Abstract

Microbial biopolymers have recently been introduced as a new material for soil treatment and improvement. Biopolymers provide significant strengthening to soil, even in small quantities (i.e., at 1/10th or less of the required amount of conventional binders, such as cement). In particular, thermo-gelating biopolymers, including agar gum, gellan gum, and xanthan gum, are known to strengthen soils noticeably, even under water-saturated conditions. However, an explicitly detailed examination of the microscopic interactions and strengthening characteristics between gellan gum and soil particles has not yet been performed. In this study, a series of laboratory experiments were performed to evaluate the effect of soil–gellan gum interactions on the strengthening behavior of gellan gum-treated soil mixtures (from sand to clay). The experimental results showed that the strengths of sand–clay mixtures were effectively increased by gellan gum treatment over those of pure sand or clay. The strengthening behavior is attributed to the conglomeration of fine particles as well as to the interconnection of fine and coarse particles, by gellan gum. Gellan gum treatment significantly improved not only inter-particle cohesion but also the friction angle of clay-containing soils.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Several studies introducing biologically based geotechnical engineering methods for soil enhancement and treatment have recently been reported. The most common approach involves the intra-soil cultivation of microbes to produce precipitates, such as the microbially induced calcite precipitation (MICP) method [71]. The resulting precipitates then form inter-particle cementation between coarse soil particles [29, 30, 57, 85]. The MICP method has been widely explored in efforts to enhance the inter-particle cementation, which results in significant cohesion enhancement [23, 27, 53, 59] and hydraulic conductivity control [24, 28] of sandy or silty soils.

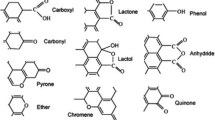

Meanwhile, different approaches using microbial excretions (e.g., biopolymers) as a binder material for various soil treatment purposes are now being actively investigated [13, 16,17,18, 45, 66]. Biopolymers are polymeric biomolecules produced by living organisms, where the monomeric units (i.e., monomers) are covalently bonded [84]. They are commonly used as thickeners or emulsifiers in food and medical products, due to their gel-phase rheological characteristics [51]. Since the introduction of biopolymers in construction engineering [68], their use for geotechnical engineering purposes has also been explored [13, 20, 35, 46, 66]. Recent studies on microbial biopolymers externally produced in culture tanks, such as polysaccharides, have demonstrated remarkable strengthening efficiency in such applications. These results suggest the potential utility of these biopolymers as a new construction material for environmentally friendly geotechnical engineering [5, 13, 14, 18, 19]. Among biopolymers suitable for soil treatment, gel-type biopolymers, such as gellan gum, agar gum, and xanthan gum, have several advantages, including quick (rapid) setting (gelation) [17], the ability to reduce hydraulic conductivity via bio-clogging [21], improving the shear resistance of soils [38, 52] and a unique gel-structure formation process that reveals high gel strength even under fully saturated conditions [22].

Soil type and soil particle composition (i.e., coarse and fine composition) are basic properties that affect soil index parameters, such as Atterberg limits [67, 80], and geotechnical engineering behaviors, such as undrained shear strength [73, 82], soil stiffness and compressibility [12, 15] and hydraulic conductivity [56]. In terms of soil improvement, the presence of clays in soils inhibits the cementation of cement- or lime-mixed soils, due to the expansion of a double layer of clay particles that reduce adhesion between clay particles and cement hydrates [79]. Moreover, high clay content is known to reduce the calcite precipitation efficiency due to the low void ratio and permeability of fine soils that restrict microbe or nutrient solutions transport in soil, thus limiting the application of MICP for real, in situ practices [62, 63].

Among other types of biopolymers, the gel-type biopolymers show better inter-particle interactions with clay particles than with coarse particles, such as sand [16, 17]. The interactions between gel-type biopolymers and clay particles result in greater strengthening due to direct ionic or hydrogen bonding and matrix formation, while neutral sand particles undergo no direct bonding with biopolymers. For sand, gellan gum biopolymer provides strengthening to gellan gum–sand mixtures due to the condensation and aggregation effects of the high tensile gellan gum hydrogels among the sand particles [21]. However, a detailed understanding of the interactions between gellan gum and soils and their strengthening behavior, especially for sand–clay mixtures with different clay contents, has yet to be achieved. Thus, the present study was conducted to investigate the inter-particle interactions and strengthening behavior of gellan gum-treated soils, ranging from sand to clays, through a series of experimental laboratory tests.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Gellan gum-treated soil mixtures

2.1.1 Gellan gum biopolymer

Gellan gum is a high molecular weight polysaccharide group biopolymer produced by the bacterium Sphingomonas elodea. The most notable characteristic of gellan gum is its thermo-gelation property: Its solubility and viscosity are temperature dependent. Gellan gum exhibits poor solubility at low temperature, while sufficient gum dissolution with random coil conformation forms uniform gellan gum solutions at temperatures higher than 90 °C [39]. Upon temperature decrease, randomly dispersed gellan gum coils adopt a double-helical structure through ionotropic sol–gel transition, which results in high viscous and firm gellan gum gel formation [26, 61]. Details of the gellan gum rheology and a case study of experimental implementations can be found in Chang et al. [17, 22]. Low acyl gellan gum (CAS No: 71010-52-1) was used in this study to verify the interaction between soils and gellan gum, without the presence of additional cations, which alter the gelation and strength of gellan gum gels.

2.1.2 Sand–clay mixtures

Jumunjin sand, a standard sand in Korea, was used for the experimental tests in this study. Jumunjin sand is classified as poorly graded sand (SP) according to the USCS classification, with soil properties of D50 = 0.52 mm, Cu = 1.35, Cc = 1.14, Gs = 2.65, emin = 0.644, and emax = 0.892.

For clay, Bintang kaolin (Belitung Island, Indonesia), a commercially available white kaolin clay material, was used. Bintang kaolin is classified as CH according to the USCS classification, having soil properties of PL = 24, LL = 62, Gs = 2.65, and D50 = 44 μm.

Clean sand and clay were dried in an oven before specimen preparation. Different sand–clay mixtures were obtained by mixing dry sand and clay at the mass ratios (i.e., mc/ms; clay-to-soil ratio in mass, where mc/ms = 1.0 indicates pure clay) listed in Table 1. The liquid limits of the prepared sand–clay mixtures (except pure sand) were evaluated via a fall cone test using a 30°, 80 g British cone [7, 9]. The liquid limit of the sand–clay mixtures was LL = 17 at mc/ms = 0.2 and was gradually increased to 40 and 62 for mc/ms = 0.5 and 1.0 soils, respectively (Table 1).

