Abstract

Laterally and torsionally unrestrained steel I-section beams are susceptible to torsional deformations between supports; therefore, according to Part 1-1 of Eurocode 3, they need to be designed to resist lateral-torsional buckling. Eurocode’s steelwork design criteria require safety checking based on two stability interaction formulae utilizing the so-called equivalent uniform moment factors and the cross-section resistance formula that, in the case of moment gradient, refer to the beam end section. Uncoupling the beam stability resistance criterion and the cross-section resistance criterion may result in a nonuniform safety assessment of I-section beams. Finite element simulations of the beam resistance for different moment gradient ratios are performed. Verification of the buckling resistance is conducted by varying the following parameters: the slenderness ratio, the location of maximum end moments about both axes and the section depth-to-width ratio (i.e., considering rolled I- and H-sections). The variation in the accuracy of the current Eurocode resistance evaluation method is identified, and an approach for a better equalization of the safety predictions is suggested by considering different values of the most important factors influencing the stability performance of steel I-section beams.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Part 1-1 of EN 1993 (2005) gives direct recommendations for the lateral-torsional buckling (LTB) of beams laterally and torsionally unrestrained between supports and under mono-axial bending about the section major axis y–y (My). This code does not, however, refer explicitly to the stability evaluation of beams subjected to biaxial bending (My and Mz, where Mz is bending about the section minor axis z–z). This case (My and Mz) is to be treated as a special case of the code’s resistance interaction formulae developed for compression and biaxial bending (N, My and Mz) when the axial force is zero.

Investigations on LTB of mono-axial major axis bending of I-sections have been well researched with regard to many factors influencing the resistance of real beams, a survey of which may be found in Trahair (1993), Trahair et al. (2008), Weiss and Giżejowski (1991) and Rykaluk (2012). An evaluation of the design rules of the biaxial bending of beam-columns is presented in Bradford (1995). The background information for the recommendations of the current Eurocode 3 (EN 1993-1-1 2005) with regard to combined compression and bending is presented in Boissonnade et al. (2004 and Greiner and Lindner (2006) and in the ECCS design manual (da Silva et al. 2010b). Further improvements for the revision of LT buckling assessment are the focus of Taras and Greiner (2010), and Greiner and Taras (2010). Recently, new methods for the design procedure of beam-columns are presented in Boissonnade et al. (2017) and Rodriguez-Gutierrez and Aristizabal-Ochoa (2017) and can be applied to the case of biaxial bending. However, investigations of the stability behaviour in the case of biaxial bending of I-sections alone are less reported in the literature; see analytical investigations reported in Baptista (2012a) on the evaluation of elastic and plastic resistances under axial force and biaxial bending of an I-section. There are more papers dealing with other section types. Research on the resistance of double symmetric rectangular hollow cross sections is presented in Baptista (2012b). In the case of angle sections, very similar surveys were provided in Vayas et al. (2009) and Aydın and Doğan (2007). This problem is a special case in which a normalized axial force is equal to zero. The examples presented in the literature are of a very clear form. An approach presented in the abovementioned papers is based on beam theory and some basic hypotheses; one hypothesis with the most far-reaching consequences states that the plastic hinge will occur in the “most stressed” cross section. The “most stressed” cross section is the one in which the combined normal stresses resulting from bending moments and compressive forces integrated over the cross-sectional area (as an absolute value) reach the maximum value. Clearly, the development of plastic hinges results from the interaction of all forces, the cross-section shape and some local phenomena, resulting for example, from boundary conditions and loading realization. Such influences are neglected in beam theory; note the need for FEM application in such cases. Therefore, the interaction of biaxial bending on the resistance curve in the case of thin-walled rectangular cross-section elements is analysed not only analytically but also numerically in papers (Kim and Wierzbicki 2000; Belingardi and Peroni 2005; Osterrieder and Kretzschmar 2006). In all stability problems, the finite element models were created from shell elements, the material was assumed to be elastic–plastic, and the obtained results were confronted with thin-walled beam theory, proving that some interesting conclusions that are contrary to the beam formulations can be drawn from the FEM analysis. Such conclusions should be verified by experimental investigations, especially in the case of aluminium extrusions, like those presented in Belingardi and Peroni (2007). For investigations related to rectangular thin-walled cross-section elements, a special stand for biaxial loading was designed to obtain a fundamental understanding of the influence of test loading conditions on element resistance. The obtained results demonstrated the element’s overall behaviour and the local phenomena accompanying the plastic hinge formation. Another experimental validation of numerical modelling was presented in the case of a steel I-cross section element bent in one plane in Yang et al. (2017). The obtained and verified results demonstrate conservative predictions of three standards: Eurocode 3, American standards and Chinese standards.

The purpose of this paper is fivefold: (1) present the background to Eurocode’s LTB formulation (da Silva et al. 2010a; Giżejowski et al. 2016b), (2) develop a FE modelling technique for the verification of the resistance criteria of imperfect beams subjected to a moment gradient for biaxial bending (mono-axial bending as a special case), (3) conduct advanced finite element simulations using GMNIA with a shell modelling technique, (4) carry out the verification exercise of Eurocode’s resistance interaction criteria, and finally (5) suggest the improvements of codification to equalize the safety assessment for different section geometry, slenderness ratio and moment gradient cases.

2 Background of Eurocode’s Formulation for Resistance Interaction Criteria for Biaxial Bending

Let us consider the buckling resistance of an imperfect beam under a combined loading condition of applied support moments (Myd,max, Myd,min) about the strong axis and (Mzd,max, Mzd,min) about the weak axis that produce the biaxial moment gradient state of stress resultants My,Ed(x) and Mz,Ed(x). Figure 1 shows the general case of the first order BMDs corresponding to the moment gradient for bending about both axes, in which the maximum values of the applied support moments Myd,max and Mzd,max for the left end. The bending moment diagrams (BMDs) referring to moment stress resultants about the section principal axes y–y and z–z may be decomposed into symmetrical and antisymmetrical diagrams.

Moment diagrams may therefore be described by the superposition of the component equations, identifying the symmetric BMD for which the end moment stress resultants are Mys,Ed and Mzs,Ed (see Fig. 1b), and the antisymmetric BMD for which the end moment stress resultants are Mya,Ed and Mza,Ed (see Fig. 1c). Thus, the first-order end moment stress resultants are as follows:

where \(M_{y,Ed,\hbox{min} } = \psi_{y} M_{y,Ed,\hbox{max} }\) and \(M_{z,Ed,\hbox{min} } = \psi_{z} M_{z,Ed,\hbox{max} }\).

