Abstract

Introduction

Intensive insulin treatment for type 1 diabetes is associated with high risk of mild hypoglycemia. Mild hypoglycemia is usually treated orally with glucose, which may contribute to weight gain. Subcutaneous injection of low-dose glucagon may be a new treatment option for some occasions of mild hypoglycemia in individuals aiming for optimal glycemic control without gaining weight. We investigated under which occasions patients were interested to use low-dose glucagon.

Methods

In a prospective 2-week event-driven survey, participants registered every event of mild hypoglycemia (sensor or blood glucose ≤ 3.9 mmol/l and/or hypoglycemia symptoms). For each hypoglycemia event, participants registered whether they would have preferred to use low-dose glucagon if the treatment had been available.

Results

A total of 51 participants (13 men, mean ± SD age 43.6 ± 12.5 years, HbA1c 7.3 ± 0.7% (57 ± 8 mmol/mol), BMI 24.9 ± 3 kg/m2) were included. Each participant had on average 10 (range 3–23) mild hypoglycemia events during the 2-week survey period. Glucagon was preferred in 58% of the 514 mild hypoglycemia events (p > 0.05). Twelve percent of the participants had no desire to use glucagon for any hypoglycemia event. The preference pattern did not differ between sex, patient treatment modalities, and possible causes for hypoglycemia (all p > 0.05).

Conclusion

This study showed that a majority of our participants with type 1 diabetes were interested in using low-dose glucagon for the treatment of mild hypoglycemia.

Funding

This work was funded by a research grant from the Copenhagen University Hospital Hvidovre and by the Danish Diabetes Academy supported by the Novo Nordisk Foundation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Individuals with type 1 diabetes are recommended intensive insulin therapy to keep near-normal blood glucose levels to prevent late-diabetes complications [1]. Unfortunately, the intensive therapy often leads to events of hypoglycemia because of relative insulin overdosing [2, 3]. During a mild hypoglycemia event, individuals can restore normal blood glucose levels by oral intake of glucose (e.g., glucose tabs, food, snacks, and juice) [4, 5]. However, the glucose along with other macronutrients consumed to restore normoglycemia may add to the overall daily calorie intake and cause weight gain [6, 7]. The consumed glucose often exceeds the amount necessary for recovery, resulting in post-rescue hyperglycemia [8]. Furthermore, patient do not necessarily take correction insulin dose to cover for the excess glucose. Recent reports show that half of the total type 1 diabetes population are overweight and obese with the highest prevalence of 67–69% in the age group above 26 years [9,10,11]. Therefore, a treatment approach for mild hypoglycemia which does not induce weight gain or post-rescue hyperglycemia is attractive for individuals with type 1 diabetes.

One alternative is subcutaneous injection of low-dose glucagon that can increase plasma glucose in a dose-dependent manner without adding extra calories to the individuals. Until recently, glucagon was only available in a powder form and needed to be dissolved before use to treat a severe hypoglycemia—a hypoglycemia state when patients are unable to consume glucose orally. Now, there are alternative glucagon products available (e.g., GVOKE® Xeris; Baqsimi®, Eli Lilly; and BioChaperone® glucagon, Adocia) for the treatment of severe hypoglycemia. However, glucagon is not approved for non-severe hypoglycemia. Recent studies have shown that 0.1 mg glucagon administered subcutaneously is able to raise blood glucose by 2.3 mmol/l and sustain this level for 1–2 h in clinical settings [12]. However, it is uncertain whether individuals with type 1 diabetes would prefer to use low-dose glucagon injections rather than orally administered glucose to treat and prevent mild hypoglycemia.

In this study, we investigated in a hypothetical setting whether individuals with type 1 diabetes would prefer managing mild hypoglycemia with orally administered glucose or with a subcutaneous injection of low-dose glucagon (if it had been available). Further, we examined under which occasions glucagon or glucose were preferred.

Methods

Study Design

An event-driven survey for registration of every mild hypoglycemia event for 2 weeks.

Study Participants

Participants were included if they were at least 18 years old, diagnosed with diabetes for at least 2 years, had an HbA1c ≤ 8.0% (64 mmol/mol), able to count carbohydrates, and had at least one event of mild hypoglycemia per day prior to the study inclusion. They were excluded if they had self-reported hypoglycemia unawareness or were using an insulin pump with predictive low glucose suspend feature.

