Abstract

There are few phrases in the Western world that evoke as much emotion or as powerful an image as the words “shark” and “attack.” However, not all “shark attacks” are created equal. Under current labels, listings of shark attack may even include instances where there is no physical contact between shark and human. The dominant perception of intent-laden shark “attacks” with fatal outcomes is outdated as a generic term and misleading to the public. We propose new descriptive labels based on the different outcomes associated with human–shark interactions, including sightings, encounters, bites, and the rare cases of fatal bites. We argue two central points: first, that a review of the scientific literature shows that humans are “not on the menu” as typical shark prey. Second, we argue that the adoption of a more prescriptive code of reporting by scientists, the media, and policy makers will serve the public interest by clarifying the true risk posed by sharks and informing better policy making. Finally, we apply these new categories to the 2009 New South Wales Shark Meshing Report in Australia and the history of shark incidents in Florida to illustrate how these changes in terminology can alter the narratives of human–shark interactions.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Science plays a powerful role in describing and labeling the natural world, providing social meaning for phenomena in nature. New scientific names and explanations shape our understanding as scientific discoveries replace old myths and mysteries. An example of this process is our evolving knowledge about sharks and shark bites on people. For centuries, the question “Why do sharks bite?” has implicitly also asked “What do shark bites mean?” The answers to these questions have implications for the way scientific discourse informs the public and policy makers. The subject of shark bites illustrates how vivid terms like “attack” are difficult to replace and how inflammatory rhetoric can elicit knee-jerk policy responses. The issue is not simply what to call human–shark interactions; it is about the enduring responsibility of science to advance its thinking without leaving the public behind.

Three labels stand out historically in the scientific as well as public treatment of shark bites on people. These are the concept of the “man-eater” shark, “rogue” shark, and the term “shark attack,” all of which originate from scientific studies. The lingering use of the phrase “shark attack” by media and government sources to report on human–shark interactions has led to a criminalization of shark bites. Indeed, the use of the “rogue” shark concepts and intent-laden words like “attack” can give sharks a perceived trait of malicious “agency” and support government overreactions to shark bites. In this paper, we show that an objective analysis concludes that shark bite discourse must be changed both scientifically and publicly, and we propose a different model for consideration. We suggest that shark “attack” terminology is outdated, and we offer new categories for scientists and the media to report more accurately on these events.

Construction of the man-eater label

The scientific system of species classification and description originated by Carl Linneaus (1758)—the same system that identifies humans as Homo sapiens—was the genesis for the label of “man-eater” for the white shark, Carcharodon carcharias. Linneaus’ description of this species included noting that “it strikes” (dorfo plano), has teeth of armor (dentibus ferrates), and was likely responsible for swallowing Jonah (Linneaus 1758, p. 235), whose story had been widely published in the 1679 Lectiones Morales in Prophetam Jonam by Angelo Paciuchelli and Charles de Marimont. Linnaeus’ historic volumes redefined the scientific and social world, and white sharks were singled out for their motivation as a man-eater.

From there, the story of the danger posed by sharks grew. In Thomas Pennant’s 1812 volume British Zoology, a stated characteristic of white sharks was their “greediness after human flesh” (p. 140). In 1845, Samuel Goodrich wrote that the shark is the “dread of mankind in the seas where it is found” (Goodrich 1845, p. 317). “Man-eater” came to virtually define white sharks (Jordan and Gilbert 1880), but the label also was used for other species in other areas. For example, in Hawai’i, the term niuhi meaning “man-eater” was used in native songs, most likely referring to the tiger shark (Titcomb and Pukui 1951, p. 4).

In Europe, colonial experiences shaped understandings of sharks. British big-game hunter Sir Samuel Baker’s expeditions in Asia and Africa led him to conclude that individual tigers, Panthera tigris, can become “man eaters” within a local area (Baker 1890; Blanford 1891). This concept of a predator that has acquired a “taste for human flesh” was projected onto sharks. In 1899, William Bryce wrote in the British Medical Journal about shark bites on three people on the same day in Port Said, Egypt. He noted that “many people have expressed the opinion that it must have been one shark which bit all three boys, and I think this very likely” (Bryce 1899, p. 1534).

Historical accounts at this time in the USA often differed, with scientists arguing that dangerous sharks could only be found in warmer southern waters. A report in the New York Times in 1865 recounted the story of Peter Johnson, a fisherman aboard a schooner in Lubec, Maine, who was bitten by a shark “that must have been of the species known as ‘man-eater’” (NY Times 1865). Yet the report notes that “man eaters” are “common in low latitudes” and “seldom, if ever attack mankind” (NY Times 1865). In 1916, interest in shark behavior rose dramatically following a cluster of fatal shark bites in New Jersey. Initially, Frederic Augustus Lucas of the American Museum of Natural History stated that it must not have been a shark because “sharks have no such powerful jaws” (Webster 1962, p. 87). He later concluded that he was wrong, and the shark in question must have been demented or “mad.”

In Australia, ocean swimming during the day was illegal from the late 1830s until 1902, due to concerns about propriety (Neff 2012), and the first reported shark bite was not documented until 1915, at an ocean beach in Sydney (Maxwell 1949). Fatal incidents followed at Sydney beaches, yet responses were limited. New South Wales Fisheries expert David Stead offered a statement on shark behavior in 1929, noting that “sharks do not patrol beaches on the off-chance of occasionally devouring human prey” (NSW 1929, p. 2). As a result, an Australian government report at the time referred to most cases of fatal shark bites as shark “accidents” (Neff 2012).

