Abstract

This report in the journal Gruppe. Interaktion. Organisation. Zeitschrift für Angewandte Organisationspsychologie aims at presenting how the analysis of implicit and explicit communication in organizational interaction can advance our insights into and implications for these interactions for research and science. Communication is a central process in modern organizations. Especially recurring forms of interaction in organizations (e.g., meetings or appraisal interviews) are of great importance for personal and organizational success. In these interactions, the communication between the interacting organizational members has a decisive impact on the interactions’ course and outcomes (e.g., satisfaction with the interaction, performance during the interaction). Therefore, the aim of this paper is to present two aspects of communication that are empirically shown to contribute to successful outcomes of organizational interactions. Based on a practical problem, we illustrate the analysis and implications of (1) implicit communication (that is, the use and coordination of unconsciously used function words such as pronouns, articles, or prepositions) and (2) explicit communication (that is, the overarching meaning of a statement). To further illustrate the practical relevance of both communication behaviors, we present empirical insights and their implications for practice. Taking a glance at the future, possible combinations of these communication behaviors, the resulting avenues for future research, and the importance of a strengthened cooperation between research and practice to gain more naturalistic insights into organizational communication dynamics are discussed.

Zusammenfassung

Mit diesem Beitrag in der Zeitschrift Gruppe. Interaktion. Organisation. Zeitschrift für Angewandte Organisationspsychologie soll das Potenzial der Analyse von impliziter und expliziter Kommunikation in organisationalen Interaktionen dargestellt werden, um langfristig die Einblicke in und Handlungsempfehlungen aus organisationalen Kommunikationsdynamiken für Praxis und Wissenschaft auszubauen. Kommunikation stellt einen zentralen Prozess in modernen Organisationen dar. Vor allem wiederkehrende Formen der sozialen Interaktion in Organisationen (z. B., Meetings oder Mitarbeitergespräche) sind für den persönlichen und organisationalen Erfolg von großer Bedeutung. Gerade in diesen Interaktionen hat die Kommunikation der interagierenden Organisationsmitglieder entscheidende Auswirkungen auf den Verlauf sowie die Ergebnisse der Interaktion (z. B., Zufriedenheit mit der Interaktion, Leistung in der Interaktion). Ziel dieses Beitrages ist es daher, zwei Kommunikationsaspekte vorzustellen, die im Rahmen empirischer Forschung einen Einfluss auf den Erfolg organisationaler Interaktionen gezeigt haben. Ausgehend von einer praktischen Frage, werden die Analyse sowie mögliche Implikationen aus der Betrachtung von (1) impliziten Kommunikationsaspekten (d. h., die individuelle und simultane Äußerung von unbewusst genutzten Funktionsworten wie Pronomen, Artikeln und Präpositionen) sowie (2) expliziten Kommunikationsaspekten (d. h., die übergeordnete(n) Funktion(en) einer Aussage) erläutert. Um die praktische Relevanz zu verdeutlichen, werden empirische Ergebnisse und deren Implikationen für die Praxis dargestellt. Mit einem Blick in die Zukunft werden zudem Potenziale einer Kombination beider Formen der Kommunikationsaspekte diskutiert. Insgesamt soll dieser Beitrag die zukünftige Kooperation zwischen Forschung und Praxis weiter stärken, um tiefergehende Einblicke in natürliche organisationale Interaktionen zu erhalten und unser Verständnis dieser zu verbessern.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction: a practical problem

Ms. Flach leads the development department in a large tech company. Her team consists of 14 employees from various disciplines. In her position as a supervisor, Ms. Flach noticed one thing very early on: Everywhere in the organization, but also within her department, the communication between the employees seems to be the basis of all ongoing processes. Colleagues talk to each other when getting a coffee, supervisors hold structured appraisal interviews with their employees, team members discuss important topics in meetings. The importance of communication particularly strikes Ms. Flach when she directly interacts with her employees. To her, it seems that every interaction demands different communication behaviors which, in turn, have different effects depending on the employees she interacts with and the goal of the situation. For example, communication seems to be highly relevant in their regular team meetings: While some meetings result in satisfying solutions very quickly and efficiently, other meetings go round and round in circles, hardly producing any results. On the one hand, there seem to be rather explicit, observable communication behaviors, such as naming problems or solutions, that seem to affect the outcomes. However, on the other hand, she increasingly feels that there is more to communication than these directly observable communication behaviors. Implicit communication behaviors, like the specific words her team members use, also seem to affect these interactions. Overall, she asks herself to what extent both implicit and explicit communication behaviors in her meetings develop over time and contribute to their success? For Ms. Flach, a successful meeting is a meeting that both satisfies each of her team members and contributes to the success of the organization as represented by the team’s performance.

This example is intended to demonstrate that communication is an integral part of our work-life and the basis of most of our (social) processes at work. Taking a closer look at communication allows us to identify different communication behaviors that can systematically be analyzed using methods from the field of communication analysis to identify their dynamics and effect on the success or failure of organizational interactions.