Data Collection

The study survey was given to the eligible participants at the outpatient clinic at Copenhagen University Hospital Hvidovre, Denmark. The investigators contacted them afterwards by phone, to give more detailed information about the study and how to fill in the survey sheets. The investigators followed a structured list when giving the study information to minimize the influence of investigators’ treatment favor.

Participants were instructed to register every mild hypoglycemia event (sensor or blood glucose ≤ 3.9 mmol/l, symptoms of mild hypoglycemia, or any attempt to avoid hypoglycemia) for 2 weeks, regardless of the number of events in the survey period. For each event, participants indicated whether they preferred to take glucose orally or inject glucagon subcutaneously with a mini-dose pen if it had been available. Participants were advised to note their preference immediately after treating the mild hypoglycemic event. In total, participants answered 11 questions for each hypoglycemia event. They registered: (1) the date and time of the hypoglycemia event, (2) if they were awake or asleep immediately before the event, (3) the suspected reason for hypoglycemia (unknown, exercise, insulin, or other), (4) the sensor and/or blood glucose level, (5) whether they preferred glucagon (if it had been available) or orally administered glucose to treat the event, (6) in case of glucagon, how many units of glucagon they would use to treat the event (participants were told that one unit would raise the blood glucose level by 2.3 mmol/l, two units by 4.0 mmol/l, and three units by 5.0 mmol/l), (7) what food or drink they consumed to treat or avoid the event, (8) the carbohydrate content of the food or drink consumed, (9) if an insulin pump user, whether they stopped or reduced their basal insulin rate, (10) if they injected insulin for any extra carbohydrates and noted the amount of insulin in units, and (11) the glucose level 1 h after the hypoglycemia event.

After the registration period, the participants returned the surveys to the investigators using postage-paid return envelopes.

This study was approved by the Regional Committee on Health Research Ethics (H-15008077) and by the Danish Data Protection Agency (2012-58-0004). The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Statistical Analysis

Because this was an explorative study, no power calculations was used to estimate the sample size needed. Dichotomous outcomes are reported as percentage while continuous data are presented as mean ± SD. For the dichotomous outcomes over the 2-week survey period, a repeated measurement logistic regression analysis with participants as a random effect was used. This model allowed one to account for the individual responses, as some of the participants strictly preferred one intervention, and the number of individual interventions during the survey period. Data were analyzed using SAS Enterprise Guide 7.11 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Among the participants in the outpatient clinic from November 2015 to January 2017, 101 participants were asked to participate and 51 completed the study by filling out and returning the survey. Of the 50 non-participants, 34 did not respond after several attempts to contact them, five had too few hypoglycemia events according to the inclusion criteria before the start of the study, and 11 did not want to participate because of the lack of time. The 51 participants (13 men) were either pump users (30) or pen users (21), were 43.6 ± 12.5 years of age with HbA1c of 7.3 ± 0.7% (57 ± 8 mmol/mol), and had BMI of 24.9 ± 3.0 kg/m2.

Hypoglycemia Events

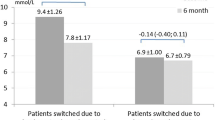

Participants reported an average of 10 (range 3–23) mild hypoglycemia events during the 2-week survey period. In total, 514 mild hypoglycemia events were recorded, and participants preferred glucagon in 58% of the events and orally administered glucose in 42% of the events (p > 0.05). Further, no difference in the preference was seen when correcting for possible causes of the event (exercise, overdosing), sex, or insulin therapy (pen or pump users) (Table 1). Twelve percent of the participants (three women and three men) had no desire to use glucagon as a treatment option for any of the hypoglycemia events they reported.

For every mild hypoglycemia event, participants noted the actual carbohydrate intake used for the rescue. On average 25 ± 17 g carbohydrate per event was consumed when subcutaneously administered glucagon was the preferred option for the treatment of mild hypoglycemia.

Of the total events, 8% did not report the amount of carbohydrate consumed to treat their mild hypoglycemia. Among the remaining, 65% of participants consumed less than 25 g carbohydrate without insulin use, 22% consumed more than 25 g carbohydrate with extra meal insulin, and 13% consumed more than 25 g carbohydrate without extra insulin (Table 2).

For around 12% of the events the blood glucose level was not reported 1 h after treatment. Among the remaining, 77% obtained optimal glucose level (3.9–10 mmol/l), 9% were still hypoglycemic, and 14% were hyperglycemic (Table 2).

