Abstract

This study estimated the toxicity of the insecticides chlorpyrifos and phosmet to the stingless bees Scaptotrigona bipunctata and Tetragonisca fiebrigi. The results showed significant differences in susceptibility between the tested species, indicating that S. bipunctata are more tolerant to chlorpyrifos than T. fiebrigi in both assays. In contrast, the two tested stingless bee species showed no significant differences in susceptibility to phosmet. Our findings indicated that the insecticides chlorpyrifos and phosmet are potentially dangerous to S. bipunctata and T. fiebrigi both topically and by ingestion. It is essential to propose measures to minimize the impact of these products on pollinators. This study is the first evaluation of the lethal effects of the insecticides chlorpyrifos and phosmet to S. bipunctata and T. fiebrigi, and it provides important support for future studies on pesticide toxicity in stingless bees.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Pollination is an environmental service essential for the maintenance of natural ecosystems and agriculture (Costanza et al. 1997; Ricketts et al. 2008). Approximately 85% of angiosperm species are pollinated by animals (Ollerton et al. 2011). Bees are considered the most efficient pollinators (Potts et al. 2010) and are responsible for pollinating approximately 70% of cultured plant species (Ricketts et al. 2008).

The current decline in diversity and abundance of pollinators has raised concerns (Dively and Kamel 2012) regarding the future sustainability of pollination services (Biesmeijer et al. 2006).

Factors such as habitat fragmentation, loss of native vegetation and climate change are ongoing contributors to reductions in bee populations (Freitas et al. 2009). However, the unsustainable use of agricultural ecosystems and the excessive use of pesticides are considered the leading causes of bee diversity losses (Wiest et al. 2011; Nicholls and Altieri 2013; Sanchez-Bayo and Goka 2014).

Within this context, pesticide applications on crops that produce bee-attracting flowers should be considered in studies of hazards to pollinator species. In Brazil, bee pollination services are critically important to several crops, including apples, coffee, cotton, oranges and soybeans (Imperatriz-Fonseca 2004).

Cultivating these crops involves applying a wide range of pesticides for disease and pest control (Rocha 2012). Of particular importance in this context are organophosphate pesticides such as chlorpyrifos and phosmet. These insecticides have a broad action spectrum and are highly toxic and damaging to the environment, including to non-target insect species (Cutler et al. 2014). Chlorpyrifos and phosmet are neurotoxic insecticides that act by inhibiting acetylcholinesterase, an enzyme essential to the transmission of nerve impulses (Silva et al. 2015).

Due to its global importance as a pollinator, Apis mellifera L. is the species most often used as a model organism in studies of non-target insect toxicity (Brittain and Potts 2011). However, it is well known that different bee species are differentially susceptible to insecticides (Alston et al. 2007). Therefore, evaluation of pesticide toxicity in other bee taxa should be considered. The stingless bees (Meliponini) have biological characteristics conducive for use in managed pollination (Venturieri et al. 2011) and are gradually being recognized as alternatives for commercial pollination operations in tropical and subtropical regions (Slaa et al. 2006). Nevertheless, there has been little research into their susceptibility to pesticides (Santos et al. 2016).

Scaptotrigona bipunctata (Lepeletier) and Tetragonisca fiebrigi (Schwarz) are among the most commonly kept Meliponini species in three Brazilian biomes (Pampas, Atlantic Rainforest and Pantanal). S. bipunctata, popularly known as the tubuna, is found in Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay and Peru, where it forms large nests with massive honey output capacity. T. fiebrigi, known as the jataí, is found in parts of Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil and Paraguay, is easily managed and is highly regarded as an excellent honey producer (Venturieri et al. 2011; Camargo and Pedro 2013).

In view of the widespread use of organophosphate insecticides on bee-attractive crops in Brazil and the consequent risk to non-target organisms, as well as the large geographic range of S. bipunctata and T. fiebrigi, the present study sought to determine the median lethal concentration (LC50) for oral exposure and the median lethal dose (LD50) for topical exposure of S. bipunctata and T. fiebrigi of foragers to the insecticides chlorpyrifos and phosmet.

2 Material and methods

The bees used in this study were obtained from S. bipunctata and T. fiebrigi colonies kept at the Meliponary of the Pontifícia Universidade Católica do Rio Grande do Sul (PUCRS) (Porto Alegre, RS, Brazil, 30° 3′ S, 51° 10 W).

