Abstract

This work investigated the influence of two types of mooring systems on the hydrodynamic performance of a two-body floating wave energy converter (WEC). It also investigated the effects of the physical parameters of the mooring system on the amount of extractable power from incident waves in the frequency domain. The modeled converter comprised a floating body (a buoy), a submerged body with two mooring systems, and a coupling system for two bodies. The coupling system was a simplified power take-off system that was modeled by a linear spring-damper model. The tension leg mooring system could drastically affect the heave motion of the submerged body of the model and increase relative displacement between the two bodies. The effects of the stiffness parameter of the mooring system on power absorption exceeded those of the pretension tendon force.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Various devices have been designed, tested, and optimized for the extraction of ocean wave energy. Some relevant successes have been achieved in recent years. For example, two-body point absorber wave energy converters (WECs) have been developed as promising systems for energy generation from ocean waves, and their hydrodynamic analysis has become an important research topic (Amiri et al. 2016). Various WECs are under development and testing at Ocean Power Technologies (OPT), the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, USA, and the University of Victoria, Canada. A new utility scale of the two-body point absorber WEC was recently tested by OPT at Invergordon, Scotland. In a two-body point absorber WEC, energy is extracted from waves through the relative displacement between the buoy and submerged body in heave motion (Beatty et al. 2015; Liang and Zuo 2017; Sinha et al. 2016; Guedes Soares et al. 2014).

Falnes and Perlin (2003) investigated the feasibility of applying the relative motion between two bodies to capture wave energy. They found that in regular waves, the optimum power for an oscillating two-body converter can be achieved during heaving. Then, Korde (2003) explored the concept of the heave relative motion of WECs. He compared the performance of two-body WECs with reaction bodies in two modes (fully immersed and out of water). He found that the fully submerged body performed better than the out-of-water body in a two-body WEC.

The conversion efficiency and response of a two-body WEC in regular waves were studied by Wu et al. (2014). They found that the performance of a two-body WEC was highly dependent on system parameters, such as buoy physical properties and incident wave frequency. Muliawan et al. (2013) studied the effect of the power take-off (PTO) properties and several configurations of a taut mooring system on power extraction by a two-body wavebob-type WEC used to capture wave power at the Yen site in France. They found that mooring exerted a considerable effect on energy production. This effect was dependent on mooring configuration, properties, and sea-state condition.

Yu et al. (2013) conducted a numerical study by using WAMIT and performed some experiments on a two-body floating-point absorber WEC at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory. In their research, the two-body WEC comprised two parts that were connected through a linear mass-spring-damper system to represent the PTO mechanism. The system was predominantly operated in heave motion and was limited to single-degree-of-freedom motion (in heave). Moreover, the effect of the mooring system was ignored.

Beatty et al. (2015) compared the hydrodynamic performances of two types of submerged bodies similar to those in Wavebob and Powerbuoy WEC. They studied and compared the heave motion and hydrodynamics of two 1:25 scale physical models of the two WEC devices with a horizontal three-point taut mooring system. They focused on the geometric form and heave oscillation of the submerged body under regular wave excitations but ignored the influence of the mooring system.

The present study investigated the hydrodynamic performance of a two-body WEC heaving in regular waves. This work aimed to study the effects of the mooring system and its physical parameters on the heave motion of the two bodies of the converter and on the power extracted from incident waves by a coupled linear spring-damping system. The effects of the tendon stiffness of the mooring system and their pretension variation on the heave motion of the model were investigated through frequency-domain analysis.

2 The two-body WEC model

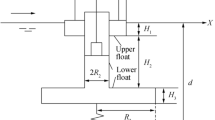

Figure 1 shows the schematic of the two-body wave energy converter considered in this paper, which consisted of a floating body (an absorber buoy), a submerged body with a reaction plate, and a mass-spring-damper system. The buoy is located on the water surface and is connected to the submerged floating body through a PTO system. The PTO system is modeled by a linear spring-damping system that is referred to as the coupling system. The geometry and dimensions of the model are the same as those of the experimental model investigated by Yu et al. (2013).