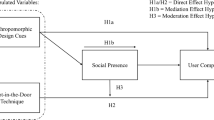

In line with Ms. Flach’s gut feeling, it is possible to distinguish between implicit and explicit communication. Implicit communication is represented by employees’ use of specific types of words, whereas explicit communication relates to the overarching meaning or function of communication (Weiss et al. 2018). The aim of this paper is to bring both forms of communication and their relevance for organizational interactions into the focus of practice. Therefore, we first provide a general introduction to both communication behaviors and their theoretical relevance. Using an example from a meeting of Ms. Flach’s team, we then illustrate how to analyze implicit and explicit communication behaviors. A special feature of the analysis of implicit and explicit communication behaviors presented in this article is that they take into account dynamic changes in communication over time and, thus, allow us to gain insights into the complex (social) dynamics of organizational communication that are hidden from the naked eye (e.g., Kozlowski 2015; Lehmann-Willenbrock and Allen 2018; Müller-Frommeyer et al. 2020). To further illustrate practical benefits, we present empirical insights and implications that can be drawn from the analysis of implicit as well as explicit communication behaviors. Lastly, we discuss how a combined analysis of implicit and explicit communication behaviors can open up new streams of research and provide us further practical insights in the future. Thus, we contribute to the existing literature by elaborating on the practical relevance of both forms of communication behaviors with the aim of increasing their application in real organizational interactions. In addition, we expand already existing knowledge by illustrating the potential of linking both approaches.

2 Implicit and explicit communication behaviors

Based on Ms. Flach’s observations in her daily interactions at work, we have already introduced the two forms of communications behaviors in focus of this article: Implicit and explicit communication. In the following, we outline their conceptual and theoretical differentiation in more detail. In previous research, both aspects of communication have been presented as highly relevant for the success of organizational interactions (e.g., Heuer et al. 2019; Meinecke et al. 2017; Weiss et al. 2018). A comparison of both communication behaviors can be found in Table 1. In general, communication is comprised of a variety of observable aspects: These range from words and their meaning to intonation, pitch, tempo, or nonverbal behaviors (Reynolds et al. 2015). If we focus on implicit and explicit communication behaviors, we will (almost) exclusively look at the verbal content of communication, more precisely at the use of words and their meaning. These allow us to gain insights into social and psychological aspects of communication (Tausczik and Pennebaker 2010) and remain intact in times of increasing virtual communication via virtual communication channels (e.g., email, chat; Cramton and Orvis 2003). However, despite these advantages, we acknowledge that we might not capture the full context of an interaction by (mainly) focusing on the verbal context.

Implicit communication behaviors focus on individual and mutual use of specific types of words. Since the early 2000s, advances in computerized text analysis—the computer-aided automatic analysis and quantification of texts—psychological research has focused on one type of words in particular: Function words such as pronouns, articles, or prepositions. Function words provide us insights into the social and psychological processes of an individual or interacting partners (Chung and Pennebaker 2007; Pennebaker et al. 2003; Tausczik and Pennebaker 2010). Since they are used unconsciously—and thus cannot be influenced—but still account for up to 60% of words used in everyday life (Segalowitz and Lane 2004; Van Gelderen 2014), the study of function words allows us to gain insight into implicit individual and collective communication dynamics. The individual use of function words has traditionally been method-driven (Tausczik and Pennebaker 2010). Only with the recent connection to the Dynamic Systems Theory (Abraham et al. 1990), Müller-Frommeyer et al. (2020) introduced a theoretical perspective. This perspective states that the individual use of function words can develop and change over time depending on contextual factors (e.g., the interaction partner or the type of conversation). With reference to Ms. Flach’s example, this means that any type of conversation in her professional life (e.g., meeting, appraisal interview, or conflict conversation) as well as the respective interaction partner(s) influences her individual use of function words. Since the individual use of function words is also referred to as individual language style which represents how people communicate rather than what they say, Ms. Flach’s function word use can impact her employees and interactions (Weiss et al. 2018).

In (organizational) interactions a coordination of function words, that is, a similar use of function words over time, can be observed (e.g., Pennebaker et al. 2003; Ireland and Pennebaker 2010; Ireland et al. 2011). This form of function word coordination is also called language style matching. Theoretically, language style matching can be explained under the interpersonal synergy framework. Under this framework, coordination processes are an essential part of all forms of social interactions, occur unconsciously, and impact the interaction partners as well as outcomes of the interaction depending on its context and/or goal(s) (e.g., Müller-Frommeyer et al. 2019; Riley et al. 2011). Here, goals can both represent external, shared goals that are, for example, provided by the company management in an organization, or more implicit individual goals that develop throughout the interaction. A collective use of function words—representing a synchronized style of speaking—indicates a common understanding and worldview (Brennan and Hanna 2009). In relation to Ms. Flach’s team meetings this means that the team members coordinate their implicit communication in the form of function word use depending on its context or goal in order to achieve their respective goals. Depending on the current goal of the meeting, however, this coordination can develop differently—that is, employees use their function words more or less interdependently—which can have positive and negative effects on the interacting team members and the success of the meeting. Taken together, when investigating the effect of implicit communication behaviors in Ms. Flach’s team meetings, we could (1) assess Ms. Flach’s individual use of function words as team leader and (2) the coordination of function words in the team meeting in relation to her two major outcomes of interest: Meeting satisfaction and team performance.

