Abstract

Introduction

An analysis was conducted to estimate the economic burden of insulin-related hypoglycemia in adults in Spain, derived from a novel concept developed for the UK known as the Local Impact of Hypoglycemia Tool.

Methods

Costs per severe and non-severe hypoglycemic episode were calculated for patients with type 1 diabetes (T1DM) and type 2 diabetes (T2DM). The costs per episode were applied to the population of adults with T1DM and T2DM using insulin in Spain according to the number of severe and non-severe episodes experienced per year. Costs were calculated using Spanish-specific resource costs and published values for resource utilization, including ambulance, accident and emergency (A&E) department, hospitalization, healthcare professional visits, and extra self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) tests used in the week following the episode. A one-way sensitivity analysis on all model inputs was then performed.

Results

The cost of insulin-related hypoglycemia in Spain is estimated as €662.0 m per year, €292.6 m of which is due to severe episodes and €369.4 m to non-severe episodes. The cost per episode varies from €1.25 for patients with T1DM and €1.48 for patients with T2DM for a non-severe episode where extra SMBG testing after the episode is the only action taken, to €4378.22 for T1DM and €3005.74 for T2DM for a severe episode that was treated in hospital and requires an ambulance, A&E visit, hospitalization, and a diabetes specialist visit. A reduction in severe and non-severe hypoglycemia rates of just 20% could lead to considerable cost savings of €284,925 per 100,000 general population.

Conclusion

This analysis highlights the substantial economic burden of hypoglycemia in Spain, and gives budget holders the ability to assess the costs of new treatments or patient education programs in relation to the potential cost savings due to lower hypoglycemia rates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic condition in which patients have elevated levels of blood glucose [1]. The prevalence of known diabetes in Spain is 7.8%, with a further 6.0% estimated to have unknown diabetes, as reported by a population-based survey conducted in 2009–2010 in Spain (the Di@bet.es study) with 5072 adult participants [2].

There are two main types of diabetes, type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM) and type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). T1DM, characterized by the inability to produce insulin, usually presents abruptly in childhood/adolescence, whereas T2DM, characterized by insulin resistance and/or deficiency, usually develops more gradually in later life and is associated with excess weight and obesity [1]. Approximately 90% of people with diabetes have T2DM and 10% have T1DM [1].

Since people with T1DM are unable to produce insulin, all individuals with the condition require exogenous insulin. However, T2DM is a progressive disease, and so not all patients will require insulin therapy at first and treatment is usually intensified over time. Guidelines for T2DM from the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD) recommend initial treatment with metformin, before intensifying treatment to dual therapy and triple therapy with other oral antidiabetic medications [OADs; sulfonylureas, thiazolidinediones, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP-4-Is) and/or sodium glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT2-Is)], injectable non-insulin medications [glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs)], and/or basal (long-acting) insulin [3]. Eventually all patients are likely to require insulin therapy, with intensification from basal insulin to a basal-bolus regimen, where basal insulin is combined with a rapid-acting insulin at mealtimes [3]. Similarly, guidelines for T2DM from the International Diabetes Federation (IDF) recommend initiating therapy with metformin, before adding a sulfonylurea, an α-glucosidase inhibitor, a DPP-4I, or a thiazolidinedione when intensification is necessary [4]. Recommendations for third-line treatment include initiating insulin, adding a third OAD, and adding a GLP-1 RA. Insulin therapy should be initiated with a basal insulin or premix insulin, and mealtime insulin should be added when intensification is necessary. Both the ADA/EASD and IDF guidelines recommend intensifying treatment if glycemic control has not been achieved after 3 months of therapy [3, 4]. In Spanish guidelines for the management of hypoglycemia in diabetes, metformin is recommended as a first option partly due to its low hypoglycemia risk, and basal insulin analogues are recommended as subcutaneous therapy to decrease the risk of hypoglycemia, particularly nocturnal hypoglycemia [5].

Hypoglycemia occurs when glucose levels are low, and hypoglycemia is a common side effect of antidiabetic medication, especially insulin. Symptoms include anxiety, palpitations, and confusion as well as, in more severe cases, seizure, coma, and death [6]. Hypoglycemia can be broadly defined as severe, when the episode requires the assistance of another individual (e.g., from a family member, friend, caregiver, or medical professional), or non-severe, when the episode is self-treated [7]. A questionnaire-based study in people with diabetes in Spain reported that people with T1DM experience an average of 0.9 severe and 88.0 non-severe hypoglycemic episodes per year, and people with insulin-treated T2DM experience an average of 0.32 severe and 27.2 non-severe episodes per year [8].

