Abstract

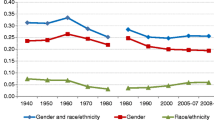

The aim of this paper is twofold: (a) to define a new concept, the welfare loss that a society experiences due to the segregation of the demographic groups that comprise it and (b) to propose measures that quantify this phenomenon satisfying a set of normative properties. In aggregating the well-being losses (gains) of the groups derived for being concentrated in low-status (high-status) organizational units, this paper embraces the distributive approach adopted in the literature on economic deprivation and poverty. The advantages of these measures are shown by exploring the welfare losses that the United States has experienced from 1980 to 2012 due to occupational segregation by both gender and race/ethnicity. Our analysis shows that our measures reveal certain aspects of the phenomenon that do not emerge when using overall segregation measures. Thus, for example, while nothing seems to have changed in U.S. labor market in the last decade according to some well-known overall segregation measures, the social welfare loss due to segregation has actually increased.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Throughout this paper, we will use the term well-being when referring to a group and social welfare when referring to society as a whole.

Philipson (1993) also explores the link between segregation and social welfare but he follows a different approach. He studies how individuals’ preferences should be for segregation measures being consistent with a social welfare criterion such as Pareto optimality.

Del Río and Alonso-Villar (2015) also deal with the consequences of the segregation of a group but assuming inequality neutrality rather than inequality aversion, the latter being the standard assumption when one aims at approaching well-being.

If occupations’ wages, \(w_{j}\), are measured by their average wages, \(\bar{w}\) will be equal to the average wage of the economy.

Loosely speaking, when assuming inequality aversion, we are assuming that the improvement of an individual who is in a better economic position than another does not increase the well-being index as much as it would do an improvement of the same magnitude experienced by the individual who is in a worse position.

Expression (2) can be generalized by defining a threshold \(z \ge 0\) which determines the level of losses that can be considered high enough so as to take them into account. Thus, we could define d i as follows:

$$d_{i} = \left\{ {\begin{array}{*{20}l} 0 \hfill & {{\text{if }}\left| {\hbox{min} \left\{ {\varPsi_{\varepsilon } (g^{i} ;t;w),0} \right\}} \right| \, \le {\text{ z}}} \hfill \\ {\left| {\varPsi_{\varepsilon } (g^{i} ;t;w)} \right|} \hfill & {{\text{if }}\left| {\hbox{min} \left\{ {\varPsi_{\varepsilon } (g^{i} ;t;w),0} \right\}} \right| \, > {\text{ z}}} \hfill \\ \end{array} } \right.$$The role played by z would be similar to that of the poverty line in poverty analyses: If \(z = 0\), all groups with losses, even if they were really small, would have a positive value of \(d_{i}\); if \(z > 0\) only the groups whose losses were above that threshold would be considered in the analysis.

Similar curves have been proposed in the field of wage discrimination, where they are labeled as inverse generalized Lorenz curves for distribution of wage gaps (Jenkins 1994) and discrimination curves (Del Río et al. 2011), and also in the field of unemployment, where they are labeled duration profiles (Shorrocks 2009).

If \(\tilde{d}\) and \(\tilde{d}'\) have a different dimension, \(\tilde{d}\) will necessarily differ from \(\tilde{d}'\) and its replications.

Note that when two WLAS curves do not cross, it is possible to determine the range of \(z \ge 0\) values associated with the dominated distribution for which the dominance relationship is kept (see footnote 6). By doing so, one could incorporate a certain degree of cardinality in the analysis without using indices.

Examples of these indices are: the Sen–Shorrocks–Thon index, the Hagenaars index, the Watts index, and the Clark–Hemming–Ulph–Chakraverty family of indices (see Foster et al. 2013).

Remember that vector \(\tilde{d}\) is ranked from high to low losses.

Another way to incorporate groups with \(\varPsi_{\varepsilon } > 0\) in empirical analyses is to use inequality measures that allow working with negative and positive well-being values simultaneously, thus quantifying the degree of inequality between both types of groups.

There is no information about occupations in the decennial censuses from 2000 onward; the ACS is the nationwide survey, also provided by the Census Bureau, which replaced the decennial census long form and that includes occupation. The 5-year sample that we use, which considers the two years before and after 2010, accounts for 6.9 million workers. The number of workers in the sample for 1980 is about 5 million, roughly 5.8 million for 1990, and 6.4 million for 2000. The number of observations of each group in the sample is given in “Table 1 in the Appendix”.

In any case, the harmonization process involved several adjustments which imply that the classification has some empty employment occupations in several years. The real number of occupations in 1980, 1990, 2000, and 2008–2012 are, respectively, 382, 384, 337, and 333. Fortunately, the majority of the empty occupations have a low employment in the years in which they appear.

