr 2013; Dutkowski et al. 2006, 2002; Ye and Jayawickrama 2008). In Norway spruce, we have used spatial analyses as a first-stage analyses for individual sites, and adjusted data have been used for genotype-by-site (G×E) interaction study to dissect the patterns and causes of significant G×E (Chen et al. 2017). Here, we summarized genetic parameters, autocorrelation coefficients, accuracy of breeding value predictions for parental and offspring, and genetic gain for nine types of trait classes from base and spatial models in this study of Norway spruce in Sweden.

Spatial analyses of Norway spruce showed that 88% of variables (from a total of 434) could be significantly improved for model fitting using a spatial model based on LRT. Growth and wood density (Pilodyn penetration) traits were observed to have a greater probability of improvement than other traits. This may indirectly indicate that spatial analyses could greatly improve genetic analyses of wood density measured using the Pilodyn method (Chen et al. 2015). Spatial autocorrelation coefficients for the growth traits and wood density were higher than those for other traits. This could be explained by the high sensitivity of growth and wood density to site variation including microsite soil depth, nutrition, slope, and water availability. This indicates spatial analysis is more desirable for analyzing growth and Pilodyn penetration traits.

Our results also indicate that spatial analysis could have a greater impact on large trials with highly global heterogeneous (higher ratio of block to residual variances) environmental variation, confirming previous reports in a few published papers (Dutkowski et al. 2006; Fu et al. 1999; Ye and Jayawickrama 2008).

Experimental design factors that were found significant are usually recommended to be retained in the spatial model (Dutkowski et al. 2002, 2006; Federer 1998; Qiao et al. 2000; Ye and Jayawickrama 2008). In most of the northern Swedish Norway spruce trials, a simple experimental CRD was usually used in the field experiments, and all trees were usually randomized in the field trials. In those trials, post-blocking was used to reduce environmental variation in the analyses. In two published papers (Dutkowski et al. 2002; Ericsson 1997), the post-blocks had equal size, but in Swedish trials, those post-blocks within a trial could be of different sizes (e.g., one block may include four sub-blocks and another block may include six sub-blocks, depending on the environmental similarity). This post-blocking strategy might confound block and genetic effects. A simulation may be needed to resolve this issue. In this study, we found spatial analysis was more efficient in field trials. Thus, post-blocking and pre-blocking may not need for the future analyses of field data.

Spatial analysis showed an inconsistent effect on the additive genetic variance (\( {\sigma}_A^2 \)). Several studies with only one trial or a few variables and simulations have shown that a consistent increase of \( {\sigma}_A^2 \) is possible with spatial analyses (Anekonda and Libby 1996; Ball et al. 1993; Hamann et al. 2002; Kusnandar and Galwey 2000; Magnussen 1993, 1994). However, experimental studies with large number of trials and variables have shown that either an increase or decrease is possible for \( {\sigma}_A^2 \) using spatial analyses. Our observations of increased additive variance in most cases and decreased variance in some cases are in line with those reports with many trials and variables (Costa e Silva et al. 2001; Dutkowski et al. 2002, 2006; Ye and Jayawickrama 2008). There may several possibilities with decreased genetic variance in spatial model. One possibility is confounding of incomplete block effect with genetic effect in the designed experiment which had augmented the genetic variance. Other possibility includes ill-fitting of model or confounding of genetic effect with spatial variation. Simulation is needed to verify these hypotheses. Dutkowski et al. (2002) considered that a consistent increase of additive variances in the simulation study may be due to there being no independent error term in the model.

Generally, competition is indicated with a negative autocorrelation coefficient at a residual level and/or a negative genetic correlation between a tree and its neighbors at a genetic level (Costa e Silva and Kerr 2013; Magnussen 1989; Reed and Burkhart 1985). Fox et al. (2001) summarized many published forestry-based competition-related papers (Anekonda and Libby 1996; Kuuluvainen et al. 1996; Magnussen 1994; Magnussen and Yeatman 1987) and confirmed the hypothesis reported by Reed and Burkhart (1985) that pre-canopy closure stands usually exhibit positive spatial dependence. Post-canopy closure sometimes shows a negative spatial dependence which can be caused by the onset of competition. Older, senescent stands tend to show a positive spatial dependence. In this study, only two growth variables showed a small negative autocorrelation coefficient in one direction, which again indicates that the competition effect may not be evident before or during the field assessment period for genetic parameter estimates and selection for the Swedish Norway spruce breeding program (most trials younger than 17 years in this study). Ye and Jayawickrama (2008) considered that it was likely that relatively small but still positive autocorrelations would be observed when strong spatial association and competition co-exist. In this study, we found that six variables had autocorrelation coefficients of less than 0.5 in one direction for diameter and height. It may be worth analyzing the indirect genetic effect using the extended competition model recommended by Costa e Silva et al. (2013).

