Abstract

Honey bee workers show very flexible aging patterns. Their typical behavioral progression, from nurse bees to forager bees, is associated with an onset of aging symptoms. Here, we studied how immune-activation can affect nurse and forager bees differently. Nurse and forager bees of identical chronological age were injected with vehicle control or the bacterial cell wall components lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or peptidoglycan (PGN). Next, we monitored survival and tested the expression of three immune-related genes. We confirm that forager bees die sooner than same-aged nurse bees, independent of the type of immune challenge. The relative gene expression patterns of two immune-related genes differed between the nurse and forager honey bees as well as between the treatment groups. Our findings support that nurse and forager honey bees can respond differently to immune challenge, despite a lack of detectable differences in mortality between treatments. This response was specifically associated with the workers’ behavioral caste, as the chronological age was similar among all tested animals.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Honey bee colonies are maintained by elaborate social interactions between worker bees. Workers collect, process, and pass on food and engage in hygienic behaviors, nest defense, and thermoregulation (Seeley 1995). During adult life, most honey bee workers transition from one social task to another. Younger adult bees typically carry out in-nest tasks, such as food jelly production and nursing (nurse bees). Successively, they shift to outside tasks, mostly foraging for nectar and pollen (forager bees). Forager bees rapidly develop aging symptoms, including increased mortality, impaired behavioral performance, accumulation of lipofuscin (cellular “waste”), oxidative stress damage, and reduced numbers of functional hemocytes (circulating immune cells) (reviewed by Münch and Amdam (2013))). A decline in abundance of intact, circulating immune cells in forager bees could imply that honey bee immunity is a function of behavioral caste (Amdam et al. 2005). However, apparently contradicting this proposed negative association between immunity and foraging behavior is the upregulation of humoral immunity and phenol oxidase activity in foragers (Schmid et al. 2008; Wilson-Rich et al. 2008; Laughton et al. 2011).

After immune activation, humoral effector molecules are released into the hemolymph (insect blood) (reviewed by Hillyer (2016))) from the fat body (analogous to the mammalian liver and white adipose tissue). The fat body is central to the insect innate immune system, and it is, e.g., the production site of various antimicrobial proteins and peptides (AMPs) (reviewed by Hillyer (2016))). Honey bees feature the four signaling pathways that are typically associated with insect immune responses (i.e., Toll, immune deficiency (IMD), Janus kinase-signal transducer and activator of transcription (JAK-STAT), and Jun N-terminal kinases (JNKs)). However, compared to established model insects such as Drosophila melanogaster and Anopheles gambiae, the number of immune-related genes in these pathways is only one third in honey bees (Evans et al. 2006). This reduction might confer a more limited capability to fight pathogens or suggest that less-explored molecular mechanisms play a role in honey bee immunity (Evans et al. 2006).

One such less-explored pathway involves Vitellogenin (Vg). Vg is a lipoglycophosphoprotein that is more widely known for its role in egg-yolk formation. Vg is produced in the fat body of most female insects, including the functionally sterile honey bee workers. Honey bee Vg binds to dead bacteria (Salmela et al. 2015), supports immune cell functions (Amdam et al. 2005), and reduces oxidative stress (Seehuus et al. 2006). Vg hemolymph levels are higher in nurse bees compared to foragers. Hence, Vg levels are positively correlated with worker stress resilience and lifespan potential (Fluri et al. 1977; Amdam et al. 2005; Bordier et al. 2017). Causal roles of Vg have been verified via RNA interference-mediated gene knockdown of the vg gene. This knockdown reduces honey bee stress resistance and shortens lifespan, in addition to effects on behavior (reviewed by Münch and Amdam (2013))).

Recent experiments have contrasted the susceptibility of nurse and forager honey bees to multiple stressors, including starvation (Seehuus et al. 2006), heat, pesticides, and mechanical wounding (Bordier et al. 2017). Mechanical wounding represents an immune challenge that results in reduced vg gene expression in both nurses and foragers in some studies but not in others (discussed by Bordier et al. (2017)). Overall, there is considerable interest in effects of immune challenge in honey bee workers due to roles of diseases in the syndrome of colony collapse disorder (Laughton et al. 2011; Kazlauskas et al. 2016; Bordier et al. 2017; Li et al. 2018).

