Abstract

Political participation can be regarded as a basic need in democracies. After a worrying 2016, a year of populism and post-truth politics, two different narratives for the future have emerged: one optimistic, the other pessimistic. The former refers to a growing pro-European spirit and the arrival of a new civic culture, epitomised by movements such as Pulse of Europe. The latter sees the worrying growth of fake news and the decline of traditional institutions, as well as the rise of authoritarian tendencies, which seems to indicate that political engagement is seen as old-fashioned. In any case, today’s reality in this age of new technology requires a project- and network-based approach.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The year 2016 was an annus horribilis and acted as a warning about the new reality of post-truth politics. It included Brexit, the refugee crisis, the fear of Islamist terrorism with numerous and ongoing attacks, the rise of right-wing populist parties and, more generally, authoritarian developments on a global scale. Some visions for the future have already turned out to be, or will be seen to have been, illusions: the imminent enlargement of the EU, including Turkey, Ukraine and the Western Balkans; and the creation of a European plan for the distribution of refugees. In his September 2017 State of the Union speech, Jean-Claude Juncker proposed the following: ‘If we want the euro to unite rather than divide our continent, then it should be more than the currency of a select group of countries. The euro is meant to be the single currency of the European Union as a whole’ (Juncker 2017). The question thus arises: What do these dramatic political changes mean for political participation? They have opened the floor to two interpretations.

First, there is the optimistic one. Events such as the shock of Brexit and the challenge of migration have led to new forms of civic culture and basic grassroots movements in a ‘wind of change’. The second interpretation, the pessimistic one, refers to the growing distrust of representative democracy and party politics, and marks a new ‘end of history’. In the following, I want to discuss the basic concept of political participation before I turn to an analysis of the optimistic and pessimistic narratives. We should understand that political participation is the interaction of citizens with political parties or institutions. From the centre–right perspective, which stresses the merits of both tradition and modernity, this is based on Christian values such as solidarity and subsidiarity.

Forms of political participation

One of the features of democracies is that citizens are provided with a lot of opportunities for their interests to be incorporated into the political process. As well as participating in elections, they can, among other things, work for political parties, take part in civic initiatives, sign petitions, boycott certain products for political reasons, participate in demonstrations, donate money to political organisations, take part in civil disobedience or run for public office. Civic engagement conventionally refers to actions by ordinary citizens that are intended to influence wider society, that is, those outside their own family and circle of close friends. Political organisations encourage supporters to engage in these forms of behaviour via digital platforms. Political parties and non-governmental and civil society organisations attempt to draw citizens into promoting their campaigns, harnessing their dedication to a cause or the organisation. In times of populism, this also opens the door for old and classical mobilisation tools, such as door-to-door-campaigning. Indeed, the German ruling party, the Christian Democratic Union (Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands), has successfully returned to door-to-door campaigning. It has a modern component, however: technical support is provided via apps and data analysis. This initiative, called ‘Connect 2017’, has created a feedback loop between the party’s headquarters and door-to-door volunteers (Deutsche Welle 2017).

New forms of political participation should be inclusive, not exclusive. Spreading fear about migrants and refugees (as has occurred due to the urgent need for their fair distribution across Europe) is certainly exclusive, as the political campaigns based on fear in Poland, Hungary and Slovakia since the autumn of 2015 have shown. To unlock the mysteries of political engagement, it is important to have a closer understanding of an individual’s motivation—there is more psychology and less economics involved here. Anger, euphoria and moral outrage are one side of this coin; courage, bravery and, last but not least, hard work, as well as employment, are the other. The new digital decision-making process shortens the distance between the so-called political elites and the people, regardless of their level of technical sophistication.

Participation is derived from motivation, which can take several concrete forms (Ekman and Amnå 2012, 292):

-

personal interest in politics,

-

electoral participation,

-

unlawful acts,

-

a sense of belonging to a group (collective identity),

-

voluntary work,

-

party politics,

-

a start-up approach: creating one’s own platforms and digital tools,

-

organised political participation, and

-

network- or project-based participation.