In contrast to implicit communication, explicit communication focusses on the overarching meaning or function of a statement, sentence, or parts of the sentence and potentially considers more aspects of communication than the individual words used (e.g., the accompanying intonation, pitch, or nonverbal behaviors). In this article, we focus on explicit communication that either constitutes a structural (e.g., coherence, coordination) or functional (e.g., problem-solving behaviors, knowledge transfer) contribution to communication. Theoretically, explicit communication can be regarded as a process that contributes to the outcome of an interaction (e.g., Ilgen et al. 2005; McGrath and Altermatt 2001). According to McGrath and Altermatt (2001), processes encompass the simultaneous and sequential behavior of the interacting individuals while they act in relation to each other and to the task and its goal. Refering back to Ms. Flach’s example, we could look at the communication behaviors of interest (that is, the simultaneous or sequential stating of solutions or problems) and their relation to satisfaction or team performance.

3 Analyzing implicit and explicit communication behaviors

After providing an overview over the conceptual and theoretical differentiation between implicit and explicit communication behaviors in relation to Ms. Flach’s example, we go one step further and demonstrate the analysis of both forms of communication behaviors. We do this with the help of a (fictious) meeting of Ms. Flach’s team. A transcribed excerpt of this meeting can be found in Table 2. Inspired by Ms. Flach’s practical concerns, we explore implicit and explicit communication behaviors in a natural organizational interaction. Investigating this form of interaction is not only advantageous to Ms. Flach but offers a great advantage for research as well: By exploring communication dynamics in real-life organizational interactions, researchers can achieve highest external validity—that is, they are able to generalize the results of a scientific study to the organizational context.

Traditionally, real-life interactions are either manually observed or recorded using video or audio recorders. With the rise of virtual collaborations in organizations, the use of information communication technology (e.g., email, chat) provides the opportunity to collect written samples of organizational communication, and thus, access to even more unobtrusive possibilities of generating organizational communication data. As the recorded communication by definition contains personal and potentially sensitive information, it is highly important to always follow data security protocols, to assure voluntary consent to being recorded, anonymity to the interacting employees, and often also the consent of the works council.

3.1 Analyzing implicit communication

In the following, we provide a short explanation of the steps necessary to extract implicit communication in the form of individual and collective function word use from natural organizational interactions.

3.1.1 Step 1: Transcribing your interactions

The basis for the analysis of implicit communication is the word-for-word transcription of the recorded organizational interaction (please see Müller-Frommeyer et al. (2019) for more information on the transcription of natural language). It is advisable to clearly mark each speaker during the transcription process. When working with protocols of written verbal interactions (e.g., from virtual communication), reassure the chronological order of these interactions for the accurate assessment of their dynamics.

3.1.2 Step 2: Identifying function words

Even though, the classification of words used in organizational interactions could be done manually (e.g., by identifying pronouns, articles, or prepositions), there are validated software solutions that facilitate and speed up the process a lot. The software most prominent in psychological research is called Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC; Pennebaker et al. 2015). LIWC counts the words in a transcript and compares them against a built-in dictionary. For example, the current version of the English dictionary contains more than 18,000 words which are assigned to one or more of 77 non-exclusive categories. The LIWC dictionary is organized into four main themes: basic linguistic processes (e.g., function words), psychological processes (e.g., positive emotion, negative emotion), personal concerns (e.g., family, friends), and spoken categories (e.g., swear words, assent) (Pennebaker et al. 2015). As indicated above, function words fall into the theme of basic linguistic processes and comprise the categories pronouns, articles, prepositions, auxiliary verbs, common adverbs, conjunctions, and negations. Using LIWC allows to parse units from single words to complete conversations into psychologically relevant dimensions accurately and quickly (Gonzales et al. 2010). LIWC reports the proportion of words that fall into a chosen category in the unit under analysis (e.g., the proportion of function words in a whole text, a statement, or a sentence). These proportions can be exported and used for further analyses (e.g., Ireland et al. 2011; Müller-Frommeyer et al. 2019). LIWC is available and comprehensively validated for both German and English (e.g., Meier et al. 2018).

3.1.3 Assessing implicit communication dynamics

To gain deeper insights into implicit communication dynamics, that is, to assess the individual dynamics of function word use or language style matching, further treatment of the LIWC results is necessary. One option is to assess the dynamics of individual function word use over time (cf. Müller-Frommeyer et al. 2020). This might uncover changes in function word use triggered by external factors and their effect on the interaction and interaction partners.

Language style matching is calculated using a weighed difference score that includes the proportion of function word use from LIWC analysis (e.g., Heuer et al. 2019; Ireland and Pennebaker 2010; Müller-Frommeyer et al. 2019). Language style matching scores can take values between 0 and 1, where a score of 0 represents no language style matching whereas a score of 1 represents high language style matching (Niederhoffer and Pennebaker 2002). There are resources available that support the calculation of language style matching for dyadic (Müller-Frommeyer et al. 2019) as well as group/team settings which consider the temporal dynamics of function word use over time. While the literature on language style matching specifically works with function words, the procedure can theoretically be transferred to assess coordination of other types of words as well (e.g., affect words to assess emotional contagion; Paulsen and Kauffeld 2016).

3.2 Analyzing explicit communication behaviors

To analyze explicit communication, traditional qualitative interaction analysis is used (e.g., Meinecke and Kauffeld 2016; Brauner et al. 2018). We give a brief overview of the process of analyzing explicit communication specifically focusing on Ms. Flach’s team meeting.

3.2.1 Step 1: Defining the explicit communication behavior of interest

Prior to starting your data collection, the phenomenon of interest—that is, the explicit communication behavior you want to assess—needs to be defined. This is necessary to determine the form of interaction that needs to be investigated.