Here, we ask how immune challenge with lipopolysaccharide (LPS) or peptidoglycan (PGN) affects worker honey bees, and whether bees representing different castes (nurse and forager bees) respond differently. We performed an experiment where we compared survival and immune-related gene expression in nurses and foragers. We used a standard protocol to produce worker bees of the same chronological age but with different behavioral task. This setup, in which nurse and forager bees are of the same age, is a gold standard for comparing task-dependent differences in this species (Huang and Robinson 1992).

We compared LPS- and PGN-injected nurse and forager groups with control groups injected with PBS (vehicle). Thereby, mechanical wounding was experienced by all the bees used in this study. We monitored worker survival and the expression of three immune-related genes: two AMPs and the vg gene. Our results support that worker survival is task dependent and not strongly influenced by the specific immunogen treatments we used in this study. However, we find that nurse and forager bees display different gene expression patterns in response to challenge with LPS or PGN.

This report can be of interest to the community that uses the honey bee as a model in aging research, and more generally in fields that focus on how the immune system tackles challenges across the lifespan.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Bees

Honey bee foragers are usually chronologically older than nurse bees in natural colonies, which confound behavior with age. To eliminate such age bias, we adopted an established method that allowed obtaining foragers and nurses of identical chronological age, thus avoiding this problem (Huang and Robinson 1992). Three single-cohort colonies (SCCs) of honey bees were established at Arizona State University, Tempe, USA. Each SCC was assembled by allowing worker bees to emerge from pupation in the laboratory, paint mark them within 24 h (Uni Posca, Japan), and placing them together (N = 3000 workers) in a hive box containing one queen bee. Throughout the experiment, the three hives were monitored and managed to avoid that new workers emerged in the colonies. Thereby, the hives only contained workers of the same age. Under these conditions, the same-aged workers will divide labor between nursing and foraging (Huang and Robinson 1992).

2.2 Marking foragers in the SCC

After 15 to 17 days, we marked worker bees that were performing foraging tasks. These bees were painted with a new color, i.e., different from the color mark that the bees had already received within 24 h of emerging from the pupal stage. Foraging behavior was confirmed when bees returned to the colonies with pollen on their hind legs, or with a nectar load in their distended abdomen (Huang and Robinson 1992; Behrends et al. 2007).

2.3 Collecting nurses and foragers

After 21–22 days, we collected nurses and foragers in the morning before foraging activity began. Nurses were identified with one mark (the original mark received within 24 h of emergence) combined with having their heads inserted into cells of the brood comb that contained larvae (Munch et al. 2013). Foragers were identified by having the additional color mark that they had received when returning from a foraging flight at least 5 days prior to the sample collection. This procedure ensured that we collected primarily established foragers that had been expressing foraging behavior for several days (Munch et al. 2013).

2.4 Immune challenge

Nurses and foragers were anesthetized on ice in the laboratory and mounted on wax plates. They were injected abdominally with 1.5 μl phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, vehicle control), or two common immunogens using 701 LT Hamilton syringes and 31G needles (Sigma- Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA). The immunogens were 1.5 μl LPS derived from Escherichia coli serotype 055:B5 (0.5 μg/μl/PBS, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) or 1.5 μl of PGN derived from Staphylococcus aureus (0.5 μg/μl/PBS, Sigma-Aldrich, Saint Louis, MO, USA) (Richard et al. 2008; Laughton et al. 2011). Following injections, the worker bees were placed into small queen cages, with 7–9 bees per cage, and incubated at 33 °C (CO2 = 5%, relative humidity = 50–60%). Each cage contained a combination of foragers and nurses representing all the three treatment groups. Cages were provided with bee candy (Apifonda, Südzucker AG, Ochenfurt, Germany) and a water source.

2.5 Survival experiment

Workers were collected from the SCC on day 22 of the experiment. Sampling, injection, and incubation were performed as described in Sects. 2.3 and 2.4. Survival of the resulting bees in the queen cages was first monitored after 2, 4, 6, and 8 h, followed by monitoring every 3 h during the night and the following day (11, 14, 17, 20, 23, 26, 29, and 32 h), after which survival was recorded at 48 and 72 h postinjection. Seventy-two hours after the injection, none of the bees survived across all three colonies. The specific sample sizes for each treatment were as follows: N(urse)control = 68, NLPS = 75, NPGN = 61, F(orager)control = 67, FLPS = 70, and FPGN = 79 (Online resource Table S1).