Sixty bees from each species were used for each exposure (dose/concentration) and its respective controls. For tests on S. bipunctata, each treatment consisted of five replicates with 12 bees in each replicate. For tests on T. fiebrigi, each treatment consisted of three replicates with 20 bees in each replicate. To maintain equivalent confinement conditions, the distribution of the number of bees in each box was determined by considering the size and behaviour of the individuals of the two species. To ensure genetic variability and obtain more reliable toxicological estimates, each replicate consisted of bees from different colonies.

For the oral exposure tests, bees were collected near the entrance to each colony and transferred to wooden cages (9.5 × 11.5 × 2.5 cm). For the topical tests, the bees were transferred to Petri dishes (150 × 15 mm) lined with filter paper.

To minimize the stress of confinement, before testing, the bees were allowed to adapt for 24 h, during which time they were fed a sucrose solution containing no insecticide. During the adaptation and experimental periods, the bees were maintained in a chamber of biochemical oxygen demand (BOD) at 28 ± 2°C and 70 ± 2% RH.

The insecticides used were commercially available products: chlorpyrifos (Lorsban® 480BR, Dow AgroSciences, 48% active ingredient (a.i.)) and phosmet (Imidan® 500wp, Cross Link, 50% a.i.) (MAPA 2015).

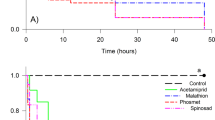

The susceptibility of bee foragers to each insecticide was tested via two routes of exposure: oral and topical. Both trials were conducted in accordance with the international guidelines for pesticide toxicity testing in honeybees (OECD 1998a, b). To determine the appropriate concentrations for the formal test, preliminary bioassays were performed with ten serial dilutions of the stock solution at a factor of 10 (1 μg a.i./μL of distilled water) following Medrzycki et al. (2013). Second, a series of five concentrations (with a factor not exceeding 2) was established to cover the mortality range of 1 to 100% in relation to the slope of the toxicity curve (OECD 1998a, b). To ascertain the median lethal concentration (LC50) for oral assays and median lethal dose (LD50) for topical assays, mortality rates were recorded after 48 h of exposure to each insecticide. Bees that remained immobile for more than 10 s were considered dead.

2.1 Acute oral toxicity

For the acute oral toxicity assays, a stock solution of pesticide was diluted in sucrose solution (sucrose/water 1:1) to the five desired concentrations. The chlorpyrifos concentrations ranged from 0.0025 to 0.0400 μg a.i./μL diet for S. bipunctata and 0.0010 to 0.0050 μg a.i./μL diet for T. fiebrigi. The phosmet concentrations ranged from 0.0050 to 0.1000 μg a.i./μL diet for S. bipunctata and 0.0050 to 0.0667 μg a.i./μL diet for T. fiebrigi. The control group received a sucrose solution with no added insecticide.

To induce consumption of the solutions, bees were starved for 2 h before the start of the experiments. Subsequently, each group of bees was allowed access to 100 μL of treated food. Six hours later, the feeder was replaced with one containing a sucrose-only solution. The amount of food consumed was calculated by weighing the feeders before and after exposure.

2.2 Acute topical toxicity

For the acute topical toxicity assays, the stock solution of pesticide was diluted with acetone to the five desired doses. For chlorpyrifos, the doses ranged from 0.0025 to 0.0400 μg a.i./bee and 0.0013 to 0.0100 μg a.i./bee for S. bipunctata and T. fiebrigi, respectively. For phosmet, the dosage ranged from 0.0025 to 0.0400 μg a.i./bee regardless of species.

Prior to topical application, the bees were anaesthetised at −8°C for 2 min. Then, a micropipette was used to apply 1 μL of each dose to the pronotum area of each bee. Two control groups were used: a solvent control group, which received acetone alone, and an unexposed control group, to which no substances were applied. After exposure, bees were kept in BOD with access to food (sucrose solution) ad libitum.

2.3 Statistical analyses

LC50 and LD50 values and their respective 95% confidence intervals and chi-square test statistics were determined with the “two-parameter log-logistic function” of the “drc” package in the Analysis of Dose-Response Curves (Ritz and Streibig 2005), compiled in the R software environment (2015). The trimmed Spearman–Karber method was used for nonparametric data (Hamilton et al. 1977).