However, more shark bites ensued in Australia, and a 1933 study by Sydney surgeon Sir Victor Coppleson attempted to reconcile the competing international theories. Correspondence from the USA urged him to address this disagreement and to warn the public of possible “shark rabies” (Coppleson archives 1964). Coppleson concluded that the “evidence that sharks will attack man is complete” (Coppleson 1933, p. 466). Following publication of his article, the terminology in Australia changed to favor the more dominant shark “attack” language, which portrayed certain sharks as “man killers” (Coppleson 1933). Yet, the question of how to label different types of shark bites would persist, allowing the perception that all shark bites were of the “man-eating attack” variety.

In 1949, Australian author C. Bede Maxwell concluded that a “shark consciousness” was beginning to emerge, and she wrote that “‘accidents’ is the correct word to use in connexion [sic] with shark tragedies” (Maxwell 1949, p. 182). A global awareness of sharks was beginning to take shape with the deployment of hundreds of thousands of troops across the Pacific in World War II, bringing more sharks and people into contact than any previous time in human history. The US Navy produced a “Shark Sense” brochure to dissuade the concerns of pilots; however, the sinking of the U.S.S. Indianapolis in 1945, resulting in 60–80 fatalities by sharks (Sisneros and Nelson 2001), brought the subject of sharks and shark repellents to the forefront of government attention (Caldicott et al. 2001, p. 447).

Prior to the Indianapolis disaster, a chemical shark repellent called “Shark Chaser” had been developed and distributed to US military personnel at sea (Sisneros and Nelson 2001). The realization that this repellent was only partially effective led the Office of Naval Research (ONR) and other groups to focus further on the problem. Decades of ONR-sponsored research followed, resulting in great advances in our knowledge of shark physiology, behavior, and ecology (Gilbert 1963; Hodgson and Mathewson 1978). In 1958, a “Shark Research Panel” comprising Perry Gilbert, Sidney Galler, John Olive, Leonard Schultz, and Stewart Springer was established by the American Institute of Biological Sciences (AIBS), spurring a new discourse on categorizing human–shark encounters (Gilbert 1963; Caldicott et al. 2001).

That year, a meeting entitled “Conference on the Basic Research Approaches to the Development of Shark Repellents” was held in New Orleans, sponsored by AIBS, Tulane University, ONR, and the Navy Bureau of Aeronautics. The conference included 34 scientists from around the world. Shark “attack” classifications were suggested, with four categories outlined in a report by Leonard Schultz (Schultz 1963). These included: “unprovoked shark attacks,” in which sharks “make contact with the victim or gear;” “provoked shark attacks” that involve injuring, catching, or annoying sharks; “boat attacks” that involve contact with boating equipment; and “air and sea disasters” (Schultz 1963). To track trends in human–shark interactions around the world, the Shark Research Panel established the Shark Attack File, later known as the International Shark Attack File (ISAF), currently curated at the University of Florida.

The Schultz (1963) report advanced our thinking about shark attack in several ways. Bites or ramming on boats were separated out from bites on people, reducing the number of perceived “attacks” that occurred each year. The special cases of air and sea disasters were identified as unusual circumstances possibly evoking shark behavior not typical of that seen off ocean beaches. Most importantly, “provoked” responses by sharks that had been antagonized by swimmers, divers, or fishermen were separated from “unprovoked” attack behavior on what was perceived to be an innocent human victim. This provoked vs. unprovoked criterion is still used in today’s ISAF.

During the same post-WWII period, people began using ocean beaches for recreation at an increasing rate, as leisure time and personal and public transportation all rose after the mid-1940s. In the USA, “vacation travel boomed…and beaches on the East, West, and Gulf coasts were particularly popular destinations” (Harper 2007, p. 37). This expansion occurred in Australia and South Africa as well. Davies (1964, p. 141) stated that in South Africa, the “increased usage of the sea is related to such factors as increasing population, improved methods of transport, shorter working hours, and the increase of leisure time.” As a result, the growing popularity of ocean swimming, surfing, snorkeling, and scuba diving brought more people into potential contact with sharks every year.

The criminalization of shark attacks

The year 1950 saw the invention of both the bikini bathing suit and the “rogue shark” theory, the latter seeking to explain shark “attacks” and guide government responses. Coppleson presented the theory following up on his research in Australia to explore the motivations behind shark bites. He argued that the only sharks that bit humans were “rogue” sharks that have developed a taste for human flesh (Coppleson 1950; Coppleson 1959). This narrative built on the lone, man-eating predator concept from the late nineteenth century. Coppleson suggested that other sharks behave “normally” and are not likely to bite, and so he reclassified all shark “attacks” as those perpetrated by “rogue” sharks. In the 1950 Australian Medical Journal, he wrote:

The continued presence of man-eating sharks, the attacks in sequence and cessation of attacks once a particular shark is caught, suggests the guilt, not of many sharks, but of one shark. It suggests the presence of a vicious shark which patrols a certain area of the coast, of a river or of a harbor, for long periods.

