Abstract

Eed (embryonic ectoderm development) is a core component of the Polycomb Repressive Complex 2 (PRC2) which catalyzes the methylation of histone H3 lysine 27 (H3K27). Trimethylated H3K27 (H3K27me3) can act as a signal for PRC1 recruitment in the process of gene silencing and chromatin condensation. Previous studies with Eed KO ESCs revealed a failure to down-regulate a limited list of pluripotency factors in differentiating ESCs. Our aim was to analyze the consequences of Eed KO for ESC differentiation. To this end we first analyzed ESC differentiation in the absence of Eed and employed in silico data to assess pluripotency gene expression and H3K27me3 patterns. We linked these data to expression analyses of wildtype and Eed KO ESCs. We observed that in wildtype ESCs a subset of pluripotency genes including Oct4, Nanog, Sox2 and Oct4 target genes progressively gain H3K27me3 during differentiation. These genes remain expressed in differentiating Eed KO ESCs. This suggests that the deregulation of a limited set of pluripotency factors impedes ESC differentiation. Global analyses of H3K27me3 and Oct4 ChIP-seq data indicate that in ESCs the binding of Oct4 to promoter regions is not a general predictor for PRC2-mediated silencing during differentiation. However, motif analyses suggest a binding of Oct4 together with Sox2 and Nanog at promoters of genes that are PRC2-dependently silenced during differentiation. In summary, our data further characterize Eed function in ESCs by showing that Eed/PRC2 is essential for the onset of ESC differentiation.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Young, R. A. (2011). Control of the embryonic stem cell state. Cell, 144, 940–954.

Margueron, R., & Reinberg, D. (2011). The Polycomb complex PRC2 and its mark in life. Nature, 469, 343–349.

Cao, R., Wang, L., Wang, H., et al. (2002). Role of histone H3 lysine 27 methylation in Polycomb-group silencing. Science, 298, 1039–1043.

Pengelly, A. R., Copur, O., Jackle, H., Herzig, A., & Muller, J. (2013). A histone mutant reproduces the phenotype caused by loss of histone-modifying factor Polycomb. Science, 339, 698–699.

Montgomery, N. D., Yee, D., Chen, A., et al. (2005). The murine polycomb group protein Eed is required for global histone H3 lysine-27 methylation. Current Biology, 15, 942–947.

Margueron, R., Justin, N., Ohno, K., et al. (2009). Role of the polycomb protein EED in the propagation of repressive histone marks. Nature, 461, 762–767.

Schoeftner, S., Sengupta, A. K., Kubicek, S., et al. (2006). Recruitment of PRC1 function at the initiation of X inactivation independent of PRC2 and silencing. The EMBO Journal, 25, 3110–3122.

Boyer, L. A., Plath, K., Zeitlinger, J., et al. (2006). Polycomb complexes repress developmental regulators in murine embryonic stem cells. Nature, 441, 349–353.

Chamberlain, S. J., Yee, D., & Magnuson, T. (2008). Polycomb repressive complex 2 is dispensable for maintenance of embryonic stem cell pluripotency. Stem Cells, 26, 1496–1505.

Shen, X., Liu, Y., Hsu, Y. J., et al. (2008). EZH1 mediates methylation on histone H3 lysine 27 and complements EZH2 in maintaining stem cell identity and executing pluripotency. Molecular Cell, 32, 491–502.

Faust, C., Schumacher, A., Holdener, B., & Magnuson, T. (1995). The eed mutation disrupts anterior mesoderm production in mice. Development, 121, 273–285.

Wang, J., Mager, J., Schnedier, E., & Magnuson, T. (2002). The mouse PcG gene eed is required for Hox gene repression and extraembryonic development. Mammalian Genome, 13, 493–503.

Morin-Kensicki, E. M., Faust, C., LaMantia, C., & Magnuson, T. (2001). Cell and tissue requirements for the gene eed during mouse gastrulation and organogenesis. Genesis, 31, 142–146.

Dinger, T. C., Eckardt, S., Choi, S. W., et al. (2008). Androgenetic embryonic stem cells form neural progenitor cells in vivo and in vitro. Stem Cells, 26, 1474–1483.