Hypoglycemia not only imposes a burden on the patient but also results in considerable healthcare costs. Treatment for hypoglycemia can include the administration of carbohydrates (e.g., a snack or sweet drink), glucose or glucagon, while severe episodes can result in ambulance use, accident and emergency (A&E) treatment, and hospitalization. In addition, hypoglycemia can result in visits to a general practitioner or diabetes specialist, and additional self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) tests used to assess blood glucose levels following a hypoglycemic episode. These costs have previously been estimated for the UK and Denmark using the Local Impact of Hypoglycemia Tool (LIHT) [9, 10]. The aim of this study was to use the LIHT to estimate the cost of insulin-related hypoglycemia in Spain, and to identify the potential cost savings associated with a reduction in hypoglycemia rates.

Methods

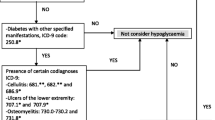

The LIHT is an economic model that was developed for the UK and is designed to assess the financial impact of insulin-related hypoglycemia in a given population using population-specific inputs for prevalence, hypoglycemia rates, costs, and resource utilization. This analysis used Spanish-specific inputs to estimate the economic burden of insulin-related hypoglycemia in Spain. The LIHT methodology has been described previously [9]. Briefly, the costs of severe and non-severe episodes in T1DM and T2DM were estimated using Spanish unit costs and published utilization values; these costs were then applied to published hypoglycemia rates among the relevant population (Fig. 1). A one-way sensitivity analysis on all model inputs was performed with the input variation set at ±20%. Analyses were performed on a sample population of 100,000 in which the rates of severe and non-severe hypoglycemia were reduced, both separately and in combination. The rates for both severe and non-severe hypoglycemia were varied in separate sensitivity analyses to illustrate the variation in budget impact due to potential differences in the prevalence of hypoglycemia. The potential impact of the use of glucose and glucagon treatment was also examined.

This article does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Data Inputs

The population of Spain as reported on 1 July 2016 was 46,468,102, of which 38,128,226 were adults [11]. The prevalence of known diabetes in Spain is 7.8% [2], of which 10% are assumed to have T1DM (297,400 people) and 90% T2DM (2,676,601 people) [1]. This study was designed to estimate the costs of insulin-related hypoglycemia; it was assumed that all people with T1DM and 17.28% of people with T2DM (462,517 people) were receiving insulin [12, 13].

A questionnaire-based study of 630 insulin-treated patients with diabetes in Spain [8] reported that people with T1DM experienced an average of 0.9 severe and 88.0 non-severe hypoglycemic episodes per year. People with T2DM were divided into different subgroups based on insulin regimen, and a weighted average of these subgroups showed that 0.32 severe and 27.2 non-severe episodes were experienced per year by people with T2DM.

Severe hypoglycemic episodes can either be treated in hospital by a medical professional or at home/work by a family member, friend, or colleague. A survey of people with diabetes in three European countries found that, in Spain (n = 224), 66.7% of severe hypoglycemic episodes in people with T1DM and 64.3% in people with T2DM were treated in hospital [14]. An economic study in Spain estimated that 83% of severe episodes in people with T2DM treated in hospital required an ambulance [15]. There was no equivalent value available for people with T1DM in Spain; therefore, this was obtained from an international meta-analysis of trials involving more than 8000 participants [16]. Of severe episodes that required medical assistance in people with T1DM, 81.8% required an ambulance. The same questionnaire-based study that reported hypoglycemia rates also reported emergency hospital visits for severe episodes (30% for T1DM and T2DM), hospitalization for severe episodes (16% for T1DM and 25% for T2DM), and general practitioner (GP) visits (12%) and diabetes specialist visits (14%) following a severe episode [8, 17].

For non-severe episodes, a weighted average of daytime and nocturnal episodes from the same study showed that 8.9% of people with T1DM and 20.0% of people with T2DM visited a healthcare professional following the episode [8]. This was conservatively assumed to refer to a GP visit rather than a visit to a diabetes specialist.