This analysis gave sharks human agency and moved them from unseen “monsters of the deep” to a potentially more terrifying image as resident serial killers lurking in wait for human prey. Coppleson thus concluded that “such a shark must be hunted until it is destroyed” (Coppleson 1950, p. 8). It is this perceptual change in the treatment of shark behavior that constitutes the criminalization of this human–animal interaction (Michalowski 1985).

While sharks are not traditional criminals and shark bites are unconventional crimes, this characterization is consistent with the way actions and groups receive benefits or burdens. Jenness (2004, p. 150) notes that criminalization “targets a set of activities perceived to be attached to a social group deemed ‘in need of control’ by those in a position to stimulate, define and institutionalize criminal law.” In this case, sharks’ swimming is no longer considered innocent behavior; instead, this patrolling or cruising constitutes a threat. In David Webster’s book Myth and Maneater (1962, pp. 50, 67), this change can be seen as shark bites on people are labeled as a “molestation” and “assaults.” In response to these concepts of shark behavior, “shark control” programs are enacted by nations around the world. Shark bites have been treated as if they were crimes in the USA, South Africa, Australia, and elsewhere. During the spate of incidents in New Jersey in 1916, a request for action was discussed during a War Cabinet meeting (Webster 1962). Following a series of four fatal shark bites in 13 days in 1957 along the Natal South Coast of South Africa, rogue sharks were identified as the culprits (Davies 1964, p. 71). In response, the South African Navy was enlisted, and a frigate, the S.A.S. Vrystaat, was sent from Cape Town to drop more than sixty 100-lb depth charges near the shoreline off the South Coast (Davies 1964). In the USA in 1961, fear of shark attacks led to directed longline fishing for sharks off the coast of New Jersey (Carlson et al. 2008). In Australia, culling nets were added to Queensland beaches in 1962 (Gribble et al. 1998). These measures were consistent with current scientific understanding of sharks. Indeed, Davies (1964, p. 65) wrote that the “Blue Pointer [a previous name for white sharks] is a voracious and aggressive species which attacks humans and even small boats with little hesitation.” The prevailing attitude at the time had become “the only good shark is a dead shark” (Gruber and Manire 1991).

By the time the best-selling novel Jaws and the subsequent blockbuster movie appeared in 1974 and 1975, respectively, the criminalization of shark bites was nearly complete: the “man-eater” label implied an intent-driven monster that was seeking human prey. The rare discoveries of human remains inside sharks reinforced this image and validated scientists’ worst fears (Maxwell 1949). The rogue shark theory appeared to provide a scientific basis for malicious shark behavior, from which there could be only one outcome in human–shark interactions: the fatal outcome resulting from being hunted, killed, and eaten alive by a shark. When Peter Benchley’s book appeared, the story of a rogue shark terrorizing a seaside town brought the graphic fear of criminal sharks home to millions. The enactment of anti-shark policies including shark hunts, shark derbies, and beach nets became punitive measures for the perceived public good. Recreational “monster fishing” for sharks skyrocketed after 1975, and shark “kill” tournaments in the USA became more popular than ever before (Hueter 1991). More recently, real shark hunts mirroring the fictional response in Jaws have been used following clusters of shark bite incidents in Egypt, Russia, the Seychelles, Mexico, Réunion Island, and Western Australia (Neff and Yang 2012).

Jaws was a worldwide phenomenon and framed a clear story: humans were on the shark’s menu. Risk theorist Paul Slovic (2004) noted that for hazards like shark bites, images, words, and symbols can be triggers to paint a picture of scary outcomes. He further stated that “[w]e have found that every hazard has a unique profile of qualities (much like a personality profile) that influences perception and acceptance of its risk” (Slovic 2004, p. 985). After Jaws, the shark “attack” profile was linked to the unforgettable images of the film and reinforced one, and only one, vivid and dreaded outcome. All shark “attacks” were perceived as equal, and wherever sharks roamed—which is off most swimming beaches of the world—going into the ocean meant you were risking your life to the bloodthirsty jaws of a shark.

Why “shark attack” is the wrong nomenclature

As a label for a broad array of human–shark interactions, “shark attack” is an erroneous characterization for a number of reasons. Shark “attack” language unreasonably amplifies social perceptions of risk. It provides a heuristic model that facilitates mental shortcuts to connect words with images and feelings (Slovic 2004). A loaded phrase such as “shark attack” compounds the perceptions of other crimes and outcomes, similarly to the term “home invasion.” Such “perceptually contemporaneous (PC) offenses” can cause potential victims’ images to cascade into perceptions about other events (Warr 1984, 1987). For example, the fear of a robbery is amplified by the perceived connection it has with being assaulted, raped, or murdered. Likewise, the term “shark attack” does not elicit thoughts of minor scrapes or bites; instead, it conjures horrific, bloody scenes of being consumed alive by an evil predator.

As a result, the generic term “shark attack,” which is used to label a multiplicity of human–shark interactions, is misleading to the public. Reports of shark “attack” make little distinction between minor events and fatal incidents. Bites from non-threatening sharks like the wobbegong, which account for 5.5 % of all shark “attacks” in Australia since 1900 (NSW 2009), are not distinguished from more serious bites by other species of sharks when all events are labeled shark “attacks.” The term “shark attack” can even include events where there is no physical contact with a person. For example, sharks simply making contact with kayaks may be counted and reported as “attacks” (NSW 2009). Clearly, when the phrase “shark attack” is used, the public is led to conclude that this must involve direct contact resulting in major injuries to the “victim.”

