Abstract

Background

Approximately 20% of patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) suffer from depression.

Objective

To compare healthcare expenditures and utilization, healthcare-related quality of life, and patient-centered outcomes among ASCVD patients, based on their risk for depression (among those without depression), and those with depression (vs. risk-stratified non-depressed).

Design and Setting

The 2004–2015 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) was used for this study.

Participants

Adults ≥ 18 years with a diagnosis of ASCVD, ascertained by ICD-9 codes and/or self-reported data. Individuals with a diagnosis of depression were identified by ICD-9 code 311. Participants were stratified by depression risk, based on the Patient Health Questionnaire-2.

Results

A total of 19,840 participants were included, translating into 18.3 million US adults, of which 8.6% (≈ 1.3 million US adults) had a high risk for depression and 18% had a clinical diagnosis of depression. Among ASCVD patients without depression, those with a high risk (compared with low risk) had increased overall and out-of-pocket expenditures (marginal differences of $2880 and $287, respectively, both p < 0.001), higher odds for resource utilization, and worse patient experience and healthcare quality of life (HQoL). Furthermore, compared with individuals who had depression, participants at high risk also reported worse HQoL and had higher odds of poor perception of their health status (OR 1.83, 95% CI [1.50, 2.23]) and poor patient-provider communication (OR 1.29 [1.18, 1.42]).

Limitation

The sample population includes self-reported diagnosis of ASCVD; therefore, the risk of underestimation of the cohort size cannot be ruled out.

Conclusion

Almost 1 in 10 individuals with ASCVD without diagnosis of depression is at high risk for it and has worse health outcomes compared with those who already have a diagnosis of depression. Early recognition and treatment of depression may increase healthcare efficiency, positive patient experience, and HQoL among this vulnerable population.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of mortality and a major contributor to healthcare expenditure in the USA.1, 2 Approximately 20% of patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) suffer from depression.3 Currently, these two conditions are the most common causes of disability in high-income countries and projected to become so for all countries by 2030.3 Evidence suggests that depression is a risk marker for cardiovascular disease and associated with worse health outcomes.3,4,5,6,7 Depression remains underdiagnosed and undertreated especially among ASCVD patients, who have a high morbidity and mortality risk even in the absence of major depression.8, 9 Despite efforts to explain the link between depression and cardiovascular outcomes, to date, the exact mechanisms that account for this relationship are unknown.10, 11 In addition to the ongoing focus on the mechanistic association between cardiovascular disease and depression, there is need to incorporate a more clinical and patient-centered approach to promote improved recognition of depression, particularly among the ASCVD population, to enhance healthcare efficiency, healthcare-related quality of life (HQoL), and health outcomes.

In a nationally representative US adult population, we compared patient healthcare experience, HQoL, resource utilization, and expenditures among non-depressed ASCVD patients, based on their risk for depression. Additionally, we compared health outcomes between ASCVD patients with and without a clinical diagnosis of depression, stratified by their risk for depression. We hypothesized that among non-depressed adults with ASCVD, those with high risk for depression would have increased healthcare expenditures and poorer healthcare quality compared with those at low risk.

METHODS

Study Design and Sampling

A retrospective analysis was performed using data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) from 2004 to 2015. MEPS, created and administered by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), is a nationally representative series of surveys of noninstitutionalized US individuals and families, their health service providers, and employers. The Household Component of MEPS (MEPS-HC) collects data about health services used, associated charges, amount paid, and sources of payment. In MEPS, detailed information about participants’ income, employment, and insurance status is available.12 Their responses are reported annually, and the AHRQ researchers assign person-weight and variance estimation stratum to each respondent based on survey non-response and the characteristics of the national population of the survey year. This allows national representativeness of the MEPS data12 (for detailed information on MEPS, see Supplementary Online Brief: eMethods).

To increase the power of the study, we included information from 2004 to 2015; two different yearly files from MEPS-HC were utilized for this study: full-year consolidated data files and medical conditions files which we merged to provide detailed information for each participant. The full-year consolidated data files include most demographic characteristics and information such as healthcare resource expenditures and utilization per person; including hospitalizations, emergency department (ED) visits, and outpatient clinic/office-based visits. The medical conditions files include participants’ self-reported and International Classification of Diseases, 9th Edition, Clinical Modification (ICD-9-CM) diagnoses of disease conditions. Since MEPS is comprised of publicly available de-identified data files, it was exempt from Institutional Review Board review.13

Study Population

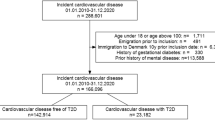

The inclusion criteria included individuals ≥ 18 years of age, with a diagnosis of ASCVD, positive sampling weights (for national representativeness), and non-missing data on patient healthcare experience variables or depression diagnosis. The initial sample consisted of 19,840 surveyed individuals (Supplementary Online Brief: eFigure 1).