Discussion

In this event-driven prospective survey, we found that in 58% of the hypoglycemic events participants indicated that they would have preferred to use subcutaneously administered glucagon rather than orally administered glucose if it had been available. The treatment preferences did not change significantly when correcting for sex, insulin treatment modality, or possible causes of the hypoglycemia event.

We observed that if low-dose glucagon had been a treatment option, it could on average have replaced 25 g carbohydrate per event. Glucagon may therefore, as an alternative to orally administered glucose for hypoglycemia treatment, reduce the overall calorie intake and potentially prevent weight gain. Additionally, previous studies have shown that glucagon reduces calorie intake by increasing satiety as well as increasing energy expenditure [13, 14]—all effects that may be beneficial for individuals with type 1 diabetes trying to keep optimal glucose control without gaining body weight. Furthermore, 77% of the rescues with orally administered glucose resulted in normoglycemia after 1 h. Although the 1-h level may not capture the actual peak postprandial glucose level, we were surprised to observe that many rescues resulted in hypoglycemia (9%) in the early postprandial phase. We can speculate whether this distribution may have been improved if low-dose glucagon was used.

A recent outpatient study demonstrated that the plasma glucose response to 150 µg soluble glucagon was comparable to that of 40 g glucose taken as tabs [15]. However, several conditions may impair glucagon’s efficacy, i.e., low carbohydrate diets [16], exercise [17], ethanol intake [18], and hyperinsulinemia [19]. Therefore, if low-dose glucagon should be used in everyday treatment of mild hypoglycemia, a variable dosing regimen depending on these factors may be preferable as shown in a simulation study proposing an insulin-dependent glucagon dosing regimen for treatment of mild hypoglycemia [20].

Nonetheless, some issues should be considered when using glucagon instead of orally administered glucose. First, an injection of glucagon may be less convenient than consuming glucose orally. Second, side effects of low-dose glucagon are likely to exceed those of orally administered glucose. Lastly, use of low-dose glucagon will most probably be more expensive than orally administered glucose for mild hypoglycemia.

This event-driven survey has limitations. First, participants did not have the actual glucagon pen, but had to imagine the opportunity of using a glucagon pen. Second, there was a selection bias due to only including participants with a high frequency of hypoglycemia. However, this criterion was needed to ensure enough hypoglycemic events per participants. Third, some participants may have reported more hypoglycemic events due to, e.g., fear of hypoglycemia. We have not assessed fear of hypoglycemia. Furthermore, not all participants had tried glucagon beforehand making them unaware of its effect and may bias the actual preference of treatment for mild hypoglycemia. Fourth, although investigators were informed about the study on the basis of a structured list, the investigator may have influenced the treatment preference for the participants. Lastly, we do not have the participants’ continuous glucose monitoring (CGM) values, and thereby cannot validate if they actually had the hypoglycemic events. Therefore, the study could have been more valuable if we registered the CGM values or downloaded their meter readings. As we also defined a hypoglycemic event as any attempt to avoid hypoglycemia, individuals did not need to have sensor or blood glucose ≤ 3.9 mmol/l. Further, some individuals acknowledge hypoglycemic symptoms at higher values.

Conclusion

This event-driven survey indicates that individuals with type 1 diabetes are interested in using glucagon for mild hypoglycemia. In 58% of the hypoglycemia events, participants preferred to use subcutaneously administered glucagon versus orally administered glucose. These findings were consistent when correcting for sex, patient treatment modality, and hypoglycemia cause.

References

DCCT Research Group. Effect of intensive diabetes treatment on the development and progression of long-term complications in adolescents with insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus: Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. J Pediatr. 1994;125:177–88.

DCCT Research Group. Adverse events and their association with treatment regimens in the diabetes control and complications trial. Diabetes Care. 1995;18:1415–27.

Gubitosi-Klug RA, Braffett BH, White NH, et al. Risk of severe hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetes over 30 years of follow-up in the DCCT/EDIC study. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:1010–6.

Beck RW, Tamborlane WV, Bergenstal RM, Miller KM, DuBose SN, Hall CA. The T1D exchange clinic registry. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2012;97:4383–9.

Fulcher G, Singer J, Castañeda R, et al. The psychosocial and financial impact of non-severe hypoglycemic events on people with diabetes: two international surveys. J Med Econ. 2014;17:751–61.

Conway B, Miller RG, Costacou T, et al. Temporal patterns in overweight and obesity in type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2010;27:398–404.

