Abstract

This paper investigates the relationship between public subsidies and firm innovation in transition and developing economies, which are likely to have less developed financial markets. Innovation includes the introduction of new products or services and the upgrade of existing ones, which is of particular relevance for these economies. The results obtained using alternative measures of financial constraints and market competition, within a range of econometric techniques, suggesting a positive relation between public subsidies and the innovative activities of 11,998 firms across 30 Eastern Europe and Central Asian countries. This correlation is stronger for firms more likely to be financially constrained.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Innovation is regarded as an important driving element of firm-level productivity, competitiveness and growth. Equally largely accepted is the view that innovative activities are difficult to finance due to imperfect capital markets. A large strand of literature highlights that firm innovative activities are likely to be more severely affected by financial constraints than fixed capital investment due to the higher complexity, specificity and degree of uncertainty characterising innovation projects. Studies in this literature stream have focused on the role played by internal finance (Himmelberg and Petersen 1994; Mulkay et al. 2001), cost and availability of external funding (Hall 2002; Brown et al. 2012) and overall country financial development (Hsu et al. 2014) for R&D investment.

As government intervention has become common practice to support private innovative activities in most industrialised countries, another strand of literature has developed to investigate whether subsidies have additional effects or else they merely replace private funding of given R&D investments.Footnote 1 Hall and Lerner (2010) find limited evidence to support the effectiveness of US government programmes, but other studies based on European countries data link public subsidies with increased firm innovative activities.Footnote 2

This paper is related to both strands of literature. Using firm-level data, the analysis focuses on the role of public subsidies for the innovative activities of firms in emerging market economies, which has been the object of less scrutiny so far. Furthermore, emphasis is put on the interaction between public subsidies and firm financial constraints. As capital markets in emerging countries are less mature, firms’ investment in innovative activities is likely to be more severely affected by financial constraints relative to the innovative investment of firms in developed economies (Erol 2005; Brown et al. 2011). Although mainly in the form of imitation (i.e., new-to-firm innovation), innovation is as important for the economic growth of these countries as new-to-world innovations.Footnote 3 Therefore, assessing whether public subsidies effectively stimulate innovation by alleviating firm financial constraints becomes crucial. If so, public intervention targeting financial sector development and innovation policy may help hasten economic growth in emerging economies.

This paper uses a cross-country data set drawn from the Business Environment and Enterprise Performance Survey (BEEPS), which provides rich information on innovation and finance for 11,998 enterprises in 30 countries of Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Firm innovation is defined broadly to include the introduction of new products or services and upgrading an existing product line service, which is of great relevance for firms in emerging countries. Gorodnichenko and Schnitzer (2013) and Ayyagari et al. (2011) use similarly defined firm innovation indicators and focus on the role of financial factors in such countries. These studies do not consider, however, the role of subsidies for firm innovation. With few exceptions (e.g. Hyytinen and Toivanen 2005; Aerts and Schmidt 2008; Paunov 2012), the R&D subsidy literature contrasts the innovative behaviour of subsidised and unsubsidised firms without taking into account their financial strength. This paper aims to find whether subsidies facilitate innovation via ameliorating firm financial constraints.

Detailed information in the BEEPS survey allows us to construct several alternative indicators of firm financial strength based on objective measures of internal financial resources, access to and use of external funding as well as responses regarding the difficulty of access to external finance, which could be an obstacle to firm development and operations. The analysis controls for various factors affecting firm innovation, including indicators of product market competition (Beneito et al. 2015). The empirical results suggest a positive relationship between firm innovation and receipt of public subsidies. Additional tests delving deeper in the data indicate that the relationship is stronger for financially constrained firms. Exploiting the cross-country variation in the data, the analysis is conducted also separately on samples according to country EU membership at the time the information was collected in the 2009 BEEPS survey.Footnote 4 Our empirical findings suggest that subsidies have a stronger impact on alleviating financial constraints for firms in non-EU countries, which are likely to have less developed financial markets than EU economies.Footnote 5

The empirical results are robust to a range of tests. Firstly, using alternative measures of firm financial strength and a variety of controls leave the results unchanged. Secondly, the results are robust to the choice of estimator. Instrumental variables techniques, including the newly developed special regressor estimator (Lewbel 2000), deal with the potential endogeneity of self-reported financial constraints. Finally, treatment effects and propensity score matching techniques address the potential selection bias in that R&D-intensive firms may be more likely to apply for a subsidy.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 briefly reviews the two strands of the literature this paper is related to. Section 3 outlines the empirical strategy. Section 4 presents the data and gives some summary statistics. Section 5 reports the empirical results and the final section concludes.

2 Literature review

This section reviews the two strands of the innovation literature: one focusing on firm financial strength and the other investigating the role of public subsidies. Finally, it mentions the few papers controlling for both firm financial strength and availability of public subsidies.

2.1 Financial constraints and innovation

The importance of binding financial constraints for firm innovative activities has long been acknowledged in the literature. In a seminal paper, Fazzari et al. (1988) established that the sensitivity of firms’ investment to cash flow fluctuations reveals the presence of financing constraints for firms.Footnote 6 Kaplan and Zingales (1997) challenged their approach on the grounds that investment-cash flow sensitivities need not increase monotonically with financial constraints and that investment opportunities may not be sufficiently controlled for. The subsequent long debate has prompted the literature to consider alternative proxies for firm wealth and different ways of identifying how financing constraints may impact firm activities such as growth, fixed capital investment, inventory accumulation and R&D expenditure.

Several studies emphasising the role of internal finance for firm R&D investment, use panel data and employ an instrumental variable approach to control for the endogeneity of cash flow. Among others, Himmelberg and Petersen (1994) find a significant cash flow effect in their panel of small US firms in high-tech industries; Mulkay et al. (2001) compare the cash flow sensitivity of R&D investment in a dynamic setting for firms in USA versus France.

Recent studies have suggested ways to circumvent the drawbacks related with the use of cash flow as a measure of internal resources. Czarnitzki and Hottenrott (2011a, b) propose using the empirical price-cost margin. Brown et al. (2012) advocate the use of cash holdings, instead of cash flow, as it more accurately incorporates firm R&D smoothing behaviour in response to high adjustment costs. Aghion et al. (2012) propose a payment incident variable as an indicator of firm credit constraints. They find that French firms’ R&D investment is negatively correlated with supplier overdue payments and the effect is stronger in sectors more dependent on external finance.

Kim and Weisbach (2008) suggest equity plays an important role in raising capital for R&D spending. Brown and Petersen (2009) and Brown et al. (2012) estimate dynamic panel models and confirm the linkage between stock issues and R&D investment of US and European firms, respectively. Using panel data for 32 countries, Hsu et al. (2014) show that overall market capitalization encourages innovation productivity (as measured by patenting).

Debt finance may not be the preferred source for financing innovation due to the high complexity, specificity, degree of uncertainty and limited collateral value characterising innovation projects.Footnote 7 Hall (2002) reports that R&D-intensive firms normally exhibit lower debt ratios than firms engaging less in R&D. Similarly, Brown et al. (2012) find weak debt finance effects on the R&D investment of US quoted firms. On the contrary, using cross-sectional survey data, Ayyagari et al. (2011) find a positive relation between access to external financing, most likely bank financing and the extent of firm innovation in emerging economies.

Firm-level survey data regarding cost and availability of finance facilitates construction of alternative direct measures of financial constraints. For example, Canepa and Stoneman (2008) link (lack of) availability of finance with the likelihood that firms from high-tech industries and small firms in the UK report a project being abandoned or delayed. Hajivassiliou and Savignac (2016) study whether French firms’ innovative projects were delayed, abandoned or non-started due to one of the following reasons: unavailability of new financing, searching and waiting for new financing or too high cost of finance. Using responses to questions on how severe an obstacle is access to and cost of external funding for business operations, Gorodnichenko and Schnitzer (2013) show that firms’ decisions to invest in innovative activities are sensitive to financial frictions.