In addition, shark attack language has been politicized, and the shark “attack” label is sometimes used for political purposes when shark bites occur. The words “shark attack” can create a perception of a premeditated crime, lowering the public’s threshold for accepting shark bite incidents as random acts of nature. The narrative establishes villains and victims, cause and effect, perceptions of public risk, and a problem to be solved. A shark fatality in Western Australia in 2011 led the local shire president to state that “[a] lot of people say the water is the shark’s territory, but I think if they can find the shark (responsible) they should get rid of it.” And he added, “[i]f they have attacked [our italics] a human in one of those areas they may want to do it again” (Hickey 2011). Policies that respond to shark “attacks,” therefore, may be more understandable and acceptable to the public when they rely on familiar stereotypes, even if they have no relationship to what actually takes place. In short, a pattern exists in which the designation of a shark “attack” raises media attention that provokes a government response, even when the event may not be serious or governable (Neff and Yang 2012).

It is not surprising, therefore, that the selection of policy responses can include “hunting the shark down,” drawing from the movie legend. This reaction raises an important final point, that the “rogue” shark theory is unsupported by scientific data. Although sharks may have ample opportunity to feed on humans, the incredible rarity of incidents suggests that shark bites in most cases represent what amounts to a tactical and biological dead end for the sharks. Raising public awareness of this involves conceptualizing the scientific data in a way that makes this clear, even as dramatic and sometimes fatal incidents occur and are publicized. Fatal shark bites in 2010–2012, in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt, the Seychelle Islands, Réunion Island, and off Western Australia, brought back stories of “rogue” sharks, yet the post-Jaws era science stands firm on this issue: sharks have not put humans on their menu.

Moving away from shark “attack” language

In 1974, David Baldridge’s groundbreaking analysis of shark bite data, conducted at Mote Marine Laboratory in Florida, introduced the first outcome-based approach to categorize human–shark interactions. A number of Baldridge’s conclusions ran counter to Coppleson’s. For example, Baldridge did not support Coppleson’s argument that water temperature was the primary dependent variable linking shark feeding behavior with shark attack predictability. Baldridge (1974) stated that “the correlation between warm water and shark bites is a reflection of when people are more likely to go into the water, not when sharks are excited to feed” (p. 17). In addition, Baldridge confirmed Springer’s (1963) hypothesis that, beyond a certain water temperature, sharks show an inverse relationship between feeding and temperature. Baldridge (1974) stated that “the real shark attack season” would be that time when local waters are warm enough for human swimmers (above 70 °F) and not too hot for sharks (less than 85 °F) (Baldridge 1974, p. 18).

Over the past 30 years, many shark biologists have dedicated themselves to understanding shark behavior, including biting and feeding patterns. In 1984, Timothy Tricas and John McCosker suggested that white sharks might mistake humans for seals in certain circumstances, resulting in a “bite and spit” behavior that could explain why human fatalities do not always occur in white shark attacks (Tricas and McCosker 1984). Samuel Gruber reviewed the analyses by Baldridge (1974) and Nelson et al. (1986) and decided it is unreasonable to draw conclusions about why sharks bite without looking at the totality of shark motivation and behavior and ecosystem conditions (Gruber 1988, p. 10). He stated that the contributing factors for shark bites include random “opportunity,” “interference” with reproductive activity, defensiveness against a threat or competition, and trespassing into a shark’s space. Gruber concluded “the majority of cases where sharks act aggressively against humans are probably motivated by social factors such as fear, aggression or sex and are entirely unrelated to feeding” (Gruber 1988, p. 12).

This discussion reveals a primary shortcoming of the Schultz (1963) categorization of “provoked” vs. “unprovoked” shark attacks. It is easy to classify cases of divers spearing sharks, grabbing their tails, or attempting to ride them, or fishermen hooking sharks and pulling them into their boats, as “provoked” incidents. What is not so easy to judge is if a swimmer who passes very close to a shark “minding its own business” is, or is not, provoking that shark to respond to a violation of its personal space by biting the intruder. This and other examples underscore the failings of motivation/intent-laden categories of human–shark interactions, such as the Schultz (1963) provoked/unprovoked distinction, rather than an outcome-based system. We simply do not, and probably cannot, understand enough about the specifics of shark behavior in all cases to classify the motives and intentions of every biting shark in a clear, objective way.

More recently, several factors have driven an alternative narrative to the human–shark interaction story. These include: (a) the emergence of shark conservation biology demonstrating the worldwide vulnerability of sharks, including white sharks; (b) a decline in shark bite fatality rates due to better first responder medical care; and (c) an increased awareness of the diversity of human–shark outcomes, even when shark bites occur. Heneman and Glazer’s (1996) article documenting new legal protection for white sharks, successfully implemented in California in 1994, was entitled “More rare than dangerous” and noted that a shark bite victim wrote in favor of protection despite having been “mauled” by a white shark (p. 485). Analysis by Caldicott et al. (2001) highlighted the increasing survival rates from shark bites, up to 87 % (p. 449). The authors of that study identified a number of shark bite situations including “hit and run,” “sneak attack,” and “bump and bite” (Caldicott et al. 2001, p. 449).

