Abstract

Prospect theory is the most influential descriptive alternative to the orthodox model of rational choice under risk and uncertainty, in terms of empirical analyses of some of its principal parameters and as a consideration in behavioural public policy. Yet the most distinctive implication of the theory—a fourfold predicted pattern of risk attitudes called the reflection effect—has been infrequently studied and with mixed results over money outcomes, and has never been completely tested over health outcomes. This article reports tests of reflection over money and health outcomes defined by life years gained from treatment. With open valuation exercises, the results suggest qualified support for the reflection effect over money outcomes and strong support over health outcomes. However, in pairwise choice questions, reflection was substantially ameliorated over life years, remaining significant only for treatments that offered short additional durations of life.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Neoclassical economics and the standard theory of rational choice under conditions of risk and uncertainty (i.e. von Neumann-Morgenstern expected utility theory)—hereon defined as orthodox theory—postulate that people should adopt a consistent risk attitude across all decisions that offer outcomes that do not occur with certainty. More specifically, it is typically assumed that marginal utility diminishes with increasing money outcomes, as indicated by curve aa in Fig. 1, and thus that an individual will be consistently risk averse—although in several articles Matthew Rabin argues that orthodox theory does not permit risk aversion over anything other than very large outcomes, and that near universal risk neutrality is the more accurate assumption (e.g. see Rabin 2000). However, at least some of the founding fathers of neoclassical economic theory acknowledged that actual choice behaviours regularly reveal inconsistent individual risk attitudes across different circumstances. For instance, Alfred Marshall (1920), in relation to occupational choice, wrote that people will tend to be risk averse in the face of modest outcomes, but will be risk seeking when a few very large outcomes are offered, and we know from common observation that many individuals both gamble and insure.

In 1952, Harry Markowitz presented a more formal challenge to whether the assumption of a consistent risk attitude holds up in descriptive choice. Markowitz posed a series of questions that involved choices between a 10% chance of money gains or losses of $1 to $10,000,000 and the expected values of those lotteries. With these questions, Markowitz discovered that his acquaintances were typically risk averse when faced with a 10% chance of large gains and small losses, and risk seeking when faced with a 10% chance of small gains and large losses. He attributed all of these attitudes to the size of the outcome and to whether the outcomes were perceived as gains or losses—i.e. risk aversion over large gains and small losses and risk seeking over small gains and large losses—with the point dividing gains and losses assumed to be present or customary wealth. The shape of Markowitz’s utility curve is depicted as bb in Fig. 1; intimating loss aversion—i.e. the tendency to feel the pain of a loss more acutely than the pleasure of an equal sized gain—Markowitz suggested that the curve falls faster to the left than it rises to the right of the origin.

A generation later, Kahneman and Tversky (1979; 1992), in their work on prospect theory, similarly postulated that utility—or rather, in their words, value—is reference dependent in that it is defined by gains and losses around a reference point, but more so than Markowitz, they specified an empirically supported value curve that is much steeper for losses than for gains, strongly emphasising loss aversion. However, unlike Markowitz’s utility curve, which has concave and convex regions within both the positive and negative domains, Kahneman and Tversky’s value function is entirely concave for gains and convex for losses, giving an S-shaped curve. A typical prospect theory value curve is depicted as cc in Fig. 1.

The curve cc implies declining marginal sensitivity to both mounting gains and mounting losses, and hence risk aversion and risk seeking in the domains of gains and losses, respectively. Therefore, unlike orthodox utility theory but in common with the Markowitz model, prospect theory, by allowing people to take risks, is incompatible with the notion that certainty is always desirable. However, prospect theory introduced a further complication that Markowitz avoided, by also positing that people will overweight small probabilities and underweight large probabilities. The underweighting of large probabilities reinforces the risk attitude predictions inferred from the value function, but the overweighting of small probabilities may reverse the risk attitudes in the domains of gains and losses, such that individuals will now be risk seeking in the former and risk averse in the latter. Thus, probability weighting predicts gambling and insurance behaviours in small probability scenarios. Due to the combined effects of the value and probability weighting functions, Tversky and Kahneman (1992, p.306) note that the “most distinctive implication of prospect theory is the fourfold pattern of risk attitudes.” These risk attitudes are summarised in Table 1, for which Tversky and Kahneman, in a non-incentivised study using simple money lotteries, provided empirical support.