2.2 Subsidies and innovation

Government support of R&D is rooted in the idea of market failures that lead to private underinvestment in R&D. This can be due to private R&D investments not being able to fully appropriate all benefits as other companies may free ride and benefit from innovations. R&D underinvestment may also occur due to imperfect capital markets which hinder the financing of socially desirable projects. Governments should then support those projects that are socially beneficial and would not be carried out in the absence of a subsidy. If public funding merely replaces (crowds out) private funding, no additional R&D investments are generated.

The impact of public subsidies on firm innovation has attracted much interest in the literature. Overall, the empirical literature concludes against public subsidies completely crowding out private investment. Despite finding crowding out effects, Wallsten (2000) cannot rule out that the US SBIR grants allowed firms to continue their R&D activities at a constant level rather than cutting back. A series of papers use cross-sectional survey data for European countries and conduct a treatment effect analysis. Evidence that public support stimulates private R&D investment is found for firms in East Germany (Almus and Czarnitzki 2003), Finland (Czarnitzki et al. 2007) and Flanders and Germany (Aerts and Schmidt 2008; Czarnitzki and Lopes-Bento 2013, 2014; Hottenrott and Lopes-Bento 2014).

Panel data studies generally find some crowding in effects. For instance, Lach (2002) reports substantial stimulation of the own R&D spending of small Israeli firms. Girma et al. (2007) show that only grants supporting productivity-enhancing activities increase total factor productivity of Irish plants. Similarly, Colombo et al. (2011) analyse 247 new technology-based Italian firms to find that only subsidies provided on a competitive basis have large positive effects on firm TFP growth. Distinguishing between research and development grants, Hottenrott et al. (2014) find evidence of both direct and cross-scheme effects and the magnitude of the treatment effects depends on firm size and age.

Takalo et al. (2013a) model the subsidy application and R&D investment decisions of the firm and also the subsidy granting decision of the public agency in charge of the program to estimate the expected welfare effects of targeted R&D subsidies using project level data from Finland. Allowing for both fixed and sunk costs affecting firms’ R&D participation and continuation decision, Arque-Castells and Mohnen (2015) show that subsidy policies may have long lasting effects. Their dynamic additionality prediction finds support in empirical results obtained on a panel of Spanish manufacturing firms: subsidy policies may affect both the number of R&D firms and intensity.

While the subsidy literature focuses on developed economies, there is evidence pointing towards the importance of state programs in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Among others, Ginevičius et al. (2008) stress that the intensity of the state aid (the share of project value) and not the absolute amount significantly influences firm innovation in Lithuania. Aubakirova (2014) shows that participation in state programs is considered to be one of the real chances to strengthen financial stability and growth of the innovation activity in Kazakhstan. Using 2015 survey data from 263 Polish firms in high-tech industries, Wach (2016) concludes that policy makers should continue to support especially highly innovative industries.

Governments may also offer loans or tax credits to foster private sector R&D. Similar to subsidies, several studies have scrutinised whether tax credits affect firm R&D expenditure. Kobayashi (2014) finds that R&D tax credits induce an increase in Japanese SMEs’ R&D expenditures and the effect is larger for liquidity-constrained firms. However, Cowling (2016) and Busom et al. (2014, 2016) do not think that tax credits significantly affect SME’s R&D in the UK and Spain, respectively. Relative to subsidies, tax credits eliminate potential government preference with respect to industry and the type of the firm. In order to benefit from tax incentives, firms have to first fund R&D projects that comply with the government’s definition of R&D. Therefore, firms facing financial constraints are less likely to benefit from tax credits than from subsidies. This is likely to be particularly relevant for firms in countries with less-developed financial markets. Our analysis does not consider R&D tax incentives due to data unavailability and the absence of this policy instrument in many of the Eastern Europe and Central Asia countries in our sample.Footnote 8

Czarnitztki et al. (2015) model the behaviour of firms in four alternative scenarios: a subsidy regime, a tax credit policy, no public support and a European-wide agency deciding on subsidies. Using project-level data for Flanders, Germany and Finland, their study finds larger welfare effects from an EU innovation policy due to cross-country spillovers.

2.3 Subsidies, financial constraints and innovation

A handful of papers take into account capital market imperfections when studying the effects of subsidies on firm innovation. Hyytinen and Toivanen (2005) show that government funding disproportionately affected the R&D expenditure of Finnish SME firms operating in industries dependent on external finance, pointing out to a crowding out effect. However, Aerts and Schmidt (2008) control for firm financial strength (cash flow for Flanders and a four-point Likert scale for Germany) and reject the hypothesis that public R&D subsidies crowd out private R&D investment in their samples.

Takalo et al. (2013b) model the interaction between public and private financiers of firm R&D and show that higher costs of external finance increase (decrease) the optimal subsidy rate at the extensive (intensive) margin. Finding evidence of subsidy additionality crucially depends on the size of subsidy spillover effects.

Brzozowski and Cucculelli (2016) use cross-sectional data on over 13,000 firms in seven European countries (Austria, France, Germany, Hungary, Italy, Spain and UK) to analyse the impact of the financial crisis on firm innovative behaviour. Their results suggest that firms with prior access to credit, who have benefited from public support to investment in 2007–2009, are more likely to expand their product offer. Paunov (2012) analyses firms’ innovation performance during the financial crisis in eight Latin American countries. Controlling for access to external funding, Paunov (2012) shows that manufacturing firms with access to public funding were less likely to discontinue innovation projects in 2008–2009.

3 Empirical strategy

Our empirical strategy bridges the analysis in the firm financial strength stream (e.g. Gorodnichenko and Schnitzer 2013; Ayyagari et al. 2011), with the approach in the R&D subsidy literature (e.g. Aerts and Schmidt 2008; Czarnitzki and Lopes-Bento 2013), to account for the role of public subsidies on firm innovative activities. The baseline empirical model specifies firm innovative activities as a function of subsidies received, firm financial strength, firm R&D effort and other controls:

where i indexes firms. The dependent variable Innovate i is a generic dichotomous variable equal to 1 if the firm reports an innovative activity, 0 otherwise. Subsidy i indicates receipt of a subsidy, FS i measures firm financial strength and R&D i records whether the firm invested in R&D. The control X i consist of various factors thought to affect firm innovative activities, such as firm size and age, foreign capital, export status and industry and country characteristics. Detailed description of all the variables is provided in the data section below.

Benefiting from rich firm financial information, this study uses accounting data-based indicators for access to external funding (like Ayyagari et al. 2011; Paunov 2012) and for availability of internal finance (as in Brown et al. 2012)), as well as direct measures of financial constraints reported by firms (similar to Aghion et al. 2012; Gorodnichenko and Schnitzer 2013). The use of alternative measures facilitates comparison with the extant literature, exploits the advantages brought by each approach and helps reduce concerns about the appropriateness of the financial constraints indicators used in this study.

The multivariate analysis starts with the estimation of simple probit models. An instrumental variable approach (both probit and a special regressor) deals with potential concerns regarding endogeneity of financial variables. A matching estimator addresses the potential sample selection bias in receiving subsidies, as routinely done by the subsidies strand of the innovation literature. Even though it does not establish a causal relationship, through the variety of controls and estimation techniques, this study assesses the links between innovation, public subsidies, firm financial health and input in innovation.

4 Data and summary statistics

4.1 Sample

The data used in this study is drawn from the Business Environment and Enterprise Performance Survey (BEEPS), a joint initiative of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) and the World Bank. BEEPS is a particularly rich data set covering a broad range of business environment topics including innovation, access to finance, trade, competition and performance measures. The cross-sectional analysis in this study uses the fourth round of the survey, 2009 BEEPS.Footnote 9 Starting with 2008, the survey underwent changes in the questionnaire and methodology which aimed to improve cross-country comparability and to make it compatible with the Enterprise Surveys the World Bank has been implementing in other regions of the world since 2006. Earlier rounds of BEEPS have been used by Brown et al. (2011), Gorodnichenko and Schnitzer (2013), Popov (2013), Hanedar et al. (2014), while Ayyagari et al. (2011) use the 2006 World Bank Enterprise Surveys.