2.6 RNA extraction and cDNA synthesis

Worker bees were collected at day 21 and 22 of the experiment, immobilized on ice 8 h postinjection. The gut and the stinger were removed, and the abdominal carcass was detached. The abdominal carcass, consisting mostly of cuticle and fat body, were placed in − 80 °C. RNA was extracted from 16 randomly picked samples in each treatment group by the general TRIzol method (Wang et al. 2012). The quality and quantity of RNA was determined by spectrophotometry (Nanovue, GE Healthcare). DNase (RNase-free, DNase kit, Applied Biosystems, Bedford. MA, USA) was added to the total RNA extract to remove trace DNA contaminants, and 1 μg of such treated RNA was used for reverse transcription using TaqMan® Reverse Transcription Reagents (Applied Biosystems, Bedford, MA, USA).

2.7 Quantitative real-time PCR analyses

First-strand cDNA was used for real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) assays on an ABI Prism 7500 Real-Time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, Bedford, MA, USA). Vitellogenin (AJ517411) (Wang et al. 2012), defensin-2 (NM_001011638.1) (Richard et al., 2008), and hymenoptaecin (NM_001011615.1) (Lourenco et al. 2013) were chosen for gene expression analysis. The samples were organized on the optic plates (96 wells) to allow for powerful statistical comparison of treatment groups within each behavioral caste. With this strategy, we could make sound statistical inference about gene expression differences within the nurse bee caste and within the forager bee caste, but not between the two behavioral castes since nurses and foragers were represented on different optical plates. Each sample was run in technical triplicates for target genes and reference gene actin by means of the delta–delta Ct method (Wang et al. 2012). Studies have shown that actin is one of the most stable gene expressed across different stages, tissues, and under stress condition (Lourenco et al. 2008; Scharlaken et al. 2008) and is often used as a single reference gene for expression studies in honey bee (Alaux et al. 2012; Ihle et al. 2015; Rueppell et al. 2017; Li et al. 2018). One sample was lost during the procedures, leading to the final sample sizes of N(urse)control = 16, NLPS = 15, NPGN = 16, F(orager)control = 16, FLPS = 16, and FPGN = 16. By monitoring negative control samples (without reverse transcriptase) and melting curve analysis, we verified that the RT-qPCR assays were not confounded by DNA contamination or primer dimers (Wang et al. 2012).

2.8 Statistical analyses

Survival data was processed with Statistica’s (Statistica 13, Dell Inc., Tulsa, USA) survival analysis tool. Specifically, survival curves were plotted using product-limited/Kaplan–Meier estimates. Multiple-sample group testing was based on an extension of Gehan’s as well as Peto and Peto’s generalized Wilcoxon test, and the log-rank test. This approach was followed by Bonferroni-corrected (threshold p < 0.003) post hoc Cox–Mantel pairwise comparisons between the treatment groups and for comparing survival between nurses and foragers independent of treatment. Post hoc Cox–Mantel multiple comparisons were also performed to contrast the three SSC colonies of the experiment to determine possible colony effects. An additional analysis with ANOVA was used to explore confounding variables. In the ANOVA, we included colony as an independent variable in addition to treatment.

For the gene expression analysis, ANOVA was used to test overall effects of treatment, followed by Tukey post hoc test for multiple comparison of gene expression between treatments. Tukey’s test takes multiple comparisons into account, and no further correction of the p values is required.

3 Results

3.1 Survival

None of the bees survived more than 72 h after treatment, which is consistent with a cost of immune system activation brought on by mechanical wounding during the injections of PBS, LPS, and PGN. Nonetheless, we detected an overall survival effect in the experiment (Kaplan–Meier, sample sizes N(urse)control = 68, NLPS = 75, NPGN = 61, F(orager)control = 67 FLPS = 70 FPGN = 79, df = 5, Chi2 = 96.77, p < 0.0001, Figure 1). Bonferroni-corrected pairwise comparison by post hoc Cox–Mantel test between groups (Online resource Table S2), however, suggested that this overall effect was specifically explained by worker caste, with nurses surviving differently than foragers.

