Abstract

This study examines how often and why suspects who have reported being either guilty or innocent remain silent, confess, or deny accusations in police interview situations. Convicted offenders under current probation or parole in Germany (N = 280) completed a questionnaire about their perceptions of up to six specific police interview situations they had experienced in their lifetime. As predicted, more suspects reported having confessed truthfully (64.3%) compared to falsely (4.1%) at least once in their lifetime; and more suspects reported having remained silent in guilty interview situations (58.4%) compared to innocent interview situations (18.4%). Unexpectedly, approximately an equal number of suspects reported having denied truthfully (39.8%) and falsely (40.2%) at least once in their lifetime. The main reasons reported for these statement types were that evidence seemed to indicate guilt (true confessions), suspects desired to end the uncomfortable interview situation or protect the real perpetrator/another person (false confessions), evidence seemed weak (false denials), suspects felt innocent (true denials), they desired to protect themselves (silence while being interviewed when guilty), and they followed their attorneys’ advice (silence while being interviewed when innocent). Findings are discussed in the context of the police and psychological research and practice.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

There has been extensive research on the frequencies, reasons, and factors associated with true and especially false confessions (for overviews, see Gudjonsson 2003; Kassin et al. 2010). However, there is very little legal-psychological literature focusing on other statement behavior from the suspects’ perspective. In many countries, suspects can legally decide for themselves whether or not to make a statement (e.g., § 136 German Code of Criminal Procedure). Under German law, if suspects decide to remain silent, interviewers have to end the interview and are not permitted to ask further questions. If suspects decide to make a statement, they can deny or confess to an accusation. Hence, there are, roughly speaking, three possible statement behaviors that suspects can use in police interviews: remaining silent, confessing, and denying. Differentiating for each statement between interviews for a crime committed (interviewed when guilty) or not committed (interviewed when innocent) results in six interview situations. The present self-report study examines the lifetime prevalences (referring to the total number of participants), conditional probabilities (referring to the total number of innocent or guilty interview situations reported by participants), and reasons for remaining silent, confessing, or denying in relation to the suspects’ reported guilt or innocence status.

Approaches in Research on Suspects’ Statement Behavior

Research on suspect interviews may not only highlight and minimize errors and pitfalls (e.g., Kassin et al. 2010) but also identify and provide practical opportunities and solutions (e.g., Meissner 2021). In the past, one particular focus has been on suspects’ confessions (e.g., Gudjonsson 2003, 2018). These studies often applied behavioral observations of police interviews (e.g., Leo 1996; for an overview, see Moston and Engelberg 2011) or analyses of case files (e.g., Cassell and Hayman 1996). Moston and Engelberg (2011) presented general confession rates for the USA, Great Britain, and Australia ranging from 42 to 76%. However, this range of estimates did not refer exclusively to true confessions, and may also include false confessions (i.e., in observational studies, it is rarely possible to measure the objective or reported status of guilt or innocence). Simply put, this line of research lacks information on the guilt or innocence of the suspects.

Acquittals in retrials can be used to gain information on underlying innocence (e.g., Leuschner et al. 2019). Similarly, several studies use well-known databases (e.g., the Innocence Project 2021, or the National Registry of Exonerations 2021) to examine false confessions more closely (e.g., Appleby et al. 2013). However, this approach can provide only little information on the general prevalence of false confessions. Also, it provides no information on the prevalence of and reasons for true confessions, true/false denials, and remaining silent.

A third research approach is to consult interviewees directly via self-reports which has been frequently applied to study false confessions (e.g., Gudjonsson and Sigurdsson 1994). Self-reports have also been used occasionally to examine true confessions, but almost not at all for the other statement behaviors (see below). Naturally, this approach has the typical limitations of survey studies (e.g., social desirability, memory distortions, intentional false statements). However, self-report studies do provide an opportunity to approximate the underlying guilt or innocence (i.e., reported status of being guilty or innocent), to gain insights into frequency distributions of distinct statement behaviors by real-life suspects, and to learn about their subjective reasons for them. This, in turn, complements studies based on experiments, observations, and case files. Therefore, the present study used self-reports of convicted offenders about their police suspect interviews.

True and False Confessions

Table 1 shows that most self-report studies focus on false confessions. The self-reported prevalence of false confessions by inmates/offenders and forensic patients in Iceland, the USA, and Germany varies between 5.9 and 33%. However, not all studies captured the suspects’ reports on whether they had ever been interviewed; and, if so, whether they were guilty or innocent in these interview situations. Therefore, these prevalence estimates refer to the total population of suspects, including those who have never been interviewed (i.e., remained silent) and those who were guilty. However, innocence is a necessary premise for a false confession. That means, calculating the prevalence of false confessions by considering the whole sample might underestimate the actual risk suspects face in interviews (Volbert et al. 2019). Therefore, another way to estimate the risk of false confessions is to calculate the conditional probability by relating the number of false confessions to the number of innocent interview situations. Following this approach and considering only the suspects who were interviewed when innocent and thus had been at risk of committing a false confession, Volbert et al. (2019) found a conditional probability of 25% (compared to a prevalence of 16% for the overall sample). The main reported reasons for false confessions in self-report studies were police/interviewing pressure, protection of another person/the real offender, and avoidance of police detention/hope for mitigation of sentence (e.g., Redlich et al. 2010; Sigurdsson and Gudjonsson 2001; Volbert et al. 2019). False confessions were reported most frequently for property offenses, traffic violations, and violent offenses.