3.2.2 Step 2: Choosing/Developing a coding scheme

The analysis of explicit communication is based on coding the collected data using a coding scheme that allows you to answer your specific research question/hypothesis by assessing your previously defined communication behaviors of interest. For example, as Ms. Flach is interested in how naming solutions and problems is related to meeting satisfaction and team performance, Ms. Flach needs a coding scheme that explicitly incorporates these two communication behaviors. There is a variety of established coding schemes available to investigate communication in different social and organizational settings—Table 3 provides a selection of established coding schemes that allow you to assess different structural (e.g., coherence, coordination) and functional (e.g., problem-solving behaviors, knowledge transfer) aspects of communication. Table 3 aims at illustrating that (1) there is already a multiplicity of established coding schemes available and (2) potential research questions for their application. However, in this paper we only take a more detailed look at one of the coding schemes and apply it to Ms. Flach’s meeting. What these established coding schemes have in common is that they allow you to objectively assign pre-defined codes to the recorded data (for example, the statement We are way behind our current deadline. is assigned the code Problem in the act4teams coding scheme). As indicated above, behavioral indicators for these codes rely mainly on the verbal content of a message but might also include other aspects of communication like intonation, pitch, or nonverbal behaviors. Additionally, most established coding schemes provide guidelines on how to sequence the communication in your data. Sequencing your data results in successive sense units, each of which can be assigned its own communicative function. Usually, codes are assigned to the smallest unit to which a unique function can be assigned (e.g., a single word; Bales 1950). However, if there is no established coding scheme for your specific research question, there is also the possibility to develop your own coding scheme (see Bakeman and Quera (2011) and/or Yoder and Symons (2010) for guidelines on the development of coding schemes). Developing a valid and reliable coding scheme, that is, one that measures the defined aspects of communication in a recurring manner, is a complex procedure. Besides the creation of codes and their precise definition and differentiation including illustrative examples, sequencing or cutting rules have to be defined. Only when the inter-rater reliability—that is, the statistical agreement between at least two independent coders who apply the coding system to the same section of communication—exceeds 80% (e.g. Cohen’s Kappa, Cohen 1960), a newly developed coding system meets these requirements.

3.2.3 Step 3: Coding your data

Once the coding scheme is chosen/developed and the sequencing rules are defined, the communication data is coded. The coding itself is usually done by coders who received extensive training for the coding scheme to ensure objectivity, comparability, and generalizability of the results. Using available software solutions can facilitate the coding process and subsequent data analysis. Several software solutions—licensed as well as open-source—are available that support the coding process (e.g., INTERACT by Mangold 2014; Observer XT by Zimmermann et al. 2009; CASAA Application for Coding Treatment Interactions (CACTI) by Glynn et al. 2012). Using software in the coding process allows you to unitize the data, assign the relevant code to each unit and export the data for further statistical analysis.

4 Implications from implicit and explicit communication behaviors

Now Ms. Flach knows that she can systematically differentiate between implicit and explicit communication behaviors that occur during her interactions at work and has an idea of how to conduct the analysis, she is still wondering about the implications she can draw from these analysis. We will illustrate results and potential implications from Ms. Flach’s team meeting and complement these by empirical findings.

4.1 Implicit communication behaviors in Ms. Flach’s meeting

For Ms. Flach’s team meeting, we take a look at (1) the use of function words to assess overall language style, and (2) language style matching as an indicator of a common understanding. The results are displayed in Table 2.

Looking at function word use across the excerpt, we see that the statements contain between 46 and 57% function words. This is representative of general function word use as they account for up to 60% of the words we use (Pennebaker 2013). When further considering the language style matching in the meeting, we see that with a mean score of M = 0.95, language style matching scores can be classified as high. Taking a closer look at the temporal sequence of language style matching, it is still striking that with scores ≥ 0.89 language style matching is high over the course of this excerpt. Following our explanation of language style matching, this might be indicative of a shared worldview—in this short excerpt of the meeting, the team members linguistically relate to each other and seem to have a shared understanding of the conversational content (Brennan and Hanna 2009).

If we were further interested in analyzing the relationship to the outcomes of interest, that is, meeting satisfaction and team performance, we would also need to further collect indicators of both criteria. Meeting satisfaction could be assessed via postmeeting questionnaires completed by each team member, whereas team performance could be indicated by objective productivity data from the respective team (cf. Kauffeld and Lehmann-Willenbrock 2012). For Ms. Flach, an analysis of the relationship between (1) her personal use of implicit communication behaviors, and (2) overall language style matching within the team in relationship to the two outcomes could indicate the importance of these communication behaviors for individual and organizational indicators of success.

4.2 Drawing conclusions from implicit communication behaviors for practice

The assessment of implicit communication behaviors can inform us about ongoing processes in the interaction. Putting the proportion of function words used in organizational interaction into relation to relevant outcome criteria (e.g., team performance), might provide practical implications on which kind of language to support or avoid. For example, leaders’ use of the First-Person Plural Pronoun we encourages their team members to speak up in interdisciplinary teams (Weiss et al. 2018).