The lifespan of honey bee workers after LPS, PGN, or control (PBS vehicle) injections. Nurse bees (N) survived significantly longer than forager bees (F) in general (Cox–Mantel, sample sizes Nurses = 204, Foragers = 216, U = 82.25, p < 0.0001). By comparing immunogen-treated bees with control-injected bees, we found that the challenge with immunogens did not affect survival significantly (statistics in Online resource Table S2).

No specific immunogen treatment generated a detectable survival effect as compared to the control. In contrast, post hoc comparison between nurses and foragers confirmed a significant effect of caste on survival (Cox–Mantel, sample sizes Nurses = 204, Foragers = 216, U = 82.25, p < 0.0001) with nurses surviving longest (Figure 1).

Our analysis of colony effects showed a significant survival difference between colonies (Cox–Mantel, sample sizes Colony1 = 140, Colony2 = 109, Colony3 = 171, df = 2, Chi2 = 19.54, p < 0.0001). Therefore, we used ANOVA to explore whether the lack of a treatment effect in the previous survival analysis might be due to variance from this confounding factor (colony). Reassuringly, ANOVA confirmed that treatment had no effect (ANOVA: F = 2.29, p = 0.10) while colony impacted survival significantly (ANOVA: F = 3.41, p = 0.03).

3.2 Gene expression in response to immune challenge

In nurse bees, expression of the AMP defensin-2 was significantly upregulated after immunogen injection (ANOVA, sample sizes N(urse)control = 16, NLPS = 15, NPGN = 16, p < 0.0001, Figure 2a). Post hoc testing revealed significant differences between all individual treatments on defensin-2 expression (Tukey: LPS vs control: p < 0.05, PGN vs control: p < 0.001, PGN vs LPS: p < 0.05). In contrast, we did not detect treatment effects on the AMP hymenoptaecin (ANOVA, sample sizes N(urse)control = 16, NLPS = 15, NPGN = 16, p = 0.1, Figure 2b) or on vg (ANOVA, sample sizes N(urse)control = 16, NLPS = 15, NPGN = 16, p = 0.92, Figure 2c).

Gene expression in nurse bees was calculated by delta–delta Ct method against the actin gene. Each bar present the mean ± SEM. Significant difference are denoted by different lowercase letters (a, b, c). a LPS and PGN injections resulted in upregulation of defensin-2. All treatment group where significantly different from each other (ANOVA, sample sizes N(urse)control = 16, NLPS = 15, NPGN = 16, p < 0.0001, Tukey’s post hoc test: LPS vs control: p < 0.05, PGN vs control: p < 0.001, PGN vs LPS: p < 0.05). b No significant changes in hymenoptaecin expression were detected in response to treatment (ANOVA, sample sizes N(urse)control = 16, NLPS = 15, NPGN = 16, p = 0.10). c No significant changes in vg expression were detected in response to treatment (ANOVA, sample sizes N(urse)control = 16, NLPS = 15, NPGN = 16, p = 0.92).

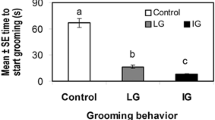

In forager bees, expression of defensin-2 (ANOVA, sample sizes F(orager)control = 16, FLPS = 16, FPGN = 16, p < 0.01, Figure 3a) and hymenoptaecin (ANOVA: F(orager)control = 16, FLPS = 16, FPGN = 16, p < 0.0001, Figure 3b) was significantly upregulated after immunogen treatment. Post hoc analysis revealed a treatment effect for the gene defensin-2 between PGN treated foragers compared to both LPS treated and control, but not between control and LPS injected workers (Tukey: PGN vs control: p = 0.0014, PGN vs LPS: p = 0.0125, LPS vs control: p = 0.71). Expression of hymenoptaecin was upregulated in both the PGN and LPS treatments compared to the control (Tukey: LPS vs control: p < 0.001, PGN vs control: p < 0.001, PGN vs LPS: p = 0.36). There was, however, no significant treatment effect on vg (ANOVA: F(orager)control = 16, FLPS = 16, FPGN = 16, p = 0.27, Figure 3c).

