Abstract

Diabetes mellitus is associated with the development of neuronal tissue damage in different central and peripheral nervous system regions. A common complication of diabetes is painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy. We have explored the antihyperalgesic and neuroprotective properties of Rosmarinus officinalis L. extract (RE) in a rat model of streptozotocin (STZ)-induced diabetes. The nociceptive threshold and motor coordination of these diabetic rats was assessed using the tail-flick and rotarod treadmill tests, respectively. Activated caspase-3 and the Bax:Bcl-2 ratio, both biochemical indicators of apoptosis, were assessed in the dorsal half of the lumbar spinal cord tissue by western blotting. Treatment of the diabetic rats with RE improved hyperglycemia, hyperalgesia and motor deficit, suppressed caspase-3 activation and reduced the Bax:Bcl-2 ratio, suggesting that the RE has antihyperalgesic and neuroprotective effects in this rat model of STZ-induced diabetes. Cellular mechanisms underlying the observed effects may, at least partially, be related to the inhibition of neuronal apoptosis.

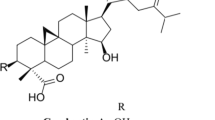

Graphical Abstract

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Diabetes mellitus is a well-known metabolic disorder associated with hyperglycemia and other metabolic complications that result from disturbances in insulin secretion or insulin action [1]. A growing body of scientific research shows an association between metabolic disorders and a number of neurodegenerative diseases. Epidemiologic research has revealed that patients with diabetes are at a significantly increased risk of developing neural tissue damage and that diabetes causes profound changes in the peripheral and central nervous systems [1, 2]. A number of population-based studies have reported that more than one-half of all diabetic patients exhibit diabetic neuropathy and pain related to diabetes neuropathy [1, 3, 4].

It is well established that hyperglycemia is one of the main underlying factors of injury to the nervous system in diabetic patients [5, 6]. Some study results have led to the proposal that diabetic neuropathy is related to the constant generation of reactive oxygen species through glucose auto-oxidation and the subsequent development of advanced glycation end-products, activation of nuclear enzyme poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase and reduced antioxidant protection [2, 4]. In addition, apoptosis has been suggested as a possible mechanism for the high glucose-induced neural dysfunction and cell death observed in many investigations [7].

There is an overall growing demand for herbal medicines, both in developing and developed countries. In this context, the antinociceptive and neuroprotective properties observed in many natural products has drawn intensive research interest [8]. Furthermore, several in vivo and in vitro investigations have shown the beneficial effects of herbal medicines on neurodegenerative disorders, such as diabetic neuropathy, Parkinson disease and Alzheimer disease [9,10,11].

Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.; family Lamiaceae) is a perennial herb that is typically found in the Mediterranean region. It is known as a medicinal herb due to its high antioxidant activity and its use in traditional medicine for the treatment of diabetes mellitus [12,13,14]. In addition, several studies have been shown that rosemary extract has antinociceptive, anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic and neuroprotective properties [15,16,17,18,19]. However, to date there has been no report on the antinociceptive and neuroprotective effects of rosemary in an in vivo model of diabetic neuropathic pain. The study reported here was therefore designed to investigate the possible effects of R. officinalis leaf extract (RE) in a rat model of diabetic neuropathic pain by evaluating its possible effect on hyperglycemia-induced neuronal apoptosis.

Materials and methods

Materials

Streptozotocin (STZ) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA). Primary monoclonal anti-β-actin and primary polyclonal anti-caspase 3 antibodies were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology Inc. (Danvers, MA, USA). Primary monoclonal anti-Bcl-2 and primary polyclonal anti-Bax antibodies were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Dallas, TX, USA).

Preparation of the RE

Rosemary leaf extract was prepared in the Razi Herbal Medicines Research Center (Lorestan, Iran). Herbal identification was confirmed by the Botany Department of Lorestan University. Healthy leaves were dried under shaded conditions to avoid the decomposition of chemical constituents, and then about 200 g of the dried rosemary leaves were ground into fine powder and the powder extracted with ethanol/water (70:30). The extract was subsequently filtered under reduced pressure in a rotary evaporator and the filtrate concentrated to dryness. The resulting RE (about 10 g) was freeze-dried. For the in vivo study, portions of the crude RE were weighed and dissolved in physiological saline. High-performance liquid chromatography analysis showed that the RE contained about 4.5% rosmarinic acid (as the main polyphenol component of RE).

