Abstract

Background

For patients with sacral tumors, who are well enough for surgery, en bloc resection is the preferred treatment. Survival, postoperative complications, and recurrent rates have been described, but patient-reported outcomes often are not included in these studies.

Questions/purposes

The purposes of this study were (1) to compare patient-reported outcomes after en bloc sacrectomy, based on the level of sacral nerve root resection, in terms of mental health, physical health, bowel function, and sexual function; and (2) to assess differences in terms of mental health, physical health, and pain between patients with and without a colostomy.

Methods

A total of 74 patients, of whom 58 (78%) were diagnosed with chordoma, were surveyed between February 2012 and October 2014. This represented 48% of patients with sacral chordoma who were alive and who had been treated with a transverse sacral resection between June 2000 and August 2013 at three institutions with a minimum followup of 6 months (mean, 59 months; range, 6–255 months). We chose 6 months because we believe that neurologic deficits generally are stable by this point and that patients generally have recovered from the operation by this time. Patients were divided into five groups based on the most caudal nerve root spared: L5 (N = 10), S1 (N = 22), S2 (N = 17), S3 (N = 18), and S4 (N = 7). Only postoperative outcomes were collected using the National institute of Health’s Patient Reported Measurement Information System (PROMIS) Global Health survey, PROMIS Pain Interference survey, PROMIS Pain Intensity survey, PROMIS Sexual Function survey, and the Modified Obstruction and Defecation Score survey.

Results

Differences between two adjacent levels were found in terms of mental health, physical health, and sexual function. Patients in whom the S2 nerve roots were spared had a lower mental health score (median = 44, interquartile range [IQR] = 41–51) than patients in whom the S3 nerve roots were spared (median = 53, IQR = 48–56, q = 0.049). Patients in whom the S2 nerve roots were spared had a slightly lower physical health score (median = 42, IQR = 40–51) than patients in whom the S3 nerve roots were spared (median = 47, IQR = 45–54, q = 0.043). Patients in whom the S1 roots were spared (median = 1.0, range = 1.0–1.0) had a lower orgasm score than patients in whom the S2 nerve roots were spared (median = 3, range = 2–5, q = 0.027). No differences in terms of mental health, physical health, or pain were found between the colostomy group and the no colostomy group.

Conclusions

The combination of our findings can be used to further educate patients and discuss expectations. In an operative setting, these data can be considered when deciding to place a colostomy.

Level of Evidence

Level III, therapeutic study.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Surgical resection is an important component of the management of primary malignant tumors of the sacrum. Sacrectomy often involves transection of the sacral nerve roots, which can lead to multiple dysfunctions including lower extremity, bowel, bladder, and sexual function [8–11, 13, 14, 16, 19, 21–24]. These effects have been studied from a physiological point of view. For example, quantitative changes in bowel and bladder function using manometry and cystometry have been reported [8, 20]. Other studies based their results on a retrospective review of pre- and postoperative medical records and use dichotomous outcomes [19, 25].

Most studies focus on the crucial oncological outcomes but only briefly address the results of, often objective, functional outcome measures [13, 14, 23]. Patient-reported outcomes are becoming increasingly important in the determination of treatment success. In many fields of medicine, including the field of spine surgery [15], research is focusing increasingly on patient-reported outcomes and the adequacy of questionnaires for specific patient populations. Such outcomes are important because they are unfiltered by the treating physician and allow for a quantitative assessment of qualitative data of the patient’s mental and physical health [17]. In the sacral tumor population, very few efforts have been made to assess the patient-reported outcomes before and after treatment. Qualitative data on quality of life have been assessed through a series of interviews making valid comparison increasingly difficult [2]. Patient-reported outcomes could be used to conceive a more comprehensive, thorough, and comprehensible explanation to the patient.

In a preliminary study [20], we published the data on some of the patients we report here using the same validated patient-reported outcomes tools. This study also includes the data of two additional institutes, more than doubling the original sample size. The small sample size and the concomitant lack of statistical power were major limitations of the preliminary study. The current study considers also the level of nerve root resection as opposed to the level of osteotomy. The level of the bony cut does not always correspond to the level of the nerve root resection. It is possible that, depending on tumor involvement, the nerve roots are sacrificed unilaterally rather than bilaterally as the bony cut would suggest. Similarly, tumor can be involved at a more distal part of the nerve root, which would allow for a more distal bony resection but resection of a more cephalad nerve root. It is known that unilaterally preservation of the nerve root allows for adequate neurological function [25] and it is therefore important to consider the specific nerve roots that are resected to assess neurological outcomes as a function of level of resection.

