Abstract

The growing prominence of patient and public involvement in health services has led to the increased use of experiential knowledge alongside medical and professional knowledge bases. Third sector organisations, which position themselves as representatives of collective patient groups, have established channels to communicate experiential knowledge to health services. However, organisations may interpret and communicate experiential knowledge in different ways, and due to a lack of inherent authority, it can be dismissed by health professionals. Thus, drawing on individual interviews with organisation representatives, we explore the definitions and uses of as well as the ‘filters’ placed upon experiential knowledge. The analysis suggests that whilst experiential knowledge is seen as all-encompassing, practical and transformative, the organisations need to engage in actions that can tame experiential knowledge and try to balance between ensuring that the critical and authentic elements of experiential knowledge were not lost whilst retaining a position as collaborators in health care development processes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Patient organisations and advocacy groups, made up of and representing people with lived experiences, have become important influencers in matters related to health and illness, health care and policy (Brown et al. 2004; Jongsma et al. 2018). As representatives of the ‘voice’ of patients, they bring knowledge derived from lived experiences into decision making and aggregate individual interests into collective interest through participation, deliberation and representation (Jongsma et al. 2018). Landzelius (2006) has suggested that these groups can be placed along a spectrum, ranging from informal (e.g. loose networks, online communities) to formal (e.g. organisations with governing structures, strategical targets and official planners). Although the groups and activists at the informal end of the spectrum can influence attitudes and mobilise action, the more formal organisations are the ones that are often granted access to decision making in relation to health services and policy. Indeed, in several countries third sector organisations are included in the planning and development of health services (Van de Bovenkamp et al. 2010; Martin 2012; Pavolini and Spina 2015). As patient and public involvement has become an integral aspect of many health developed health systems (Fredriksson and Tritter 2017), the role of these organisations in health service planning and development may be further solidified. These developments have also led to experiential knowledge being viewed as a distinctive form of knowledge and a contribution that patients make to decision making in the health field (Blume 2017). Experiential knowledge is founded upon people’s individual and collective experiences of illness and service use (Beresford 2019). However, prior studies have highlighted the heterogeneous nature of experiential knowledge, and how it is often underused and undervalued in health care (Noorani et al. 2019). Therefore, it is important to ask how the organisations claiming to represent experiential perspectives understand the concept of experiential knowledge and its’ uses in health services. Thus far, experiential knowledge has mainly been explored from the perspective of patients and carers (e.g. Caron-Flinterman et al. 2005; Boardman 2014; Castro et al. 2019). By focusing on third sector organisations, we widen the perspective and deepen the conceptual understanding of experiential knowledge. We begin by introducing the concept of experiential knowledge and highlight the various ways in which it can be interpreted. Following this, we will discuss the role of third sector organisations as representatives of patients and their experiences in involvement activities.

Experiential Knowledge

Lived experiences can be described as the embodied, social and emotional experiences of living with an illness. Additionally, they can include experiences of treatment and services use. These experiences can offer insights into the everyday management of illness and recovery (Rowland et al. 2017). Lived experiences and experiential knowledge are closely interlinked, as the illness experiences are the basis upon which experiential knowledge is formed. This suggestion was made already in the 1970s by Borkman (1976), who argued that “experiential knowledge is truth learned from personal experience with a phenomenon rather than truth acquired by discursive reasoning, observation, or reflection on information provided by others”. Over the following decades, academics, people with lived experiences and groups representing them have adopted this concept and developed it further. Borkman (1990) herself continued to redefine the concept, describing experiential knowledge as holistic rather than piecemeal (like folk/lay knowledge) or specialised (like professional knowledge), emerging from the continuous and layered experiences of living with a problem. However, since Borkman’s initial analysis, the concept of experiential knowledge has become less clear-cut (Boardman 2014). It has been suggested that experiential knowledge can support coping, as it helps with practical aspects of involved with living with a problem, including dealing with service providers, financial costs and how to deal with poor but well-meaning advice (Vennik et al. 2014; Noorani et al. 2019). Additionally, experiential knowledge can includes experiences of stigma, interpersonal relationships, emotions and key existential-spiritual questions (Noorani et al. 2019). Moreover, it has also been described as embodied and situated knowledge about vulnerability (Rowland et al. 2017), a way to challenge underlying assumptions about illness and to create a more nuanced understanding of the lived illness experiences (Faulkner 2017). Thus, experiential knowledge can comprise of several types of experiences and information, including embodied and social aspects. Another aspect that can be added to the mix is that of ‘systemic knowledge’ described by Willis et al. (2016) who argue that people acquires knowledge regarding the health care system and how to navigate it.

Although anyone with an illness can be regarded as having personal lived experiences, some authors have argued that experiential knowledge goes beyond the personal and is created through sharing and distiling personal experiences together. Rabeharisoa and Callon (2004) have argued that single experiences do not necessarily make valid experiential knowledge, as its production requires a process in which the experiences of a broad and diverse group are collected, aggregated and formalised. Caron-Flinterman et al. (2005) have suggested that people can generate experiential knowledge by processing their lived experiences, which can lead to new insights and ways of coping. For decades, third sector organisations have provided a basis for this knowledge to form and develop through peer support groups and other activities that bring patients together. These activities facilitate the creation of a shared pool of knowledge that is produced by combining peoples’ lived illness experiences (Caron-Flinterman et al. 2005). However, Blume (2017) has suggested that there are numerous constraints that ‘filter’ the experiences, which come to function as experiential knowledge. This means that although experiential knowledge could be viewed as a wider pool of understanding, certain experiences may be excluded or deemed less valued. The emphasis placed on sharing and pooling experiences together to produce experiential knowledge suggests that although it is deeply rooted in embodied and social experiences, it not merely tacit. Experiential knowledge can be explicated and applied to provide new insights for the benefit of health services.