Initial water content (w) values for gellan gum–soil mixtures were determined by considering both clay (mc/ms) and gellan gum content (mb/ms) to the total weight of soil (i.e., higher w values with higher clay and gellan gum contents). For example, the initial water content of the gellan gum–soil mixtures should be higher than the LL of untreated (natural) soils to provide thorough mixing due to the hydrophilic water holding and retention capacity of biopolymers [10], which increases the LL of biopolymer–soil mixtures [14]. Thus, the w values have been fixed as 60, 50, 40, and 30% for mc/ms = 1.0, 0.5, 0.2, and 0 soils, respectively (Table 2).

2.1.3 Preparation of gellan gum-treated soils

To prepare thermo-gelated gellan gum-treated soil mixtures, dry gellan gum was first dissolved and hydrated in pure water heated to 120 °C, to obtain a mb/mw = 5% gellan gum solution (mb/mw = gellan gum content to the mass of water). Thereafter, a dry sand–clay mixture and the hot mb/mw = 5% gellan gum solution were uniformly mixed at mw/ms (gellan gum solution to the mass of soil ratio) = 20%, resulting in thermo-gelated mb/ms = 1% gellan gum-treated soil with initial w = 20%. Additional heated distilled water was added and mixed thoroughly to achieve the desired initial water content, as listed in Table 2 (e.g., w = 30, 40, 50, and 60% for mc/ms = 0.5 soil).

For laboratory vane shear tests, the gellan gum-treated soil mixtures (mb/ms = 1%) were poured into a rectangular cup made of acryl having inner dimensions of 50 mm width, 50 mm length, and 50 mm depth. The thermo-gelated specimens were tightly sealed with laboratory vacuum packing to prevent surface evaporation. Temperature change was measured via a radiation thermometer to verify complete cooling (at room temperature) of the thermo-gelated gellan gum-treated soils.

For direct shear tests, the thermo-gelated gellan gum-treated soil mixtures were molded into disk shapes 60 mm in diameter and 20 mm in height. The specimens were submerged in water and cooled to maintain the initial conditions of each gellan gum-treated soil specimen.

2.2 Laboratory vane shear tests

In general, vane shear tests are used to determine soil surface shear strengths for near-zero effective confinements [8], where vane shear tests are widely performed to measure the undrained shear strength of soils in the laboratory and in situ [11].

In the present study, primary laboratory vane shear tests (I) were performed using a 12.7-mm rectangular vane (vane thickness t = 0.5 mm; perimeter ratio α = 5%) [6] on both untreated and gellan gum-treated (with and without thermo-gelation, respectively) soil specimens, which had different soil compositions and initial water contents. Although the laboratory vane shear test presents problems with organic soils due to uncertain failure conditions around the vane circumference [50], three specimens were tested and averaged to represent a single soil condition with minimum uncertainty. The vane was pushed 30 mm into the soil from the top surface to place the blade directly in the middle of the specimens and then rotated constantly with a 10°/min angular velocity [36].

Secondary laboratory vane shear tests (II) were conducted to evaluate the effect of the gellan gum–clay interaction (i.e., mb/mc; gellan gum-to-clay ratio in mass) on the vane shear strength behavior of the thermo-gelated gellan gum-treated soils, where mc/ms = 0.5 and 1.0 soils at a water content of w = 40% were considered. The ratio mb/ms was maintained at 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5% for pure clays (mc/ms = 1.0), while it was reduced to half those amounts for mc/ms = 0.5 soils, respectively, to obtain identical mb/mc conditions of 1–5% for both soil compositions. The aforementioned experimental procedures of soil mixing, molding, cooling, and strength measurement used for the primary laboratory vane shear tests were also adopted.

Because a 12.7 × 12.7 mm vane was applied, the obtained laboratory vane shear strength (τv) values were τv = M/4.29 (kPa), where M (N mm) is the measured torque at failure. Rod friction [76] and shear rate [3] effects were neglected due to the small penetration depth of 30 mm and the low peripheral velocity of 1.1 mm/min.

2.3 Direct shear test

The direct shear test is appropriate for evaluating qualitative stress–strain behaviors along a thin zone of shear failure, especially for granular materials where drainage is not a consideration [37, 49]. Moreover, a relatively small-scale circular-type direct shear apparatus of 60 mm in diameter has substantial advantages, such as the ability to provide consistent and reliable evaluation of strength parameters, including ϕd and cd, as demonstrated by numerous measurements [65].

Soils with mc/ms = 1.0, 0.5, 0.2, or 0 (i.e., pure sand) were mixed with thermo-gelated gellan gum, as summarized in Table 2. Gellan gum-treated soils were prepared with gellan gum-to-clay ratios (mb/mc) of 1, 2, 3, 4, or 5% at different initial water contents (e.g., 60% for pure clay, 30% for pure sand).

Gellan gum-treated soil specimens were placed in a circular shear box having a 60-mm inner diameter and 25 mm height (HM-2701.60D). Porous stones were placed above and beneath the sample. The shear box was filled with water to saturate the gellan gum-treated soil and prevent any moisture loss from the specimen during testing. The initial dry densities before loading were 0.96, 1.23, 1.62, and 1.42 g/cm3 on average for mc/ms = 1.0, 0.5, 0.2, and 0 soils, respectively. The target overburden stress of σv = 50, 100, 200, and 400 kPa was applied via a pneumatic actuator for 24 h to ensure that there was no further vertical displacement before the horizontal shear displacement test.

A direct shear testing device (Humboldt HM-2560A) was used to perform direct shear tests. Horizontal shear displacement was applied at a rate of 0.01 mm/min for 10-mm total horizontal displacement [2]. For biopolymer-treated soils, the elapsed time of horizontal shearing must be at least 49250 s due to the high water holding capacity and low coefficient of consolidation (Cv) values of biopolymer-treated clays (i.e., Cv = 0.2 × 10−7 m2/s, at void ratio = 0.9 for beta-glucan-treated clay) [14, 58]. However, although horizontal shearing has been applied slowly, it is hard to present a perfect drained condition during a direct shear test on gel-type biopolymer-treated soils due to the high water holding capacity of gellan gum hydrogels [17, 21]. Thus, the direct shear test results from this study have been interpreted in terms of direct shear strength, direct shear dilation angle, direct shear cohesion and direct shear friction angle where notations become τf, ψd, cd, and ϕd, respectively.

Shear load and vertical and shear displacements were measured automatically via a load cell (HM-2300.020) and an LVDT (HM-14368, HM-14180). Specimen preparation and direct shear testing were performed at the same room temperature (20 °C) to avoid viscosity variation effects of gellan gum gels with temperature change. At least three specimens were tested to obtain a representative value for each condition depending on mc/ms, mb/mc, and σv.