In addition, at this time there is no consensus on when a colostomy should be used for patients who undergo a high sacral resection and the decision is mainly based on the surgeons’ experience. Patient-reported outcomes from both patients with and without a colostomy could be of value when making this decision.

This study aims to assess differences in patient-reported outcomes after en bloc sacral resection in terms of mental health, physical health, pain intensity, pain interference, sexual function, and bowel function based on level of nerve root resection. Second, we aim to assess differences among mental health, physical health, and pain between patients with and without a colostomy.

Patients and Methods

After a waiver of consent was obtained from each hospital’s institutional review board (institutional review board No. 2013P000057), a triinstitutional effort was made to retrospectively evaluate a longitudinally maintained database containing physical and mental outcome data on patients who underwent en bloc sacral resection resulting from a tumor. At our institution, patient-reported outcome data are collected for all patients who visit the orthopaedic oncology service in the Orthopaedic Oncology Database (institutional review board No. 2013P002411).

Surveys were collected from patients between February 2012 and October 2014. These patients underwent transverse sacral resections between June 2000 and August 2013; patients who underwent a hemipelvectomy or hemisacrectomy were excluded. Primary and recurrent tumors were included. In the sacral chordoma population, recurrent disease is very common [24] and therefore important to include when assessing quality of life. Of the 74 respondents, nine were diagnosed as adenocarcinoma (12%), three a giant cell tumor (4%), three as chondrosarcoma (4%), and two as osteosarcoma (3%). Fifty-eight (78%) respondents were diagnosed as chordoma. This represented 39% (58 of 149) of patients with sacral chordoma who underwent transverse sacral resections during that time period. Twenty-seven (18%) of the patients operated on between June 2000 and August 2013 had died and were not included in this study. Thirty-eight (31%) of the 122 alive patients were not seen in the clinic between February 2012 and October 2014 either because they were on a different followup schedule or they had sent images directly to the treating surgeon for review and were not seen in the clinic. Twenty patients (16%) were seen in the clinic but did not complete a survey because they either opted out or were missed during screening. Six (5%) patients had less than 6 months of followup or did not complete all of the primary outcome measures. Patients who expected to regain their bowel and bladder function and their ability to ambulate independently will often do so within 6 months postoperatively [4, 13] and are expected to remain stable or change unsubstantial after this time interval. The median time between resection and survey completion was 59 months (range, 6–255 months). The goal of the resection for each tumor type is to obtain negative margins. Usually this is achieved through a 1-cm bony cut above the tumor with or without adjuvant radiotherapy. Nerve root resection is dictated by the tumor location. This approach has not changed substantially during the study period.

Patients

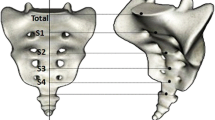

A total of 74 patients, 51 (69%) men and 23 (31%) women, were identified when combining all three institutes. The median age was 62 years (range, 13–80 years) and the median time between surgery and survey completion was 52 months (interquartile range [IQR], 20–74). Patients were divided into five groups based on the most caudal nerve root spared: L5 (N = 10), S1 (N = 22), S2 (N = 17), S3 (N =18), and S4 (N = 7) (Table 1). All 33 patients (46%) of the preliminary study [22] were used in this study, although the distribution among the study groups is different because of the different study group inclusion criteria (that is, level of bony cut versus nerve roots spared). The operation reports were reviewed retrospectively to identify which nerve roots were resected. In five cases, there was a difference of one nerve root between both sides; in one case, the difference was two nerve roots. These patients were treated like the unilateral spared nerve root was spared bilaterally. This decision was based on findings in previous studies that revealed unilateral preservation of nerve roots does not affect overall clinical function [25]. Median tumor volume was 87 cm3 (IQR = 34–231), although data were missing for 10 patients (14%). Radiotherapy was part of the treatment for 48 (65%) of the patients and chemotherapy for 19 (25%) of the patients. At the time of survey completion, 25 (34%) of the patients had a colostomy. Before the survey completion, 20 (27%) patients had a recurrence. A total of 25 patients (34%) had a colostomy at the time of survey completion. Patient with distal sacrectomies are rarely treated with a colostomy; therefore, we excluded the more distal sacrectomies (ie, the S3 and S4 groups) from the colostomy versus no colostomy comparison. All data from the patients undergoing high sacrectomy (ie, L5, S1, and S2) were pooled and divided into two groups based on the presence of a colostomy at the time of survey completion; ie, colostomy (N = 18) and no colostomy (N = 28).