Since 2008, the survey universe consist of the majority of manufacturing sectors (excluding extraction), retail trade, construction and most services sectors (wholesale, hotels, restaurants, transport, storage, communications, IT).Footnote 10 Only registered companies with at least five employees are eligible for interview but there are no restrictions on firm age. Firms with 100% government/state ownership are no longer eligible to participate. In contrast to previous rounds of BEEPS, there are no additional requirements on the ownership, exporter status, location or years in operation of the establishment. Starting with the fourth round, BEEPS uses three instruments: the manufacturing, the retail and the core (residual sectors) questionnaire. Although many questions overlap, some are asked only to one type of business (e.g. retail firms are not asked questions about capacity utilisation).

BEEPS strive to provide a representative sample of a country’s private sector in terms of economic sectors, firm size and region distribution. The 2009 BEEPS covered 11,998 firms in 30 countries of Eastern Europe and Central Asia. Appendix Table 12 provides the structure of the sample by country (panel A) and by main industry groups (panel B).

A. Innovative activities

The generic outcome variable Innovate denotes, alternatively, several variables derived from questions regarding firm innovative activities. NewProduct is a binary variable equal to 1 if the firm answered “yes” (0 if it answered “no”) to the following question: “In the last three years, has this establishment introduced new products or services?”. Upgrade is constructed similarly if the firm upgraded an existing product line or service in the previous three years. The BEEPS questions align closely with the definition in the Oslo Manual (OECD 2005) developed by OECD and Eurostat for innovation surveys. Gorodnichenko and Schnitzer (2013) analyse similarly defined variables using earlier rounds of BEEPS. In their UK SMEs analysis, Lee et al. (2015) also define innovators as those firms which have introduced a new product in the previous 12 months.

Even though 2009 BEEPS does not include information regarding the introduction of new technologies, NewProduct and Upgrade provide a good reflection of firm innovation in the BEEPS sample since these are the most common innovative activities undertaken by firms in emerging economies. Ayyagari et al. (2011) identify eight firm innovative activities using responses to similar questions in the Enterprise Surveys of the World Bank and observe that a higher percentage of firms are more actively engaged in core innovation (introduced a new product line, upgraded existing product lines) than in other innovative activities.

Additionally, BEEPS 2009 asks businesses whether they have contracted with other companies (outsourced) activities previously performed in-house or have discontinued at least one product or service in the last 3 years. Responses to these questions are coded 1–0 (yes-no) to create two more variables, Outsource and Discont. Only manufacturing firms are asked the question on outsourcing. On the contrary, all firms are asked whether they discontinued at least one product line or service in the last 3 years. One could argue though that this is not a measure of innovation but rather a measure of firm flexibility and dynamism (Ayyagari et al. 2011). Notwithstanding their weaknesses, these two variables are used to complement the firm innovation analysis in additional tests.

Besides information about the outcome of innovative activities, the survey provides data on whether firms had any (in-house or outsourced) R&D expenditure in 2007. Even though R&D expenditure does not necessarily lead to innovation, it provides a good measure of firm innovation input.Footnote 11 The variable R&D, equal to 1 if the firm spent a positive amount on R&D expenditure, 0 otherwise, captures firm effort in innovative activities. The use of the R&D indicator is preferred since 64% of firms who report having spent money on research and development activities, either in-house or outsourced, do not disclose these amounts. A continuous variable defined as the natural logarithm of R&D expenditure is used in the sensitivity analysis, but these results should be handled with care.

B. Subsidies

The next crucial survey data used is information on whether the firm has received any subsidies in the last 3 years. The BEEPS question mentions several possible sources of subsidies, namely from the national, regional or local governments and European Union sources. It does not distinguish among them, however, and does not report amounts of subsidies. No details are provided about the purpose of the subsidies. This is why the analysis can only investigate whether receipt (or not) of subsidies is linked with firm innovation while controlling for R&D effort. Subsidy takes a value of 1 if the firm has received any subsidies from any source and 0 if otherwise.

C. Financial strength

BEEPS 2009 collects a host of information regarding firms’ current and past financial situation. For instance, using survey responses, two variables gauge firms’ current access to external finance. CreditLine takes a value of 1 if the firm had a line of credit or a loan from a financial institution and 0 if otherwise. Similarly, Overdraft is coded 1/0 if the firm had an overdraft facility at the time of the interview. Firms are also asked to estimate the proportion of funds from various sources used to finance purchases of fixed assets over fiscal year 2007. BankLoan is coded 1/0 if the firm borrowed from private or state-owned banks to fund purchases of fixed assets. Firms which did not purchase any fixed assets in 2007 were not asked this question. Ayyagari et al. (2011) use a similarly defined variable to show that access to bank financing is positively associated with the extent of innovation undertaken by firms in emerging economies.

Internal finance availability at the time of the interview is gauged by CashHolding, defined 1/0 if firms report having a checking or savings account. This variable is similar to the cash holdings measure advocated by Brown et al. (2012) and avoids the drawbacks associated with the use of cash flow mentioned in Section 2.1.Footnote 12

Overdue is defined 1/0 if the firm has overdue payments by more than 90 days. It is similar in nature to the overdue payments to suppliers indicator proposed by Aghion et al. (2012) as a measure of firm financial constraints. While earlier rounds allowed separation of overdue payments into four categories (utilities, taxes, employees and material input suppliers), the fourth round of BEEPS used here reports information only about overdue payments to utilities or taxes.

Besides measures of actual use of (external and internal) finance, BEEPS reports respondents’ opinions on what are their major obstacles to firm growth and performance. FC is set equal to 1 if firms choose access to finance as their current biggest obstacle and equal to 0 if they choose any of the other 14 possible answers (details in the data appendix). This provides a direct measure of self-reported financial constraints.

D. Controls

The analysis includes several control variables likely to impact on whether a firm undertakes innovative activities. Consistent with the literature, the logarithm of the number of employees (EMP) and its squared term (EMP2) allow for a potential non-linear size effect. Age, calculated as the logarithm of the number of years since the company was formally registered, controls for two possible effects. On the one hand, older firms may have accumulated knowledge and may therefore be more likely to innovate. On the other hand, older firms may have developed routines and may be more rigid and less likely to engage in innovative activities.

The survey includes several questions about market characteristics and the degree of competition in the market. It is generally accepted that foreign competition and exporting status impact firm behaviour. Accordingly, all regressions control for whether the firm engages in export markets (Export) and whether it has majority foreign capital (Foreign). Some models take into account whether the respondents are part of a larger firm (Group).

Firms are asked directly how important domestic competitors, foreign competitors and customers, were in affecting their decisions to develop new products or services and markets. Using the four-ordered responses, three measures (Pres_dcomp, Pres_fcomp, Pres_cust) are coded 1 if the firm answers ‘fairly important’ or ‘very important’ and 0 if the firm answers ‘not at all important’ or ‘slightly important’, regarding the pressure exerted by domestic competitors, foreign competitors and customers, respectively.Footnote 13 Furthermore, City is an ordinal variable taking five values corresponding to the population size of the city where the firm is located (1 = capital city and 5 = town with population less than 50,000).

Additional detailed information is available in the manufacturing firms’ questionnaire. For instance, with reference to year 2007, the survey provides information about the number of competitors (Compet) grouped into four categories: 1 (no competitors), 2 (1 competitor), 3 (2–5 competitors) and 4 (more than 5 competitors). Market takes a value of 1 if the firm’s main product market is local, 2 if it is national and 3 if the firm mainly sells on the international market. There is data on firm capacity utilisation (CU), capital intensity (CapIntens), defined as the net book value of machinery, vehicles and equipment relative to permanent full-time employees in 2007 and whether the firm imported material inputs or supplies (Importinp). A firm’s ability to innovate depends to a large extent on the knowledge base of its employees, which can be measured by formal training provided to its full-time employees (Training).