Spanish guidelines for the management of hypoglycemia recommend SMBG testing when hypoglycemia is suspected and after treatment until normal blood glucose levels have been restored [5]. The same questionnaire-based study that informed the hypoglycemia rates for this analysis reported that, in the 7 days following a non-severe episode, patients with T1DM used an average of 5.0 extra SMBG tests and patients with T2DM used an average of 5.9 extra tests [8]. There were no equivalent data identified for severe episodes; therefore, the values for non-severe episodes were assumed to also apply to severe episodes. This is also a conservative assumption, since it is likely that more SMBG tests would be used following a severe episode compared with non-severe.

Hypoglycemic episodes are treated with carbohydrates (e.g., a snack or sweet drink), glucose, or glucagon. Spanish guidelines for the management of hypoglycemia recommend treatment with 15 g glucose in conscious patients, which should be repeated after 15 min if an SMBG measurement shows persistent hypoglycemia [5]. A slow release carbohydrate should also be taken once blood glucose levels have returned to normal to prevent repeat hypoglycemia. Subcutaneous glucagon is recommended in unconscious patients [5]. For severe episodes treated in hospital, the cost of treatment (glucose or glucagon) was assumed to be included in the ambulance cost, A&E tariff, or hospitalization tariff, and was therefore not included to avoid double counting. For severe episodes treated at home/work and non-severe episodes, no data on utilization of treatment were identified; therefore, utilization values for glucose and glucagon were conservatively set to zero.

A summary of the treatment pathway and data inputs for the model are shown in Fig. 2.

Costs

Cost inputs for most healthcare resources were obtained from a cost analysis conducted in Spain on an ad hoc basis, and based upon input from health professionals [15]. For hospitalization, the cost per day was applied to an average stay of 8.0 days for patients with T1DM and 4.9 days for patients with T2DM, both of which were obtained from a retrospective study of patients with diabetes admitted to hospital for severe hypoglycemia [18]. The cost of an ambulance was obtained from the Regional Health Service of Castilla-León. The cost of an SMBG test strip was reported in the questionnaire-based study that informed many of the utilization inputs and the hypoglycemia rates [8]. The cost inputs are shown in Table 1.

Results

The cost per episode varies from €1.25 to €4378.22 for T1DM and from €1.48 to €3005.74 for T2DM, with the lower cost being a non-severe episode where extra SMBG testing after the episode is the only action taken, and the higher cost being a severe episode that is treated in hospital and requires an ambulance, an A&E visit, hospitalization, and a diabetes specialist visit (Table 2). The variation in cost of the episode is dependent on the utilization of each individual healthcare resource by each patient, and some individuals will utilize particular aspects of the Spanish healthcare system far more than others. As shown above, the cost of a hypoglycemic episode can vary widely, and an average cost per severe and non-severe episode for patients with T1DM and T2DM can be calculated across the population of interest.

The average cost per episode is calculated as €716.82 for severe and €7.09 for non-severe for T1DM, and €680.49 and €14.61 for severe and non-severe, respectively, for T2DM (Table 2). Unsurprisingly, the majority of the cost for severe episodes consists of hospitalization and ambulance use.

The cost breakdown for the average cost per episode is shown in Fig. 3.

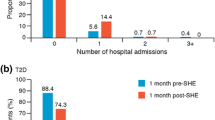

The estimated total cost of insulin-related hypoglycemia in adults in Spain is €662.0 million, €292.6 million of which is due to severe hypoglycemic episodes and €369.4 million to non-severe episodes (Table 3). The corresponding cost for a sample general population of 100,000 is €1.425 million, of which €629,600 is attributable to severe and €795,000 to non-severe episodes.

A one-way sensitivity analysis on all model inputs was performed with the input variation set at ±20%. The most influential variables are presented in Fig. 4.

A reduction in hypoglycemia of 10–50% has been shown on switching patients from NPH insulin to insulin analogues, and in turn from older insulin analogues to newer insulin analogues [19,20,21,22]. Therefore, sensitivity analyses were performed on a sample general population of 100,000 in which the rates of severe and non-severe hypoglycemia were reduced by this amount, both separately and in combination (Tables 4, 5). Results show that by reducing hypoglycemia rates by just 20%, there is a cost saving of €125,928 in a sample general population of 100,000 for severe episodes, €158,997 for non-severe episodes, and €284,925 for both.