The field moment relationships My,Ed(x) and Mz,Ed(x) depend upon the placement of the maximum support moment and may be written as follows:

-

for the maximum applied moment over the left support:

$$M_{y,Ed} \left( x \right) = M_{ys,Ed} + \left( {1 - \xi } \right)M_{ya,Ed} ,$$(3a)$$M_{z,Ed} \left( x \right) = M_{zs,Ed} + \left( {1 - \xi } \right)M_{za,Ed} ,$$(3b) -

for the maximum applied moment over the right support:

$$M_{y,Ed} \left( x \right) = \left( {1 - \xi } \right)M_{ya,Ed} - M_{ys,Ed} ,$$(4a)$$M_{z,Ed} \left( x \right) = \left( {1 - \xi } \right)M_{za,Ed} - M_{zs,Ed} ,$$(4b)where \(\xi = 2x/L\) is the dimensionless beam axis coordinate and L—beam length.

A number of moment gradient combinations of My,Ed(x) and Mz,Ed(x) are possible. Considering the discrete values of ψy = 1, 0 and − 1 and ψz = 1, 0 and − 1, Table 1 shows all possible combinations of the moment gradient distributions about both section principal axes. In symbols identifying the loading case, the first letter stands for a type of the first-order BMD, namely, S for symmetric (rectangular), T for triangular and A for antisymmetric (bi-triangular), while the second letter M stands for moment, and finally the last letter stands for the axis about which the bending is taking place, namely, Y for bending about the y–y axis and Z for bending about the z–z axis.

In the following section, the authors of this paper present the finite element model for the verification of Eurocode’s approach to the buckling resistance assessment of I-section beams. The finite element method is used, and at first, its accuracy is evaluated for the LTB resistance due to mono-axial bending about the y–y axis. Refinements of the geometry discretization meshing with shell finite elements are discussed. Numerical simulations are carried out using GMNIA and a nonlinear solver option available in ABAQUS/Standard (ABAQUS Theory manual 2011; ABAQUS/Standard User’s manual 2011). For biaxial bending, the interaction resistance curves from the numerical simulations, expressed in the dimensionless coordinates mby = My,Ed,max/Mby,Rk and mcz = Mz,Ed,max/Mcz,Rk [where Mby,Rk and Mcz,Rk are the characteristic lateral-torsional buckling resistance and characteristic cross-section bending resistances according to EN 1993-1-1 (2005), respectively], are expected to be nonlinear and of varying degrees, dependent upon the gradient case. The obtained numerical results are used for the verification of Eurocode’s formulation for biaxial bending and for mono-axial bending. In the case of mono-axial LTB resistance, the discrete points from the finite element simulations are compared with the corresponding Eurocode buckling curves represented in the coordinate system defined by mby and \(\overline{\lambda }_{LT,ref}\) (see explanation in Sect. 3.1). The case of out-of-plane buckling of unrestrained beams under biaxial bending may be regarded as similar to that used in Giżejowski et al. (2016c, 2017b) and for in-plane bending and compression. The similarity yields from the same number of elementary resistance ratio components to be considered (two components) and the same nature of the components (one refers to the member buckling phenomenon, and the other refers one to the yielding criterion of the most stressed section).

3 Assumptions and Numerical Model Descriptions

3.1 Material Model and I-Section Beams Considered

Typical grades of structural steel up to S 420 fulfil the minimum ductility requirements for the plastic design defined in Part 1-1 of Eurocode 3 (EN 1993-1-1 2005). The material constitutive model of all steel grades may then be approximated using an elastic–plastic model. The plastic strains are associated with the classical Huber–Mises yield condition, which is also used for plasticity detection. After yielding, the material undergoes plastically isotropic hardening, which means that in principal stress space, the yield condition is expanding to the same extent in every direction.

For the assumed material (steel S 235), three ranges are distinguished:

-

1.

The elastic range, in which the material behaviour is described by Hooke’s relationship for isotropic materials, with Young’s modulus E equal to 210 GPa and Poisson’s ratio equal to 0.3.

-

2.

The inelastic strain hardening range for strains in the interval \(\varepsilon \in \left( {\varepsilon_{y} ,\varepsilon_{u} } \right)\), where the isotropic strain hardening modulus is equal to \(\tilde{E} = {{\left( {f_{u} - f_{y} } \right)} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\left( {f_{u} - f_{y} } \right)} {\left( {\varepsilon_{u} - \varepsilon_{y} } \right)}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\left( {\varepsilon_{u} - \varepsilon_{y} } \right)}}\) and Poisson’s ratio is equal to 0.5 as a consequence of the plastic incompressibility assumption.

-

3.

The ideally plastic behaviour range for strains \(\varepsilon > \varepsilon_{u} = 0.15\), in which the yield stress fu = 1.1·fy. In that range, the hardening modulus \(\tilde{E} = 0\), but the incompressibility assumption is still valid.

The graph of uniaxial stress–strain dependence for the constitutive model assumed for the steel in this paper is presented in Fig. 2.

In the applied modelling technique, nonlinearity is taken into account in two ways. The deformation description is completed with large deformation theory (continuum solid mechanics), where the strain tensors are logarithms from the left Cauchy–Green stretch tensor. The multiplicative decomposition of the deformation gradient tensor onto elastic and plastic part is assumed. In the case of a logarithmic strain tensor, the multiplicative decomposition is equivalent to additive decomposition, which is the key feature of the applied finite element software ABAQUS/Standard. The decomposition of strains into elastic and plastic parts specifies the second nonlinearity consideration. The elasto-plasticity constitutive model with isotropic strain hardening produces the nonlinear relationship between the stress and strain tensor. The applied model with the Mises yield condition, associated plastic flow law and local loading/unloading conditions allows for the stress redistribution phenomena, which are very important, mainly when some local buckling occurs with stress concentrations.

In the present research, two I-sections representatives for the LTB problems of imperfect beams are considered, namely, the rolled H-type (wide flange HEB 300 conforming to h/b ≤ 2.0) and I-type (narrow flange IPE 500 conforming to h/b > 2.0). Both sections are of class 1 in bending according to the classification introduced in EN 1993-1-1 (2005). The buckling curves used in EN 1993-1-1 (2005) for the resistance assessment of the beams made of the I-sections mentioned above and their imperfection factors αLT are given in Table 2.