Efforts to focus on the diversity of outcomes from human–shark interactions, even when shark bites occur, have increased over time. Immediately following the US east coast’s so-called “Summer of the Shark” in 2001, one of the authors (RH) recommended that most “shark attacks” should more correctly be referred to as “shark bites,” in the same way that we distinguish an aggressive but nonfatal “dog bite” from a serious, sometimes fatal “dog attack.” This author particularly focused this message on the news media and its overuse of the term “shark attack” that resulted in a misled and sometimes panic-stricken public. Other scientists also have begun to advocate for a change in “shark attack” language. Cliff (1991) used a modified definition to calculate shark bites in South Africa. Recent research by Lentz et al. (2010), using data from the ISAF, led to the development of a “shark bite severity scoring system” that identifies five levels of shark bite injuries, from minor to fatal wounds, providing a leap forward in clinical assessments of shark injuries. Extending into the popular culture, in her 2011 book Demon Fish, journalist Juliet Eilperin sought to find a middle ground by referring to shark bites as “strikes” (Eilperin 2011).

Observations of sharks in proximity to human swimmers in the ocean demonstrate that the animals do not usually take an interest in people. Sightings by New South Wales Fisheries staff, including Vic Peddemors and Amy Smoothey, have revealed that bull sharks regularly swim close to hundreds of human swimmers in Sydney Harbour and ignore them all (ABC 2011). In Cape Town, South Africa, the Shark Spotters program has reviewed more than 1,100 sightings of white sharks swimming around surfers and near bathers. Bathers were alerted and got out of the water, and the visiting sharks swam away (Shark Spotters 2012). This story repeats itself in Port Stephens, Australia, where shark biologist Barry Bruce has studied juvenile white sharks that consistently ignore people in the nearby surf (Gilligan 2012). These observations point to the need for a more sophisticated public education effort on the subject of shark aggression (and nonaggression) towards humans. One example of such an effort can be seen in beach signage used by the city of Port Lincoln in South Australia. The signs identify varying levels of concern when white sharks are in local waters, using sighting categories of: (a) sharks away from shore, (b) sharks inshore, and (c) emergency situations where humans and sharks are very close together.

Clearly, classifying virtually all contact between sharks and humans as some form of shark “attack” misrepresents the facts and misinforms the public. It is invalid on both scientific and public policy grounds. Different language and categories of human–shark interactions are needed.

Categorizing human–shark interactions

To address this problem, we propose a new system of four categories for scientists, the media, policy makers, and the public to use in classifying human–shark incidents. We base this categorization on outcomes rather than motivations or intent. The removal of implied intent from shark “attack” discourse attempts to provide a unified model for reporting interactions, illustrate the diversity of outcomes, decriminalize sharks in the mind of the public, and create a more objective understanding of the relationship between humans and sharks in shared ocean spaces. These categories are:

-

1.

Shark sightings: Sightings of sharks in the water in proximity to people. No physical human–shark contact takes place.

-

2.

Shark encounters: Human-shark interactions in which physical contact occurs between a shark and a person, or an inanimate object holding that person, and no injury takes place. For example, shark bites on surfboards, kayaks, and boats would be classified under this label. In some cases, this might include close calls; a shark physically “bumping” a swimmer without biting would be labeled a shark encounter, not a shark attack. A minor abrasion on the person’s skin might occur as a result of contact with the rough skin of the shark.

-

3.

Shark bites: Incidents where sharks bite people resulting in minor to moderate injuries. Small or large sharks might be involved, but typically, a single, nonfatal bite occurs. If more than one bite occurs, injuries might be serious. Under this category, the term “shark attack” should never be used unless the motivation and intent of the animal—such as predation or defense—are clearly established by qualified experts. Since that is rarely the case, these incidents should be treated as cases of shark “bites” rather than shark “attacks.”

-

4.

Fatal shark bites: Human–shark conflicts in which serious injuries take place as a result of one or more bites on a person, causing a significant loss of blood and/or body tissue and a fatal outcome. Again, we strongly caution against using the term “shark attack” unless the motivation and intent of the shark are clearly established by experts, which is rarely the case. Until new scientific information appears that better explains the physical, chemical, and biological triggers leading sharks to bite humans, we recommend that the term “shark attack” be avoided by scientists, government officials, the media, and the public in almost all incidences of human–shark interaction.

Applying these categories to existing data

Australia and the USA provide valuable case studies for this analysis of shark attack terminology, as these nations lead the world in the number of reported shark “attacks” (ISAF 2012a). The US state of Florida was ground zero for the “Summer of the Shark” in 2001, while the Australian state of New South Wales (NSW) and its capital Sydney saw its own “Summer of the Shark” in 2009. The case studies below examine legacies from these episodes. In NSW, the government’s 2009 report on shark “attacks” is evaluated using our new categories; in Florida, the state’s global reputation as a hot spot for shark “attacks” is reconsidered.

Case study 1: New South Wales

In Australia, NSW has the longest contemporary history in responding to human–shark interactions and is second in reported shark “attacks,” with 237 as compared with Queensland’s 245 (ASAF 2012). Following a series of incidents in 2009, the state government released the 2009 New South Wales Shark Meshing Program (SMP) Report. A quantitative and qualitative analysis is reviewed in the report’s Table 7, entitled “Details of unprovoked shark attacks by region in NSW, 1791 to March 2009” (NSW 2009, pp. 28–33). We used this table, which classifies 200 shark attacks in the state between 1900 and 2009 (NSW 2009, p. 33), to test our proposed model.

