Abstract

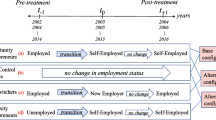

The literature on the self-employed hypothesizes two different paths to self-employment. On the one hand, self-employment is associated with entrepreneurship and a motivation to pursue an opportunity. On the other hand, previous research indicates that people also become self-employed because of limited opportunities in the wage sector. Using a unique set of data that links the American Community Survey to Form 1040 and W-2 records, this paper extends the existing literature by examining self-employment duration for five consecutive entry cohorts, including two cohorts who entered self-employment during the Great Recession. Severely limited labor market opportunities may have driven many in the recession cohorts to enter self-employment, while those entering self-employment during the boom may have been pursuing opportunities under favorable market conditions. To more explicitly test the concept of “necessity” versus “opportunity” self-employment, we also examine the pre-entry wage labor attachment of entrants. Specifically, we ask whether an association exists between wage labor attachment and the duration of self-employment. We also explore whether the demographic/socio-economic characteristics and self-employment exit behavior of the cohorts are different, and if so, how. We find evidence consistent with the existence of “necessity” vs. “opportunity” self-employment types. Even when controlling for local economic conditions and the demographic/socio-economic characteristics of the self-employed, entrants with a more tenuous connection to the wage labor market exit self-employment earlier, and are more likely to transition from self-employment to unemployment.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In contrast to Fairlie and Fossen’s paper, we define four different categories of pre-entry labor market attachment based on the number of weeks worked rather than unemployed/employed.

See https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/ for more information on the ACS.

A sole proprietorship is an unincorporated business owned and run by one individual. A partnership is an unincorporated business owned and run by more than one person.

Results available upon request.

Hurst & Pugsley (2015) offer an additional perspective for why individuals may become entrepreneurs. They emphasize the role of non-pecuniary benefits and entrepreneurs’ tastes for entering self-employment, and how these should be taken into consideration when designing policies aimed at benefiting entrepreneurship.

As mentioned earlier, our identification of opportunity and necessity types is consistent with those in the most recent literature (Fairlie & Fossen, 2018).

It is difficult to categorize 2007 as a boom or recession year since the official start of the Great Recession was December of 2007, and economic conditions deteriorated throughout that year (see Elsby et al., 2010).

See Fairlie & Fossen (2018).

Results showing all groups available upon request.

As mentioned earlier, please note that our self-employed sample does not include incorporated businesses since our tax data provides information only on whether individuals filed schedules C and SE. The exploration of incorporated as well as unincorporated self-employed individuals is left to future work as additional data becomes available.

The percentage of self-employed individuals with one-year gaps in self-employment is approximately 12% in the 2009 cohort, 15% in the 2008 cohort, 17% in the 2007 and 2006 cohorts and 36% in the 2005 cohort.

Statistical significance was determined according to a Chi-squared test. We also examined sex, Hispanic origin, citizenship status, home ownership, and industry, but these did not vary between cohorts.

For example, in 2005 Black alone represented 2.8% and in 2008, 4.4%; in 2005 Asian alone represented 4.2% and in 2008, 4.4%.

For example, in 2005 those with a BS/BA represented 22 and in 2008, 23.1%; the comparable rates for Masters/PhD were 14.2 and 14.8, while for less than a high school degree the comparable rates were 7.8 and 7.1.

In addition to labor market attachment, we also looked at household adjusted gross income and wage and salary income as reported on the 1040 (results available on request). This information reflects resources and labor market attachment at the household, rather than individual, level. We found that earnings and adjusted gross income decreased substantially for self-employment entrants between the 2008 and 2009 cohorts. The same measures for existing self-employed and wage-sector earners also decreased, but not as steeply.

In addition, as mentioned earlier, due to the potential for the pre-entry wage employment status to be endogenously determined, we conduct a sensitivity analysis consisting of a Heckman selection correction. Our results with and without the correction are very similar and do not quantitatively change. Results are available upon request.

Individuals that remain self-employed up to our last time period are treated as right-censored observations.

Because our analytic sample is selected based on attributes that do not enter into the calculation of weights, our logit estimation uses unweighted data.

These results are available upon request.

Specifically, these are averaged predicted probabilities for each group calculated using the actual or observed values of the covariates.