Individuals in the study sample who had a diagnosis of coronary artery disease (CAD), stroke, and/or peripheral artery disease (PAD), ascertained by self-report or ICD-9-CM codes, were classified as having ASCVD. Individuals with an ICD-9-CM code of 311 were classified as having depression (Supplementary Online Brief: eMethods and eTable 1a.). The definitions for ASCVD and depression have been used in prior literature.1, 14, 15 Individuals without a diagnosis of depression were further categorized by their risk of depression (detailed below).

Depression Risk Scale

Risk for depression was assessed via the Patient Health Questionnaire-2. This scale, which ranges from 0 to 6, was initially validated by Kroenke et al. and consists of the following questions: (1) During the past two weeks, bothered by having little interest or pleasure in doing things, and (2) During the past two weeks, bothered by feeling down, depressed, or hopeless.16 The responses were provided on 4-point Likert scale: 0—not at all, 1—several days, 2—more than half the days, and 3—nearly every day. MEPS provides a summary variable from the two questions from the questionnaire; the higher the value, the greater the person’s tendency towards depression. Kroenke et al. suggest a score of 3 as the optimal cutoff point for screening purposes, with a score of ≥ 4 improving the specificity of the screener for depression16 (for further information on Depression Risk Scale, see Supplementary Online Brief: eMethods and eTable 1b). Based on this recommendation, this variable was dichotomized into the following categories: “Low Risk for Depression” (scores ≥ 0 to ≤ 3) or “High Risk for Depression” (scores ≥ 4 to ≤ 6), with the screening protocol shown in Figure 1.16 It is important to note that this tool is intended as a screening method for depression and it does not translate to a clinical diagnosis of depression.

Outcome Variables

Patient-Provider Communication and Patient Satisfaction

Each year, MEPS participants respond to questionnaires assessing patient-provider communication (PPC) derived from the Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (CAHPS) survey. After constructing a summary variable for PPC values, we classified it into the following categories: “Poor PPC,” “Average PPC,” and “Optimal PPC” (for further information on PPC, see Supplementary Online Brief: eMethods and eTable 1b.).

Patient satisfaction was assessed via the answer to the following question: “Rate of healthcare from all doctors and other health providers,” from 0 (worst healthcare possible) to 10 (best healthcare possible). To capture unsatisfied individuals, this variable was divided into quartiles (due to the skewness of individuals’ responses), with those in the lowest quartile being designated as having “Poor Patient Satisfaction.”17,18,19

Healthcare Expenditures and Resource Utilization

At the interview, participants were asked to report their annual direct medical expenditures on every health services used and/or prescription medication filled in the year. The sum of all expenditures was calculated for each person and reported as total healthcare expenditure. The sources of payment and the respective amounts contributed were also ascertained. An excess of two ED visits and two hospitalizations was used as markers for increased resource utilization as they were above the 95th utilization percentile in our study population. All expenditures were adjusted using the gross domestic product (GDP) deflator to adjust annual expenditures from 2004 to 2015 to constant 2015 US dollars (for further information on healthcare expenditure and resource utilization, see Supplementary Online Brief: eMethods).

Healthcare-Related Quality of Life and Self-perceived Health Status

Health-related quality of life was assessed using the summary scores from the physical and mental health component (PCS and MCS, respectively) from the 12-item Short Form (12-SF) version 2 included in the MEPS. The PCS and MCS scores ranged from 0 (worst health status possible) to 100 (best health status possible) and was treated as a continuous variable. The 12-SF has been previously validated for its use in the MEPS.20