Despite the growing prominence of experiential knowledge in health services and in academic literature on lived experiences, it has also been argued that due to its subjective nature, the application of experiential knowledge to expert fields such as medicine should be limited. Indeed, Prior (2003) has argued that although people may have knowledge of their personal circumstances and may be able to challenge medical professionals on issues, their knowledge base is limited, they are unable to distinguish which issues require attention and may be plain wrong about the course and management of illnesses. Indeed, for some people the sources of information regarding illnesses may be rather limited. These ideas may be at least partially shared by health services as studies have highlighted that knowledge derived from lived experiences can often be dismissed, disregarded or included as a token gesture (Daykin et al. 2007; Boivin et al. 2010; Greenhalgh et al. 2015; Noorani et al. 2019). Thus, it can be challenging for organisations to use experiential knowledge in environments where it is not viewed as valuable or legitimate. Mazanderani et al. (2012) have suggested that there needs to be more exploration into how experiences are turned into different forms of knowledge and used in health care. Studies regarding experiential knowledge have largely focused on the perspectives of the individuals with lived illness experiences (e.g. Caron-Flinterman et al. 2005; Boardman 2014; Noorani et al. 2019). Our aim is to explore how organisations claiming to represent the ‘voice’ of lived experience define experiential knowledge and what are their experiences of using experiential knowledge in health services.

The Role of Third Sector Organisations

Despite the current role of many organisations as representatives and advocacy groups, lived experiences have not always been valued as a source of knowledge by the third sector. Indeed, the organisations and associations founded during the 19th and early 20th century were the realm of philanthropists and society women, far removed from the experience of illness (Barbot 2006). Self-help groups and increasingly specialised organisations founded that sprang up from the 1960s and 1970s onwards, were more susceptible to personal experiences. However, it was still largely the doctors and researchers that were considered to possess expert knowledge (Barbot 2006). Over the later part of the 20th century, groups organised around health-related issues have been able to influence both policy and service delivery by altering conceptions and broadening the rights of patients (Brown et al. 2004).

In this study, we will focus especially on patient and illness specific organisations, which have increased in numbers particularly throughout the Nordic countries (Winblad and Ringård 2009). The core duties of these organisations include the provision of peer support and self-help, informing members of new policies and providing medical/research information concerning specific illnesses (Ternhag et al. 2005). On a more general societal level, the organisations can seek to raise awareness and influence cultural norms and attitudes in order to reduce stigma (Baggott and Jones 2018). The close interaction with the membership and the provision of different activities enable the organisations to gather the experiences and views of people with lived experiences. Setälä and Väliverronen (2014) have coined the term field expert, to describe a group of people who have become mediators of scientific expertise. In many ways, this term also applies to representatives of third sector organisations whose role is twofold. They act as ‘translators’ or ‘knowledge brokers’ (Meyer 2010), translating medical information regarding specific illnesses and treatment to the organisation’s membership. However, towards health professionals and decision makers as their role is to provide ‘experiential representation’ (Martin 2008) and communicate experiential knowledge forward. Hence, organisations inhabit a somewhat hybrid space, where they often incorporate both clinical and experiential perspectives (Näslund 2020). In order to fulfil this role, the organisations need to ‘stay in close contact with the patient population they represent, verifying the mutuality of demands, ideas and judgements regularly’ (Caron-Flinterman et al. 2005: 2582). Although organisations are nowadays much more inclined to value lived experiences as a source of knowledge and even expertise, they may have very different understandings of the content of lived experiences, and they adopt different styles of communicating experiences within health service planning and development. Indeed, Rowland et al. (2017) have highlighted that concepts such as the patient perspective, and patient experiences can be interpreted in different ways, which in turn can create dilemmas in the implementation of involvement activities.

In this study, we explore how collective groups representing people with lived experiences describe the content and uses of experiential knowledge. Third sector organisations have, at least in theory, become channels through which patients can influence health-related decision making (Torjesen et al. 2017). They act as partners and collaborators in the planning, management and delivery of services and often have a seat at the table at the level of policy development (Martin 2012) in Finland and elsewhere. Therefore, it is important to examine experiential knowledge also from their perspective. Mankell and Fredriksson (2020) have described the roles of organisations in terms of support, service-provision and representation. In this study, we will focus specifically on the support and representation aspects as experiential knowledge can be constructed and gathered through the supportive activities and disseminated through the representative role. It should also be added that during the 2000s and the 2010s, many organisations have begun to train people as experts by experience (i.e. people with lived experiences who can participate in service and policy level development work) in addition to training peer support workers or provide training that prepares patients/people with lived experiences to participate in research processes.

We will focus on organisations dedicated to two large and varied patient groups (cancer and mental health problems) which have established relationships with political decision makers and have engaged in involvement activities. Gathering examples from cancer and mental health organisations provides interesting insights into these issues as there is a great variety of organisations representing people form these illness groups. Additionally, cancer and mental health organisations have established positions as active participants in service development and they currently provide training for people with lived experiences. Some have even formed networks for their respective ‘diseases’ within parliament (Toiviainen et al. 2010) and are regularly consulted during policy making processes and included in the planning, organisation and delivery of health services (Ministry of Social Affairs and Health 2011; Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare 2014; Ministry of Social Affairs and Health 2019).