Outcome Variables

The survey is based on recommendations of the Sacral Tumor Study Group (STSG). The STSG consists of clinicians who, during their career, developed a specific interest for tumors of the sacrum and pelvis. The STSG is made up of orthopaedic oncologists who convene each year to discuss advances in the management of sacral tumors. The annual meeting includes a multidisciplinary group that includes orthopaedic oncologists, radiation oncologists, medical oncologists, urologists, gynecologists, and a physiatrist. The questionnaires used in this survey are based on a consensus that was made during the meeting in 2012 held at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, USA. All of the surveys are self-administered by the patient. The survey used for this study incorporates mainly questionnaires from the National Institutes of Health Patient Reported Outcome Measurement Information System (PROMIS). The PROMIS questionnaires used are the Global Item Short Form, which is divided into a mental health and a physical health domain (N = 74) [12], Pain Intensity Short Form 3a (N = 71), Pain Interference Short Form 6b (N = 71) [1], and the Sexual Function Profile v1.0–Male & Female (N = 70) [3]. The Global Short Form is composed of two domains, ie, mental health (N = 74) and physical health (N = 74). The Sexual Function Profile v1.0–Male & Female is divided into six domains: satisfaction (N = 20), interest (N = 70), erection (N = 21), lubrication (N = 5), vaginal discomfort (N = 5), and orgasm (N = 35). All but the interest domain have “Have not tried to…in the last 30 days” as one of the options. This particular answer selection renders the domain unable to calculate a score. The only non-PROMIS questionnaire was the Modified Obstruction-Defecation Score (MODS) (N = 49) [18].

In the case that a patient completed the survey more than once, the most recent one was used for analyses. No preoperative data were collected for these patients. The surveys were collected during clinic visits in the postoperative period using a tablet computer and data were collected through REDCap (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, TN, USA) and Assessment Centre (https://www.assessmentcenter.net) [6] was used for patients who were contacted by mail. REDCap and Assessment Centre are online data collection tools that enable researchers to create study-specific surveys to capture participant data securely online.

PROMIS questionnaires were scored and converted to T-scores using publically available scoring manuals. Missing scores were handled as per PROMIS guidelines, which differ per questionnaire. A higher T-score indicates more of the metric that is being measured, ie, a higher pain interference score means more pain interference. PROMIS T-scores are normalized and calibrated to the general US population [17]. This allows for a comparison of collected data to the mean score of the general US population, which is normalized to a T-score of 50 with a SD of 10. No T-score is available for the orgasm domain, and therefore a comparison to the general US population is not possible. Instead, a raw score is calculated by summing the scores of the domain. Similarly, the MODS is scored by summing the score of all eight items. To enhance the interpretability of patient-reported outcomes, it is important to know what difference is large enough to have an impact on the patients’ treatment or care [26]. This is determined by the minimal clinically importance difference (MCID). Large studies are needed to determine the MCID; unfortunately, these have not yet been done for these specific tools.

Statistics

Continuous variables are reported as median with IQR and categorical variables as frequencies with percentages. For comparison between two groups, the Mann-Whitney U test was used. A difference was declared significant if p < 0.05. We performed the Kruskal-Wallis test to detect differences between more than two groups. If a difference was detected, a multiple pairwise comparison was performed using the Dunn’s test controlling the false discovery rate using the Benjamin-Hochberg method. We accepted a false discovery rate of 10%, which translates to a pairwise comparison being significant when q < 0.10. This method ensured no overanalyzing of the data. Recent research suggests that correcting for false discovery rates is a more powerful method of controlling for multiple comparisons and provides a solid base for drawing conclusions about statistical significance [7]. The reason false discovery rate control is an attractive alternative is that it explicitly controls the error rate of test conclusions among significant results. The exact sign test was used to compare the median score of each group with the standardized mean score of the general US population. All methods of statistical analyses were discussed with the triage lead statistician of the Biostatistical Consulting Program at our institution. The Biostatistical Consulting Program, funded by the National Institutes of Health, supports investigators at our institution undertaking clinical and translational research. We used Stata 13.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) for all statistical analysis. For the colostomy versus no colostomy comparison, a post hoc power analysis with alpha set on 0.05 was done to determine achieved power in terms of metal health (power: 0.05, delta: 0.60), physical health (power: 0.16, delta: 2.3), and pain interference (power: 0.05, delta: 0.30). To achieve a power of 0.80, assuming a similar delta and variability, we would have needed large sample sizes to detect differences in mental health (7792 patients), physical health (328 patients), and in pain interference (18,155 patients). With the current sample size we would have found a difference when the delta would have exceeded 8.3 for mental health, 6.5 for physical health, and 8.3 for pain interference.