As most of the southern Swedish Norway spruce trials were used in this study, it made sense to explore the patterns of geography, age, number of survival trees, and spacing on genetic parameters. No strong geographical pattern for genetic parameters was found in our study, as in the report by Ye and Jayawickrama (2008). However, it was found that ∆LL had significantly high correlations with the number of survival trees, latitude, and longitude for diameter and height, indicating that the number of survival trees is an important determinant for spatial modeling besides geographical location. Spacing had a greater influence on ∆LL for diameter, but not for height, indicating that the spatial model is more useful for the diameter trait in the large spaced trial.

In variety trials of agricultural crops where the experimental unit is the plot, an independent error is assumed to represent measurement error. Such error variance is often significant but usually small, so the independent error is removed from the model (Cullis et al. 1998; Gilmour et al. 1997). In most forestry trials, it is considered that both an independent and an autoregressive error are necessary (Costa e Silva et al. 2001; Dutkowski et al. 2002; Kusnandar and Galwey 2000). If the model is fitted without the independent error, the additive genetic variance could be substantially inflated and the actual patterns of spatial variation could be obscured when real independent errors are ignored. We found that the independent error was considerable in most of the variables analyzed in individual-tree models. If only additive variance is included in the spatial model, the large independent error could be a mixture of the non-additive variance, measurement error, and microsite error. In the clonal trials, the independent errors may only reflect the measurement error and microsite variation. In our study, all variables in clonal trials showed significant and substantial independent errors. If we considered the measurement error is under control, then, this reflects a large microsite variation.

We did, however, find that nine variables including the height, diameters, branch angle, and frost had non-significant independent residual errors in the field trials. This is similar to observation of Dutkowski et al. (2006) that, in some instances, there were no independent residual variances in forestry trials. When there is significant independent error, Costa e Silva et al. (2001) and Dutkowski et al. (2002) indicated that separation of global and local trends was unnecessary. In agricultural trials, however, an extended model without a non-significant independent error term is recommended by Gilmour et al. (1997) and others (Cullis and Gleeson 1989; Qiao et al. 2000). Therefore, in this study, the extended model was used to detect the improvement for parental and offspring ranking correlations and selection gain in these nine variables. The results showed that the extended model had very little impact on genetic parameters and genetic gain estimates. Therefore, there might be limited use of the extended spatial model if there is no significant independent error, unless a clear global trend or an extraneous effect is detected.

5 Conclusion

The results from this study indicate that

-

1.

The spatial analysis improved the model fitting, accuracy of breeding valve prediction, and genetic gain in Swedish Norway spruce trials than the conventional methods using models based on the experimental design.

-

2.

Large trials with a large block variance tend to have a larger improvement of accuracy from the spatial model in accuracy.

-

3.

Growth and Pilodyn measurement traits showed greater improvements in accuracy and genetic gain.

References

Anekonda TS, Libby WJ (1996) Effectiveness of nearest-neighbor data adjustment in a clonal test of redwood. Silvae Genet 45:46–51

Ball ST, Mulla DJ, Konzak CF (1993) Spatial heterogeneity affects variety trial interpretation. Crop Sci 33:931–935. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci1993.0011183X003300050011x

Bian L, Zheng R, Su S, Lin H, Xiao H, Wu HX, Shi J (2017) Spatial analysis increases efficiency of progeny testing of Chinese fir. J For Res 28:445–452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11676-016-0341-z

Brownie C, Gumpertz ML (1997) Validity of spatial analyses for large field trials. J Agr Biol Envir St 2:1–23. https://doi.org/10.2307/1400638

Cappa EP, Cantet RJ (2008) Direct and competition additive effects in tree breeding: Bayesian estimation from an individual tree mixed model. Silvae Genet 57:45–55

Cappa EP, Muñoz F, Sanchez L, Cantet RJC (2015) A novel individual-tree mixed model to account for competition and environmental heterogeneity: a Bayesian approach. Tree Genet Genomes 11:120. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11295-015-0917-3