Animals and experimental groups

Forty eight male Wistar rats (body weight 220–250 g) were purchased from the Pasteur Institute of Tehran and housed four per cage under a 12/12-h light/dark cycle in a temperature-controlled room (22 ± 1 °C). The animals were given 1 week to adapt to the new environment (Razi Herbal Medicines Research Center animal housing unit). Food and water were available ad libitum. Animals were handled daily (9.00–11.00 a.m.) 5 days before the experiment in order acclimate them to the experimental conditions and minimize nonspecific stress responses. The 48 rats were randomly placed into six experimental groups of 6–8 animals each (see Table 1). All experimental protocols were performed according to the ethical guidelines of Lorestan University of Medical Sciences based on the U.S. NIH Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (https://grants.nih.gov/grants/olaw/guide-for-the-care-and-use-of-laboratory-animals.pdf).

Experimental protocols

Diabetes was induced by a single intraperitoneal injection of STZ (55 mg/kg body weight) that had been freshly dissolved in 0.1 mol/l citrate buffer. The control group comprised rats receiving an injection of citrate buffer. Diabetes was confirmed in the STZ-injected rats 1 week after the injection by measuring serum glucose concentrations. Glucose concentration was assayed enzymatically using a glucose oxidase–peroxidase (GOD–POD) kit (Pars Azmon Co., Qom, Iran). Those rats with blood glucose levels of ≥ 250 mg/dl were considered to have diabetes. Once the development of diabetes had been confirmed, the diabetic rats were immediately (1 week after STZ injection) given the RE (100, 150, or 200 mg/kg) or saline (as RE vehicle; Diabetes + saline group) once daily through oral gavage for 21 days (3 weeks). Four weeks after the STZ injection, the rats were killed by decapitation under CO2 anesthesia.

Nociception assessment

The nociceptive threshold was evaluated using the tail-flick test [13]. The intensity of the beam was adjusted to cause a mean control reaction time of 4–6 s. The cut-off time was adjusted at 15 s in order to avoid tissue damage. The tail-flick latency for each rat was evaluated three times, and the mean value was considered to be the baseline latency. A decreased tail-flick latency represents hyperalgesia as a marker of neuropathy. The nociception threshold was measured once a week for all groups during the entire experimental period.

Rotarod treadmill

The motor coordination of the rats was assessed using the rotarod treadmill test. Rats were placed on the rotating rod device for two trials (on day zero and on the final day of the study). They were first trained to maintain themselves on the rotating rod for more than 3 min, and then they were scored for falling latency (in seconds) in each trial.

Tissue extraction and preparation

Rats were anesthetized by CO2 inhalation and decapitated. The spinal column was cut through the pelvic girdle. Hydraulic extrusion was achieved by inserting a 16 gauge needle into the sacral vertebral canal and injecting ice-cold saline. The spinal cord tissue thus obtained was immediately placed on ice in a glass petri dish and the dorsal half of the lumbar cord dissected. Tissue samples were weighed, immediately frozen and stored in liquid nitrogen tank until assay.

Western blot analysis

Cleaved caspase 3, Bax and Bcl-2 proteins, all important biochemical markers of apoptosis, were evaluated by western blotting. The dissected spinal tissues were homogenized in ice-cold buffer containing 10 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), 1 mM EDTA, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 0.1% Na deoxycholate, 1% NP-40 with protease inhibitors (1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 2.5 µg/ml of leupeptin, 10 µg/ml of aprotinin) and 1 mM sodium orthovanadate. The homogenate was then centrifuged at 14,000 rpm for 15 min at 4 °C, and the resulting supernatant was retained as the whole-cell fraction. Protein concentrations were evaluated using the Bradford method (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA, USA). Equal amounts of protein were resolved electrophoretically on a 9% SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis system and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences, Chicago, IL, USA). After blocking (overnight at 4 °C) with 5% non-fat dried milk in Tris-buffered saline with Tween 20 (blocking buffer, TBS-T, 150 mM NaCl, 20 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 0.1% Tween 20), the membranes were probed with caspase 3 rabbit monoclonal antibody (Asp175 [Cell Signaling Technology; 1:1000 overnight at 4 °C]), Bax (D 21; sc-6236) and Bcl-2 (C-2; sc-7382 [Santa Cruz Biotechnology; 1:1000 for 3 h at room temperature). After washing in TBS-T (three times, 5 min), the blots were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with a horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody (1:15000; GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences). All antibodies were diluted in blocking buffer. The antibody–antigen complexes were detected using the ECL (enhanced chemiluminescence) system and exposed to Lumi-Film chemiluminescent detection film (Roche Diagnostics GmbH, Mannheim, Germany). β-Actin immunoblotting (1:1000; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, USA) was used as a loading control. Caspase 3, Bax, Bcl-2 and β-actin band densities were evaluated from the respective band densitometry. The ImageJ image processing program was used to analyze the intensity of expression. These values were expressed as the tested protein/β-actin ratio for each sample.