Two bodies of the model (the buoy and submerged body) are axisymmetric, and incident waves are assumed to be unidirectional. This assumption restricted the analysis to the translational motion of model. The effects of very slow variations in water surface, such as tidal oscillations, sea currents, coupling weight, mooring system weight, and other environmental conditions on the model are neglected, and the friction inside the PTO system is not modeled. The seabed is assumed to be smooth and without slope. The effects of the nonlinear interaction between waves and the model, viscous damping, and wave overtopping are not investigated in this study.

The translational motions of surge and sway would be acceptably restrained for the two bodies by adopting very long elastic cables along the x- and y-directions between the far universal fixed joints and the buoy and submerged body in the modeling of ANSYS Aqwa. Thus, similar to the model used by Yu et al. (2013), the model in the present study oscillated only along the z-direction. The model mainly operates in heave motion. Here, the incident wave is assumed to be a unidirectional regular wave with a height of 2.5 m and a period of 10 s. The linear spring stiffness and damping coefficient of the coupling system are 20 kN/m and 1200 kN s/m, respectively, and are similar to those of the coupling system used in the numerical study by Yu et al. (2013).

Figures 2 and 3 present the comparative hydrodynamic analyses of the model under identical conditions for the heave oscillation of the two bodies of the model. Figure 2 shows the heave oscillation amplitude that was rendered nondimensional with the initial thickness of the buoy (e = 2 m). Figure 3 shows the response amplitude operator (RAO) of the two bodies of the model for the heave motion results from the frequency-domain hydrodynamic analysis versus the dimensionless parameter of incident wave frequency ω∗, that is, \( {\upomega}^{\ast }=\upomega \sqrt{D_{\mathrm{R}}/g} \). The parameters ω, DR, and g represent wave frequency, reaction plate diameter, and gravitational acceleration, respectively.

Heave motion of the buoy and submerged body in this study and in the study by Yu et al. (2013)

Results from frequency-domain analysis in this study and in the research by Yu et al. (2013): the RAO of two bodies in heave versus wave frequency

Comparing the results of the present research with those of the work by Yu et al. (2013) revealed that the computational and modeling errors for the buoy and submerged body were 6.8% and 7.1%, respectively, and were acceptable in a time series.

3 Comparison of the two types of mooring systems

Given its low cost and proper performance, the three-point taut mooring (TPM) system has been widely used to maintain the position and stability of point absorber WECs within the marine environment. Beatty et al. (2015) used this mooring system in experiments. He modeled and tested a model scale of the two-body PowerBuoy WEC. The TPM system used in the PowerBuoy WEC and fabricated by the OPT is illustrated in Fig. 4 (Beatty et al. 2015).

First, two types of mooring systems were considered to investigate the effect of the mooring system on the hydrodynamic performance of a heaving two-body WEC model: the TPM system and tension-leg mooring (TLM) system. A schematic of the two mooring systems is shown in Figs. 5 and 6. The TLM system is not a new system in the maritime industry but is rarely used in WEC devices. Multiple tension legs are typically utilized in oil platforms and wind turbines (Zhao et al. 2012). The TLM system, which comprises a set of parallel lines, connects the submerged body to a structure fixed to the sea bottom or to an equivalent support (Fig. 6).

The submerged body’s buoyancy force, which acts as a tension force in the mooring lines of the TLM system, is larger than its weight. By contrast, in the TPM system, the buoyancy force of the three fully immersed spherical buoys of the system (as seen in Fig. 4) acts as the tension force in mooring lines.

The pretension force of tendons, the physical properties of mooring systems, and environmental conditions were considered to be the same for the two scenarios (Figs. 5 and 6). Frequency-domain analysis was performed with ANSYS Aqwa to analyze the model in two different mooring system scenarios. ANSYS Aqwa is a multibody hydrodynamic program that is based on three-dimensional radiation and diffraction theory and is used to analyze the mooring system and hydrodynamics of bodies in the marine environment.