The beam lengths considered hereafter correspond to discrete values of the flexural slenderness ratio \(\overline{\lambda }_{z}\), according to EN 1993-1-1 (2005), in the range of 0.5–3.0 with an interval of 0.5 and in the range of 3.0–6.0, with an interval of 1.0 are taken into consideration. The LTB slenderness \(\overline{\lambda }_{LT}\) is defined according to EN 1993-1-1 (2005) using the critical moment Mcr calculated as presented in Giżejowski et al. (2016b). The reference lateral-torsional buckling slenderness \(\overline{\lambda }_{LT,ref}\) is calculated in the same way as \(\overline{\lambda }_{LT}\), according to EN 1993-1-1 (2005) and Giżejowski et al. (2016b), but using the critical moment Mcr,0, which refers to the LT buckling of the basic case, i.e., a perfect elastic beam under uniform bending moment about the section major axis (ψy = 1). Tables 3 and 4 show the comparison of the values of the LTB slenderness ratios \(\overline{\lambda }_{LT,ref}\) and \(\overline{\lambda }_{LT}\) for discrete values of the flexural slenderness ratio \(\overline{\lambda }_{z}\) adopted hereafter in the finite element simulations of the beam resistance of the HEB 300 and IPE 500 rolled sections. It can be seen that the slenderness ratio \(\overline{\lambda }_{LT}\) is very dependent upon the moment gradient ratio; this must be considered when analysing the results of numerical simulations for a different range of moment gradient ratios (Gizejowski and Stachura 2017).

3.2 Finite Elements, Load Transfer and Boundary Conditions

A detailed sensitivity analysis in the case of buckling FEM modelling with 3D elements is presented in Kala and Valeš (2017) and Kala (2015). The results obtained from this analysis for the same support conditions showed that the type and value of the geometrical imperfection and the value of the yield stress are among the most important factors. Numerical simulations of LT buckling using 3D brick elements in comparison to shell and beam elements were also presented in Giżejowski et al. (2016c). The conclusion is that the application of such a modelling technique for the resistance evaluation of rolled I-sections leads to time-consuming and costly simulations, especially if a rational finite element aspect ratio is maintained for the slender elements, while the accuracy of the buckling strength predictions and the equilibrium path estimations remain practically the same when obtained with the use of the shell finite element modelling technique. Hence, shell finite element modelling of the behaviour of I-section beams is considered in this paper, using linear 4-node thin shell elements S4R (hereafter called SM).

Only simple boundary conditions, hereafter called the fork conditions, are considered in the beam model in this study. Details of the left-hand side (LHS) support boundary conditions are shown in Fig. 3. Figure 3a presents the fully restrained beam axis translations (uC, vC, and wC) and the rotation θxC about the longitudinal axis. The rotations about the y–y and z–z axes, θzC and θyC as well as the warping of section plate elements are free (free flange rotations \(\pm \;\theta_{zf}\) correspond to the warping degree of freedom \({{{\text{d}}\theta_{xC} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{{\text{d}}\theta_{xC} } {{\text{d}}x}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {{\text{d}}x}}\) in the beam model). The subscript C refers to the cross section gravity centre that, for bisymmetrical I-sections, coincides with the shear centre S. At the right-hand side (RHS) support, the longitudinal translation uC is allowed; this is the only difference in the boundary conditions at both supports. Moment actions applied to the end sections correspond to the rotational degrees of freedom about the y–y and z–z axes.

Special care has to be paid in modelling the boundary and load transfer conditions for the SM simulations. To compare the results from the BM and SM simulations, the boundary conditions and load application conditions should be the same in both modelling techniques. In the case of the FE BM (Fig. 3a), warping is allowed through the application of the B32 OS type of finite elements (open section), whereas in the case of the FE SM (Fig. 3b), the warping is possible due to the use of different modelling tools available in the ABAQUS/Standard software. Figure 3b shows the details of the SM modelling at the LHS support. The developed model of the three rigid subcontours for both flanges and the web allows for a convenient application of the action moments. The moment My,Ed is to be applied at the centroid of the web subcontour, while the moment Mz,Ed has to be divided into two components of Mz,Ed,f = Mz,Ed/2 to be applied at the centroids of the flange subcontours. Flexural rotations and warping are allowed for both supports.

3.3 Options Used for Modelling Imperfections

Steel rolled structural elements are imperfect. Regarding their stability, the most important factors are an initial bow of the element and material anisotropy resulting from technological self-equilibrated residual stresses (remaining after heating and cooling during the thermal rolling processes). There are generally two approaches used for the inclusion of imperfections in modelling of the behaviour of real structural elements:

-

Approach 1 with individual modelling of both types of imperfections that have physical meaning.

-

Approach 2 with an equivalent bow imperfection to reproduce the stability behaviour modelled with inclusion of both types of imperfections.

In the former approach, the bow imperfections are typically related to the tolerances on the straightness of the structural I- and H-sections and standard residual stress patterns. The values of the manufacturing bow tolerances e0y given in the execution code (EN 10034 EN 10034 1996) may be used: these magnitudes are (3/2000) L for HEB 300 and (1/1000) L for IPE 500 (where L is a length of the element). In addition to the application of geometric imperfections at the fabrication tolerance level, material imperfections need to be considered. The standard patterns of the residual stresses are shown in Fig. 4 (Boissonnade and Somja 2012). For elements of different steel grades, the residual stress pick usually refers to grade S 235 so that fy,red = 235 N/mm2 is adopted instead of fy for this particular grade of steel rolled products.

The latter approach is associated with the so-called General Method of buckling assessment in Part 1-1 of Eurocode 3 (EN 1993-1-1 2005). The equivalent bow imperfections may be referred to as the eigenmodes obtained from the solution of LBA. Utilizing the analytical solution of the beam buckling strength under uniform moment, the amplitude e0,LT of the equivalent lateral crookedness may be evaluated following (Rykaluk 2012; Giżejowski et al. 2016a; Papp 2016). It is expressed hereafter as a function of the LTB curve imperfection factor as follows:

where Bc,Rk is the bimoment section resistance and the other symbols are explained above and in the ECCS design manual (da Silva et al. 2010b).

The amplitude calculated according to Eq. (5) depends upon the section classification. Figure 5 presents the amplitudes e0,LT of the equivalent geometric imperfections calculated for the plastic section properties (solid lines marked by Equ-plastic) and elastic section properties (dashed lines marked by Equ-elastic) for the two considered I-sections (see Fig. 5a for HEB 300 and Fig. 5b for IPE 500).