Although the organisations can vary in composition and size, they all use and promote lived experiences and act as representatives of the ‘voice’ of patients. In this study, we will firstly ask: (1) How do representatives of third sector organisations describe the content and scope of experiential knowledge and what arguments do they provide for its use in health services? As prior studies have suggested, the promotion and use of experiential knowledge within health service planning and development can be challenging, posing prerequisites on experiential knowledge (Blume 2017; Jones 2018). Therefore, we will also explore: (2) What kinds of ‘filters’ are imposed on experiential knowledge as it is communicated to health professionals by organisations?

Materials and Methods

In order to gather a range of perspectives, we conducted individual interviews with representatives from small- and large-scale, national and regional level organisations e.g. with membership ranging between 100 to 20,000, and the number of paid employees ranging from zero or one to dozens. We chose organisations, which represent two common and wide illness groups, cancer and mental health. The involvement of people from these illness groups and the involvement of organisations representing their interests have been actively promoted in Finnish health policies and health service strategies (Ministry of Social Affairs and Health 2011; Jones & Pietilä 2018). Therefore, the representatives from cancer and mental health organisations have experiences of involvement in health sector and have been required provide ‘experiential representation’ (Martin 2008) and communicate experiential knowledge to health services. Despite representing different patient/illness groups and varying in size and structure, there were also many similarities. Providing information and support were among their core functions, together with advocacy and raising awareness. As mentioned before, the organisations communicate information to varied groups as they transfer and translate scientific/medical knowledge to their membership and offer experiential knowledge to health services and policy makers. The organisations participating in this study used a variety of methods to gather lived experiences. They created spaces where experiences were shared, such as online platforms and peer groups, conducted surveys and posted questions in online chat forums. The organisations also trained people with lived experiences to become peer support workers and experts by experience, which in turn supported the creation of experiential knowledge. The knowledge gathered from members was used to inform the organisations’ agenda. Experiential knowledge provided legitimacy to the organisations’ claims that they were representing patients and their lived perspectives.

The interviews analysed in this study were conducted with representatives (n = 11) of seven different organisations. Four of these were cancer organisations, and three organisations represented people with mental health problems. All the interviewees were either the managers of these organisations or employees whose work was directly related to the organisations’ involvement activities. Four of the participants also possessed lived illness experiences. The interviews were conducted during 2017 and 2018 by the first author. Prior to the interviews, ethical approval was obtained from the Academic Ethics Committee of the Tampere Region and all the participants gave verbal and written informed consent. A thematic interview guide was used in all the interviews in order to cover similar issues with all the participants (e.g. organisations aim and functions, services and training provided, collaboration with health services). However, the guide was used loosely for the participants to freely discuss the themes and issues they regarded relevant. The interviews were recorded and transcribed verbatim. All names and references to places have been removed from the extracts used in the results section in order to ensure anonymity (Table 1).

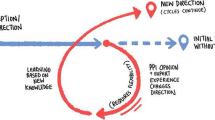

This study draws on methods of discourse analysis and focuses on how language is being used, and the functions that language has (Potter and Wetherell 1987). During the first stage of analysis, notes were written in the transcripts, and preliminary coding was done to identify parts of the interviews, where participants discussed the gathering and uses of experiential knowledge. Once we had identified these extracts in the transcripts, we focused specifically on them. The aim was to find recurrent patterns of talk—i.e.similarities and differences in the participants’ descriptions of experiential knowledge and how they talked about the organisation’s role in providing experiential representation in health service development. During this process, we noticed that the participants talked about different limitations and prerequisites that were placed on experiential knowledge as they were communicating it to health professionals. Hence, we decided to look at both the similar patterns in their descriptions of experiential knowledge and the expectations posed on experiential knowledge. From the abstracts, we analysed how the participants described the content and uses of experiential knowledge, and the different stages of gathering, processing and communicating experiential knowledge. Using Blume’s (2017) term, we titled the restrictions and expectations placed on experiential knowledge at these different stages as ‘filters’. The term ‘taming’ was chosen to highlight the overall challenges faced by organisations as they attempted to represent lived experiences. By imposing different ‘filters’, experiential knowledge was to a degree being ‘tamed’ as it was processed and structured. Concurrently, the participants also wanted to ensure that the transformative power of lived experiences was not lost and as organisations they wanted to maintain their autonomy despite working closely with health services. At the final stage of the analysis, the findings were grouped under two sections, first of which focuses on the ways in which the participants described and understood the content of experiential knowledge. The second section explores the filtering and taming of experiential knowledge.

Results

We have divided the results into two sections. The first section introduces the three ways in which the interview participants described experiential knowledge—all-encompassing, practical and transformative. The all-encompassing descriptions related to the nature of experiential knowledge. It was argued that in relation to other forms knowledge (e.g. clinical) experiential knowledge could offer a multilayered understanding of health, illness and care. Thus, it could be used to expand the perceptions of health professionals. The other two descriptions were more connected to the functions of experiential knowledge. The suggestion was that individuals’ lived experiences can be translated into practical information about concrete issues and practices that could be enhanced the treatment and care experiences. However, the main aim was not to use experiential knowledge only for practical purposes, but to transform the way in which health services function, and how decisions are being made. Despite these aims, experiential knowledge continues to lack inherent authority in health services, which can lead to a need to tame it.