Cappa EP, Stoehr MU, Xie C-Y, Yanchuk AD (2016) Identification and joint modeling of competition effects and environmental heterogeneity in three Douglas-fir (Pseudotsuga menziesii var. menziesii) trials. Tree Genet Genomes 12:102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11295-016-1061-4

Chen Z-Q, García Gil MR, Karlsson B, Lundqvist S-O, Olsson L, Wu HX (2014) Inheritance of growth and solid wood quality traits in a large Norway spruce population tested at two locations in southern Sweden. Tree Genet Genomes 10:1291–1303. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11295-014-0761-x

Chen Z-Q, Karlsson B, Lundqvist S-O, García Gil MR, Olsson L, Wu HX (2015) Estimating solid wood properties using Pilodyn and acoustic velocity on standing trees of Norway spruce. Ann For Sci 72:499–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-015-0458-9

Chen Z-Q, Karlsson B, Wu HX (2017) Patterns of additive genotype-by-environment interaction in tree height of Norway spruce in southern and central Sweden. Tree Genet Genomes 13:25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11295-017-1103-6

Costa e Silva J, Dutkowski GW, Gilmour AR (2001) Analysis of early tree height in forest genetic trials is enhanced by including a spatially correlated residual. Can J For Res 31:1887–1893. https://doi.org/10.1139/x01-123

Costa e Silva J, Kerr RJ (2013) Accounting for competition in genetic analysis, with particular emphasis on forest genetic trials. Tree Genet Genomes 9:1–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11295-012-0521-8

Costa e Silva J, Potts BM, Bijma P, Kerr RJ, Pilbeam DJ (2013) Genetic control of interactions among individuals: contrasting outcomes of indirect genetic effects arising from neighbour disease infection and competition in a forest tree. New Phytol 197:631–641. https://doi.org/10.1111/nph.12035

Cullis B, Gogel B, Verbyla A, Thompson R (1998) Spatial analysis of multi-environment early generation variety trials. Biometrics 54:1–18. https://doi.org/10.2307/2533991

Cullis BR, Gleeson AC (1989) Efficiency of neighbour analysis for replicated variety trials in Australia. J Agric Sci 113:233–239. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021859600086810

Cullis BR, Gleeson AC (1991) Spatial analysis of field experiments-an extension to two dimensions. Biometrics 47:1449–1460. https://doi.org/10.2307/2532398

Dutkowski GW, Costa e Silva J, Gilmour AR, Lopez GA (2002) Spatial analysis methods for forest genetic trials. Can J For Res 32:2201–2214. https://doi.org/10.1139/x02-111

Dutkowski GW, Costa e Silva J, Gilmour AR, Wellendorf H, Aguiar A (2006) Spatial analysis enhances modelling of a wide variety of traits in forest genetic trials. Can J For Res 36:1851–1870. https://doi.org/10.1139/x06-059

Ericsson T (1997) Enhanced heritabilities and best linear unbiased predictors through appropriate blocking of progeny trials. Can J For Res 27:2097–2101. https://doi.org/10.1139/x97-153

Federer WT (1998) Recovery of interblock, intergradient, and intervariety information in incomplete block and lattice rectangle designed experiments. Biometrics 54:471–481. https://doi.org/10.2307/3109756

Fox JC, Ades PK, Bi H (2001) Stochastic structure and individual-tree growth models. Forest Ecol Manag 154:261–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0378-1127(00)00632-0

Fox JC, Bi H, Ades PK (2007a) Spatial dependence and individual-tree growth models: I. Characterising spatial dependence. Forest Ecol Manag 245:10–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2007.04.025

Fox JC, Bi H, Ades PK (2007b) Spatial dependence and individual-tree growth models: II. Modelling spatial dependence. Forest Ecol Manag 245:20–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foreco.2007.01.085

Fu Y-B, Yanchuk AD, Namkoong G (1999) Spatial patterns of tree height variations in a series of Douglas-fir progeny trials: implications for genetic testing. Can J For Res 29:714–723. https://doi.org/10.1139/x99-046

Gilmour AR, Cullis BR, Verbyla AP (1997) Accounting for natural and extraneous variation in the analysis of field experiments. J Agr Biol Envir St 2:269–293. https://doi.org/10.2307/1400446