In the new world of digital politics, e-participation offers new possibilities, such as producing webcasts and podcasts; responding to surveys; participating in web-portals, chat rooms, polls and decision-making games; and e-petitioning and e-voting. The latter, first introduced nationwide in Estonia in 2005, does not automatically increase turnout, as experience has proven. Across Europe many e-participation projects have been funded in recent years, but the effects and impacts of them are not very clear. The extent to which people are motivated through the mobilisation strategies of both political organisations and peers within their networks via social media is an issue of some debate. The mobilisation thesis argues that access to digital technologies has the capacity to draw new participants into civic life, particularly among younger citizens. In reality, however, studies often find mixed results, with digital technologies facilitating reinforcement and mobilisation among particular user groups of digital platforms (Nam 2012). Due to the mélange of beliefs and scepticism that exists regarding the future, the rest of the article will look at both the optimistic and the negative possible narratives.

The optimistic narrative

After the events of 2016, some observers have commented that the populist wave has reached its zenith. The election of US President Donald Trump, who has clearly stated that he supports Brexit and does not care if the removal of the UK from the EU (the stepping down of the second biggest economic power in the EU) brings a new ‘end of history’. Eurosceptics have made such a loud noise that it has acted as a wake up-call for the silent pro-European majority. Going to vote matters: this is the lesson learned in and beyond the UK. About three-quarters of 18- to 24-year-olds who voted cast ballots for Remain, while three in five of the over-60s opted to Leave, surveys show. However, only 36% of people between 18 and 24 years participated; and of those between 25 and 34 years old, only 58% voted; whereas 83% of those who are 65 and older voted (Henn and Sharpe 2016).

However, in reaction to the Brexit vote, a new movement called Pulse of Europe has started to advocate for the European project. It was founded in Frankfurt at the end of 2016 and is organised through personal networks, social media and voluntary donations. The movement’s slogan could be described as, ‘Unite, Unite Europe! A Protest in Favor of the European Union’, which is the title of an article in the New Yorker about it: ‘So far, most Pulse of Europe demonstrations are located in Germany, though gatherings have taken place in towns from Montpellier to Stockholm, and organisers say queries have come in from Warsaw and Budapest’ (McGrane 2017). Within just half a year, thousands of people have gathered in 130 cities and 19 countries. Since February 2017, demonstrations have taken place every Sunday in various locations, including in Albania and Ukraine. Tirana and Kyiv have both registered as ‘Pulse of Europe’ cities—a sign that they want to be part of the pro-European push too.

Unlike previous pro-EU movements, Pulse of Europe is a grassroots, decentralised organisation with no links to the Brussels-based institutions. And, unlike most movements, Pulse of Europe is not against, but for something: a European community of shared values. The creators of Pulse of Europe, who work for a legal company, believe in a liberal, fully supranational EU. The official website calls for activism: ‘Come on, grab your European flag and blue ribbons, bring your friends and family, and motivate your colleagues. Become active and join Pulse of Europe close to you!’ (Pulse of Europe 2017). The idea of standing up for Europe sounds very reasonable and perfectly timed. It appears that the clear goal of the movement, like that of many social movements, can be judged independently from its success. So far politicians have not been permitted to get involved in the demonstrations in order to allow the movement to retain its label as an independent movement.

Symbolically, Pulse of Europe fulfils the criteria for the current form of political engagement: it is organised via social media, operates like a business and stands for a particular issue—the success of the European project. In addition, it represents the new Zeitgeist in modern democracies, as is reflected by political leaders such as German Chancellor Angela Merkel: it is not too concrete in form and is only a little ideological, instead appealing to emotions and offering a positive vision. The mechanisms of democratic representation play only a side role in this regard. The movement’s public relations strategy has been so successful that Pulse of Europe has received a civic prize from the editors of German newspapers. It seems that it is the first clear social movement fighting exclusively for the deepening of the EU. The whole idea fits well with the idea of network- and project-based participation.