Experiential Knowledge: Providing All-Encompassing, Practical and Transformative Perspectives

First and foremost, the participants highlighted that experiential knowledge is strongly founded upon lived experiences. The organisations ran several groups and networks through which these experiences could be shared, gathered and processed. Therefore, in order to become experiential knowledge, experiences needed to be verbalised and structured. There were some ambivalences in the participants descriptions on whether experiential knowledge could be based on individual experiences alone or whether it was a combined pool of knowledge, consisting of several peoples’ experiences. Despite some of the conflicting descriptions, experiential knowledge was mainly discussed as a combination of different experiences and perspectives. It provided an insight into the everyday life of living with and managing an illness and took into consideration the embodied, social and emotional aspects of these experiences. A common feature of the interviews was that the participants repeatedly contrasted experiential knowledge with medical and professional knowledge. In these comparisons, the participants claimed that by its very nature experiential knowledge was all-encompassing, offering a more rounded and nuanced understanding of illness and treatment. These comparisons also contained criticism towards the clinical and highly specialised ways medical and professional knowledge view illness and treatment:

You know exactly how a surgeon is going to treat you. They may not have any interest in the person at all, since they are just interested in the specific part that’s being operated.

In contrast to this distant, narrow and clinical approach, where the individual and their experience are forgotten, experiential knowledge was described as providing a grounding in’reality’. The participants emphasised the need to view people as wholes, considering their life experiences and situations. As opposed to knowledge that could be learned, experiential knowledge was also described as authentic. It could be used to convey deeply personal emotions and embodied sensations. This all-encompassing knowledge could convey people’s vulnerability and fragility during periods of distress. It was described as particularly powerfully when it was relayed by someone with personal experiences, as it allowed the listeners to connect to the illness experience on a personal and emotional level. As all-encompassing, experiential knowledge could also serve to expand professionals’ perceptions of illness and care:

When health professionals are trained, doctors are trained, specialist doctors, then well… there should be a shift from science to the realities of life, as it would enhance understanding. I remember as a nursing student how it was always great when someone came to give a talk and explained that they had an illness and came to talk about what it’s like. There were only a few of [these talks] back then, but sometimes they happened. And they provided a sense of realism, how the diagnosis or the illness or these issue have an impact, when there’s a real person talking about it.

Although, experiential knowledge was compared to medical and professional knowledge, it was not positioned as a replacement. On the contrary, the participants argued that different forms of knowledge should be combined and used together, in order to gain a fuller understanding of lived perspectives and services use. Therefore, experiential knowledge was described as a piece that was currently missing from health service development. Involvement practices enabled the organisations to work in closer collaboration with health professionals, managers and decision makers, creating new practices and approaches. When discussing the contributions that experiential knowledge could offer to health services and existing practices, the participants argued that experiential knowledge could translate into practical suggestions to enhance care and the service user experience. These practical uses of experiential knowledge could provide help with issues such as improving hospital parking instructions, guidance about accessing information, patient facilities within hospitals or functioning of care pathways:

At least on issues related to cancer it can benefit patients, since they are experts by experience on how the care pathway is functioning. So, this kind of expertise of customer experience, it can provide feedback on cancer cervices as a product. What went well and what could be improved. So it’s good for that at least… What else could it be used for? Well, at least that was a clear area, customer feedback, from an expert by experience.

In the above extract, the interviewee refers to people with lived experiences as experts who can and ought to be consulted on practical issues related to treatment and care. They also use rather market-oriented terminology in relation to involvement and experiential knowledge. The person with lived experiences is positioned as a customer, whose knowledge and information need to be gathered to enhance the ‘product’ (i.e. cancer care). This type of terminology was not as strongly present in the other interviews, nevertheless, other participants also provided examples of experiential knowledge containing practical information about service performance, which is only possessed by people who have used that specific service. Although the participants felt that experiential knowledge could be translated into these highly practical improvement suggestions, they also argued that it was not enough to use experiential knowledge merely for these purposes. Indeed, they voiced concerns that if experiential knowledge was only viewed from this narrow perspective, much of its’ content and potential would be lost. Hence, the participants expressed that it should also “have an impact on the [health service] structures and not just be cosmetic, like picking the right colours for chairs or tablecloths”.

This idea was further supported in the descriptions that highlighted experiential knowledge as transformative. It offered unique and at times critical information that could benefit health services and health professionals. Experiential knowledge was created outside of health services, and it can offer a new perspective on issues. The aim was to challenge the ‘old culture’ within health care and integrate experiential knowledge into all decision making processes. In the next extract, the interviewee places experiential knowledge on an equal footing with research knowledge and argues that despite their differences, these forms of explaining and understanding health and illness should be used in conjunction:

In my opinion, involvement is extremely important. That you start to discover, without dismissing the old culture that is good and continues to exist, but you start adding to it. […] And if we want to really change something, like structures, then the thinking needs to change first. […] At the end of the day, it’s a beautiful and a logical, unalterable point that research knowledge and experiential knowledge need to start interacting. And that can be made to happen by thinking about structures and doing concrete collaboration and trying to understand. And that can produce something that is more […] but there’s still a lot to do in relation to structures and in relation to getting organised.

In the above extract, the participant acknowledges that structural changes would need to occur for experiential knowledge to be viewed in equal terms. However, he suggests that the acceptance and use of experiential knowledge could lead to brand new innovations. The extract also highlights some of the problems that participants faced as they tried to integrate experiential knowledge into health services. Feeling that experiential knowledge was not valued caused frustration amongst the organisations as they were unable to get important points across. Overall, the different descriptions provided by the interviewees contained an underlying suggestion that the knowledge possessed by health professionals and decision makers was important but somewhat insufficient. Adding experiential perspectives could improve the services both in practical terms but also create more profound changes in professionals’ perceptions of illness and treatment, as well as care and decision making practices. Moreover, the descriptions portray experiential knowledge as critical and authentic, bringing into light the embodied, social and emotional aspects of being ill. However, communicating this knowledge to health services was not as straight forward, and the interviewees expressed that certain adjustments needed to be made. In the next section, we will explore the restrictions placed on experiential knowledge and explore how the participants attempted to manage these restrictions.