In comparison to false confessions, Table 1 shows that we found only four self-report studies that examined true confessions among inmates, offenders, or forensic patients. These revealed a prevalence ranging between 28 and 92%. Most commonly reported reasons for true confessions were the perceived proof, a need to clear one’s conscience, police pressure, custodial pressure, and the hope of being released from custody (Gudjonsson et al. 2004a, b; Sigurdsson and Gudjonsson 1994; Volbert et al. 2019). Only one self-report study captured the crime types of true confessions, whereby the highest rates were for serious traffic violations and drug offenses (Sigurdsson and Gudjonsson 1994). Taken together, research on false confessions is steadily growing, but very little is known about the frequencies and reasons for true confessions. Furthermore, in addition to classical calculations of prevalence (specific statement behaviors related to the overall sample of participants), the present study also calculates conditional probabilities (specific statement behaviors related to the total number of innocent or guilty interview situations). This should lead to a better understanding of suspects’ considerations and verbal behaviors.

Denials and Being Silent

Overall, only little research has focused on how often and why suspects deny accusations (for exceptions, see Holmberg and Christianson 2002; Moston and Stephenson 2009). Table 1 shows that we found only two studies examining the frequencies of denials by inmates, offenders, or forensic patients: In the first study, the prevalence of true denials among a sample of forensic patients in Germany was 49%; that of false denials, 31% (Volbert et al. 2019). The second study revealed that the prevalence of true denials among prison inmates in Germany was 51% (Gubi-Kelm et al. 2020). A further study examined the reasons for denials through focus groups and semistructured interviews with sexual offenders (Lord and Willmot 2004). It found that the main reasons for denial included lack of insight, threats to self-esteem and self-image, and fear of negative extrinsic consequences. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is no study contrasting the reasons for denial in suspects who were interviewed when they were guilty versus innocent. In other words, self-report studies did not consider the suspects’ reported status of guilt/innocence when examining the reasons for (true and false) denials.

Research on being silent is very sparse. Table 1 shows only one study examining remaining silent from the suspects’ perspective. The prevalence of remaining silent among forensic patients in Germany was 37% for reported guilty interview situations and 9% for reported innocent interview situations (Volbert et al. 2019). We know of no self-report study examining reasons for remaining silent from the suspects’ perspective. Overall, there are only very few self-report studies with offenders addressing how often and why they deny or remain silent as suspects, and no study examining this in a way that compares innocent and guilty suspects.

The Present Study

The present study examines the lifetime prevalence, conditional probabilities, and reasons for all three statement behaviors (confessions, denials, and being silent) from the perspective of suspects in German police interviews. By taking into account the suspects’ reported guilt and innocence status, it allows us to compare the resulting six distinct interview situations. Based on the previous research presented above, we expected that more suspects would report having confessed truly rather than falsely at least once in their lifetime (Hypothesis 1). We also expected that more suspects would report having denied truthfully than falsely at least once in their lifetime (Hypothesis 2). Moreover, we expected that more suspects would report having remained silent while being interviewed when guilty compared to innocent at least once in their lifetime (Hypothesis 3). These prevalence rates relate to the total number of participants. In addition to this focus on lifetime prevalence, we also examined the probabilities of the three different statement behaviors under the condition of being guilty versus innocent in a given interview situation. Specifically, conditional probabilities refer to the total number of innocent or guilty interview situations reported by participants.

For exploratory purposes, we wanted to examine the reasons for the specific statement behaviors. Here, we expected that the main reasons for a false confession would be to protect another person/the real offender and police/interviewing pressure. Concerning true confessions, we expected that the main reason would be the suspects’ perceptions of the given evidence. We did not formulate any further expectations on the other statement behaviors here due to the lack of relevant studies.

Method

Participants

Participants were 280 convicted offenders under current probation or parole (40 females and 238 malesFootnote 1) with a mean age of 38.0 years (SD = 11.5). A total of 96 participants (34.3%) reported more than one offense for which they were currently convicted; 22 participants (7.9%) did not name a crime. The reported offenses underlying current convictions (N = 435) included assault (n = 83; 29.6%), theft (n = 76; 27.1%), violation of narcotics law (n = 67; 23.9%), fraud (n = 64; 22.9%), robbery (n = 46; 16.4%), material damage (n = 27; 9.6%), offenses against personal freedom (n = 14; 5.0%), homicide (n = 10; 3.6%), sexual offenses (n = 9; 3.2%), traffic offenses (n = 9; 3.2%), and other offenses (n = 30; 10.7%). The length of the current custodial sentence ranged from 1 to 300 months (M = 36.9, SD = 33.85, Mdn = 30). Initially, 305 persons participated in this study, but 25 had to be excluded from the analysis because they dropped out while completing the questionnaire; gave contradictory answers; or showed language difficulties, signs of drug intoxication, or cognitive limitations.