The top left quadrant in Table 1 describes the prospect theory risk attitude prediction when a person is faced with a large probability of a gain—for example, a 99% chance of winning £1000. If an individual is offered a choice between this risky option and the certainty of its expected value of £990, prospect theory predicts that the individual places a high weight on the certainty and will demonstrate risk aversion. The bottom left quadrant describes the predicted risk attitude when faced with a small probability of a gain, such as a 1% chance of £1000. Here, the prediction is that since the individual will overweight the chance of winning, he or she would prefer the gamble over its expected value of £10 and will therefore be risk seeking. The top and bottom right quadrants can be read similarly, and show that prospect theory predicts opposing risk attitudes for losses as compared to gains for both large and small probability scenarios. This fourfold pattern of predicted risk attitudes is known as prospect theory’s reflection effect.

2 Evidence of the reflection effect

Prospect theory has received a lot of attention over the past 25 years, both in terms of the scientific modifications that it makes to standard rational choice theory and in relation to its possible real-world policy implications (e.g. see Kahneman 2011; Oliver 2017; Thaler 2015). Controlled testing of the full reflection effect is relatively scarce, although to supplement this evidence, there is some partial testing of the reflection effect that focuses on the value function of prospect theory using money outcomes.

For example, Schoemaker (1990), using mid-range probabilities, found that his respondents tended towards risk aversion over gains and slight risk seeking over losses in a within-respondent design. Moreover, he observed that the results held for both hypothetical and incentivised choices. Similarly, Laury and Holt (2005) reported risk aversion over gains and risk seeking over losses for low hypothetical outcomes, although the modal pattern switched to risk aversion over gains and losses for high hypothetical outcomes and in circumstances where money could be won. Abdellaoui et al. (2007), using binary choice questions, observed substantial risk aversion over gains and risk seeking over losses at the individual level and, in particular, the aggregate level. Booij et al. (2010), using hypothetical questions, reported mild risk aversion over gains and mild risk seeking over losses, a result that was replicated in a study by Abdellaoui et al. (2013) that used financial professionals as respondents. Baucells and Villasis (2010) revisited the individual level results reported in Schoemaker (1990), Laury and Holt (2005) and Abdellaoui (2000; 2007) for choices that used mid-level probabilities and found that, overall, 47% of respondents demonstrated risk aversion for gains and risk seeking for losses. Baucells and Villasis argued that this does not provide overwhelming support for the reflection effect, and in their own original study they likewise found that just below 50% of their respondents were risk averse over gains and risk seeking over losses.

The evidence on twofold reflection—risk aversion for gains and risk seeking for losses—over money outcomes is therefore a little mixed; the evidence on the full fourfold prospect theory predicted pattern of risk attitudes is even more so. Kahneman and Tversky (1979) provided between-respondent support for the full reflection effect in hypothetical choices, but Hershey and Schoemaker (1980) observed statistically significant consistency with the effect in only 7 of 25 gamble pairs. Moreover, neither Cohen et al. (1987) in an incentivised within-respondent design nor Wehrung (1989) in a non-incentivised within-respondent design observed a pervasive prospect theory reflection effect. Likewise, Harbaugh et al. (2002), using real, simple lotteries, found that respondents did not answer consistently with the fourfold pattern, a result replicated by Harbaugh et al. (2009) when eliciting incentivised responses in pairwise choice, but not when using pricing tasks,Footnote 1 where a strong predicted fourfold risk preference pattern was observed. Similarly, using real incentives, both di Mauro and Maffioletti (2004) and Brooks et al. (2014) confirmed the prospect theory fourfold pattern of risk preferences.

Moreover, in a recent article, Bouchouicha and Vieider (2017) reported results from an incentivised study over gains only and from a non-incentivised study over gains and losses. In order to elicit the certainty equivalent of each money gamble in their studies they presented their respondents with a series of pairwise choices between the gamble in question and a number of sure amounts. The gambles were varied in probabilities and outcome magnitudes. Bouchouicha and Vieider observed that for each outcome level, risk aversion increased with the probabilities over gains in both studies, and risk seeking increased with the probabilities over losses in the non-incentivised study. Taken together, these results are consistent with prospect theory’s fourfold reflection effect.