Self-perceived general health was surveyed at three different points each year, with the following possible responses provided on 5-point Likert scale: 1—excellent, 2—very good, 3—good, 4—fair, and 5—poor. We averaged the responses to estimate a yearly self-perceived health estimate, which was then dichotomized into the following categories: “Poor” (average score of 5) or “Excellent/Good/Fair” (average score ≤ 4). All other covariates included in the analyses are detailed in Supplementary Online Brief: eMethods.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses accounted for the complex design of the MEPS survey, with a p < 0.05 as a marker for statistical significance. We used Stata®, version 13.1 (StataCorp, LP, College Station, TX, USA) to conduct all analyses. Chi-square tests were performed for comparison of demographic characteristics in our sample.21 Because of the right skewness of expenditure data (i.e., most expenditures are seen in only a small proportion of the population), two-part models were utilized to study expenditures.22 Two-part models are often used to model healthcare expenditures and are the product of (1) the probability that any given individual had any expenditures and (2) their mean expenditures.23, 24 We determined the distribution of the glm using the modified Park Test.25 Total and marginal expenditures were estimated using the “margins” command after the two-part models.23 Adjusted regression was used as a method of association and two-way t tests were used to compare means from our outcomes (expenditures, resource utilization, healthcare-related quality of life, and patient healthcare experience) between our study groups (ASCVD, depression, and risk of depression among those without it). The adjusted model included age, sex, race/ethnicity, socioeconomic status, cardiovascular risk factor (CRF) profile, region, marital status, and modified Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI). The specific covariates included are outlined in the Supplementary Online Brief: eMethods. Since CRF profile gives a summary of a person’s number of cardiovascular risk factors (regardless of ASCVD status), we included it in our adjusted analyses since individuals with suboptimal CRF profiles have been associated with worse outcomes overall.

RESULTS

Sample Characteristics

From 2004 to 2015, MEPS integrated 417,769 surveyed individuals, among whom 19,840 met the inclusion criteria for our study, translating to an approximate 18.3 million US adults with ASCVD. General sample characteristics are presented in Table 1. Over 1800 (representing about 1.3 million individuals nationwide) non-depressed ASCVD participants were at a high risk for depression. Approximately 18% of the study population had a diagnosis of depression, translating to 3.3 million individuals in the USA. Among patients with depression, most individuals were non-Hispanic White, middle-aged women, with an average-poor cardiovascular risk factor profile, with a combination of private and public insurance, with a low modified CCI, and living in the South (Table 1).

Non-depression: Low Risk Versus High Risk

Among ASCVD patients without depression, individuals with a high risk consistently showed worse outcomes across all categories of healthcare expense and quality (Table 2 and Supplementary Online Brief: eTable2). Those at high risk for depression presented increased overall and out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditures (marginal differences of $2880 and $287, respectively, both p < 0.001), when compared with individuals at low risk for depression. In a similar fashion, those at high risk for depression demonstrated increased odds for high healthcare utilization: ED visits (OR 2.25 [95% CI 1.62, 3.13]) and hospitalizations (OR 2.78 [95% CI 1.72, 4.45]) in multivariate analyses. Individuals at high risk also reported lower HQoL estimates, with a mean difference of − 9.75 (95% CI − 10.42, − 9.07) in PCS and − 19.69 (95% CI − 20.53, − 18.86) in MCS when compared with patients who had low risk for depression. Overall, individuals at high risk for depression had higher odds of poor perceived health status (OR 5.52 [95% CI 4.29, 7.11]), poor PPC (OR 2.41 [95% CI 1.71, 3.41]), and poor patient satisfaction (OR 3.94 [95% CI 1.45, 10.69]) (Table 2). As a sensitivity analysis, using a cutoff score of ≥ 3 to indicate high risk for depression, the direction and magnitude of the results remained the same (Supplementary Online Brief: eTable 3).

Depression Versus Non-depression—by Risk

Individuals with ASCVD and a clinical diagnosis of depression had an increased marginal healthcare expenditure and resource utilization, lower healthcare-related quality of life, poorer perception of health status, and worse patient experience when compared with those without depression, regardless of risk. These differences persisted even after adjustments for possible confounders (Supplementary Online Brief: eTable 4).