2.4 Scanning electron microscope (SEM) images

SEM images were taken to observe the microscale interactions between gellan gum and soil particles for 1% gellan gum-treated soils (mc/ms = 1.0 and 0.5). The undisturbed condition was investigated by sampling a 0.5-cm3 piece of a cube (10 mm wide, 10 mm long, 5 mm high) of dried gellan gum-treated soil that had not been subjected to any testing. The disturbed condition was investigated by collecting fragments of 1% gellan gum-treated soil that had been crushed during unconfined compression tests. Both undisturbed and disturbed sample pieces were attached to a 25-mm-diameter SEM mount by carbon conductive tabs (PELCO Tabs™). Carbon paint (DAG-T-502) was applied to the sample edges and bottoms to provide sufficient grounding. Specimens were coated via an osmium plasma coater (OPC-60A) using osmium tetroxide (OsO4) as the source of osmium, for 20 s under vacuum. An extreme high-resolution SEM (FEI Magellan 400L XHR) was used to observe the microscopic structure and particle alignment of the gellan gum-treated soil samples.

3 Results and analysis

3.1 Laboratory vane shear strength (τ v)

3.1.1 1% gellan gum-treated soils for various initial water contents

The results for dry density and laboratory vane shear strength of the mb/ms = 1% gellan gum-treated soils at various water contents are shown in Fig. 1. The dry densities of both untreated and gellan gum-treated soils showed a single trend with water content regardless of the gellan gum treatment (Fig. 1a). The vane shear strength (τv) increased with a reduction in the initial water content and an increase in the clay content (Fig. 1b). Gellan gum treatment increased the shear strength significantly for all soil mixtures, even with high water content.

In general, gellan gum forms uniform hydrocolloids and transforms into firm hydrogels via thermo-gelation upon cooling, and the resulting hydrogels have extremely high water holding capacity (i.e., absorbability) [61]. As a result, the overall shear strengths of the gellan gum-treated soils remain much higher than those of untreated soils, even above the LL values (Table 1) of the untreated condition, and also decrease gradually with increasing water content. Moreover, soils with lower mc/ms show higher strengthening efficiency (i.e., the τv of 1% gellan gum-treated soil/τv of untreated soil), which implies that the gellan gum-to-clay ratio in mass (mb/mc) is a possible dominant parameter influencing the strengthening behavior of gellan gum-treated soils.

3.1.2 Different percent gellan gum-treated soils with the same initial water content

The secondary laboratory vane shear test results for different percent gellan gum-treated soils (mc/ms = 0.5 and 1.0) at a similar dry density = 1.15 g/cm3 (w = 40%) are shown in Fig. 2. The vane shear strength (τv) values of both soils increase with higher gellan gum content (mb/ms) and converge after certain mb/ms conditions are met (Fig. 2a). From the viewpoint of clay content, both soils show an upper limit of shear strength at mb/mc = 4% (Fig. 2b), which implies that the strengthening behavior is dominated by the gellan gum–kaolinite clay matrix formed via thermo-gelation.

Hydrated biopolymers are known to be effective coagulants for clay particles [74, 75], while electrically neutral sand particles (e.g., those with ionic- or hydrogen bonding) have no direct interaction with biopolymers [5, 16]. For this reason, the interaction between gellan gum and clay particles can be facilitated by lowering the mc/ms values, which results in higher mb/mc. The vane shear strength of soils thus can be effectively improved by gellan gum treatment, changing the soil composition and optimizing the gellan gum-to-clay ratio.

3.2 Shear stress and vertical strain behaviors with shear displacement

Typical direct shear test results of gellan gum-treated soils are shown in Fig. 3. The vertical strain (εv) values were calculated from the changes in the height of the sample relative to the initial height of the sample (20 mm). Negative values indicate volumetric contraction. The maximum direct shear dilation angle (ψd) values were estimated from the steepest slope (Δvertical displacement/Δhorizontal displacement) of shear displacement—vertical strain curves [42, 54], as shown in Fig. 3b, d, f.

Figure 3a, b presents the shear behavior of untreated (mb/ms = 0%) natural soils at an overburden stress of σv = 50 kPa. Differences between the peak shear strength and the residual shear strength increased with lower clay content, whereas the volumetric change behavior became more dilative with the same clay content. In detail, untreated soils start to show peak τf and ψf values for sand contents of 80% and 100%. When the weight of the sand in the sand–clay mixtures is higher than 75%, the shear behavior of the sand–clay mixtures is governed mainly by the frictional resistance between sand grains [83]. Thus, soils containing 80% sand appear to follow the shear behavior of sand grains (with peaks), while soils of mc/ms = 0.5 and 1.0 show strain-hardening behaviors.

Figure 3c, d shows the shear behavior of gellan gum-treated soils (clay = 20% and mb/ms = 1%) under different overburden stress conditions. Gellan gum treatment instantly increased the τf and ψd of the soils (e.g., comparison of 50-kPa overburden stress results). As the overburden stress increased, τf of the gellan gum-treated soils increased (Fig. 3c), while the soils become less dilative (Fig. 3d).

Figure 3e, f reveals the shear behavior of different percent gellan gum-treated soils (mc/ms = 0.5 and an overburden stress of 50 kPa). As the mb/ms ratio was increased (i.e., higher gellan gum content), the τf and ψd increased, and thus, the soil showed more brittle and dilative behavior. It was found that the gellan gum treatment induced a structural agglomeration effect (i.e., forming gellan gum–clay matrices), which is similar to cementation. This finding is consistent with the general τf and ψd increments observed with cemented [4, 43] and polymer-treated [40] soils.

3.3 Shear strength and overburden stress relationships

The direct shear strengths of thermo-gelated gellan gum-treated soils are shown in Fig. 4. Overall, the direct shear strength increases linearly with the increase in overburden stress, regardless of the soil composition and gellan gum treatment. The soil composition affects the strength of untreated (i.e., natural) soils: the ϕd of untreated soils decreases with increasing mc/ms, i.e., ϕd = 9.3° for pure sand → ϕd = 8.7° for pure clay. Meanwhile, gellan gum treatment increases the strength of the soils significantly, with ϕd and cd increases with increasing mb/ms or mb/mc.

As shown in Fig. 4a, the ϕd of pure sand is negligibly affected by gellan gum treatment, whereas the cd is substantially increased with increasing gellan gum content. Cement treatment on sand is known to accompany increases of cd, while there are opposing views on the ϕd behavior of cement–sand mixtures. Some studies indicate an increase in ϕd with cementation [25, 47, 77], contrasting with results showing a constant ϕd regardless of cement-treated sands with a high degree of compaction (Dr) [32, 44, 72]. However, the ϕd of gellan gum-treated sand remains constant, regardless of the gellan gum content and Dr of the specimens in this study. Cement-treated sand consists of a solid phase (sand grains and C-S-H hydrates) only after cement hydration, while gellan gum-treated sand contains solid grains and hydrogels in voids. The presence of gellan gum hydrogels in sand pores only affects cd depending on the gel concentration, without any effect on the mechanical behavior (ψd, ϕd) of sand [21]. Thus, the shear behavior of gellan gum-treated sand should be interpreted differently than that of cement-treated sands.

