Abstract

Key message

Recent growth changes (1980–2007) in Western European forests strongly vary across tree species, and range from +42% in mountain contexts to −17% in Mediterranean contexts. These changes reveal recent climate warming footprint and are structured by species' temperature (−) and precipitation (+) growing conditions.

Context

Unprecedented climate warming impacts forests extensively, questioning the respective roles of climatic habitats and tree species in forest growth responses. National forest inventories ensure a repeated and spatially systematic monitoring of forests and form a unique contributing data source.

Aims

A primary aim of this paper was to estimate recent growth changes in eight major European tree species, in natural contexts ranging from mountain to Mediterranean. A second aim was to explore their association with species’ climatic habitat and contemporary climate change.

Methods

Using >315,000 tree increments measured in >25,000 NFI plots, temporal changes in stand basal area increment (BAI) were modelled. Indicators of climate normals and of recent climatic change were correlated to species BAI changes.

Results

BAI changes spanned from −17 to +42% over 1980–2007 across species. BAI strongly increased for mountain species, showed moderate/no increase for generalist and temperate lowland species and declined for Mediterranean species. BAI changes were greater in colder/wetter contexts than in warmer/drier ones where declines were observed. This suggested a role for climate warming, further found more intense in colder contexts and strongly correlated with species BAI changes.

Conclusion

The predominant role of climate warming and species climatic habitat in recent growth changes is highlighted in Western Europe. Concern is raised for Mediterranean species, showing growth decreases in a warmer climate with stable precipitation.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

There is compelling evidence that forest growth has increased over decades in the Northern hemisphere (Boisvenue and Running 2006; Myneni et al. 1997; Spiecker et al. 1996), as a consequence of anthropogenic atmospheric CO2 increase and nitrogen deposition onto forest ecosystems (Bontemps et al. 2011; Becker 1989; Hari and Arovaara 1988; Kahle et al. 2008; Lamarche et al. 1984; Nellemann and Thomsen 2001). Climate warming is more recent (Jones et al. 2012) and unprecedented in magnitude since the 1980s, coming along with an accumulation of temperature records (Coumou and Rahmstorf 2012). It therefore sets a newer context for forests, with far less evidence accumulated as of its impact on forest growth (Lindner et al. 2014).

Climate warming is also pervasive (Hansen et al. 2006), affecting forests in contrasted climatic habitats where temperature (e.g. in the mountain or boreal ranges, Cienciala et al. 2016; Hellmann et al. 2016) or water (e.g. in in the European Mediterranean area or in temperate lowlands, Kint et al. 2012) may form the primary ecosystem limitations (Babst et al. 2013). Forest growth responses are thus expected to reflect these contextual differences (Lindner et al. 2010), and reportedly range from positive in boreal contexts (Kauppi et al. 2014; Wu et al. 2014) to negative in the Mediterranean area (Jump et al. 2006; Martin-Benito et al. 2008; Piovesan et al. 2008), whereas they show greater variation in less investigated temperate and continental contexts (Bontemps et al. 2012; Gschwantner 2006; Kint et al. 2012). Some studies however conflict these general trends, including the absence of climate warming-induced growth changes in the Alps (Hartl-Meier et al. 2014) and across boreal forests of Eurasia (Hellmann et al. 2016). Climate warming further shows variations at different scales in space (Jones et al. 2012; Vidal et al. 2010) and across topographical contexts (Kotlarski et al. 2012), generating strong local heterogeneity in forest growth responses (Hellmann et al. 2016; Zang et al. 2014).

Across a variety of climate types, forest composition in tree species will unavoidably also change, as tree species occupy distinct climatic habitats and show intrinsic differential responses to temperature or water availability (Niinemets and Valladares 2006; Way and Oren 2010; Zang et al. 2014). Species’ sensitivity to climate change has hence been shown to be predictable from their climatic niches and the intensity of climate change (Thuiller et al. 2005), making their variety a full component of forest growth responses to climate change. When observed in comparable climatic habitats, different tree species accordingly often exhibit contrasted growth reponses (Bontemps et al. 2012; Hellmann et al. 2016; Kint et al. 2012; Zang et al. 2014). Thus, whether tree species climatic habitats form a primary determinant of species responses to climate change (habitat-driven response) or species drive a more versatile set of intrinsic growth responses (taxonomic-driven response) remains an open question. The issue has crucial implications for the potential role of tree species in adapting forests to climate change, but it has still received little consideration to date (but see Babst et al. 2013). Studies comparing growth changes across tree species (e.g. Bontemps et al. 2012; Kint et al. 2012; Vila et al. 2008) also currently remain of restricted regional extent, and call for systematic explorations of tree species growth changes over areas representative of their climatic habitats.

In this context, the National Forest Inventory (NFI) programs that monitor countries’ forests on a larger scale provide a useful data source for such investigations, as their coverage goes far beyond the typical tenths of plots available in long-term experimental networks (Pretzsch et al. 2014; Yue et al. 2014) or in retrospective analyses (Bontemps et al. 2012; Hartl-Meier et al. 2014; Kint et al. 2012). NFI programs have been implemented in most European countries as a primary source of information on forests relying on periodic and spatially systematic sampling principles (Tomppo et al. 2010). Since they provide a typical temporal coverage of up to a several decades, they are of no primary interest to explore the impacts of global environmental changes over the longer term, as is targeted in dendrochronology approaches (Spiecker et al. 1996). This aspect may account for their confidential use in studies of growth changes to date (Bowman et al. 2013). Conversely, they turn of much higher relevance when addressing impacts of recent climatic warming onto forests comes into debate (Charru et al. 2014). Their comprehensive coverage of countries’ forests, with a spatial sampling resolution of typically 1 to 10 km, make them inclusive of the whole range of climatic conditions covered by these forests, and of the different tree species they are composed of. The use of NFI observations is thus a salient feature of the very few studies delivering large-scale and systematic assessments of forest growth changes (Elfving and Tegnhammar 1996 in Sweden; Hasenauer et al. 1999 and Gschwantner 2006 in Austria; an exception is Kahle et al. 2008 using retrospective data). Historically, data from these programs have played a major role in revealing these growth changes in European forests (Arovaara et al. 1984; Kauppi et al. 1992), and have more recently permitted to point out to the likely role of climate warming in enhancing forest growth in boreal contexts (Kauppi et al. 2014; Wu et al. 2014). Surprisingly though, these broad-scale investigations ignore the potential role of tree species and climate contexts in structuring these changes. As an exception, Gschwantner (2006) in Austria offers a multi-species comparison of growth changes, and inquires about the role of climate.

In this study, we investigated recent growth changes in the French forests, belonging to the European temperate and Mediterranean area. These forests cover >16 million ha and are representative of oceanic, continental, Mediterranean and mountain contexts. According to the ‘European Forest Types’ classification (EFT, Barbati et al. 2014), French forests hence encompass all except for the ‘boreal forests’ type, and rank first for the number of forest types covered. The diversity in tree species diversity is significant (Morneau et al. 2008), with 12/18 species dominating forest areas of >500.000/>200.000 ha, respectively (IFN 2006). The French NFI therefore provides an important opportunity to investigate recent forest growth changes across climatic contexts and tree species of Western Europe.

We studied changes in stand basal area increment per hectare (BAI) and their relationships with recent climate in major European species dominating the forest area, and found in mountain, temperate lowland and Mediterranean contexts. The questions addressed in this contribution were as follows: Q1. Do tree species exhibit recent (1980–2007) environment-driven growth changes, and what are variations among them? Q2. Are such possible differences related to the climatic ranges in which these species grow and to recent climatic warming? Is climate a primary determinant of these differences?

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Species under study

Eight species were analysed that range from cold-adapted to drought-tolerant species, and are found in contrasted climatic ranges (Barbati et al. 2014; Köble and Seufert 2001, Fig. 1). These included Silver fir (Abies alba Mill, a perialpine species) and Norway spruce (Picea abies Karst, a boreal species) hereafter named ‘mountain’ species, Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris L, ranging from the boreal to the sub-Mediterranean zone) and common beech (Fagus sylvatica L, a pan-European species) as ‘generalist’ species, sessile (Quercus petraea Liebl) and pedunculate (Quercus robur L) oaks as ‘temperate lowland’ species and pubescent (Quercus pubescens Willd, a sub-Mediterranean species) oak and Aleppo pine (Pinus halepensis Mill., found all around the Mediterranean sea) as ‘Mediterranean’ species. These species further represent 60% of the growing stock in France. The French territory encompasses both the warmer and colder margins (depicted by their Northern or upper distributional limits) of A. alba, P. abies, F. sylvatica, the warmer margins of Q. petraea and Q. robur and the colder margins of Q. pubescens and P. halepensis. None of these is covered for P. sylvestris.