The residual category “other race” is different each year. In particular, multiple-race responses were allowed since 2000.

For each occupation, we trim the tails of the hourly wage distribution to prevent data contamination from outliers. Thus, we compute the trimmed average in each occupation eliminating all workers whose wage is either zero or situated below the first or above the 99th percentile of positive values in that occupation.

When using \(\varepsilon = 2\), we also find that the WLAS curve of 1980 is dominated by those of 1990 and 2000, and crosses that of 2008–2012 (the latter is dominated by that of 2000). The results for \(\varepsilon = 0\) are similar, except that the WLAS curve of 1980 crosses that of 2000 (apart from crossing that of 2008–2012). In addition, we see that since 1990, each WLAS curve is dominated by that of the previous decade, which means that there is an undisputed deterioration between 1990 and 2008–2012, decade by decade. These charts are not included in the document.

We use multigroup segregation measures because we have 12 gender-race/ethnicity groups.

Note that this is not the case here since the segregation of some groups has actually changed (Del Río and Alonso-Villar 2015).

Remember that, in our case, the “income” of an individual, s, is the relative wage of the occupation, j, in which this individual works: \(y_{s} \equiv \left( {\frac{{w_{j} }}{{\bar{w}}}} \right)\).

References

Allard, M. (2011). Asians in the U.S. labor force: Profile of a diverse population. Monthly Labor Review, 134(11), 3–22.

Alonso-Villar, O., & Del Río, C. (2010). Local versus overall segregation measures. Mathematical Social Sciences, 60, 30–38.

Alonso-Villar, O., & Del Río, C. (2016). Occupational segregation and well-being. Review of Income and Wealth. doi:10.1111/roiw.12224.

Alonso-Villar, O., & Del Río, C. (2017). The occupational segregation of African American women: Its evolution from 1940 to 2010. Feminist Economics, 23(1), 108–134.

Alonso-Villar, O., Del Río, C., & Gradín, C. (2012). The extent of occupational segregation in the United States: Differences by race, ethnicity, and gender. Industrial Relations, 51(2), 179–212.

Atkinson, A. B. (1970). On the measurement of inequality. Journal of Economic Theory, 2(3), 244–263.

Atkinson, A. B. (1987). On the measurement of poverty. Econometrica, 55, 749–764.

Blau, F. D., Brummund, P., & Liu, A. (2013). Trends in occupational segregation by gender 1970–2009: Adjusting for the impact of changes in the occupational coding system. Demography, 50, 471–492.

Blau, F. D., & Kahn, L. M. (2016). The gender wage gap: Extent, trends, and explanations. NBER Working Paper 21913.

Browne, I., & Misra, J. (2003). The intersection of gender and race in the labor market. Annual Review of Sociology, 29, 487–513.

Collins, P. H. (1999). Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness and the politics of empowerment. London: HarperCollins.

Cowell, F. A. (2011). Measuring inequality. London school of economics perspectives in economic analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Darity, W. A., Jr. (2005). Stratification economics: The role of intergroup inequality. Journal of Economics and Finance, 29(2), 144–153.

Darity, W. A., Jr., Hamilton, D., & Stewart, J. B. (2015). A tour de force in understanding intergroup inequality: An introduction to stratification economics. Review of Black Political Economy, 42, 1–6.

Darity, W. A., Jr., & Mason, P. L. (1998). Evidence on discrimination in employment: Codes of color, codes of gender. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 12(2), 63–90.

Davis, J. B. (2014). Stratification economics and identity economics. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 39(5), 1215–1229.

Del Río, C., & Alonso-Villar, O. (2012). Occupational segregation measures: A role for status. Research on Economic Inequality, 20, 37–62.

Del Río, C., & Alonso-Villar, O. (2015). The evolution of occupational segregation in the U.S., 1940–2010: The gains and losses of gender-race/ethnic groups. Demography, 52(3), 967–988.

Del Río, C., Gradín, C., & Cantó, O. (2011). The measurement of gender wage discrimination: The distributional approach revisited. Journal of Economic Inequality, 9, 57–86.

Duncan, O., & Duncan, B. (1955). A Methodological analysis of segregation indexes. American Sociological Review, 20(2), 210–217.

Foster, J. E., Greer, J., & Thorbecke, E. (1984). A class of decomposable poverty measures. Econometrica, 52(3), 761–766.

Foster, J. E., Greer, J., & Thorbecke, E. (2010). The Foster–Greer–Thorbecke (FGT) poverty measures: 25 Years later. Journal of Economic Inequality, 8, 491–524.