Results

Comparison of Study Cohort With the Complete Sacral Chordoma Cohort

We compared demographic data from our study cohort with all sacral chordoma patients from the three institutions combined. No differences were found in terms of age in years (total: 57, SD: ± 15; study: 57, SD: ± 16; p = 0.888), sex (total male: 68%; study male: 72%; p = 0.999), or tumor volume in milliliters (total: 511, SD: ± 1307; study: 380, SD: ± 829; p = 0.416).

Mental and Physical Health as a Function of Root Level

Our primary outcomes measures were the mental health and physical health domains of the PROMIS Global questionnaire. Patients in whom the S2 roots were spared exhibited the lowest mental health score (median = 44, IQR = 41–51) and patients in whom the S4 nerve roots were spared had the highest mental health score (median = 56, IQR = 46–63) (Table 2). Our analyses showed a difference in mental health between the groups (Fig. 1; p = 0.033). A pairwise subgroup comparison showed that patients in whom no sacral nerve roots were spared had a lower mental health score (median = 46, IQR = 39–53) than patients in whom the S3 nerve roots were spared (median = 53, IQR = 48–63, q = 0.094) and than patients in whom the S4 nerve roots were spared (median = 56, IQR = 46–63, q = 0.053). Patients in whom the S1 nerve roots were spared had a lower mental health score (median = 46, IQR = 44–59) than patients in whom the S4 nerve roots were spared (median = 56, IQR = 46–63, q = 0.074). Patients in whom the S2 nerve roots were spared had a lower mental health score (median = 44, IQR = 41–51) than patients in whom the S3 nerve roots were spared (median = 53, IQR = 48–56, q = 0.049) and than patients in whom the S4 nerve roots were spared (median = 56, IQR = 46–63, q = 0.045). None of the groups had a different mental health status compared with the general US population (mean = 50, SD = 10).

PROMIS Global questionnaire. A difference in terms of mental health was detected between two adjacent levels, ie, S2 (median = 46, IQR = 44–59) and the S3 groups (median = 53, IQR = 46–63, q = 0.049). A difference in terms of physical health was detected between two adjacent levels, ie, S2 (median = 45, IQR = 40–51) and the S3 groups (median = 47, IQR = 45–54, q = 0.043). The black diamonds indicate a significant difference compared with the general US population (mean = 50).

Patients in whom nerve roots S1 were spared had the lowest physical health score (median = 42, IQR = 37–48) and patients in whom the nerve roots S4 were spared (median = 54, IQR = 51–62) had the highest physical health scores (Table 2). Our analyses detected a difference between the groups with a tendency for lower physical health in patients with less nerve roots spared (Fig. 2; p = 0.002). A subgroup analysis showed that patients with no sacral nerve roots spared (median = 44, IQR = 37–48) had lower physical health score than the patients in whom the S3 nerve roots were spared (median = 47, IQR = 45–54, q = 0.024) and than patients in whom the S4 nerve roots were spared (median = 54, IQR = 51–62, p = 0.068). Patients in whom the S1 nerve root was spared had a lower physical health score (median = 42, IQR = 37–48) than patients in whom the S3 nerve roots were spared (median = 47, IQR = 45–54, q = 0.0081) and than patients in whom the S4 roots were spared (median = 54, IQR = 51–62, q = 0.0045). Patient in whom the S2 nerve roots were spared had lower physical health score (median = 42, IQR = 40–51) than patients in whom the S3 nerve roots were spared (median = 47, IQR = 45–54, q = 0.043) and than patients in whom the S4 nerve roots where spared (median = 54, IQR = 51–62, q = 0.0095). Compared with the general US population (mean = 50, SD = 10), patients with no nerve roots spared had a lower physical health score (median = 44, IQR = 37–48, p = 0.002) and so did patients in whom the S2 nerve roots were spared (median = 42, IQR = 37–48, p = 0.004).