Gene expression in forager bees was calculated by delta–delta Ct method against the actin gene. Each bar present the mean ± SEM. Significant difference are denoted by different lowercase letters (a, b). a PGN challenge resulted in upregulation of defensin-2 compared to the control and LPS-treated foragers, while the LPS treatment did not differ from the control (ANOVA, sample sizes F(orager)control = 16, FLPS = 16, FPGN = 16, p < 0.01, Tukey: PGN vs control: p = 0.0014, PGN vs LPS: p = 0.0125, LPS vs control: p = 0.71). bHymenoptaecin was upregulated by PGN and LPS compared to control (ANOVA, sample sizes F(orager)control = 16, FLPS = 16, FPGN = 16, p < 0.0001, Tukey: LPS vs control: p < 0.001, PGN vs control: p < 0.001, PGN vs LPS: p = 0.36). cVg expression did not respond to treatment (ANOVA, sample sizes F(orager)control = 16, FLPS = 16, FPGN = 16, p = 0.27).

4 Discussion

In this study, we exposed same-aged nurse and forager honey bees to two immunogens and control injections with PBS (vehicle control). We observed that forager bees died sooner than nurses, independent of the immune challenge they were exposed to. In contrast, nurse and forager bees appeared to regulate their immune response differently, depending on whether they received LPS or PGN challenge. Our results expand on the general finding that immunogen treatments, as well as mechanical wounding, are stressful events that impact worker bees in survival tests (Nelson et al. 2007; Kohler et al. 2012). Explicitly, we expand the list of immunogens to include injection of PGN, and we show that these survival results are valid when contrasting same-aged nurses and foragers, which is a gold standard comparison in honey bee behavioral research. Yet, this standard may have some limitations relevant for experiments that include measurements of resilience or survival, because SCCs have a larger representation of precocious foragers and overaged nurses than normally age-structured colonies. These phenotypes might expose workers to elevated levels of physiological stress that could lead to susceptibilities and reduce lifespan (Guzmán-Novoa et al. 1994; Rueppell et al. 2007). A recent study identified survival rates comparable to ours when contrasting 21–23-day-old nurses and foragers in a SCC. Also, in their study, nurses survived significantly longer than foragers (Lourenco et al. 2019).

Our survival data and those of Lourenco et al. (2019) are consistent with previous research demonstrating that forager bees are generally more susceptible to stressors causing a shortened survival as compared to nurses (Rueppell et al. 2007; Speth et al. 2015). Immune activation is often viewed as a cost that trades off with survival (Li et al. 2018). Yet, in the frailer and resource-limited worker group, foragers, we did not observe that survival was further reduced in response to immunogen injection as compared to the vehicle control, which did not contain an immunogen. In our experiment overall, variation in nurse and forager survival was not explained by immunogen exposure (vs. control). A possible explanation for this outcome is that LPS and PGN are nonpathogenic, i.e., they do not actively infect bees, while at the same time, our control treatment involved mechanical wounding which is an established (non-infections) protocol of immune challenge in bees (Bordier and others 2016). Thereby, our results are in accordance with previous studies that did not find specific survival differences in experiments involving LPS-treated honey bees (Richard et al. 2008; Alaux et al. 2012; Kazlauskas et al. 2016).

While survival effects may differ in tests with active and non-pathogenic immunogens, previous studies corroborate that AMP production and expression of immune-related genes can be affected by LPS injection (Richard et al. 2008; Alaux et al. 2012). We found different transcription patterns in nurse and forager bees for defensin-2 and hymenoptaecin. PGN upregulated defensin-2 in both nurses and foragers, while LPS upregulate defensin-2 in nurses only. Forager upregulated hymenoptaecin in response to both LPS and PGN, while the expression of hymenoptaecin was unchanged in nurses. Consequently, our results indicate that nurse and forager honey bees regulate expression of immune related genes differently. Defensin-2 and hymenoptaecin are proposed to be downstream genes of the Toll pathway and IMD pathway, respectively (Evans et al. 2006), suggesting different acute pathway activation in these two behavioral castes of workers. Data from the PBS-injected control group supports this conclusion. Injections with PBS are sufficient to activate the immune system, and thereby, we reveal antigen-specific effects when contrasting the control to the LPS and PGN treatments. In other words, the antigen-specific effects in worker bees appear to go beyond a general response to mechanical wounding.

In this study, we did not detect an up- or downregulation of the vg gene when measuring expression 8 h after injection of immunogens vs. PBS control. It is possible that vg mRNA levels are consistently changed in either direction by all the three challenges, or alternatively, none of these manipulations impact vg. A previous experiment showed that PBS injections can upregulate vg expression compared to non-injected bees (Salmela et al. 2015), while a different experiment showed that vg is downregulated after a “pin prick” challenge (mechanical wounding, Bordier and others 2016). Future experiment should use time-series with multiple treatment groups and including non-injected controls to resolve possible dynamic patterns in the response of vg to different immune challenges.