To gauge the relationship between non-depressed, high-risk individuals and those with depression, we utilized the same analyses using individuals with depression as our reference. Healthcare expenditures and resource utilization poised virtually no differences among patients with depression versus those at high risk for depression, except for ED visits which showed 13% higher odds of utilization among non-depressed ASCVD patients at high risk for depression when compared with ASCVD patients with a diagnosis of depression (OR 1.13 [95% CI 1.05, 1.21]) (Table 3). Individuals without depression and at high risk presented worse HQoL estimates with a mean difference of − 4.65 (95% CI − 5.35, − 3.95) in PCS and − 8.03 (95% CI − 9.21, − 6.86) in MCS when compared with those with depression. Additionally, those at high risk for depression had higher odds of poor perceived health status (OR 1.83 [95% CI 1.50, 2.23]) and poor PPC (OR 1.29 [95% CI 1.18, 1.42]) than those with depression (Table 3). When we compared the individual components of the PPC metrics, non-depressed ASCVD patients at a high risk for depression had higher odds of reporting poor experience in all 4 aspects of communication with their healthcare providers when compared with those with depression (Supplementary Online Brief: eTable 5). When compared against those with depression, individuals with a low risk for depression had better healthcare outcomes across the board (Table 3).

DISCUSSION

In a cohort of 19,840 participants (representing approximately 18.3 million US adults with ASCVD), we found that among individuals without a clinical diagnosis of depression, those at a high risk for it have a significantly higher rate of health resources utilization, have increased annual healthcare expenditures, were more likely to report poor healthcare experience, and have a poor perception of their health status and a lower HQoL, when compared with those at a low risk for depression. This result is further strengthened by the fact that the 12-SF is a thoroughly vetted tool for assessing HQoL in MEPS and has been used widely in past literature.1, 7, 20, 26,27,28,29,30 Furthermore, this study has distinct implications as it shows that ASCVD patients without a clinical diagnosis of depression but are at a high risk for it were more likely to report poorer health outcomes when compared with those who already have a diagnosis of depression.

Non-depressed ASCVD Patients: Low Risk Versus High Risk

The relationship between depression and adverse health outcomes appears to be graded among ASCVD patients; more severe depression is associated with an increased risk of worse health outcomes, including hospitalizations and all-cause mortality.3, 31 Although a causal relationship between depression and ASCVD is still a topic of research, depression is one of the major determinants of quality of life and thus deserves prompt recognition and early treatment to promote more favorable health outcomes.3 Studies evaluating the effect of depression screening on cardiovascular health outcomes are largely unavailable,32 although a call to action has increased in the last decade.9, 33, 34

Depression has been associated with an increase in health resource utilization and healthcare expenditure among hypertensive and diabetic patients.15, 35 We also report excess resource utilization and healthcare expenditure among ASCVD patients with a diagnosis of depression, but we further showed that even without the clinical diagnosis of depression, ASCVD patients at a high risk for it spend more on healthcare and use more health resources when compared with those at a low risk for depression. It is possible that these increased expenditures and resource utilization may be due to the self-perception of their health status as being poor, thus adversely affecting the health-seeking behavior of these individuals. Individuals with ASCVD at high risk for depression may be less likely to comply with recommended secondary prevention measures (i.e., lifestyle changes and pharmacotherapy), which drives up cost and reduces quality. Alternatively, these patients at high risk for depression may be undiagnosed depressed patients, hence the excess medical and financial burden resulting from the possible deleterious effects of depression on cardiovascular outcomes. Although a cause-effect relationship between depression risk and increased financial burden was not demonstrated, these findings are in line with those from a recent study by Annapureddy et al. which showed an association between increasing financial burden and high risk for depression.7

Poor communication between patients and their healthcare providers has been associated with adverse health outcomes among ASCVD patients.1 It has also been suggested that depression is associated with lower patient satisfaction and quality of life.36, 37 We showed that ASCVD patients at a high risk for depression were less likely to communicate effectively or be satisfied with their healthcare providers. They also had a lower HQoL when compared with ASCVD patients at low risk for depression. It would be reasonable to consider that these high-risk patients might have had concurrent depressive symptoms which may have affected their interaction with their healthcare providers or its assessment, their perception of their physical and mental health status, and ultimately their quality of life.