It is noticeable that the amplitude of the equivalent geometric imperfection profile of the HEB 300 section is much greater than that of the IPE 500 section. This trend is opposite to that of the imperfection factor values αLT for the buckling curves related to IPE 500 (greater for IPE 500 than for HEB 300, as given in Table 2). Furthermore, one can note that the out-of-plane equivalent imperfection amplitudes are much greater than the acceptable tolerance limit utilized in Approach 1, the values of which are presented in Fig. 5 as dotted lines.

3.4 Solution Options Used in the Numerical Analysis

In the stability analysis adopted in this paper with a nonlinear geometry and nonlinear relationship between stress and strain, the full coupling between the prebuckling and postbuckling deformation states is considered. ABAQUS is used, in which the theory of large displacement is implemented and available through the option Nlgeom (ABAQUS Theory manual 2011; ABAQUS/Standard User’s manual 2011). In the applied theory, the formal structure of the incremental equations of elasto-plasticity is similar to the classical theory of small displacements, but with a different interpretation of the tensor representations (de Souza Neto et al. 2008; Khan and Huang 1995). In large displacement theory, the material derivatives of the Cauchy stress tensor and of the small deformation strain tensor have to be replaced with objective derivatives of the Kirchhoff stress tensor and logarithmic strain tensor (the logarithm of the left Cauchy–Green stretch tensor) (Bonet and Wood 2008). Consequently, in the case of uniaxial testing with the assumption of material isotropy and by taking into account the incompressibility of the plastic deformation, the following conversion of experimental engineering stress–strain data is needed (which is necessary due to the application of the theory of plasticity for large deformations) (ABAQUS/Standard User’s manual 2011; Giżejowski et al. 2017b):

where εn and σn are of engineering values, the latter treated as a component of a nominal stress tensor (first Piola–Kirchhoff stress tensor), and \(\sigma\) is a component of Cauchy’s true stress tensor assuming incompressibility of the material.

The elastic–plastic tangent stiffness matrix and the residual load vector of the behaviour of the structural model are integrated numerically using the Riks–Crisfield implicit algorithm (Riks 1979; Crisfield 1981). The application of the Riks–Crisfield algorithm provides stability under nonzero stress boundary conditions, as in the analysed problem, and allows a critical point crossing on the global equilibrium path.

The adopted solution procedure is applied for verification of the dimensionless buckling resistance curves of mono-symmetric bending about the y–y axis calculated with different values of the amplitude of equivalent geometric imperfections. In Giżejowski et al. (2017a), it has been concluded that Eurocode’s LTB curves coincide with the resistance curves obtained from the general interaction equations for biaxial bending and compression when NEd = Mz,Ed = 0. Furthermore, it was indicated that there were substantial differences in the resistance curves derived from the so-called General case [according to 6.3.2.2 (EN 1993-1-1 2005)] and Special case [according to 6.3.2.3 (EN 1993-1-1 2005)] referring to rolled I-sections and equivalent welded I-sections. The amplitudes applied are based on the section plastic resistance properties (marked as “plast” in Fig. 6) and on the section elastic resistance properties (marked as “elast” in Fig. 6). Nine discrete values of the slenderness ratio \(\overline{\lambda }_{z}\) are selected (see Tables 3 and 4).

The results obtained from the FEM simulations calculated according to Eq. (5) are compared in Fig. 6 for ψy= 1, 0 and − 1 with the results from Eurocode’s General case (buckling curves χLT marked by Gc—red solid line) and Eurocode’s Special case (curves χLT,mod marked by Sc—blue solid line) as presented in Gizejowski and Stachura (2017). Furthermore, the results from the proposal presented in Taras and Greiner (2010) and Greiner and Taras (2010) for updating the Eurocode’s lateral-buckling curves (denoted by the dashed line and labelled “Greiner and Taras”) and from the authors’ proposal developed hereafter (denoted by the dotted line and labelled “Proposal”) are also included.

The moment gradient buckling assessment case can be conveniently evaluated using the critical moment equation derived on the basis of the superposition of symmetric and anti-symmetric moment diagrams (Giżejowski et al. 2016b) and the modification presented in Giżejowski et al. (2016a, c) for the inclusion of the effect of prebuckling displacements. This assessment leads to a lateral-torsional buckling reduction factor χLT,mod in a form similar to that of clause 6.3.2.2 of EN 1993-1-1 (2005) but dependent upon the moment gradient ratio and the section moments of the inertia ratio:

in which β is an approximation of the critical moment modification factor according to Giżejowski et al. (2016b) for the cases of moment gradient:

The imperfection factor of Gc is modified with regard to the moment modification factor as follows:

the LT buckling slenderness ratio is modified with regard to the effect of the prebuckling displacements (Giżejowski et al. 2016a, c):

and the plateau slenderness ratio modified with regard to the effect of the prebuckling displacements and the moment modification factor is

where the section moments of inertia ratio is

The results presented in Fig. 6 show that for class 1 and 2 sections, it is rational to use the equivalent imperfection profile calculated for e0,LT based on the section plastic properties. The buckling resistance evaluated on the basis of the plastic section resistance is a lower value than that for the elastic section resistance. Therefore, this is hereafter taken into consideration.

The lateral-torsional buckling resistances χLT,mod according to the Sc approach of clause 6.3.2.3 of EN 1993-1-1 (2005), the author’s proposal and the Greiner and Taras (2010) approach allow for the evaluation of higher values in comparison to those of the Gc approach [according to clause 6.3.2.2 of EN 1993-1-1 (2005)]. They are closer to the results from the finite element simulations. For the considered HEB section in the case of SMY, the case of TMY for reference slenderness \(\overline{\lambda }_{LT,ref}\) greater than 1.3 and the case of AMY for \(\overline{\lambda }_{LT,ref}\) > 1.5, the results from the authors’ proposal are closer to the numerical results than the results of the Greiner and Taras (2010) approach. For the considered IPE section and in the cases of SMY and AMY, the results from the authors’ approach and Greiner and Taras (2010) approach are similar. Only in the case of TMY for the considered IPE section, the buckling curve from Greiner and Taras (2010) for \(\overline{\lambda }_{LT,ref}\) > 0.5 is slightly closer to numerical results than those of the authors’ proposal.

It is therefore rational to recommend the authors’ approach or Greiner and Taras (2010) proposal as an alternative approach to that of the current Eurocode 3 for rolled and equivalent welded I- and H-sections (Sc) for the design of rolled I-section beams. Note that both proposals are more general than that of Eurocode 3 since they account for more parameters; therefore, these approaches are not restricted to the section dimensions of the rolled I-sections. However, one must remember that the beam section must not be susceptible to either local or distortional buckling.