The British think tank Demos conducted an opinion poll based on the UK general election in 2015—before the Brexit referendum. A large majority (72%) of people who had used social media for political purposes reported that they felt more politically engaged as a direct result. Over a third (39%) of the poll’s respondents who had engaged with political content on social media felt more likely to vote as a direct result (Miller 2016, 11). However, the result of the Brexit referendum showed how poorly mobilised young people were to vote. But there is no doubt that the use of digital technologies can provide pathways to higher participation levels.

If we really are living in an age of anti-politics, political decision-makers can address this problem. In a rare touch of humour in the dour world of politics, the Spanish anti-austerity, left-wing radical party Podemos (We Can!) published its manifesto in the style of the Ikea catalogue. As in the Swedish furniture catalogue, the manifesto is organised on a room-by-room basis, with candidates pictured at home in the kitchen, on the sofa, in the garden or working at their desks in homely, affordable and cosy-looking spaces. Party members are depicted feeding their fish, hanging out the washing, making the bed and brushing their teeth. The goal was to produce the most-read manifesto ever produced (The Guardian 2016). With this campaign idea, the claim of ‘bringing democracy back to the people’ found a response.

The pessimistic narrative

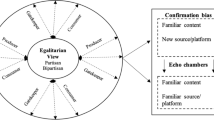

The spread of the Internet and related new tools since the 1990s had reinvigorated great hopes for a revitalisation of Western democracies. However, the great visions of cyberspace as an ‘electronic frontier’ of free thought and political activity have undergone a reality check. The fragmentation and unpredictability of public opinion has been seen in the false prognoses of opinion polls on Brexit, the election of President Trump and on many other occasions. An ongoing and deepening protest culture, based on the idea of ‘citizens in anger’ and political alienation from the established ways of democracy is challenging liberal democracies (Hartleb 2011). It even seems as though the political discourse only consists of fake news, hate and conspiracy theories. Kellyanne Conway, adviser to President Trump, created the phrase ‘alternative facts’ to describe demonstrable falsehoods in the context of Trump’s inauguration on 22 January 2017. Facebook itself has published a detailed and precise study on civic engagement that discusses possible counter-measures. It states:

The networks of politically-motivated false amplifiers and financially-motivated fake accounts have sometimes been observed commingling and can exhibit similar behaviors; in all cases, however, the shared attribute is the inauthenticity of the accounts. . . . In some instances dedicated, professional groups attempt to influence political opinions on social media with large numbers of sparsely populated fake accounts that are used to share and engage with content at high volumes. (Weeden et al. 2017, 8)

A concrete example would be the ‘Lisa’ case in Germany, which dominated the headlines and affected German public discussion for two weeks in January 2016. The 13-year-old Russian–German girl had gone missing for several hours and was reported by First Russian TV to have been raped by migrants. The story turned out to be fake (she had been with a friend that night, according to the police investigation) but was extensively reported in the Russian media, including by Russia Today and Sputnik. The Kremlin accused Germany, of ‘sweeping the case under the carpet’ (BBC 2016) and Russian–Germans went out onto the streets and gathered in front of the Kanzleramt (German Chancellery) to protest. This example shows how easily the masses can be manipulated.

In the US and Europe there is an image of the ‘angry white man’, who believes in a strong leader and who propagates the idea of a national disaster in various dimensions as part of a cultural ‘clash of civilisations’. On this, the Frenchman Gustave Le Bon, who published the famous book The Crowd: A Study of the Popular Mind at the end of the nineteenth century, still offers food for thought. Crowds, being incapable both of reflection and of reasoning, possess a collective mind (Le Bon 2016). Anti-politics, the rejection of traditional politics and its practitioners, is a popular instinct today. The rising support for populist parties has disrupted the politics of many Western societies. Populist mobilisation can be defined as ‘any sustained, large-scale political project that mobilises ordinarily marginalised social sectors into publicly visible and contentious political action, while articulating an anti-elite, nationalist rhetoric that valorises ordinary people’ (Jansen 2011, 84).