ASCVD Patients: Depressed Versus Non-depressed Based on Risk for Depression

Similar to our findings, overall, depression among cardiovascular patients has been associated with worse health outcomes when compared with non-depressed patients.25, 33, 38 The exact mechanism behind this association is unknown but some behavioral and biological factors are thought to play a role in the adverse health outcomes seen among depressed cardiovascular patients.39, 40 In fact, there is evidence that suggests that the risk of one condition increases with the other, in a bidirectional manner.8 Also, depression can directly influence the quality of life of an individual; therefore, the economic implication of this diagnosis especially among cardiovascular patients may be a major contributing factor to the worse health outcomes seen among these individuals. However, our study reveals that non-depressed ASCVD patients at a high risk for depression were even worse off compared with ASCVD patients with a clinical diagnosis of depression; they had a higher odds of poor patient experience, poor perception of their health status, more health resource utilization, and lower HQoL. One logical explanation for this finding is that ASCVD patients with a diagnosis of depression are most probably on treatment and are therefore more likely to have more positive patient-reported health outcomes. Conversely, non-depressed ASCVD patients at high risk for depression could be undiagnosed and untreated patients with depression in actuality, who may have less access to healthcare or are less willing to discuss their depressive symptoms with their healthcare provider, consequently associated with adverse health outcomes.

From a patient-centered approach, this calls for more aggressive depression screening among these vulnerable individuals,33, 41, 42 especially as we found no differences in health spending between high-risk non-depressed individuals and those with a clinical diagnosis of depression. The implementation of more assertive screening efforts comes in a timely fashion; a national survey of cardiovascular physicians found that half did not know that depression was an independent cardiovascular risk factor, 70% asked less than half their patients with CAD about depression, and 80% used no standard screening method.43

Limitations

Our study is not without limitations. Data from the MEPS was collected among noninstitutionalized civilian US adults, so the results obtained from this study can only be extrapolated to this population. Since MEPS has a cross-sectional design, we cannot establish causality between depression and adverse health outcomes among ASCVD patients. Furthermore, as an observational study, even after adjusting for known confounders, the risk for residual confounding from factors, such as severity of depression and type and intensity of treatment, could not be completely eliminated. Also, our sample population includes self-reported diagnosis of ASCVD and strict inclusion criteria, for which the risk of underestimation of the cohort size (or its impact on patient experience) cannot be ruled out. In addition, with the utilization of self-reported and/or ICD-9 diagnoses, there is a possibility of misclassification bias. However, using these classification parameters, the MEPS’ prevalence of ASCVD is very similar to that reported by the AHA (≈ 9% in the USA), as seen in past literature,1, 2, 44 making this type of bias very unlikely. Lastly, since there is no standardized definition for the matrices of PPC and patient satisfaction, we may not have accounted for some of the factors that influence patient experience.

Conclusion

It is estimated that 1 in 5 patients with ASCVD has depression, and our results complement current knowledge by pointing out that almost 1 in 10 individuals with ASCVD and no diagnosis of depression is at high risk for it, with worse health outcomes when compared with those who already have a diagnosis of depression. Early recognition and treatment of depression may improve health outcomes among individuals with ASCVD and are therefore worthy of further studies and discussion. We anticipate that these results could provide support for more aggressive screening strategies for depression among ASCVD patients such as reinforcing routine screening for depression during clinic visits. The results generated from this study should stimulate policy-makers and other stakeholders to explore this as a target for quality improvement interventions.

References

Okunrintemi V, Spatz ES, Di Capua P, Salami JA, Valero-Elizondo J, Warraich H, Virani SS, Blaha MJ, Blankstein R, Borden WB, Dharmarajan K, Ting H, Krumholz HM, Nasir K. Patient-provider communication and health outcomes among individuals with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the United States: Medical expenditure panel survey 2010 to 2013. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2017, 10(4).

Khera R, Valero-Elizondo J, Okunrintemi V, Saxena A, Das SR, de Lemos JA, Khrumholz HM, Nasir K. Association of out-of-pocket annual health expenditures with financial hardship in low-income adults with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the United States. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:729–738.

Hare DL, Toukhsati SR, Johansson P, Jaarsma T. Depression and cardiovascular disease: a clinical review. Eur Heart J. 2014;35(21):1365–1372.

Rudisch B, Nemeroff CB. Epidemiology of comorbid coronary artery disease and depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;54:227–240.

Thombs BD, Bass EB, Ford DE, Stewart KJ, Tsilidis KK, Patel U, Fauerbach JA, Bush DE, Ziegelstein RC. Prevalence of depression in survivors of acute myocardial infarction. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21: 30–38.