3.5 Imperfection Modelling Techniques and Loading History Adopted

First, the equivalence of two approaches, namely, Approaches 1 and 2 as explained in Sect. 3.3, to imperfection modelling is discussed with regard to the evaluation of buckling resistance in mono-axial bending about the section y–y axis. To verify the adequacy of the equivalent imperfection model for biaxial bending, the results of this modelling technique are compared with those based on separate geometric and material imperfection models for mono-axial bending. Detailed results are presented elsewhere, and only a brief summary is presented here. Figure 7 reproduces the finite element results presented in Giżejowski et al. (2017a) for the S 355 steel grade and referring to a uniform moment; the discrete diamond points are from the finite element simulation based on Approach 1 for imperfection modelling, and the triangular points indicated by GM-EC 3 are based on Eurocode’s so-called General Method with equivalent geometric imperfection modelling (Approach 2 according to Sect. 3.3). Both imperfection modelling techniques are used for the buckling resistance assessment of two types of I-sections. The pick values of the residual stresses refer to the yield stress of the common steel grade, i.e., fy,ref = 235 N/mm2. One can conclude that both approaches lead to practically the same results with regard to the accuracy required in engineering practice. Approach 2 is simpler and is preferred in research directed towards practical applications. Therefore, the technique of equivalent geometric imperfections is used hereafter for the evaluation of the buckling resistance curves in biaxial bending.

As to the loading history, the initial configuration of imperfect beams is identified first with regard to either Approach 1 or 2 prior to the load applications. Three basic loading paths for an evaluation of the loading history on the LTB resistance may be selected, and the interaction curves corresponding to these three histories are compared below.

-

Path A First application of support moments with the considered moment gradient ratio ψz to produce the required Mz,Ed(x) moment diagram; then, the application of the support moments with moment gradient ratio ψy to produce the required My,Ed(x) moment diagram. The Riks incrementation method of the ψy parameter is then applied until the buckling resistance under biaxial bending is attained.

-

Path B The load sequence application opposite to that of Path A by substituting subscripts “y” for “z”, and vice versa. In this case, care has to take with regard to modelling the flange moment responses of the I-sections since this response is a combination of minor axis bending and warping torsion.

-

Path C The simultaneous application of support moments with the moment gradient ratios ψy and ψz for the loading cases identified in Table 1, with a predefined proportionality ratio ψ = ψy/ψz (or ψ = ψz/ψy) subjected to incrementation. The Riks incrementation method of the ψ parameter is then applied until the buckling resistance under biaxial bending is attained.

Comparing the results from three possible loading paths allows the prediction of the lower bound formulation for the resistance assessment of the structural beam element that may be subjected to any histories with load effects varying independently under different combinations of action on the structure. The results presented in Fig. 8 are for the load case SMY–SMZ and all three loading histories considered. Two approaches for the imperfection modelling were used, namely, Approach 1—the independent modelling of material and geometric imperfections—and Approach 2—the combined modelling of material and geometric imperfections in the form of an equivalent geometric imperfection profile.

Comparison of results from the buckling resistance simulations for the load case SMY–SMZ (ψy = ψz = 1) and for the load sequences according to paths A, B and C for different values of the slenderness ratio \(\overline{\lambda }_{z}\): a effect of using different paths and b effect of different imperfection modelling approaches

Figure 8a shows the effect of the path case on the biaxial bending resistance interaction curves. The results show that out of the three possibilities of defining the ultimate beam state under the combination of in-plane and out-of-plane moments, there is a negligible effect of the loading path on the resistance interaction curves from the engineering application point of view. The differences are not greater than 1%, and it may be summarized that Path A gives the lower bound assessment of the buckling resistance, while Path B provides that of the upper bound. This result is easily explainable since the application of minor axis moments in the first stage of analysis may be treated as a superimposition of two initial states, one produced by imperfections and the second by minor axis bending.

Figure 8b presents the verification of the lower bound resistance estimation in the case of biaxial bending and the equivalent geometric imperfections approach as well as the resistance based on the explicit introduction of residual stresses and geometric imperfections at the manufacturing tolerance level in finite element simulations. By observing the results, one can come to the conclusion that both approaches of imperfection modelling provide results of a similar accuracy as that observed for mono-axial bending for lesser values of mcz (cf. Fig. 7), while the differences continuously decrease with increase in mcz values.

In conclusion, it is justifiable to use the loading history according to Path A and the imperfection modelling technique based on Approach 2 of the equivalent geometric imperfection profile. The profile was considered the lowest SMY buckling mode with a “plastic” amplitude according to Fig. 5.

3.6 Mesh Refinements

For the SM finite element simulations, refinements of the discretization scheme are checked to select the scheme that ensures that the accuracy is acceptable from an engineering point of view. The exercise is similar to that carried out for compression and mono-axial bending without lateral-torsional buckling, and the results are presented in Giżejowski et al. (2016d).

To evaluate the influence of the mesh refinements in the SM simulations on the equilibrium path evaluation and the ultimate strength prediction, the initial coarse discretization scheme is refined to obtain denser meshes. The considered meshes, M-1 to M-6, are shown in Table 5.

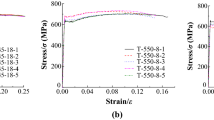

Simulations were performed for all the considered FEM meshes for different mcz values. The mcz values were applied first, and then the values of mcy were changed incrementally by using the Riks algorithm to reach the limit point on the equilibrium path. Very consistent results were obtained for different slenderness ratio values, and representative examples are given in Figs. 9 and 10 for the slenderness ratio of 0.5. Figure 9 includes the results for mcz equal to zero and 0.25, and Fig. 10 includes the results for mcz equal to 0.5 and 0.9. The horizontal coordinates URy denote the twist rotation.

The obtained results confirm the conclusion made in Giżejowski et al. (2016d), that a sufficient accuracy is obtained with the use of the M-3 mesh. This mesh is therefore used in all the FEM simulations presented hereafter.

4 Verification of Eurocode’s Resistance Strength Curves for Beams Under Biaxial Bending

In this section, in the Eurocode prediction of biaxial bending resistance, the values of χLT,mod according to the Sc approach for rolled I-sections [according to clause 6.3.2.3 of EN 1993-1-1 (2005)] are used in the interaction equations of clause 6.3.3, in which NEd = 0 is assumed. Furthermore, Eurocode’s Method 1 is considered for the comparison of beam resistances under biaxial bending with those from the FEM simulations, and comments regarding the use of only Method 2 are included hereafter to provide more a brief discussion.