Materials

Pilot Study

As outlined above, research on reasons for denying and remaining silent while being interviewed when innocent or guilty is scarce. Therefore, we conducted a pilot study in order to formulate multiple-choice questions for the main study. Specifically, we asked 16 legal, police, and psychological practitioners and researchers the following four questions via an online questionnaire: (a) “Why do guilty suspects remain silent?” (b) “Why do innocent suspects remain silent?” (c) “Why do guilty suspects deny an accusation?” (d) “Why do innocent suspects deny an accusation?” Then, we categorized the participants’ answers. Main reported reasons for remaining silent while interviewed when guilty were incriminating evidence (n = 7), advice of an attorney (n = 7), and unwillingness to cooperate with the police (n = 6), and while interviewed when innocent, advice of an attorney (n = 7), concealment of another offense (n = 5), and unwillingness to cooperate with the police (n = 6). The main reasons for denying in guilty interview situations were concerns about the expected consequences (n = 15) and feelings of guilt or shame (n = 7). No sufficient reasons were reported for denying when interviewed innocently.

Questionnaire

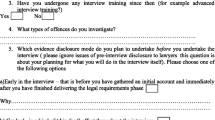

We developed the current questionnaire on the basis of prior research (e.g., Gudjonsson 2003; Houston et al. 2014; Kassin et al. 2010; Redlich et al. 2010) and our pilot study.Footnote 2 It first asked for sociodemographic data (gender, age), followed by the participants’ criminal history (current criminal offense and detention period). Next, participants were asked, “Have the police ever interviewed you as a suspect for an offense you [did/did not] commit?” (yes/no response format). If they affirmed one of these two questions, they were asked follow-up questions about this guilty or innocent interview situation. This procedure was the same for all six interview situations and was structured in four steps: first, participants were asked, “Have you ever [remained silent/confessed/denied an accusation] in a police interview when you were indeed [guilty/innocent]?” (yes/no response format). Second, “How often have you [remained silent/confessed/denied an accusation] when you were indeed [guilty/innocent]?” (open response format). Third, “For which offenses have you been accused when you were interviewed [when guilty/innocent] and [remained silent/confessed/denied an accusation]?” (multiple choice response format). Fourth, “Why did you [remain silent/confess/deny an accusation] when you were interviewed [guilty/innocent]?” (multiple-choice response format except for denying when innocent for which we used an open-ended response format, because the pilot study delivered no information with which to formulate responses; for all given answer options for these multiple-choice questions on the reasons for the statement behaviors, see Table S1 Supplemental Materials).

Procedure

We recruited participants from three judicial social service institutions in Berlin, Germany. Convicted offenders need to attend these regularly for appointments regarding their probation or parole. A research associate addressed and informed them about the study, the voluntariness of their participation, and their anonymity. If they agreed to participate, a research associate explained the questionnaire to them in a waiting area or separate room. The participants then filled out the relevant questions. If they had shown the specific statement behavior at least once in their lifetime (question 1, see above), they were asked to answer the questions about this in more detail (questions 2–4); if not, they were asked to skip these questions and continue with the next interview situation. A research associate was present to answer questions, to read out loud to participants with reading or minor cognitive difficulties, and to collect the completed questionnaires. Completing the questionnaire took approximately 25 min and all participants received 5 euro for their participation. The study was approved by the Berlin Justice Senate’s criminological service.

Statistical Analysis

We tested the hypotheses on lifetime prevalence by analyzing the dichotomous responses to the first question within each of the six sections (i.e., whether the suspect had ever experienced the specific interview situation). In particular, we used a logistic multilevel regression model to predict the responses (yes vs. no) from the (dummy-coded) type of interview situation, with 6 × 280 = 1,680 responses (level 1) nested in 280 participants (level 2). The model included a random intercept that captures individual differences in the propensity to have experienced any of the six interview situations. We then computed the expected (i.e., model implied) lifetime prevalence for each of the six interview situations, and tested the three hypotheses using odds ratios for selected pairwise contrasts.

To examine the probabilities of the three different statement behaviors under the condition of being guilty or innocent, we analyzed responses to the second question within each section (i.e., how often a suspect had experienced the specific interview situation). In a first step, we transformed the data into two long variables representing all reported individual guilty and innocent interview situations respectively. This resulted in 1,922 individual guilty situations (level 1) nested in 268 participants (level 2), and 403 individual innocent situations nested in 144 participants. We then estimated two multinomial multilevel intercept-only models to predict the statement behavior in an individual interview situation (remaining silent vs. confessing vs. denying) separately for guilty and innocent conditions. These models included two random intercepts representing individual differences in the ratio of denying versus remaining silent and the ratio of denying versus confessing. We then computed the expected probabilities for each of the three statement behaviors.