The region of validity of diffraction theory is determined using two criteria: the diffraction parameter D/λ and viscous H/D. The ratio of the buoy diameter to the incident wavelength (DB/λ) is approximately between 0.03 and 0.57, and the wave height-to-buoy diameter ratio is 0.113 (H/DB ≅ 0.11). Therefore, the diffraction theory will be valid on the basis of the graphs of the region of validity of potential flow theory (Kvittem et al. 2012).

Subsequently, the effects of the two mooring systems on the heave oscillation of the two bodies and the efficiency of the model were compared.

In the two scenarios of the mooring system, the maximum heave displacement of the buoy was obtained during the excitation of waves with different frequencies and heights of 1.25 m. In addition, the heave oscillation amplitude of the submerged body was obtained in the time interval when the oscillation amplitude of the buoy is at the maximum value. Figures 7 and 8 show the ratio of the results to the initial thickness of the buoy (e = 2 m). This ratio is denoted as H∗.

The small difference between the heave motions of the buoy in the two different mooring system scenarios (as seen in Fig. 7) is attributed to the low spring stiffness of the coupling system and the large diameter of the buoy. Varying the drift of the buoy changes the buoyancy force because of the large buoy diameter. The created force in the spring attributed to the heave displacement of the submerged body fails to drastically change the drift of the buoy.

The effects of the TPM and TLM systems on the heave motion of the submerged body are illustrated in Fig. 8. The largest difference in the heave oscillation of the submerged body between the two mooring scenarios was observed under the incident frequency wave of approximately 0.9 rad/s (ω∗ ≅ 1.08). The maximum difference was approximately 22 cm.

The heave oscillation amplitude of the buoy when the TPM system was used in the model was slightly larger than that when the TLM system was applied because of the increased displacement of the submerged body in the first mooring system scenario.

The heave oscillation of the submerged body drastically decreased when the TLM system was applied relative to that when the TPM system was employed (Fig. 8).

These results indicate that the relative heave displacement between the two bodies considerably increased when the TLM system was applied relative to that when the TPM system was used.

As previously stated, the efficiency of a two-body WEC is ascribed to the relative displacement between its two bodies along heave motion. The efficiency of the model increased when the oscillation of the buoy increased and the swing of the submerged body decreased during heaving.

In regular waves, the time-averaged power absorbed by the wave energy absorber buoy Pabs can be obtained as

where \( {Z}_{\mathrm{B}}^{\mathrm{i}} \) and \( {Z}_{\mathrm{R}}^{\mathrm{i}} \) denote the heave oscillation amplitude of the buoy and submerged body in the wave at ith frequency (ωi), respectively. The parameter bext is the linear external damping coefficient that originates from the simplified PTO system (the coupling system) to enable power absorption. Maximum power absorption occurs when relative displacement between the two bodies \( \mid {Z}_{\mathrm{B}}^i-{Z}_{\mathrm{R}}^i\mid \) is maximized.

The power extracted, when each of the mooring systems was applied in the model, is shown in Fig. 9. The effect of the TLM system on the absorbed power was more remarkable than that of the TPM system. This effect was particularly pronounced for incident waves with frequencies of 0.7 to 1.25 rad/s. Therefore, the TLM system was selected for the model, and the effect of the physical parameters of the TLM on the improvement of the heave motion of the model was investigated.

For the evaluation of the pitch motion of the two bodies on the efficiency of the WEC model, frequency-domain analysis was performed to estimate the RAO of each body for pitch motion under TPM and TLM conditions. Figures 10 and 11 show the RAOs of the two bodies for the pitch motion results of the hydrodynamic analysis when each of the mooring systems was applied to the model.