Pain Scores as a Function of Root Level

No effect was detected between the groups in terms of pain interference scores (Fig. 2; p = 0.653) or pain intensity scores (Fig. 2; p = 0.286). There were differences detected between our patient sample and the general US population (mean = 50, SD = 10); patients in whom no nerve roots were spared had a higher pain interference score (median 58, IQR = 56–59, p = 0.022); so did the patients in whom the S1 nerve roots were spared (median = 60, IQR = 53–63, p = 0.031) and the patients in whom the S3 nerve roots were spared also had a higher pain interference score (median = 55, IQR = 53–59, p < 0.001). Patients in whom the S3 nerve roots were spared had a lower pain intensity score (median = 45, IQR = 41–49, p = 0.012), than the score of the general US population (mean = 50, SD = 10) (Fig. 2).

Bowel and Sexual Function Score as Function of Root Level

No differences were found between the groups for the obstruction/defecation score (p = 0.142). No difference between the groups was found in the sexual function score (Fig. 3) in terms of satisfaction (p = 0.772), interest (p = 0.874), lubrication (p = 0.814), vaginal discomfort (p = 0.639), or erectile function (p = 0.091). In terms of erectile function, a difference was found (p = 0.033). Patients in whom the S1 roots were spared had the lowest orgasm score (median = 1.0, range = 1.0–1.0); the highest score was found in patients in whom the S4 were spared (median = 4, range = 2–5). A subgroup analysis showed that patients in whom the S1 roots were spared (median = 1.0, range = 1.0–1.0) had a lower orgasm score than patients in whom the S2 nerve roots were spared (median = 3, range = 2–5, q = 0.027) and than patients in whom the S4 nerve roots were spared (median = 4, range = 2–5, q = 0.018) (Fig. 3).

Patients With and Without Colostomies

With the numbers available, we detected no difference in terms of mental health, physical health, or pain interference (Table 3); however, as earlier noted, the statistical power on these comparisons was quite low. Both groups did display worse physical health (colostomy: median = 41, IQR = 37–45, p < 0.001; no colostomy: median = 42, IQR = 39–49, p = 0.013) and more pain interference (colostomy: median = 59, IQR = 53–62, p = 0.049; no colostomy: median = 57, IQR = 49–64, p = 0.019) compared with the US general population (mean = 50, SD = 10).

Discussion

Consensus within contemporary medicine dictates the treatment of sacral tumors with radical en bloc resection as the standard of care for optimal local control [21, 24]. En bloc sacral resection often entails resecting nerve roots, which can have a great impact on a patient’s quality of life. Based on the level of resection, the sacrifices differ and therefore presumably also the impact on the quality of life. Currently, there is a paucity of studies reporting on patient-reported outcomes after treatment for sacral tumors. Studies that do address these outcomes use different tools and use tools that are not completed by the patient, making institutional comparisons increasingly difficult [13, 14, 19, 23, 25]. We found that, when comparing patient-reported outcomes based on the sacral nerve roots that were sacrificed, mental and physical health decreased when S3 was bilaterally sacrificed. We also found a decrease in the ability of having an orgasm when S2 was bilaterally sacrificed. Among patients with a high sacrectomy, no differences were found between patients with and without a colostomy in terms of mental health, physical health, and pain interference.

This study has several limitations. First, we were not able to survey all eligible patients for several reasons. The main reason was that patients were not seen in the clinic during the study period; this does not directly imply anything about the health status of these patients. It could be that patients were on a different followup schedule or followup could suffice with a review of images sent to the provider. These factors are mostly dependent on their preference rather than health status. We were able to survey 48% of the patients with sacral chordoma from the three institutions combined. To test whether this was a representative sample, we compared demographic data from our sample with all sacral chordoma patients and found no differences in terms of age, sex, or tumor volume. Second, we did not collect data on preoperative mental health, physical health, pain, sexual function, and bowel function as reported by the patient. Thus, the comparison of the actual consequences of sacral tumor surgery on patient quality of life is difficult, if not impossible, to measure. For example, some patients could have presented a poor quality of life before surgery, resulting in a false score of quality of life measured solely postoperatively. Furthermore, it could also be possible that the patient had a high preoperative quality of life in which case a similar operation could have an even bigger impact. Although assuming that these differences exist within every group, comparison between the groups is a valid method. A retrospective study of patient medical charts could have provided preoperative insight regarding health status; however, qualitative data are unreliable when not reported by the person of interest.