The fact that even in Germany, for the first time in post-war history, a radical right-wing party—Alternative for Germany (Alternative für Deutschland, AfD)—has entered the national parliament has its roots, not in the economy, but in a cultural backlash, based on a fear of migration and refugees. In its short history the AfD has rapidly morphed from being a ‘professors’ party’ of Eurosceptic economists to one focused on nationalist conservatism and anti-migration policies, similar to other European populist parties such as the Freedom Party of Austria (Freitheitliche Partei Österreichs) and the French National Front (Front National). The AfD has been very successful at consolidating the anti-establishment vote and mobilising people who had not voted in previous elections. Exit polls from regional elections since the last federal election four years ago show that the party has drawn large parts of its support from minor parties and by rallying those who have never previously voted (Stabe and Maier-Borst 2017). The party’s success reflects the basic strategic mistake of established parties—demonising their populist competitors. The mobilisation of an anti-populist campaign, including constant attacks on populist parties and openly excluding them from public debates, has brought such parties attention and has laid the floor open to a counter-mobilisation that requires little effort and few resources (Hartleb 2017, 165–93). Given that the highly emotive issue of migration and the refugee challenge is likely to remain unresolved in European politics, populist parties are easily able to play on people’s fears and build up resentment. Comparative studies see migration as a much more important factor for populism than socio-economic differences (Inglehart and Norris 2016). In other words: it is not just the ‘losers of modernisation’ who vote for populist parties.

Another worrying factor lies in the nature of democracies itself. The longitudinal data of the World Values Survey indicates that there is widespread disillusion with the Western model of liberal democracy (World Values Survey Wave 1–6, 2017). Citizens in a number of supposedly consolidated democracies in North America and Western Europe have not only grown more critical of their political leaders, but have also become more cynical about the value of democracy as a political system. They are less hopeful that anything they do might influence public policy and more willing to express support for authoritarian alternatives. The authors conclude that young people engage in lower numbers than previous cohorts did at the same age. This decline in political engagement is even more marked for measures such as active membership of new social movements (Foa and Mounk 2016, 7; 11). The rise of populism is connected with the changing framework for political parties, which are facing problems of disenchantment. This affects old democracies as well: the declines in party membership and voter turnout are opening up the space for business-oriented types of political parties and simple protest platforms (Hartleb 2012).

Conclusion

Participation in politics can never be fairly distributed or balanced among criteria such as age, income and gender. However, the new reality in the age of new technologies demands a project- and network-based approach that goes beyond the traditional ways of working. Simply mobilising against populism has too little potential for success. We must face the new realities, regardless of whether our outlook is optimistic or pessimistic. This means we must

-

promote the mechanism of representative democracy,

-

advertise the European idea,

-

listen to the electorate and treat social media as a two-way street, and

-

create a political sphere that exists beyond simple (and anonymous) online discussions.

Organised political participation should be based on the following pillars: representation, transparency, and a well-balanced mixture of conflict and consensus. Every political engagement campaign needs a clear team structure for the volunteer operation and a framework for motivation. As Moisés Naím (2017) points out in the New York Times, political parties cannot give up their monopoly of mobilisation: ‘Political parties must regain the ability to inspire and mobilize people—especially the young—who might otherwise disdain politics or prefer to channel whatever political energy they have through single-issue groups.’

References

BBC. (2016). Russia steps into Berlin ‘rape’ storm claiming German cover-up. 27 January. http://www.bbc.com/news/blogs-eu-35413134. Accessed 23 October 2017.

Deutsche Welle. (2017). German election: Parties return to door-to-door campaigning. 10 August. http://www.dw.com/en/german-election-parties-return-to-door-to-door-campaigning/a-40045887. Accessed 19 September 2017.