Dang, S. M., Gerecht-Nir, S., Chen, J., Itskovitz-Eldor, J., & Zandstra, P. W. (2004). Controlled, scalable embryonic stem cell differentiation culture. Stem Cells, 22, 275–282.

Koch, C. M., Reck, K., Shao, K., et al. (2013). Pluripotent stem cells escape from senescence-associated DNA methylation changes. Genome Research, 23, 248–259.

Benjamini, Y., & Hochberg, Y. (1995). Controlling the false discovery rate - a practical and powerful approach to multiple testing. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society Series B-Methodological, 57, 289–300.

Bracken, A. P., Pasini, D., Capra, M., Prosperini, E., Colli, E., & Helin, K. (2003). EZH2 is downstream of the pRB-E2F pathway, essential for proliferation and amplified in cancer. The EMBO Journal, 22, 5323–5335.

Obier, N., & Muller, A. M. (2010). Chromatin flow cytometry identifies changes in epigenetic cell states. Cells, Tissues, Organs, 191, 167–174.

Marks, H., Chow, J. C., Denissov, S., et al. (2009). High-resolution analysis of epigenetic changes associated with X inactivation. Genome Research, 19, 1361–1373.

Whyte, W. A., Orlando, D. A., Hnisz, D., et al. (2013). Master transcription factors and mediator establish super-enhancers at key cell identity genes. Cell, 153, 307–319.

Langmead, B., Trapnell, C., Pop, M., & Salzberg, S. L. (2009). Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biology, 10, R25.

Zhang, Y., Liu, T., Meyer, C. A., et al. (2008). Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biology, 9, R137.

Heinz, S., Benner, C., Spann, N., et al. (2010). Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Molecular Cell, 38, 576–589.

Quinlan, A. R., & Hall, I. M. (2010). BEDTools: a flexible suite of utilities for comparing genomic features. Bioinformatics, 26, 841–842.

Saldanha, A. J. (2004). Java Treeview–extensible visualization of microarray data. Bioinformatics, 20, 3246–3248.

Desbaillets, I., Ziegler, U., Groscurth, P., & Gassmann, M. (2000). Embryoid bodies: an in vitro model of mouse embryogenesis. Experimental Physiology, 85, 645–651.

Som, A., Harder, C., Greber, B., et al. (2010). The PluriNetWork: an electronic representation of the network underlying pluripotency in mouse, and its applications. PLoS One, 5, e15165.

Choi, D., Lee, H. J., Jee, S., et al. (2005). In vitro differentiation of mouse embryonic stem cells: enrichment of endodermal cells in the embryoid body. Stem Cells, 23, 817–827.

Fenouil, R., Cauchy, P., Koch, F., et al. (2012). CpG islands and GC content dictate nucleosome depletion in a transcription-independent manner at mammalian promoters. Genome Research, 22, 2399–2408.

Radzisheuskaya, A., Le Bin Chia, G., Dos Santos, R. L., et al. (2013). A defined Oct4 level governs cell state transitions of pluripotency entry and differentiation into all embryonic lineages. Nature Cell Biology, 15, 579–590.

Kaneko, S., Son, J., Shen, S. S., Reinberg, D., & Bonasio, R. (2013). PRC2 binds active promoters and contacts nascent RNAs in embryonic stem cells. Nature Structural and Molecular Biology, 20, 1258–1264.

Kim, H., Jang, M. J., Kang, M. J., & Han, Y. M. (2011). Epigenetic signatures and temporal expression of lineage-specific genes in hESCs during differentiation to hepatocytes in vitro. Human Molecular Genetics, 20, 401–412.

Barrand, S., & Collas, P. (2010). Chromatin states of core pluripotency-associated genes in pluripotent, multipotent and differentiated cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications, 391, 762–767.

Hawkins, R. D., Hon, G. C., Lee, L. K., et al. (2010). Distinct epigenomic landscapes of pluripotent and lineage-committed human cells. Cell Stem Cell, 6, 479–491.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. A. Wutz for providing Eed KO ESCs, Heike Wecklein for excellent technical assistance, Jessica Schmitt for helping with pictures, Kristian Helin’s lab for the pCMVHA EED wt plasmid (Addgene). This work was supported by the DFG-funded GRK 1048 (AM) and SPP1356: Pluripotency and cellular reprogramming (AM, MZ). This work was supported in part by the Graduate School of Life Sciences, University of Würzburg.