After calculating the LC50 and LD50, the toxicity of the tested insecticides could be evaluated by two methods: (I) comparison of the LC50 or LD50 of each insecticide between the two bee species, and (II) comparison of the LC50 or LD50 of both insecticides within each bee species. In both cases, the confidence intervals for LC50 and LD50 were considered for analysis and were deemed significantly different when there was no overlap between the intervals at the 95% likelihood level.

Analysis of variance (one- and two-way ANOVAs) with Tukey’s post hoc tests were used to assess the differences between bees that consumed food containing pesticide and their respective controls (bees that consumed food without pesticide) during the oral exposure assays. Furthermore, the results of the solvent control assays were analysed using chi-square tests to assess the toxicity of acetone to S. bipunctata and T. fiebrigi foragers.

3 Results

3.1 Acute oral toxicity

The LC50 of chlorpyrifos was 0.0112 μg a.i./μL diet in S. bipunctata and 0.0018 μg a.i./μL diet in T. fiebrigi. Thus, the toxicity of this insecticide differed significantly between the two species, with T. fiebrigi foragers exhibiting markedly greater susceptibility to its intake compared with S. bipunctata. These significant differences in LC50 were made evident by the absence of overlap between confidence intervals (Table I).

The LC50 of phosmet was 0.0245 μg a.i./μL diet in S. bipunctata and 0.0236 μg a.i./μL diet in T. fiebrigi. The overlap in confidence intervals suggests there was no significant difference in susceptibility to this insecticide between S. bipunctata and T. fiebrigi (Table I).

Of the organophosphate insecticides tested, chlorpyrifos was significantly more toxic to both bee species, as demonstrated by the absence of overlap between confidence intervals (Table I).

The amount of diet consumed did not differ significantly among the groups with different pesticide concentrations and their respective controls (sucrose without pesticide) (S. bipunctata: chlorpyrifos: F = 2.974, P = 0.032, Tukey, P = 0.081; phosmet: F = 0.237, P = 0.942; T. fiebrigi: chlorpyrifos: F = 0.864, P = 0.533; phosmet: F = 1.990, P = 0.153). There was no difference in the diet intake between the insecticides tested or in the interactions between species and pesticides (F = 1.158, P = 0.285; F = 0.002, P = 0.966, respectively).

3.2 Acute topical toxicity

In acute topical toxicity assays, the LD50 of chlorpyrifos was 0.0110 μg a.i./bee for S. bipunctata and 0.0033 μg a.i./bee for T. fiebrigi.

The LD50 of phosmet was 0.0087 μg a.i./bee for S. bipunctata and 0.0083 μg a.i./bee for T. fiebrigi.

According to the LD50 confidence intervals, there were significant differences in the susceptibility of the two tested bee species to topically applied chlorpyrifos, with S. bipunctata foragers exhibiting greater tolerance than T. fiebrigi foragers. However, the overlap in confidence intervals suggests there was no significant difference between S. bipunctata and T. fiebrigi in terms of susceptibility to phosmet (Table II).

There was no significant difference between chlorpyrifos and phosmet in terms of toxicity to S. bipunctata, as demonstrated by the overlap in confidence intervals. However, chlorpyrifos was more toxic to T. fiebrigi than was phosmet when both were applied topically (Table II).

Assays performed with the solvent control group (bees topically treated with acetone) failed to show any significant difference in mortality compared to the unexposed control group (χ 2 = 1.200, P = 0.273).

4 Discussion

Two routes of exposure (oral and topical) were used to assess the acute toxicity responses to chlorpyrifos and phosmet in this study. This is justified because when bees forage in pesticide-treated areas, these products may be absorbed orally through intake of pollen and nectar containing residual insecticide, or exposure can occur topically when chemicals suspended in the air come into contact with the bee’s body (Johnson et al. 2010; Mullin et al. 2010).

Toxicity via the oral route is possible, as many studies have reported the presence of chlorpyrifos and phosmet residue in the pollen and nectar of treated plants as well as in honey and pollen stored (Wiest et al. 2011; Stoner and Eitzer 2013; Silva et al. 2015).

In the present study, S. bipunctata were more tolerant to chlorpyrifos via oral exposure than T. fiebrigi. However, the susceptibility of the two bee species to phosmet did not differ significantly. Differences in susceptibility between species may also be related to differential detoxification capacities. When the route of exposure is through ingestion of contaminated pollen or nectar, toxicity can be reduced through detoxification processes that occur mainly in the midgut and fat body (Yu et al. 1984).