Meanwhile, clay-containing soils show a remarkable increase in ϕd as well as cd with a sequential increase in mb/mc (Fig. 4b, c, d), which is consistent with the general behavior of cement-treated clays [55, 70, 78]. The presence of a small amount of gellan gum (mb/mc = 1%) in clay-containing soils immediately induced a remarkable increase in ϕd, whereas ϕd gradually increases with higher mb/mc (> 1%) conditions which implies that the gellan gum treatment not only contributes to the increase in cd but also contributes to the conglomeration of fine particles (i.e., clay) to form partially conglomerated aggregates, resulting in an increase in dilatancy and ϕd, respectively.

Meanwhile, the cd of gellan gum-treated soils increased consistently with increasing mb/mc or mb/ms ratios. Gellan gum treatment plays an important role in cd enhancement, regardless of soil type. The cd value of gellan gum-treated soils is highly correlated with the gellan gum–clay matrix (mb/mc), which shows a similar increment in cd to the subsequent increase in mb/mc.

In general, an increase in ϕd induces higher shear strength and bearing capacity at greater depths, while the increase in cd becomes meaningful for subsurface soil strengthening. Thus, it can be concluded that gellan gum treatment can be effective for improving the shear strength of shallow subsurface sand layers, such as seashore or arid region dunes, by increasing cd (Fig. 4a). It also may be effective in improving the shear strength of deep clayey soil deposits via ϕd as well as cd increment (Fig. 4d), which results in a remarkable increase in the bearing capacity of soils. Moreover, the significant increase in shear strength for gellan gum-treated sandy soils (Fig. 4a) implies the potential value of applying gellan gum in geotechnical aseismic practices, such as increasing resistance to liquefaction. Specifically, this shear strength increase results from improved residual shear strength and shear stiffness, as shown in Fig. 3a, c, e, which enhances the post-liquefaction parameters of sands at shallow depths [1, 31, 86].

4 Discussion

4.1 Shear strength parameters of gellan gum-treated soils

Figure 5 presents the direct shear strength (τf) of gellan gum-treated soils with various mb/ms ratios at different overburden stress (σv) levels. The direct shear strength of soils with less clay content increases more rapidly with an increase in the mb/ms ratio. That is, the direct shear strength of soils with large amounts of clay or pure sand increases gradually with an increasing mb/ms ratio. All the gellan gum-treated soil mixtures were prepared with mb/mc ranging from 0 to 5%, and the highest τf value was exhibited at lower mb/ms conditions, for soils with lower clay content.

Regarding the gellan gum to clay (mb/mc = (mb/ms)/(mc/ms)) composition, gellan gum-treated soils reached a maximum τf at mb/mc ≥ 4% regardless of the mc/ms and σv (Fig. 5a, b), consistent with the laboratory vane shear strength (τv) behavior shown in Fig. 2b. The τf values of gellan gum-treated soils at high σv (200 and 400 kPa) gradually increased with lower clay content under the same mb/ms conditions, as shown in Fig. 5c, d which implies the importance of the physical interlocking between granular grains on the shear strength behavior when the inter-granular gellan gum–clay matrices are identical (i.e., with the same mb/mc). Meanwhile, as expected, the τf of pure sand was generally lower than that of clay-containing soils, due to the lack of a gellan gum-clay matrix.

Figure 6 shows the shear strength parameters (cd and ϕd) of gellan gum-treated soils with varying mb/mc contents. As shown in Fig. 6a, the cd values of gellan gum-treated soils increase sequentially with increasing mb/mc and reach their maximum value at around mb/mc = 4%. The decrease in cd at mb/mc > 4% appears to be affected by surplus gellan monomers, which can cause ionic repulsion or hydrologic swelling, resulting in a reduction of gellan gum–clay interaction. Nevertheless, it can be cautiously predicted that clay materials with larger specific surfaces (e.g., montmorillonite) should show maximum strengths at mb/mc values higher than 4%.

Meanwhile, as shown in Fig. 6b, the ϕd values of the gellan gum-treated sand (clay 0%) have less dependency on changes in mb/ms, while the ϕd values of the gellan gum-treated clayey soils increase abruptly with the presence of a small amount of gellan gum (i.e., mb/mc = 1%) and subsequently converge or slightly increase with increasing mb/mc. Therefore, the addition of even a small amount of gellan gum can effectively improve the ϕd of clayey soils. The larger ϕd improvement effect observed with mc/ms = 0.2 and 0.5 soils indicates that not only the inter-granular friction of sand grains, but also the conglomerated gellan gum–clay matrix inside the inter-granular pores, or between sand particles, significantly governs the overall friction behavior (including significant ψd increase; Fig. 3f) of gellan gum-treated soils.

With regard to soil composition, gellan gum treatment of single-grained soils (pure sand and pure clay) appears to be more appropriate for increasing cd (Fig. 6a), while gellan gum treatment of multi-grained soils (mc/ms = 0.2 and 0.5) shows significant increases in ϕd (Fig. 6b). However, it should be noted that the cd and ϕd values shown in Fig. 6 are presented with variations in mb/mc instead of mb/ms. This means that the absolute quantity of gellan gum becomes less at lower mc/ms ratios in the order 1.0 → 0.5 → 0.2. For instance, mb/mc = 5, 2, and 1% exhibit mb/ms = 1% conditions identical to mc/ms = 0.2, 0.5, and 1.0 soils, respectively.

The cd and ϕd of gellan gum-treated soils are presented with mb/ms variations in Fig. 7. cd (Fig. 7a) shows a strong correlation with mb/ms, regardless of soil composition, while the ϕd (Fig. 7b) becomes relatively higher for multi-grained soils, regardless of mb/ms conditions. The ϕd of pure sand remains almost constant with mb/ms variation, while the ϕd of pure clay becomes almost identical to the ϕd of pure sand at high mb/ms conditions. ϕd values of sand–clay mixtures become higher than those of single-grained soils, which can be ascribed to the effect of the conglomeration between gellan gum–clay matrices and sand particles. Thus, it can be concluded that the cd characteristic of gellan gum-treated soils is strongly affected by the ratio of the absolute quantity of gellan gum to the amount of soil (mb/ms), rather than to the soil composition and mb/mc matrices; meanwhile, the ϕd characteristic of gellan gum-treated soils is governed by the multi-grain composition and mb/mc variation rather than the mb/ms ratio.