Another limitation was that our patients did not complete the survey at a uniform followup time. Patients’ health status could still change after the 6 months of minimum followup used for this study. The 6-month time interval was based on previous studies showing that most of the patients regained good ambulatory, bowel function, and bladder function after 6 months [4, 13]. We chose 6 months because we believe that neurological deficits generally are stable by this point and that patients generally have recovered from the operation by this time. The potential confounding effect should be minimal considering our mean of 59 months of followup. We compared the mental and physical health scores of patients undergoing high sacrectomy with less than 1 year of followup (six patients, median mental health: 40.0; IQR: 39–46 and median physical health: 37.4; IQR: 37–37) to high sacrectomy patients with more than 2 years of followup (30 patients, median mental health: 45.8; IQR: 41–56; p = 0.088 and median physical health: 42.3; IQR: 40–18; p = 0.162) and found no differences. An additional limitation was that the questionnaires we used did not cover some aspects specifically, bladder function for example. We are currently collecting qualitative data on what patients and experts think are important aspects that should be addressed in a quality of life survey. Also, not all patients completed all the questions of all the questionnaires; therefore, some scores could not be calculated. Although, these numbers were small for the pain interference score (four incomplete scores, 5%) and pain intensity score (four incomplete score, 5%), they were bigger for the MODS score (25 missing, 34%), and substantially decreased the sample size making the analysis less powerful. Finally, probably not all statistically significant differences are clinically important. Small differences like the 5-point difference in physical function score between patients in whom the S2 nerve roots were spared and patients in whom the S3 was nerve roots were spared might not reach the minimal clinically important difference threshold.

Our primary outcome measure was the PROMIS Global Health score. This questionnaire allows for the calculation of a mental health and a physical health domain. We found a difference in mental health based on the level of nerve root resection. Because we did not dichotomize our groups into high and low sacral resection, a difference between the L5 group and the S4 group seems an obvious result. A relative big decrease in mental health between the S2 and the S3 groups was also observed. This translates to a decrease in mental health when the S3 nerve roots are sacrificed. Unfortunately there are no MCID values to determine whether this difference is clinically important, although we suspect a difference of this size (Fig. 1) would be clinically important. Similar results were found for the physical health score, in which not only nonsubsequent groups exhibited differences; comparisons between the S2 group and S3 group also presented deviations, although somewhat smaller as compared with the mental health score. These results suggest that sacrificing the S3 nerve roots would decrease the patients’ physical health. A recent study, using the same questionnaire, showed comparable results for physical health, but not for mental health [22]. Several studies done from a physiological point of view show that the sparing of S3 is necessary for normal function of bowel, bladder function, and sexual function [5, 8, 9, 11, 25]. This might explain the impact on physical and mental health when S3 is sacrificed. It does not explain why we found no difference between the L5 and S1 groups, because preservation of the S1 nerve root is essential in maintaining lower extremity function. This might be explained by the concept that patient-reported outcomes will always be a perception of the patient; so, for example, “usual activities” in a question concerning physical function could mean something very different for someone who lost the ability to ambulate years ago than to someone who is still trying to ambulate as much as their function allows them to.

To measure pain, we used the PROMIS pain interference and the pain intensity [1], assessing the consequences of pain on relevant aspects of one’s life and how much a person hurts, respectively. Pain has not often been described in previous studies, but our results show that the groups with less nerve roots spared (ie, L5, S1, and S2) incurred more consequences of the pain on relevant aspects of their life as compared with the general US population. We did not find a difference between our study groups and the general US population in terms of how much a patient hurts (pain intensity score), except for the S3 group; they reported less pain than the general US population. The pain intensity consists of three questions about the patients’ average and worst pain in the last 7 days and their current level of pain. An explanation for the lack of difference could be the fairly long mean followup (52 months) in this study. Probably, because these patients are educated preoperatively and have lived with pain for years, they have developed a different perception of pain compared with the general US population. This would explain why we do see a decrease in pain intensity scores to even a better score than the general US population. Interestingly, the pain interference score does differ for the higher resection levels; this could mean patients do not experience the pain as intense any more but more as bothersome in their daily life. We did not analyze the questionnaires’ appropriateness for this specific patient population, but it seems as if the pain interference questionnaires included more relevant questions for this patient group.