Chlorpyrifos had the lowest LC50 values and was thus considered the most toxic of the two insecticides to both bee species. Overall, organophosphate insecticides have relatively low toxicity through oral exposure because they are rapidly metabolized or otherwise cleared; however, persistent compounds such as chlorpyrifos may remain in the body long enough to cause toxicity when ingested (Sanchez-Bayo and Goka 2014). Using this logic, Sanchez-Bayo and Goka (2014) report that chlorpyrifos ingestion may pose a hazard to A. mellifera because of its high toxicity and the large amount of residue found in pollen and honey.

Regarding diet, no statistically significant differences were found in the bees’ consumption of food treated with either chlorpyrifos or phosmet in either bee species; even the highest concentrations had no repellent effect during the oral toxicity assays. Kessler et al. (2015) carried out food preference experiments and found that A. mellifera and Bombus terrestris L. do not avoid foods containing neonicotinoid insecticides (imidacloprid, thiamethoxam and clothianidin) and that bees actually consumed more of the sucrose solutions containing imidacloprid and thiamethoxam than they did of the sucrose solutions without insecticide.

According to the LD50 values obtained in our topical exposure assays, both chlorpyrifos and phosmet would be classified as highly toxic to bees (LD50 <2.0 μg a.i./bee) (Atkins et al. 1981).

In S. bipunctata, topical exposure testing did not reveal significant differences in toxicity between chlorpyrifos and phosmet. This result is similar to that found by Kanga and Somorin (2012) in a comparison of the effect of these two insecticides on adult Aethina tumida Murray (Coleoptera: Nitidulidae).

In T. fiebrigi, topical chlorpyrifos was more toxic than phosmet. This may be associated with the lipophilic structure of this compound and the lipid composition of the bee cuticle (Bacci et al. 2006). Lipophilic compounds exhibit greater affinity for the cuticle and are thus more easily absorbed and readily transported to their target site of action (Leite et al. 1998). This hypothesis is based on the low water solubility of chlorpyrifos (1.05 mg/L at 20°C) compared to phosmet (24.4 mg/L at 20°C). Compounds that are more lipophilic (i.e. less soluble in water) are able to penetrate more readily through the cuticle (Milhome et al. 2009; INECC 2012).

A comparison of our results to the established LD50 in A. mellifera shows that the LD50 values for A. mellifera were significantly higher than those calculated for S. bipunctata and T. fiebrigi. The calculated LD50 (topical) in A. mellifera is 0.11 μg/bee for chlorpyrifos and 1.13 μg/bee for phosmet (Sylvia 2010). Therefore, A. mellifera is approximately 33 times more tolerant to chlorpyrifos and up to 136 times more tolerant to phosmet than is T. fiebrigi, which demonstrates the high toxicity of the tested insecticides to these stingless bees.

Comparing the toxicity of each insecticide by exposure route (oral vs. topical), we found differences in susceptibility between species. S. bipunctata foragers did not exhibit a significant difference in susceptibility to chlorpyrifos between oral and topical exposure. Conversely, in T. fiebrigi, this insecticide was more toxic when administered orally. These findings differ from those reported by Suchail et al. (2000) for A. mellifera, in which chlorpyrifos was four times more toxic when applied by contact than when ingested (LD50 topical = 59 ng/bee; LD50 oral = 250 ng/bee). These differences may be a result of morphological and physiological differences between bee species or of methodological heterogeneity across studies.

Unlike chlorpyrifos, phosmet was more toxic to both bee species when administered topically than when ingested via oral exposure. This difference in toxicity is related to the modes of action of the tested insecticides (Stevenson 1978; Devillers 2003). While chlorpyrifos has contact, oral and fumigant action (Fletcher and Barnett 2003), phosmet has a greater toxic effect on contact (Kovaleski and Ribeiro 2003). In a study of the effects of phosmet on the solitary bee Megachile rotundata (Fabricius), Gradish et al. (2012) found that phosmet is highly toxic when applied topically.

Our results showed significant differences in susceptibility between the two evaluated bee species, with T. fiebrigi being more susceptible to chlorpyrifos than S. bipunctata. These differences in susceptibility have been attributed to interspecies differences of specific characteristics (Brittain and Potts 2011; Del Sarto et al. 2014) including body weight, detoxification capacity and cuticle chemical composition and thickness (Yu 1987; Oliveira et al. 2002; Bacci et al. 2006; Tomé et al. 2017).