Industry dummies control for unobserved heterogeneity across industries that may not be captured by other observables. Industry characteristics are important as they are likely to affect firm innovativeness, firm financial strength and reliance on external funding, as well as the likelihood of receiving subsidies. Industries are also important in determining the relevant market in which firms operate.Footnote 14 Industry groups are based on the actual establishment’s (four digits) industry classification. Finally, country dummies capture other country-specific fixed effects.Footnote 15 Appendix Table 12 describes the country and industry composition of our data.

4.2 Summary statistics

Table 1 summarises, by country, the proportions of firms that undertook different innovative activities over the 3 years prior to the survey (panel A). Across countries, the most common innovative activity is upgrading an existing product, followed by the introduction of a new product or service. On average, the proportion of firms that upgraded an existing product or service (73.3%) is roughly three times larger than the percentage of firms that outsourced an activity (25.8%) or discontinued an existing product or service (24.3%). Slightly more than half the firms introduced a new product (54.1%) in the last 3 years. These raw descriptive statistics support the use of NewProduct and Upgrade as the main indicators of firm innovative activities in this study and are consistent with the numbers calculated by Ayyagari et al. (2011) using the 2006 World Bank Enterprise Survey.

Looking at the proportions across countries, Lithuanian and Slovenian firms seem to be the most innovative. In Lithuania, 91.2% of firms have upgraded a product or service and 69.8% of firms introduced a new product or service in recent years, which compares well with the proportions for Slovenia (90.8% upgraded and 74.5% introduced new products). At the other extreme, Uzbek firms are the least innovative across all categories (23% upgraded and 37.4% introduced new products). At the same time, Uzbekistan stands out as the country with the lowest proportion of firms (2.5%) that spent a positive amount on R&D activities in 2007, which is ten times lower than the sample average (24.6%).

Panel B of Table 1 presents additional statistics (mean, standard deviation and number of observations) where responses are grouped according to country EU membership in 2004. The Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia are considered EU member countries. The non-EU countries include Albania, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, FYR Macedonia, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, Moldova, Mongolia, Montenegro, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Tajikistan, Turkey, Ukraine and Uzbekistan.Footnote 16 There are statistically significant differences in firm innovativeness across the two country groups. Not surprisingly and consistent with the idea that firms in less-developed economies engage mainly in imitation, firms in non-EU countries are more likely to upgrade an existing product/service, while the average proportion of firms that introduce a new product/service is higher in EU countries. Nevertheless, the standard deviations for the innovation indicators are large and conceal the fact that firms in some non-EU countries (e.g. Russia and Armenia) are more innovative than firms within some EU countries (e.g. Hungary). The striking difference across the two country groups regards, however, the proportion of firms that report receipt of public subsidies: 16.2% for firms in EU countries relative to 5.7% in non-EU countries, with Croatia (26.6%) and Armenia (0.8%) at the two extremes.

Finally, panel C shows that on average, firms receiving subsidies are more innovative than firms which do not receive any subsidies. The differences are statistically significant for all indicators of firm innovation including engagement in R&D.

Table 2 reports the sample statistics of the variables measuring firm financial strength (panel A). Slightly less than half of the surveyed firms had access to a credit line or loan from a financial institution (47.8%) or to an overdraft facility (45.1%) at the time of the interview. Bank loans were the funding source for about 40% of the firms that purchased fixed assets in 2007. The vast majority of firms have a checking or savings account.Footnote 17 About 7% of firms experience payments overdue by more than 90 days with utilities or taxes. Finally, the self-reported measure of financial constraints suggests that 17% of firms rank access to finance as the major obstacle to their establishment’s operation. Panel B suggests that on average, firms in EU countries are financially stronger than firms in non-EU countries. These differences are statistically significant, with the exception of payments overdue for more than 90 days.

Panel C provides some descriptive statistics for the other controls. While there is large variation in terms of the number of employees (ranging from 1 to 100,000), the vast majority (64.8%) of the sample firms are classified as small (less than 50 employees) and 90.7% of firms are SMEs (less than 250 employees). About a quarter of firms export their goods directly or indirectly, and roughly 7% of firms have majority foreign capital. The average firm age is 16 years but the large standard deviation suggests the sample contains a mixture of very young and old firms. The other controls are self-reported measures of degree of competition in the product market and, for manufacturing firms only, different measures of capital utilisation and productivity. These statistics suggest that domestic agents, customers and competitors alike, put pressure on firms to innovate, while foreign competitors play a much lesser role. On average, firms operate close to three quarters of their full capacity. Nearly 40% of firms provided training to their full-time permanent employees in 2007.

Table 3 presents simple correlation coefficients. The positive correlations between the alternative measures of firm innovation are statistically significant at the 5% level and the strongest relationship is between the two main dependent variables NewProduct and Upgrade (panel A). Better firm financial strength and receipt of subsidies are associated with increased innovation (panel B). The coefficients in panel C suggest that larger and older firms are more innovative. Similarly, innovative firms are likely to export, have foreign capital, belong to a group and provide training to their employees. Finally, according to panel D, more intense competition is associated with increased firm innovation.

5 Empirical results

5.1 Baseline results

The empirical analysis begins by estimating the probability that firm i undertakes an innovative activity. Table 4 reports marginal effects calculated at mean values and robust standard errors clustered at the country level. The baseline model includes non-linear firm size effects and controls for export participation, foreign capital, R&D effort and industry- and country-fixed effects. The results suggest that there is a non-linear relationship between firm size and the likelihood that the firm innovates (introduces new products and services as well as upgrades an existing product or service). Both export participation and presence of foreign capital exert large and significant effects on firm innovative activities. Firm age and being part of a larger firm (Group, a standard control in the R&D subsidy literature) do not appear to significantly affect firm innovative activities in this sample.

The marginal effects suggest that a major determinant of firm innovative activities over the period 2007–2009 is firms’ engagement in R&D activities in 2007. For sensitivity purposes, Table 13 in the Appendix replaces the R&D indicator variable with a continuous measure, the natural logarithm of (1+ R&D expenditure). While the estimates are qualitatively similar irrespective of the R&D measure used, the R&D dummy variable is preferred. The reason is that among the 2920 firms indicating they have engaged in R&D activities, only 1047 report non-negative R&D expenditure amounts while the other 1873 firms do not disclose these amounts. These are coded as missing values for the continuous R&D variable. This explains the lower number of observations in Table 13 relative to Table 4.

Importantly, the estimates suggest a positive and significant relationship between subsidies and firm innovative activities. Subsidies are more strongly correlated with the likelihood of introducing new products or services (columns 1–4) than with the likelihood of upgrading an existing product or service (columns 5–8). This finding continues to hold when the estimation controls for firm financial strength (captured by CreditLine) and is not sensitive to the measure of R&D effort used.

Financial strength variables

All Table 4 specifications capture firm financial strength by CreditLine, an indicator that the respondent has a line of credit or a loan from a financial institution. Table 5 uses alternative measures for firm financial strength. Access to external funding is measured by availability of an overdraft facility (columns 2 and 6) or by the use of bank loans to purchase fixed assets (columns 3 and 7). Internal finance strength is proxied by the existence of a checking or savings account (columns 4 and 8). All these estimates suggest that financial strength relates positively with firm innovation. Irrespective of the measure used, firm financial strength is more strongly correlated with the likelihood of introducing new products/services than with the probability of upgrading existing ones. This finding is consistent with the higher degree of risk and lower collateral value of activities related to introducing new products relative to upgrading existing ones. Importantly, subsidised firms are always more likely to innovate regardless of the firm financial strength measure used. The marginal effects are roughly twice larger for NewProducts than for Upgrade.

Market characteristics

The analysis focuses next on the relationship between firm innovativeness and market characteristics. One can argue that the intensity of competition in the product market is the device that gives firms an incentive to innovate. Besides exporting status and foreign capital, the empirical analysis considers now other measures of product market competition including the number of competitors (Compet), the population size of the city where the firm is located (City = 1/5 with 1 for capital, 5 for towns with less than 50,000 people), whether the firm uses imported inputs (Importinp), the main product market in the previous year (Market) and the importance of various factors affecting firms’ decisions to develop new products and services.