Statistical analysis

The results were expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean. The difference in mean tail-flick latency was determined by two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). The differences in motor deficit (mean retention time) and the average caspase3/β-actin and Bax/Bcl-2 band density ratios were compared by one-way ANOVA. The serum glucose level and body weight of experimental groups were compared at the start and end of study using the paired Student’s t test or a one- or two-way repeated measure ANOVA for multiple group comparisons. Tukey’s post hoc test was used following ANOVA to test for significance among the different groups. P < 0.05 was considered to be significant.

Results

The effect of RE on serum glucose level and body weight in diabetic animals

One week following STZ injection, diabetic rats developed hyperglycemia. At this time point the serum glucose concentrations were significantly increased in the non-treated diabetic animals (334.2 ± 12.34 mg/dl; Diabetes group in Table 1) compared to the control animals (92.33 ± 2.418 mg/dl; Control group in Table 1) (P < 0.001). At 4 weeks after STZ injection the plasma glucose levels were also high in the diabetic rats (Table 1). In STZ-treated animals which had received the vehicle (Diabetes + saline group), the serum glucose concentration was similar to that in the non-treated Diabetes group. Once-daily treatment of diabetic rats with 200 mg/kg RE for 3 weeks significantly decreased the serum glucose level compared to the level at the start of RE administration (P < 0.01), but the serum glucose concentration remained much higher than that of the Control group (Table 1). Conversely, treatment with 100 and 150 mg/kg RE had no significant effect on the serum glucose levels of the diabetic animals. The changes in the body weights of the control, diabetic and RE-treated rats during the time course of the study is also shown in Table 1. A significant weight loss was observed in non-RE-treated diabetic rats and those treated with 100 mg/kg RE. Treatment of diabetic animals with 200 mg/kg RE for 3 weeks significantly increased the body weight compared to that at the start of the RE treatment (P < 0.05).

The effect of RE on the nociceptive threshold in diabetic animals

As shown in Fig. 1, saline-treated or non-treated diabetic animals showed a significant decrease in nociceptive threshold (hyperalgesic response) which began 2 weeks (14 days) after STZ injection and persisted almost unchanged up to the end of the study (week 4). RE (200 mg/kg) treatment was observed to reduce the development of diabetes-induced hyperalgesia (Fig. 1).

Effect of rosemary extract (RE) on the progress of diabetes-induced thermal hyperalgesia. Lines indicate nociceptive threshold of each experimental group. Values are presented as mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM) of n = 6–8 animal. Asterisks indicate significant difference (*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001) vs. control groups. Hashtag indicates significant difference (#P < 0.05) vs. diabetic group at the same time point

The effect of RE on diabetes-induced motor deficits

The rotarod treadmill assessment showed that there was a notable loss of motor coordination in diabetic animals. The retention time of the diabetic rats on the rotating rod was decreased to about 64% of that of the non-diabetic (Control) animals, while treatment with 200 mg/kg RE increased the retention time to 93.37% of the control values. RE given at a dose of 100 mg/kg RE had no significant effect on diabetes-induced motor impairment (Fig. 2).

The effect of RE on apoptotic parameters in diabetic animals

Western blotting data showed that diabetes leads to caspase 3 activation in the dorsal portion of the lumbar spinal cord, while RE treatment (200 mg/kg) reduces hyperglycemia-induced caspase 3 activation (Fig. 3). Furthermore, an increase in Bax protein levels was induced under diabetic conditions. Thus, there was a significant increase in the Bax:Bcl-2 protein ratio in diabetic animals. This increased Bax:Bcl-2 ratio was attenuated in diabetic rats treated by 200 mg/kg RE. RE administered at doses of 100 and 150 mg/kg RE had no significant effects on cleaved caspase 3 activation or Bax:Bcl2 ratio expression (Figs. 3, 4).