The sexual function questionnaire has six domains, of which five have an option to opt out by selecting lack of sexual intercourse within the last month. This left us with few responses per domain, especially for the female-specific domains. This option was chosen less as more nerve roots were spared. Possibly, patients with worse sexual function found these questions too confronting and chose to opt out. Not all groups had the same ability to achieve an orgasm. Earlier studies showed that preservation of S2 is necessary to preserve the ability to achieve an orgasm [5, 10]. This supports our results that showed that the ability to have an orgasm decreased when S2 was sacrificed. Although the orgasm score is not standardized and therefore cannot be compared with the general US population, it is still valid to compare the raw scores between study groups.

The questionnaire used to assess bowel function (ie, MODS) only addresses defecation and obstruction. Although we saw a decrease in the obstruction complaints as more nerve roots were spared, we did not find a difference because of the large variability within each group. We do not feel that this questionnaire covers all the aspects of bowel function and this will be addressed in the current redevelopment of the sacral tumor questionnaire.

The large sample sizes that are needed to detect a difference given the delta found in our study suggest that there is actually little difference between the colostomy and no colostomy groups.

Our data corroborate previous studies that demonstrate the importance of the S3 nerve root with regard to function. When the S3 nerve roots are to be resected based on the location of the tumor, a preoperative discussion should occur with the patient about the potential effects on physical and mental function. At the very least one can have discussions about ways in which to cope with the expected stress placed on the patient’s physical and mental function. Because pain is one of the things that patients with cancer are naturally concerned about, the data presented here should be incorporated into a preoperative discussion. Patients who will undergo a lower sacrectomy can be counseled that pain is not typically a long-term consequence of their surgery. Patients who will undergo a higher sacrectomy are more likely to have pain that interferes with their life. These patients may benefit from preoperative discussions about coping mechanisms and perhaps could see a clinician trained in the psychology of pain and pain management before surgery. Furthermore, the data presented here could be the basis of further discussions with pain clinicians regarding future strategies to help mitigate pain; for instance, the placement of intrathecal pain pumps outside of the surgical field as an example. Our data also show that the use of colostomy may not improve overall quality of life, although with a limited sample. Clearly there are some advantages to colostomy such as decreased soilage of surgical incisions. However, most patient seem to adjust and overall quality of life may not be affected by the use of colostomy.

References

Amtmann D, Cook KF, Jensen MP, Chen WH, Choi S, Revicki D, Cella D, Rothrock N, Keefe F, Callahan L, Lai JS. Development of a PROMIS item bank to measure pain interference. Pain. 2010;150:173–182.

Davidge KM, Eskicioglu C, Lipa J, Ferguson P, Swallow CJ, Wright FC. Qualitative assessment of patient experiences following sacrectomy. J Surg Oncol. 2010;101:447–450.

Flynn KE, Jeffery DD, Keefe FJ, Porter LS, Shelby RA, Fawzy MR, Gosselin TK, Reeve BB, Weinfurt KP. Sexual functioning along the cancer continuum: focus group results from the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®). Psychooncology. 2011;20:378–386.

Fourney DR, Rhines LD, Hentschel SJ, Skibber JM, Wolinsky JP, Weber KL, Suki D, Gallia GL, Garonzik I, Gokaslan ZL. En bloc resection of primary sacral tumors: classification of surgical approaches and outcome. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;3:111–122.

Fujimura Y, Maruiwa H, Takahata T, Toyama Y. Neurological evaluation after radical resection of sacral neoplasms. Paraplegia. 1994;32:396–406.

Gershon R, Rothrock NE, Hanrahan RT, Jansky LJ, Harniss M, Riley W. The development of a clinical outcomes survey research application: Assessment Center. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:677–685.

Glickman ME, Rao SR, Schultz MR. False discovery rate control is a recommended alternative to Bonferroni-type adjustments in health studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:850–857.

Gunterberg B, Kewenter J, Petersen I, Stener B. Anorectal function after major resections of the sacrum with bilateral or unilateral sacrifice of sacral nerves. Br J Surg. 1976;63:546–554.

Gunterberg B, Norlen L, Stener B, Sundin T. Neurourologic evaluation after resection of the sacrum. Invest Urol. 1975;13:183–188.

Gunterberg B, Petersen I. Sexual function after major resections of the sacrum with bilateral or unilateral sacrifice of sacral nerves. Fertil Steril. 1976;27:1146–1153.