Additionally, language style matching analyses allow us further insights into the communication dynamics of these interactions. From the current state of research, we know that—depending on the context and goal of the interaction (Riley et al. 2011)—language style matching can have both positive and negative effects on interactions (Heuer et al. 2019). For example, Heuer et al. (2019) showed that language style matching during team meetings is positively related to perceived social support, whereas it is negatively related to team performance. These results indicate that to fully understand the dynamics of teams, it is important to also assess the way team members communicate. Furthermore, in annual appraisal interviews, Meinecke and Kauffeld (2019) showed that language style matching is positively related to supervisor’s empathic communication style. With empathic communication style being a predictor of employees’ intentions to change and perceptions of supervisor likeability (Meinecke and Kauffeld 2019), the insights into the implicit behavioral manifestations of leader empathy provides us new starting points to convey empathic communication in practice.

These results demonstrate the great potential of analyzing implicit aspects of communication for organizational practice: They can provide explanations for the emergence of established success criteria of organizational interactions (e.g., empathy; shared mental models; Meinecke and Kauffeld 2019; Yilmaz 2016). Even though, some of these insights do not yield direct guidelines for practitioners, advancing our understanding of communication dynamics in different forms of organizational interactions eventually will. However, more research assessing natural organizational interaction needs to be conducted to fully determine this potential.

4.3 Explicit communication behaviors in Ms. Flach’s meeting

While looking for established coding schemes that include Ms. Flach’s communication behaviors of interest (i.e., problems and solutions), Ms. Flach comes across a coding scheme called act4teams (Kauffeld 2006; Kauffeld and Lehmann-Willenbrock 2012). Act4teams was developed to measure naturally occurring interactions in organizational work groups and has widely been used to analyze video data from organizational meetings (e.g., Estel et al. 2019; Kauffeld and Lehmann-Willenbrock 2012; Lehmann-Willenbrock et al. 2017). Due to the wide range of previous applications, a focus on verbal expressions and a high level of detail with a total of 43 categories (see Kauffeld et al. (2018) for a detailed overview), Ms. Flach chooses to use act4teams to further investigate explicit communication in her meeting.

Ms. Flach commissioned experienced coders to code her meetings using act4teams. An overview of the codes can be found in Table 2. In this excerpt the team members’ statements fall into only four act4teams codes: question, problem (i.e., naming a problem), procedural suggestion (i.e., proposing the way forward) and solution (i.e., naming a solution). In this short excerpt, we can already observe some interesting aspects: Looking at the frequency of codes used, we see that the code used most often is problem (3), followed by solution (2), question (1), and procedural suggestion (1). Taking a closer look at the sequences of codes, we see that after an introductory question, a team member names a problem followed by two more team members naming problems. Only after a procedural suggestion, the team members start uttering solutions instead of problems.

Even if the results described here are exclusively descriptive in nature, they hint us towards a couple of important things: (1) The frequency of codes during an interaction already gives us insights into the communication that took place. (2) If we additionally consider the sequences of codes by applying adequate statistical methods that are able to identify communication patterns that emerge above chance (e.g., lag sequential analysis in e.g., Kauffeld and Meyers 2009; Lehmann-Willenbrock et al. 2017), we can learn about behavioral dependencies in organizational interaction. Here, it seems that naming a problem encourages others to name more problems and that procedural suggestions might elicit problem solving. Other forms of analysis can identify team roles in meetings (cf. Lehmann-Willenbrock et al. 2015) or different meeting phases and transitions between these (cf. Meinecke et al. 2016b).

4.4 Drawing conclusions from explicit communication behaviors for practice

The analysis of explicit communication behaviors allows us to gain various insights into the communication dynamics of organizational interactions. On the one hand, the descriptive examination of the coded communication data already allows an overview the communication behaviors that are used. When put into relation to relevant outcome criteria—for example, meeting satisfaction or team performance in Ms. Flach’s case—the analysis of explicit communication behaviors can provide us interesting insights into communication behaviors that should be promoted or avoided. Empirical insights tell us that functional communication (e.g., solution-focused, positive participation-oriented statements) in meetings leads to higher meeting satisfaction (Kauffeld and Lehmann-Willenbrock 2012). With these effects being stable for short- and long-term meeting success (that is, immediately to 2.5 years after the meeting), they imply that successful meetings directly influence organizational success. As dysfunctional communication (e.g., getting lost in details and examples, gossip/devaluation) has a profoundly negative influence on meeting success, it should be avoided or at least be limited to a reasonable proportion (Kauffeld and Lehmann-Willenbrock 2012). In addition, positivity in meetings—represented by statements that are constructive in intention or attitude, showing optimism and confidence—is positively related to team performance (Lehmann-Willenbrock et al. 2017). For appraisal interviews, we see that supervisor’s relation-oriented statements (e.g., verbal encouraging, active listening) are related to higher interview success ratings by both supervisors and employees (Meinecke et al. 2017) further supporting the existing claim that supervisors need to invite their employees to participate in the appraisal interview.

If, in addition, statistical analyses are applied that consider more than only one interaction and try to find sequences and patterns in the data, more concealed communication dynamics can be uncovered to derive implications for successful interactions in organizations. From empirical research, we already know that dysfunctional meeting behaviors in the form of complaining significantly increase the chances of more complaining (leading to so-called complaining circles), simultaneously inhibiting the chances of showing solution-oriented behaviors (Kauffeld 2007). Functional behavior in the form of solution-oriented statements, on the other hand, entails further solution-oriented statements and significantly decreases the probability of complaining (Kauffeld 2007). Turning to appraisal interviews, we see that supervisors use of relation-oriented statements as compared to task-oriented statements (e.g., performance evaluation, knowledge management) elicits employee participation, and vice versa (Meinecke et al. 2016b, 2017).