Spatial distribution of the NFI sample plots for the 8 species under study. The letters in parenthesis indicate the climatic context of species occurrence: MO mountain, G generalist, TL temperate lowland, ME Mediterranean. The sample plots correspond to pure and even-aged stands. The grey scale represents elevation a.s.l.

2.2 NFI data selection and computation of dendrometric variables

We used NFI data collected between 1976 and 2008. The French NFI is based on temporary plots distributed over a systematic grid of 1 × 1 km. Between 1976 and 2004, this sampling scheme was applied by ‘Département’ administrative unit (hereafter dau), repeated around every 10 years (Robert et al. 2010), and not synchronous in the different dau. In 2004, the sampling design was changed to cover the whole forested area annually, and is since based on a yearly systematic grid of 10 × 10 km shifted each year. We included the four annual inventory samples available when the study was initiated (2005–2008). NFI sampling plot design is described in Appendix 1.

We focused on single-species dominated even-aged stands, for which concepts for measuring stand stocking (growing capital) and developmental stage exist (Skovsgaard and Vanclay 2008) and can be controlled in models evaluating growth changes. These communities therefore form references for addressing environment-driven impacts at species scale (Tilman 1988). A stand pureness criterion in tree species of >70% of the plot basal area was applied (Charru et al. 2010). Even-agedness was controlled using NFI ‘stand structure’ variable. Detailed selection criteria are provided in Appendix 2. A total of >25,000 NFI plots were selected for this study (Table 1), corresponding to >315,000 sampled trees.

Stand growth was represented by the 5-year stand basal area increment (BAI) at 1.30 m height per ha (Charru et al. 2010), computed from comprehensive tree diameter and cumulated 5-year radial increment core measurements (ri5) on the NFI plots (procedure presented in Appendix 3) above the countable threshold of 7.5 cm dbh.

Because ri5 measurements exclude the current year of inventory (partial ring), the last growth year covered in the increments is ‘2007’. The ri5 were dated by their median calendar year. Consequently, data collected between 1976 and 2008 correspond to increments dated from 1973 to 2005 as median years. Stand developmental stage was represented by stand top height (H 0), calculated as the mean height of the 100 thickest trees per hectare (Matèrn 1975) at the time of inventory. Stand age was discarded as a measure of developmental stage as it turns an unstable proxy in a growth change context where trees of a same age but of different establishment dates will not have the same size (Bontemps et al. 2009; Bontemps and Esper 2011), on which physiological development processes further depend (e.g. Ryan et al. 1997) . Top height was also preferred to diameter proxies as it remains less sensitive to spacing and thinning effects. Stand stocking influences stand growth and can be modified over time by changes in silvicultural prescriptions. It was therefore controlled by a relative density index (RDI, Reineke 1933), using species-specific self-thinning relationships developed from the same NFI data (Charru et al. 2012), and measures of stand density and quadratic mean diameter at the time of inventory.

2.3 Environmental data

Two sets of environmental data were used in the analysis (Table 2). The first one was a set of historical data describing plot environmental conditions and matching the periods of ri5 increment formation. This set was used to identify environmental predictors of stand BAI (growth-environment relationships, see section 4). Monthly climatic variables were extracted from the nearest ‘Météo-France’ climatic station (average distance from plots comprised between 9.9 and 18.3 km depending on tree species). Plot soil nutritional indicators (pH, soil carbon to nitrogen ratio or C/N, and base to total cation ratio or S/T) and soil water capacity were inferred from bio-indication methods applied to NFI floristic surveys (Gégout et al. 2003) and NFI soil description, respectively.

The second dataset corresponded to temporal average data, representative of local environmental conditions over larger time periods. This set was used to account for spatial variations in site conditions into statistical models of BAI, independently from possible historical changes in these conditions whose effect is described by a temporal growth change (site index can no longer be used for the purpose of controlling site in growth models, as it is prone to temporal changes and this effect would absorb the changes investigated). It included climate normals (30 years, Bénichou and Le Breton 1987) and 15-years spatializations (GIS layers) of nutritional indicators quantified from NFI plot data (Table 2).

Since floristic surveys and soil data were not available for all plots in the two first NFI cycles, the number of plots with historical data is lower than the initial number of selected plots (Table 1). Importantly, RDI and H 0 were not highly correlated to environmental predictors (correlation |r| < 0.2 for all environmental predictors and species) discarding any absorption of environmental signals.

2.4 General modelling framework

To answer question Q1, species-specific growth changes were estimated over each species sample, where growth was filtered out from the effects of stand stocking, developmental stage and permanent site factors by a statistical modelling approach (Charru et al. 2014). To answer question Q2, relationships between the previously estimated species-specific growth changes and indicators of climate normals and of contemporary climatic change specific to each species sample were explored using a correlative approach. The modelling flow implemented in the study is synthesized in Fig. 5 (Appendix 4 ).

To address Q1, we used a framework similar to Bontemps et al. (2009) and Charru et al. (2014) where BAI was modelled as a multiplicative function of stand stocking level, developmental stage and site fertility effects, then linearized by log-transformation:

where site fertility is allowed to vary in time, as it is modified by environmental changes and f 3 is the stand productivity allowed by site conditions (Bontemps and Bouriaud 2014). Functions f 1 and f 2 represent the respective effects of stand density and developmental stage on stand BAI.

The effects of average site fertility conditions and environment-driven growth changes (depending on time) on BAI are then distinguished (Bontemps et al. 2009; Charru et al. 2014):

where Site fertility0 describes site fertility at a reference state, and function f 4 corresponds to the temporal change in BAI to be estimated. In the study, we opted for a direct control of site fertility by temporal averages of environmental indicators (see section 3, Table 2 and below).

2.4.1 Estimation of tree species temporal changes in stand BAI (Q1)

The control of average site conditions in Eq. 2 required identifying species-specific environmental predictors of BAI as a first step. This was achieved by regressing stand BAI, corrected from the effects of stand stocking and developmental stage, against historical environmental predictors. In a second step, the previous species-specific predictors were included in their average form (see section 3) in comprehensive BAI models including a temporal change (Eq. 2).

Identification of species-specific environmental predictors of BAI (step 1)

The log-increment ln (BAI) was regressed against indicators of stand stocking (RDI) and developmental stage (H 0) by OLS (ordinary least squares) regression with different transformations tested (Appendix 5) and corrected from these effects. The resulting ln (BAI)cor was modelled as a function of historical environmental indicators representing site fertility (Eq. 2):

where the X i are historical environmental indicators contemporary to stand growth (Table 2, climatic indicators from October to December where those of months preceding the growing season) tested with quadratic effects to identify potential curvilinear responses, and g i and h i are the associated parameters. Hats describe estimates fitted in the previous step (Appendix 5).

We used partial least squares regression (PLS, Geladi and Kowalski, 1986) as an objective selection procedure for the X i, adapted to high-dimensional sets of partially correlated predictors as observed with environmental data (Carrascal et al. 2009). PLS models were fitted using the plsr package of the R software (Wehrens and Mevik 2007; R Development Core Team 2009) and the kernel PLS algorithm on normalized variables. Predictor selection was based on individual jackknife tests (Martens and Martens 2000) and their contribution to the R2. Details on the selection of predictive components and predictors are given in Appendix 6. Predictors were seasonally aggregated (temperature, water balance and radiations) when found of a similar effect on BAI over successive months.

Modelling estimation of stand BAI changes by species (step 2)

Comprehensive BAI models including a temporal change (Eq. 2) and average site fertility, represented by average environmental indicators (Table 2) were fitted:

where ε are iid Gaussian errors, t is the median year of BAI increment and Site fertility0 was substituted with linear combinations of environmental predictors selected in step 1, and taken in their average form (Table 2). These predictors were retained when they were not strongly correlated between each other (|r| < 0.5) and significant (p < 0.05). When two predictors were highly correlated, we retained that most increasing R2. We also tested for multiplicative interactions between these predictors.

We finally tested for an effect of time (f 4 in Eq. 4). The median calendar year ‘1982’ (Dateref) was fixed as a common reference for all species, as a trade-off between data availability and temporal cover. The final study period is therefore 1982–2005 as expressed in median years of increments, or 1980–2007 for the total growth period. Three different nested forms were tested for this temporal effect (linear, quadratic or third-order polynomial) to offer some flexibility in description of growth change temporal course:

where t is the median year of each 5-year BAI, Dateref is the reference date for measuring the temporal trend, so that f 4,i (Dateref) = 0. This temporal effect is multiplicative on a BAI scale (we have exp (f 4,i (Dateref)) = 1) and therefore measures a relative change in BAI over the period (Bontemps et al. 2009).