It is important to note that pesticide toxicity in laboratory tests may diverge from toxicity observed in the field (Devillers 2003). Assays performed under laboratory conditions often overestimate the lethal effects of insecticides in the natural environment (Lourenço et al. 2012). Furthermore, susceptibility in agricultural areas depends on other circumstances, including abiotic factors, pesticide degradation rates and bee behaviours (Gradish et al. 2012). Nevertheless, Stevenson (1978) noted that a correlation exists between the relative toxicity determined on laboratory testing and the actual effects of pesticides on bees in the field.

The results of this study indicate that chlorpyrifos and phosmet are hazardous to bee health; therefore, it is essential to propose measures to minimize the impact of pesticides on pollinators. Preserving any remaining semi-natural woodland or wild vegetation near crop farming areas, identifying and using insecticides with lower toxicity, using integrated pest management approaches, avoiding applications during crop-blooming periods and protecting colonies whenever possible are relevant interventions that can be implemented to mitigate the impact of organophosphate spraying on bees (Pinheiro and Freitas 2010; Rocha 2012).

Furthermore, Roubos et al. (2014) reported that the negative impacts of insecticides can be reduced when these chemicals are applied directly to the soil. Morales-Rodriguez and Peck (2009) noted that synergistic combinations of biological and chemical insecticides may be promising alternatives for pest control. In addition, Xavier et al. (2010) suggested using botanical insecticides as an alternative because those were not associated with adverse effects on stingless bees in their study. Brown et al. 2016, mentioned actions to mitigate the negative impacts of pesticides through new laws implementing chronic and sublethal trials, as well as field trials with different species of pollinators before the release of new pesticides. Through good agricultural practises, the environment, the profitability of agriculture and food safety will all benefit (Nocelli et al. 2011; Goulson et al. 2015; Kessler et al. 2015).

The differences in susceptibility between the tested stingless bees and A. mellifera highlight the importance of including other bee species in the toxicity assays required for pesticide registration to ensure that native bees are protected (Decourtye et al. 2013; Arena and Sgolastra 2014). Thus, we suggest that new analyses of the lethal and sublethal effects of pesticides recommended for use in bee-attracting crops be carried out on stingless bee species through both field and semi-field experiments with a view toward ensuring the preservation of biodiversity, the safety of native bee species and the sustainability of pollination services.

References

Alston, D.G., Tepedino, V.J., Bradley, B.A., Toler, T.R., Griswold, T. L., Messinger, S. M. (2007) Effects of the insecticide phosmet on solitary bee foraging and nesting in orchards of Capitol Reef National Park, Utah. Environ. Entomol. 36(4), 811–816

Arena, M., Sgolastra, F. (2014) A meta-analysis comparing the sensitivity of bees to pesticides. Ecotoxicology 23(3), 324–334

Atkins, E.L., Kellum, D. Atkins, K.W. (1981) Reducing pesticide hazards to honey bees: mortality prediction techniques and integrated management strategies. Leaflet-University of California, Cooperative Extension Service, USA.

Bacci, L., Pereira, E.J., Fernandes, F.L., Picanço, M.C., Crespo, A.L.B., Campos, M.R. (2006). Seletividade fisiológica de inseticidas a vespas predadoras (Hymenoptera: Vespidae) de Leucoptera coffeella (Lepidoptera: Lyonetiidae). BioAssay 1(10), 1–7

Biesmeijer, J.C., Roberts, S.P.M., Reemer, M., Ohlemüller, R., Edwards, M., et al. (2006) Parallel declines in pollinators and insect-pollinated plants in Britain and the Netherlands. Science 313(5785), 351–354

Brittain, C., Potts, S.G. (2011) The potential impacts of insecticides on the life-history traits of bees and the consequences for pollination. Basic Appl. Ecol. 12(4), 321–331

Brown, M.J., Dicks, L.V., Paxton, R.J., Baldock, K.C., Barron, A.B., et al (2016). A horizon scan of future threats and opportunities for pollinators and pollination. PeerJ 4, e2249, DOI:10.7717/peerj.2249

Camargo, J. M. F., Pedro, S.R.M. (2013) Meliponini Lepeletier, 1836, in: Moure, J.S., Urban, D., Melo, G.A.R. (Orgs.), Catalogue of bees (Hymenoptera, Apoidea) in the Neotropical Region. http://www.moure.cria.org.br/catalogue [Accessed 12 Oct 13]

Costanza, R., D’Arge, R., Groot, R., Farber, S., Grasso, M., et al. (1997) The value of the world’s ecosystem services and natural capital. Nature 387, 253–260