Whooley MA, de Jonge P, Vittinghoff E, Otte C, Moos R, Carney RM, Ali S, Dowray S, Na B, Feldman MD, Schiller NB, Browner WS. Depressive symptoms, health behaviors, and risk of cardiovascular events in patients with coronary heart disease. JAMA. 2008;300:2379–2388.

Annapureddy A, Valero-Elizondo J, Khera R, Grandhi GR, Spatz ES, Dreyer RP, Desai NR, Krumholz HM, Nasir K. Association between financial burden, quality of life, and mental health among those with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the United States. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11:e005180.

Lippi G, Montagnana M, Favaloro EJ, Franchini M. Mental depression and cardiovascular disease: a multifaceted, bidirectional association. Semin Thromb Hemost. 2009;35(3):325–336.

Ward HE, Tueth M, Sheps D. Depression and cardiovascular disease. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2003;16(2):221–225.

Rumsfeld JS, Ho PM. Depression and cardiovascular disease: a call for recognition. Circulation. 2005;111(3):250–253.

Mosovich SA, Boone RT, Reichenberg A, Bansilal S, Shaffer J, Dahlman K, Harvey PD, Farkouh ME. New insights into the link between cardiovascular disease and depression. Int J Clin Pract. 2008;62(3):423–432.

“Medical Expenditure Panel Survey.” Retrieved June 17th, 2019, from http://meps.ahrq.gov/mepsweb/about_meps/survey_back.jsp.

“IRB Exemption.” Retrieved June 17th, 2019, from http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/decision-trees/-c2.

Ngo-Metzger Q, Zuvekas SH, Bierman AS. Estimated impact of Us preventive services task force recommendations on use and cost of statins for cardiovascular disease prevention. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:1317–1323.

Shao H, Mohammed MU, Thomas N, Babazadeh S, Yang S, Shi Q, Shi L. Evaluating excessive burden of depression on health status and health care utilization among patients with hypertension in a nationally representative sample from the Medial Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS 2012). J Nerv Ment Dis. 2017;205:397–40.

Kroenke K., Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The Patient Health Questionnaire-2: validity of a two-item depressive screener. Med Care. 2003;41:1284–1292.

Sites BD, Harrison J, Herrick MD, Masaracchia MM, Beach ML, Davis MA. Prescription opioid use and satisfaction with care among adults with musculoskeletal conditions. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16:6–13.

Fenton JJ, Jerant AF, Franks P. Influence of elective versus emergent hospital admission on patient satisfaction. J Am Board Fam Med. 2014;27:249–57.

Jerant A. Fenton JJ, Bertakis KD, Franks P. Satisfaction with health care providers and preventive care adherence: a national study. Med Care. 2014;52:78–85.

Cheak-Zamora NC, Wyrwich KW, McBride TD. Reliability and validity of the SF-12v2 in the medical expenditure panel survey. Qual Life Res. 2009;18:727–35.

Ozieh MN, Dismuke CE, Lynch CP, et al. Medical care expenditures associated with chronic kidney disease in adults with diabetes: United States, 2011. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2015;109:185–190.

Mihaylova B, Briggs A, O’Hagan A, et al. Review of statistical methods for analysing healthcare resources and costs, Health Econ., 2011;20:897–916.

Belloti F, Deb P, Manning WG, et al., twopm: two-part models, Stata J., 2015;15:3–20.

Hardin J, HIilbe J. Generalized linear models and extensions. College Station: StataCorp LP, Stata Press; 2012.

Manning WG, Mullahy J. Estimating log models: to transform or not to transform? J Health Econ. 2001;20:461–494.

Bhandari NR, Kathe N, Hayes C, Payakachat N. Reliability and validity of SF-12v2 among adults with self-reported cancer. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2018;14:1080–1084.

Kaplan RM, Fang Z, Kirby J. Educational attainment and health outcomes: data from the Medical Expenditures Panel Survey. Health Psychol. 2017;36:598–608.

Stepanova M, De Avila L, Afendy M, Younossi I, Pham H, Cable R, Younossi ZM. Direct and indirect economic burden of chronic liver disease in the United States. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;15:759–766.

Hanmer J, Kaplan RM. Update to the report of nationally representative values for the noninstitutionalized US adult population for five health-related quality-of-life scores. Value Health. 2016;19:1059–1062.

Alenzi EO, Sambamoorthi U. Depression treatment and health-related quality of life among adults with diabetes and depression. Qual Life Res. 2016;25:1517–25.