Resampling and bootstrap fits for temporal homogenization of site conditions

In the older NFI design (1976–2004), irregular distribution of dau inventory over time generated temporal imbalances in the site conditions sampled that could bias estimations of temporal BAI changes. For each species sample, we thus applied a resampling procedure of NFI plots (adapted from Bertrand et al. 2011) to ensure a comparable distribution of environmental conditions over time in each species sample. The principle was to resample NFI plots available in successive 2-year periods so that the distribution of each environmental permanent/average indicator influential on species growth in the comprehensive growth models matches their reference distributions as defined from the systematic sampling grid (new NFI sampling design 2005–2008). A principal component analysis (PCA) of these environmental predictors was used to reduce the number of distributions to be matched (Appendix 7).

For each species sample and for each 2-year period between 1976 and 2008, 500 balanced subsamples of 50 NFI plots were produced (Fig. 6 in Appendix 7) and randomly assembled to form 500 bootstrap samples covering the whole period 1982–2005 (such subsamples were also formed for the recent period 2005–2008, these being however immune of environmental imbalance as the whole territory is sampled each year). BAI models (Eq. 4) were fitted over these 500 samples, providing means and standard deviations for model parameters.

Nested formulations for BAI changes (‘trend complexity’, Eqs. 5 to 7) were tested and compared by F tests of nested models. A mathematical form was preferred to a simpler one when >95% of the tests (over the 500 fits) were significant. In some cases, the decision was based on a test consensus (never below 70%, Table 5). From the 500 bootstrap fits, mean species growth changes were computed using bootstrap means of associated parameters:

where i is an index for the bootstrap samples, and hats indicate parameter estimates.

These fits were also used to compute 95% bootstrap bilateral confidence intervals for species BAI changes (Efron 1979). To get an overview on the temporal growth anomalies, we last extracted the partial predictions for calendar year effect (after removing all effects from BAI but that of calendar year), and averaged these by median increment date over the 500 fits.

2.4.2 Role of tree species climatic habitat and of recent climatic change in stand BAI changes (Q2)

To investigate the role of species climatic habitat in their growth changes, we first computed cross-species correlations between species average BAI changes (BAIchg = \( \overline{f_4}\kern0.5em \left(2005-1982\right) \), with 2005 as the last median year available, Eq. 8) and mean annual temperature and annual precipitation normals, averaged over species samples. Second, we assessed recent climatic change, i.e. temporal trends in the sample averages of annual precipitation and annual averages of mean, minimum and maximum temperatures (Météo-France data) over the period 1980–2007, using simple linear regression against calendar year (Appendix 8). We then explored cross-species differences in climatic change, and how they correlated with sample averages of climate normals and with species BAI changes.

3 Results

3.1 Estimation of tree species temporal changes in stand BAI (1980–2007)

3.1.1 Identification of species-specific environmental predictors of BAI (step 1)

Goodness-of-fits (R2) of PLS regression models intended to identify environmental predictors of BAI on a species level (Eq. 3) ranged between 10 and 34%, and were much higher for mountain species and F. sylvatica than for other species. Partial R2 of predictors selected ranged between 2 and 18% (further statistics in Appendix 6 ). An overview on the selected predictors and their effects is provided in Table 3.

Some variables had a similar effect on most species’ growth, including the positive effect of soil water capacity (SWC) and soil water balance (SWB) during the growing season (with however slight timing differences), or that of soil nutrition (C/N ratio, pH). Most species responded positively to winter (P. sylvestris and Mediterranean species, though with curvilinear response) or spring/summer minimal temperatures (mountain species). Winter radiation had a negative effect for mountain species, P. sylvestris, F. sylvatica and Q. petraea. Summer radiation had a positive effect for A. alba and P. sylvestris. Maximal temperatures had more contrasted effects than minimal temperatures, consistent with species climatic habitat, whereas mountain species responded positively to June (P. abies) or May (A. alba) maximal temperature, P. sylvestris and the Mediterranean species hence responded negatively to summer or spring maximal temperature. F. sylvatica was the only species to show a strong negative response to winter maximal temperature. It also responded positively to April maximal temperature. Furthermore, A. alba and Q. pubescens showed a sensitivity to summer soil water deficit (SWD).

3.1.2 Modelling estimation of stand BAI changes by species (step 2)

Selected environmental predictors of species BAI were introduced in the BAI models (Eq. 4 without temporal effect, Table 4). Strong correlations between predictors led to discard some of them. Quadratic relationships found (temperature, water balance, radiation) were always concave, suggesting responses with optima. We retained interactions in three species, mainly involving SWC (Table 4). Model R2 varied between 42 and 50%, depending on tree species. Site predictors accounted for 4 to 28% of these R2. Increases in R2 were greater for F. sylvatica, A. alba, P. abies and P. sylvestris (+17% on average) than for Quercus species and P. halepensis (+7% on average).

Temporal growth changes (Eqs. 5 to 7) were then tested for each species (Table 5). For some species, resampling proved inefficient for some 2-year periods that were discarded and account for local gaps in growth chronologies (P. halepensis, P. sylvestris and Q. pubescens; Fig. 2). A significant temporal change was found for all species but Q. robur and P. sylvestris. Depending on the species, either linear (Q. pubescens and A. alba), quadratic (P. abies and F. sylvatica) or degree-3 polynomial (Q. petraea and P. halepensis) effects of year were retained. Relative (%) and absolute (m2 BAI/ha/5 years) temporal changes in BAI between median years 1982 and 2005 (period 1980–2007, hereafter, all dates apply in median years of extreme increments) are reported in Table 5.

Relative change in stand BAI and temporal anomalies for the 8 species under study over the period 1980–2007. The period covered corresponds to median increment years 1982–2005. Bootstrap fits are represented in light grey (trends, Eqs. 5 to 7) and dark grey (anomalies). Unique solid lines represent the species trends (dark grey) and anomalies (black) averaged over the 500 bootstrap fits. Dotted lines represent the 95% bootstrap bilateral confidence intervals for BAI changes. These changes range between +42% (P. abies) and −17% (Q. pubescens). Not significant for P. sylvestris and Q. robur

Important between-species differences in BAI changes were observed over the period under study (Fig. 2, Table 5). BAI strongly increased for mountain species (P. abies and A. alba). The highest increase was observed for P. abies, with a recent acceleration and a final level of +42% in 2005 as compared to 1982. The increase was linear for A. alba, reaching +19% in 2005. Generalist and lowland species showed moderate or absence of growth change. For F. sylvatica and Q. petraea, an increase in BAI between 1982 and 1995/2000 was found, followed by a decline in recent years, bringing growth close to its level of 1982. No significant change was found for Q. robur and P. sylvestris. A continuous decline in the BAI of Q. pubescens was found, amounting to −17% in 2005 relative to 1982, while P. halepensis exhibited an increase in BAI between 1982 and 1995, with however temporal uncertainty attached, followed by a sharp decline in the years 2000. For all species, the level of uncertainty in BAI change in 2005 was around ±10% (Table 5).

Temporal anomalies in species BAI revealed strong variations from one median year to another (Fig. 2). Periods of high and low growth could hence follow each other. A majority of tree species showed an important growth decrease in the years 2000s. This decline accounted for the deceleration or trend inversion found for some species (F. sylvatica, Q. petraea, P. halepensis) in recent years. In addition, remarkable moderate or rapid recovery in BAI between the median years 2004 and 2005 was found for 5 out of 8 species.

3.2 Role of tree species climatic habitat and of recent climatic change in stand BAI changes (Q2)

3.2.1 Relationships between normal climate and BAI changes

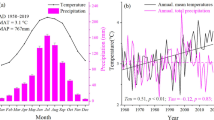

A clear correspondence between species BAI changes (BAIchg) and their climatic habitat was highlighted (Fig. 3). BAIchg then showed a remarkable negative correlation with the sample average of mean annual temperature (r = −0.89, p = 0.003, Fig. 4a), and a positive one to annual precipitation (r = 0.92, p < 0.002, Fig. 4b). Inversion points in the sign of BAI changes along temperature (from positive to negative) and precipitation (from negative to positive) gradients were also identified. The strong cross-species correlation between temperature and precipitation (r = −0.90, p = 0.002) further indicated a strong association between these two climatic indicators over the territory under study. Thus, these relationships indicated a main role of climatic habitats in the differentiation of species growth changes, with recent growth declines (resp. increases) in warmer and drier (resp. colder and wetter) contexts where water (resp. temperature) form primary limitations, respectively. A role for climate warming in the growth changes observed was therefore suggested.