Thus far, though, the money outcome literature does not allow a clear-cut conclusion to be reached regarding the validity of the prospect theory reflection effect, which sits a little uncomfortably, given the attention that the theory has received in the academic and policy discourses. Moreover, prospect theory has attracted interest not just in policy areas that are concerned principally with money outcomes. Health-related preference elicitation instruments are based on the assumption that people are economically rational, in the sense implied by the orthodox theory of choice under risk and uncertainty, despite evidence to the contrary, and prospect theory has occasionally been drawn into these considerations. Loss aversion is likely to be at least a partial explanation for discrepancies observed between answers to willingness to pay and willingness to accept exercises (e.g. Kahneman et al. 1990), and between different versions of the time trade-off method (e.g. Attema and Brouwer 2008; Oliver and Wolff 2014), for instance. Also, Oliver (2003), inspired by work from Bleichrodt et al. (2001), reported that the internal consistency of the standard gamble, with outcomes defined by longevity, could be improved by adjusting the instrument with some of the modifications that prospect theory makes to standard rational choice theory (see also, van Osch et al. 2004, 2006), and Abellan-Perpiñan et al. (2009) observed that compared to evaluations based on expected utility theory, those based on prospect theory are more consistent with respondents’ direct choices and rankings of different health profiles. Moreover, if we move beyond the specific domain of health outcomes measurements to a focus on incentivising healthier behaviours and developing behavioural economic-informed policy frameworks, for example, we can discover that considerations of aspects of prospect theory have been increasingly evident in the broader health policy debate over recent years (e.g. see Behavioural Insights Team 2010; Oliver 2017). Yet over health outcomes, although there is incidental evidence that people tend to be risk averse over gains and risk seeking over losses in some of the classic studies on framing (e.g. McNeil et al. 1982), and although there has been some limited testing over mid-range probabilities of twofold reflection—e.g. Attema et al. (2013, 2016) observed risk aversion over both gains and losses for life years—there has not been any direct testing of the fourfold reflection effect at all.

This article aims to address this gap in the literature to some extent, by testing for the fourfold reflection effect—the most distinctive implication of the most influential alternative to the orthodox theory of rational choice under risk and uncertainty—in hypothetical health-related scenarios. However, to later compare the extent of the reflection effect between the importantly different contexts of health and financial outcomes, two original studies of the reflection effect over money outcomes will first be reported. The first of these studies on financial outcomes, which builds on previous work by Guthrie (2003), uses a single outcome magnitude of £20,000 and is restricted to tests with only high and low probabilities; in order to test the generalisability of the reflection effect, the second study extends the tests to also include the very large outcome magnitude of £1million and the smaller outcome magnitude of £100, as well as the intermediate outcome magnitude of £10,000, and uses the full range of the probability distribution.

Although necessarily abstract, an attempt is made to lend an element of realism to all of the tests reported below, by taking the questions beyond the presentation of simple abstract lotteries that is standard practice in the existing literature. The risk attitude predictions of orthodox rational choice theory and prospect theory for gains and losses at the ends of the probability distribution are summarised in Table 2. Since the Markowitz model has also attracted some attention in the recent literature (e.g. Bouchouicha and Vieider 2017; Levy and Levy 2002; Scholten and Read 2014), its risk attitude predictions for small to sizable but not huge outcomes are also presented in the table, and will be referred to below.

3 Testing reflection with litigation questions

The orthodox model of rational choice under risk and uncertainty is typically assumed in the economic theory of suit and settlement, with litigants posited as rational actors who make risk neutral or risk averse choices to maximise their outcomes (Guthrie 2003). However, since plaintiffs and defendants operate in the domains of gains and losses, respectively, Guthrie hypothesised that prospect theory will better describe their choices. Where plaintiffs have a low probability of winning, he posited that they will retain the hope that the court will find in their favour, and will consequently be risk seeking. Defendants, on the other hand, will be unwilling to risk a larger loss and will therefore be risk averse. The settlement will favour plaintiffs in these circumstances. Where there is a high probability that the plaintiff will win, Guthrie suggested that the risk attitudes of the two parties will reverse, favouring the defendants.

To illustrate, Guthrie presented law students with hypothetical low probability litigation questions, and asked half of his respondents to assume the role of plaintiff and the other half the role of defendant. Plaintiffs were told that they had to choose between a $50 payment settlement or face a 1% chance of winning $5000 at trial; defendants had to choose between paying $50 or face a 1% chance of having to pay $5000 at trial. Under orthodox rational choice theory, risk aversion—and thus a tendency to settle—is expected from both plaintiffs and defendants. Guthrie reported that 84% of the defendants but only 38% of the plaintiffs preferred to settle, offering some support for prospect theory.