All models were estimated within the statistical platform R 4.0 (R Core Team 2020) using Bayesian estimation with noninformative priors as implemented in the package brms (Bürkner 2017). We employed four Markov chains with 1,000 burnin and 1,000 sampling iterations per chain. Model parameters, expected values, and contrasts, including their 95% credibility intervals, were derived from the posterior predictive distribution, partly with the help of the emmeans package (Lenth 2021).

Finally, we computed the frequencies of offenses (question 3) and reasons for the statement behavior (question 4) separately for the participants who experienced each of the six specific interview situations at least once in their life. The 49 free responses to the open question about the reason for denying while interviewed when innocent were analyzed for content by the second author and combined into categories. However, the answers resulted in only one category being listed more than three times. We named this “I was innocent.” (exemplary answers were “Because I was innocent,” ”Because I did not do it,” “Because I was not involved in the crime,” “Because I had nothing to do with it.”).

Results

Lifetime Prevalence and Conditional Probability of Statement Behaviors

This study captured participants’ perceptions of interview experiences across their entire lives. This made it possible that they were referring to several interviews and also not necessarily to the one for which they were under current probation or parole. The vast majority of participants reported that they had been interviewed when guilty at least once during their lifetime (95.7%, n = 268); and around half of the participants reported that they had been interviewed when innocent (51.4%, n = 144). Some participants indicated that they had been interviewed at least once when both guilty and innocent (47.1%; n = 132), interviewed only when guilty (48.6%; n = 136), or interviewed only when innocent (4.3%; n = 12). The mean number of interviews in a lifetime for guilty interview situations was 6.86 (SD = 7.63), and for innocent interview situations 1.44 (SD = 2.91).

Lifetime prevalence rates based on the logistic multilevel regression model are presented in Fig. 1. Concerning the lifetime prevalence of confessions, 64.3% (95% CI [58.1, 70.1]) of the participants reported at least one true confession, whereas only 4.1% (95% CI [2.3, 6.9]) reported at least one false confession. The corresponding contrast was OR = 42.4 (95% CI [20.1, 75.5]). This was in line with Hypothesis 1. Concerning the lifetime prevalence of denial, 39.8% (95% CI [33.7, 46.0]) of the participants reported at least one true denial, whereas 40.2% (95% CI [34.4, 46.5]) reported at least one false denial. The corresponding contrast was OR = 1.01 (95% CI [0.67, 1.44]). This did not support Hypothesis 2. Finally, 58.4% (95% CI [52.8, 64.8]) of the participants reported having remained silent at least once in their lifetime while interviewed when guilty compared to only 18.4% (95% CI [13.8, 23.6]) while interviewed when innocent. The corresponding contrast was OR = 6.24 (95% CI [4.04, 9.13]). This supported Hypothesis 3. Information on the actual model parameters can be found in the Supplemental Material.

Conditional probabilities based on two separate multinomial multilevel intercept-only models are presented in Fig. 2. In guilty interview situations, the probability of a true confession was 35.8% (95% CI [34.4, 37.2]); that of a false denial, 24.1% (95% CI [22.6, 25.7]); and that for remaining silent, 40.1% (95% CI [38.3, 41.7]). In innocent interview situations, the probability for a false confession was 4.0% (95% CI [2.5, 6.0]), that of a true denial was 60.1% (95% CI [56.6, 63.6]), and that for remaining silent was 35.8% (95% CI [32.6, 39.1]). Again, information on the model parameters can be found in the Supplemental Material.

Types of Offense

Table 2 shows the reported type of offenses for each statement behavior while interviewed when guilty or innocent. Despite the low prevalence of false confessions, participants reported all statement types for almost all crimes. Only traffic offenses were reported exclusively in the context of true confessions.

Reasons for Statement Behaviors

Table 3 shows the most frequently reported reasons for each statement behavior. These were multiple-choice questions except for one question in an open response format (denying while interviewed when innocent). For the full results, see Table S1 in the Supplemental Materials. The main reasons for true confessions were the suspects’ perceptions of the evidence seemed to indicate their guilt. However, frequently reported reasons for true confessions were also the hope of getting a lower sentence and a feeling of guilt. The main reasons for false confessions were to protect another person/the real offender and police/interviewing pressure. Furthermore, the main reasons for false denying were seemingly unclear evidence, and the hope of not being convicted, whereas the only mentioned reason for true denying was that the suspect was innocent. Finally, the main reason for remaining silent in guilty interview situation was that the suspects wanted to protect themselves against misuse of any statement they made. Further frequent reasons were the attorney’s advice to remain silent and the will to find out what evidence the police had before making a statement. The attorney’s advice to remain silent was also the main reported reason for being silent in innocent interview situations.

Discussion

The present study examined the lifetime prevalences, conditional probabilities, and reasons for suspects’ confessions, denials, and remaining silent in police interviews. We will interpret our findings on the three statement behaviors comprehensively and then discuss their scientific and practical implications.