References

Alaux, C., N. Kemper, A. Kretzschmar and Y. Le Conte (2012). Brain, physiological and behavioral modulation induced by immune stimulation in honeybees (Apis mellifera): A potential mediator of social immunity? Brain Behavior and Immunity 26(7): 1057–1060.

Amdam, G. V., A. Aase, S. C. Seehuus, M. K. Fondrk, K. Norberg and K. Hartfelder (2005). Social reversal of immunosenescence in honey bee workers. Experimental Gerontology 40(12): 939–947.

Behrends, A., R. Scheiner, N. Baker and G. V. Amdam (2007). Cognitive aging is linked to social role in honey bees (Apis mellifera). Experimental Gerontology 42(12): 1146–1153.

Bordier, C., S. Suchail, M. Pioz, J. M. Devaud, C. Collet, M. Charreton, Y. Le Conte and C. Alaux (2017). Stress response in honeybees is associated with changes in task-related physiology and energetic metabolism. J Insect Physiol 98: 47–54.

Evans, J. D., K. Aronstein, Y. P. Chen, C. Hetru, J. L. Imler, H. Jiang, M. Kanost, G. J. Thompson, Z. Zou and D. Hultmark (2006). Immune pathways and defence mechanisms in honey bees Apis mellifera. Insect Molecular Biology 15(5): 645–656.

Fluri, P., H. Wille, L. Gerig and M. Lüscher (1977). Juvenile hormone, vitellogenin and haemocyte composition in winter worker honeybees (Apis mellifera). Experientia 33(9): 1240–1241.

Guzmán-Novoa, E., R. E. Page and N. E. Gary (1994). Behavioral and life-history components of division of labor in honey bees (Apis mellifera L.). Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology 34(6): 117–409.

Hillyer, J. F. (2016). Insect immunology and hematopoiesis. Dev Comp Immunol 58: 102–118.

Huang, Z. Y. and G. E. Robinson (1992). Honeybee colony integration: worker-worker interactions mediate hormonally regulated plasticity in division of labor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 89(24): 11726–11729.

Ihle, K. E., O. Rueppell, Z. Y. Huang, Y. Wang, M. K. Fondrk, R. E. Page, Jr. and G. V. Amdam (2015). Genetic architecture of a hormonal response to gene knockdown in honey bees. J Hered 106(2): 155–165.

Kazlauskas, N., M. Klappenbach, A. M. Depino and F. F. Locatelli (2016). Sickness Behavior in Honey Bees. Frontiers in Physiology 7: 10.

Kohler, A., C. W. W. Pirk and S. W. Nicolson (2012). Simultaneous stressors: Interactive effects of an immune challenge and dietary toxin can be detrimental to honeybees. Journal of Insect Physiology 58(7): 918–923.

Laughton, A. M., M. Boots and M. T. Siva-Jothy (2011). The ontogeny of immunity in the honey bee, Apis mellifera L. following an immune challenge. Journal of Insect Physiology 57(7): 1023–1032.

Li, W., Y. Chen and S. C. Cook (2018). Chronic Nosema ceranae infection inflicts comprehensive and persistent immunosuppression and accelerated lipid loss in host Apis mellifera honey bees. Int J Parasitol 48(6): 433–444.

Lourenco, A. P., K. R. Guidugli-Lazzarini, F. C. P. Freitas, M. M. G. Bitondi and Z. L. P. Simoes (2013). Bacterial infection activates the immune system response and dysregulates microRNA expression in honey bees. Insect Biochemistry and Molecular Biology 43(5): 474–482.

Lourenco, A. P., A. Mackert, A. D. Cristino and Z. L. P. Simoes (2008). Validation of reference genes for gene expression studies in the honey bee, Apis mellifera, by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. Apidologie 39(3): 372-U333.

Lourenco, A. P., J. R. Martins, F. A. S. Torres, A. Mackert, L. R. Aguiar, K. Hartfelder, M. M. G. Bitondi and Z. L. P. Simoes (2019). Immunosenescence in honey bees (Apis mellifera L.) is caused by intrinsic senescence and behavioral physiology. Exp Gerontol 119: 174–183.