The rates for both severe and non-severe hypoglycemia were varied in separate sensitivity analyses (Tables 5, 6) to illustrate the variation in budget impact due to potential differences in the prevalence of hypoglycemia. A literature review found that the prevalence of diabetes in Spain varies greatly among different studies and between different regions [23]. The prevalence of T2DM was found to range from 4.8% to 18.7% and the prevalence of T1DM from 0.08% to 0.2%. Therefore, the overall diabetes prevalence was varied between 4.9% and 18.9% for a sample general population of 100,000 in order for budget holders to estimate the cost of hypoglycemia in a specific region according to that region’s prevalence. Results show that the total cost of hypoglycemia ranges from €894,956 to €3.452 million (Table 6).

To analyze the potential impact of the use of glucose and glucagon treatment, the average utilization and cost of the inputs used in the UK and Danish LIHTs were calculated and applied as an estimate for Spain in the scenario analysis. The results of this scenario analysis are shown in Table 7.

Discussion

This study highlights the substantial cost burden of hypoglycemia in Spain for insulin-treated adults with diabetes. The cost of non-severe hypoglycemia in particular is often overlooked and underestimated; however, this study estimates the overall cost of non-severe episodes to be greater than the cost of severe episodes. This is due to the much higher rate of non-severe hypoglycemia compared with severe, despite the considerably lower cost of an average non-severe episode compared with severe. The costs associated with people with T1DM are higher than those with T2DM, despite the fact that there are approximately 50% more people with T2DM receiving insulin than people with T1DM. This is largely due to a higher rate of both severe and non-severe hypoglycemic episodes in people with T1DM, but also to the fact that a slightly higher percentage of severe episodes are treated in hospital rather than at home/work in T1DM. In addition, people with T1DM are 36% less likely to need hospitalization for a severe episode; however, if hospitalization is required, the average length of stay is nearly twice as long as for people with T2DM.

These results enable healthcare budget holders to estimate the cost of hypoglycemia in Spain or in a specific hospital or region, for example. In addition, the results enable decision makers to offset the cost of different insulin therapies with a more favorable hypoglycemia profile, as recommended in Spanish guidelines for hypoglycemia management [5], and patient education programs with the decrease in costs associated with an expected reduction in hypoglycemia rates.

Varying by ±20% the cost of a GP visit, the percentage of severe episodes treated in hospital for T1DM, and the percentage utilization for GP visits for a non-severe episode in T2DM had the largest effects on the overall results and therefore were the inputs that showed the greatest uncertainty. The cost and utilization of HCP visits (GP and diabetes specialist) were also among the main drivers of the model in an analysis conducted in the UK and Denmark [9, 10]. In addition, a study (SECCAID) that estimated the costs of diabetes in Spain reported that 28% of the total corresponds to primary care [24], further supporting the fact that GP costs are an important part of the cost of diabetes and its associated complications.

There are a number of limitations with the analysis; however, all assumptions are considered conservative and therefore the overall results are unlikely to be overestimated. General limitations of the approach are that only insulin-related hypoglycemia, symptomatic hypoglycemia, and an adult population are considered. While hypoglycemia is most commonly associated with insulin therapy, it can also be experienced with other antidiabetic medicines, e.g., sulfonylureas and glinides [3]. It is difficult to estimate whether asymptomatic hypoglycemia incurs additional costs and, if so, how much; however, not including any cost associated with asymptomatic episodes in the default case means that these costs will not be overestimated and that this analysis will, if anything, be conservative. Asymptomatic hypoglycemia is commonly associated with impaired awareness of hypoglycemia, which was reported in 55% of subjects with T1DM and 39% of subjects with T2DM in a questionnaire-based study in Spain [8]. Based on these figures, scenario analysis showed that asymptomatic patients were assumed only to suffer a non-severe hypoglycemic event, resulting in an additional SMBG test, but not incurring the additional cost of a GP appointment as in the default case. In addition, while there are much fewer children with diabetes than adults [12] and while it is impossible to speculate as to the utilization of healthcare resources in children compared with adults, there will at least be some cost for hypoglycemia in children that will add to the economic burden of hypoglycemia calculated in this study.