Relationships between species BAI changes and recent climatic averages and climatic trends. a and b Relationships between species changes in stand BAI (BAIchg, period 1982–2005 in median years, 1980–2007 for the total period) and species sample averages of mean annual temperature (a) and annual precipitation (b, climate normals). c Relationships between minimal (black)/mean (grey) annual temperature changes over 1980–2007 and averages of minimal/mean annual temperatures over the same period (sample averages). d Relationships between species changes in stand BAI and recent trends in annual averages of minimum and mean temperature. Pa Picea abies, Aa Abies alba, Ps Pinus sylvestris, Fs Fagus sylvatica, Qp Quercus petraea, Qr Quercus robur, Qpu Quercus pubescens, Ph Pinus halepensis

3.2.2 Relationship between climatic and BAI changes

Recent climatic change

Linear analyses of recent climatic change across species samples over 1980–2007 revealed (Appendix 8) significant increases in mean annual temperature (+0.77 to +1.21 °C, maximum p < 0.02), even stronger in the annual average of maximal temperature (+1.10 to +1.29 °C, maximum p < 0.01) in all species samples. Significant increases in minimal temperature (+0.25 to +1.13 °C, Fig. 7 in Appendix 8) were found in all samples but those of Q. pubescens and P. halepensis, i.e. Mediterranean species. No significant change in total annual precipitation was found. A slight trend to increase (+7 to +47 mm) in all species samples but southern ones was however noticed (−11/−2 mm for Q. pubescens/P. halepensis, respectively). Drier periods were also observed in, e.g. 1989–1991 and 2003–2005 (Fig. 8 in Appendix 8). Consequently, all species studied faced significant recent climate warming and no significant change in precipitation over the period analysed, suggesting increased water stress/lower temperature stress in drier/colder contexts, respectively.

Changes in temperature and precipitation over the period 1980–2007 were also matched against climatic averages of the same period (Appendix 8). Significant negative correlations were found for minimum temperature (r = −0.82, p = 0.01, −0.18 °C change/°C average, R 2 = 0.67, Fig. 4c, Appendix 8) and mean annual temperatures (r = −0.75, p < 0.03, −0.09 °C change/°C average, R 2 = 0.57), indicating that warmer contexts (warmer plains and Mediterranean area, also the drier ones) recently experienced lower climatic warming than colder contexts (mountains and colder plains, also the wetter ones). No correlation was found for maximum temperature (p = 0.80, Fig. 6 in Appendix 8). Although not significant, changes in annual precipitation were positively correlated to precipitation averages (r = +0.79, p < 0.02, +0.12 mm change/mm average, R 2 = 0.63, same figure), indicating a trend to higher increases in wetter contexts (Fig. 9).

Relationship with BAI changes

Differences in recent climatic warming across species samples (minimum and mean annual temperature) thus appeared consistent with differences in species BAI changes. Accordingly, BAIchg was found positively and significantly correlated with average trends in minimal (r = +0.78, p = 0.02, +50% BAI change/°C increase 1980–2007) and mean annual temperature (r = +0.75, p = 0.03, +88% BAI change /°C increase 1980–2007, Fig. 4d). These relationships therefore suggested that uneven climate warming across the French territory was a further possible cause of species differences in BAI changes, with higher growth changes observed in colder samples where climate warming was more intense. Though precipitation changes were not significant, their important positive cross-sample correlation with minimum and mean temperature changes could only amplify this effect (r = +0.77/0.75, p < 0.05).

In summary, both the mean climatic context and climate warming of species samples were strongly correlated to species BAI changes, with greater growth increases found in colder/wetter contexts where climate warming, and secondary precipitation changes, have also been more acute, and no trend or even growth decreases in warmer/drier contexts with significant but less acute climate warming (Appendix 8). Strong correlations in climate and climate change indicators did not allow fit simultaneous regression models for BAIchg. The clear interpretative insights delivered by this correlation structure however made it unnecessary.

4 Discussion

A primary aim of this paper was to assess recent forest growth changes over a period of rapid climate warming, and how they may vary in magnitude among a set of eight major western European tree species developing in contrasted climatic ranges (Q1). A second aim was to investigate whether and to what extent species climatic habitats as well as spatial differentiation in climate warming may play a role in this differentiation of species growth changes (Q2). These issues were addressed using NFI data and statistical models, aspects that are first discussed.

4.1 Relevance of NFI data for estimating growth changes

Data from the French NFI provide spatially inclusive and repeated information on forest growth. With >25,000 plots covering the 8 species under study, and a temporal cover of about 25 years, the spatio-temporal trade-off with dendrochronology approaches is obvious. Although restricted, and as such able to favour ‘false negatives’ in the detection of growth changes, the study period advantagedly covers the warming period discernible in temperature chronologies since the mid 1980s onward (Jones et al. 2012). It also grants that longer-term silvicultural or genetic drifts cannot influence the changes detected. The magnitude and significance of the growth changes evidenced and their variety among tree species (Fig. 2) demonstrate that these changes are rapid, and NFI data are adequate to reveal them. Their magnitude also suggests that climate warming is currently of major impact onto forest ecosystems. The main issue in using NFI data was the space–date imbalance inherent to the older sampling design implemented by ‘department’ unit (dau), and it was solved by a resampling approach that proved efficient in balancing the distribution of site predictors identified to impact species growth across a temporal gradient (Fig. 6 in Appendix 7), although it led to discard some temporal sub-periods in three species (Fig. 2). Since such imbalance poses an intrinsic challenge for forest information update in forest reporting, the French inventory has turned systematic and continuous (Hervé et al. 2014) in 2005. This current trend in forest inventory (see also Gillespie 1999 in the USA) will in particular make the assessment of future changes in forest growth straighter.

4.2 Modelling approach

Because forest growth is depending on several factors including the developmental stage, stand stocking and site factors, growth changes could not be directly observed, and required statistical models to isolate the temporal signal in stand BAI (Charru et al. 2010). Species-specific models were thus developed on a wider geographic extent than is usually practised (e.g. Dhôte and Hervé 2000, Yue et al. 2014), and were found accurate. First, they accounted for 42 to 51% of total stand BAI variation, a satisfactory level in light of the several sources of uncertainty inherent to NFI data (small-plot inventory, 1-km resolution in plot location), to study scale (e.g. genetic structure in tree populations not accounted for) and to available environmental information (resolution of climatic data and maps of nutritional indicators). In comparable approaches on coniferous species-dominated forests in Sweden and Austria, Elfving and Tegnhammar (1996) and Gschwantner (2006) obtained R2 of very comparable orders of magnitude. Second, the effects of dendrometric variables were found consistent with the processes they represent, including positive effects of stand stocking level, and negative effects of stand developmental stage (Table 4). The short-term effect of thinning intensity was not tested for (Bouriaud et al. 2016), as the standard NFI protocol did not provide accurate estimates of plot harvest fluxes. As a path for progress, systematic re-measurement of NFI sample plots has been introduced in 2010 (Hervé et al. 2014), and will allow proper control of silviculture intensity in the future. Last, we opted for controlling site fertility by direct environmental indicators instead of dendrometric proxies (Bontemps and Bouriaud 2014), with PLS regression as a tool for predictor screening and selection (Table 3). Inclusive decision rules were implemented in the PLS regression approach (Appendix 6) so that important predictors of BAI unlikely remained undetected. While in-depth study of species autecology was not the purpose of this paper, the predictors identified were found to have general and ecologically consistent effects, including positive effects of water availability, positive effects of soil organic matter mineralization rate (C/N) and positive effects of minimal temperatures. They also revealed original seasonal patterns (e. g. negative effect of winter temperature and positive effect of spring temperature for F. sylvatica; Bontemps 2006; Kreyling 2010); or positive/negative effects of summer temperature for mountain/Mediterranean species, respectively, highlighting contexts where temperature is limiting on, or detrimental to, forest growth. As an important aspect, a limitation by minimum/maximum growing season temperature was identified for all species but P. sylvestris, Q. pubescens and P. halepensis, i.e. the species that exhibited growth increases over the past decades (Table 3). Yet, the resampling process failed for a restricted number of 2-year periods (Fig. 4) and introduced uncertainty as regards the growth dynamics of P. halepensis over 1985–95.