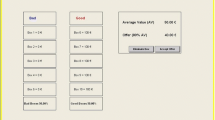

In order to test the full fourfold pattern of risk attitudes, Guthrie’s study is extended here to consider high as well as low probabilities that the plaintiff will win if the case relies on the court. The respondents were 60 postgraduate students, 38 of whom were female. Forty-nine were age 18–30 years, eight were 31–45 years, two were 46–60 years and one was older than 60 years. Forty-eight had studied economics and 30 stated that they like taking risks. Each respondent attended a face-to-face interview that lasted 30–45 minutes, where they answered two sets of four questions. Given the relatively small sample size, a within-respondent design was used. It may be contended that with a within-respondent design there is a danger that respondents will adopt a convenient rule of either gambling or not gambling across all questions, which does not reflect their underlying preferences but which helps them to get through what may for many be a boring task. If so, we might see artificially high consistencies in individual risk attitudes. The counterargument is that one can conclude that any observed systematic inconsistency with the orthodox theory of rational choice is likely to be particularly robust if a within-respondent design is used (Hershey and Schoemaker 1980). Within each set of questions, the question order was randomised across the respondents. The questions in one of the sets are replicated in Fig. 2.

Questions 1 and 3 in the figure asked the respondents to assume that they are plaintiffs in civil law suits where they were respectively facing high and low probabilities that the court would find in their favour.Footnote 2 A 90% chance of success was chosen for the high probability scenario because this was considered high enough for probability transformation to apply, and yet low enough so that respondents would not round up the chance to certainty. Following similar reasoning, a 10% chance of success was chosen for the low probability scenario, although in this question the intention was of course to discourage the respondents from rounding the chance down to 0%. The outcome of the litigation was set at a maximum/minimum of ± £20,000, substantial and imaginable but not life-changing amounts for postgraduate students. The respondents were told that they should not worry about legal fees, which would be covered extraneously whether they won or lost. Questions 2 and 4 in the figure required the respondents to assume the position of the opposing defendants.

In common with Schoemaker (1990) and Harbaugh et al. (2009), the Becker-DeGroot-Marschak (BDM) method was used to elicit the respondents’ answers (Becker et al. 1964). For example, to approximate their certainty equivalents for the risky option of going to trial in question 1, the respondents were prompted to state the minimum amount on which they would settle, say, £x. Once they had decided upon £x, a number between £0–20,000 was generated by a random device. If the random number was equal to or greater than £x, the respondent would settle. If the random number was less than £x, the respondent would be required to go to trial. The BDM method was used to remove, at least in theory, the incentives for respondents to overstate or understate the amounts that they would require/offer when placed in the position of a plaintiff or defendant, respectively.

The literature contests whether real financial rewards can affect the results of laboratory studies. Beattie and Loomes (1997) and Bardsley et al. (2010) report that financial incentives are often not important. Camerer and Hogarth (1999) find that the effect of financial incentives varies across decision tasks, and Hertwig and Ortmann (2001) point out that such incentives can sometimes have an influence. Financial incentives were included in this litigation study in that the money the respondents received for their participation was consequent on the answers that they gave. The outcomes to the plaintiff questions were divided by 10,000 to determine the actual money rewards for each question, but the respondents were not informed of this until they had answered all of the questions.Footnote 3

In one of the sets of four questions, the respondents were asked to assume that they have zero money holdings and that they should approach each question as if this were the case. At the top right hand corner of each question, £0 was typed (in bold) and the respondents were informed at the beginning of the experiment that this was to remind them that they had zero money holdings as they answered the questions. In the other set of four questions, the same respondents were asked to assume that they have money holdings of £100,000 as they addressed each question, and £100,000 was typed (in bold) at the top right hand corner of each question. In all other respects, the questions and the way in which they were administered were identical across the two sets. Half of the respondents answered the questions assuming zero money holdings first, and the other half answered the questions assuming £100,000 money holdings first. The reason for the two different levels of customary wealth was to test whether a manipulation of this factor affected the results. As detailed below, it did not notably, which lends some support to the argument that, over money outcomes, customary wealth is widely accepted as the reference point.

Table 3 summarises the results, first for the questions where the respondents were asked to assume zero money holdings and then money holdings of £100,000. Only those respondents who demonstrated strict risk aversion or strict risk seeking across both questions in each of the four tests are included in the analysis. For example, the first row of Table 3 indicates that 38 of the 60 respondents demonstrated either risk aversion or risk seeking when faced with a 90% chance of winning £20,000, and a 90% chance of losing £20,000. Thus, 22 respondents demonstrated risk neutrality in at least one of these two questions. Whenever respondents demonstrated risk neutrality in any particular question it is difficult to observe the extent to which they concur (or not) with the reflection effect except where respondents are universally risk neutral, which occurred only once.