The finite element models were previously validated; for many cases, these validations were presented in Giżejowski et al. (2016c, d, 2017a, b) and Gizejowski and Stachura (2017). This paper is a continuation of long-term research and is part of the current research of Papp (2016). It must be stated that validation of the finite element results is performed only through a comparison with the results obtained by using the Eurocode 3 analytical formulation (EN 1993-1-1 2005) that was validated prior to its codification. These results, in most cases, are far more conservative than the FEM results, but all significant discrepancies between the FEM modelling and Eurocode 3 predictions are carefully analysed before formulating any conclusions. The conclusions presented in this paper are not an extrapolation of the results but are stated on the basis of solid and checked analysis. To present a wider view of the analysed topic in terms of full-scale experimental tests, the following classical papers may be addressed (Anslijn 1983; Kloppel and Winkelmann 1962; Chubkin 1959; Birnstiel et al. 1967).

4.1 Finite Element Simulations for Buckling Resistance for the Bending Moment Diagram of Case SMY

Figure 11 shows the comparison of the finite element simulations and the analytical formulations of Eurocode’s Method 1 (EN 1993-1-1 2005) for two considered rolled sections and cases SMY–SMZ, SMY–TMZ and SMY–AMZ. The beam of the HEB 300 section is subjected to larger in-plane displacements than its counterpart of the IPE 500 section. The large in-plane displacements are accounted for in the analysis option considered for the finite element simulations in ABAQUS. The Eurocode 3 Sc approach to the evaluation of LT buckling leads to slightly higher resistance predictions of the narrow flange I-sections if compared with the FEM simulation results; in contrast, the predictions are opposite for wide flange sections (cf. Fig. 6a). This is also clearly visible in the comparison of the biaxial strength predictions shown in Fig. 13.

It is shown in Fig. 11a that the finite element interaction curves (represented by solid lines) for the medium slenderness ratio \(\overline{\lambda }_{z}\) of the HEB 300 section exhibit two distinctive parts, namely, a concave branch (for the low values of mcz) and a convex branch (for higher values of mcz). Eurocode’s recommendations of not considering the large twist rotations lead to interaction curves (represented by dashed lines), constituting a safe estimation of the beam biaxial bending ultimate state. The interaction curves for the IPE section that is less sensitive to the effect of prebuckling displacements on the critical state are presented in Fig. 11b. Since the buckling state under mono-axial bending about the y–y axis is reached in this section before the large in-plane displacements could have occurred, the reduction of the buckling resistance in biaxial bending is faster than observed for the wide flange beams.

When the minor axis bending moment diagram becomes more asymmetric, the concave part of the FEM resistance curves gradually vanishes, and the curve becomes fully convex for the whole range of the slenderness ratio \(\overline{\lambda }_{z}\), regardless the web-to-flange dimension proportion. The predictions made using Method 1 show an opposite trend. For uniform minor axis bending, the Eurocode 3 strength curves consist of two parts, the lower mcz values of these curves become approximately linear as purposefully adopted for Method 2 in EN 1993-1-1 (2005). For a greater minor axis moment gradient ratio, the predictions made with the use of Eurocode 3 Method 1 create a more concave strength curve instead of a more convex curve, as predicted by the FEM simulations. It might be shown that the Eurocode 3 Method 2 linear branch (instead of the concave branch of Eurocode 3 Method 1) gives, in this case, less conservative predictions than those from the FEM simulations.

4.2 Finite Element Simulations for Buckling Resistance for the Bending Moment Diagram of Case TMY

Figure 12 shows the comparison of the finite element simulations and the analytical formulations of Eurocode’s Method 1 (EN 1993-1-1 2005) for two considered rolled sections for which the major axis moment Myd is applied over the left support. This situation is denoted hereafter as TMY*. The two-star superscript denotes a reversal of the situation when the moment in either plane is applied over the right support. The cases considered are TMY*–SMZ, TMY*–TMZ*, TMY*–TMZ** and TMY*–AMZ. Two different cases of minor axis bending are therefore distinguished, namely, TMY*–TMZ* corresponding to the moment Mzd applied over the left support, and TMY*–TMZ** corresponding to the moment Mzd applied over the right support.

Comparing the results, it has to be noted that Eurocode’s interaction curves in Fig. 12b and c are the same for the same section in the TMY*–TMZ* and TMY*–TMZ** cases, respectively. The finite element results are substantially different in both cases. One can conclude that the concept of equivalent uniform moment used in the code does not allow for a proper resistance assessment in the case TMY*–TMZ** since it underestimates the resistance by an unacceptable level, e.g., for the HEB section and the slenderness ratio \(\overline{\lambda }_{z}\) = 2.0, interaction between moments applied about both principal axes occurs for values of mcy ≥ 0.8. Below this limit, the ultimate limit state is reached when either the minor axis moment attains the corresponding section resistance or the major axis moment attains its corresponding section resistance. Contrarily, Eurocode’s interaction curve requires the interaction in the range of approximately mcy ≥ 0.35 for the same slenderness. Comparing the results presented in Fig. 12a, b, d, one can observe the similarity of the shape of the FEM interaction curves and its lesser sensitivity to the change towards a more convex shape when the minor axis moment gradient ratio increases. Accordingly, Eurocode’s Method 1 interaction curves and the FEM resistance curves are more similar in the TMY* cases than in the SMY cases; this is especially observed for TMY*–AMZ in comparison to SMY–AMZ.

4.3 Finite Element Simulations for Buckling Resistance for the Bending Moment Diagram of Case AMY

Figure 13 shows the comparison of the finite element simulations and the analytical formulations of Eurocode’s Method 1 (EN 1993-1-1 2005) for the two considered rolled sections and cases AMY–SMZ, AMY–TMZ and AMY–AMZ. The H 300 I-section beams exhibit substantially greater resistance in biaxial bending than their IPE 500 counterparts. For the slenderness ratios considered and for low mcz values, the full plastic moment resistance My,pl,Rd may be reached by the moment My,Ed, regardless of the values of the minor axis moment gradient ratios. The IPE 500 beams remain more sensitive to LT buckling in this range.

