Abstract

Introduction

Obesity is a serious lifestyle disease with various comorbidities and an augmented risk of cancer. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) has recently become the most popular bariatric procedure worldwide. While the cost-effectiveness is a major healthcare providers’ concern, the point of histological exam of each resected tissue may be questioned.

Material/Methods

We prospectively included patients who underwent LSG. Before the surgery, gastroscopy and abdominal sonography were performed to exclude malignancies. The gastric specimen was cut open after the surgery and inspected macroscopically, then sent for a microscopic examination.

Results

In 5 cases out of 115, macroscopic evaluation of the resected specimen performed by the surgeon suggested existing pathology, confirmed by a microscopic evaluation in 3 out of 5 cases. In the remaining 2 cases, pathological analysis did not reveal abnormalities. In 110 cases, the gastric specimen was recognized to be unchanged by the surgeon, 109 out of which were confirmed by the pathologist to be normal, in 1 case a hyperplastic polyp was found. The sensitivity of macroscopic evaluation reached 75% (95% CI, 19.4–99.4%, p = 0.625), with specificity of 98.2% (95% CI, 93.6–99.8%, p < 0.0001), and negative predictive value of 99.1% (95% CI, 95–99.9%, p < 0.0001).

Conclusions

During LSG, a thorough visual inspection of the peritoneal cavity along with a macroscopic surgical evaluation of specimen in patients who had preoperative endoscopy with no findings allows to achieve very good specificity and good sensitivity. Therefore, this procedure may be useful as a screening test for incidental pathologies in bariatric patients and may exclude unnecessary histological examination.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Obesity is a serious lifestyle disease with various comorbidities and a higher than average risk of cancer [1,2,3,4]. As it is commonly known, bariatric surgery is the most effective way of treatment [5] and the annual number of bariatric procedures performed constantly increases, having reached 600,000 worldwide in 2014 [6]. This global trend is also observed on our national level, as reported by Janik et al. [7].

Bariatric techniques are constantly evolving with new concepts emerging. Laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy (LSG) has recently become the most popular procedure worldwide. As financial efficiency has become one of the healthcare providers’ major concerns, the point of histological exam of each resected tissue specimen can be questioned. The utility of histological examination of the resected macroscopically unchanged appendix, gallbladder or hemorrhoids is doubted by some of the authors [8, 9]. Therefore, we wanted to analyze whether bariatric specimens should be examined, also considering the recent publications about incidental findings after LSG [10, 11].

Neither national, nor international bariatric recommendations present the optimum strategy of proceeding with the gastric specimen resected during laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy.

Our aim was to evaluate whether manual macroscopic inspection of the gastric specimens is a useful tool to reveal incidental pathologies after LSG.

Material and Methods

We prospectively included all consecutive patients who had undergone LSG from January to August 2017 in our bariatric center. The patients were qualified for bariatric surgery according to the acknowledged international criteria [12]. A gastroscopy and abdominal sonography were routinely performed before the surgery, and patients with visible malignancies were excluded and qualified for detailed evaluation. Every procedure was performed by a bariatric surgeon according to the protocol described in our previous studies [13].

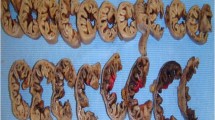

Peritoneal cavity was inspected after insulation. In the case of any suspicious findings in the peritoneal cavity, a biopsy was performed for further evaluation. After the surgery, each gastric specimen was cut open and macroscopically inspected by the surgeon. The evaluation included visual analysis and palpation, and the result was presented as suspected pathology or normal tissue. Then each specimen was sent for a microscopic examination performed by two pathologists. The microscopic examination was performed after chemical fixation and processing with an addition of immunohistochemistry staining if necessary. The medical diagnosis was formulated as a pathology report by two independent pathology specialists.

We gathered the data on patients’ age, BMI, and weight loss before the surgery as well as the results of the macro- and microscopic evaluations of the specimen.

Statistical analysis was performed using SAS software, University Edition (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). To compare continuous variables, the Mann-Whitney U test and Student’s t test were used when appropriate. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. The study was approved by the Bioethical Committee of the Warsaw Military Institute.

Results

Among 115 patients, 77 were female, the median age was 38 years (Q1, 31; Q3, 48). The mean BMI was 48.4 kg/m2 (± 8.4), and mean weight loss during the qualification process reached 10.6 kg (± 5). The mean length of hospital stay after the surgery was 2 days (± 0.3). Sixteen patients (13.91%) had previous history of peptic ulcers. Thirty-five (30.43%) patients admitted smoking (Table 1).