In the table, SS denotes risk seeking in the domains of both gains and losses, SA denotes risk seeking over gains but risk aversion over losses, AS denotes risk aversion over gains but risk seeking over losses, and AA denotes risk aversion over both gains and losses. The first row in the table demonstrates the extent to which the respondents reversed their risk attitudes when faced with a 90% chance of gaining versus losing £20,000, when their money holdings were zero. Thus, 11% of the respondents were risk seeking in the domains of both gains and losses when faced with high probabilities, a pattern unpredicted by any of the theories considered in this article but one that does at least suggest stable risk attitudes, in common with the orthodox model. Risk seeking over gains and risk aversion over losses here is predicted by the Markowitz model, but is demonstrated by only 3% of the respondents, the same percentage who responded consistently with the orthodox model. The dominant pattern—risk aversion for gains and risk seeking for losses—is that predicted by prospect theory. The extent to which this particular pattern of reflection is systematic—i.e. the extent to which AS patterns outnumber SA patterns—is statistically significant at 0.1%.

All of the other rows in the table can be read similarly. Prospect theory and the Markowitz model predict the same pattern of reflection—SA—for the low probability gambles in these tests, and as with pattern AS for the high probability gambles, although slightly less marked, this is the systematic, statistically significant pattern observed at less than 1% significance. Taking all of the questions together, in terms of the fourfold pattern of risk attitudes over high and low probabilities of gains and losses, there is therefore strong support for the prospect theory reflection effect in these results.Footnote 4,Footnote 5 However, the study is small, and, as noted at the end of Section 2, uses only two probabilities and a single outcome magnitude. A second study was undertaken to observe whether these conclusions held across a range of probabilities attached to varying outcomes.

4 Testing reflection with investment questions

Sixty postgraduates and university research and administrative staff participated in the second test of prospect theory’s fourfold pattern of risk attitudes, none of whom had answered the litigation questions. Forty-five of the respondents were female. Forty-four were age 18–30 years, 13 were 31–45 years, one was 46–60 years and two were older than 60 years. Forty-four had studied economics, and 32 stated that they generally like taking risks. Each respondent attended a face-to-face interview that lasted between 45 and 75 minutes, during which they were required to answer the 30 questions reported here. The questions were described as quasi-realistic investment decisions, and their order was randomised across the respondents in a within-respondent design. Two of the questions are replicated in Fig. 3.

The first question in the figure involves a large chance of a sizeable gain, and the second question presents the same chance of an equivalently sized loss. The BDM method was again used to elicit the respondents’ near certainty equivalents for the investments. The respondents were faced with investments that offered 90%, 70%, 50%, 30% and 10% chances of gaining and losing £1million, £10,000 and £100. Before answering the questions, the respondents were told that their answers would determine their winnings. After completing the questions, the respondents were informed that payments would be normalised so that a maximum of £1 could be earned from each question. The results are summarised in Table 4, which can be read in a similar manner as Table 3. Again, any respondent who demonstrated risk neutrality in a question pair is excluded.

As in the litigation study, the risk preference pattern AS dominates all cases of reflection in the high probability gambles, which is particularly marked in the investment questions for the large outcomes of $1million. For such large outcomes, the Markowitz model also predicts AS patterns across all probabilities, but predicts SA patterns for moderate and small outcomes. Since AS is the modal pattern across all outcome sizes when high probabilities are used, the results in this respect point towards prospect theory reflection.

However, there is not strong support for the prospect theory prediction of SA being the systematic pattern of reflection over small probability outcomes, except for the relatively small outcome magnitude of $100. Although, in line with prospect theory, the overall trend across all outcome sizes is generally one of declining AS patterns and increasing SA patterns as probability diminishes, for moderate and large outcomes the differences in the number of respondents demonstrating these patterns suggest that for low probabilities, reflection cannot be attributed to anything more than random noise.

The orthodox prediction of universal risk aversion is rarely observed in these results. Where consistency in risk attitude is observed, it is in most cases more likely when respondents showed themselves to be risk seeking over both gains and losses. This pattern becomes more evident as outcome size declines, and can be attributed to more respondents demonstrating SS patterns at the expense of AS patterns. In other words, with smaller outcomes more respondents were willing to throw caution to the wind in the gains domain, which, in and of itself, is a phenomenon that was predicted by Markowitz and was also observed by Bouchouicha and Vieider (2017).Footnote 6 Although Markowitz overlooked the possible effect of subjective probability on observations of reflection, which prevented him from seeing the full descriptive picture of risk-related decision making, his recognition that different magnitudes of outcome can flip risk attitudes in the domain of gains was somewhat perceptive.Footnote 7,Footnote 8

Overall, the results from the investment questions, like those previously reported in the literature on the reflection effect, are a little mixed, but taking the litigation and investment studies together there is guarded support for the fourfold prospect theory reflection effect in these tests, particularly over relatively smaller outcomes.Footnote 9 This is for money outcomes; as noted earlier, fourfold reflection has yet to be studied over a different outcome domain of public policy—that of health outcomes—which seems remiss given that prospect theory has attracted substantial attention in the recent health policy literature.