5 A glance into the future: Combining implicit and explicit analysis

In previous research, both implicit and explicit communication behaviors have been presented as relevant for organizational practice (e.g., Kauffeld and Lehmann-Willenbrock 2012; Meinecke and Kauffeld 2019; Weiss et al. 2018). While analyzing implicit communication behaviors helps us to understand how the way we communicate can influence organizational interactions, analyzing explicit communication behaviors often provides direct guidelines for practice. Looking into the future, it is precisely this circumstance that conceals further potential: By investigating the extent to which explicit communication behaviors are accompanied by implicit communication behaviors, a combination of the two approaches opens avenues for new insights. If we take meetings as an example, we could explore if functional communication is accompanied by high language style matching, while more dysfunctional communication is accompanied by low language style matching? And does this have the same effect on the success of the meeting?

At the same time, it would be exciting to investigate what effects deviations in implicit and explicit processes have: What happens when language style matching is low but explicit communication behaviors are still functional? What influence does such a circumstance have on the interacting partners—for example, do implicit communication behaviors like low language style matching trigger distrust even though the interaction appears to be positive?

Last but not least, the combination of the methods allows for further analysis implicit communication behaviors as indicators of explicit communication behaviors or even emergent phenomena occurring over the process of the interaction (e.g., team mental models, trust; Kozlowski 2015; Yilmaz 2016). Many of these emergent phenomena have a positive impact on organizational interactions—therefore, assessing which behavioral processes contribute to their emergence would advance our understanding significantly.

6 Conclusion

Investigating implicit and explicit communication behaviors in organizational interaction allows us to investigate aspects and dynamics of communication that would otherwise remain hidden. Implicit communication behaviors allow us insights into deeper, often nonconscious aspects of language production, while explicit communication behaviors allow us to assess patterns and dynamics of consciously used and trainable communication behaviors. Especially the analysis of implicit communication behavior has not yet reached the focus of organizational sciences. Apart from the empirical insights already mentioned in this article, concrete starting points for practice are still scarce. The reasons for this are not yet clearly stated. Since implicit communication behaviors are often unconsciously used and therefore not trainable, it is conceivable that the limited derivation of direct practical implications may limit organizational interest to date. However, the theoretical and empirical results presented in this article (e.g., Heuer et al. 2019; Meinecke and Kauffeld 2019; Weiss et al. 2018) illustrate that this approach offers enormous potential for understanding organizational communication dynamics and their impact on success indicators. With recent developments in research on implicit communication behaviors that allow for a consideration of implicit communication dynamics over time as a function of context factors determined by the organization (e.g., task, goal, team composition) (cf. Müller-Frommeyer et al. 2019, 2020; Müller-Frommeyer and Kauffeld in preparation), intensive further research can realize the potential of implicit communication behavior in a timely manner. Overall, the insights into communication dynamics will allow us to derive practical implications for various forms of organizational interaction. Thus, with an adequate application of the techniques presented here, individual satisfaction with the interaction situations, the success of these interaction situations and overall organizational success can be influenced positively.

One question that could potentially arise in this context is whether such a detailed, scientifically based analysis of organizational interactions is always necessary or whether the mere knowledge of beneficial or detrimental behaviors can already advance practice. The answer from a scientific perspective is: Knowledge about beneficial and harmful behaviors can be helpful, but only objective analysis of entire interaction situations from trained professionals can provide a comprehensive insight and derive reliable implications for specific questions and interactions. To do this a strong cooperation between science and practice is needed that further strengthens the collection of naturalistic organizational data and their translation into practical bitesize implication to establish relevant benchmarks.

However, to date, the investigation of implicit and explicit communication behaviors in naturalistic organizational settings is still relatively scarce which limits the insights that both researchers and practitioners have into organizational communication and thereby potential implications for their optimization. With this paper, we hope to encourage researchers and practitioners alike to apply assess both aspects of communication in organizational contexts. Technological advances such as automating the transcription process or automating the assignment of words to categories have already made its application a lot more feasible. Taking a look into the future, the application of machine learning might also facilitate the sometimes tedious process of applying coding schemes, allowing for the analysis of much larger amounts of data or even real-time coding of ongoing team meetings and automated hints for improving it to make it a success. A potential combination of both forms in the future will further shed light in the interplay between implicit and explicit aspects of communication.

References

Abraham, F. D., Abraham, R. H., & Shaw, C. D. (1990). A visual introduction to dynamical systems theoryfor psychology. Santa Cruz: Aerial.

Bakeman, R., & Quera, V. (2011). Sequential analysis and observational methods for the behavioral sciences. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bales, R. F. (1950). Interaction process analysis: a method for the study of small groups. Cambridge: Addison-Wesley.

Boos, M. (2018). CoCo: a category system for coding coherence in conversations. In E. Brauner, M. Boos & M. Kolbe (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of group interaction analysis (pp. 502–509). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Boos, M., & Sommer, C. (2018). ARGUMENT: a category system for analyzing argumentation in group discussions. In E. Brauner, M. Boos & M. Kolbe (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of group interaction analysis (pp. 460–466). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brauner, E. (2006). Kodierung transaktiver Wissensprozesse (TRAWIS). Zeitschrift für Sozialpsychologie, 37(2), 99–112. https://doi.org/10.1024/0044-3514.37.2.99.