The RAO of the submerged body for the pitch motion was close to zero because of the large diameter of the heave plate (14 m). In addition, the center of the gravity of the submerged body was located 22.4 m below the mean free surface. The approximately identical pitch motions of the buoy in two different modes of mooring system resulted from the low stiffness of the coupling spring.

The maximum pitch angle of the buoy was approximately 5° (\( {\upbeta}_{\max_{\mathrm{B}}}={5.15}^{\circ } \)). The distance between the global axis system and the center of the gravity of the buoy and the submerged body were 1.5 and 37.3 m, respectively. Therefore, the maximum displacement of the buoy along the z-direction will be approximately 0.00606 m because of the change in pitch angle. Figures 12 and 13 show the vertical maximum displacement of the buoy and submerged body that results from the change in the pitch angle in each incident wave versus the dimensionless parameters H∗P and ω∗. The parameter H∗P is the ratio of the heave displacement of each body to the thickness of the buoy (e) at this stage.

The order of the parameter H∗P resulting from pitch motion is approximately O(10−4–10−3) for the buoy and is approximately O(10−5) for the submerged body. By contrast, the order was O(10−1) for heave motion. Therefore, the heave motion of the two bodies will predominate in this case study, and the effect of heave motion on the power absorption performance of the model will be insignificant against that of pitch motion.

4 Model with the TLM system

The TLM system was applied to study the effect of tendon parameters on the heave motion of the two bodies. The TLM system had three pretension tendons. The angle between tendons was 120° (Fig. 5).

The tensile mooring system design is sensitive to environmental conditions, particularly noncollinear environmental factors, weak currents, and large waves. Environmental conditions affect the design and analysis of tension-leg structures (Chen and Zhang 2017). Some assumptions were considered as described in “Section 2.” In addition, environmental effects were ignored.

The pretension force in the mooring tendons is generated by the buoyancy force applied to the submerged body when the buoyancy of the submerged body exceeds its weight. Therefore, to induce tendon pretension, the mass of the submerged body (mR) was assumed to be as follows:

where ∀R represents the submergence volume of the submerged body. Parameters ρ and gdenote water density and gravitational acceleration, respectively and are assumed to be 1025 kg/m3 and 9.806 m/s2, respectively. Parameter FM is the pretension in each tendon and is assumed to be 200 kN under calm sea conditions.

The governing linear equations of motion for the heaving buoy and submerged body will be obtained through the usual linear decomposition of the hydrodynamic forces (Faiz and Ebrahimi-Salari 2011; Liang and Zuo 2017) and are

where Z is the complex amplitude of the bodies’ position along heave motion, and m is the mass of the buoy and submerged body with a reaction plate. Subscripts B and R represent the buoy and submerged body, respectively. Parameter KM is the tendon heave stiffness. Ks is the hydrostatic restoring coefficient. It is dependent on the water plane area and is Ks = ρgπDB2/4. The parameters Az and Cz are the hydrodynamic coefficients of added mass and damping for heave motion (with subscript z), respectively. The hydrodynamic force Fz is the vertical component of the wave-induced excitation force on the buoy and submerged body. The parameter FPTO is the PTO force and is represented by a spring-damping force, as follows:

Here, \( \dot{Z} \) and Z are the heave velocity and displacement of the buoy and submerged body with subscripts B and R, respectively. Parameters Ksp and bext are the linear spring stiffness coefficient and the linear damping coefficient in the coupling system, respectively.

The hydrodynamic parameters are dependent on body shape and wave frequency. The numerical values for the hydrodynamic parameters were obtained with the aid of the boundary element code AQWA. Figures 14 and 15 show the added mass and damping dimensionless coefficients of the two bodies in the heave motion. Analogously to Lopez-Pavon and Souto-Iglesias (2015), the coefficients are rendered nondimensional with the theoretical added mass of a disk oscillating in heave similar to the reaction plate, \( {A}_{{\mathrm{z}}_{\mathrm{th}}} \). The dimensionless coefficients Az∗ and Cz∗ are defined as

4.1 Parameters of the TLM system

In the two-body WEC, the mooring system directly affects the dynamics of the submerged body, and the dynamics of the submerged body affects the amount of relative displacement between the floating and submerged bodies of the converter. As a result, the physical parameters and configuration type of the mooring system and the pretension force of the tendons affect the dynamics of the two bodies and the power output of the two-body WEC.