5 Testing reflection with health-related questions

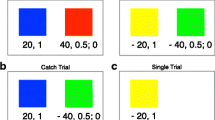

Sixty postgraduates and university research and administrative staff, who had not participated in the first two studies reported above, answered 30 hypothetical health care-related questions. Forty-five of the respondents were female. Forty-seven were age 18–30 years and 13 were 31–45 years. Forty-four had studied economics, and 32 stated that they generally like taking risks. The respondents were of a mix of different nationalities. Each respondent once again attended a face-to-face interview to answer the questions. The order of the questions was randomised across the respondents, and two of the questions are replicated in Fig. 4.

Question 1 in Fig. 4 was designed with the intention that the respondents would believe that they are being offered a large chance of a small gain, in terms of additional months of life that they could live, and were prompted for their approximate certainty equivalent of the risky treatment option. They were told that they should assume that, for all questions, additional longevity would be experienced in full health, so as to simplify an already complicated task. Moreover, months rather than years of life were chosen throughout, to discourage the respondents from rounding their answers to a nearest year, and thus in the hope that this would cause them to fine-tune their answers. Question 2 is the loss-framed analogue of Question 1. The respondents were prompted to push themselves down to the minimum number of months that they would require, and the maximum number of months that they would forgo, in the gain and loss framed questions, respectively, so as to approximate their certainty equivalents as closely as possible. The respondents were faced with questions that involved health care treatments offering 90%, 70%, 50%, 30% and 10% chances of intended perceived gains and losses of 36 months, 180 months and 480 months of life.Footnote 10 The respondents were paid a flat fee of £10 for their participation. The results are summarised in Table 5.Footnote 11

The results strongly support the prospect theory reflection effect. Irrespective of outcome size, the risk preference patterns predicted by prospect theory are the modal observation in almost all cases; they are systematically and statistically significantly in the direction of risk aversion over gains and risk seeking over losses for high probability gambles, and risk seeking over gains and risk aversion over losses for low probability gambles.Footnote 12 On the basis of the results reported in this article, therefore, the prospect theory fourfold pattern of reflection has the potential to be more pervasive over health outcomes defined by longevity than those defined by money when using open valuation tasks, perhaps because considerations pertaining to health are associated with stronger emotions, and thus provoke to a greater extent the feelings of hope and fear, referred to in Table 1. If this result were generalisable, the tendency for patients—or their doctors—to accept risk when faced with losses may be particularly worrisome.Footnote 13

As noted in the introduction, in one of the relatively few tests of the fourfold reflection effect over money outcomes, Harbaugh et al. (2009) reported that while they observed the full effect in valuation tasks of the type used throughout this article, the effect was eliminated entirely in pairwise choice tasks, where respondents were asked to choose explicitly between gambles and their expected values.Footnote 14 Some of those who have tested the twofold pattern of reflection preferred to use pairwise choice tasks as this has been observed to produce fewer inconsistencies than eliciting indifference values (e.g. see Abdellaoui et al. 2007; Booij et al. 2010; Luce 2000); indeed, when using pairwise choices to elicit certainty equivalents over life years, Attema et al. (2013) observed risk aversion over both gains and losses. Given this, the fourfold effect was here also tested with pairwise choices.

The respondents were the same as those summarised above. They answered 30 randomised pairwise choice questions that mirrored the valuation questions, and were paid a further £10 for their participation. The valuation questions and the pairwise choice questions took place a few weeks apart; half of the respondents answered the pairwise choice questions first, and the other half first answered the valuation questions. The pairwise choice questions that correspond to those given in Fig. 4 are reported in Fig. 5, and the results of the study are summarised in Table 6

.