Western blot analysis of cleaved-caspase 3 in the dorsal portion of lumbar spinal cord. Values are presented as the mean ± SEM band density ratio for each group. Beta-actin (B-actin) was used as an internal control. Asterisks indicate significant difference (*P < 0.05, ***P < P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001) vs. control group. Hashtags indicate significant difference (##P < 0.01) vs. diabetic groups

Western blot analysis of Bax:Bcl2 ratio in dorsal portion of the lumbar spinal cord. Values are presented as the mean ± SEM band density ratio for each group. Beta-actin (B-actin) was used as an internal control. Asterisk indicates significant difference (*P < 0.05) vs. control group. Hashtag indicates significant difference (#P < 0.01) vs. diabetic and diabetic groups

Discussion

Our results show that RE exerted effects that reduced cell damage induced by high glucose levels and inhibited both diabetic neuropathic pain and motor coordination deficit. Administration of RE to diabetic rats reduced the levels of apoptosis markers, such as caspase 3 activation and the Bax:Bcl-2 ratio. We therefore conclude that RE modulated the cellular toxicity in the lumbar spinal cord of diabetic rats induced by high glucose levels.

One of the most common complications of diabetes mellitus is neuropathic pain. Hyperglycemia-induced cell death in STZ-induced diabetic animals represents a good, practical in vivo model for the study of diabetic neuropathic pain [20, 21]. It is now well established that diabetes is associated with advanced oxidative stress [22] and that oxidative stress causes direct toxic effects on nerve tissue [1]. This knowledge has led researchers to study the influence of various antioxidant-based treatments on redox status in several investigational models of diabetes. It is also well documented that oxidative stress is closely linked to apoptosis in a variety of cell types [23]. Many pathological mechanisms, such as intracellular redox homeostasis disruption and irreversible oxidative modifications of lipids, proteins or DNA, can result from oxidative stress and therefore lead to apoptosis. In addition, apoptosis plays a critical role in the development of diabetic neuropathy through oxidative stress [1].

Many in vivo and in vitro studies have shown that pro-apoptotic Bax protein expression increases in hyperglycemic conditions compared to the normal state (i.e. the Bax:Bcl2 ratio is increased) [9, 20, 24]. Bax is a pro-apoptotic member of the Bcl2 family of pro- and anti-apoptotic proteins.

We have recently observed that in PC12 cells cultured in high-glucose media (as an in vitro model of diabetic neuropathy), RE was able to prevent hyperglycemia-induced cellular toxicity by reducing the levels of some biochemical markers of apoptosis, such as caspase 3 activation and the Bax/Bcl2 ratio [25].

In an in vitro investigation, Sharifi and colleagues demonstrated that the suppression of apoptotic proteins by Z-VAD-FMK (as a caspase inhibitor) inhibits the cell toxicity induced by high glucose levels [26]. Joseph and Levine reported that caspases (as components of apoptosis signaling pathways) contribute to the expression of pain-related behavior in animals with peripheral neuropathy. These authors also reported that caspase inhibitors (such as Z-VADFMK) decrease neuropathic pain-related behaviors in rats [27]. Although all mechanisms of diabetic neuropathic pain are not completely known, some animal models indicate that axonal degeneration following peripheral nerve injury causes neuropathic pain [28].

In recent years, much attention has been directed to herbal polyphenolic compounds because they can promote a number of antioxidative mechanisms and stimulate protective enzymes, which result in protection against oxidative cell damage [29]. Rosmarinus officinalis L. (family Lamiaceae) is a perennial herb that is native to the Mediterranean area. In folk medicine, the aerial portions of this herb are mostly used as an analgesic for renal and abdominal colic pain and rheumatic disorders [30, 31]. Rosemary also has several important biological characteristics, such as hepatoprotective [32], antidiabetic [33], anti-oxidant [33] and neuroprotective [19] effects.