Overall, the results in Table 6 suggest that competition is positively associated with increased innovation. For instance, firms located in larger cities are more likely to upgrade existing products but the association between city size and the likelihood of introducing new products is weaker. The estimates suggest that firms innovate due to pressure from domestic competitors and customers, while pressure from foreign competitors plays no role. This result holds also in the manufacturers sample when allowance is made for the main product market, where firms selling on more competitive markets (national and international) are more likely to introduce new products. A higher number of competitors (columns 4 and 9) and using imported inputs correlate positively with the probability that manufacturers engage in both innovative activities.

Additional checks

Table 7 collects results obtained on the manufacturers sample and control for capacity utilisation, capital intensity and training provided to full-time employees in 2007, respectively. Capacity utilisation appears positively associated with the likelihood of upgrading existing products while capital intensity (the net book value of machinery, vehicles and equipment relative to the number of permanent full-time employees) is positively correlated with the likelihood of introducing new products. There is evidence of a significant positive association between human capital (as measured by formal training provided to firms’ permanent full-time employees) and firm innovation. The marginal effects calculated at the mean are large: 13.5% for introducing new products and 9.4% for upgrading existing ones.

5.2 Subsidy effects for financially constrained firms

Throughout the analysis, it appears that financially stronger firms and firms receiving subsidies are more likely to innovate. This section considers whether the relationship between subsidies and firm innovation varies with financial constraints. The marginal effects in Table 8 are obtained from models in which Subsidies and the respective financial strength variable are interacted with FC and (1-FC). The interactions with FC (=1 if access to finance is the firm’s biggest obstacle) refer to the link between subsidies (respectively, financial strength) and the innovation of financially constrained firms, while the interactions with (1-FC) refer to financially unconstrained firms. All specifications control for industry and country effects and cluster standard errors at country level. Across columns, both subsidies and firm financial strength are more strongly related with the probability of introducing new products for financially constrained firms. The results for Upgrade are weaker. This could be due to the fact that financial constraints are likely to be stronger for the introduction of new products, associated with more severe asymmetric information, than for upgrading existing products.

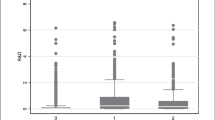

Table 9 collects additional results when the variables reflecting firm financial strength at the time of the interview (credit line use, overdraft facility and cash holding) are interacted with receipt (or not) of public funding in the last 3 years, i.e. with Subsidy and No Subsidy.Footnote 18 This approach, similar to Hyytinen and Toivanen (2005), allows the financial variable to impact firm innovation according to receipt (or not) of subsidies.Footnote 19 Panel A reports the marginal effects obtained on the whole sample for both NewProducts and Upgrade. Looking across columns, the financial strength variable attracts larger marginal effects when interacted with Subsidy for both innovation indicators. This finding implies that subsidies enhance firms’ financial strength which then boosts their innovative activities.

An advantage of the dataset is that it allows cross-country comparisons. Panel B reports results for separate samples according to country EU membership.Footnote 20 All interaction terms attract large and generally significant marginal effects in the new products/services specification for both country groups. The marginal effects for the interactions with Subsidy are larger than those for the interactions with No Subsidy and t test results confirm that, in all cases, the difference is statistically significant. This means that subsidies ameliorate financial constraints affecting firm innovation in all countries, but the marginal effects are largest for the non-EU group. In what regards the upgrading of existing products, the interaction terms appear significant only for firms in non-EU countries. Once again, the marginal effects are significantly larger for the interactions with Subsidy relative to those with No Subsidy. These results are in line with the idea that firm innovation in non-EU countries suffers from more binding financial constraints than that in EU countries. Subsidy receipt is thus particularly important for the innovation of firms in countries with less developed financial markets.

5.3 Self-reported financial constraints

This section uses the self-reported measure of financial constraints FC (coded 1 if firms report access to finance as the major obstacle to their business operations, 0 otherwise) instead of balance sheet data regarding use of (external or internal) funding. Gorodnichenko and Schnitzer (2013) construct two similar financial constraints measures using earlier rounds of BEEPSFootnote 21 and suggest using an instrumental variable approach to address the possibility that innovating firms are more likely to face financial constraints than firms that do not innovate. Ayyagari et al. (2011) use the instrumental variable probit as robustness check.

The IV probit estimator cannot handle discrete or limited endogenous regressors, which is the case of the endogenous variable FC. To deal with the binary nature of the self-reported financial constraints measure, the baseline model including industry and country fixed effects is estimated with the special regressor estimator proposed by Lewbel (2000).Footnote 22 For purposes of comparison, however, the IV probit estimates are reported in Appendix Table 14. The instrument used is Overdue, defined 1/0 if firms report payments overdue by more than 90 days with utilities or taxes.Footnote 23 The first-stage estimates show that overdue payments are highly significant in predicting firm financial constraints. Overdue will be the instrument used in all specifications below. The second-stage results confirm that employing self-reported measures of financial constraints does not alter the innovation-subsidy relation.

The special regressor estimator has a further advantage relative to the maximum likelihood approach, as it allows for heteroskedasticity of unknown form in the model’s error process. The method relies on a particular ‘special regressor’ that is exogenous and appears additively in the model. The special regressor must be continuously distributed, with a large support so that it can take on a wide range of values and, ideally, it should have thick tails. Firm age (demeaned) is used as the special regressor since it is exogenously determined, continuously distributed and as shown previously (Table 3, panel C), likely to be correlated with firm innovativeness.Footnote 24 While this method requires strong restrictions on one variable, the special regressor age, it provides useful robustness checks against alternative estimators.

As in a probit model, the quantities of interest are marginal effects. Table 10 reports marginal effects and bootstrapped standard errors (100 replications) calculated for the two dependent variables NewProduct and Upgrade. Several sensitivity tests of the special regressor model are conducted. Firstly, the estimator allows for two methods of estimation of the density: the standard kernel density (odd columns) and the sorted data density of Lewbel and Schennach (2007) in even columns. Secondly, outliers are removed to improve the mean squared error of the estimator by trading off bias for variance (Dong and Lewbel 2015) at different percentile values. Columns 1–4 winsorise the 2.5% of the data, while in columns 5–8 tail values are set equal to the fifth percentile of the data.

Looking across columns, irrespective of the method of estimation of the density and the percentile used to winsorise the data, the estimates suggest that financially constrained firms are less likely to innovate. Importantly, as in the simple probit estimations, Subsidies are still positively and significantly associated with firm innovation.

Panel B of Table 8 reports marginal effects obtained with the special regressor on separate samples according to EU country membership, for both NewProducts and Upgrade. All specifications control for industry and country effects and the data is winsorised at the 2.5% tails. Winsorisation at 5% produces qualitatively similar results. Both the kernel (columns 1, 2, 5, 6) and the sorted data (columns 3, 4, 7, 8) density estimators are used to check the robustness of results. These estimates suggest that the positive relation between subsidies and firm innovation seem to be mainly driven by firms in non-EU countries. The implicit assumption here, consistent with the summary statistics, is that firms in non-EU member countries are more likely to be financially constrained than their counterparts in an EU country.

5.4 Matching techniques

Given the secondary survey data used in this study, it is difficult to establish a causal relationship between receipt of subsidies and firm innovation. This would entail showing the counterfactual that had the firm not received any subsidies, it would not have been able to innovate. Subsidised firms may have put more effort into innovative activities than non-subsidised firms even in the absence of the subsidies. As common in the literature on the evaluation of R&D subsidies, this section uses a propensity score matching technique to compare the actual outcome of subsidised firms with their potential outcome in case of not receiving a subsidy. Matching techniques aim to construct a sample counterpart for the treated (i.e. subsidised) firms’ outcomes had they not been treated by using an average of the outcomes of similar firms that were not treated. Similarity between firms is based on estimated treatment probabilities, known as propensity scores. A treated firm is matched to the nearest non-treated firm in the control group in terms of propensity scores for the given set of observable characteristics. Under the matching assumption, the only remaining difference between the two groups is the actual treatment effect.