From Table 6, it can readily be seen that compared to the valuation tasks, evidence for the prospect theory fourfold pattern of risk preferences, although not entirely absent, has been substantially diminished in pairwise choice. The pattern remains prominent only for the smallest longevity outcome of 36 months,Footnote 15 suggesting that the affective responses that may cause the reflection effect are perhaps most provoked when people are trying to secure a little additional life. Moreover, this finding has parallels with the study of investment decisions, where it was found that the full fourfold pattern is most evident over small money outcomes.Footnote 16

The other notable finding in these results is the increase in the number of respondents who demonstrated universal risk aversion over gains and losses. Part of the reason for this may have been that some respondents, whose answers suggested risk neutrality in the valuation tasks, were forced into making a choice. Nonetheless, with the exception of the highest and lowest probabilities associated with 36 months of life and the lowest probability associated with 480 months of life, AA is the modal pattern throughout Table 6, a risk preference pattern that was rarely observed in the studies reported earlier. Thus, at least on the basis of this study, pairwise choice over health outcomes defined by longevity is more likely than open valuation to secure risk attitudes that are consistent with the predictions of the orthodox model of rational choice.

6 Discussion and conclusion

Prospect theory is the most influential descriptive alternative to the orthodox theory of rational choice under risk and uncertainty, and its principal postulates are important in the growing field of behavioural public policy. Nonetheless, existing evidence of the most distinctive implication of prospect theory—the full fourfold pattern of risk attitudes known as the reflection effect—is quite scarce and mixed. This article represents an attempt to contribute to this evidence base, over money outcomes and, for the first time, over health outcomes defined by longevity, through the use of abstract but quasi-realistic decision contexts. With valuation questions, the results suggest qualified support for the reflection effect over money outcomes and strong support over the health outcomes used. Prospect theory generally outperformed both the orthodox theory of rational choice and the Markowitz model in the valuation exercises. In line with Harbaugh et al.’s (2009) money outcome results, however, in a within-respondent test of the effect of valuation versus pairwise choice between risky treatments defined by longevity and their expected values, the pairwise choice tasks were found to substantially reduce observations of the reflection effect over life years, with the effect remaining significant only for treatments that offered short additional durations of life and with the orthodox model performing much better than it had in the valuation tasks.Footnote 17,Footnote 18

There were two big shifts in risk preference patterns that explain the differences observed between the valuation and pairwise choice tasks. The first of these was that in the pairwise choice tasks the respondents were more likely to be risk averse when faced with low probability gambles over gains. This can perhaps be explained by an anchoring process distorting respondents’ preferences in the valuation tasks. In the classic preference reversal literature, for which there is evidence over money and health, people tend to choose lotteries with a large probability of a modest outcome over those with a modest probability of a large outcome but value the latter lotteries higher (e.g. Oliver 2006, 2013; Seidl 2002). The most respected explanation for this phenomenon is that respondents use different heuristics across preference elicitation modes. That is, choice tasks might be more likely to focus attention on all that the lottery offers, while valuation tasks may tend to focus attention on the outcomes. That people may focus on the outcomes in the valuation tasks is known as scale compatibility. That is, respondents may be drawn to the money outcomes when asked for money valuations, or longevity when asked to give a life year certainty equivalent for a risky treatment. Moreover, respondents may anchor on the lottery’s best outcome in a valuation task, and fail to adjust the overall value of the lottery downwards sufficiently to take account of its other attributes (Bateman et al. 2007). If people overvalued the health care treatments that offered low probability gains in the valuation tasks reported in this article, this would explain why they appeared to be relatively more risk averse in the pairwise choice questions.

The other substantial movement in the risk preference patterns was that in the pairwise choice tasks the respondents were more likely to be risk averse when faced with gambles over losses, irrespective of probability size. An explanation for this finding is that in the valuation questions, the respondents were asked for the number of months they would be willing to forgo in order to avoid the risky treatment, which might have triggered a heavy dose of loss aversion. If so, and if the pairwise choice questions led to a more considered view of all that the question entails, then this would explain why the pairwise choice tasks tempered the respondents’ answers so that they were more in line with the predictions of the orthodox theory of rational choice.

Possibly the most worrying implication of the results of the valuation questions is that most people, much of the time and in relation to both money and health-related outcomes, appear to be risk seeking in the face of losses, particularly moderate to large probability losses, as prospect theory predicts. If people continually accept risk when faced with losses, they are likely to find themselves in ever deeper trouble. There is real world evidence, at least in relation to money, of this phenomenon; Fiegenbaum and Thomas (1988), for example, found that firms are risk seeking when they are suffering losses, and Wehrung (1989) reported that oil executives are substantially more risk seeking than risk averse when faced with pure losses. Moreover, if we take as given the argument that valuation questions can systematically distort preferences, then there is an argument that methods, used in health care and elsewhere, that rely on such processes, such as open willingness to pay exercises, ought to be used with caution (see also Kahneman and Sugden 2005). However, this is not to conclude that direct choice-based methods offer a panacea; for instance, it is well known that people’s perception of the benefit that any particular good offers them will often be influenced by the available alternatives (e.g. Parducci and Weddell 1986), suggesting that in elicitation exercises, whether value or choice-based, preferences are often anything but fixed and stable.