Cutler, G.C., Purdy, J., Giesy, J.P., Solomon, K.R. (2014) Risk to pollinators from the use of chlorpyrifos in the United States, in: Giesy, J.P. e Solomon, K.R. (Eds.), Ecological risk assessment for chlorpyrifos in terrestrial and aquatic systems in the United States, Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 231, 219–265

Decourtye, A., Henry, M., Desneux, N. (2013) Overhaul pesticide testing on bees. Nature 497(7448), 188

Del Sarto, M.C.L., Oliveira, E.E., Guedes, R.N.C., Campos, L.A.O. (2014) Differential insecticide susceptibility of the Neotropical stingless bee Melipona quadrifasciata and the honey bee Apis mellifera. Apidologie 45(5), 626–636

Devillers, J. (2003) Acute toxicity of pesticides to honey bees, in: Devillers, J. e Pham-Delègue, M.H. (Eds.), Honey bees: estimating the environmental impact of chemicals. Taylor & Francis e-Library, pp. 56–66

Dively, G.P., Kamel, A. (2012) Insecticide residues in pollen and nectar of a cucurbit crop and their potential exposure to pollinators. J. Agric. Food Chem. 60(18), 4449–4456

Fletcher, M., Barnett, L. (2003) Bee pesticide poisoning incidents in the United Kingdom. Bull. Insectology 56(1), 141–145

Freitas, B.M., Imperatriz-Fonseca, V.L., Medina, L.M., Kleinert, A.D.M.P., Galetto, L., Nates-Parra, G., Quezada-Euán, J.J.G. (2009) Diversity, threats and conservation of native bees in the Neotropics. Apidologie 40(3), 332–346

Goulson, D., Nicholls, E., Botías, C., Rotheray, E.L. (2015) Bee declines driven by combined stress from parasites, pesticides, and lack of flowers. Science 347(6229), 1255957

Gradish, A.E., Scott-Dupree, C.D., Cutler, G.C. (2012) Susceptibility of Megachile rotundata to insecticides used in wild blueberry production in Atlantic Canada. J. Pest. Sci. 85, 133–140

Hamilton, M.A., Russo, R.C., Thurston, R.V. (1977) Trimmed Spearman-Karber method for estimating median lethal concentrations in toxicity bioassays. Environ. Sci. Technol. 11(7), 714–719

Imperatriz-Fonseca, V.L. (2004) Serviços aos ecossistemas, com ênfase nos polinizadores e polinização. http://www.ib.usp.br/vinces/logo/servicosaosecossistemas_polinizadores_vera.pdf [Accessed 10 Oct 13]

INNEC-INSTITUTO NACIONAL DE ECOLOGÍA Y CAMBIO CLIMÁTICO (2012) Fosmet – datos de identificación http://www2.inecc.gob.mx/sistemas/plaguicidas/pdf/fosmet.pdf [Accessed 12 Jun 13]

Johnson, R.M., Ellis, M.D., Mullin, C.A., Frazier, M. (2010) Pesticides and honey bee toxicity – USA. Apidologie 41(3), 312–331

Kanga, L.H., Somorin, A.B. (2012) Susceptibility of the small hive beetle, Aethina tumida (Coleoptera: Nitidulidae), to insecticides and insect growth regulators. Apidologie 43(1), 95–102

Kessler, S.C., Tiedeken, E.J., Simcock, K.L., Derveau, S., Mitchell, J., Softley, S., Stout, J.C., Wright, G.A. (2015). Bees prefer foods containing neonicotinoid pesticides. Nature 521(7550), 74–76

Kovaleski, A., Ribeiro, L.G (2003) Manejo de Pragas na Produção Integrada de Maçã, In: Protas, J.F.DaS., Sanhueza, R.M.V. Produção integrada de frutas: o caso da maçã no Brasil. Bento Gonçalves: Embrapa Uva e Vinho, pp. 61–68

Leite, G.L.D., Picanco, M., Guedes, R.N.C., Gusmão, M.R. (1998). Selectivity of insecticides with and without mineral oil to Brachygastra lecheguana (Hymenoptera: Vespidae), a predator of Tuta absoluta (Lepidoptera: Gelechiidae). Ceiba 39(2), 191–194

Lourenço, C.T., Carvalho, S.M., Malaspina, O., Nocelli, R.C.F. (2012) Oral toxicity of fipronil insecticide against the stingless bee Melipona scutellaris (Latreille, 1811). Bull. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 89(4), 921–924