Fullerton B, Jeitler K, Seitz M, Horvath K, Berghold A, Siebenhofer A. Intensive glucose control versus conventional glucose control for type 1 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;2:CD009122.

Delahanty LM, Halford BN. The role of diet behaviors in achieving glycemic control intensively treated patients in the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Diabetes Care. 1993;16:1453–8.

Miller KM, Foster NC, Beck RW, et al. Current state of type 1 diabetes treatment in the US: updated data from the T1D exchange clinic registry. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:971–8.

Foster NC, Beck RW, Miller KM, et al. State of type 1 diabetes management and outcomes from the T1D exchange in 2016–2018. Diabetes Technol Ther. 2019;21(2):66–72.

Minges KE, Whittemore R, Weinzimer SA, Irwin ML, Redeker NS, Grey M. Correlates of overweight and obesity in 5529 adolescents with type 1 diabetes: the T1D Exchange Clinic Registry. Diabet Res Clin Pract. 2017;126:68–78.

Ranjan A, Schmidt S, Madsbad S, Holst JJ, Nørgaard K. Effects of subcutaneous, low-dose glucagon on insulin-induced mild hypoglycaemia in patients with insulin pump treated type 1 diabetes. Diabet Obes Metab. 2016;18:410–8.

Chakravarthy M, Parsons S, Lassman ME, et al. Effects of 13-hour hyperglucagonemia on energy expenditure and hepatic glucose production in humans. Diabetes. 2017;66:36–44.

Geary N, Kissileff HR, Pi-Sunyer FX, Hinton V. Individual, but not simultaneous, glucagon and cholecystokinin infusions inhibit feeding in men. Am J Physiol. 1992;262:975–80.

Rickels MR, DuBose SN, Toschi E, et al. Mini-dose glucagon as a novel approach to prevent exercise-induced hypoglycemia in type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:1909–16.

Ranjan A, Schmidt S, Damm-Frydenberg C, et al. Low-carbohydrate diet impairs the effect of glucagon in the treatment of insulin-induced mild hypoglycemia: a randomized crossover study. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:132–5.

Steineck IIK, Ranjan A, Schmidt S, Clausen TR, Holst JJ, Nørgaard K. Preserved glucose response to low-dose glucagon after exercise in insulin-pump-treated individuals with type 1 diabetes: a randomised crossover study. Diabetologia. 2019;62(4):582–92.

Ranjan A, Nørgaard K, Tetzschner R, et al. Effects of preceding ethanol intake on glucose response to low-dose glucagon in individuals with type 1 diabetes: a randomized, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Diabetes Care. 2018;41:797–806.

Bakhtiani PA, El Youssef J, Duell AK, et al. Factors affecting the success of glucagon delivered during an automated closed-loop system in type 1 diabetes. J Diabetes Complicat. 2014;1964:2010–5.

Ranjan A, Wendt SL, Schmidt S, et al. Relationship between optimum mini-doses of glucagon and insulin levels when treating mild hypoglycaemia in patients with type 1 diabetes—a simulation study. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol. 2018;122(3):322–30.

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to the study participants.

Funding

This work was funded by a research grant from the Copenhagen University Hospital Hvidovre and by the Danish Diabetes Academy supported by the Novo Nordisk Foundation. No Rapid Service Fee was received by the journal for the publication of this article.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Disclosures

Signe Schmidt has served on the continuous glucose monitoring advisory board for Roche Diabetes Care and as a consultant for Unomedical. Kirsten Nørgaard serves as adviser to Medtronic, Abbott, Sanofi, and Novo Nordisk, owns shares in Novo Nordisk, has received research grants from Novo Nordisk, Medtronic, Zealand Pharma, and Roche, and has received fees for speaking from Medtronic, Roche, Rubin Medical, Sanofi, Zealand Pharma, Novo Nordisk, and Bayer. Rikke Tetzschner and Ajenthen G. Ranjan have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This study was approved by the Regional Committee on Health Research Ethics (H-15008077) and by the Danish Data Protection Agency (2012-58-0004). The study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Informed consent was obtained from all patients for being included in the study.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.9862100.

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Tetzschner, R., Ranjan, A.G., Schmidt, S. et al. Preference for Subcutaneously Administered Low-Dose Glucagon Versus Orally Administered Glucose for Treatment of Mild Hypoglycemia: A Prospective Survey Study. Diabetes Ther 10, 2107–2113 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-019-00696-x

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-019-00696-x