We reclassified the government report characterizations of shark “attacks” under our “sightings, encounters, bites, and fatal bites” categories based on details provided in the report. These details included notations regarding: (a) “outcome,” (b) “activity,” (c) “suspected species,” and (d) whether the beach was part of the shark net program “at the time” of the incident (NSW 2009, pp. 28–33). In cases where the details appear limited, the most conservative label was used.

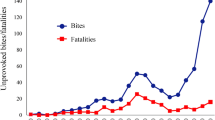

Of the 200 identified shark “attacks,” 38 resulted in no injury. Reclassifying these incidents as one shark sighting and 37 shark encounters reduces the number of reported shark “attacks” in New South Wales by 18.5 % (Table 1). In addition to reconsidering noninjury incidents, we can also reclassify nonfatal injuries from relatively benign species, namely the wobbegong shark (Orectolobus spp.), as shark “bites.” This reduces shark “attack” numbers by a further 5.5 % (or 11 bites) between 1900 and 2009.

A full application of the proposed classifications offers a new narrative to scientists, policy makers, and the media. First, the total number of potential shark “attacks” recorded in New South Wales waters is reduced by 72 % between 1900 and 2009, by 94 % between 1959 and 2009, and by 96 % between 1979 and 2009 (Table 1). The number of fatal shark bites declined significantly between the first 59 years of the study (47 fatalities) and the last 50 years of the study (9), perhaps due to improvements in emergency medical care or better swimmer education. Next, 19 % of the so-called “attacks” between 1900 and 2009 are better classified as “encounters,” which appears to reflect increases in the number of recreational water users choosing to surf, kayak, body board, and paddle board. Lastly, the relatively similar numbers of shark bites over time—38 from 1900 to 1959 (0.6 bite/year), 24 from 1959 to 1979 (1.2 bites/year), and 44 from 1979 to 2009 (1.5 bites/year)—reinforces a fundamental risk dynamic that is present when entering the water. Thus, viewing the data in these categories provides an instructive picture for beach safety educators and suggests emerging trends that may provide valuable information to user groups. We argue that considering future reporting of shark “attack” data in this manner provides a more informative and helpful story to the public and places the demand for policy responses in proper context.

Case study 2: Florida

Florida is often labeled the “Shark Attack Capital of the World” for the number of incidents with sharks that occur off Florida beaches. The ISAF lists 637 confirmed cases of unprovoked shark “attacks” in Florida waters between 1882 and 2012 (ISAF 2012b). Of these, 11 (<2 %) resulted in fatalities. In cases where the type of shark could be identified, about half involved species not associated with fatal attacks (blacktip shark, Carcharhinus limbatus, 20 %; spinner shark, Carcharhinus brevipinna, 16 %; nurse shark, Ginglymostoma cirratum, 7 %; sand tiger, Carcharias taurus, 6 %). These species tend to inflict small bites or scrapes on a hand, foot, arm, or leg that do not result in life-threatening wounds. About one quarter of Florida incidents involved species more associated with fatal “attacks” (bull shark, Carcharhinus leucas, 20%; tiger shark, Galeocerdo cuvier, 5%; mako, Isurus spp., 1%) (ISAF 2012c).

Applying our approach to the classification of shark incidents in Florida, therefore, only 11 would be labeled as “fatal shark bites” over a span of 129 years; the other 626 would be reclassified as either “shark encounters” or “shark bites” with perhaps a small fraction qualifying as “shark sightings.” In this way, the number of recorded shark “attacks” in Florida would be reduced by 98 %. This approach would facilitate a major shift in media reporting based on outcomes, including minor injuries and bites from non-threatening species. Florida could no longer be labeled as the world’s shark attack capital compared to other areas with greater numbers of fatalities, including parts of Australia, South Africa, Réunion, and Brazil (ISAF 2012a).

In contrast, the shark “attack” label has been widely adopted in media reporting on Florida incidents. During the summer of 2001, Florida’s seasonal pattern of shark–human interactions included a clustering of relatively minor shark “bites” by mostly small- or medium-sized sharks on surfers and swimmers off the Florida east coast. Prior to these occurrences, a media storm erupted around one very serious shark bite, by a more dangerous bull shark, on an 8-year-old boy in the Florida panhandle region. The boy’s arm was removed and he suffered debilitating injuries due to blood loss, but he did not die from the incident. Prolonged attention to the boy’s story, combined with reporting of the less serious bites in Florida and some unusual fatalities elsewhere on the US east coast, resulted in headlines in newspapers and magazines reinforcing the label of Florida as a global shark “attack” hot spot. In the end, the number of incidents in Florida in 2001 was about the same as in 2000 and 2002—34 as compared with 37 and 29, respectively—with only a single fatality recorded in Florida in 2001 (ISAF 2012a).

A content analysis of newspaper reporting was also conducted by downloading Associated Press (AP) articles from Factiva, an online news service database and research tool. A key-word search for “shark attack” showed 48 articles appeared during this Florida episode, between July 8, 2001 and August 25, 2001. Articles were coded manually and restricted to those AP stories appearing in Florida newspapers during this period, which included one incident involving an American in the Bahamas. None of the shark bites reported during this interval were fatal. Results show the word “attack” was used in the headlines of articles 79 % of the time (38 of 48) and was used a total of 201 times in the text of the 48 articles, or once every 159 words, with an average story length of 498 words. Given the disconnect between reported “attacks” and actual fatal outcomes, new labels should be adopted by media outlets to properly inform the public of the overwhelming number of human–shark interactions that are not life threatening.