It has been reported that the rosemary plant possesses considerable antioxidant activity, and its extract has been shown to exhibit significant radical-scavenging properties, probably due to the high concentration of polyphenolic components such as carnosol, rosmanol, carnosic acid, methyl carnosate, caffeic acid and rosmarinic acid [14]. The RE has also been shown to exert an anti-nociceptive effect in several investigational models of pain [15, 16, 34]. In this background, Ghasemzadeh and colleagues have shown that the extract of the aerial parts of R. officinalis L. can attenuate the neuropathic pain, inflammation and apoptosis induced by chronic constriction injury (CCI) model of neuropathic pain in rats [17, 18]. These authors concluded that by decreasing some apoptotic factors (such as the Bax/Bcl2 ratio as well as cleaved caspase 3 expression in sciatic nerve tissue), the RE can attenuate neuronal damage and neuropathic pain in CCI rats [17, 18].

Taken together, the analgesic effects of rosemary might be mediated through the attenuation of neuronal apoptosis. The neuroprotective properties of this extract may be due, at least in part, to the large amounts of phenolic and flavonoid compounds and to the antioxidant, anti-inflammatory or free radical-scavenging properties of this plant.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the results of this study showed that the leaf extract of R. officinalis has neuroprotective effects, as confirmed by behavioral tests and biochemical assays in a rat model of diabetes. The extract had a significant effect on the reduction of thermal hyperalgesia in STZ-induced diabetic animals.

References

Edwards JL, Vincent AM, Cheng HT, Feldman EL (2008) Diabetic neuropathy: mechanisms to management. Pharmacol Ther 120:1–34

Vinik AI, Nevoret M-L, Casellini C, Parson H (2013) Diabetic neuropathy. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 42:747–787

Várkonyi T, Körei A, Putz Z et al (2017) Advances in the management of diabetic neuropathy. Minerva Med 108:419–437. https://doi.org/10.23736/S0026-4806.17.05257-0

Kamboj SS, Vasishta RK, Sandhir R (2010) N-acetylcysteine inhibits hyperglycemia-induced oxidative stress and apoptosis markers in diabetic neuropathy. J Neurochem 112:77–91

Malone JI (2016) Diabetic central neuropathy: CNS damage related to hyperglycemia. Diabetes 65:355–357

Shima T, Jesmin S, Matsui T et al (2018) Differential effects of type 2 diabetes on brain glycometabolism in rats: focus on glycogen and monocarboxylate transporter 2. J Physiol Sci 68:69–75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12576-016-0508-6

Russell JW, Golovoy D, Vincent AM et al (2002) High glucose-induced oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in neurons. FASEB J 16:1738–1748

Rasoulian B, Kheirandish F (2017) Herbal medicines: from traditional medicine to modern experimental approaches. Herb Med J 2(1):1–2

Kaeidi A, Taati M, Hajializadeh Z et al (2015) Aqueous extract of Zizyphus jujuba fruit attenuates glucose induced neurotoxicity in an in vitro model of diabetic neuropathy. Iran J Basic Med Sci 18:301

Zeng K, Li M, Hu J et al (2017) Ginkgo biloba extract EGb761 attenuates hyperhomocysteinemia-induced AD like tau hyperphosphorylation and cognitive impairment in rats. Curr Alzheimer Res. https://doi.org/10.2174/1567205014666170829102135

Ablat N, Lv D, Ren R et al (2016) Neuroprotective effects of a standardized flavonoid extract from safflower against a rotenone-induced rat model of Parkinson’s Disease. Molecules 21(9). https://doi.org/10.3390/molecules21091107

Tavafi M, Ahmadvand H (2011) Effect of rosmarinic acid on inhibition of gentamicin induced nephrotoxicity in rats. Tissue Cell 43:392–397

Ramadan KS, Khalil OA, Danial EN et al (2013) Hypoglycemic and hepatoprotective activity of Rosmarinus officinalis extract in diabetic rats. J Physiol Biochem 69:779–783

Vicente G, Molina S, González-Vallinas M et al (2013) Supercritical rosemary extracts, their antioxidant activity and effect on hepatic tumor progression. J Supercrit Fluids 79:101–108

González-Trujano ME, Peña EI, Martínez AL et al (2007) Evaluation of the antinociceptive effect of Rosmarinus officinalis L. using three different experimental models in rodents. J Ethnopharmacol 111:476–482

Martínez AL, González-Trujano ME, Pellicer F et al (2009) Antinociceptive effect and GC/MS analysis of Rosmarinus officinalis L. essential oil from its aerial parts. Planta Med 75:508–511

Ghasemzadeh MR, Amin B, Mehri S et al (2016) Effect of alcoholic extract of aerial parts of Rosmarinus officinalis L. on pain, inflammation and apoptosis induced by chronic constriction injury (CCI) model of neuropathic pain in rats. J Ethnopharmacol 194:117–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jep.2016.08.043