4.3 BAI changes observed over 1980–2007 and variations across species (Q1)

The strong species-dependence of BAI changes identified—differing in both sign, intensity and course (Fig. 2)—is a clear and main outcome of this study. These variations strongly contrast with previous findings of homogeneous responses between tree species across Europe (Boisvenue and Running 2006; Hellmann et al. 2016; Spiecker et al. 1996). They also suggest that large-scale studies disregarding the role of tree species in these responses oversimplify forest ecosystem response to environmental changes (Kauppi et al. 2014; Wu et al. 2014; found but not emphasized in Hellmann et al. 2016). Noticeably, these differences were found in relationship to the climatic habitat of each species (Fig. 3, Lindner et al. 2010): mountain species showed a very strong BAI increase (up to +42% over the period for Norway spruce), generalist and lowland species depicted moderately positive or no trend in BAI and Mediterranean species showed a BAI decline (down to −17% in pubescent oak). Negative changes in species growth found in southern contexts (Q. pubescens, P. halepensis) form a second major original finding of this study. They indicate that positive growth change reports accumulated in the literature up to recently reflect uneven consideration of European climatic contexts (Cienciala et al. 2016 in the Alps; Hellmann et al. 2016 in the boreal zone; Kahle et al. 2008 and Pretzsch et al. 2014 in Northern and Central Europe), including those large-scale contributions based on NFI data (Gschwantner 2006 in Central Europe; Elfving and Tegnhammar 1996; Kauppi et al. 2014; Wu et al. 2014 both in the boreal zone). The results also suggest that the statistical modelling methods implemented are appropriate for their detection, in a context of recurrent debate about a possible confounding with negative ageing trends in forest growth (Briffa et al. 1996; Esper 2003; Bowman et al. 2013).

Out of the eight species under study, Norway spruce growth may be subjected to altered management effects, as this species has been planted on agricultural soils in the Central mountain range over the period 1950–1970 (National Forest Fund Program). Exogenous genetic material used on soils richer than forest soils may have thus fostered a greater response to climate warming in this region, and inflate the mean growth change as suggested in a multi-regional study on this species (Charru et al. 2014). In addition, nitrogen deposition is not likely to play a role in the temporal growth changes reported. First, as a consequence of European decreases in NOx/NH3 emissions in Europe, trends in NO3 −/NH4 + deposition have been stable/negative respectively in French ICP level II plots over the period 1995–2007 (Pascaud et al. 2016), and total N deposition has decreased by 28% over 1993–2012 (IGN 2016). Second, sample averages of total N deposition where computed from the model of Croisé et al. (2005), yielding a restricted gradient of 7.3 to 8.7 kg ha−1 year−1 in annual N deposition across tree species, and further found not correlated to tree species BAI changes (p = 0.36).

4.4 Role of species climatic habitats in BAI changes (Q2)

The relationship found between recent species BAI changes and their climatic habitat (Fig. 3) suggested a primary control by climatic factors. Accordingly, species BAI changes were found strongly positively correlated to annual precipitation, and strongly negatively correlated to mean annual temperature (Fig. 4a, b), with noticeable sign inversion points, i.e. increased from warmer/drier conditions to colder/wetter conditions, where respectively water/temperature prevail as limitations. These findings were consistent with BAI-environment relationships found at the intra-specific level (Table 3), including a general limitation by water, and by spring and summer temperatures in mountain species (P. abies and A. alba) whereas P. sylvestris, Q. pubescens and P. halepensis responded negatively to maximum temperatures in the growing season. Noticeably, the footprint of climate in growth records was thus much clearer when screening cross-species average relationships than when analysing climatic gradients at species scale (see section 1.2 of Results and Tables 3 and 4), an aspect that may originate in the process of averaging local site conditions within species samples, while broadening the climatic gradients through cross-species aggregation. This stresses the importance of scale selection in revealing patterns of ecosystem responses to the environment (Siefert et al. 2012).

These remarkable relationships thus form a third major finding of this study, as they point out to the footprint of climate warming, with a negative impact on the growth of Mediterranean species found in warmer/drier contexts constrained by water availability, and conversely a positive impact on northern and mountain species with more abundant precipitation but a thermal constraint. Climate warming was furthermore found strongly differentiated over the territory and thus likely to play an additional role in the specific differentiation of growth changes, with increases in, e.g. minimal temperature ranging between +0.25 °C in the warmest contexts (P. halepensis) and +1.14 °C in the coldest ones (P. abies) over the study period (Fig. 4c and Appendix 8), and strongly correlated to species BAI changes (Fig. 4d). Annual precipitation showed slight, though not significant, increases for most species but the Mediterranean ones (same table). This pattern thus implied increased water stress in the associated drier contexts where precipitation was already lower (Mediterranean area). Recent climatic warming, through both its direct spatial differentiation (greater in colder and more temperature-limited contexts), and its interplay with water status (more detrimental in drier contexts), is therefore highlighted as the environmental signal strongly associated to recent forest growth changes in this area of Europe. Related findings on a regional scale (Bontemps et al. 2012; Charru et al. 2014 on P. abies) and species responses to climatic factors (Table 3) strongly support this view. Altogether, these results acknowledge the hypothesis that differences between tree species' recent growth responses are primarily driven by their climatic context. Hence, intrinsic species-driven variations in these changes appear limited when their position along climatic gradients is accounted for (Fig. 4), contrarily to some other studies (Babst et al. 2013; Büntgen et al. 2007; Friedrich et al. 2009). Since implications for adaptation differ in the species- or habitat-driven hypothesis, further research on the issue is crucial.

4.5 Anomalies in BAI chronologies

While occulted in the statistical process of growth change detection (Eqs. 5 to 7), yearly variations in stand BAI were clearly discernible in all species growth chronologies (Fig. 2). Growth measurements were however performed at a 5-year resolution with a smoothing effect on the variations depicted. This therefore stresses the importance of yearly climate variations in featuring forest growth on a wider geographic scale. Growth chronologies showed important between-species differences in these anomalies along the study period, but the latter also remained essentially negative in the early 2000s, including the year 2004 and to a lower extent 2005. In F. sylvatica, Q. petraea and P. halepensis, these anomalies even resulted in curving down the temporal trends fitted. This pattern is an obvious footprint of the climatic years 2003 (hottest year over the period in France, Gibelin et al. 2014) and 2004/2005 (exceptionally dry years, Spinoni et al. 2015, see also Appendix 8 for the study samples), in a generally warm period increasing aridity at these latitudes (Trenberth et al. 2013). At a European scale, the 2003 heat event remains associated with wide negative impacts on forest growth (Ciais et al. 2005; Granier et al. 2007). These observations again stress how rapidly climate warming can impact forest growth, with little insight to be gained from enquiries over earlier periods. As a major support to this idea, we identified growth declines in Q. pubescens, and over the latest study years in Q. petraea and F. sylvatica, i.e. broadleaved species for which secular growth increases have been largely reported over the twentieth century across temperate Europe (e.g. Bontemps et al. 2009; Dittmar et al. 2003 on F. sylvatica; Bergès et al. 2000 and Bontemps et al. 2012 on Q. petraea; Rathgeber et al. 1999 on Q. pubescens). With this respect, coniferous species growing in colder mountain ranges (P. abies and A. alba, see also Bošela et al. 2014; Gschwantner 2006; Kahle et al. 2008; in other European mountain ranges) and benefiting from climate warming (Fig. 4d) may form an exception in this area of Europe, and extend the outlooks delivered in boreal ranges (Kauppi et al. 2014; Wu et al. 2014). The recent growth decline identified in F. sylvatica is attested across Europe (Bontemps et al. 2012; Gschwantner 2006; Kint et al. 2012), with a greater magnitude at the species’ southern margin (Jump et al. 2006; Penuelas et al. 2008; Piovesan et al. 2008). The continuous growth decline reported for Q. pubescens is original, and largely unexpected for a species sampled at its northern margin. In Q. petraea, the sharp recent decline found in the 2000s has not been previously reported. It conflicts with strong increases in top height growth identified over the period (Bontemps et al. 2012), suggesting a discrepancy in the response of primary and secondary growth to environmental changes, related to, e. g. difference in their phenology and the higher exposure of secondary growth to summer drought (Jackson et al. 1976). While the absence of growth signal in P sylvestris is consistent with Kint et al. (2012) in Belgium, it may also be due to a lack of data following resampling (Fig. 2, Appendix 7). Growth in P. sylvestris has also been reported to increase at its northern/continental range (Elfving and Tegnhammar 1996; Kahle et al. 2008; Mellert et al. 2008), whereas declines were observed at its southern range (Martinez-Vilalta et al. 2008; Vila et al. 2008). This may suggest gradual shift from a negative to a positive change, when moving from the warmer to the colder margins of this species’ distribution.

5 Conclusions

This study demonstrates that climate warming is a predominant driver of recent forest growth changes in Western Europe, and diversely impacts forests with a primary dependence on the climatic habitats of tree species. Over a restricted period of 25 years, the magnitude of these changes suggests that rapid climate warming has strong impact onto forest growth, and raises concern for the future vitality of species growing in warmer ranges, including those meridional species whose northern margins were covered in the analysis (Pinus halepensis and Quercus pubescens). They also suggest a discrepancy between inferred future species distribution and productivity responses to climate change (Kirschbaum 2000). Arising literature on the issue (Dolos et al. 2015) reports converse findings of recent increase in species growth at their southern margins where aridity has increased (Tegel et al. 2014 on common beech), pointing out to research needs on how species respond to their abiotic environment. The present analyses also demonstrate that NFI form an invaluable tool for monitoring forests’ vitality in extended contexts, with a major role to be played in a still warmer future.