Foster, J. E., López-Calva, L. F., & Szekely, M. (2005). Measuring the distribution of human development: Methodology and an application to Mexico. Journal of Human Development, 6(1), 5–29.

Foster, J. E., Seth, S., Lokshin, M., & Sajaia, Z. (2013). A unified approach to measuring poverty and inequality. Theory and practice. Washington D.C.: The World Bank.

Foster, J. E., & Shorrocks, A. (1988). Poverty orderings. Econometrica, 56, 173–178.

Frankel, D. M., & Volij, O. (2011). Measuring school segregation. Journal of Economic Theory, 146(1), 1–38.

Glenn, E. N. (1999). The social construction and institutionalization of gender and race: An integrative framework. In M. M. Ferree, J. Lorber, & B. B. Hess (Eds.), Revisioning gender (pp. 3–43). Thousand Oaks (CA): Sage publications.

Gradín, C. (2013). Conditional occupational segregation of minorities in the US. Journal of Economic Inequality, 11(4), 473–493.

Gradín, C., del Río, C., & Alonso-Villar, O. (2015). Occupational segregation by race and ethnicity in the US: Differences across states. Regional Studies, 49(10), 1621–1638.

Hao, L., & Fong, E. (2011). Linking dichotomous segregation with multi-group segregation: Weighted segregation ratios in selected U.S. metropolitan areas. Social Science Research, 40, 379–391.

Hegewisch, A., Liepmann, H., Hayes, J., & Hartmann, H. (2010). Separate and not equal? Gender segregation in the labor market and the gender wage gap. Washington, D.C.: Institute for Women’s Policy Research Briefing Paper.

Hsieh, C.-T., Hurst, E., Jones, C. I., & Klenow, P. J. (2013). The allocation of talent and U.S. economic growth. NBER Working Paper 18693.

Huffman, M. (2004). More pay, more inequality? The influence of average wage levels and the racial composition of jobs on the Black–White wage gap. Social Science Research, 33, 498–520.

Hutchens, R. M. (2009). Occupational segregation with economic disadvantage: An investigation of decomposable indexes. Research on Economic Inequality, 17, 99–120.

Iceland, J. (2004). Beyond Black and White metropolitan residential segregation in multi-ethnic American. Social Science Research, 33, 248–271.

Jenkins, S. P. (1994). Earnings discrimination measurement. A distributional approach. Journal of Econometrics, 61, 81–102.

Jenkins, S. P., & Lambert, P. J. (1993). Poverty orderings, poverty gaps, and poverty lines. University of Wales Swansea Economics Discussion Paper 93-07.

Jenkins, S. P., & Lambert, P. J. (1997). Three ‘I’s of poverty curves, with an analysis of UK poverty trends. Oxford Economic Papers, 49, 317–327.

Jenkins, S. P., & Lambert, P. J. (1998). Three ‘I’s of poverty curves and poverty dominance: TIPs for poverty analysis. Research on Economic Inequality, 8, 39–56.

Kaufman, R. L. (2010). Race, gender, and the labor market: Inequalities at work. Boulder, Colorado: Lynne Rienner Publishers.

King, M. (1992). Occupational segregation by race and sex, 1940–1988. Monthly Labor Review, 115, 30–37.

Kurtulus, F. (2012). Affirmative action and the occupational advancement of minorities and women during 1973–2003. Industrial Relations, 51, 213–246.

Lambert, P. J. (1993). The distribution and redistribution of income. A mathematical analysis. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Mintz, B., & Krymkowski, D. (2011). The intersection of race/ethnicity and gender in occupational segregation. International Journal of Sociology, 40(4), 31–58.

Paul, S. (1992). An illfare approach to the measurement of unemployment. Applied Economics, 24, 739–743.

Philipson, T. (1993). Social welfare and measurement of segregation. Journal of Economic Theory, 60, 322–334.

Reardon, S. F. (2009). Measures of ordinal segregation. Research on Economic Inequality, 17, 129–155.

Reardon, S. F., & Firebaugh, G. (2002). Measures of multigroup segregation. Sociological Methodology, 32, 33–76.

Reskin, B., & Bielby, D. (2005). A sociological perspective on gender and career outcomes. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(1), 71–86.

Reskin, B., Hargens, L., & Hirsh, E. (2004). Picturing segregation: The structure of occupational segregation by sex, race, ethnicity, and hispanicity. Washington: Mimeo, University of Washington.