The Taming of Experiential Knowledge

The participants identified several actions and choices that could be viewed as attempts to tame experiential knowledge. Therefore, by taming we refer to the varied adjustments made and the ‘filters’ posed on the ways in which experiential knowledge was communicated. Some of these appeared to be self-imposed, as the organisations were trying to establish themselves as valued collaborators and wanted to entice health professionals to become more receptive to experiential knowledge. We will initially address the issue of representation and discuss who is considered eligible to communicate experiential views. Following this, we will move on to discuss the issue of language and explore whether experiential knowledge should shy away from adopting professional terminology. Lastly, we will discuss the participants fear about losing autonomy together with the critical and transformative elements of experiential knowledge.

The participants expressed that they valued and appreciated all lived experiences. However, there were also suggestions that certain ‘filters’ needed to be applied when deciding who is representing and communicating experiential knowledge to health professionals. In practice, this meant that selected (and trained) patient representatives or professionals working for the organisations, were chosen to communicate experiential knowledge to wider audiences. Although the interviewees described experiential knowledge as all-encompassing and transformative, they expressed that some adjustments needed to be made in order to make it accessible to a professional audience. Blume (2017) has claimed that experiential knowledge has no ‘inherent authority’. This was reflected in the interviews, as the participants discussed ways in which experiential knowledge was communicated to health services and professionals. They argued that in order to permeate through to health services, experiential knowledge needed to be polished, audience friendly and clearly articulated:

I’ve been to lots of events where patients have given talks, which have been awful. So, we need to make sure that the people, who are experts of their own experience, and who we take along to give talks, know how to give them. […] And I know doctors who say that no one’s bothered to listen to the talks given by patients. And I get it. But then it also really annoys me, because there are really excellent ones too.

In the above extract, the participant talks about the difficulty of engaging health professionals. The interviewees provided many positive examples of successful collaboration with health services. Nevertheless, they also referred to instances where health professionals were dismissive or did not appreciate experiential knowledge. In the abstract below, the participant questions public health services promise of being user oriented. They also suggest that the inclusion of third sector organisations is vital as they can provide the “service users’ voice” and enable health services to live up to their promise.

I’ve noticed, in these meetings about the health and social care reform and such, that when they are really professionally orientated then they don’t take this [experiential views] seriously, which is really weird since this is the service users’ voice. This should carry the most weight on whether or not a service is working.

The participants also expressed fears that even though experiential knowledge was important, it would not reach its transformative potential, if it was not communicated effectively:

It’s not just about going somewhere to tell a story, which is so damn right and true since it’s based on lived experiences. But well, it works on some levels, but it doesn’t necessarily work if you want to be in there [health services] …influencing issues.

These partially self-imposed expectations also led to the organisations providing training, which prepared people with lived experiences to communicate with health professionals and even work in health services as experts by experience. During the training, personal experiences were processed and transformed into stories that could be used into develop services. Additionally, people attending the training could distance themselves from their personal experiences and adopt a stance that could be described as more neutral or even ‘professional’.

In my opinion the training is really important as you get to process your experience and how it links up with you being an expert by experience. And well, at the end of the day, I see it as a tool. Your experiences are something that you can place there and study. And they can provide some enjoyment, but in a neutral way. […] They [experiences] are almost like this coffee cup [on the table]. If they offer some help or are of benefit, then it’s damn good if they are of use to others. But it’s no longer about me being in the centre [of the experiences].

Despite experiential knowledge conveying vulnerability and emotion, people communicating the knowledge were expected to show a level of restraint and self-regulation. However, the idea that lived experiences needed to be more polished, structured and neutral in order to gain acceptance caused conflicting reactions. The interviewees were at times worried that the critical and countercultural aspects they attached to lived experiences would be lost. This could also lead to the loss of an authentic voice of experience if ways in which lived experiences were communicated began to include professional language or medical terminology:

P: Five or four years ago when I entered this scene, I heard these warnings that when we go into the system, then experts by experience are going to become poodles.

I: Well, that’s being suggested now and then…

P: Yeah.

I: Would it be the worst thing then…

P: Well, yes.

I: …that would automatically happen?

P: Yes. It’s true that the danger is that this old dominant culture will eat the counterculture. And then you start to imitate those [professionals] and like your language and everything, more or less, changes. And it’s cool and strokes the ego and so forth, but it’s not that simple. In my opinion that is also needed. But we need a wider scale of different approaches. That’s diversity. So in a way we are different parts of the same wave that is approaching and changing, making the revolution.

As the interviewee in the above extract explains, there were continuing concerns over the position and legitimacy of experiential knowledge. He also acknowledges a fear that by adopting too many professional traits and language, experiential knowledge could lose some of its authenticity and transformative power. The third sector organisations were trying to work collaboratively with health professionals and decision makers. They wanted to position themselves as knowledgeable and reliable partners that could bring new views and perspectives into health service development activities. Nevertheless, there were also fears that if they became too integrated and made too many adjustments, they could lose their autonomous position and the ability to voice critical views founded upon lived experiences.

Discussion and Conclusions

Health care has long been a contentious epistemological space, where questions about what is regarded as a valid form of knowledge for choices, and practices have been debated (Brosnan and Kirby 2016). Although patient-centredness and the importance of listening to patient experiences have been promoted through policies and health care strategies, experiential knowledge has not been able to fully establish its position as a legitimate form of knowledge to be used in decision making. The participants of this study were aware of this and provided arguments that supported the use of experiential knowledge and the value it could bring to health services. However, this study also highlights that organisations have varied definitions of what constitutes experiential knowledge, how it can be produced and how it should be communicated and used.