Author contribution

NO, VH performed experiments; NO, MB, AM designed experiments, analyzed data, wrote paper; NO, QL, MZ and PC performed microarray and bioinformatic analyses.

Author Information

The microarray data sets are available from the GEO (Gene Expression Omnibus) website under accession number GSE49305.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no potential conflicts of interest.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(XLSX 60 kb)

Fig. S1

Analysis of EZH2 and H3K27me3 levels and apoptosis in Eed KO ESCs. (A) Representative Western blot analysis for expression of EZH2 and H3K27me3. (B) One million WT and Eed KO ESCs were seeded in ESC culture conditions and counted after 2 days. n=3 (C) Frequencies of apoptotic cells in ESC cultures and in day 3 and day 7 EBs. n=3 (D) Frequency of EB forming cells in Eed KO and WT ESC cultures. Single cell suspensions were prepared and graded numbers of cells were seeded into hanging drop cultures. Drops that developed no EBs 2 weeks post seeding were scored as negative and fractions of negative drops were plotted against seeded cell numbers. n = 3. Regression curves were calculated and the function was used to calculate the frequency of EB forming cells. (JPEG 3186 kb)

Fig. S2

Validation of microarray expression data via qRT PCR analysis. (A) Shown are qRT PCR results for Oct4, Sox2, Nanog, Eed, Ezh2 and Ehmt2 in WT and Eed KO ESCs or d3 and d7 EB cells. n=3 (B) Expression values of the same genes as in (A) as obtained from microarray analysis. (JPEG 4217 kb)

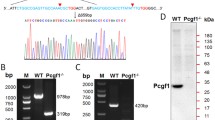

Fig. S3

Overexpression of a WT Eed transgene in Eed KO ESCs partially rescues the KO phenotype. (A) Western blot analysis for expression of EED and H3K27me3. Eed KO ESCs (J1) were transiently transfected with a CMV-driven Eed expression plasmid. Protein extracts from mock-, empty vector- or Eed vector-transfected cells were harvested and analyzed 1 and 3 days post transfection. Wildtype ESCs (R1) or MEF are shown. (B) qRT PCR for expression of core pluripotency genes at 1, 3, or 7 days of EB differentiation. (C) Representative micrographs of mock-transfected WT ESCs (J1), of empty vector-transfected or wildtype EED vector transfected Eed KO ESCs (J1) at day 3 and day 7 of differentiation are shown. A-C: n=2. (JPEG 8278 kb)

Fig. S4

Knockdown of Oct4 in Eed KO ESCs does not rescue the KO phenotype. (A) qRT PCR analysis of Oct4, Nanog and Sox2 expression in WT (J1), scr siRNA- or Oct4 siRNA-transfected Eed KO ESCs (J1). ESCs were differentiated for 1, 3 or 7 days. RNAs were harvested and qRT PCRs were performed. (B) Representative micrographs of mock-transfected WT, scr or Oct4 siRNA transfected Eed KO ESCs at day 3 and day 7 of differentiation are shown. A, B: n=4. (JPEG 8038 kb)

Fig. S5

Correlation of H3K27me3 and gene expression changes and box-whiskers-plots of wildtype and EZH2 KO ESC expression changes. (A) Shown are global H3K27me3 intensity plots at promoter regions (+/− 1,5 kb TSS) of all genes ranked on highest to lowest H3K27me3 values (left). Aligned are gene expression differences between day 7 differentiated and undifferentiated WT (middle) and KO ESCs (right). Color codes are indicated at bottom of diagrams. (B) Previously published microarray data of Ezh2 KO ESCs (d0) or d6 EB cells [10] were used to extract gene expression values of 158 PRC2-dependent genes (as defined in Fig. 4b). Expression values are shown as box plots. (JPEG 4684 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Obier, N., Lin, Q., Cauchy, P. et al. Polycomb Protein EED is Required for Silencing of Pluripotency Genes upon ESC Differentiation. Stem Cell Rev and Rep 11, 50–61 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12015-014-9550-z

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12015-014-9550-z