References

Arovaara H, Hari P, Kuusela K (1984) Possible effect of changes in atmospheric composition and acid rain on tree growth. An analysis based on the results of Finnish National Forest Inventories. Communicationes Instituti Forestalis Fenniae 122:4–14

Babst F, Poulter B, Trouet V, Tan K, Neuwirth B, Wilson R, Carrer M, Grabner M, Tegel W, Levanic T, Panayotov M, Urbinati C, Bouriaud O, Ciais P, Franck D (2013) Site- and species-specific responses of forest growth to climate across the European continent. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 22:706–717

Barbati A, Marchetti M, Chirici G, Corona P (2014) European Forest Types and Forest Europe SFM indicators: tools for monitoring progress on forest biodiversity conservation. For Ecol Manag 321:145–157

Becker M (1989) The role of climate on present and past vitality of silver fir forests in the Vosges mountains of northeastern France. Can J For Res 19:1110–1117

Bénichou P, Le Breton P (1987) Prise en compte de la topographie pour la cartographie des champs pluviométriques statistiques. La Météorologie 7:23–34

Bergès L, Dupouey J-L, Franc A (2000) Long-term changes in wood density and radial growth of Quercus petraea Liebl. in northern France since the middle of the nineteenth century. Trees 14:398–408

Bertrand R, Lenoir J, Piedallu C, Riofrio-Dillon G, de Ruffray P, Vidal C, Pierrat J-C, Gégout J-C (2011) Changes in plant community composition lag behind climate warming in lowland forests. Nature 479:517–520

Boisvenue C, Running SW (2006) Impacts of climate change on natural forest productivity - evidence since the middle of the 20th century. Glob Chang Biol 12:862–882

Bontemps J-D (2006) Evolution de la productivité des peuplements réguliers et monospécifiques de hêtre (Fagus sylvatica L.) et de chêne sessile (Quercus petraea Liebl.) dans la moitié Nord de la France au cours du XXe siècle. PhD Dissertation, ENGREF, Nancy, 448 p

Bontemps J-D, Bouriaud O (2014) Predictive approaches to forest site productivity: recent trends, challenges and future perspectives. Forestry 87:109–128

Bontemps J-D, Esper J (2011) Statistical modelling and RCS detrending methods provide similar estimates of long-term trend in radial growth of common beech in north-eastern France. Dendrochronologia 29:99–107

Bontemps J-D, Hervé J-C, Dhôte J-F (2009) Long-term changes in forest productivity: a consistent assessment in even-aged stands. For Sci 55:549–564

Bontemps J-D, Hervé J-C, Leban J-M, Dhôte J-F (2011) Nitrogen footprint in a long-term observation of forest growth over the twentieth century. Trees 25:237-251

Bontemps J-D, Hervé J-C, Duplat P, Dhôte J-F (2012) Shifts in the height-related competitiveness of tree species following recent climate warming and implications for tree community composition: the case of common beech and sessile oak as predominant broadleaved species in Europe. Oikos 121:1287–1299

Bošela M, Petras R, Sitkova Z, Priwitzer T, Pajtik J, Hlavata H, Sedmak R, Tobin B (2014) Possible causes of the recent rapid increase in the radial increment of silver fir in the Western Carpathians. Environ Pollut 184:211–221

Bouriaud O, Marin G, Bouriaud L, Hessenmöller D, Schulze ED (2016) Romanian legal management rules limit wood production in Norway spruce and beech forests. Forest Ecosystems 3:20

Bowman DMJS, Brienen RJW, Gloor E, Phillips OL, Prior LD (2013) Detecting trends in tree growth: not so simple. Trends in Ecology and Evolution 18:11–17

Briffa KR, Jones PD, Schweingruber FH, Karlén W, Shiyatov SG (1996) Tree ring variables as proxy-climate indicators: problems with low-frequency signals. In: Jones PD, Bradley RS, Jouzel J (eds) Climate variations and forcing mechanisms of the last 2000 years. Springer, Berlin, pp 9–41

Büntgen U, Frank DC, Kaczka RJ, Verstege A, Zwijacz-Kozica T, Esper J (2007) Growth responses to climate in a multi-species tree-ring network in the Western Carpathian Tatra Mountains, Poland and Slovakia Tree Physiology 27:689-702

Carrascal LM, Galvan I, Gordo O (2009) Partial least squares regression as an alternative to current regression methods used in ecology. Oikos 118:681–690

Charru M, Seynave I, Morneau F, Bontemps J-D (2010) Recent changes in forest productivity: an analysis of national forest inventory data for common beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) in north-eastern France. For Ecol Manag 260:864–874

Charru M, Seynave I, Morneau F, Rivoire M, Bontemps J-D (2012) Significant differences and curvilinearity in the self-thinning relationships of 11 temperate tree species assessed from forest inventory data. Ann For Sci 69:195–205

Charru M, Seynave I, Hervé J-C, Bontemps J-D (2014) Spatial patterns of historical growth changes in Norway spruce across western European mountains and the key effect of climate warming. Trees 28:205–221

Ciais P, Reichstein M, Viovy N, Granier A, Ogée J, Allard V, Aubinet M, Buchmann N et al (2005) Europe-wide reduction in primary productivity caused by the heat and drought in 2003. Nature 437:529–533

Cienciala E, Russ R, Šantrůčková H, Altman J, Kopáček J, Hůnová I, Štěpánek P, Oulehle F, Tumajer J, Ståhl G (2016) Discerning environmental factors affecting current tree growth in Central Europe. Sci Total Environ 573:541–554

Coumou D, Rahmstorf S (2012) A decade of weather extremes. Nat Clim Chang 2:491–496

Croisé L, Ulrich E, Duplat P, Jaquet O (2005) Two independent methods for mapping bulk deposition in France. Atmos Environ 39:3923–3941

Davison AC, Hinkley DV (1997). Bootstrap methods and their application, Cambridge University Press, 583 p

Dhôte J-F (1999) Compétition entre classes sociales chez le Chêne sessile et le Hêtre. Revue Forestière Française LI:309–325

Dhôte J-F, Hervé J-C (2000) Productivity changes in four sessile oak forests since 1930: a stand-level approach. Ann For Sci 57:651–680

Dittmar C, Zech W, Elling W (2003) Growth variations of common beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) under different climatic and environmental conditions in Europe—a dendroecological study. For Ecol Manag 173:63–78

Dolos K, Bauer A, Albrecht S (2015) Site suitability for tree species: is there a positive relation between a tree species’ occurrence and its growth? Eur J For Res 134:609–621

Efron B (1979) Bootstrap methods: another look at the jackknife. Ann Stat 7:1–26

Elfving B, Tegnhammar L (1996) Trends of tree growth in Swedish forests 1953-1992: an analysis based on sample trees from the National Forest Inventory. Scand J For Res 11:26–37

Esper J (2003) Tests of the RCS method for preserving low-frequency variability in long tree-ring chronologies. Tree-Ring Research 59:81–98

Friedrich DA, Trouet V, Büntgen U, Frank DC, Esper J, Neuwirth B, Löffler J. (2009). Species-specific climate sensitivity of tree growth in Central-West Germany Trees 23:729–739

Gégout J-C (2008) Validation de bio-indicateurs floristiques pour la surveillance de l’état nutritionnel des sols forestiers français à partir des données de l’Inventaire forestier national. Agroparistech, Inventaire Forestier National, Nancy, 47 pp

Gégout J-C, Hervé J-C, Houllier F, Pierrat J-C (2003) Prediction of forest soil nutrient status using vegetation. J Veg Sci 14:55–62

Geladi P, Kowalski BR (1986) Partial least-squares regression—a tutorial. Anal Chim Acta 185:1–17

Gibelin A-L, Dubuisson B, Corre L, Deaux N, Jourdain S, Laval L, Piquemal J-M, Mestre O, Dennetière D, Desmidt S, Tamburini A (2014) Evolution de la température en France depuis les années 1950. La Météorologie 87:45–53

Gillespie AJR (1999) Rationale for a national annual forest inventory program. J For 97:16–20

Granier A, Reichstein M, Breda N, Janssens IA, Falge E, Ciais P, Grunwald T, Aubinet M et al (2007) Evidence for soil water control on carbon and water dynamics in European forests during the extremely dry year: 2003. Agric For Meteorol 143:123–145

Gschwantner T (2006) Growth changes according to the data of the Austrian National Forest Inventory and their climatic causes, PhD Dissertation, BFW, Austria

Hansen J, Sato M, Ruedy R, Lo K, Lea DW, Medina-Elizade M (2006) Global temperature change. Proc Natl Acad Sci 103:14288–14293

