Abstract

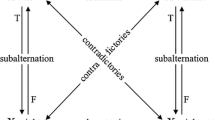

In the recent debate on future contingents and the nature of the future, authors such as G. A. Boyd, W. L. Craig, and E. Hess have made use of various logical notions, such as (the difference between) the Aristotelian relations of contradiction and contrariety, and the ‘open future square of opposition.’ My aim in this paper is not to enter into this philosophical debate itself, but rather to highlight, at a more abstract methodological level, the important role that Aristotelian diagrams (such as the open future square of opposition, but also others) can play in organizing and clarifying the debate. After providing a brief survey of the specific ways in which Boyd and Hess make use of Aristotelian relations and diagrams in the debate on the nature of the future, I argue that the position of open theism is best represented by means of a hexagon of opposition (rather than a square of opposition). Next, I show that on the classical theist account, this hexagon of opposition ‘collapses’ into a single pair of contradictory statements. This collapse from a hexagon into a pair has several aspects, which can all be seen as different manifestations of a single underlying change (viz., the move from a tripartition to a bipartition of logical space).

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

In Demey (2017) it is argued that Aristotelian diagrams can play a similar heuristic role in pedagogical contexts.

By itself, the thesis of the alethic openness of the future is neutral with respect to the question whether the principle of bivalence applies to future contingents. Open theists such as Boyd, Rhoda and Hess retain bivalence; they hold that neither ‘x will obtain at t’ nor ‘x will not obtain at t’ is true, because both these statements are false. By contrast, open theists such as Tuggy (2007) reject bivalence for future contingents; they hold that neither ‘x will obtain at t’ nor ‘x will not obtain at t’ is true, because both these statements lack a truth value altogether (they are neither true nor false). See Rhoda (2008, p. 229; 2011, p. 75) for more discussion.

Even when Hess (2017, p. 5) talks about the disjunction of these statements (‘might or might not’), he emphasizes that this disjunction is inclusive in nature, and focuses on the case where it is true because both individual statements are true, thereby implicitly still getting at the conjunction after all (cf. ‘the conjoint truth of “might” and “might not”’, 2017, p. 6, my emphasis). Furthermore, elsewhere in the paper (e.g. on p. 6) Hess explicitly talks about the conjunction (‘might and might not’).

As will be argued in the next section, the classical theist takes this disjunction (‘will or will not’) not only to be true, but even to be tautological in nature.

Hess briefly hints at these two additional contrarieties, when noting that the ‘[con]junction […] actually negates both “will” and “will not” propositions’ (2017, p. 6); also see Footnote 4.

Also see Boyd (2010, p. 53) and Hess (2017, p. 2, Footnote 2). Note that equivalences (3) and (6) are trivial, because they merely involve the reformulation of the logical operations of ∧ and ∨ into their natural language counterparts ‘and’ and ‘or’. Nevertheless, I have explicitly included equivalences (3) and (6) here, in order to emphasize their structural similarity to equivalences (1–2) and (4–5), respectively.

It is interesting to note that the three discoverers of the JSB hexagon all worked in a distinctly religious (viz., Catholic) intellectual context. See Jaspers and Seuren (2016) for a detailed historical analysis of the broader cultural background to this observation.

Also recall the quotation given in the final paragraph of the previous section.

In particular, Hess distinguishes between two different readings of the word ‘will’ in the phrase ‘it will be the case that,’ viz., the posterior present reading and the simple future tense reading (the exact details of these two readings need not concern us here). He then goes on to argue, first, that ‘will’ and ‘will not’ under ‘the posterior present reading […] can be seen to have different truth conditions, which means that they are not, strictly speaking, logically equivalent propositions’ (2017, p. 8), and secondly, that they ‘—even on a simple future tense reading—still are not logically equivalent statements’ (2017, p. 10).

In an unpublished manuscript entitled ‘The Hexagon of Opposition: Thinking Outside the Aristotelian Box’, Boyd, Belt and Rhoda anticipate several of the arguments presented in the current paper. In particular, they also develop a hexagon of opposition for representing the position of open theism, although they proceed in a different way than I do here. Furthermore, that paper does not provide a bitstring analysis of the hexagon, and does not discuss the ‘collapse’ from a JSB hexagon (for open theism) into a single pair of contradictory statements (for classical theism). Boyd, Belt and Rhoda’s paper can be found online at http://reknew.org/2008/01/the-hexagon-essay/ (accessed on 28 August 2017); I would like to thank an anonymous reviewer of this journal for bringing it to my attention.