Gilmour AR, Gogel BJ, Cullis BR, Thompson R (2009) ASReml user guide release 3.0. VSN International Ltd, Hemel Hempstead

Hamann A, Namkoong G, Koshy MP (2002) Improving precision of breeding values by removing spatially autocorrelated variation in forestry field experiments. Silvae Genet 51:210–215

Joyce D, Ford R, Fu YB (2002) Spatial patterns of tree height variations in a black spruce farm-field progeny test and neighbors-adjusted estimations of genetic parameters. Silvae Genet 51:13–18

Krutzsch P (1975) Die Pflanzschulenergebnisse eines inventierenden Fichtenherkunftsversuches, Department of Forest Genetics. Royal College of Forestry, Stockholm

Kusnandar D, Galwey N (2000) A proposed method for estimation of genetic parameters on forest trees without raising progeny: critical evaluation and refinement. Silvae Genet 49:15–20

Kuuluvainen T, Penttinen A, Leinonen K, Nygren M (1996) Statistical opportunities for comparing stand structural heterogeneity in managed and primeval forests: an example from boreal spruce forest in southern Finland. Silva Fennica 30:315–328

Magnussen S (1989) Effects and adjustments of competition bias in progeny trials with single-tree plots. For Sci 35:532–547

Magnussen S (1993) Bias in genetic variance estimates due to spatial autocorrelation. Theor Appl Genet 86:349–355. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf00222101

Magnussen S (1994) A method to adjust simultaneously for spatial microsite and competition effects. Can J For Res 24(5):985–995. https://doi.org/10.1139/x94-129

Magnussen S, Yeatman CW (1987) Adjusting for inter-row competition in a jack pine provenance trial. Silvae Genet 36:206–214

Qiao CG, Basford KE, DeLacy IH, Cooper M (2000) Evaluation of experimental designs and spatial analyses in wheat breeding trials. Theor Appl Genet 100:9–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s001220050002

Reed DD, Burkhart HE (1985) Spatial autocorrelation of individual tree characteristics in loblolly pine stands. For Sci 31:575–587

Rosvall O, Ståhl P, Almqvist C, Anderson B, Berlin M, Ericsson T, Eriksson M, Gregorsson B, Hajek J, Hallander J (2011) Review of the Swedish tree breeding programme. Skogforsk, Uppsala, Sweden

Stringer JK, Cullis BR (2002) Application of spatial analysis techniques to adjust for fertility trends and identify interplot competition in early stage sugarcane selection trials. Aust J Agric Res 53:911–918. https://doi.org/10.1071/AR01151

White TL, Adams WT, Neale DB (2007) Forest genetics. CABI, Wallingford. https://doi.org/10.1079/9781845932855.0000

Williams ER, Matheson AC, Harwood CE (2002) Experimental design and analysis for tree improvement. CSIRO publishing, Canberra, Australia

Wright JW (1978) An analysis method to improve statistical efficiency of a randomized complete block design. Silvae Genet 27:12–14

Yang R-C, Ye TZ, Blade SF, Bandara M (2004) Efficiency of spatial analyses of field pea variety trials. Crop Sci 44:49–55. https://doi.org/10.2135/cropsci2004.4900

Ye TZ, Jayawickrama KJS (2008) Efficiency of using spatial analysis in first-generation coastal Douglas-fir progeny tests in the US Pacific Northwest. Tree Genet Genomes 4:677–692. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11295-008-0142-4

Zas R (2006) Iterative kriging for removing spatial autocorrelation in analysis of forest genetic trials. Tree Genet Genomes 2:177–185. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11295-006-0042-4

Acknowledgements

We greatly appreciate the work carried out by all the people who measured and imported all the data into DATAPLAN.

Funding

This study is partly financed by the Swedish Foundation for Strategic Research (RBP 14-0040) and Formas (230-2014-427).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Handling Editor: Bruno Fady

Contribution of the co-authors

Zhiqiang Chen’s contribution includes field data collection, data analysis, and the writing of the manuscript. Andreas Helmersson, Johan Westin, and Bo Karlsson coordinated field experiment and data collection and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. Harry X. Wu initiated the project, designed analytical strategy, and contributed to the writing of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary Table S1

(DOCX 53 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Chen, Z., Helmersson, A., Westin, J. et al. Efficiency of using spatial analysis for Norway spruce progeny tests in Sweden. Annals of Forest Science 75, 2 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-017-0680-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13595-017-0680-8