Table 11 reports the matching results.Footnote 25 The columns labelled average treatment effect on the treated (ATET) give the estimated impact of receiving a subsidy on the likelihood of undertaking innovative activities (Newprod and Upgrade) for subsidised firms. As expected, subsidies are more strongly related with the likelihood of introducing new products or services than with the probability of upgrading existing ones, which depends mostly on internal funding.

The rows report the model (variables) used to perform the matching. For instance, in panel A model 1, subsidised firms are matched with non-subsidised firms similar in terms of size, export participation, foreign capital, R&D engagement, financial strength (CreditLine), industry and country. The numbers reported imply that subsidies increase the likelihood of subsidised firms to introduce new products/services (column 1) and to upgrade existing ones (column 4) by 5.9 and 3.3%, respectively. The subsequent models add variables to the matching procedure: belonging to a group (model 2) and age (model 3). The next two models consider market characteristics when matching subsidised and non-subsidised firms: factors exerting pressure on firms to innovate (model 4) and the main product market (model 5). The average treatment effects on the subsidised (relative to the non-subsidised) firms are economically and statistically significant. The smallest coefficients, though significant, are obtained when similarity between treated and untreated firms conditions on the establishment being part of a larger firm for NewProducts and age of the firm for Upgrade, respectively.

Panel B reports average treatment effects on the subsidised firms when the matching procedure is model 3 replacing credit line with alternative financial variables. These results suggest that subsidies generally have a positive significant impact on the innovative activities of subsidised firms irrespective of the variable used to measure firm financial strength.

Finally, panel C of Table 11 presents average treatment effects obtained from separate samples of firms. Matching is performed according to firms’ size (including non-linear term), export participation, foreign capital, R&D input, financial strength, industry and country. In the first two lines, firms are separated according to self-reported financial constraints, while the other sub-samples reflect whether (or not) firms operate in an EU member state. Firm financial strength is captured, alternatively, by the existence of a credit line (rows 3–4), of an overdraft facility (rows 5–6), the use of bank loans to purchase fixed assets (rows 7–8) and cash holdings (rows 9–10). Overall, the estimates in panel C suggest that public subsidies have a larger impact on the innovative activities of financially constrained firms (either self-reported or operating in a non-EU country). Consistent with the results in panels A and B for the whole sample, the average treatment effects are generally larger for the introduction of new products/services relative to the upgrade of existing ones.

Overall, the results obtained with the four estimation approaches suggest a positive relationship between public subsidies and firm innovation as measured by the introduction of new products and services and the upgrade of existing ones. The relationship appears to be stronger in the presence of financial constraints. As a final robustness check, the whole analysis is done when the innovative indicators are replaced with Outsource and Discont (results not reported). While there seem to be positive subsidy effects in the case of outsourcing activities, there is weak evidence supporting a link between public subsidies and firms discontinuing an existing product or service.

6 Conclusions

This paper investigates the relationship between public subsidies and firm innovation in the context of emerging economies. Innovation activities are defined broadly to include the introduction of new products or services and the upgrade of existing ones, which are of particular relevance for these countries. The detailed firm level data collected by the Business Environment and Enterprise Performance Survey (BEEPS) allows construction of alternative indicators of firm financial strength (access to external funding, internal finance and self-reported measures of financial constraints) and measures of market competition for roughly 12,000 firms across 30 countries in Eastern Europe and Central Asia. A range of econometric techniques, including a standard probit model, instrumental variables (probit and special regressor) and treatment effects, provides robustness of results to the choice of estimator. Although there may be considerable variation in the details of how subsidy programs are implemented and other institutional, political and cultural factors may influence the effects of subsidies on innovation, our analysis identifies some robust patterns across countries.

The paper finds a positive correlation between receipt of subsidies and the innovative activities of firms in emerging economies. The positive link appears to be stronger for firms more likely to be financially constrained. Notably, our results are obtained using data covering the period 2007–2009, when many of the countries in our sample were affected by the financial crisis. While firm innovative activities are always likely to be subject to more stringent financing constraints than other firm activities, this is likely to be exacerbated during periods of crisis.Footnote 26 As innovative firms introducing new products, services, processes or business models are more likely to create new markets, achieve rapid growth and help the economy recover (Lee et al. 2015), our findings highlight the importance of public support to firms in these economies.

Our results have clear policy value. The positive link between finance and innovation points towards the importance of financial market development. Policy measures fostering financial market development, in conjunction with the national institutional framework, could help stimulate firm innovation in emerging economies. As financial constraints for innovation prevail even in developed economies, direct public provision via subsidies maintains an important role especially for financially constrained innovative firms. Innovation policies in emerging economies could, however, be gradually designed taking into account the potential additional benefits of using both direct and indirect instruments (loan programmes, guarantees, R&D tax incentives). Finally, our results have indirect implications for industrial policy as well as captured by the positive impact of product market competition and participation in export markets on increased firm innovation.

The cross-sectional nature of the data allows us only to identify a positive static relation between subsidies and firm innovation. Ideally, availability of panel data would help identify whether subsidy policies may have lagged effects on innovation as well. As suggested by Arque-Castells and Mohnen (2015), tailored subsidy policies could both trigger new firms engage in R&D and support existing innovators. Ensuring innovation continuation and persistence over time would make public intervention via subsidies of utmost importance for emerging economies, given the positive link between innovation and long-term economic growth. Clearly, the net effect of lagging behind or catching up with industrialised economies would depend on several other policy instruments in developed and developing countries, which are beyond the scope of this paper.

Notes

While government intervention takes mainly the form of direct grants, several OECD countries offer R&D tax incentives as well. Consequently, a separate strand of research has evaluated the impact of tax credits on R&D. The literature review section mentions this strand briefly as tax incentives are not present in most of our sampled countries and data is not available.

Acemoglu et al. (2006) argue that innovation becomes more important relative to imitation only when the country approaches the world technology frontier.

The Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, the Slovak Republic and Slovenia became EU member countries in 2004. Bulgaria and Romania joined the EU in 2007. As some of the survey questions refer to the previous 3 years, the latter two countries may be included either in the EU or the non-EU group—this is inconsequential for our findings. The non-EU countries include Albania; Bosnia and Herzegovina; Croatia; FYR Macedonia; Kosovo; Montenegro; Serbia; 10 former Soviet Union countries (Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Kazakhstan, Moldova, Russia, Tajikistan, Ukraine and Uzbekistan); Mongolia; and Turkey.

Various sources provide different lists of countries classified as emerging economies. All the countries in our dataset (except Mongolia) were also sampled by Ayyagari et al. (2011). Following their terminology, we refer to these countries as emerging economies. It is important to note, however, that whether this term applies to a particular country may change over time.

Basically, Fazzari et al. (1988) compare the results for the investment-cash flow relationship for several (the q, the neoclassical, and the accelerator) models of investment across firm categories according to their earnings retention. They interpret the larger cash flow sensitivity for firms that retain and invest most of their income relative to that for firms paying high dividends as evidence that financial constraints affect firm investment. Their tests are mainly based on linear estimation of static panel investment models including cash flow and internal liquidity. Their analysis, however, ignores controls for external financing sources and gives little thought to the possibility of cash flow endogeneity.

Kapil et al. (2013) propose the introduction of tax incentives in Poland additional to direct EU state aid.

The survey was first undertaken in 1999–2000, and was followed by subsequent rounds in 2002, 2004–2005 and 2008–2009. Data for the fifth round, 2012–2013, became available in January 2015.

This corresponds to firms classified with ISIC Rev 3.1 codes 15–37, 45, 50–52, 55, 60–64 and 72. Prior to 2008, the survey universe consisted of industry and most service sectors. This corresponded to firms classified with ISIC Rev 3.1 codes 10–14, 15–37, 45, 50–52, 55, 60–64, 70–74, 92.1–92.4 and 93.