4.2 Microscopic interaction and shear model of gellan gum-treated soils

Figure 8 shows SEM images of 1% gellan gum-treated mc/ms = 1.0 and 0.5 soils. Clay particles and gellan gum monomers form a firm and well-bonded gellan gum–clay matrix via hydrogen bonding [17, 48, 64], as shown in Fig. 8a–d. Gellan gum and gellan gum–clay matrices show no direct interaction (e.g., hydrogen or ionic bonds) with sand particles for both undisturbed (Fig. 8e) and disturbed conditions (Fig. 8f). Thus, it appears that the gellan gum–clay matrix dominates the strengthening behaviors of gellan gum-treated soils.

For pure clay, gellan gum chains, with average lengths of 100 nm, can form connections between kaolinite particle edges, inducing an accumulation of stacks of kaolinite particles (Fig. 8a). Because gellan gum is an anionic biopolymer [61], gellan gum monomers are expected to attach to positively charged kaolinite particle edges and enhance plate particle stacking. Inter-particle bonds can be broken or detached when gellan gum-treated soils are subjected to macro-strain disturbances, such as crushing by unconfined compression tests (Fig. 8b). Therefore, the strengthening behavior of gellan gum-treated soils can be explained as a combination of the following: (1) the formation of a gellan gum gel or gellan gum–clay matrix, which immediately enhances cd; (2) a conglomeration effect induced by gellan gum–clay matrices, which instantly increases dilatancy and ϕd; and (3) higher strength with higher water content due to the LL increase [14] induced by hydrophilic biopolymer treatment.

Figure 9 shows schematic models of the microstructural evolution of gellan gum-treated soils during direct shear tests. For pure sand (Fig. 9a), gellan gum gels are condensed among sand grains and thus do not affect the ϕd (fabric change) but do provide a significant contribution to cd during shear, as already shown in Fig. 4(a). However, the ϕd will increase when the gellan gum gels are fully dried, by forming a surface coating and enlarging inter-particle contact areas [21].

For pure clay (Fig. 9b), gellan gum gels bond with themselves and clay particles. They thereby facilitate bonding among clay particles and conglomeration of clay particles during shear, increasing both the ϕd and cd. The ϕd of gellan gum-treated pure clay increases due to the restricted slippage, which is governed by the high tensile gellan gum chains connecting clay particles. Gellan gum also provides a significant improvement in cd (Fig. 6a). Although natural clay generally contracts with shearing, gellan gum-treated pure clay shows dilative behavior during direct shearing due to the conglomeration induced by the formation of gellan gum–clay matrices (Fig. 3b).

For sand–clay mixtures (Fig. 9c), gellan gum gels enhance interactions between clay particles and between sand grains, producing an instant increase in cd. Moreover, the conglomeration of the gellan gum–clay and gellan gum–clay–sand matrices induces a considerably higher ϕd, causing accumulated gellan gum–clay matrices to behave as secondary grains between sand particles. Thus, the ϕd of gellan gum-treated sand–clay mixtures becomes remarkably higher than that of single grain soils (pure sand or pure clay) (Fig. 6b) and dominates the shear behavior of sand–clay mixtures.

4.3 Potential of gellan gum treatment in geotechnical engineering practices

The results of this study show that mb/mc becomes the dominant parameter governing the strengthening behavior of gellan gum-treated soils. Field engineers thus can determine the optimum quantity of gellan gum needed to provide the most effective strengthening based on the soil type (USCS classification) and clay content in the soil (mc/ms).

For low plasticity clay (CL), 5% cement treatment improves the c from 75.5 to 152.1 kPa, while the ϕ increases from 27.5° to 34.2° after 28 days of curing [81]. However, for gellan gum treatment, 4% gellan gum-treated pure clay enhances the cd from 18.5 kPa to 127.3 kPa and the ϕd from 18.7° to 30.7° only 12 h after treatment (Fig. 6). Thus, gellan gum treatment shows potential to be applied for quick and immediate soil stabilization or improvement purposes in geotechnical engineering practices. Moreover, gellan gum can become a promising binder for the currently increasing demands on eco-friendly raw earth buildings and constructions [33, 60].

Meanwhile, despite the positive impact on the shear behavior of gellan gum biopolymer-treated soils, practical realization becomes an important concern for gellan gum biopolymer usage in real in situ practices. High-temperature control and thorough mixing or injection into soils with high fine contents become challenges for the future commercialization of gellan gum biopolymer in the field of geotechnical engineering. Thus, further research is required to develop detailed construction methods and systems, as well as relevant machinery, which have high compatibility with existing construction technologies.

Moreover, economic concerns regarding gellan gum utilization for soil treatment remain, based on its relatively high cost compared to conventional soil treatment materials such as ordinary cement. Chang et al. [21] showed that the total cost to treat one ton of soil with gellan gum via thermal treatment is approximately US$25-30, comparable to the current cost (US$10) of 10% cement treatment. However, recent analyses of economic feasibility and prospects show that the use of biopolymers for construction purposes is becoming more feasible as a result of the current rapid growth of the global biopolymer market [34, 41, 69].

5 Conclusions

Through a series of experimental programs, this study explored the strengthening behavior of gellan gum-treated soils (from sand to clay). The results of laboratory vane shear strength (τv) and direct shear strength parameters (cd, ϕd, τf) for different sand–clay mixtures treated by gellan gum indicate that gellan gum treatment enhances the strength of soils significantly and that the strengthening behavior of gellan gum-treated soils involves a combination of phenomena. These include (1) the formation of a gellan gum gel or gellan gum–clay matrix, which enhances cd; (2) conglomeration induced by gellan gum–clay matrices, which increases the ϕd; and (3) higher internal strength of gellan gum-treated soils due to the water holding characteristic of hydrophilic gellan gum. Indeed, further strengthening due to gellan gum gels or gellan gum–clay matrix condensation with drying is also expected.

For soils with clay, the strengthening has a unique characteristic that invariably depends on the gellan gum-to-clay ratio in mass (mb/mc). In detail, the gellan gum–clay matrix of kaolinite clay is optimized at around mb/mc = 4% for gellan gum–kaolinite mixtures, regardless of the soil composition (i.e., mc/ms) and soil water content. However, mb/mc conditions higher than 4% are expected to yield convergence or even a reduction in strength due to ionic repulsion or hydrophilic swelling of surplus gellan gum monomers, which remain unbonded with clay particles.