There are some necessary assumptions in the model. Firstly, the use of glucose and glucagon treatment is not included as a conservative approach. For severe episodes treated in hospital, it is assumed that these costs are included in the hospitalization tariff, A&E cost, and ambulance service cost, to avoid double counting. For non-severe episodes and severe episodes treated at home/work, no data were identified on the use of glucose or glucagon, and so these costs are not included; however, it is likely that glucose or glucagon would be used in the treatment of some (unknown) proportion of these hypoglycemic episodes. In an estimate of the cost of hypoglycemia in Denmark, data were available for glucose and glucagon use for severe episodes treated at home; 3.2% of episodes required glucagon, 6.8% required a glucose infusion, and 2.6% required a glucose tablet [10].

Second, no data were identified for the use of extra SMBG tests following a severe episode, and so the number used following a non-severe episode is assumed to also apply to severe episodes. This is also likely to be conservative, since patients are likely to monitor their blood glucose more closely following a severe episode than following a non-severe episode.

Third, the percentage of patients visiting a GP and diabetes specialist following a severe episode is assumed to be the same for T1DM and T2DM. The source for these data is a trial that included both patients with T1DM and patients with T2DM, in a 47:53 ratio. It has previously been reported that people with T2DM have a higher healthcare resource utilization than people with T1DM for a severe hypoglycemic episode [16], and data used in the present analysis show that a higher percentage of people with T2DM contact a healthcare professional following a non-severe hypoglycemic episode than people with T1DM [8]. Therefore, using data from a study in which approximately 50% of patients have T1DM is likely to misrepresent the true mix of patients, which is made up of only about 10% T1DM. This means that the utilization value obtained from this study is likely to be underestimated.

Fourth, a visit to a healthcare professional following a non-severe episode is assumed to be with a GP rather than a diabetes specialist, which is conservative as this is the less expensive of the two options. In addition, the cost of a hospital stay is assumed to be in a general ward rather than intensive care, which also costs the least of the two options.

Finally, it is possible that the hypoglycemia rates used in the analysis are under-reported. The study that the rates are obtained from is a questionnaire-based study that relies on patient recall. In addition, the occurrence and recurrence of hypoglycemia (particularly severe) can prevent people with diabetes from keeping or obtaining a driver’s license, particularly a commercial license [25], and so patients may not report all hypoglycemic episodes experienced for fear of losing their license.

There have been a limited number of studies reporting the cost of hypoglycemia in Spain. A survey-based study of insulin-related severe hypoglycemia in Spain in 2006–2007 [14], which informed the percentage of severe episodes treated in hospital for this analysis, estimated a cost per episode of €30 for family/domestic treatment, €246 for community HCP treatment, and €1396 for hospital HCP treatment in patients with T1DM, and €52, €371, and €1370 in patients with T2DM, respectively. An average was reported using the split between family/domestic treatment and community/hospital treatment that was also used in the present analysis, and different splits between community treatment and hospital treatment. The base case split for community/hospital of 50%/50% for T1DM and 35%/65% for T2DM gave an average cost per severe episode of €577 for T1DM and €691 for T2DM. These costs are for 2007; inflating to 2016 costs using the Spanish consumer price index [26] gives €621 for T1DM and €744 for T2DM, which are comparable to those estimated in the present analysis (€717 for T1DM and €680 for T2DM). Two other retrospective studies that calculated the cost of severe hypoglycemia, one only in patients with T1DM [27] and one only in Andalusia [28], reported a cost per episode of €239 and €702, respectively. The cost from the study in patients with T1DM is noticeably lower than that estimated in the present analysis (€808), which appears to be due to the fact that severe episodes were assumed to be treated by a family member in 75% of cases, compared with 33% in the present analysis. Another study that estimated the cost of severe hypoglycemia using experts’ opinions reported a cost per episode of just €172.33 [29] for all severe hypoglycemic episodes (not just insulin-related). However, there are a number of reasons for this difference. Again, a higher percentage of episodes were assumed to be treated by a family member (68%) than by a medical professional. In addition, for episodes that resulted in hospitalization, a stay of only 1 day was assumed, and only one extra SMBG test was assumed to be used following a hypoglycemic episode. There were also a number of acknowledged limitations with this study: experts may have non-representative experience of hypoglycemia; experts may find it difficult to correctly estimate average resource consumption; experts do not treat family-treated episodes (by definition); and data were not always available for resource use in Spain, so data from Greece or an average from other countries was used instead.