Experiential knowledge was described as consisting of embodied, social and emotional aspects of being ill and receiving treatment. It was described as ‘real’, authentic and transformative and thus uniquely different from medical and professional forms of knowledge as it was based on lived experiences and knowledge of the care system. It was not seen as narrow and specialised as professional knowledge. In many ways, the participants followed Borkman’s (1990) argument that experiential knowledge was not piecemeal or overly specialised but emerged as a result of numerous layered experiences of living with a problem. It as a unique form of understanding and the organisations played a role in the creation of this knowledge as they provided people with opportunities to meet and share their personal experiences, which were combined and ‘translated’ into practical insights and suggestions for service improvement. This resembles Caron-Flinterman et al. (2005) suggestion that experiential knowledge is produced by pooling together personal experiences. Nevertheless, the participants emphasised that this knowledge should not be used for tokenistic or ‘cosmetic’ purposes, but to inform and influence service delivery. This was highlighted in the descriptions of experiential knowledge as transformative, suggesting that its inclusion could revolutionise health services and decision making processes. The all-encompassing and transformative aspects also contained a suggestion that experiential knowledge has the potential to provide an alternative and critical perspective, which had been produced outside of health services by people who have historically been excluded from decision making. These factors also contributed to the idea that experiential knowledge was authentic, rooted in ‘real’ experiences, unlike professionals’ knowledge base that was constructed through learning.

Nevertheless, the participants identified different restrictions—or filters—that were placed on experiential knowledge. They described actions and choices that could lead to the taming of experiential knowledge and although they were partially due to the marginalised position of experiential knowledge within health care, the organisations also self-imposed certain filters. We will address the taming of experiential knowledge by relating it to issues around representation, language and autonomy. The participants offered varied and at times conflicting views on who could represent and communicate experiential knowledge to health professionals, managers and policymakers. Some expressed that it was people with lived experiences, who should be directly involved at all levels of health service development and delivery, as they could express experiential views authentically. By expressing these views, they aligned and positioned themselves as part of a much wider discussion and critique, which has emerged from feminist, queer, indigenous, disability, user/survivor and other social and academic movements regarding representation, and who is able to or has the right to act as the ‘voice’ of lived experience (Voronka 2016) and whether the representation of experiential knowledge or individual experiences by those who themselves lack them can lead to misrepresentation or even further marginalisation (Coles et al. 2013).

However, there were also suggestions that people who communicate experiential knowledge needed to be trained, and that they needed to be able to express views in a clear and concise manner. Hence, the organisations provided training that enabled people with lived experiences to process and structure their personal stories and provided them with communication skills. In some of the interview accounts, it was also suggested that some people are better at articulating experiential knowledge, and that they should be offered more opportunities than people who could not convincingly convey the message. Eriksson (2018) has argued that the tendency of organisations to individualise organisational-level patient involvement and request patients to relay personal experiences may downplay the role of the collective voice. These self-imposed rules and expectations on presentation could also exclude the views of certain groups or individuals, as Blume (2017) has highlighted that not everyone is equally able to articulate or utilise their experiences. Additionally, many of the organisations had employed paid members of staff, who did not have personal illness experiences, but acted as organisational representatives and voiced experiential knowledge to health services. The requirement to communicate effectively could be linked to the wider professionalisation of civil society that shifts focus onto accomplishment and effectiveness rather than the good will of ‘amateurs’ (Hustinx and Lammertyn 2003), who is this case could be the people with lived experiences who are untrained or unable to relay their knowledge clearly. This raises very different kinds of questions of who qualifies to represent experiential knowledge and whether these forms of taming lead to the exclusion of people who are unable or unwilling to act and communicate in the ‘correct’ way.

The issues raised above concerning representativeness and authenticity also relate to language, as the participants expressed that experiential knowledge should be communicated in language that was understandable, accessible and relatable. It should not contain too much medical or professional jargon. These ideas were linked to fears that the essence or authenticity of experiential knowledge would be lost if too many adjustments were made, and that experiential knowledge would be ‘colonised’ by medicine through professional language. Concurrently, there were worries that the organisations or experiential knowledge would not be taken seriously if they did not adapt professional ways of communicating. After all, knowledge that was deemed overly critical or completely incompatible with medical views may not be deemed worthy and authoritative by health professionals (Blume 2017). Both (Näslund et al. 2019) and Meriluoto (2018), who suggest that people with lived experiences are expected to position themselves as experts and adopt a ‘neutral’ stance. Although the interviewees argued that one of the main values of experiential knowledge was that it offers an insight into the everyday life of living with an illness, showing people as fragile and vulnerable, some adjustments needed to be made. It appears that when used in a health service environment, the communicator of experiential knowledge needed to adopt a more professional manner and learn to express affective issues in a neutral way.

Overall, it seemed that particularly the transformative aspects of experiential knowledge appeared to be under threat due to taming. Some of the participants saw the work of the organisations only as a part of a wider change or as one of the participants described the ‘official’ work done by the organisation as a contribution to a bigger wave that is making a revolution within health services. Although, all the organisations representing experiential knowledge can be seen as part of this wave, this study has highlighted that the wave contains conflicting approaches and interpretations of the different aspects of experiential knowledge and its’ uses in health services. Historically, service user movements in particular, have used experiential knowledge to challenge established medical knowledge. However, based on the results of this study and those of Näslund’s (2020), it seems that the organisations are using lived experiences, research evidence and clinical knowledge in combination. They are seen as complementary to each other and both organisations and individuals with lived experiences are taking a more concensus-oriented approach. Whether this reflects a more Nordic approach to involvement and experiential knowledge could be worth exploring further.