The microstructure of gellan gum-treated soils indicates the formation of direct hydrogen bonding between gellan gum monomers and clay particles, especially at positively charged edges. The resulting gellan gum–clay matrices increase the shear strength of soils by enhancing cd and conglomeration, resulting in an increase in the ϕd of soils. When the goal is the strengthening of soils, sand–clay mixtures have advantages that result in higher strength due to the conglomeration effect between the gellan gum–clay matrix and granular particles.

The findings obtained from this study provide a guideline for optimal gellan gum treatment in geotechnical engineering practices. The results of this study show that mb/mc becomes the dominant parameter governing the strengthening behavior of the gellan gum-treated soils. Thus, field engineers can determine the optimum quantity of gellan gum needed to provide the most effective strengthening based on the soil type (USCS classification) and clay content in the soil (mc/ms). If the clay mineral is mainly kaolinite, mb/mc = 4% can be recommended for maximum strength capacity, while other clay types should be evaluated in further studies.

The significant shear strength and stiffness enhancement of gellan gum-treated sandy soils for low overburden stress suggest the significant potential of gellan gum applications for geotechnical earthquake-related soil management practices where an increase in both cyclic shear resistance and post-liquefaction shear strength is desired. Considering the aspect of environmental friendliness, gellan gum treatment can be applied for various geotechnical engineering purposes such as soil stabilization, deep mixing, surface erosion reduction, temporary soil structures, and so on. Moreover, the rapidly growing global biopolymer market and carbon emission trading market are improving the economic feasibility of gellan gum–soil technologies as a promising in situ implementation approach in the near future.

Abbreviations

- w :

-

The soil water content (%) to the mass of soil

- m b :

-

The mass of biopolymer (gellan gum, in this study)

- m s :

-

The mass of soil

- m c :

-

The mass of clay

- m c/m s :

-

The clay content in soil

- LL:

-

The liquid limit of soils

- q u :

-

The unconfined compressive strength of soils

- τ v :

-

Vane shear strength obtained by laboratory vane shear test (kPa)

- m b/m s :

-

Gellan gum-to-soil ratio in mass

- m b/m c :

-

Gellan gum-to-clay ratio in mass

- τ :

-

Shear stress in direct shear specimens during horizontal shearing

- δ :

-

Horizontal displacement during direct shear test (mm)

- ε v :

-

Vertical stain during direct shear test

- ψ d :

-

Angle of dilation during direct shear test

- σ v :

-

Overburden stress for direct shear test

- τ f :

-

Direct shear strength obtained by direct shear testing

- c d :

-

Soil cohesion obtained by direct shear test (kPa)

- ϕ d :

-

Soil friction angle obtained by direct shear test (°)

References

Andrus RD, Stokoe KH II (2000) Liquefaction resistance of soils from shear-wave velocity. J Geotech Geoenviron Eng 126(11):1015–1025. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0241(2000)126:11(1015)

ASTM D3080/D3080 M-11 (2011) Standard test method for direct shear test of soils under consolidated drained conditions. ASTM International, West Conshohocken. https://doi.org/10.1520/D3080_D3080M-11

Biscontin G, Pestana JM (2001) Influence of peripheral velocity on vane shear strength of an artificial clay. Geotech Test J 24(4):423–429. https://doi.org/10.1520/GTJ11140J

Bolton MD (1986) The strength and dilatancy of sands. Géotechnique 36(1):65–78. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.1986.36.1.65

Bouazza A, Gates WP, Ranjith PG (2009) Hydraulic conductivity of biopolymer-treated silty sand. Géotechnique 59(1):71–72. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.2007.00137

British Standard Institute (1990) BS 1377-7: Methods of test for soils for civil engineering purposes. Part 7–Shear strength tests (total stress). British Standard Institute, London

British Standard Institute (2014) BS EN ISO 17892-1: Geotechnical investigation and testing. Laboratory testing of soil. Part 1–Determination of water content. British Standard Institute, London

Brunori F, Penzo MC, Torri D (1989) Soil shear strength: its measurement and soil detachability. CATENA 16(1):59–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/0341-8162(89)90004-0

Budhu M (1985) The effect of clay content on liquid limit from a fall cone and the British Cup Device. Geotech Test J 8(2):91–95. https://doi.org/10.1520/GTJ10515J

Cao J, Jung J, Song X, Bate B (2018) On the soil water characteristic curves of poorly graded granular materials in aqueous polymer solutions. Acta Geotech 13(1):103–116. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-017-0568-7

Chandler RJ (1988) The in-situ measurement of the undrained shear strength of clays using the field vane. In: Vane shear strength testing in soils: field and laboratory studies vol 1014, p 13

Chang I, Cho G-C (2010) A new alternative for estimation of geotechnical engineering parameters in reclaimed clays by using shear wave velocity. Geotech Test J 33(3):171–182. https://doi.org/10.1520/GTJ102360

Chang I, Cho G-C (2012) Strengthening of Korean residual soil with β-1,3/1,6-glucan biopolymer. Constr Build Mater 30:30–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2011.11.030

Chang I, Cho G-C (2014) Geotechnical behavior of a beta-1,3/1,6-glucan biopolymer-treated residual soil. Geomech Eng 7(6):633–647. https://doi.org/10.12989/gae.2014.7.6.633

Chang I, Kwon T-H, Cho G-C (2011) An experimental procedure for evaluating the consolidation state of marine clay deposits using shear wave velocity. Smart Struct Syst 7(4):289–302. https://doi.org/10.12989/sss.2011.7.4.289

Chang I, Im J, Prasidhi AK, Cho G-C (2015) Effects of Xanthan gum biopolymer on soil strengthening. Constr Build Mater 74:65–72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.10.026

Chang I, Prasidhi AK, Im J, Cho G-C (2015) Soil strengthening using thermo-gelation biopolymers. Constr Build Mater 77:430–438. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.12.116

Chang I, Prasidhi AK, Im J, Shin H-D, Cho G-C (2015) Soil treatment using microbial biopolymers for anti-desertification purposes. Geoderma 253–254:39–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoderma.2015.04.006

Chang I, Jeon M, Cho G-C (2015) Application of microbial biopolymers as an alternative construction binder for earth buildings in underdeveloped countries. Int J Polym Sci 2015:9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/326745

Chang I, Im J, Cho G-C (2016) Introduction of microbial biopolymers in soil treatment for future environmentally-friendly and sustainable geotechnical engineering. Sustainability 8(3):251. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8030251

Chang I, Im J, Cho G-C (2016) Geotechnical engineering behaviors of gellan gum biopolymer treated sand. Can Geotech J 53(10):1658–1670. https://doi.org/10.1139/cgj-2015-0475

Chang I, Im J, Lee S-W, Cho G-C (2017) Strength durability of gellan gum biopolymer-treated Korean sand with cyclic wetting and drying. Constr Build Mater 143:210–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.02.061