We defined dimensionless values to simplify the investigation of the effect of the physical parameters of the TLM system on model dynamics. These parameters included the stiffness and pretension parameter of the mooring lines (tendons). The dimensionless values are denoted by an asterisk, for example, FM∗ = FM/(πr2eρg), KM∗ = KM/Ksp, and Z∗ = ∣ Zmax ∣ /Aw.

The minimal values for the parameters of the coupling system recommended by Yu et al. (2013) were used to maintain the connection between the two bodies in regular waves. Thus, the minimum values for the linear spring coefficient and damping coefficient of the coupling system were selected as 20 kN/m and 80 kN/(m/s), respectively. Then, the dynamics of the two bodies in the unidirectional regular waves of various angular frequency ω and height 1.25 m and three different values for the dimensionless parameter of tendons stiffness KM∗ were investigated. The curves in Fig. 16 show the ratio of the heave oscillation amplitude of the buoy to the incident wave amplitude for KM∗ = 5, 10, 20. This ratio was designated as Z∗.

The ratio of the heave oscillation amplitude of the submerged body to the incident wave amplitude in the time interval when the oscillation amplitude of the buoy was maximized was designated as Zt. Figure 17 shows the value of Zt in the time interval when the oscillation amplitude of the buoy was maximized. As shown in Figs. 16 and 17, the tendon stiffness parameter remarkably affected the heave motion of the submerged body but negligibly affected the oscillation of the buoy.

By increasing the values of the parameter KM∗, the oscillation amplitude of the submerged body in heave drastically decreased, whereas that of the buoy negligibly decreased (Figs. 16 and 17). As a result, the relative displacement between the two bodies of the model increased. Given that the absorbed power was associated with relative displacement, the power output also increased.

The power (in kW) absorbed by the model for each incident wave at this stage was calculated by using Eq. (1) and the values of Z∗ and Zt. The results are shown in Fig. 18. The curves show the effect of increasing KM∗ by 100% on the absorbed power. The parameter \( {\overline{P}}_{\mathrm{abs}} \) was defined to simplify the comparison of the results for the three modes of KM∗. This parameter was obtained by averaging the absorbed power over the range of all incident waves. The results described in Table 1 show that the maximum value of \( {\overline{P}}_{\mathrm{abs}} \) was obtained whenKM∗ = 20.

The theoretical maximum limit of the time-averaged power that an axisymmetric heaving wave energy converter can absorb from regular waves with frequency ω and amplitude Aw is Pmax, which corresponds to capture width λ/2π where λ is wavelength (Vicente et al. 2013). A dimensionless power absorption coefficient P∗, which is the absorption efficiency of the model, was defined as follows:

The curves of the dimensionless coefficient of the absorbed power (P∗) show the superiority of the system under the condition of KM∗ = 20 in power absorption from incident waves (Fig. 19). Three parameters are defined in Table 1 to simplify the comparison of the results for this stage. These parameters include \( {\overline{P}}_{\mathrm{abs}} \), \( {\overline{P}}^{\ast } \), and the incremental percentage of the parameter \( {\overline{P}}_{\mathrm{abs}} \). The parameter \( {\overline{P}}_{\mathrm{abs}} \) is the average absorbed power in the range of the waves. The parameter \( {\overline{P}}^{\ast } \) is the average efficiency of the model for each value of KM∗ over the range of incident waves. The difference between \( {\overline{P}}_{\mathrm{abs}} \) attributed to the 100% variation in parameter KM∗ was denoted as an incremental percentage of \( {\overline{P}}_{\mathrm{abs}} \). The increment in the percentage of absorbed average power with the change in mooring properties can thus be explained.