In contrast to the two studies reporting a lower cost per severe hypoglycemic episode [14, 29], a review article was also identified that reported the cost for a severe episode as €3597 and estimated the cost of a non-severe episode as between €30 and €35. These costs are both higher than the estimates in the present analysis, with the severe cost substantially so. In fact, the cost reported for a severe episode is in the same range as the highest cost of a severe episode calculated in the present analysis using maximum resource utilization (€4378 for T1DM and €3006 for T2DM).

Another review article [30] estimated the total direct cost of diabetes in Spain in 2009 to be €5.1 billion, meaning that the cost of hypoglycemia, as calculated in the present analysis, represents 13% of the total cost of diabetes, which is a substantial proportion.

For comparison, the cost of hypoglycemia has also been estimated using the LIHT for the UK [9] and for Denmark [10]. The results have been converted to Spanish Euros using purchasing power parities to directly compare and are shown alongside the results for the present analysis in Table 8.

The cost per severe episode is substantially higher in Spain than in Denmark and the UK, and the cost per non-severe episode is higher than in Denmark, but lower than the UK for patients with T1DM and comparable for patients with T2DM. The higher cost for severe episodes is due to a number of reasons. The main difference is that there are a much higher percentage of patients treated in hospital for severe episodes in Spain (66.7% and 64.3% for T1DM and T2DM, respectively) than in Denmark (20.3% for both T1DM and T2DM) or the UK (23% for T1DM and 53% for T2DM). The percentage of episodes resulting in hospitalization is lower in Denmark (4.4%) than in Spain (16% for T1DM and 25% for T2DM) but comparable to the UK (21%). Ambulance use and A&E treatment are similar in Spain and Denmark, but are slightly higher in the UK. The percentage of diabetes specialist visits following a severe episode treated in hospital is also higher in the UK and Denmark than in Spain. In terms of costs, ambulance, A&E, and hospitalization are all more expensive in Spain than in the UK and Denmark (when costs are converted into Spanish EUR). The cost of a diabetes specialist visit is comparable in Spain, the UK, and Denmark.

For non-severe episodes, the percentage of GP visits is higher in Spain than in Denmark, but is lower in Spain than the UK for T1DM and comparable to the UK for T2DM. The number of extra SMBG tests used following a hypoglycemic episode is similar in Spain and the UK, but lower in Denmark. Costs for a GP visit were also similar in Spain and the UK but lower in Denmark, and the cost of SMBG tests was similar in Spain and the UK but higher in Denmark.

The cost of severe hypoglycemia per 100,000 general population is nearly 20-fold higher in Spain than in Denmark, but is comparable to the UK (although slightly higher). The substantially higher cost in Spain than in Denmark is due to not only a higher cost per episode but also a higher prevalence of diabetes (7.8% vs. 5.7%) and higher rates of severe hypoglycemia for both patients with T1DM (0.9 vs. 0.6 episodes per year) and patients with T2DM (0.32 vs. 0.1 episodes per year). The cost per severe episode and the diabetes prevalence are both higher in Spain than in the UK (prevalence 7.8% vs. 6.0%), but this is offset by a lower severe hypoglycemia rate for both patients with T1DM (0.9 vs. 3.2 episodes per year) and patients with T2DM (0.32 vs. 0.7 episodes per year).

The cost of non-severe hypoglycemia per 100,000 is higher in Spain than in both Denmark (approximately 6-fold) and the UK (approximately 3-fold). The rate of non-severe hypoglycemia is similar in Spain and Denmark for both patients with T1DM (88.0 vs. 98.6 episodes per year) and patients with T2DM (27.2 vs. 27.4 episodes per year), but the diabetes prevalence and cost per non-severe episode are both higher in Spain. For the UK the cost per non-severe episode is lower in Spain for patients with T1DM and comparable for patients with T2DM, and the higher overall cost is due to a higher diabetes prevalence in Spain and a much higher non-severe hypoglycemia rate for both patients with T1DM (88.0 vs. 29.0 episodes per year) and patients with T2DM (27.2 vs. 10.2 episodes per year).

These differences in costs combine to mean that the total cost of hypoglycemia per 100,000 general population in Spain is calculated as 9.00 times the cost in Denmark and 2.03 times the cost in the UK, and is a substantial cost for people with insulin-treated diabetes that should not be ignored.