References

Blanché, R. (1953). Sur l’opposition des concepts. Theoria, 19, 89–130.

Blanché, R. (1966). Structures intellectuelles. Essai sur l’organisation systématique des concepts. Paris: Vrin.

Boyd, G. A. (2010). Two ancient (and modern) motivations for ascribing exhaustively definite foreknowledge to God: a historic overview and critical assessment. Religious Studies, 46, 41–59.

Boyd, G. A. (2011). God limits his control. In D. W. Jowers (Ed.), Four views on divine providence (pp. 183–208). Grand Rapids: Zondervan.

Craig, W. L. (1999). The only wise God: the compatibility of divine foreknowledge and human freedom. Eugene, OR: Wipf & Stock Publishers.

Craig, W. L. (2011). Response to Gregory A. Boyd. In D. W. Jowers (Ed.), Four views on divine providence (pp. 224–230). Grand Rapids: Zondervan.

Demey, L. (2015). Interactively illustrating the context-sensitivity of Aristotelian diagrams. In H. Christiansen, I. Stojanovic, & G. Papadopoulos (Eds.), Modeling and using context (pp. 331–345). Berlin: Springer.

Demey, L. (2017). Using syllogistics to teach metalogic. Metaphilosophy, 2017, 575–590.

Demey, L., & Smessaert, H. (2016). Metalogical decorations of logical diagrams. Logica Universalis, 10, 233–292.

Demey, L., & Smessaert, H. (2017). Combinatorial bitstring semantics for arbitrary logical fragments. Journal of Philosophical Logic forthcoming.

Hartshorne, C. (1965). The meaning of ‘is going to be’. Mind, 74, 46–58.

Hess, E. (2017). The open future square of opposition: a defense. Sophia forthcoming.

Jacoby, P. (1950). A triangle of opposites for types of propositions in Aristotelian logic. New Scholasticism, 24, 32–56.

Jaspers, D., & Seuren, P. A. M. (2016). The square of opposition in Catholic hands: a chapter in the history of 20th-century logic. Logique et Analyse, 59(233), 1–35.

Pizzi, C. (2016). Generalization and composition of modal squares of oppositions. Logica Universalis, 10, 313–325.

Rhoda, A. R. (2008). Generic open theism and some varieties thereof. Religious Studies, 44, 225–234.

Rhoda, A. R. (2011). The fivefold openness of the future. In W. Hasker, T. J. Oord, & D. Zimmerman (Eds.), God in an open universe: science, metaphysics, and open theism (pp. 69–93). Eugene: Pickwick.

Rhoda, A. R., Boyd, G. A., & Belt, T. G. (2006). Open theism, omniscience, and the nature of the future. Faith and Philosophy, 23, 432–459.

Sesmat, A. (1951). Logique II. Les raisonnements. La syllogistique. Paris: Hermann.

Smessaert, H. (2009). On the 3D visualisation of logical relations. Logica Universalis, 3, 303–332.

Smessaert, H., & Demey, L. (2014). Logical geometries and information in the square of oppositions. Journal of Logic, Language and Information, 23, 527–565.

Smessaert, H., & Demey, L. (2017). The unreasonable effectiveness of bitstrings in logical geometry. In J.-Y. Béziau & G. Basti (Eds.), The square of opposition: a cornerstone of thought (pp. 197–214). Basel: Springer.

Tuggy, D. (2007). Three roads to open theism. Faith and Philosophy, 24, 28–51.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Hans Smessaert, Margaux Smets, and three anonymous reviewers for their valuable feedback on an earlier version of this paper. The research reported in this paper is financially supported through a Postdoctoral Fellowship of the Research Foundation–Flanders (FWO), and was partially carried out during research stays at the Faculty of Philosophy of the University of Oxford (Spring 2017) and at the Institut für Philosophie II of the Ruhr-Universität Bochum (Summer 2017).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Demey, L. Aristotelian Diagrams in the Debate on Future Contingents. SOPHIA 58, 321–329 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11841-017-0632-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11841-017-0632-7