5 General Conclusions and Final Remarks

The buckling phenomenon of perfect I-section beams under compression and under two-directional bending about the principal axes y–y and z–z, laterally and torsionally unrestrained between supports, is studied in this paper. Furthermore, sections of bending class 1 or 2 are taken into consideration, implying that local instability does not affect the stability behaviour of the considered beams. The overall buckling problem is therefore converted to a spatial second-order bending and warping torsion problem under a general moment gradient loading, and the limit points on the inelastic equilibrium path of the imperfect elements are evaluated. The conventional simple boundary conditions with loading cases producing different moment gradient conditions along both principal axes are considered. The principal objective of the paper is to perform numerical simulations for all the considered loading cases and verify the Eurocode 3 interaction equation approach used for the buckling resistance evaluation in the case of biaxial bending when the stability load effect My,Ed produced by the applied moments My,d is associated with the non-stability load effect Mz,Ed produced by the applied moments Mz,d. Since the considered calculations refer to imperfect members, they allow for a better understanding of the behaviour of real class 1 or 2 section beams and a better prediction of the accuracy of the resistance criteria obtained from the simplification of Eurocode’s recommendations related to biaxial bending and compression.

Current stability criteria rely on uncoupling the beam stability resistance and the cross-section resistance, resulting in a nonuniform safety assessment of I-section beams, especially when subjected to a negative moment gradient ratio, i.e., when the moments in both planes are acting over the opposite beam supports. Since the safety assessment of beam buckling resistance evaluation in biaxial bending has not yet been widely investigated, this paper focuses on advanced analysis and GMNIA-based numerical simulations. The finite element simulations for different moment gradient situations are presented for the verification of Eurocode’s analytical approach to the buckling resistance of beams. Cases of mono-axial bending about the section major axis and biaxial bending, including the moment gradient effect for bending about both section principal axes, are evaluated.

The developed finite element model of the equivalent geometric imperfections, applied to biaxial bending, allows for the identification of the moment gradient parameters ψy and ψz for which the current design recommendations lead to quite conservative predictions of the buckling resistance. Specifically, the finite element results are substantially different in cases TMY*–TMZ* and TMY*–TMZ**, while Eurocode’s interaction curves for both cases are the same. One can conclude that such differences might be mainly attributed to the concept of equivalent uniform moment, which replaces the real moment gradient cases. An improved accuracy between the results of the finite element simulations is expected when a new formulation would be proposed that abandons the concept of equivalent uniform moment factors. This aspect will be a subject of the authors’ forthcoming research activities dealing with the resistance evaluation of imperfect beams for out-of-plane behaviour.

In Sect. 4, the comparison of the analytical results obtained from Method 1 of Eurocode 3 and the finite element method simulation results is presented. The analytical solutions were obtained for the considered rolled cross-sections, and the moment distributions are denoted as SMY–SMZ, SMY–TMZ and SMY–AMZ and are plotted against the FEM solutions with shell modelling. The detailed conclusions on these comparisons are provided underneath the relevant graphs; however, it is worth noting that in all cases, Eurocode’s expectations are conservative. As it has already been mentioned, in some cases, the differences are of a magnitude of several percent. However, the differences are sometimes greater; for example, in the case of TMY–TMZ for both HEB 300 and IPE 500, the differences are substantial. Comparing the graphs in Fig. 12, it is possible to conclude that, for some initial moment distributions, the nonlinearity of the problem is clearly manifested. This nonlinearity cannot be taken into account with the beam theory (Bernoulli’s theory or the thin-walled theory) but requires full spatial modelling and proper constitutive modelling. The shell finite element models formulated by considering large deformation theory with elasto-plasticity constitutive relationships like those presented here may be treated as the first reliable step in the movement towards proper stability problem modelling. The limitations resulting from the shell geometry description are not as conservative as those from beam theory, and the number of elements in the model are reasonable compared with, for example, 3D modelling (Giżejowski et al. 2016c).

References

ABAQUS Theory manual, Version 6.11, Dassault Systèmes (2011).

ABAQUS/Standard User’s manual, Version 6.11, Dassault Systèmes (2011).

Anslijn, R. (1983). Tests on steel I-beam-columns subjected to thrust and biaxial bending. CRIF report MT157, Center De Recherches Scientifiques Et Techiques De L’industrie De, Fabrications Metalliques Brussels, Belgium.

Aydın, R., & Doğan, M. (2007). Elastic, full plastic and lateral torsional buckling analysis of steel single-angle section beams subjected to biaxial bending. Journal of Constructional Steel Research, 63(1), 13–23.

Baptista, A. M. (2012a). Resistance of steel I-sections under axial force and biaxial bending. Journal of Constructional Steel Research, 72, 1–11.

Baptista, A. M. (2012b). Analytical evaluation of the elastic and plastic resistances of double symmetric rectangular hollow sections under axial force and biaxial bending. International Journal of Non-Linear Mechanics, 47(9), 1033–1044.

Belingardi, G., & Peroni, L. (2005). Numerical investigation on plastic collapse of thin walled beams subjected to biaxial bending. In Proceedings of VIII international conference on computational plasticity, COMPLAS VIII, Barcelona (pp. 1–4).

Belingardi, G., & Peroni, L. (2007). Experimental investigation of plastic collapse of aluminium extrusions in biaxial bending. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences, 49(5), 554–566.

Birnstiel, C., Leu, K. C., Tesoro, J. A., & Tomasetti, R. L. (1967). Experiments on H-columns under biaxial bending. New York: New York University.

Boissonnade, N., Hayeck, M., Saloumi, E., & Nseir, J. (2017). An overall interaction concept for an alternative approach to steel members design. Journal of Constructional Steel Research, 135, 199–212.

Boissonnade, A., Jaspart, J.-P., Muzeau, J.-P., & Villette, M. (2004). New interaction formulae for beam-columns in Eurocode 3: The French–Belgian approach. Journal of Constructional Steel Research, 60, 421–431.

Boissonnade, N., & Somja, H. (2012). Influence of imperfections in FEM modeling of lateral torsional buckling. In Proceedings of annual stability conference: structural stability research council, Grapevine (pp. 1–15).

Bonet, J., & Wood, R. D. (2008). Nonlinear continuum mechanics for finite element analysis (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bradford, M. A. (1995). Evaluation of design rules of the biaxial bending of beam-columns. Civil Engineering Transactions, Institution of Engineers, Australia, 37(3), 241–245.

Chubkin, G. M. (1959 ). Experimental research on the stability of thin plate steel members with biaxial eccentricity. Paper No. 6 in the book Analysis of spatial structures, Vol. 5, Moscow (G.I.L.S.).