The results provided in Table 1 show that increasing tendon stiffness will always increase the absorbed power. Thus, by increasing the coefficient KM∗ from 5 to 10 and then to 20, the absorbed power increased by approximately 7% to 10.7%. The variation in tendon stiffness increased \( {\overline{P}}_{\mathrm{abs}} \) by 10.7% from 16 to 20 kW.

The model was analyzed by using three different values of FM∗ to study the effect of the tendon pretension parameter. Similar to tendon stiffness, the pretension force of the tendons had a negligible effect on the heave oscillation of the buoy under incident wave excitation but had a drastic effect on the heave motion of the submerged body. Increasing FM∗ increased the extracted power. Nevertheless, the effect of FM∗ was weaker than that of KM∗.

Figures 20 and 21 show the dimensionless values of Z∗ and Zt for the buoy and submerged body versus incident wave frequency for different values of FM∗, respectively. The curves show the effect of increasing FM∗ by 100% on the heave motion of the two bodies of the model.

The power extracted from each incident wave and absorption efficiency is shown in Figs. 22 and 23, respectively. The curves presented in Fig. 22 show the influence of increasing tendon pretension by 100% on the absorbed power. The summary of the results for different modes of FM∗ is given in Table 2. The results show that increasing the parameter FM∗ by 100% increased \( {\overline{P}}_{\mathrm{abs}} \) from 0.12% to 0.46%.

Although changes in tendon pretension did not drastically affect parameters \( {\overline{P}}_{\mathrm{abs}} \) and P∗ for the range of all waves, this influence was evident in the range of wave frequencies 0.7 up to 1.1 rad/s. In this range, the parameter \( {\overline{P}}_{\mathrm{abs}} \) was superior in FM∗ = 0.114.

Comparing the results obtained by changing mooring stiffness and tendon pretension revealed that the effect of the mooring stiffness coefficient on the heave motion behavior of two bodies and absorbed power was more intense than that of the pretension parameter. In fact, under the above conditions, the absorbed power consistently increased when the mooring stiffness coefficient increased. However, the effect of the pretension parameter of mooring lines (FM∗) on the increase in the absorbed average power is negligible compared with that of the other coefficient.

5 Conclusions

This study aimed to compare the influence of two types of mooring systems on the heave motion of a two-body WEC. A two-body floating WEC comprising a buoy and a submerged body with two separate mooring systems was considered. A coupling system, which was a simplified linear model of the PTO system in the WEC and that consisted of a linear spring and a linear damper located between the two bodies, was employed.

The model is moored to the seabed by the tension-leg mooring (TLM) system or three-point taut mooring (TPM) system. The model with the TLM or TPM systems was analyzed and compared. The results indicated that the TLM system drastically improved the heave relative motion of two bodies and power absorption compared to the TPM system.

The TLM system showed outstanding performance in preventing the heave motion of the submerged body and increasing the relative heave displacement between the two bodies of the model. Therefore, the TLM system was considered as the mooring system in the investigation of the influence of physical parameters on the heave motion behavior of the model. Subsequently, to study the influence of the TLM parameters on the heave motion of two bodies, two parameters, including the stiffness and pretension force of the mooring tendons, were considered.

Mooring tendon stiffness more effectively improved the heave motion of the two bodies and absorbed power than the tendon pretension parameter. Increasing mooring stiffness by 100% increased the amount of absorbed power by 7% to 10%. By contrast, increasing the pretension parameter by 100% only increased the amount of absorbed power by 0.11% to 0.5%. Therefore, the power absorbed by the heaving two-body WEC increased as the stiffness of the mooring tendon stiffness increased.