Hari P, Arovaara H (1988) Detecting CO2 induced enhancement in the radial increment of trees. Evidence from northern timber line Scandinavian Journal of Forest Research 3:67–74

Hartl-Meier C, Dittmar C, Zang C, Rothe A (2014) Mountain forest growth response to climate change in the Northern Limestone Alps. Trees 28:819–829

Hasenauer H, Nemani RR, Schadauer K, Running SW (1999) Forest growth response to changing climate between 1961 and 1990 in Austria. For Ecol Manag 122:209–219

Hellmann L, Agafonov L, Charpentier Ljungqvist F, Churakova O, Düthorn E, Esper J, Hülsmann L, Kirdyanov A et al (2016) Diverse growth trends and climate responses across Eurasia’s boreal forest. Environmental Research Letter 11:074021

Hervé J-C, Wurpillot S, Vidal C, Roman-Amat B (2014) L’inventaire des ressources forestières en France: un nouveau regard sur de nouvelles forêts. Revue Forestière Française 66:247–260

IFN (1994) Manuel du Chef d’Equipe, Ministère de l’Agriculture, Nogent sur Vernisson

IFN (2006) La forêt française. Les résultats de la campagne d’inventaire 2005. Résultats nationaux présentés selon un découpage en cinq interrégions, Nogent-sur-Vernisson, 114p.

IGN (2016) Indicateurs de gestion durable des forêts françaises métropolitaines, edition 2015, Résults. Maaf-IGN, Paris, 343 pp

Jackson DS, Gifford HH, Chittenden J (1976) Environmental variables influencing the increment of Pinus radiata: (2) effects of seasonal drought on height and diameter increment. N Z J For Sci 5:265–286

Jones PD, Lister DH, Osborn TJ, Harpham C, Salmon M, Morice CP (2012) Hemispheric and large-scale land-surface air temperature variations: an extensive revision and update to 2010. J Geophys Res 117:29

Jump AS, Hunt JM, Penuelas J (2006) Rapid climate change-related growth decline at the southern range edge of Fagus sylvatica. Glob Chang Biol 12:2163–2174

Kahle HP, Karjalainen T, Schuck A, Agren GI, Kellomaki S, Mellert K, Prietzel J, Rehfuess K-E, et al. (eds) (2008) Causes and consequences of forest growth trends in Europe. EFI Research Report, EFI, Joensuu

Kauppi PE, Mielikäinen K, Kuusela K (1992) Biomass and carbon budget of European forests, 1971 to 1990. Science 256:70–74

Kauppi PE, Posch M, Pirinin P (2014) Large impacts of climatic warming on growth of boreal forests since 1960. PLoS One 9:e111340

Kint V, Aertsen W, Campioli M, Vansteenkiste D, Delcloo A, Muys B (2012) Radial growth change of temperate tree species in response to altered regional climate and air quality in the period 1901–2008. Clim Chang 115:343–363

Kirschbaum MUF (2000) Forest growth and species distribution in a changing climate. Tree Physiol 20:309–322

Köble R, Seufert G (2001) Novel maps for forest tree species in Europe. In: Proceedings of the 8th European Symposium on the Physico-Chemical Behaviour of Air Pollutants: "A Changing Atmosphere!", Torino (Italy), 17–20 September 2001. Data set available online at: http://afoludata.jrc.ec.europa.eu/index.php/dataset/detail/66.

Kotlarski S, Bosshard T, Lüthi D, Pall P, Schär C (2012) Elevation gradients of European climate change in the regional climate model COSMO-CLM. Clim Chang 112:189–215

Kreyling J (2010) Winter climate change: a critical factor for temperate vegetation performance. Ecology 91:1939–1948

Lamarche VC, Graybill DA, Fritts HC, Rose MR (1984) Increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide: tree ring evidence for growth enhancement in natural vegetation. Science 225:1019–1021

Lindner M, Maroschek M, Netherer S, Kremer A, Barbati A, Garcia-Gonzalo J, Seidl R, Delzon S et al (2010) Climate change impacts, adaptive capacity, and vulnerability of European forest ecosystems. For Ecol Manag 259:698–709

Lindner M, Fitzgerald JB, Zimmermann NE, Reyer C, Delzon S, van der Maaten E, Schelhaas M-J, Lasch P, Eggers J, van der Maaten-Theunissen M, Suckow F, Psomas A, Poulter B, Hanewinkel M (2014) Climate change and European forests: what do we know, what are the uncertainties, and what are the implications for forest management? J Environ Manag 146:69–83

Martens H, Martens M (2000) Modified Jack-knife estimation of parameter uncertainty in bilinear modelling by partial least squares regression (PLSR). Food Qual Prefer 11:5–16

Martin-Benito D, Gea-Izquierdo G, del Rio M, Canellas I (2008) Long-term trends in dominant-height growth of black pine using dynamic models. For Ecol Manag 256:1230–1238

Martinez-Vilalta J, Lopez BC, Adell N, Badiella L, Ninyerola M (2008) Twentieth century increase of Scots pine radial growth in NE Spain shows strong climate interactions. Glob Chang Biol 14:2868–2881

Matèrn B (1975) On estimating the dominant height, Royal College of Forestry. Dept. of Forest Biometry, Stockholm, 4pp

Mellert KH, Prietzel J, Straussberger R, Rehfuess KE, Kahle HP, Perez P, Spiecker H (2008) Relationships between long-term trends of air temperature, precipitation, nitrogen nutrition and growth of coniferous stands in Central Europe and Finland. Eur J For Res 127:507–524

Mevik B-H, Wehrens R (2007) The pls package: principal component and partial least squares regression in R. J Stat Softw 18:23

Morneau F, Duprez C, Hervé J-C (2008) Les forêts mélangées en France métropolitaine. Caractérisation à partir des résultats de l’Inventaire forestier national. Revue Forestière Française 60:107–120

Myneni RB, Keeling CD, Tucker CJ, Asrar G, Nemani RR (1997) Increased plant growth in the northern high latitudes from 1981 to 1991. Nature 386:698–702

Nellemann C, Thomsen MG (2001) Long-term changes in forest growth: potential effects of nitrogen deposition and acidification. Water Air and Soil Pollution 128:197–205

Niinemets U, Valladares F (2006) Tolerance to shade, drought, and waterlogging of temperate northern hemisphere trees and shrubs. Ecol Monogr 76:521–547

Pascaud A, Sauvage S, Coddeville P, Nicolas M, Croisé L, Mezdour A, Probst A (2016) Contrasted spatial and long-term trends in precipitation chemistry and deposition fluxes at rural stations in France. Atmos Environ 146:28–43

Penuelas J, Hunt JM, Ogaya R, Jump AS (2008) Twentieth century changes of tree-ring delta C-13 at the southern range-edge of Fagus sylvatica: increasing water-use efficiency does not avoid the growth decline induced by warming at low altitudes. Glob Chang Biol 14:1076–1088

Piedallu C, Gégout J-C (2007) Multiscale computation of solar radiation for predictive vegetation modelling. Ann For Sci 64:899–909

Piedallu C, Gégout J-C, Bruand A, Seynave I (2011) Mapping soil water holding capacity over large areas to predict potential production of forest stands. Geoderma 160:355–366

Piovesan G, Biondi F, Di Filippo A, Alessandrini A, Maugeri M (2008) Drought-driven growth reduction in old beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) forests of the central Apennines, Italy. Glob Chang Biol 14:1265–1281

Pretzsch H⇑, Biber P, Schütze G, Bielak K (2014) Changes of forest stand dynamics in Europe. Facts from long-term observational plots and their relevance for forest ecology and management. For Ecol Manag 316:65–77

R Development Core Team (2009) R: a language and environment for statistical computing. R foundation for statistical computing, Vienna

Rathgeber C, Guiot J, Roche P, Tessier L (1999) Quercus humilis increase of productivity in the Mediterranean area. Ann For Sci 56:211–219

Reineke LH (1933) Perfecting a stand-density index for even-aged forests. J Agric Res 46:627–638

Robert N, Vidal C, Colin A, Hervé J-C, Hamza N, Cluzeau C (2010) France. In: Tomppo E, Gschwantner T, Lawrence M, McRoberts RE (eds) National Forest Inventories—pathways for common reporting. Springer, Heidelberg Dordrecht London New York, pp 207–221

Ryan MG, Binkley D, Fownes JH (1997) Age-related decline in forest productivity: pattern and process. Advance in Ecological Research 27:214–262

Siefert A, Ravenscroft C, Althoff D, Alvarez-Yépiz JC, Carter BE, Glennon KL, Heberling JM, Su Jo I, Pontes A, Sauer A, Jo IS, Willis A, Fridley JD (2012) Scale dependence of vegetation–environment relationships: a meta-analysis of multivariate data. J Veg Sci 23:942–951