In all, our new categories move the dialog forward in a number of important ways. These classifications are more scientifically accurate because they focus on analyzing outcomes rather than intent, which rarely can be known. The variations in outcomes from shark bites signal a more complex relationship than simply “shark attacks swimmer,” a complexity that should be identified for the public. Our categorization accomplishes this and also provides a uniform method for informing the public. It eliminates variations in reporting based on limited understanding and outdated terminology. Our categories also provide data that can be used by policy makers to improve beach safety programs and respond to the increased use of personal watercraft (e.g., increases in kayak use resulting in more shark encounters). Most importantly, our proposed change in shark “attack” reporting alters the representation of all shark bites as the same. It challenges the powerful stereotypes that conjure vivid images and reactions regardless of the reality. As a result, this creates space for new considerations of ocean safety and responses to shark bite prevention based on a more accurate perception of real-world events.

Conclusions

We suggest that our proposed terminology paints a more accurate and less inflammatory picture of the shark risk for New South Wales and Florida beachgoers. The same principle will no doubt apply to many other areas around the world. The inclusion of sightings and encounters in particular allows for the consideration of interactions with sharks that do not result in injury. If the only measures available for humans and sharks are records of tragic circumstances, then a decidedly one-sided narrative will result.

This paper has offered a review of the scientific and social constructions of sharks as “man-eaters” or “rogue” animals and of “attack” categorizations. We argue that the phrase “shark attack” is misplaced scientifically and misleading to the public. In addition, we propose categories that offer a more balanced approach to help eliminate biases in public understanding and policy overreactions. In short, this is a call to scientists, public officials, and the media to reconsider their discourse on the subject of sharks and to improve the accuracy of information provided to the public. The selection of language regarding human–shark interactions is not an issue of semantics or simply playing with words. The time has come to codify our contemporary understanding of human–shark interactions into new categories that move beyond the “Jaws effect” and acknowledge the public value of a balanced, outcome-based approach.

References

ABC (2011) Sharks tracked as they cruise swimming spots. ABC PM. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. August 25, 2011. http://www.abc.net.au/pm/content/2011/s3302316.htm. Accessed 25 Aug 2011

ASAF (2012) Latest figures. Australian shark attack file, Taronga Zoo. http://www.taronga.org.au/animals-conservation/conservation-science/australian-shark-attack-file/latest-figures. Accessed 14 Nov 2012

Baker S (1890) Wild beasts and their ways: reminiscences of Europe, Asia, Africa and America. Macmillan and Co., London

Baldridge HD (1974) Contributions from the Mote Marine Laboratory. Shark attack: a program of data reduction and analysis. 1 (2): Allen Press, Lawrence, KS. pp 1–98, https://dspace.mote.org/dspace/bitstream/2075/679/1/MTR%20A-1974.pdf. Accessed 20 June 2012

Blanford WT (1891) Fauna of British India: mammals. Taylor and Francis, London

Bryce W (1899) Three cases of shark bite. Br Med J 2:1534, Dec. 2, 1899

Caldicott D, Mahajani R, Kuhn M (2001) The anatomy of a shark attack: a case report and review of the literature. Inj Int J Care Injured 32:445–453

Carlson J, Cortes E, Neer J, McCandless C, Beerkircher L (2008) The status of the United States population of night shark, Carcharhinus signatus. Mar Fish Rev 70(1):1–13

Cliff G (1991) Shark attacks on the South African coast between 1960 and 1990. South Afr J Sci 87(10):513–518

Coppleson V (1933) Shark attacks in Australian waters. Med J Aust 1(15):449–466

Coppleson V (1950) A review of shark attacks in Australian waters since 1919. Med J Aust 2(19):680–687

Coppleson V (1959) Shark attack. Angus and Robertson, Sydney

Coppleson Archives (1964) Coppleson letters. New South Wales State Library

Davies DH (1964) About sharks and shark attack. Shuter and Shooter, Pietermaritzburg

Eilperin J (2011) Demon fish: travels through the hidden world of sharks. Knopf Doubleday, New York

Gilbert P (ed) (1963) Sharks and survival. D.C. Heath and Company, Boston

Gilligan J (2012) Great white shark nursery. Australian Geographic. January 25, 2012. http://www.australiangeographic.com.au/journal/great-white-shark-nursery.htm. Accessed 30 Oct 2012

Goodrich SG (1845) Illustrative anecdotes of the animal kingdom. Bradbury, Soden, and Co., Boston

Gribble N, McPherson G, Lane B (1998) Effect of the Queensland Shark Control Program on non-target species: whale, dugong and dolphin: a review. Mar Freshw Res 49(7):645–651

Gruber S (1988) Why do sharks attack people? Naval Res Rev 40(1):2–19

Gruber S, Manire C (1991) The only good shark is a dead shark? In: Gruber S (ed) Discovering sharks. A volume honoring the work Stewart Springer. American Littoral Society, 14th edn. Special Publication, Highlands, pp 115–121