Conclusions

The cost of hypoglycemia is significant, representing an estimated 13% of the total cost of diabetes. It is often underestimated, but has been shown to be higher in Spain than in both the UK and Denmark. The results of this analysis may aid clinicians and budget holders in their choices regarding insulin treatments, providing the ability to offset the cost of a new drug or patient education program with the expected reduction in hypoglycemia. This provides the opportunity to explore how reducing hypoglycemia can improve the quality of diabetes care for patients and result in substantial budget savings.

Change history

01 September 2017

An erratum to this article has been published.

References

International Diabetes Federation (IDF). About diabetes. http://www.idf.org/about-diabetes. Accessed Jan 2017.

Soriguer F, Goday A, Bosch-Comas A, et al. Prevalence of diabetes mellitus and impaired glucose regulation in Spain: the Di@bet.es Study. Diabetologia. 2012;55:88–93.

Inzucchi SE, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB, et al. Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2015: a patient-centered approach: update to a position statement of the American Diabetes Association and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:140–9.

International Diabetes Federation (IDF) Clinical Guidelines Task Force. Global guideline for type 2 diabetes; 2012. http://www.idf.org/sites/default/files/IDF-Guideline-for-Type-2-Diabetes.pdf. Accessed Jan 2017.

Mezquita-Raya P, Reyes-Garcia R, Moreno-Perez O, et al. Position statement: hypoglycemia management in patients with diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Mellitus Working Group of the Spanish Society of Endocrinology and Nutrition. Endocrinol Nutr. 2013;60:517 e1–18.

Cryer PE, Davis SN, Shamoon H. Hypoglycemia in diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2003;26:1902–12.

Brod M, Christensen T, Thomsen TL, Bushnell DM. The impact of non-severe hypoglycemic events on work productivity and diabetes management. Value Health. 2011;14:665–71.

Orozco-Beltran D, Mezquita-Raya P, Ramirez de Arellano A, Galan M. Self-reported frequency and impact of hypoglycemic events in Spain. Diabetes Ther. 2014;5:155–68.

Parekh WA, Ashley D, Chubb B, Gillies H, Evans M. Approach to assessing the economic impact of insulin-related hypoglycaemia using the novel Local Impact of Hypoglycaemia Tool. Diabet Med. 2015;32:1156–66.

Hoskins N, Tikkanen CK, Pedersen-Bjergaard U. The economic impact of insulin-related hypoglycemia in Denmark: an analysis using the Local Impact of Hypoglycemia Tool. J Med Econ. 2017;20(4):363–70.

Instituto Nacional de Estadistica. 2012. http://www.ine.es/ine/planine/informe_anual_2012.pdf. Accessed 23 June 2017.

International Diabetes Federation (IDF). Diabetes Atlas, 7th ed.; 2015. http://www.diabetesatlas.org/. Accessed Jan 2017.

LPD TAM Dec 11, IMS sales TAM Dec 11, di@bet.es, Diabetes tracking Gfk; 2012. Data on file.

Hammer M, Lammert M, Mejías SM, Kern W, Frier BM. Costs of managing severe hypoglycaemia in three European countries. J Med Econ. 2009;12:281–90.

Rubio-Terres CG, Perez JN, Alvarez ED, Mira SA, Magana A. Impacto económico y sanitario de las hipoglucemias nocturnas asociadas al tratamiento de la diabetes mellitus tipo 2 con insulina glargina o insulina NPH. Av Diabetol. 2013;29:19–26.

Heller SR, Frier BM, Herslov ML, Gundgaard J, Gough SC. Severe hypoglycaemia in adults with insulin-treated diabetes: impact on healthcare resources. Diabet Med. 2016;33:471–7.

Ramirez de Arellano A. The patient-reported health related effects and economic impact of hypoglycaemic events in Spain. In: Oral presentation at XXXIII Jornadas de Economia de la Salud, Santander; 2013.

Barajas Galindo DE, Alejo Ramos M, Villar Taibo R, Ballesteros Pomar MD, Cano Rodriguez I, Vidal Casariego A. Hospitalizaciones por hipoglycemia grave en diabeticos en el complejo asistencial: Frecuencia y caracteristicas de los pacientes. In: Poster presentation at XXVI Congreso Nacional de la Sociedad Española de Diabetes, Valencia; 2015.

Horvath K, Jeitler K, Berghold A, et al. Long-acting insulin analogues versus NPH insulin (human isophane insulin) for type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;2007:CD005613.