Versteeg H, Hoogwegt MT, Hansen TB, Pedersen SS, Zwisler AD, Thygesen LC. Depression, not anxiety, is independently associated with 5-year hospitalizations and mortality in patients with ischemic heart disease. J Psychosom Res. 2013;75(6):518–25.

Thombs BD, de Jonge P, Coyne JC, Whooley MA, Frasure-Smith N, Mitchell AJ, Zuidersma M, Eze-Nliam C, Lima BB, Smith GC, Soderlund K, Ziegelstein RC. Depression screening and patient outcomes in cardiovascular care: a systematic review. JAMA. 2008;300(18):2161–2171.

Celano CM, Huffman JC. Depression and cardiac disease: a review. Cardiol Rev. 2011;19(3):130–42.

Bradley SM, Rumsfeld JS. Depression and cardiovascular disease. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2015;25(7):614–22.

Egede LE, Zheng D, Simpson K. Comorbid depression is associated with increased health care use and expenditures in individuals with diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2002;25(3):464–470.

Bui QU, Ostir GV, Kuo YF, Freeman J, Goodwin JS. Relationship of depression to patient satisfaction: findings from the barriers to breast cancer study. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2005;89(1):23–28.

de Jonge P, Spijkerman TA, van den Brink RH, Ormel J. Depression after myocardial infarction is a risk factor for declining health related quality of life and increased disability and cardiac complaints at 12 months. Heart. 2006;92(1):32–39.

Connerney I, Sloan RP, Shapiro PA, Bagiella E, Seckman C. Depression is associated with increased mortality 10 years after coronary artery bypass surgery. Psychosom Med. 2010;72(9):874–81.

Mann DL, Bristow MR. Mechanisms and models in heart failure: the biomechanical model and beyond. Circulation. 2005;111:2837–2849.

Pelle AJ, Gidron YY, Szabo BM, Denollet J. Psychological predictors of prognosis in chronic heart failure. J Card Fail. 2008;14:341–350.

Coulter SA, Campos K. Identify and treat depression for reduced cardiac risk and improved outcomes. Tex Heart Inst J. 2012;39(2):231–4.

Lichtman JH, Bigger JT Jr, Blumenthal JA, Frasure-Smith N, Kaufmann PG, Lesperance F, Mark BM, Sheps DS, Taylor BC, Froelicher ES. AHA science advisory. Depression and coronary heart disease. Recommendations for screening, referral, and treatment. A science advisory from the American heart association prevention committee to the council on cardiovascular nursing, council on clinical cardiology, council on epidemiology and prevention, and interdisciplinary council on quality of care outcomes research. Endorsed by the American psychiatric association. Prog Cardiovasc Nurs. 2009;24(1):19–26.

Feinstein RE, Blumenfield M, Orlowski B, Frishman WH, Ovanessian S. A national survey of cardiovascular physicians’ beliefs and clinical care practices when diagnosing and treating depression in patients with cardiovascular disease. Cardiol Rev. 2006;14(4):164–9.

Benjamin EJ, Virani SS, Callaway CW, Chamberlain AM, Chang AR, Cheng S, Chiuve SE, Cushman M, Delling FN, Deo R, de Ferranti SD, Ferguson JF, Fornage M, Gillespie C, Isasi CR, Jiménez MC, Jordan LC, Judd SE, Lackland D, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth L, Liu S, Longenecker CT, Lutsey PL, Mackey JS, Matchar DB, Matsushita K, Mussolino ME, Nasir K, O’Flaherty M, Palaniappan LP, Pandey A, Pandey DK, Reeves MJ, Ritchey MD, Rodriguez CJ, Roth GA, Rosamond WD, Sampson UKA, Satou GM, Shah SH, Spartano NL, Tirschwell DL, Tsao CW, Voeks JH, Willey JZ, Wilkins JT, Wu JH, Alger HM, Wong SS, Muntner P, American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention Statistics Committee and Stroke Statistics Subcommittee. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2018 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation.. 2018;137:e67-e492.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic Supplementary Material

ESM 1

(DOCX 58 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Okunrintemi, V., Valero-Elizondo, J., Michos, E.D. et al. Association of Depression Risk with Patient Experience, Healthcare Expenditure, and Health Resource Utilization Among Adults with Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease. J GEN INTERN MED 34, 2427–2434 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05325-8

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-019-05325-8