In five cases, macroscopic evaluation of the resected gastric specimen performed by the surgeon suggested existing pathology, which was confirmed by a microscopic evaluation by a pathologist in three out of five cases (two cases of hyperplastic polyps and one case of neuroendocrine microtumor). In the remaining two cases, pathological analysis did not reveal abnormalities in the gastric wall. In 110 cases, the gastric specimen was recognized to be unchanged by the surgeon, 109 out of which were confirmed by the pathologist to be normal, in one case the pathologist found a hyperplastic polyp. Summarizing, the results of the microscopic analysis were negative in 111 cases and positive in four cases (Table 2).

The sensitivity of the macroscopic surgical inspection reached 75% (95% CI, 19.4–99.4%, p = 0.625), with specificity of 98.2% (95% CI, 93.6–99.8%, p < 0.0001), and negative predictive value of 99.1% (95% CI, 95–99.9%, p < 0.0001) (Table 3).

The microscopic evaluation revealed gastritis in 50 specimens (43.48%), 61 (53.04%) had normal mucosa, and 4 cases presented pathologies: 3 cases of hyperplastic polyps (2.61%) and 1 neuroendocrine microtumor (0.09%) with two G1 neuroendocrine tumor (NET) foci, with proliferation index lower than 1%, mitotic index lower than 1 and high chromogranine and synaptophysin reaction, and diffused neuroendocrine hyperplasia with dysplasia in the rest of the mucosa.

Discussion

Bariatric surgery is a commonly accepted method of treatment of obesity when noninvasive methods are ineffective. Laparoscopic sleeve resection has recently become the most popular bariatric procedure worldwide.

Excess weight is proved to be a risk factor for malignancies and the incidence of gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) is much higher in the obese population [14]. When not diagnosed in time, GISTs can lead to poor outcomes as 40% up to 50% of patients may have relapse even after oncologically radical resection [15]. Healthcare professionals are still debating whether or not a surgical specimen should be evaluated microscopically if it does not come from an oncological procedure. In the case of laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy, the researchers present opposed approaches.

Hansen et al. [16] evaluated 351 tissue samples, not having revealed any pathologies, therefore concluding that a standard pathological examination is unnecessary. Having analyzed 546 microscopic results of gastric specimens, AbdullGaffar et al. [17] found four pathological cases (0.8%): two hyperplastic polyps, one cyst, and one benign tumor. Further investigation did not show any anomalies in patients, and the fact of positive findings did not increase the perioperative risk. Due to cost-effectiveness, the author suggested restraining from routine histopathological analysis of the tissue resected. Both authors agree that every resected gastric specimen should be evaluated by the surgeon macroscopically and by palpation, followed by a microscopic analysis in the case of positive findings.

On the contrary, Yardimci et al. [18] evaluated 755 specimens and found neoplasms in 4 (0.5%) cases. Canil et al. [19] analyzed 925 cases in a 5-year span with a 0.3% rate of neoplasms. Both authors state that both preoperative gastroscopy and postoperative pathological examination are crucial in the case of LSG. Similar conclusions are presented by Almazeedi et al. [20]. After having analyzed the histopathological results of 656 patients, he found 12 cases with abnormalities (1.8%). None of the researchers mentioned the sensitivity or specificity of the presented methods of evaluation of the resected gastric specimen after LSG.

Over the last few years, our team of researchers reviewed 1252 bariatric procedures performed over the course of 3 years [10, 11]. After laparoscopic visual evaluation during LSG, 50 specimens were qualified to further microscopic evaluation, revealing pathologies in 29 cases, with GISTs found in 16 cases. That may lead to the conclusion that GIST predominance is 1000 times higher among bariatric patients than in general population. We continued our research trying to create an optimal screening test, which would allow to select specimens for further evaluation. Introduction of such screening would reduce the cost of unnecessary routine histopathological exams. Our conclusions are similar to those presented by Gagner [21], who recommends surgical macroscopic evaluation of the specimens as standard after LSG. Every suspicion should be marked, described, and verified by the pathologist.

Any diagnostic test should have an acceptable sensitivity and specificity. Our method of macroscopic evaluation compared with microscopic histopathological examination revealed pathologies in 75% of cases and correctly identified unchanged specimen in 98.2% of cases. Our method also presented a high negative predictive value of 99.1%, which makes it usable as a screening test. The limitation of the study is a relatively low number of cases included so further studies with larger groups are necessary to evaluate the usefulness of the presented method.

Conclusion

During LSG, a thorough visual inspection of the peritoneal cavity along with a macroscopic surgical evaluation of the gastric specimen in patients who had preoperative endoscopy with no macroscopic findings allows to achieve very good specificity and good sensitivity. Therefore, this procedure may be useful as a screening test for incidental pathologies in bariatric patients and may exclude unnecessary histopathological examination of all surgical specimens after bariatric operations.