Monami M, Marchionni N, Mannucci E. Long-acting insulin analogues vs. NPH human insulin in type 1 diabetes. A meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2009;11:372–8.

Lane WBT, Gerety G, Gumprecht J, Philis-Tsimikas A, Hansen CT, Nielsen TSS, Warren M. SWITCH 1: reduced hypoglycemia with insulin degludec (IDeg) versus insulin glargine (IGlar), both U100, in patients with T1D at high risk of hypoglycemia: a randomized, double-blind, crossover trial. In: Poster presented at the American Diabetes Association, 76th Annual Scientific Sessions, New Orleans; 2016.

Wysham CBA, Chaykin L, de la Rosa R, et al. SWITCH 2: reduced hypoglycemia with insulin degludec (IDeg) versus insulin glargine (IGlar), both U100, in patients with T2D at high risk of hypoglycemia: a randomized, double-blind, crossover trial. In: Poster presented at the American Diabetes Association, 76th Annual Scientific Sessions, New Orleans; 2016.

Ruiz-Ramos M, Escolar-Pujolar A, Mayoral-Sanchez E, Corral-San Laureano F, Fernandez-Fernandez I. La diabetes mellitus en España: mortalidad, prevalencia, incidencia, costes económicos y desigualdades. Gac Sanit. 2006;20:15–24.

Crespo C, Brosa M, Soria-Juan A, Lopez-Alba A, López-Martínez N, Soria B. Costes directos de la diabetes mellitus y de sus complicaciones en España (Estudio SECCAID: Spain estimated cost Ciberdem-Cabimer in Diabetes). Avances Diabetol. 2013;29:182–9.

International Diabetes Federation (IDF) Europe. Driving licence and diabetes: key findings IDF Europe survey 2010. https://www.idf.org/sites/default/files/DL_report_220910.pdf. Accessed Feb 2017.

Instituto Nacional de Estadistica. Consumer price index. http://www.ine.es/jaxiT3/Tabla.htm?t=10305&L=1. Accessed Feb 2017.

Reviriego J, Gomis R, Maranes JP, Ricart W, Hudson P, Sacristan JA. Cost of severe hypoglycaemia in patients with type 1 diabetes in Spain and the cost-effectiveness of insulin lispro compared with regular human insulin in preventing severe hypoglycaemia. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62:1026–32.

Barranco RJ, Gomez-Peralta F, Abreu C, et al. Incidence and care-related costs of severe hypoglycaemia requiring emergency treatment in Andalusia (Spain): the PAUEPAD project. Diabet Med. 2015;32:1520–6.

Jakubczyk M, Lipka I, Paweska J, et al. Cost of severe hypoglycaemia in nine European countries. J Med Econ. 2016;19:973–82.

Lopez-Bastida J, Boronat M, Moreno JO, Schurer W. Costs, outcomes and challenges for diabetes care in Spain. Global Health. 2013;9:17.

OECD Data. Purchasing power parities (PPP). https://data.oecd.org/conversion/purchasing-power-parities-ppp.htm. Accessed March 2017.

Acknowledgements

This study was funded by Novo Nordisk, Crawley, UK. The study sponsor also funded article processing charges. Editorial assistance was provided by DRG Abacus and support for this assistance was funded by Novo Nordisk. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this manuscript, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given final approval for the version to be published. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Disclosures

Witesh Parekh is an employee of Novo Nordisk, UK. Antonio Ramirez de Arellano is an employee of Novo Nordisk, Spain. Pedro Mezquita Raya has received honoraria from Abbott Diabetes Care, Ascensia, Astra Zeneca, Boehringer, FAES, GSK, Janssen, Johnson & Johnson Diabetes Care, Lilly, MSD, and Novo Nordisk. Nicki Hoskins and James Baker-Knight have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethics Guidelines

This article does not contain any new studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced content To view enhanced content for this article go to http://www.medengine.com/Redeem/6F98F0600A002E4C.

An erratum to this article is available at https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-017-0293-0.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0), which permits use, duplication, adaptation, distribution, and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Parekh, W., Hoskins, N., Baker-Knight, J. et al. The Economic Burden of Insulin-Related Hypoglycemia in Spain. Diabetes Ther 8, 899–913 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-017-0285-0

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13300-017-0285-0