First, as expected, more suspects reported having confessed at least once in their lifetime in guilty interview situations compared to innocent interview situations. The prevalence of false confessions among our sample was 4.1% and slightly below the range between 5.9 and 24% presented in Table 1 for inmates, offenders and forensic patients. However, the corresponding credibility interval in this study includes this range (95% CI [2.3, 6.9]. The false confessions reported here refer to different types of offenses (theft, fraud, assault, robbery, property damage, drug offenses, sexual offenses). The main reported motives for false confessions were to protect the real perpetrator/another person and a desire to end the uncomfortable interview situation. Ending the interview because of an aversive situation can be assigned to the type of coercive false confessions (e.g., Kassin and Wrightsman 1985), and researchers have already given recommendations on how to decrease the risk of this (e.g., Kassin et al. 2010). In contrast, protecting another person belongs to the type of voluntary false confessions (e.g., Kassin and Wrightsman 1985). Whereas this is a frequently reported reason for false confessions, we know of no literature focusing on how interviewers can detect and minimize voluntary false confessions in order to protect another person. This could be a line for future research.

The lifetime prevalence of true confessions in this study (64%) falls in between the wide range of the four self-report studies examining true confessions (28 to 92%; see Table 1). Also, the true confessions reported here refer to different types of offenses, with most being for theft, assault, and drug offenses. The most frequently mentioned reasons for true confessions were that the evidence seemed to indicate guilt and the suspect’s feeling of guilt. This result is in line with a review by Moston and Engelberg (2011) showing that the strength of evidence is a major predictor for a confession, and the meta-analysis by Houston et al. (2014) who found that true confessions were associated with the suspects’ emotional reactions to the interview and their perceptions of the evidence and their guilt. However, suspects also frequently reported the hope to get a lower sentence as a reason for true confessions. This was also a frequently mentioned reason for false confessions. It indicates that suspects consider the perceived consequences when contemplating confessing (on the effect of consequences on confession decisions, see Madon et al. 2012).

Second, as expected, more suspects reported having remained silent at least once in their lifetime in guilty interview situations (58%) compared to innocent interview situations (18%). To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the reasons for being silent in guilty and innocent interview situations from the suspect’s perspective. Here, we want to highlight two results: First, the vast majority of suspects reported having remained silent at least once in their lifetime in guilty interview situations because they wanted to protect themselves against misuse of any statement they made. Furthermore, numerous suspects reported that they remained silent at least once in their lifetime in innocent interview situations because they generally do not make statements to the police. This reflects a rather critical picture of the police, and further research on this needs to follow. Second, the attorney’s advice to remain silent was a frequently reported reason for being silent at least once in a lifetime in both guilty and innocent interview situations. Future research could involve attorneys in order to understand the considerations and decisions of suspects and the interview interactions in more detail.

The lifetime prevalence of false denials (40%) was about the same as that for true denials (40%). This result was unexpected and contradicts the findings by Volbert et al. (2019) indicating a higher prevalence of true denials than false denials among forensic patients. Further research should examine this in more detail. However, both studies show that suspects frequently report true denials. Kassin et al. (2003) have argued that a true denial puts innocent suspects at risk: They found that interviewers tried hardest to obtain a confession when they presumed the suspect’s guilt, but the suspect was in fact innocent. From a suspect’s perspective, being innocent and truly denying an accusation can lead to facing an interviewer aiming to coerce a confession. Coercive and accusatorial interviewing, in turn, raises the risk of false confessions (e.g., Meissner et al. 2014). From the police perspective, “truly denying” is a highly challenging statement behavior. The rationale of this is the cognitive mindset of an interviewer: they may launch a suspect interview when they assume that the suspect is guilty. In this mindset, they may assess denials which do not contain conclusive exculpatory information as a sign of the suspect’s guilt. A pitfall here is that they need to distinguish true from false denials, but the ability of interviewers and humans in general to detect deception is poor (e.g., Bond and DePaulo (2006) found an overall accuracy rate of 54%). Probably the only reliable way to assess the validity of denials is by comparing statements with other evidence (e.g., Vredeveldt et al. 2014), but this becomes impossible if corroborating as well as exculpatory evidence is lacking. Suspects most frequently explained false denying in reported guilty interview situations with seemingly unclear evidence, the hope of not being convicted, and the hope of being released from custody. We believe it is fair to assume that these reasons relate to the strength of the evidence. Taking into account the most frequently reported reason for true confessions (evidence seemingly indicating guilt), this indicates the significant role of evidence from the suspects’ perspective.