Crisfield, M. A. (1981). A fast incremental/iterative solution procedure that handles “snap-through”. Computers & Structures, 13, 55–62.

da Silva, L. S., Marques, L., & Rebelo, C. (2010a). Numerical validation of the general method in EC3-1-1 for prismatic members. Journal of Constructional Steel Research, 66, 575–590.

da Silva, L. S., Simoes, R., & Gervasio, H. (2010b). Design of steel structures, Eurocode 3: Design of steel structures, Part 1-1: General rules and rules for buildings, ECCS Eurocode design manual. Berlin: Ernst & Sohn.

de Souza Neto, E. A., Peric, D., & Owen, D. R. J. (2008). Computational methods for plasticity: Theory and applications. New York: Wiley.

EN 10034 EN 10034. (1996). Structural steel I and H sections-tolerances on shape and dimensions. Brussels: CEN.

EN 1993-1-1. (2005). Eurocode 3: Design of steel structures. Part 1-1. General rules and rules for buildings. Brussels: CEN.

Gizejowski, M., & Stachura, Z. (2017). On LTB resistance assessment of prismatic I-section beams according to Eurocode 3. Journal of Civil Engineering, Environment and Architecture, 34(64-3/I/17), 427–436.

Giżejowski, M. A., Stachura, Z., Szczerba, R. B., & Gajewski, M. D. (2016a). Numerical study of buckling resistance of steel I-section members under two directional bending. In Proceedings of 6th international conference on structural engineering, mechanics and computation (pp. 267–268) (e-book on CD: 758–763).

Giżejowski, M. A., Stachura, Z., & Uziak, J. (2016b). Elastic flexural-torsional buckling of beams and beam-columns as a basis for stability design of members with discrete rigid restraints. In Proceedings of 6th international conference on structural engineering, mechanics and computation (pp. 261–262) (e-book on CD: 738–744).

Giżejowski, M. A., Szczerba, R. B., & Gajewski, M. D. (2017a). LTB resistance of rolled I-section beams. FEM verification of Eurocode’s buckling curve formulation. In Proceedings of Eurosteel 2017 in: Online collection for conference papers in civil engineering (Vol. 1, No. 2–3, pp. 1325–1334). Berlin: Ernst & Sohn Verlag für Architektur und technische Wissenschaften GmbH & Co. KG.

Giżejowski, M. A., Szczerba, R., Gajewski, M. D., & Stachura, Z. (2016c). On the resistance evaluation of lateral-torsional buckling of bisymmetrical I-section beams using finite element simulations. Procedia Engineering, Open Access Journal, 153, 180–188.

Giżejowski, M. A., Szczerba, R., Gajewski, M. D., & Stachura, Z. (2016d). Beam-column in-plane resistance based on the concept of equivalent geometric imperfections. Archives of Civil Engineering, 62/II(4), 35–71.

Giżejowski, M. A., Szczerba, R., Gajewski, M. D., & Stachura, Z. (2017b). Buckling resistance assessment of steel I-section beam-columns not susceptible to LT-buckling. Archives of Civil and Mechanical Engineering, 17(2), 205–221.

Greiner, R., & Lindner, J. (2006). Interaction formulae for members subjected to bending and axial compression in Eurocode 3: The method 2 approach. Journal of Constructional Steel Research, 62, 757–770.

Greiner, R., & Taras, A. (2010). New design curves for LT and TF buckling with consistent derivation and code-conform formulation. Steel Construction, 3(3), 176–186.

Kala, Z. (2015). Sensitivity and reliability analyses of lateral-torsional buckling resistance of steel beams. Archives of Civil and Mechanical Engineering, 15, 1098–1107.

Kala, Z., & Valeš, J. (2017). Global sensitivity analysis of lateral-torsional buckling resistance based on finite element simulations. Engineering Structures, 134, 37–47.

Khan, A. S., & Huang, S. (1995). Continuum theory of plasticity. New York: Wiley.

Kim, H.-S., & Wierzbicki, T. (2000). Numerical and analytical study on deep biaxial bending collapse of thin-walled beams. International Journal of Mechanical Sciences, 42(10), 1947–1970.

Kloppel, K., & Winkelmann, E. (1962). Experimental and theoretical investigations on the ultimate strength of biaxially compressed steel columns. Der Stahlbau, 31(2), 33.

Osterrieder, P., & Kretzschmar, J. (2006). First-hinge analysis for lateral buckling design of open thin-walled steel members. Journal of Constructional Steel Research, 62(1–2), 35–43.

Papp, F. (2016). Buckling assessment of steel members through overall imperfection method. Engineering Structures, 106, 124–136.

Riks, E. (1979). An incremental approach to the solution of snapping and buckling problems. International Journal of Solids and Structures, 15, 529–551.

Rodriguez-Gutierrez, J. A., & Aristizabal-Ochoa, J. D. (2017). Bending moment-axial force-curvature interactions for metal beam-column sections. Structures, 10, 139–146.

Rykaluk, K. (2012). Stability problems of metal structures. Wrocław: Dolnośląskie Wydawnictwo Edukacyjne. (in Polish).

Taras, A., & Greiner, R. (2010). New design curves for lateral-torsional: Proposal based on a consistent derivation. Journal of Constructional Steel Research, 66(5), 648–663.

Trahair, N. S. (1993). Flexural-torsional buckling of structures. London: CRC Press.

Trahair, N. S., Bradford, M. A., Nethercot, D. A., & Gardner, L. (2008). The behaviour and design of steel structures to EC3 (4th ed.). London: Taylor & Francis.

Vayas, I., Charalampakis, A., & Koumousis, V. (2009). Inelastic resistance of angle sections subjected to biaxial bending and normal forces. Steel Construction, 2, 138–146.

Weiss, S., & Giżejowski, M. A. (1991). Stability of metal structures. Rod structures. Warsaw: Arkady. (in Polish).

Yang, B., Kang, S.-B., Xiong, G., Nie, S., Hu, Y., Wang, S., et al. (2017). Experimental and numerical study on lateral-torsional buckling of singly symmetric Q460GJ steel I-shaped beams. Thin-Walled Structures, 113, 205–216.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Giżejowski, M., Szczerba, R., Gajewski, M. et al. Buckling Resistance Criteria of Prismatic Beams Under Biaxial Moment Gradient. Int J Steel Struct 19, 559–576 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13296-018-0143-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13296-018-0143-6