MAPA-Ministério da Agricultura, Pecuária e Abastecimento (2015). AGROFIT: Sistemas de Agrotóxicos Fitossanitários. http://extranet.agricultura.gov.br/agrofit_cons/principal_agrofit_cons [Accessed 10 Oct 13]

Medrzycki, P., Giffard, H., Aupinel, P., Belzunces, L.P., Chauzat, M-P., et al. (2013) Standard methods for toxicology research in Apis mellifera. J. Apic. Res. 52(4), 1–60

Milhome, M.A.L., Sousa, D.O.B., Lima, F.D.A., Nascimento, R.D. (2009). Avaliação do potencial de contaminação de águas superficiais e subterrâneas por pesticidas aplicados na agricultura do Baixo Jaguaribe, CE. Eng. Sanit. Ambient. 14(3), 363–372

Morales-Rodriguez, A., Peck, D.C. (2009) Synergies between biological and neonicotinoid insecticides for the curative control of the white grubs Amphimallon majale and Popillia japonica. Biol. Control 51(1), 169–180

Mullin, C.A., Frazier, M., Frazier, J., Ashcraft, S., Simonds, R., vanEngelsdorp, D., Pettis, J. S. (2010) High levels of miticides and agrochemicals in North American apiaries: Implications for honey bee health. PLoS ONE 5(3), e9754, DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0009754

Nicholls, C.I., Altieri, M.A. (2013) Plant biodiveresity enhances bees and other insect pollinators in agroecosystems. A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 33(2), 257–274

Nocelli, R.C.F., Malaspina, O., Carvalho, S.M., Lourenço, C.T., Roat, T.C., Pereira, A.M., Silva-Zacarin, E.C.M (2011) As abelhas e os defensivos agrícolas, in: Imperatriz-Fonseca, V.L., Canhos, D.A.L., Saraiva, A.M., Polinizadores no Brasil: contribuição e perspectivas para a biodiversidade, uso sustentável, conservação e serviços ambientais. EDUSP, São Paulo, pp. 285–300

OECD (1998a) Guidelines for the testing of chemicals. Number 213. Honeybees, acute oral toxicity test, in: OECD Environmental Health Safety Division (Ed.), Paris

OECD (1998b) Guidelines for the testing of chemicals, Number 214. Honeybees, acute contact toxicity test, in: OECD Environmental Health Safety Division (Ed.), Paris

Oliveira, E.E., Aguiar, R.W.S., Sarmento, R.A., Tuelher, E.S., Guedes, R.N.C. (2002) Seletividade de inseticidas a Theocolax elegans parasitóide de Sitophilus zeamais. Biosci. J. 18(2), 11–16

Ollerton, J., Winfree, R., Tarrant, S. (2011) How many flowering plants are pollinated by animals? Oikos 120(3), 321–326

Pinheiro, J.N., Freitas, B.M. (2010) Efeitos letais dos pesticidas agrícolas sobre polinizadores e perspectivas de manejo para os agroecossistemas brasileiros. Oecol. Australis 14(1), 266–281

Potts, S.G., Biesmeijer, J.C., Kremen, C., Neumann, P., Schweiger, O., Kunin, W.E. (2010) Global pollinator declines: trends, impacts and drivers. Trends Ecol. Evol. 25(6), 345–353

Ricketts, T.H., Regetz, J., Steffan-Dewenter, I., Cunningham, S.A, Kremen, C., et al. (2008) Landscape effects on crop pollination services: are there general patterns? Ecol. Lett. 11(5), 499–515

Ritz, C., Streibig, J.C. (2005) Bioassay Analysis using R. J. Statist. Software, 12(5), 1–22

Rocha, M.C.L.S.A. (2012) Efeitos dos agrotóxicos sobre as abelhas silvestres no Brasil: proposta metodológica de acompanhamento. Ibama, Brasília

Roubos, C.R., Rodriguez-Saona, C., Isaacs R. (2014) Mitigating the effects of insecticides on arthropod biological control at field and landscape scales. Biol. Control 75, 28–38

Sanchez-Bayo, F., Goka, K. (2014) Pesticide residues and bees – A risk assessment. PLoS ONE 9(4), e94482, DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0094482

Santos, C.F., Acosta, A.L., Dorneles, A.L., Santos, P.D.S., Blochtein, B. (2016). Queens become workers: pesticides alter caste differentiation in bees. Sci. Rep. 6, 31605