Cheng L, Cord-Ruwisch R, Shahin MA (2013) Cementation of sand soil by microbially induced calcite precipitation at various degrees of saturation. Can Geotech J 50(1):81–90. https://doi.org/10.1139/cgj-2012-0023

Chu J, Ivanov V, Stabnikov V, Li B (2013) Microbial method for construction of an aquaculture pond in sand. Géotechnique 63(10):871–875. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.SIP13.P.007

Consoli NC, Prietto PDM, Ulbrich LA (1998) Influence of fiber and cement addition on behavior of sandy soil. J Geotech Geoenviron Eng 124(12):1211–1214. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0241(1998)124:12(1211)

Coutinho DF, Sant S, Shin H, Oliveira JT, Gomes ME, Neves NM, Khademhosseini A, Reis RL (2010) Modified gellan gum hydrogels with tunable physical and mechanical properties. Biomaterials 31(29):7494–7502. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.06.035

Cui M-J, Zheng J-J, Zhang R-J, Lai H-J, Zhang J (2017) Influence of cementation level on the strength behaviour of bio-cemented sand. Acta Geotech 12(5):971–986. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-017-0574-9

Dadda A, Geindreau C, Emeriault F, du Roscoat SR, Garandet A, Sapin L, Filet AE (2017) Characterization of microstructural and physical properties changes in biocemented sand using 3D X-ray microtomography. Acta Geotech 12(5):955–970. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-017-0578-5

De Muynck W, De Belie N, Verstraete W (2010) Microbial carbonate precipitation in construction materials: a review. Ecol Eng 36(2):118–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecoleng.2009.02.006

DeJong J, Fritzges M, Nüsslein K (2006) Microbially induced cementation to control sand response to undrained shear. J Geotech Geoenviron Eng 132(11):1381–1392. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0241(2006)132:11(1381)

Do J, Heo S-B, Yoon Y-W, Chang I (2017) Evaluating the liquefaction potential of gravel soils with static experiments and steady state approaches. KSCE J Civ Eng 21(3):642–651. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12205-016-1365-9

Dupas J-M, Pecker A (1979) Static and dynamic properties of sand-cement. J Geotech Eng Div 105(3):419–436

Gallipoli D, Bruno AW, Perlot C, Mendes J (2017) A geotechnical perspective of raw earth building. Acta Geotech 12(3):463–478. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-016-0521-1

GBI Research (2010) Global biopolymer market forecasts and growth trends to 2015—starch-based polymers driving the growth. Global Business Institute, New York

Ham S, Kwon T, Chang I, Chung M (2016) Ultrasonic P-wave reflection monitoring of soil erosion for erosion function apparatus. Geotech Test J 39(2):301–314. https://doi.org/10.1520/GTJ20150040

Head KH (1994) Manual of soil laboratory testing, vol 2, 2nd edn. Pentech Press, London

Holtz RD, Kovacs WD, Sheahan TC (2011) An introduction to geotechnical engineering, 2nd edn. Pearson, Upper Saddle River

Im J, Tran ATP, Chang I, Cho G-C (2017) Dynamic properties of gel-type biopolymer-treated sands evaluated by Resonant Column (RC) tests. Geomech Eng 12(5):815–830. https://doi.org/10.12989/gae.2017.12.5.815

Imeson A (2010) Food stabilisers, thickeners and gelling agents. Wiley-Blackwell Publishing, Chichester

Isik I, Yilmazer U, Bayram G (2003) Impact modified epoxy/montmorillonite nanocomposites: synthesis and characterization. Polymer 44(20):6371–6377. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0032-3861(03)00634-7

JEC Group (2008) Biopolymers: market potential and challenging research, vol 39. JEC Composites Magazine, Paris

Jewell RA (1989) Direct shear tests on sand. Géotechnique 39(2):309–322. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.1989.39.2.309

Jewell RA, Wroth CP (1987) Direct shear tests on reinforced sand. Géotechnique 37(1):53–68

Juran I, Riccobono O (1991) Reinforcing soft soils with artificially cemented compacted-sand columns. J Geotech Eng 117(7):1042–1060. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9410(1991)117:7(1042)

Khatami H, O’Kelly B (2012) Improving mechanical properties of sand using biopolymers. J Geotech Geoenviron Eng 139(8):1402–1406. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0000861

Kwon Y-M, Im J, Chang I, Cho G-C (2017) ε-polylysine biopolymer for coagulation of clay suspensions. Geomech Eng 12(5):753–770. https://doi.org/10.12989/gae.2017.12.5.753

Lade PV, Overton DD (1989) Cementation effects in frictional materials. J Geotech Eng 115(10):1373–1387. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9410(1989)115:10(1373)

Laird DA (1997) Bonding between polyacrylamide and clay mineral surfaces. Soil Sci 162(11):826–832. https://doi.org/10.1097/00010694-199711000-00006

Lambe TW, Whitman RV (1969) Soil mechanics. Series in soil engineering. Wiley, New York

Landva AO (1980) Vane testing in peat. Can Geotech J 17(1):1–19. https://doi.org/10.1139/t80-001

Lapasin R (1995) Rheology of industrial polysaccharides: theory and applications. Springer, Berlin

Lee S, Chang I, Chung M-K, Kim Y, Kee J (2017) Geotechnical shear behavior of xanthan gum biopolymer treated sand from direct shear testing. Geomech Eng 12(5):831–847. https://doi.org/10.12989/gae.2017.12.5.831

Lin H, Suleiman MT, Brown DG, Kavazanjian E (2016) Mechanical behavior of sands treated by microbially induced carbonate precipitation. J Geotech Geoenviron Eng 142(2):04015066. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0001383

Lings ML, Dietz MS (2004) An improved direct shear apparatus for sand. Géotechnique 54(4):245–256. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.2004.54.4.245

Lorenzo G, Bergado D (2004) Fundamental parameters of cement-admixed clay—new approach. J Geotech Geoenviron Eng 130(10):1042–1050. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0241(2004)130:10(1042)

Marion D, Nur A, Yin H, Han DH (1992) Compressional velocity and porosity in sand-clay mixtures. Geophysics 57(4):554–563. https://doi.org/10.1190/1.1443269

Martinez B, DeJong J, Ginn T, Montoya B, Barkouki T, Hunt C, Tanyu B, Major D (2013) Experimental optimization of microbial-induced carbonate precipitation for soil improvement. J Geotech Geoenviron Eng 139(4):587–598. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0000787

Miyoshi E, Takaya T, Nishinari K (1996) Rheological and thermal studies of gel-sol transition in gellan gum aqueous solutions. Carbohydr Polym 30(2–3):109–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0144-8617(96)00093-8