Ruggles, S., Alexander, T., Genadek, K., Goeken, R., Schroeder, M., & Sobek, M. (2010). Integrated public use microdata series: Version 5.0 [machine-readable database]. Minneapolis, MN: Minnesota Population Center.

Sen, A. K. (1976). Poverty: An ordinal approach to measurement. Econometrica, 44, 219–231.

Sengupta, M. (2009). Unemployment duration and the measurement of unemployment. Journal of Economic Inequality, 7, 273–294.

Seth, S. (2009). Inequality, interactions, and human development. Journal of Human Development and Capabilities, 10(3), 375–396.

Shorrocks, A. (1998). Deprivation profiles and deprivation indices. In S. P. Jenkins, A. Kapteyn, & B. M. S. van Praag (Eds.), The distribution of house welfare and household production (pp. 250–267). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Shorrocks, A. (2009). On the measurement of unemployment. Journal of Economic Inequality, 7(3), 311–327.

Silber, J. (1992). Occupational segregation indices in the multidimensional case: A note. The Economic Record, 68, 276–277.

Silber, J. (2012). Measuring segregation: Basic concepts and extensions to other domains. Research on Economic Inequality, 20, 1–35.

Spencer, B. D., & Fischer, S. (1992). On comparing distributions of poverty gaps. Sankhyā: The Indian Journal of Statistics, series B (1960–2002), 54(1), 114–126.

Spriggs, William E., & Williams, Rhonda M. (1996). A logit decomposition analysis of occupational segregation: Results for the 1970s and 1980s. Review of Economics and Statistics, 78, 348–355.

Wang, Q. (2004). Labor market concentration of Asian ethnic groups in US metropolitan areas: A disaggregated study. Population, Space and Place, 10, 479–494.

Watts, M. (1995). Trends in occupational segregation by race and gender in the U.S.A., 1983–1992: A multidimensional approach. Review of Radical Political Economics, 27(4), 1–36.

Zheng, B. (1997). Aggregate poverty measures. Journal of Economic Surveys, 11(2), 123–162.

Acknowledgements

Funding was provided by the Ministerio de Economía, Industria y Competitividad (Grant No. ECO2014-52616-R), the Agencia Estatal de Investigación and Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional (Grant No. ECO2016-76506-C4-2-R), and Xunta de Galicia (Grant No. GRC 2015/014). We also want to thank Francesco Andreoli and the reviewers for helpful comments).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

1.1 Assumptions Behind the Indices Proposed by Alonso-Villar and Del Río (2016)

As mentioned in Sect. 2.1, the properties these authors assume on the SWF are standard: this function is individualistic, strictly increasing, symmetric, and additive. The first property means that the SWF depends on individuals’ utilities and on nothing else. Individuals’ preferences are also assumed to be individualistic and, therefore, the utility level of each individual only depends on her/his own “income”. Strictly increasing monotonicity entails that the social welfare increases when, ceteris paribus, any individual’s “income” rises. Symmetry means individuals play identical roles. Additivity implies that the SWF can be expressed as the summation of individuals’ utilities which, as mentioned above, only depends on her/his “income”Footnote 23:

Requiring these properties imply that the individuals’ utility function is shared by all of them. Thus, \(U_{s} = U, \, \forall s\). This utility function, U(·), is also assumed to be strictly concave—which is also a standard condition—so that an increase in an individual’s relative wage, all else equal, entails a larger change in U (and, therefore, in SWF) the lower the initial relative wage of that individual is. In addition, \(U' = {{\partial U({{w_{j} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{w_{j} } {\bar{w}}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\bar{w}}})} \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{\partial U({{w_{j} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{w_{j} } {\bar{w}}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\bar{w}}})} {\partial ({{w_{j} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{w_{j} } {\bar{w}}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\bar{w}}})}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\partial ({{w_{j} } \mathord{\left/ {\vphantom {{w_{j} } {\bar{w}}}} \right. \kern-0pt} {\bar{w}}})}}\) is assumed to have constant elasticity, given by the parameter ε, so that if an individual’s relative wage increases by 1%, then U’ drops by ε % no matter her/his initial relative wage level. This parameter reflects how sharply curved function U is and, by expression (5), how sharply curved function SWF is. Therefore, it can be interpreted as a (relative) inequality aversion parameter. If we think of U as a “social utility function” rather than as standard utility function, ε shows the rate at which the weight of each individual in the social welfare decreases as her/his income increases. The assumption of constant (relative) inequality aversion is also often used in the literature on income inequality.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

del Río, C., Alonso-Villar, O. Segregation and Social Welfare: A Methodological Proposal with an Application to the U.S.. Soc Indic Res 137, 257–280 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1598-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-017-1598-0