Ekman, J., & Amnå, E. (2012). Political participation and civic engagement: Towards a new typology. Human Affairs, 22(3), 283–300.

Foa, R. S., & Mounk, Y. (2016). The democratic disconnect. Journal of Democracy, 27(3), 5–17.

Hartleb, F. (2011). A new protest culture in Western Europe? European View, 10(1), 3–10.

Hartleb, F. (2012). All tomorrow’s parties: The changing face of European party politics. Brussels: Centre for European Studies.

Hartleb, F. (2017). Die Stunde der Populisten. Wie sich unsere Politik trumpetisiert und was wir dagegen tun können. Schwalbach/Ts: Wochenschau-Verlag.

Henn, M., & Sharpe, D. (2016). Young people in a changing Europe: British youth and Brexit 2016. EU Referendum Analysis 2016. http://www.referendumanalysis.eu/eu-referendum-analysis-2016/section-8-voters/young-people-in-a-changing-europe-british-youth-and-brexit-2016/. Accessed 1 September 2017.

Inglehart, R., & Norris, P. (2016). Trump, Brexit and the rise of populism. Economic have-nots and cultural backlash. Harvard Kennedy School Working Paper RWP16-026, Cambridge, Massachusetts, August. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2818659. Accessed 1 September 2017.

Jansen, R. S. (2011). Populist mobilization: A new theoretical approach to populism. Sociological Theory, 29(2), 75–96.

Juncker, J.-C. (2017). ‘Introduction—Wind in Our Sails’. State of the Union speech, Brussels, 13 September. http://europa.eu/rapid/press-release_SPEECH-17-3165_en.htm. Accessed 20 September 2017.

Le Bon, G. (2016). Psychologie der Massen. Hamburg: Nikol. (German translation, first published in French in 1895).

McGrane, S. (2017). Unite, unite Europe! A protest in favor of the European Union. New Yorker, 19 April. https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/unite-unite-europe-a-protest-in-favor-of-the-european-union. Accessed 19 September 2017.

Miller, C. (2016). ‘We are living through a radical shift in the nature of political engagement..’: The rise of digital politics. London: Demos.

Naím, M. (2017). Why we need political parties? New York Times, 19 September. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/19/opinion/need-political-parties.html. Accessed 19 September 2017.

Nam, T. (2012). Dual effects of the Internet on political activism: Reinforcing and mobilizing. Government Information Quarterly, 29(1), 90–7.

Pulse of Europe. (2017). Become active. https://pulseofeurope.eu/mitmachen/aktiv-werden/. Accessed 1 September 2017.

Stabe, M., & Maier-Borst, H. (2017). German election. AfD’s advance in six charts. Financial Times, 20 September. https://www.ft.com/content/1e3facea-9d48-11e7-8cd4-932067fbf946. Accessed 20 September 2017.

The Guardian. (2016). Flat-pack policies: New Podemos manifesto in style of Ikea catalogue. 9 June. https://www.theguardian.com/world/2016/jun/09/podemos-manifesto-ikea-catalogue-flat-pack-policies. Accessed 2 September 2017.

Weeden, J., Nuland, W., & Stamos, A. (2017). Information operations and Facebook. Menlo Park, California, 27 April. https://fbnewsroomus.files.wordpress.com/2017/04/facebook-and-information-operations-v1.pdf. Accessed 2 September 2017.

World Values Survey Wave 1–6. (2017). 1981–2016. http://www.worldvaluessurvey.org/WVSDocumentationWV6.jsp. Accessed 2 September 2017.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

This article is published under an open access license. Please check the 'Copyright Information' section either on this page or in the PDF for details of this license and what re-use is permitted. If your intended use exceeds what is permitted by the license or if you are unable to locate the licence and re-use information, please contact the Rights and Permissions team.

About this article

Cite this article

Hartleb, F. Political participation today: a radical shift, but with a positive or negative outcome?. European View 16, 303–311 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12290-017-0458-2

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12290-017-0458-2