Brauner, E., Boos, M., & Kolbe, M. (Eds.). (2018). The Cambridge handbook of group interaction analysis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brennan, S. E., & Hanna, J. E. (2009). Partner-specific adaptation in dialog. Topics in Cognitive Science, 1(2), 274–291. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1756-8765.2009.01019.x.

Chung, C., & Pennebaker, J. (2007). The psychological functions of function words. Social Communication. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203837702.

Cohen, J. (1960). A coefficient of agreement for nominal scales. Educational & Psychological Measurement, 20, 37–46.

Cramton, C. D., & Orvis, K. L. (2003). Overcoming barriers to information sharing in virtual teams. In C. B. Gibson & S. G. Cohen (Eds.), Virtual teams that work: Creating conditions for virtual team effectiveness (pp. 214–230). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Estel, V., Schulte, E. M., Spurk, D., & Kauffeld, S. (2019). LMX differentiation is good for some and bad for others: a multilevel analysis of effects of LMX differentiation in innovation teams. Cogent Psychology, 6(1), 1614306. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2019.1614306.

Glynn, L. H., Hallgren, K. A., Houck, J. M., & Moyers, T. B. (2012). Cacti: free, open-source software for the sequential coding of behavioral interactions. PLoS ONE. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0039740.

Gonzales, A. L., Hancock, J. T., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2010). Language style matching as a predictor of social dynamics in small groups. Communication Research, 37(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093650209351468.

Heuer, K., Müller-Frommeyer, L. C., & Kauffeld, S. (2019). Language matters: the double-edged role of linguistic style matching in work groups. Small Group Research, 51(2), 208–228. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496419874498.

Ilgen, D. R., Hollenbeck, J. R., Johnson, M., & Jundt, D. (2005). Teams in organizations: from input-process-output models to IMOI models. Annual Review of Psychology, 56, 517–543. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070250.

Ireland, M. E., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2010). Language style matching in writing: synchrony in essays, correspondence, and poetry. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 99(3), 549–571. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020386.

Ireland, M. E., Slatcher, R. B., Eastwick, P. W., Scissors, L. E., Finkel, E. J., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2011). Language style matching predicts relationship initiation and stability. Psychological Science, 22(1), 39–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610392928.

Kauffeld, S. (2006). Kompetenzen messen, bewerten, entwickeln. Stuttgart: Schäffer-Poeschel.

Kauffeld, S. (2007). Jammern oder Lösungsexploration Eine Sequenzanalytische Betrachtung des Interaktionsprozesses in betrieblichen Gruppen bei der Bewältigung von Optimierungsaufgaben. Zeitschrift für Arbeits- und Organisationspsychologie, 51(2), 55–67. https://doi.org/10.1026/0932-4089.51.2.55.

Kauffeld, S., & Lehmann-Willenbrock, N. (2012). Meetings matter: effects of team meetings on team and organizational success. Small Group Research, 43(2), 130–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/1046496411429599.

Kauffeld, S., & Meyers, R. A. (2009). Complaint and solution-oriented circles: interaction patterns in work group discussions. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 18(3), 267–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/13594320701693209.

Kauffeld, S., Lehmann-Willenbrock, N., & Meinecke, A. L. (2018). The Advanced Interaction Analysis for Teams (act4teams) coding scheme. In E. Brauner, M. Boos & M. Kolbe (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of group interaction analysis (pp. 422–431). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kolbe, M., Strack, M., Stein, A., & Boos, M. (2011). Effective coordination in human group decision making: MICRO-CO: a micro-analytical taxonomy for analysing explicit coordination mechanisms in decision-making groups. In M. Boos, M. Kolbe, P. M. Kappeler & T. Ellwart (Eds.), Coordination in human and primate groups (pp. 199–219). Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

Kozlowski, S. W. J. (2015). Advancing research on team process dynamics: theoretical, methodological, and measurement considerations. Organizational Psychology Review, 5(4), 270–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/2041386614533586.

Lehmann-Willenbrock, N., & Allen, J. A. (2018). Modeling temporal interaction dynamics in organizational settings. Journal of Business and Psychology, 33(3), 325–344. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-017-9506-9.

Lehmann-Willenbrock, N., Chiu, M. M., Lei, Z., & Kauffeld, S. (2017). Understanding positivity within dynamic team interactions: a statistical discourse analysis. Group and Organization Management, 42(1), 39–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601116628720.

Lehmann-Willenbrock, N., Meinecke, A. L., Rowold, J., & Kauffeld, S. (2015). How transformational leadership works during team interactions: a behavioral process analysis. Leadership Quarterly, 26(6), 1017–1033. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2015.07.003.

Mangold International (2014). INTERACT Benutzerhandbuch. Arnstorf: Mangold International. www.mangold-international.com

McGrath, J. E., & Altermatt, T. W. (2001). Observation and interaction over time: some methodological and strategic choices. In M. A. Hogg & S. Tindale (Eds.), Blackwell handbook of social psychology: group processes (pp. 525–556). Oxford: Blackwell.