Other papers, e.g. Aerts and Schmidt (2008) and Czarnitzki and Lopes-Bento (2013), use information on the firms’ patent stock instead. We cannot follow this approach due to the anonymity of firms in the BEEPS sample which makes it impossible to match in patent data. Moreover, while patent data is accurately measured, it has its drawbacks: it measures inventions rather than innovations; firms often use measures other than patents to protect their innovations; the tendency to patent varies across countries and industries. The analysis will control for industry and country specific patterns by including industry and country fixed effects.

Czarnitzki and Hottenrott (2011a) suggest using the empirical price-cost margin = (sales − labour and material costs + δ R&D expenditure)/sales, where the labour and material cost shares (δ = 0.93) of the R&D expenditure are added back in order to measure internally available funds during the year irrespective of the actual decision on R&D investment. We do not use this indicator due to data restrictions: the large proportion of missing data for R&D expenditure (mentioned above) and the availability of material costs only for manufacturing firms reduces the number of observations for this variable to roughly a quarter of sample size.

Using the 2003 Mannheim Innovation Survey, Cappelli et al. (2014) find that pressure from competitors matter for imitation, while customers and research institutions deliver valuable knowledge for sales with market novelties, and there are no significant spillover effects from suppliers.

Beneito et al. (2015) construct several measures of product substitutability, market size and entry costs in their empirical analysis on the relationship between market competitive pressure and firm innovation.

The country-specific effects include institutional factors such as intellectual property rights, corruption and cultural and property rights. See Krasniqi and Desai (2016) for a detailed country-level analysis of institutional drivers of high-growth firms.

EU membership is defined using 2004 as cutoff. Bulgaria and Romania joined the EU on 1 January 2007. For respondents in these two countries, questions referring to the previous 3 years would include pre-EU periods. Croatia became an EU member on 1 July 2013. These three countries are considered non-EU members. However, as they must have had sufficiently developed financial markets and institutions in order to be allowed entry later on, they are included in the EU group in robustness tests.

BEEPS reports missing values for the Slovak Republic since the translation of the question inaccurately only asked about a savings account, which made the data not being comparable across countries.

The variable BankLoans is not interacted with the indicators of subsidy receipt as the question regarding the use of bank loans to purchase fixed assets refers to year 2007, which means it may precede subsidy receipt.

Hyytinen and Toivanen (2005) interact government funding in a given area with four alternative measures of industry dependence on external finance to show that government funding disproportionately affected the R&D expenditure of Finnish SME firms operating in industries dependent on external finance.

For reasons discussed earlier in note 16, the EU group includes member countries as of 2004. Robustness checks including Bulgaria, Romania and Croatia in the EU group leave results unaltered.

Using earlier rounds of BEEPS, Gorodnichenko and Schnitzer (2013) construct two proxies for self-reported financial constraints: Difficulty of Access to External Finance and Cost of External Finance, each taking four values (0/3) corresponding to whether access to finance and, respectively, cost of external finance are considered ‘no obstacle’, ‘minor’, ‘moderate’ or ‘major obstacle’ for the operation and growth of the business.

The estimation uses the sspecialreg command developed in Stata by Baum (2012).

Aghion et al. (2012) propose a payment incident variable (if the firm fails to pay its trade creditors) as an indicator of firm credit constraints. Similar to this, the instrument used by Gorodnichenko and Schnitzer (2013) is overdue payments to suppliers, which unfortunately is not available in BEEPS 2009.

Dong and Lewbel (2015) use age as the special regressor in their analysis of individual decision to migrate from one US state to another.

Matching is performed using the teffects psmatch command in Stata. The advantage of this command is that it takes into account the fact that propensity scores are estimated rather than known when calculating standard errors. See Abadie and Imbens (2016) for a formal discussion on the application of estimated propensity scores.

Financial constraints likely interact with a number of internal and external factors in setting innovative firms’ ability to react to economic recessions. For instance, in a recent study of Italian small- and medium-sized family firms over the period 2002–2011, Cucculelli and Bettinelli (2016) identify the crucial role played by firms’ organisational learning and adaptive capacity, combined with internal corporate governance and managerial characteristics such as CEO’s origin, tenure and turnover, in firms’ successful responses to economic recession.

References

Abadie, A., & Imbens, G. (2016). Matching on the estimated propensity score. Econometrica, 84(2), 781–807. doi:10.3982/ECTA11293.

Acemoglu, D., Aghion, P., & Zilibotti, F. (2006). Distance to frontier, selection, and economic growth. Journal of the European Economic Association, 4, 37–74. doi:10.1162/jeea.2006.4.1.37.

Aerts, K., & Schmidt, T. (2008). Two for the price of one? Additionality effects of R&D subsidies: a comparison between Flanders and Germany. Research Policy, 37, 806–822. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2008.01.011.

Aghion, P., Askenazy, P., Cette, G., Berman, N., & Eymard, L. (2012). Credit constraints and the cyclicality of R&D investment: evidence from France. Journal of the European Economic Association, 10, 1001–1024. doi:10.1111/j.1542-4774.2012.01093.

Almus, M., & Czarnitzki, D. (2003). The effects of public R&D subsidies on firms’ innovation activities: the case of Eastern Germany. Journal of Business and Economic Statistics, 21, 226–236. doi:10.1198/073500103288618918.

Arque-Castells, P., & Mohnen, P. (2015). Sunk costs, extensive R&D subsidies and permanent inducement effects. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 63, 458–494. doi:10.1111/joie.12078.

Aubakirova, G. (2014). Features of managing innovation activity in the Republic of Kazakhstan. Engineering Economics, 25(2), 160–166. doi:10.5755/j01.ee.25.2.3507.

Ayyagari, M., Demirguc-Kunt, A., & Maksimovic, V. (2011). Firm innovation in emerging markets: the roles of governance and finance. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 46, 1545–1580. doi:10.1017/S0022109011000378.

Baum, C. F. (2012). Sspecialreg: Stata module to estimate binary choice model with discrete endogenous regressor via special regressor method. http://ideas.repec.org/c/boc/bocode/s457546.html.

Beneito, P., Coscollá-Girona, P., Rochina-Barrachina, M. E., & Sanchis, A. (2015). Competitive pressure and innovation at the firm level. The Journal of Industrial Economics, 63, 422–457. doi:10.1111/joie.12079.

Brander, J. A., Du, Q., & Hellmann, T. (2015). The effects of government-sponsored venture capital: international evidence. Review of Finance, 19, 571–618. doi:10.1093/rof/rfu009.

Brown, J. R., & Petersen, B. C. (2009). Why has the investment-cash flow sensitivity declined so sharply? Rising R&D and equity market developments. Journal of Banking and Finance, 33, 971–984. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2008.10.009.

Brown, M., Ongena, S., Popov, A., & Yesin, P. (2011). Who needs credit and who gets credit in Eastern Europe? Economic Policy, 26, 93–130. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0327.2010.00259.x.

Brown, J. R., Martinsson, G., & Petersen, B. C. (2012). Do financing constraints matter for R&D? European Economic Review, 56, 1512–1529. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2012.07.007.

Brzozowski, J., & Cucculelli, M. (2016). Proactive and reactive attitude to crisis: evidence from European firms. Entrepreneurial Business and Economics Review, 4(1), 181–191. doi:10.15678/EBER.2016.040111.

Busom, I., Corchuelo, B., & Martinez-Ros, E. (2014). Tax incentives or subsidies for R&D? Small Business Economics, 43(3), 571–596. doi:10.1007/s11187-014-9569-1.

Busom, I., Corchuelo, B., & Martinez-Ros, E. (2016). Participation inertia in R&D tax incentive and subsidy programs. Small Business Economics. doi:10.1007/s11187-016-9770-5.