Montoya BM, DeJong JT (2015) Stress-strain behavior of sands cemented by microbially induced calcite precipitation. J Geotech Geoenviron Eng 141(6):04015019. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0001302

Morales L, Romero E, Jommi C, Garzón E, Giménez A (2015) Feasibility of a soft biological improvement of natural soils used in compacted linear earth construction. Acta Geotech 10(1):157–171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-014-0344-x

Morris ER, Nishinari K, Rinaudo M (2012) Gelation of gellan—a review. Food Hydrocolloids 28(2):373–411. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.foodhyd.2012.01.004

Mortensen BM, Haber MJ, DeJong JT, Caslake LF, Nelson DC (2011) Effects of environmental factors on microbial induced calcium carbonate precipitation. J Appl Microbiol 111(2):338–349. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2672.2011.05065.x

Mujah D, Shahin MA, Cheng L (2017) State-of-the-art review of biocementation by microbially induced calcite precipitation (MICP) for soil stabilization. Geomicrobiol J 34(6):524–537. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490451.2016.1225866

Nugent R, Zhang G, Gambrell R (2009) Effect of exopolymers on the liquid limit of clays and its engineering implications. Transp Res Rec J Transp Res Board 2101:34–43. https://doi.org/10.3141/2101-05

O’Rourke T, Druschel S, Netravali A (1990) Shear strength characteristics of sand-polymer interfaces. J Geotech Eng 116(3):451–469. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0733-9410(1990)116:3(451)

Orts W, Roa-Espinosa A, Sojka R, Glenn G, Imam S, Erlacher K, Pedersen J (2007) Use of synthetic polymers and biopolymers for soil stabilization in agricultural, construction, and military applications. J Mater Civ Eng 19(1):58–66. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)0899-1561(2007)19:1(58)

Palomino AM, Burns SE, Santamarina JC (2008) Mixtures of fine-grained minerals—Kaolinite and carbonate grains. Clays Clay Miner 56(6):599–611. https://doi.org/10.1346/ccmn.2008.0560601

Plank J (2005) Applications of biopolymers in construction engineering. In: Biopolymers Online. Wiley-VCH Verlag GmbH & Co. KGaA, Weinheim. https://doi.org/10.1002/3527600035.bpola002

Platt DK (2006) Biodegradable polymers: market report. Smithers Rapra Limited, Shrewsbury

Prabakar J, Dendorkar N, Morchhale RK (2004) Influence of fly ash on strength behavior of typical soils. Constr Build Mater 18(4):263–267. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2003.11.003

Qabany AA, Soga K (2013) Effect of chemical treatment used in MICP on engineering properties of cemented soils. Géotechnique 63(4):331–339. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.SIP13.P.022

Rad N, Tumay M (1986) Effect of cementation on the cone penetration resistance of sand: a model study. Geotech Test J 9(3):117–125. https://doi.org/10.1520/GTJ10617J

Reddi LN, Bonala MVS (1997) Critical shear stress and its relationship with cohesion for sand.kaolinite mixtures. Can Geotech J 34(1):26–33. https://doi.org/10.1139/t96-086

Renault F, Sancey B, Badot PM, Crini G (2009) Chitosan for coagulation/flocculation processes—an eco-friendly approach. Eur Polym J 45(5):1337–1348. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2008.12.027

Ruhsing Pan J, Huang C, Chen S, Chung Y-C (1999) Evaluation of a modified chitosan biopolymer for coagulation of colloidal particles. Colloids Surf A 147(3):359–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0927-7757(98)00588-3

Schlue B, Mörz T, Kreiter S (2007) Effect of rod friction on vane shear tests in very soft organic harbour mud. Acta Geotech 2(4):281–289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-007-0047-7

Schnaid F, Prietto P, Consoli N (2001) Characterization of cemented sand in triaxial compression. J Geotech Geoenviron Eng 127(10):857–868. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0241(2001)127:10(857)

Sezer A, İnan G, Yılmaz HR, Ramyar K (2006) Utilization of a very high lime fly ash for improvement of Izmir clay. Build Environ 41(2):150–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.buildenv.2004.12.009

Shawabkeh RA (2005) Solidification and stabilization of cadmium ions in sand–cement–clay mixture. J Hazard Mater 125(1–3):237–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhazmat.2005.05.037

Sridharan A, Rao SM, Murthy NS (1988) Liquid limit of kaolinitic soils. Géotechnique 38(2):191–198. https://doi.org/10.1680/geot.1988.38.2.191

Tang C, Shi B, Gao W, Chen F, Cai Y (2007) Strength and mechanical behavior of short polypropylene fiber reinforced and cement stabilized clayey soil. Geotext Geomembr 25(3):194–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geotexmem.2006.11.002

Thevanayagam S (1998) Effect of fines and confining stress on undrained shear strength of silty sands. J Geotech Geoenviron Eng 124(6):479–491. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0241(1998)124:6(479)

Vallejo LE, Mawby R (2000) Porosity influence on the shear strength of granular material-clay mixtures. Eng Geol 58(2):125–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0013-7952(00)00051-X

Van de Velde K, Kiekens P (2002) Biopolymers: overview of several properties and consequences on their applications. Polym Testing 21(4):433–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0142-9418(01)00107-6

van Paassen L, Ghose R, van der Linden T, van der Star W, van Loosdrecht M (2010) Quantifying biomediated ground improvement by ureolysis: large-scale biogrout experiment. J Geotech Geoenviron Eng 136(12):1721–1728. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)GT.1943-5606.0000382

Youd TL, Idriss IM, Andrus RD, Arango I, Castro G, Christian JT, Dobry R, Finn WDL, Harder LF Jr, Hynes ME, Ishihara K, Koester JP, Liao SSC, Marcuson WF, Martin GR, Mitchell JK, Moriwaki Y, Power MS, Robertson PK, Seed RB, Stokoe KH II (2001) Liquefaction resistance of soils: summary report from the 1996 NCEER and 1998 NCEER/NSF workshops on evaluation of liquefaction resistance of soils. J Geotech Geoenviron Eng 127(10):817–833. https://doi.org/10.1061/(ASCE)1090-0241(2001)127:10(817)

Acknowledgements

The research described in this paper was financially supported by a National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) grant funded by the Korean government (MSIP) (No. 2017R1A2B4008635). A Grant (18AWMP-B114119-03) from the Water Management Research Program and a Grant (18SCIP-B105148-04) from the Construction Technology Research Program both funded by the Ministry of Land, Infrastructure and Transport (MOLIT) of the Korean government also supported this research.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Chang, I., Cho, GC. Shear strength behavior and parameters of microbial gellan gum-treated soils: from sand to clay. Acta Geotech. 14, 361–375 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-018-0641-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11440-018-0641-x