Skovsgaard J-P, Vanclay JK (2008) Forest site productivity: a review of the evolution of dendrometric concepts for even-aged stands. Forestry 81:13–31

Spiecker H, Mielikäinen K, Köhl M, Skovsgaard JP (eds) (1996) Growth trends in European forests. Springer, Berlin Heidelberg

Spinoni J, Naumann G, Vogt JV, Barbosa P (2015) The biggest drought events in Europe from 1950 to 2012. Journal of Hydrology: Regional Studies 3:509–524

Tegel W, Seim A, Hakelberg D, Hoffmann S, Panev M, Westphal T, Büntgen U (2014) A recent growth increase of European beech (Fagus sylvatica L.) at its Mediterranean distribution limit contradicts drought stress. Eur J For Res 133:61–71

Tenenhaus M (1998) La régression PLS - Théorie et pratique. Editions Technip, Paris

Thuiller W, Lavorel S, Araújo MB (2005) Niche properties and geographical extent as predictors of species sensitivity to climate change. Glob Ecol Biogeogr 14:347–357

Tilman D (1988) Plant strategies and the dynamics and structure of plant communities Princeton University Press. Princeton, New Jersey

Tomppo E, Gschwantner T, Lawrence M, McRoberts RE (2010) National forest inventories—pathways for common reporting. Springer, Heidelberg, Dordrecht, London

Trenberth KE, Dai A, van der Schrier G, Jones PD, Barichivich J, Briffa KR, Sheffield J (2013) Global warming and changes in drought. Nat Clim Chang 4:17–22

Turc L (1961) Estimation of irrigation water requirements, potential evapotranspiration: a simple climatic formula evolved up to date. Annals of Agronomy 12:13–49

Vidal J-P, Martin E, Franchisteguy L, Baillon M, Soubeyroux J-M (2010) A 50-year high-resolution atmospheric reanalysis over France with the Safran system. Int J Climatol 30:1627–1644

Vila B, Vennetier M, Ripert C, Chandioux O, Liang E, Guibal F, Torre F (2008) Has global change induced divergent trends in radial growth of Pinus sylvestris and Pinus halepensis at their bioclimatic limit? The example of the Sainte-Baume forest (south-east France). Ann For Sci 65:709

Way DA, Oren R (2010) Differential responses to changes in growth temperature between trees from different functional groups and biomes: a review and synthesis of data. Tree Physiol 30:669–688

Wehrens R, Mevik BH (2007) PLS: Partial least squares regression (PLSR) and principal component regression (PCR). R package version 2.1–0. ttp://mevik.net/work/software/pls.html

Wu C, Hember RA, Chen JM, Kurz WA, Price DT, Boisvenue C, Gonsamo A, Ju W (2014) Accelerating forest growth enhancement due to climate and atmospheric changes in British Colombia, Canada over 1956-2001. Scientific Reports 4:4461

Yue C, Kahle H-P, Kohnle U, Zhang Q, Kang X (2014) Detecting trends in diameter growth of Norway spruce on long-term forest research plots using linear mixed-effects models. Eur J For Res 133:783–792

Zang C, Hartl-Meier C, Dittmar C, Rothe A, Menzel A (2014) Patterns of drought tolerance in major European temperate forest trees: climatic drivers and levels of variability. Glob Chang Biol 20:3767–3779

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Inventaire Forestier National (French National Forest Inventory) for funding the present research and providing access to data. They express their special recognition to François Morneau (NFI) for sharing expertise on using NFI data. This work was also supported by the French Research Agency (ANR) through the ‘‘Oracle’’ project (CEP&S call, 2010). The authors last thank the two anonymous reviewers of the journal for their commitment and useful comments on a previous version of this manuscript.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Handling Editor: Aaron R. Weiskittel

Contribution of the co-authors

Marie Charru performed data and modelling analyses and wrote the initial version of the manuscript, Ingrid Seynave provided support on data preparation and provided ideas for climate change impact analyses, Jean-Christophe Hervé fostered and enabled research of French NFI data, Romain Bertrand provided support on data resampling methods, Jean-Daniel Bontemps designed the project, supervised the analyses, performed some data analyses on climate-growth relationships and rewrote later versions of the manuscript. In addition, all co-authors contributed to reviewing and writing the manuscript.

Appendices

Appendix 1. NFI sample plot design and measurements

NFI sampling plots are organized into four circular concentric subplots of 25, 15, 9 and 6 m radius. Data collected include environmental data (topography, soil characteristics and floristic survey) and stand characteristics measured in the 25-m subplot, and tree characteristics inventoried exhaustively over a countable threshold of 7.5 cm diameter at breast height (dbh) (6, 9 and 15 m radius subplot, for the small (7.5 cm < dbh < 22.4 cm), medium (22.5 cm < dbh < 37.4 cm), and larger (dbh > 37.5 cm) trees, respectively). Variables measured on each countable tree include dbh, bark thickness at breast height, total tree height and 5-year radial increment under bark (ri5) at breast height. Broken or cut trees are inventoried when the time elapsed since the event is assumed to not exceed 5 years.

Appendix 2. NFI plot selection criteria

As in Charru et al. (2010), we selected pure even-aged plots taken as reference community on the productivity of which influential factors like stand dynamics (stand stocking, ageing) and site fertility have a clear meaning and can be controlled accurately. We retained plots where the considered species represented over 70% of the stand basal area, with a minimum total cover of 50% of plot area. Furthermore, we targeted plots that were historically forested and where no change in species was carried out within the last 40 years. Because of the NFI countable threshold of 7.5 cm on dbh, tree inventory cannot be exhaustive in a fraction of young stand plots. To avoid plots where total stand BAI may be underestimated, we discarded plots of a quadratic mean diameter (Dg) below 10 cm. We also excluded plots of a regeneration density (trees not inventoried) above 500 trees/ha to avoid young stands where a large number of trees would be under the countable threshold.

Appendix 3. Calculation of stand BAI from NFI plot inventory

Stand basal area increment (BAI) per hectare was computed from plot data in three steps. In the first step, individual tree basal area increment under bark (bai) was calculated for living trees. In order to account for tree recruitment during the 5-year period (trees that crossed the countable threshold of 7.5 cm at breast height), we only considered the fraction of the increment corresponding to a dbh over 7.5 cm:

where bai is in m2/5 years, dbh is tree diameter at breast height in metres, BT is bark thickness in metres and ri5 is individual radial increment over the last 5 years at breast height in meters.

In the second step, we reconstituted the individual radial increment for ‘lost’ trees (dead, cut or damaged within 5 years preceding the inventory) from that reconstituted for living trees. It was calculated as the plot mean quadratic increment (which allows an unbiased reconstitution of a basal area increment), weighted by (i) a relative social status index defined as the ratio between individual dbh and plot mean quadratic diameter (Dhôte 1999); and (ii) the temporal fraction of the 5-year period preceding inventory during which lost trees were estimated to have grown (IFN 1994). Further details are given in the appendix of Charru et al. (2010).

In the third step, the stand level BAI was calculated as the sum of the individual bai, further using NFI plot weights in order to obtain a per hectare value.

where i refers to each individual tree, w i is the relative area weight of each tree at the time of inventory and ri5i is either measured or reconstituted. Therefore, the stand BAI corresponds to a gross increment in basal area (m2/ha/5 years) above the countable threshold of 7.5 cm at breast height, over a 5-year period.

Appendix 4. Modelling flow implemented for each tree species

Modelling flow implemented for each tree species. In order to isolate the temporal signal in growth, other factors must be first controlled including growing stock, stage of stand development and average/permanent site conditions. While indicators exist for the two formers, the latter cannot be controlled easily, e.g. by site index that changes over time, and environmental indicators must be used. Step 1 is intended for their selection, using a PLS regression approach. Once these environmental predictors are identified (X i), it turns possible to resample NFI plots from the older NFI sampling sketch where all administrative units were not sampled at the same time, resulting in a sampling design imbalance likely to cause false temporal effects. Thus, NFI plots in the older NFI design are bootstrapped to get samples in which the predictors X i match at any date (pair of years) the whole country distribution of these. A PCA is further implemented to reduce the initial dimensionality of the X i and only match 2 distributions defined by PCA axes. Then, step 2 can be implemented where all factors are controlled by relevant proxies and the samples are balanced over time. In this step, an appropriate mathematical approximation for temporal growth changes can be selected from bootstrap tests, and its uncertainty can be measured (Fig. 2 of the manuscript)

Appendix 5. Parameter estimates and summary statistics for the linear regression models of stand BAI against RDI and H0

Appendix 6. Component and variable selection in the PLS regression approach