In this study, the organisations representing people with mental health problems were generally more likely to advocate for direct involvement that enabled people with lived experiences to communicate experiential knowledge. Amongst cancer organisations, the views were slightly more varied but there were no clear lines that could be drawn between organisations representing these different groups. The arguments and views expressed by participants were more likely to stem from the organisation’s own agenda and aims, rather than the specific illness groups they represented. Additionally, the findings underline the challenges organisations face as they attempt to balance between their different roles as ‘field experts’, supporters, service providers and representatives of experiential views, whilst concurrently being viewed as valued and legitimate collaborators by health professionals and policymakers. The role of third sector organisations as providers of experiential representation is an area of research that will surely resonate in several countries and service settings. Particularly, as collective forms of patient and public involvement have become commonplace in the health sector in several countries, and experiential knowledge is being acknowledged as a source of information (e.g. Castro et al. 2019). In the future, it is important to also explore how organisations and more informal patient networks that are not as closely engaged with health services, use experiential knowledge. In relation to health services, it is also interesting to further study how health professionals relate to experiential perspective, incorporate them to practice and deal with situations where experiential knowledge is used to openly challenge clinical perspectives.

References

Baggott, R., & Jones, K. L. (2018). Representing whom? UK health consumer and patient organisations in the policy process. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry, 15(3), 341–349.

Barbot, J. (2006). How to build an “active” patient? The work of AIDS associations in France. Social Science and Medicine, 62, 538–551.

Beresford, P. (2019). Public participation in health and social care: Exploring the co-production of knowledge. Frontiers in Sociology, 3, 41.

Blume, S. (2017). In search of experiential knowledge. Innovation: The European Journal of Social Science Research, 30(1), 91–103.

Boardman, Felicity K. (2014). Knowledge is power? The role of experiential knowledge in genetically ‘Risky’ reproductive decisions. Sociology of Health & Illness, 36(1), 137–150.

Boivin, A., Currie, K., Fervers, B., Gracia, J., James, M., Marshall, C., et al. (2010). Patient and public involvement in clinical guidelines: International experiences and future perspectives. Quality and Safety in Health Care, 19, e22.

Borkman, T. J. (1976). Experiential knowledge: A new concept for the analysis of selfhelp groups. Social Service Review, 50, 445–456.

Borkman, T. J. (1990). Experiential, professional and lay frames of reference. In T. J. Powell (Ed.), Working with selfhelp (pp. 3–30). Silver Spring: National Association of Social Workers Press.

Brosnan, C., & Kirby, E. (2016). Sociological perspectives on the politics of knowledge in health care: Introduction to themed issue. Health Sociology Review, 25(2), 139–141.

Brown, P., Zavestoski, S., McCormick, S., et al. (2004). Embodied health movements: New approaches to social movements in health. Sociology of Health & Illness, 26(1), 50–80.

Caron-Flinterman, J. F., Broerse, J. W. E., & Bunders, J. F. G. (2005). The experiential knowledge of patients: A new resource for biomedical research? Social Science and Medicine, 60, 2575–2584.

Castro, E. M., Van Regenmortel, T., Sermeus, W., & Vanhaecht, K. (2019). Patients’ experiential knowledge and expertise in health care: A hybrid concept analysis. Social Theory & Health, 17, 307–330.

Coles, S., Keenan, S., & Diamond, B. (2013). Madness contested: Power and practice. Ross-on-Wye: PCCS Books.

Daykin, N., Evans, D., Petsoulas, C., & Sayers, A. (2007). Evaluating the impact of patient and public involvement initiatives in the UK health services: A systematic review. Evidence & Policy, 3, 47–65.

Eriksson, E. (2018). Incorporation and individualization of collective voices: Public service user involvement and the user movement’s mobilization for change. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 29, 832–843.

Faulkner, A. (2017). Survivor research and Mad Studies: The role and value of experiential knowledge in mental health research. Disability & Society, 32(4), 500–520.

Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare’s specialist group for cancer. (2014). Syövän ehkäisyn, varhaisen toteamisen ja kuntoutumisen tuen kehittäminen vuosina 2014–2025. Kansallisen syöpäsuunnitelman II osa. [Development of cancer prevention, early detection and rehabilitative support 2014–2025. National Cancer Plan, Part II]. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-302-185-3 [retrieved: 19.3.2020]

Fredriksson, M., & Tritter, J. Q. (2017). Disentangling patient and public involvement in healthcare decisions: Why the difference matters. Sociology of Health & Illness, 39(1), 95–111.

Greenhalgh, T., Snow, R., Ryan, S., Rees, S., & Salisbury, H. (2015). Six “biases” against patients and carers in evidence-based medicine. BMC Medicine, 13(200), 1–11.

Hustinx, L., & Lammertyn, F. (2003). Collective and reflexive styles of volunteering: A sociological modernization perspective. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Non-profit Organizations, 14(2), 167–187.

Jones, M. (2018). Kokemustiedon määritykset ja käyttö julkisen terveydenhuollon kontekstissa. In J. Toikkanen & I. A. Virtanen (Eds.), Kokemuksentutkimus VI: kokemuksen käsite ja käyttö (pp. 169–190). Rovaniemi: Lapland University Press.

Jones, M., & Pietilä, I. (2018). “The citizen is stepping into a new role”—Policy interpretations of patient and public involvement in Finland. Health and Social Care in the Community, 26, e304–e311.