Silva, I.P., Oliveira, F.A.S., Pedroza, H.P., Gadelha, I.C.N., Melo, M.M., Soto-Blanco, B. (2015) Pesticide exposure of honeybees (Apis mellifera) pollinating melon crops. Apidologie 46(6), 703–715

Slaa, E.J., Chaves, L.A.S., Malagodi-Braga, K.S., Hofstede, F.E. (2006) Stingless bees in applied pollination: practice and perspectives. Apidologie 37(2), 293–315

Stevenson, J.H. (1978). The acute toxicity of unformolated pesticides to worker honey bees (Apis mellifera L.). Pl. Path. 27(1), 38–40

Stoner, K.A., Eitzer, B.D. (2013) Using a hazard quotient to evaluate pesticide residues detected in pollen trapped from honey bees (Apis mellifera) in Connecticut. PLoS ONE 11(7), e0159696, DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0077550

Suchail, S., Guez, D., Belzunces, L.P. (2000) Characteristics of imidacloprid toxicity in two Apis mellifera subspecies. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 19(7), 1901–1905

Sylvia, M. (2010) Pesticide Safety 2010- Insecticides update, bee toxicity and management decisions. http://scholarworks.umass.edu/cranberry_extension [Accessed 2 Oct 2013]

Tomé, H.V., Ramos, G.S., Araújo, M.F., Santana, W.C., Santos, G.R., et al. (2017). Agrochemical synergism imposes higher risk to Neotropical bees than to honeybees. R. Soc. Open Sci. 4(1), 160866

Venturieri, G. C., Alves, D.A, Villas-Bôas, J. K., Carvalho, C. A., Menezes, C. et al. (2011) Meliponicultura no Brasil: Situação atual e perspectivas futuras para o uso na polinização, in: Imperatriz-Fonseca, V.L., Canhos, D.A.L., Saraiva, A.M., Polinizadores no Brasil: contribuição e perspectivas para a biodiversidade, uso sustentável, conservação e serviços ambientais. EDUSP, São Paulo, pp. 227–255

Wiest, L., Buleté, A., Giroud, B., Fratta, C., Amic, S. Lambert, O., Pouliquen, H., Arnaudguilhem, C. (2011) Multi-residue analysis of 80 environmental contaminants in honeys, honeybees and pollens by one extraction procedure followed by liquid and gas chromatography coupled with mass spectrometric detection. J. Chromatogr. A 1218(34), 5743–5756

Xavier, V.M., Message, D., Picanço M.C., Bacci, L, Silva, G.A., Benevenute, J.S. (2010) Impact of Botanical Insecticides on Indigenous Stingless Bees (Hymenoptera: Apidae). Sociobiology 56(3), 713–725

Yu, S.J. (1987) Biochemical defense capacity in the spined soldier bug (Podisus maculiventris) and its lepidopterous prey. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 28(2), 216–233

Yu, S.J., Robinson, F.A., Nation, J.L. (1984) Detoxication capacity in the honey bee, Apis mellifera L. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 22(3), 360–368

Acknowledgements

We thank Dra. Guendalina Turcato Oliveira (PUCRS) for assistance in the preparation of the solutions used in the experiments, Dr. Alexandre Arenzon (UFRGS) for their support in statistical analysis and National Counsel of Technological and the Scientific Development (CNPq) for scholarship.

Contributions

A.L.D conceived this research and designed experiments, statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript. A.S.R. statistical analyses and wrote the manuscript. B.B. supervised the project.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Manuscript editor: Monique Gauthier

Toxicité des pesticides organaphosphorés vis-à-vis des abeilles sans aiguillon Scaptotrigona bipunctata et Tetragonisca fiebrigi

toxicité aigüe par voie orale / toxicité aigüe par contact / chlorpyrifos / phosmet / pollinisateurs

Toxizität von Organophosphat-Pestiziden für die stachellosen Bienen Scaptotrigona bipunctata und Tetragonisca fiebrigi

akute orale Toxizität / akute topikale Toxizität / Chlorpyriphos / Phosmet / Bestäuber

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dorneles, A.L., de Souza Rosa, A. & Blochtein, B. Toxicity of organophosphorus pesticides to the stingless bees Scaptotrigona bipunctata and Tetragonisca fiebrigi . Apidologie 48, 612–620 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-017-0502-x

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13592-017-0502-x