Canepa, A., & Stoneman, P. (2008). Financial constraints to innovation in the UK: evidence from CIS2 and CIS3. Oxford Economic Papers, 60, 711–730. doi:10.1093/oep/gpm044.

Cappelli, R., Czarnitzki, D., & Kraft, K. (2014). Sources of spillovers for imitation and innovation. Research Policy, 43, 115–120. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2013.07.016.

Cochrane, J. H. (2005). The risk and return of venture capital. Journal of Financial Economics, 75, 3–52. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2004.03.006.

Colombo, M. G., Grilli, L., & Murtinu, S. (2011). R&D subsidies and the performance of high-tech start-ups. Economics Letters, 112, 97–99. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2011.03.007.

Cowling, M. (2016). You can lead a firm to R&D but can you make it innovate? Small Business Economics, 46, 565–577. doi:10.1007/s11187-016-9704-2.

Cucculelli, M., & Bettinelli, C. (2016). Corporate governance in family firms, learning and reaction to recession: evidence from Italy. Futures, 75, 92–103. doi:10.1016/j.futures.2015.10.011.

Czarnitzki, D., & Hottenrott, H. (2011a). Financial constraints: routine versus cutting-edge R&D investment. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 20, 121–157. doi:10.1111/j.1530-9134.2010.00285.x.

Czarnitzki, D., & Hottenrott, H. (2011b). R&D investment and financing constraints of small and medium-sized firms. Small Business Economics, 36, 65–83. doi:10.1007/s11187-009-9189-3.

Czarnitzki, D., & Lopes-Bento, C. (2013). Value for money? New microeconometric evidence on public R&D grants in Flanders. Research Policy, 42, 76–89. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2012.04.008.

Czarnitzki, D., & Lopes-Bento, C. (2014). Evaluation of public R&D policies: a cross-country comparison. World Review of Science, Technology and Sustainable Development, 9, 254–282. doi:10.1504/WRSTSD.2012.047690.

Czarnitzki, D., Ebersberger, B., & Fier, A. (2007). The relationship between R&D collaboration, subsidies and R&D performance: empirical evidence from Finland and Germany. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 22, 1347–1366. doi:10.1002/jae.992.

Czarnitzki, D., Huergo, E., Köhler, M., Mohnen, P., Pacher, S., Takalo, T., Toivanen, O. (2015). Welfare effects of European R&D support policies. mimeo. SIMPATIC working paper no 31, December 2014. http://simpatic.eu/wp-content/uploads/2015/01/D37n31_counterfactualpolicy.pdf.

Dong, Y., & Lewbel, A. (2015). A simple estimator for binary choice models with endogenous regressors. Econometric Reviews, 34, 82–105. doi:10.1080/07474938.2014.944470.

Erol, T. (2005). Corporate debt and output pricing in developing countries: industry level evidence from Turkey. Journal of Development Economics, 76, 503–520. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2004.01.005.

Fazzari, S. M., Hubbard, R. G., & Petersen, B. C. (1988). Financing constraints and corporate investment. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, 1, 141–195.

Ginevičius, R., Podvezko, V., & Bruzge, Š. (2008). Evaluating the effect of state aid to business by multicriteria methods. Journal of Business Economics and Management, 9(3), 167–180. doi:10.3846/1611-1699.2008.9.167-180.

Girma, S., Görg, H., & Strobl, E. (2007). The effect of government grants on plant level productivity. Economics Letters, 94, 439–444. doi:10.1016/j.econlet.2006.09.003.

Gorodnichenko, Y., & Schnitzer, M. (2013). Financial constraints and innovation: why poor countries don’t catch up. Journal of the European Economic Association, 11, 1115–1152. doi:10.1111/jeea.12033.

Hajivassiliou, V., & Savignac, F. (2016). Financing constraints and a firm’s decision and ability to innovate: Novel approaches to coherency conditions in dynamic LDV models, mimeo. https://econ.lse.ac.uk/staff/vassilis/pub/papers/pdf/financing_constraints_innovation.pdf.

Hall, B. H. (2002). The financing of research and development. Oxford Review of Economic Policy, 18, 35–51. doi:10.1093/oxrep/18.1.35.

Hall, B. H., & Lerner, J. (2010). The financing of R&D and innovation. In B. H. Hall & N. Rosenberg (Eds.), Handbook of the Economics of innovation (pp. 609–639). Amsterdam: Elsevier. doi:10.3386/w15325.

Hanedar, E. Y., Broccardo, E., & Bazzana, F. (2014). Collateral requirements of SMEs: the evidence from less-developed countries. Journal of Banking and Finance, 38, 106–121. doi:10.1016/j.jbankfin.2013.09.019.

Himmelberg, C. P., & Petersen, B. C. (1994). R&D and internal finance: a panel study of small firms in high-tech industries. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 76, 38–51. doi:10.2307/2109824.

Hottenrott, H., & Lopes-Bento, C. (2014). (International) R&D collaboration and SMEs: the effectiveness of targeted public R&D support schemes. Research Policy, 43, 1055–1066. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2014.01.004.

Hottenrott, H., Lopes-Bento, C., & Veugelers, R. (2014). Direct and cross-scheme effects in a research and development subsidy program, DICE Discussion Paper, No. 152. http://www.dice.hhu.de/fileadmin/redaktion/Fakultaeten/Wirtschaftswissenschaftliche_Fakultaet/DICE/Discussion_Paper/152_Hottenrott_Lopes-Bento_Veugelers.pdf.

Hsu, P.-H., Tian, X., & Xu, Y. (2014). Financial development and innovation: cross-country evidence. Journal of Financial Economics, 112, 116–135. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2013.12.002.

Hyytinen, A., & Toivanen, O. (2005). Do financial constraints hold back innovation and growth? Evidence on the role of public policy. Research Policy, 24, 1385–1403. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2005.06.004.

Kapil, N., Piatkowski, M., Radwan, I., & Gutierrez, J. J. (2013). Poland enterprise innovation support review: from catching up to moving ahead. Washington DC: World Bank http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/914151468093563494/Poland-Enterprise-innovation-support-review-from-catching-up-to-moving-ahead Accessed 4 December 2016.

Kaplan, S. N., & Zingales, L. (1997). Do investment-cash flow sensitivities provide useful measures of financing constraints? Quarterly Journal of Economics, 112, 169–215. doi:10.1162/003355397555163.

Kim, W., & Weisbach, M. S. (2008). Motivations for public equity offers: an international perspective. Journal of Financial Economics, 87, 281–307. doi:10.1016/j.jfineco.2006.09.010.

Kobayashi, Y. (2014). Effect of R&D tax credits for SMEs in Japan: a microeconometric analysis focused on liquidity constraints. Small Business Economics, 42, 311–327. doi:10.1007/s11187-013-9477-9.

Krasniqi, B. A., & Desai, S. (2016). Institutional drivers of high-growth firms: country-level evidence from 26 transition economies. Small Business Economics, 47, 1075–1094. doi:10.1007/s11187-016-9736-7.

Lach, S. (2002). Do R&D subsidies stimulate or displace private R&D? Evidence from Israel. Journal of Industrial Economics, 50, 369–390. doi:10.1111/1467-6451.00182.

Lee, N., Sameen, H., & Cowling, M. (2015). Access to finance for innovative SMEs since the financial crisis. Research Policy, 44, 370–380. doi:10.1016/j.respol.2014.09.008.

Lewbel, A. (2000). Semiparametric qualitative response model estimation with unknown heteroskedasticity or instrumental variables. Journal of Econometrics, 97, 145–177. doi:10.1016/S0304-4076(00)00015-4.

Lewbel, A., & Schennach, S. (2007). A simple ordered data estimator for inverse density weighted functions. Journal of Econometrics, 186, 189–211. doi:10.1080/07474938.2014.944470.

Mulkay, B., Hall, B. H., & Mairesse, J. (2001). Firm level investment and R&D in France and the United States: a comparison. In D. Bundesbank (Ed.), Investing today for the world of tomorrow (pp. 229–273). Berlin: Springer Verlag.