This study also shows that the suspects made different statements in police interviews, and specific statement behaviors cannot be attributed solely to innocence or to guilt. Taking the reported guilt or innocence as a starting point, we calculated conditional probabilities that allow descriptions of which types of statements the suspects reported most probably for guilty or innocent interviews. Considering the reported guilty interview situations, the probability was highest for remaining silent (40%), followed by true confessions (36%), and false denial (24%). In contrast, for reported innocent interview situations, the probability was highest for true denial (60%), followed by remaining silent (36%), and eventually false confessions (4%). This finding is highly relevant to investigative practice: First, it shows that suspects—when they make a statement—most commonly make true statements (i.e., true confessions and true denials). Second, from a police perspective, the diversity of statement behaviors in innocent and guilty suspects shows the need to conduct suspect interviews in an open-ended manner. Interviewers’ open-ended mindset is at the core of investigating interviewing and is implemented, for example, in the PEACE model (e.g., Bull 2019). The results of the present study provide support for the international effort to introduce and implement investigative interviewing (e.g., European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment 2019), and generally an open-minded interview approach (Principles on Effective Interviewing for Investigations and Information Gathering 2021).

Finally, for innocent interview situations, the probability that suspects will waive their right to remain silent and deny is higher than that of remaining silent (at least once in their lifetime). In line with experimental findings (Kassin and Norwick 2004), Kassin (2005) has assumed that innocent suspects waive their right to remain silent because they may (a) trust in the fairness of the justice and legal system and expect that their innocence will be believed if they “just tell it like it happened,” and (b) believe that interviewers will be able to read their thoughts and emotions and hence will “see their innocence.” In the present study, the most and exclusive reason for denying in innocent interview situations was the suspects’ explanation “I was innocent.” This underpins Kassin (2005) claim that “innocents put innocence at risk,” because waiving the right to remain silent is an essential antecedent for false confessions. Scherr et al. (2016) also found that suspects’ willingness to waive their rights and deny an offense increased with the strength of their just-world beliefs. However, from a police interviewer’s perspective, the situation is different: Interviewers may conduct suspect interviews when they presume some degree of guilt. Thus, they may assume that the suspect is guilty, assess remaining silent and denying (when no other evidence for cross-checking is available) as an indicator for their guilt, and aim to overcome this and collect confessions. Differently put, remaining silent or denying when being innocent can lead to a risky interview situation with biased perceptions and assessments and coercive interviewing by the police interviewer. This, in turn, can result in false confessions by suspects.

Limitations

This study is based on retrospective self-reports that have some methodological limitations (e.g., social desirability, cognitive biases, remembering specific events out of multiple similar events, estimated frequencies of events), and we had no information with which to validate the participants’ self-reports (e.g., about their status of being guilty or innocent). These limitations hold true when surveying inmates (e.g., Gudjonsson and Sigurdsson 1994) but also police investigators (e.g., Kassin et al. 2007). Nevertheless, suspects are clearly central to suspect interviews, and their perspectives provide crucial information on them. Second, the current nonrepresentative sample limits the generalizability of the results (e.g., all participants were from one German federal state, German-speaking, without extensive cognitive disabilities). Third, the number of false confessions was small, and this limits the precision of the findings on the reasons for confessing when innocent. Future studies should remedy these limitations by including (a) more and a wider range of participants (e.g., persons from different German federal states, non-German speakers, suspects with cognitive disabilities), and (b) more information about the interview context (e.g., duration, location, persons present) and the personal characteristics of the suspects (e.g., mental health).

Conclusion

Overall, this study extends our knowledge on suspects’ reasoning and statement behaviors in police interviews when they are either guilty or innocent. The findings confirm current lines of research from the suspects’ perspective, and they suggest future lines of police and psychological research. For example, the offenders reported that their final statements in the police interviews were diverse and predominantly correct. Considering general research findings (e.g., limited capacity to detect deception and guilt based on nonverbal behaviors), this substantiates the need to conduct suspect interviews in an open-ended manner. Furthermore, the offenders’ reports support the prominent assumption that suspects’ perceptions of the evidence influence their decisions to confess or deny. Finally, in this study, many suspects reported that they had remained silent in both guilty and innocent interview situations. Reported motives were, for example, an attorney’s advice, protecting themselves against a misuse of their statements, or not talking to the police in general. We firmly believe that suspects should not be motivated to make statements against their will, and also see no need for further research here. However, these results also hint that there is room for improvement in terms of the perceived fairness of police interviews. To date, much research has focused on actionable outcomes of the interviews (e.g., amount of information, confessions). Future research can help to improve the quality of suspects’ interviews by also examining subjective measures such as perceived fairness.

Notes

Two participants did not provide information on their sex. In general, single missing values did not lead to exclusion of a participant’s complete data, and these were included in further statistical analyses.

The current study was part of a broader collection of data on suspect interviewing in Germany with distinctive research questions. In one study, May et al. (2021) examined suspects’ perceptions about their most recent suspect interview in which they had confessed to or denied a crime they reported having committed or not committed. Further topics of the questionnaire addressed (a) suspects’ planning of the interview and (b) their understanding of their rights during the interview. These data will be analyzed in different studies.