A robustness check indicated that our results were not sensitive to excluding college-age adults from our sample.

The only exception is the 27–39 group for the 2005 cohort in 2008 and 2010.

Results available upon request.

Similarly to the binomial results, a robustness check indicated that our multinomial results were not sensitive to excluding college-age adults from our sample.

References

Ahn T (2011) Racial differences in self-employment exits. Small Bus Econ Springer 36(2):169–186

Behrenz L, Delander L, Månsson J (2016) Is starting a business a sustainable way out of unemployment? Treatment effects of the Swedish start-up subsidy. J Lab Res 37(4):389–411

Block JH, Sandner P (2009) Necessity and opportunity entrepreneurs and their duration in self-employment: evidence from German micro data. J Indust Compet Trade 9:117–137

Block JH, Wagner M (2010) Necessity and opportunity entrepreneurs in germany: characteristics and earnings differentials. Schmalenbach Bus Rev 62(2):154–174

Block JH, Hoogerheide L, Thurik R (2011) Education and entrepreneurial choice: an instrumental variables analysis. Int Small Bus J, vol. 31(1), p23–33

Bosma N (2013) The global entrepreneurship monitor (GEM) and its impact on entrepreneurship research. Found Trends Entrep 9(2)

Carrasco R (1999) Transitions to and from self-employment in Spain: an empirical analysis. Oxford Bull Econ Stat 61(3):315–342

Elsby M, Hobijn B, Şahin A (2010) The labor market in the great recession. Prepared for Brookings Panel on Economic Activity, March 18-19, 2010

Evans DS, Leighton L (1990) Small business formation by unemployed and employed workers. Small Bus Econ, vol. 2(4), p319–330

Fairlie RW (2013) Entrepreneurship, economic conditions, and the great recession. J Econ Manag Strategy 22(2):207–231

Fairlie RW, Meyer BD (1996) Ethnic and racial self-employment differences and possible explanations. J Human Resour 31(4):757–793

Fairlie RW Entrepreneurship among Disadvantaged Groups: An Analysis of the Dynamics of Self-Employment by Gender, Race, and Education,” forthcoming in the Handbook of Entrepreneurship. Parker, Simon D., Zoltan J. Acs, and David R. eds., Audretsch, Kluwer Academic Publishers

Fairlie RW (2007) Entrepreneurship in Silicon Valley during the boom and bust. University of California, Santa Cruz Working Paper at http://people.ucsc.edu/~rfairlie/papers/siliconvalley.pdf

Farber HS (1999) Alternative and part-time employment arrangements as a response to job loss,” (no. w7002). National Bureau of economic research

Haas M, Vogel P (2016) Supporting the transition from unemployment to self-employment—a comparative analysis of governmental support programs across Europe. In Brewer, J. and W. Gibson (eds.) Institutional case studies on necessity entrepreneurship. Edward Elgar

Jarmin RS, Krizan CJ, Luque A (2014) Owner characteristics and firm performance during the great recession. CES working paper no. 14–36. Center for Economic Studies, U.S. Census Bureau, Washington, D.C.

Jarmin RS, Krizan CJ, Luque A (2016) Small business growth and failure during the great recession: the role of house prices, race and gender. CARRA-WP-2016-08. Center for Administrative Records Research & applications, US Census Bureau, Washington, D.C.

Millán JM, Congregado E, Román C (2012) Determinants of self-employment survival in Europe. Small Bus Econ. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-010-9260-0

Poschke M (2013) Who becomes an entrepreneur? Labor market prospects and occupational choice. J Econ Dyn Control 37(3):693–710

Rissman ER (2006) The self-employment duration of younger men over the business cycle. Econ Perspect 30(3):14–27

Wagner D, Layne M (2014) The Person Identification Validation System (PVS): Applying the Center for Administrative Records Research and Applications’ (CARRA) Record Linkage Software. Center for Administrative Records Research and Applications Working Paper, 1

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Luque, A., Jones, M.R. Differences in Self-Employment Duration by Year of Entry & Pre-Entry Wage-Sector Attachment. J Labor Res 40, 24–57 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-018-9275-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12122-018-9275-x

Keywords

- Self-employment

- Entrepreneurship

- Necessity entrepreneur

- Opportunity entrepreneur

- Self-employment duration

- Great recession