References

Landsberg L, Aronne LJ, Beilin LJ, et al. Obesity-related hypertension: pathogenesis, cardiovascular risk, and treatment—a position paper of the The Obesity Society and the American Society of Hypertension. Obesity. 2013;21:8–24. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23401272. Accessed 13 May 2018

Hartemink N, Boshuizen HC, Nagelkerke NJD, et al. Combining risk estimates from observational studies with different exposure cutpoints: a meta-analysis on body mass index and diabetes type 2. Am J Epidemiol. 2006;163:1042–52. Available from: http://academic.oup.com/aje/article/163/11/1042/168538/Combining-Risk-Estimates-from-Observational

Kaaks R, Lukanova A, Kurzer MS. Obesity, endogenous hormones, and endometrial cancer risk: a synthetic review. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2002;11:1531–43. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12496040

Guh DP, Zhang W, Bansback N, et al. The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:88. Available from: http://bmcpublichealth.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/1471-2458-9-88

Gloy VL, Briel M, Bhatt DL, et al. Bariatric surgery versus non-surgical treatment for obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2013;347:f5934. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/24149519

Angrisani L, Santonicola A, Iovino P, et al. Bariatric surgery and endoluminal procedures: IFSO worldwide survey 2014. Obes Surg. 2017;27:2279–89. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11695-017-2666-x

Janik MR, Stanowski E, Paśnik K. Present status of bariatric surgery in Poland. Videosurgery Other Miniinvasive Tech. 2016;1:22–5. Available from: http://www.termedia.pl/doi/10.5114/wiitm.2016.58742

Lohsiriwat V, Vongjirad A, Lohsiriwat D. Value of routine histopathologic examination of three common surgical specimens: appendix, gallbladder, and hemorrhoid. World J Surg. 2009;33:2189–93. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s00268-009-0164-6

Swank HA, Eshuis EJ, Ubbink DT, et al. Is routine histopathological examination of appendectomy specimens useful? A systematic review of the literature. Color Dis. 2011;13:1214–21. Available from: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/j.1463-1318.2010.02457.x

Walędziak M, Różańska-Walędziak A, Kowalewski PK, et al. Histopathological examination of tissue resected during bariatric procedures—to be done or not to be done? Videosurgery Other Miniinvasive Tech [Iinne Tech Małoinwazyjne]. 2017; https://doi.org/10.5114/wiitm.2017.67807.

Walędziak M, Różańska-Walędziak A, Kowalewski PK, et al. Bariatric surgery and incidental gastrointestinal stromal tumors—a single-center study. Videosurgery Other Miniinvasive Tech. 2017;3:325–9. Available from: https://www.termedia.pl/doi/10.5114/wiitm.2017.70215

Wyleżoł M, Paśnik K, Dąbrowiecki S, et al. Polish recommendations for bariatric surgery. Wideochirurgia iinne Tech małoinwazyjne/Videosurgery Other Miniinvasive Tech Suppl. 2009;4:8. Available from: http://www.termedia.pl/Polish-recommendations-for-bariatric-surgery,58,13376,1,1.html

Janik MR, Walędziak M, Brągoszewski J, et al. Prediction model for hemorrhagic complications after laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy: development of sleeve bleed calculator. Obes Surg. 2017;27:968–72.

Yuval JB, Khalaileh A, Abu-Gazala M, et al. The true incidence of gastric GIST—a study based on morbidly obese patients undergoing sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2014;24:2134–7.

Rutkowski P, Hompes D. Combined therapy of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Surg Oncol Clin N Am. 2016;25:735–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.soc.2016.05.006.

Hansen SK, Pottorf BJ, Hollis HW, et al. Is it necessary to perform full pathologic review of all gastric remnants following sleeve gastrectomy? Am J Surg. 2017;214:1151–5. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S0002961017304221

AbdullGaffar B, Raman L, Khamas A, et al. Should we abandon routine microscopic examination in bariatric sleeve gastrectomy specimens? Obes Surg. 2016;26:105–10.

Yardimci E, Bozkurt S, Baskoy L, et al. Rare entities of histopathological findings in 755 sleeve gastrectomy cases: a synopsis of preoperative endoscopy findings and histological evaluation of the specimen. Obes Surg. 2018;28:1289–95. Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11695-017-3014-x

Canil AM, Iossa A, Termine P, et al. Histopathology findings in patients undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. Obes Surg. 2018; Available from: http://link.springer.com/10.1007/s11695-017-3092-9

Almazeedi S, Al-Sabah S, Al-Mulla A, et al. Gastric histopathologies in patients undergoing laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomies. Obes Surg. 2013;23:314–9.

Gagner M. Comment on: gastric mesenchymal tumors as incidental findings during Roux-en-Y gastric bypass. Surg Obes Relat Dis. 2018;14:28–9. Available from: http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1550728917310122

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Ethical Statement

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Walędziak, M., Różańska-Walędziak, A., Janik, M.R. et al. Macroscopic Evaluation of Gastric Specimens After Laparoscopic Sleeve Gastrectomy—an Optimum Screening Test for Incidental Pathologies?. OBES SURG 29, 28–31 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-018-3485-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11695-018-3485-4