References

Appleby SC, Hasel LE, Kassin SM (2013) Police-induced confessions: an empirical analysis of their content and impact. Psychology, Crime & Law 19(2):111–128. https://doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2011.613389

Arndorfer A, Malloy LC, Cauffman E (2015) Interrogations, confessions, and adolescent offenders’ perceptions of the legal system. Law Hum Behav 39(5):503–513. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000138

Bond CF, DePaulo BM (2006) Accuracy of deception judgments. Pers Soc Psychol Rev 10:214–234. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr1003_2

Bürkner PC (2017) Brms: an R package for Bayesian multilevel models using Stan. J Stat Softw 80(1):1–28. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v080.i01

Bull R (2019) Roar or ‘PEACE’: Is it a “tall story?” In R. Bull & I. Blandon-Gitlin (Eds.), International handbook of legal and investigative psychology (pp. 19–36). Routledge/Taylor and Francis. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429326530

Cassell PG, Hayman BS (1996) Police interrogation in the 1990s: an empirical study of the effects of Miranda. UCLA Law Rev 43:839–931

Deslauriers-Varin N, Lussier P, St-Yves M (2011a) Confessing their crime: factors influencing the offender’s decision to confess to the police. Justice Q 28(1):113–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/07418820903218966

Deslauriers-Varin N, Beauregard E, Wong J (2011b) Changing their mind about confessing to police: the role of contextual factors in crime confession. Police Q 14(1):5–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098611110392721

European Committee for the Prevention of Torture and Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (2019) 28th general report of the CPT. Council of Europe. https://rm.coe.int/16809420e3

Gubi-Kelm S, Grolig T, Strobel B, Ohlig S, Schmidt AF (2020) When do false accusations lead to false confessions? Preliminary evidence for a potentially overlooked alternative explanation. Journal of Forensic Psychology Research and Practice. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/24732850.2020.1714388

Gudjonsson GH (2003) The psychology of interrogations and confessions. Wiley

Gudjonsson GH (2018) The psychology of false confessions: forty years of science and practice. Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119315636

Gudjonsson GH, Sigurdsson JF (1994) How frequently do false confessions occur? An empirical study among prison inmates. Psychology, Crime & Law 1(1):21–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683169408411933

Gudjonsson GH, Gonzalez RA, Young S (2021) The risk of making false confessions: the role of developmental disorders, conduct disorder, psychiatric symptoms, and compliance. J Atten Disord 25(5):715–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054719833169

Gudjonsson GH, Sigurdsson JF, Einarsson E (2004a) The role of personality in relation to confessions and denials. Psychology, Crime & Law 10(2):125–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160310001634296

Gudjonsson GH, Sigurdsson JF, Bragason OO, Einarsson E, Valdimarsdottir EB (2004b) Confessions and denials and the relationship with personality. Legal and Criminal Psychology 9:121–133. https://doi.org/10.1348/135532504322776898

Gudjonsson GH, Sigurdsson JF, Bragason OO, Newton AK, Einarsson E (2008) Interrogative suggestibility, compliance and false confessions among prisoners and their relationship with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) symptoms. Psychol Med 38(7):1037–1044. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291708002882

Gudjonsson GH, Sigurdsson JF, Einarsson E, Bragason OO, Newton AK (2010) Inattention, hyperactivity/impulsivity and antisocial personality disorder. Which is the best predictor of false confessions? Personality and Individual Differences 48(6) 720–724. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.01.012

Holmberg U, Christianson S-A (2002) Murderers’ and sexual offenders’ experiences of police interviews and their inclination to admit or deny crimes. Behavioural Science and the Law 20:31–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.470

Houston KA, Meissner CA, Evans JR (2014) Psychological processes underlying true and false confessions. In R. Bull (Ed.) Investigative interviewing (pp. 19–34). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-9642-7_2

Innocence Project (2021) DNA exonerations in the United States. Retrieved from https://www.innocenceproject.org/dna-exonerations-in-the-united-states/

Kassin SM (2005) On the psychology of confessions: does innocence put innocents at risk? Am Psychol 60:215–228. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.60.3.215

Kassin SM, Drizin SA, Grisso T, Gudjonsson GH, Leo RA, Redlich AD (2010) Police-induced confessions: risk factors and recommendations. Law and Human Behaviour 34:3–38. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-009-9188-6

Kassin SM, Goldstein CC, Savitsky K (2003) Behavioural confirmation in the interrogation room: on the dangers of presuming guilt. Law and Human Behaviour 27(2):187–203. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022599230598

Kassin SM, Leo RA, Meissner CA, Richman KD, Colwell LH, Leach A-M, La Fon D (2007) Police interviewing and interrogation: a self-report survey of police practices and belief. Law and Human Behaviour 31:381–400. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-006-9073-5

Kassin SM, Norwick RJ (2004) Why people waive their Miranda rights: the power of innocence. Law and Human Behaviour 28(2):211–221. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:LAHU.0000022323.74584.f5

Kassin SM, Wrightsman LS (1985) The psychology of evidence and trial procedure. Sage

Lenth RV (2021) Emmeans: estimated marginal means, aka least-squares means (R package version 1.6.3) [Computer software]. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=emmeans