Munch, D., N. Baker, E. M. K. Rasmussen, A. K. Shah, C. D. Kreibich, L. E. Heidem and G. V. Amdam (2013). Obtaining Specimens with Slowed, Accelerated and Reversed Aging in the Honey Bee Model. Jove-Journal of Visualized Experiments(78).

Münch, D. and G. V. Amdam (2013). Brain Aging and Performance Plasticity in Honeybees. Handbook of Behavioral Neuroscience 22: 487–500.

Nelson, C. M., K. E. Ihle, M. K. Fondrk, R. E. Page and G. V. Amdam (2007). The gene vitellogenin has multiple coordinating effects on social organization. PLoS Biol 5(3): e62.

Richard, F. J., A. Aubert and C. M. Grozinger (2008). Modulation of social interactions by immune stimulation in honey bee, Apis mellifera, workers. Bmc Biology 6.

Rueppell, O., C. Bachelier, M. K. Fondrk and R. E. Page (2007). Regulation of life history determines lifespan of worker honey bees (Apis mellifera L.). Experimental Gerontology 42(10): 1020–1032.

Rueppell, O., B. Yousefi, J. Collazo and D. Smith (2017). Early life stress affects mortality rate more than social behavior, gene expression or oxidative damage in honey bee workers. Exp Gerontol 90: 19–25.

Salmela, H., G. V. Amdam and D. Freitak (2015). Transfer of Immunity from Mother to Offspring Is Mediated via Egg-Yolk Protein Vitellogenin. Plos Pathogens 11(7): 12.

Scharlaken, B., D. C. de Graaf, K. Goossens, M. Brunain, L. J. Peelman and F. J. Jacobs (2008). Reference gene selection for insect expression studies using quantitative real-time PCR: The head of the honeybee, Apis mellifera, after a bacterial challenge. Journal of Insect Science 8.

Schmid, M. R., A. Brockmann, C. W. W. Pirk, D. W. Stanley and J. Tautz (2008). Adult honeybees (Apis mellifera L.) abandon hemocytic, but not phenoloxidase-based immunity. Journal of Insect Physiology 54(2): 439–444.

Seehuus, S. C., K. Norberg, U. Gimsa, T. Krekling and G. V. Amdam (2006). Reproductive protein protects functionally sterile honey bee workers from oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103(4): 962–967.

Seeley, T. D. (1995). The wisdom of the hive : the social physiology of honey bee colonies. Cambridge, Mass., Harvard University Press.

Speth, M. T., C. D. Kreibich, G. V. Amdam and D. Munch (2015). Aging- and task-related resilience decline is linked to food responsiveness in highly social honey bees. Exp Gerontol 65: 46–52.

Wang, Y., C. S. Brent, E. Fennern and G. V. Amdam (2012). Gustatory perception and fat body energy metabolism are jointly affected by vitellogenin and juvenile hormone in honey bees. PLoS Genet 8(6): e1002779.

Wilson-Rich, N., S. T. Dres and P. T. Starks (2008). The ontogeny of immunity: Development of innate immune strength in the honey bee (Apis mellifera). Journal of Insect Physiology 54(10–11): 1392–1399.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nick Baker for managing the colonies. We thank Claus Kreibich for valuable input. We thank Jane Ludvigsen for reading and commenting on the text.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

EMHB, HS, GVA: designed the study, analyzed the data; EMHB, HS, AV, YW: performed research; EMHB, DM, GVA drafted the paper. All authors provided text, read, and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interests

The authors declare that they have no potential conflict of interest in relation to the study in this paper.

Additional information

Handling editor: Marina Meixner

Différentes activations des gènes liés au système immunitaire chez les nourrices et butineuses ( Apis mellifera )

Abeille / vieillissement / activation immunitaire / vitellogénine / défensine-2

Differentielle Aktivierung von Genen des Immunsystems bei Pflegebienen und Sammlerinnen der Honigbiene ( Apis mellifera )

Honigbiene / Altern / Immunsystemaktivierung / Vitellogenin / Defensin-2

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Byhrø, E.M.H., Salmela, H., Vitlic, A. et al. Different activation of immune-related genes in honey bee nurses and foragers (Apis mellifera). Apidologie 50, 463–471 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-019-00658-z

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-019-00658-z