Meier, T., Boyd, R. L., Pennebaker, J. W., Mehl, M. R., Martin, M., Wolf, M., & Horn, A. B. (2018). “LIWC auf Deutsch”: The development, pychometrics, and introduction of DE-LIWC2015. https://osf.io/tfqzc/. Accessed 19 Jan 2021.

Meinecke, A. L., & Kauffeld, S. (2016). Interaktionsanalyse in Gruppen: Anwendung und Herausforderungen. Gruppe. Interaktion. Organisation. Zeitschrift Fur Angewandte Organisationspsychologie, 47(4), 321–333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11612-016-0347-1.

Meinecke, A. L., & Kauffeld, S. (2019). Engaging the hearts and minds of followers: leader empathy and language style matching during appraisal interviews. Journal of Business and Psychology, 34(4), 485–501. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-018-9554-9.

Meinecke, A. L., Klonek, F. E., & Kauffeld, S. (2016a). Using observational research methods to study voice and silence in organizations. German Journal of Human Resource Management, 30(3/4), 195–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/2397002216649862.

Meinecke, A. L., Klonek, F. E., & Kauffeld, S. (2016b). Appraisal participation and perceived voice in annual appraisal interviews: uncovering contextual factors. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/1548051816655990.

Meinecke, A. L., Lehmann-Willenbrock, N., & Kauffeld, S. (2017). What happens during annual appraisal interviews? How leader-follower interactions unfold and impact interview outcomes. Journal of Applied Psychology, 102(7), 1054–1074. https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000219.

Moyers, T. B., Rowell, L. N., Manuel, J. K., Ernst, D., & Houck, J. M. (2016). The motivational interviewing treatment integrity code (MITI 4): rationale, preliminary reliability and validity. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 65, 36–42. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2016.01.001.

Müller-Frommeyer, L. C., Frommeyer, N. A. M., & Kauffeld, S. (2019). Introducing rLSM: an integrated metric assessing temporal reciprocity in language style matching. Behavior Research Methods, 51(3), 1343–1359. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-018-1078-8.

Müller-Frommeyer, L. C., Kauffeld, S., & Paxton, A. (2020). Beyond consistency: contextual dependency of language style in monolog and conversation. Cognitive Science. https://doi.org/10.1111/cogs.12834.

Niederhoffer, K. G., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2002). Linguistic style matching in social interaction. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 21(4), 337–360+454. https://doi.org/10.1177/026192702237953.

Paulsen, H. F. K., & Kauffeld, S. (2016). Ansteckungsprozesse in Gruppen: Die Rolle von geteilten Gefühlen für Gruppenprozesse und -ergebnisse. Gruppe. Interaktion. Organisation. Zeitschrift für angewandte Organisationspsychologie, 47(4), 357–364. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11612-016-0340-8.

Pennebaker, J. W. (2013). The secret life of pronouns—What our words say about us. New York: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Pennebaker, J. W., Boyd, R. L., Jordan, K., & Blackburn, K. (2015). The development and psychometric properties of LIWC2015. https://doi.org/10.1068/d010163.

Pennebaker, J. W., Mehl, M. R., & Niederhoffer, K. G. (2003). Psychological aspects of natural language use: our words, our selves. Annual Review of Psychology, 54(1), 547–577. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145041.

Reynolds, R., Mirot, A. J., & Nudze, P. D. (2015). Measuring shared mental models in unmanned aircraft systems. In M. Khosrow-Pour (Ed.), Encyclopedia of information science and technology (3rd edn., pp. 1188–1196). Hershey: IGI Global.

Riley, M. A., Richardson, M. J., Shockley, K., & Ramenzoni, V. C. (2011). Interpersonal synergies. Frontiers in Psychology, 2, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2011.00038.

Schermuly, C. C., Schröder, T., Nachtwei, J., & Scholl, W. (2010). Das Instrument zur Kodierung von Diskussionen (IKD): Ein Verfahren zur zeitökonomischen und validen Kodierung von Interaktionen in Organisationen. Zeitschrift für Arbeits- und Organisationspsychologie, 54(4), 149–170. https://doi.org/10.1026/0932-4089/a000026.

Segalowitz, S. J., & Lane, K. (2004). Preceptual fluency and lexical access for function versus content words. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 27(2), 307–308.

Tausczik, Y. R., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2010). The psychological meaning of words: LIWC and computerized text analysis methods. Journal of language and social psychology, 29(1), 24–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X09351676.

Van Gelderen, E. (2014). A history of the English language. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Weiss, M., Kolbe, M., Grote, G., Spahn, D. R., & Grande, B. (2018). We can do it! Inclusive leader language promotes voice behavior in multi-professional teams. Leadership Quarterly, 29(3), 389–402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2017.09.002.

Yilmaz, G. (2016). What you do and how you speak matter: behavioral and linguistic determinants of performance in virtual teams. Journal of Language and Social Psychology, 35(1), 76–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261927X15575772.

Yoder, P., & Symons, F. (2010). Observational measurement of behavior. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Müller-Frommeyer, L.C., Kauffeld, S. Gaining insights into organizational communication dynamics through the analysis of implicit and explicit communication. Gr Interakt Org 52, 173–183 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11612-021-00559-9

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11612-021-00559-9

Keywords

- Implicit communication

- Explicit communication

- Communication dynamics

- Language style matching

- Organizational interaction