Leuschner F, Rettenberger M, Dessecker A (2019) Imprisoned but innocent: wrongful convictions and imprisonments in Germany, 1990–2016. Crime Delinq 66(5):687–711. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128719833355

Leo RA (1996) Inside the interrogation room. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 86(2):266–303

Lord A, Willmot P (2004) The process of overcoming denial in sexual offenders. J Sex Aggress 10(1):51–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600410001670937

Madon S, Guyll M, Scherr KC, Greathouse S, Wells G (2012) The differential effect of proximal and distal consequences on confession decisions. Law Hum Behav 36:13–20. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0093962

Malloy LC, Shulman EP, Cauffman E (2014) Interrogations, confessions, and guilty pleas among serious adolescent offenders. Law Hum Behav 38(2):181–193. https://doi.org/10.1037/lhb0000065

May L, Gewehr E, Zimmermann J, Raible Y, Volbert R (2021) How guilty and innocent suspects perceive the police and themselves: suspect interviews in Germany. Leg Crim Psychol 26:42–61. https://doi.org/10.1111/lcrp.12184

Meissner CA (2021) What works? Applied Cognitive Psychology. Online publication, Systematic reviews and meta-analyses of the investigative interviewing research literature. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3808

Meissner CA, Redlich AD, Michael SW, Evans JR, Camilletti CR, Bhatt S, Brandon S (2014) Accusatorial and information-gathering interrogation methods and their effects on true and false confessions: a meta-analytic review. J Exp Criminol 10(4):459–486. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11292-014-9207-6

Moston S, Engelberg T (2011) The effects of evidence on the outcome of interviews with criminal suspects. Police Pract Res Int J 12(6):518–526. https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2011.563963

Moston S, Stephenson G (2009) A typology of denial strategies by suspects in criminal investigations. In R. Bull, Valentine T, Williamson T (Eds.), Handbook of psychology of investigative interviewing: current developments and future directions (pp. 17–34). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470747599.ch2

The National Registry of Exonerations (2021). False confessions. https://www.law.umich.edu/special/exoneration/Pages/False-Confessions.aspx

Principles on Effective Interviewing for Investigations and Information Gathering, May 2021, Retrieved from: www.interviewingprinciples.com

Redlich AD, Summers A, Hoover S (2010) Self-reported false confessions and false guilty pleas among offenders with mental illness. Law and Human Behaviour 34(1):79–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-009-9194-8

R Core Team (2020) R: a language and environment for statistical computing [Computer software]. https://www.R-project.org/

Scherr KC, Albers KM, Franks AS, Hawkins A (2016) Overcoming innocents’ naiveté: pre-interrogation decision-making among innocent suspects. Behav Sci Law 34:564–579. https://doi.org/10.1002/bsl.2247

Sigurdsson JF, Gudjonsson GH (1994) Alcohol and drug intoxication during police interrogation and the reasons why suspects confess to the police. Addiction 89:985–997. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-0443.1994.tb03358.x

Sigurdsson JF, Gudjonsson GH (1996a) The relationship between types of claimed false confession made and the reasons why suspects confess to the police according to the Gudjonsson Confession Questionnaire (GCQ). Leg Criminol Psychol 1(Part 2):259–269

Sigurdsson JF, Gudjonsson GH (1996b) The psychological characteristics of “false confessors.” A study among Icelandic prison inmates and juvenile offenders. Pers Individ Differ 20(3):321–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(95)00184-0

Sigurdsson JF, Gudjonsson GH (2001) False confessions: the relative importance of psychological, criminological and substance abuse variables. Psychology, Crime & Law 7(3):275–289. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160108401798

Sigurdsson JF, Gudjonsson GH, Emil Einarsson E, Gudjonsson G (2006) Differences in personality and mental state between suspects and witnesses immediately after being interviewed by the police. Psychol Crime Law 12(6):619–628. https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160500337808

Viljoen JL, Klaver J, Roesch R (2005) Legal decisions of preadolescent and adolescent defendants: predictors of confessions, pleas, communication with attorneys, and appeals. Law Hum Behav 29(3):253–277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10979-005-3613-2

Volbert R, May L, Hausam J, Lau S (2019) Confessions and denials when guilty and innocent: forensic patients’ self-reported behavior during police interviews. Front Psych 10:168. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00168

Vredeveldt A, van Koppen PJ, Granhag PA (2014) The inconsistent suspect: a systematic review of different types of consistency in truth tellers and liars. In R. Bull (Ed.), Investigative interviewing (pp. 183–207). Springer Science + Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-9642-7_10

Acknowledgements

We thank Miriam Bach, Jasmin Ghalib, Clara Goers, Caroline Huss, Pauline Lauda, Claudia Zimmermann, and Pierre Pantazidis for their help with data collection.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

May, L., Raible, Y., Gewehr, E. et al. How Often and Why Do Guilty and Innocent Suspects Confess, Deny, or Remain Silent in Police Interviews?. J Police Crim Psych 38, 153–164 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-022-09522-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11896-022-09522-w