Ghasemzadeh Rahbardar M, Amin B, Mehri S et al (2017) Anti-inflammatory effects of ethanolic extract of Rosmarinus officinalis L. and rosmarinic acid in a rat model of neuropathic pain. Biomed Pharmacother Biomed Pharmacother 86:441–449. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopha.2016.12.049

Seyedemadi P, Rahnema M, Bigdeli MR et al (2016) The neuroprotective effect of rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) hydro-alcoholic extract on cerebral ischemic tolerance in experimental stroke. Iran J Pharm Res 15:875–883

Kaeidi A, Esmaeili-Mahani S, Abbasnejad M et al (2013) Satureja khuzestanica attenuates apoptosis in hyperglycemic PC12 cells and spinal cord of diabetic rats. J Nat Med 67:61–69

Guo J, Fu X, Cui X, Fan M (2015) Contributions of purinergic P2X3 receptors within the midbrain periaqueductal gray to diabetes-induced neuropathic pain. J Physiol Sci 65:99–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12576-014-0344-5

Behl T, Kaur I, Kotwani A (2016) Implication of oxidative stress in progression of diabetic retinopathy. Surv Ophthalmol 61:187–196

Orrenius S, Gogvadze V, Zhivotovsky B (2007) Mitochondrial oxidative stress: implications for cell death. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 47:143–183

Hajializadeh Z, Nasri S, Kaeidi A et al (2014) Inhibitory effect of Thymus caramanicus Jalas on hyperglycemia-induced apoptosis in in vitro and in vivo models of diabetic neuropathic pain. J Ethnopharmacol 153:596–603

Rashidipour M, Hajializad Z, Esmaeili-Mahani S, Kaeidi A (2017) The effect of Rosmarinus officinalis L. extract on the inhibition of high glucose-induced neurotoxicity in PC12 Cells: an in vitro model of diabetic neuropathy. Herb Med J 2:114–1121

Sharifi AM, Eslami H, Larijani B, Davoodi J (2009) Involvement of caspase-8,-9, and-3 in high glucose-induced apoptosis in PC12 cells. Neurosci Lett 459:47–51

Joseph EK, Levine JD (2004) Caspase signalling in neuropathic and inflammatory pain in the rat. Eur J Neurosci 20:2896–2902

Jensen TS, Finnerup NB (2014) Allodynia and hyperalgesia in neuropathic pain: clinical manifestations and mechanisms. Lancet Neurol 13:924–935

Rajendran P, Nandakumar N, Rengarajan T et al (2014) Antioxidants and human diseases. Clin Chim Acta 436:332–347. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2014.06.004

Al-Sereiti MR, Abu-Amer KM, Sen P (1999) Pharmacology of rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) and its therapeutic potentials. Indian J Exp Biol 37:124–130

Martínez AL, González-Trujano ME, Chávez M, Pellicer F (2012) Antinociceptive effectiveness of triterpenes from rosemary in visceral nociception. J Ethnopharmacol 142:28–34

Amin A, Hamza AA (2005) Hepatoprotective effects of Hibiscus, Rosmarinus and Salvia on azathioprine-induced toxicity in rats. Life Sci 77:266–278

Bakırel T, Bakırel U, Keleş OÜ et al (2008) In vivo assessment of antidiabetic and antioxidant activities of rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) in alloxan-diabetic rabbits. J Ethnopharmacol 116:64–73

Emami F, Ali-Beig H, Farahbakhsh S et al (2013) Hydroalcoholic extract of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) and its constituent carnosol inhibit formalin-induced pain and inflammation in mice. Pak J Biol Sci 16:309–316

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants from the Razi Herbal Medicines Research Center, Lorestan University of Medical Science (Grant Numbers 221393).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Author contributions

AK, BR and SEM conceived and designed the experiments. BR, AK, ZH, MR and IF performed the experiments. AK and BR analyzed the data. BR and AK contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools. AK, BR and ZH wrote the paper

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors report no conflict of interest.

About this article

Cite this article

Rasoulian, B., Hajializadeh, Z., Esmaeili-Mahani, S. et al. Neuroprotective and antinociceptive effects of rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) extract in rats with painful diabetic neuropathy. J Physiol Sci 69, 57–64 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12576-018-0620-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12576-018-0620-x