Guo Y, Palmer JL, Shen L, Kaur G, Willey J, Zhang T, Bruera E, Wolinsky JP, Gokaslan ZL. Bowel and bladder continence, wound healing, and functional outcomes in patients who underwent sacrectomy. J Neurosurg Spine. 2005;3:106–110.

Hays RD, Bjorner JB, Revicki DA, Spritzer KL, Cella D. Development of physical and mental health summary scores from the patient-reported outcomes measurement information system (PROMIS) global items. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:873–880.

Hsieh PC, Xu R, Sciubba DM, McGirt MJ, Nelson C, Witham TF, Wolinksy JP, Gokaslan ZL. Long-term clinical outcomes following en bloc resections for sacral chordomas and chondrosarcomas: a series of twenty consecutive patients. Spine. 2009;34:2233–2239.

Hulen CA, Temple HT, Fox WP, Sama AA, Green BA, Eismont FJ. Oncologic and functional outcome following sacrectomy for sacral chordoma. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88:1532–1539.

Janssen SJ, Teunis T, van Dijk E, Ferrone ML, Shin JH, Hornicek F, Schwab JH. Validation of the Spine Oncology Study Group-Outcomes Questionnaire to assess quality of life in patients with metastatic spine disease. Spine J. 2015 Aug 5 [Epub ahead of print].

Li D, Guo W, Tang X, Ji T, Zhang Y. Surgical classification of different types of en bloc resection for primary malignant sacral tumors. Eur Spine J. 2011;20:2275–2281.

Liu H, Cella D, Gershon R, Shen J, Morales LS, Riley W, Hays RD. Representativeness of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Internet panel. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1169–1178.

Madbouly KM, Abbas KS, Hussein AM. Disappointing long-term outcomes after stapled transanal rectal resection for obstructed defecation. World J Surg. 2010;34:2191–2196.

Moran D, Zadnik PL, Taylor T, Groves ML, Yurter A, Wolinsky JP, Witham TF, Bydon A, Gokaslan ZL, Sciubba DM. Maintenance of bowel, bladder, and motor functions after sacrectomy. Spine J. 2014;15:222–229.

Nakai S, Yoshizawa H, Kobayashi S, Maeda K, Okumura Y. Anorectal and bladder function after sacrifice of the sacral nerves. Spine. 2000;25:2234–2239.

Osaka S, Osaka E, Kojima T, Yoshida Y, Tokuhashi Y. Long-term outcome following surgical treatment of sacral chordoma. J Surg Oncol. 2014;109:184–188.

Phukan R, Herzog T, Boland PJ, Healey J, Rose P, Sim FH, Yazsemski M, Hess K, Osler P, DeLaney TF, Chen YL, Hornicek F, Schwab J. How does the level of sacral resection for primary malignant bone tumors affect physical and mental health, pain, mobility, incontinence, and sexual function? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474:687–696.

Ruggieri P, Angelini A, Ussia G, Montalti M, Mercuri M. Surgical margins and local control in resection of sacral chordomas. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2010;468:2939–2947.

Schwab JH, Healey JH, Rose P, Casas-Ganem J, Boland PJ. The surgical management of sacral chordomas. Spine. 2009;34:2700–2704.

Todd LT Jr, Yaszemski MJ, Currier BL, Fuchs B, Kim CW, Sim FH. Bowel and bladder function after major sacral resection. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2002;397:36–39.

Wyrwich KW, Bullinger M, Aaronson N, Hays RD, Patrick DL, Symonds T, Clinical Significance Consensus Meeting Group. Estimating clinically significant differences in quality of life outcomes. Qual Life Res. 2005;14:285–295.

Acknowledgments

We thank Al Ferreira RN, and Anne Fiore NP, Orthopaedic Oncology Service, Massachusetts General Hospital, for their assistance in working with patients during data collection for this project. We also thank the Harris Center for Chordoma Care at Massachusetts General Hospital. We thank Jesse Galle, Orthopaedic Surgical Service, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, for his assistance with data acquisition and database management.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Two of the authors (PJB, JHH) report that their institution receives partial funding by a grant from the National Cancer Institute/National Institutes of Health (Grant #P30-CA008748).

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research ® editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

This work was performed at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA, USA.

About this article

Cite this article

van Wulfften Palthe, O.D.R., Houdek, M.T., Rose, P.S. et al. How Does the Level of Nerve Root Resection in En Bloc Sacrectomy Influence Patient-Reported Outcomes?. Clin Orthop Relat Res 475, 607–616 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-016-4794-3

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-016-4794-3