References

Amiri A, Panahi R, Radfar S (2016) Parametric study of two-body floating-point wave absorber. J Mar Sci Appl 15(1):41–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11804-016-1342-1

Beatty SJ, Hall M, Buckham BJ, Wild P, Bocking B (2015) Experimental and numerical comparisons of self-reacting point absorber wave energy converters in regular waves. Ocean Eng 104:370–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2015.05.027

Chen Y, Zhang D (2017) Response-based analysis for tension leg platform. J Mar Sci Appl 16(1):87–92. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11804-017-1390-1

Faiz J, Ebrahimi-Salari M (2011) Comparison of the performance of two direct wave energy conversion systems: Archimedes wave swing and power buoy. J Mar Sci Appl 10(4):419–428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11804-011-1087-9

Falnes J, Perlin M (2003) Ocean waves and oscillating systems: linear interactions including wave-energy extraction. Appl Mech Rev 56:B3. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.1523355

Guedes Soares C, Bhattacharjee J, Karmakar D (2014) Overview and prospects for development of wave and offshore wind energy. Brodogradnja 65(2):87–109. https://hrcak.srce.hr/123506. Accessed 10 Dec 2018

Korde UA (2003) Systems of reactively loaded coupled oscillating bodies in wave energy conversion. Appl Ocean Res 25(2):79–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0141-1187(03)00044-0

Kvittem MI, Bachynski EE, Moan T (2012) Effects of hydrodynamic modelling in fully coupled simulations of a semi-submersible wind turbine. Energy Procedia 24:351–362. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.egypro.2012.06.118

Liang C, Zuo L (2017) On the dynamics and design of a two-body wave energy converter. Renew Energy 101:265–274. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2016.08.059

Lopez-Pavon C, Souto-Iglesias A (2015) Hydrodynamic coefficients and pressure loads on heave plates for semi-submersible floating offshore wind turbines: a comparative analysis using large scale models. Renew Energy 81:864–881. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2015.04.003

Muliawan MJ, Gao Z, Moan T, Babarit A (2013) Analysis of a two-body floating wave energy converter with particular focus on the effects of power take-off and mooring systems on energy capture. J Offshore Mech Arct 135(3):031902. https://doi.org/10.1115/1.4023796

Sinha A, Karmakar D, Soares CG (2016) Performance of optimally tuned arrays of heaving point absorbers. Renew Energy 92:517–531. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2016.02.043

Vicente PC, Falcão AF, Justino PA (2013) Nonlinear dynamics of a tightly moored point-absorber wave energy converter. Ocean Eng 59:20–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2012.12.008

Wu B, Wang X, Diao X, Peng W, Zhang Y (2014) Response and conversion efficiency of two degrees of freedom wave energy device. Ocean Eng 76:10–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oceaneng.2013.11.001

Yu Y, Yi H, Li Y (2013) Reynolds-Averaged Navier–Stokes simulation of the heave performance of a two-body floating-point absorber wave energy system. Comput Fluids 73:104–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compfluid.2012.10.007

Zhao J, Zhang L, Wu H (2012) Motion performance and mooring system of a floating offshore wind turbine. J Mar Sci Appl 11(3):328–334. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11804-012-1140-3

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Article Highlights

• Two types of mooring systems, which are tension leg mooring (TLM) and three-point taut mooring (TPM) systems, are applied to the model and compared their effect on the WEC model efficiency.

• The TLM system showed outstanding performance in increasing the relative heave displacement between the two bodies of the model compared to the TPM system.

• The effect of the TLM system on the absorbed power was more remarkable than that of the TPM system.

• The parameter of mooring lines stiffness can improve the hydrodynamic performance of the model and raise the absorption efficiency of the model compared to the pretension parameter of tendons.

Rights and permissions

OpenAccess This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Berenjkoob, M.N., Ghiasi, M. & Soares, C.G. Performance of Two Types of Mooring Systems in the Heave Motion of a Two-body Floating Wave Energy Converter. J. Marine. Sci. Appl. 18, 38–47 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11804-019-00082-w

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11804-019-00082-w