Jongsma, K. R., Nitzan, R.-Z., Raz, A. E., & Schicktanz, S. (2018). One for all, all for one? Collective representation in healthcare policy. Journal of Bioethical Enquiry, 15(3), 337–340.

Landzelius, K. (2006). Introduction: Patient organization movements and new metamorphoses in patienthood. Social Science and Medicine, 62, 529–537.

Mankell, A. N., & Fredriksson, M. (2020). Two-front individualization: The challenges of local patient organisations. Journal of Civil Society. https://doi.org/10.1080/17448689.2020.1721725.

Martin, G. (2008). ’Ordinary people only’: Knowledge, representativeness and the publics of public participation in healthcare. Sociology of Health & Illness, 30, 35–54.

Martin, G. P. (2012). Service users and the third sector: Opportunities, challenges and potentials in influencing the governance of public services. In M. Barnes & P. Cotterell (Eds.), Critical perspectives on user involvement (pp. 47–55). Bristol: Policy Press.

Mazanderani, F., Locock, L., & Powell, J. (2012). Being differently the same: The mediation of identity tensions in the sharing of illness experiences. Social Science & Medicine, 74(4), 546–553.

Meriluoto, T. (2018). Neutral experts or passionate participants? Renegotiating expertise and the right to act in Finnish participatory social policy. European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology, 5(1–2), 116–139.

Meyer, M. (2010). The rise of the knowledge broker. Science Communication, 32(1), 118–127.

Ministry of Social Affairs and Health (2011). Sosiaali- ja terveysalan kansalaisjärjestöt sosiaali- ja terveysministeriön kumppaneina. Sosiaali- ja terveysministeriön järjestöpoliittiset linjaukset 2011. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-00-3161-9 [retrieved: 19.3.2020]

Ministy of Social Affairs and Health (2019). Syöpäkeskus edistää yhdenvertaista hoitoa ja tutkimus- ja kehittämistoimintaa. https://stm.fi/syopakeskus [retrieved 19.3.2020]

Näslund, H. (2020). Collective deliberations and hearts on fire: Experiential knowledge among entrepreneurs and organisations in the mental health service user movement. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations. https://doi.org/10.1007/S11266-020-00233-6.

Näslund, H., Sjöström, S., & Markström, U. (2019). Service user entrepreneurs and claims to authority – a case study in the mental health area. European Journal of Social Work, 23(4), 1–13.

Noorani, T., Karlsson, M., & Borkman, T. (2019). Deep experiential knowledge: Reflections from mutual aid groups for evidence-based practice. Evidence & Policy, 15(2), 217–234.

Pavolini, E., & Spina, E. (2015). Users’ involvement in the Italian NHS: The role of associations and self-help groups. Journal of Health Organisation and Management, 29(5), 570–581.

Potter, J., & Wetherell, M. (1987). Discourse and social psychology: Beyond attitudes and behaviour. London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Prior, L. (2003). Belief, knowledge and expertise: The emergence of the lay expert in medical sociology. Sociology of Health & Illness, 25, 41–57.

Rabeharisoa, V., & Callon, M. (2004). Patients and scientists in French muscular dystrophy research. In S. Jasanoff (Ed.), States of knowledge. The co-production of science and social order (pp. 142–160). London: Routledge.

Rowland, P., McMillan, S., McGillicuddy, P., & Richards, J. (2017). What is “the patient perspective” in patient engagement programs? Implicit logics and parallels to feminist theories. Health, 21(1), 76–92.

Setälä, V., & Väliverronen, E. (2014). Fighting fat: The role of ‘field experts’ in mediating science and biological citizenship. Science as Culture, 23(4), 517–536.

Ternhag, A., Asikainen, T., & Giesecke, J. (2005). Size matters: Patient organisations exaggerate prevalence numbers. European Journal of Epidemiology, 20, 653–655.

Toiviainen, H. K., Vuorenkoski, L. H., & Hemminki, E. K. (2010). Patient organizations in Finland: Increasing number and great variations. Health Expectations, 13(3), 221–233.

Torjesen, D. O., Aarrevaara, T., Strangboli Time, M., & Tynkkynen, L.-K. (2017). The users’ role in primary and secondary healthcare in Finland and Norway. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 21(1), 103–122.

Van de Bovenkamp, H. M., Trappenburg, M. J., & Grit, K. J. (2010). Patient participation in collective healthcare decision making: The Dutch model. Health Expectations, 13(1), 73–85.

Vennik, F. M., Adams, S. A., Faber, M. J., & Putters, K. (2014). Expert and experiential knowledge in the same place: Patients’ experiences with online communities connecting patients and health professionals. Patient Education and Counseling, 95, 265–270.

Voronka, J. (2016). The politics of ‘people with lived experience’. Experiential authority and the risks of strategic essentialism. Philosophy, Psychiatry & Psychology, 23(3–4), 189–201.

Willis, K., Collyer, F., Lewis, S., Gabe, J., Flaherty, I., & Calnan, M. (2016). Knowledge matters: Producing and using knowledge to navigate healthcare systems. Health Sociology Review, 25(2), 202–216.

Winblad, U., & Ringård, Å. (2009). Meeting rising public expectations: The changing role of patients and citizens. In J. Magnussen, K. Vrangbaek, & R. B. Saltman (Eds.), Nordic health care systems: Recent reforms and current policy changes. Maidenhead: Open University Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jones, M., Jallinoja, P. & Pietilä, I. Representing the ‘Voice’ of Patients: How Third Sector Organisations Conceptualise and Communicate Experiential Knowledge in Health Service Development. Voluntas 32, 561–572 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-020-00296-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-020-00296-5