Harper MM (2007) The American home front: a national historic landmark theme study. U.S. National Parks Service 1–193. http://www.nps.gov/nhl/themes/homefrontstudy.pdf. Accessed 14 Nov 2012

Heneman B, Glazer M (1996) More rare than dangerous: a case study of white shark conservation in California. In: Klimley AP, Ainley DG (eds) Great white sharks: the biology of Carcharodon carcharias. Academic, San Diego, pp 481–491

Hickey P (2011) Mayor calls for killer shark to be culled. Perth Now. October 11, 2011

Hodgson E, Mathewson R (eds) (1978) Sensory biology of sharks, skates, and rays. Office of Naval Research, Arlington

Hueter RE (1991) Survey of the Florida recreational shark fishery utilizing shark tournament and selected longline data. Mote Marine Laboratory Technical Report 232A, Sarasota, FL

ISAF (2012a) ISAF statistics for the world locations with the highest shark attack activity (2000–2011) International Shark Attack File. http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/fish/sharks/statistics/statsw.htm. (updated January 30, 2012). Accessed 2 Sept 2012

ISAF (2012b) 1882–2011 map of Florida's confirmed unprovoked shark attacks (N = 637) International shark attack file. http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/fish/sharks/statistics/GAttack/mapFL.htm (updated January 30, 2012). Accessed 2 Sept 2012

ISAF (2012c) Species involved with unprovoked shark attacks in Florida 1920–2011 (N = 97) International shark attack file. http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/fish/sharks/statistics/FLspeciesattacks.htm (updated February 10, 2012). Accessed 2 Sept 2012

Jenness V (2004) Explaining Criminalization: From Demography and Status Politics to Globalization and Modernization. Annu Rev Sociol 30:141–171

Jordan DS, Gilbert CH (1880) Notes on sharks from the coast of California. Proceedings of the United States National Museum, 51–52

Lentz AK, Burgess GH, Perrin K, Brown JA, Mozingo DW, Lottenberg L (2010) Mortality and management of 96 shark attacks and development of a shark bite severity scoring system. Am Surg 76:101–106

Linnaeus C (1758) Systema Naturae. Edition Systema naturae per Regna tria naturae, secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. 10th Edition 1: 1–824

Maxwell CB (1949) Surf: Australians against the sea. Angus and Robertson, Sydney

Michalowski R (1985) Order, Law and Crime: An Introduction to Criminology. Random House, New York

Nelson D, Johnson R, McKibben J, Pittenger GC (1986) Agonistic attack on divers and submersibles by grey reef sharks Carcharhinus amblyrhynchos: anti-predatory or competitive. Bulletin of Marine Science 38(1):68–88

Neff C (2012) Australian beach safety and the politics of shark attacks. Coast Manag 40:88–106

Neff C, Yang J (2012) Shark bites and public attitudes: policy implications from the first before and after shark bite survey. Mar Policy 38:545–547

New York Times (1865) Fight with a shark. New York Times Sunday, September 17, 1865

NSW (1929) Summary of New South Wales Shark Menace Committee’s report. Report 86206-a. New South Wales, Australia

NSW (2009) Report into the NSW shark meshing (bather protection) program [public consultation document]. New South Wales Department of Primary Industries website, http://www.dpi.nsw.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/276029/Report-into-the-NSW-Shark-Meshing-Program.pdf. Accessed on 10 March 2012

Paciuchelli A, C De Marimont (1679) Lectiones morales in Prophetam Jonam

Pennant T (1812) British zoology, volume 3. 1812. William Eyres, for Benjamin White, London

Schultz L (1963) Attacks by sharks as related to the activities of man. In: Gilbert P (ed) Sharks and survival. D.C. Heath & Co, Boston

Shark Spotters (2012) Recent sightings. 2012. http://sharkspotters.org.za/recent-sightings. Accessed 20 June 2012

Sisneros J, Nelson D (2001) Surfactants as chemical shark repellents: past, present, and future. Environ Biol Fish 60:117–129

Slovic P (2004) What's fear got to do with it? It's affect we need to worry about. Missouri Law Rev 69:971–990

Titcomb M, Pukui M (1951) Native use of fish in Hawaii. Memoir no. 29. Suppl J Polyn Soc 60:1–146

Tricas T, McCosker J (1984) Predatory behavior of the white shark, Carcharodon carcharias, and notes on its biology. Proc Calif Acad Sci 43(14):221–238

Warr M (1984) Fear of victimization: Why are women and the elderly more afraid. Soc Sci Q 65(3): 681–702

Warr M (1987) Fear of victimization and sensitivity to risk. J Quant Criminol 3(1):29–46

Webster D (1962) Myth and the man-eater: the story of the shark. Angus and Robertson, Sydney

Acknowledgments

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2012 Australian Political Science Association Conference. We wish to thank Christine Ward-Paige for her insights on these topics and Associate Professor Rodney Smith and for his comments on earlier drafts. Funding to support this research comes from the Sydney Aquarium Conservation Fund, the University of Sydney Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, the Perry W. Gilbert Chair in Shark Research at Mote Marine Laboratory, and the Save Our Seas Foundation.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Neff, C., Hueter, R. Science, policy, and the public discourse of shark “attack”: a proposal for reclassifying human–shark interactions. J Environ Stud Sci 3, 65–73 (2013). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-013-0107-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13412-013-0107-2