That said, if the results presented in this article for health-related outcomes and those reported by Harbaugh et al. (2009) over money outcomes were ultimately to prove generalisable, then for pairwise choice tasks prospect theory might have insubstantial predictive power in relation to risk attitudes, at least over moderate to large outcomes. Orthodox rational choice theory may then offer reasonable predictions, whereas open valuation tasks might generally provoke responses that are much more consistent with the predictions of prospect theory. This would leave us open to the possibility that different ways of eliciting preferences in real world scenarios, and different magnitudes of outcomes, may generate responses that are predominantly consistent with different models of choice. These are issues that require further investigation.

Notes

A pairwise or binary choice task will, for instance, offer a respondent a direct choice between a lottery and its expected value (e.g. would you choose a 50% chance of £10 or £5 for sure). A pricing task will elicit the respondent’s certainty equivalent (or approximate certainty equivalent) of the lottery through open valuation (e.g. what is the maximum amount of money you would pay for a 50% chance of £10). A sequence of pairwise choice tasks can also be used to elicit a respondent’s certainty equivalent.

In this and all of the other studies reported in this article, the decision tasks used were explained thoroughly to the respondents at the beginning of their interviews. At the same time, respondents engaged in warm up exercises and could ask questions of the interviewer. This was to attempt to ensure that the respondents fully understood what was being asked of them; in all studies, at the end of the warm up periods, all respondents appeared to understand the tasks.

It can be contested that in order to financially incentivise the respondents they ought to have been informed that the outcomes would be scaled down before they answered the questions. However, had this been done, the respondents may well have processed the questions as if they all had small financial consequences. It was felt that by not knowing the exact scaling down of the money outcomes at the beginning of the study the respondents would mentally process the outcomes as given, and this is what they appeared to be doing during the warm up session. Moreover, by informing the respondents up front that their payments would be consequent on their answers (which was the case, and thus no deception was involved), the respondents would feel in some sense financially incentivised.

If £20,000 was instead assumed to be a life-changing amount of money for the respondents, the Markowitz model would predict a risk preference pattern of AS throughout Table 3, as opposed to that of SA postulated in Table 2. Either way, the overall data better match the prospect theory than the Markowitz predictions.

The results in Table 3 and the analysis that follows it are based upon the proportion of respondents exhibiting each particular risk preference pattern over gains and losses. A much stricter test would look at the proportion of respondents who complied with all four risk attitudes in each test of reflection, as predicted by each theory. When assuming zero money holdings, 28 respondents demonstrated either a risk averse or risk seeking attitude in all four questions; for the reason noted above, those respondents who demonstrated risk neutrality were excluded from the analysis, except the one respondent who was universally risk neutral and was thus consistent with the orthodox model. Under these circumstances, 7% of the respondents were consistent with the orthodox model, 31% with prospect theory, 0% with Markowitz under the assumption that £20,000 is not a life-changing amount of money, and 10% with Markowitz under the assumption that it is a life-changing amount of money. The remaining respondents demonstrated one of all remaining fourfold risk preference patterns. When assuming money holdings of £100,000, 26 respondents could be tested similarly: 4% were consistent with the orthodox model, 58% with prospect theory, 0% with Markowitz under the assumption that £20,000 is not a life-changing amount of money, and 4% with Markowitz under the assumption that it is a life-changing amount of money.

Bouchouicha and Vieider (2017) similarly did not observe the Markowitz prediction of risk seeking increasing with the magnitude of losses.

However, the results do not offer support for the full Markowitz predicted pattern of reflection across gains and losses. According to the Markowitz model, for each level of probability in Table 4 the general trend should be an increasing proportion of AS patterns and a decreasing proportion of SA patterns as outcome size increases. While the proportion of AS patterns does increase somewhat, a decline in the proportion of SA patterns is not generally observed, principally because the prevalence of this pattern is not particularly evident at any outcome level, other than when attached to the lowest probability in the table, as predicted by prospect theory. Evidence in support of Markowitz reflection is even less evident in the health outcome studies reported later in this article. Moreover, over health outcomes, unlike with money outcomes, there was no general trend of increased risk seeking over smaller outcomes in the domain of gains.

The results using the stricter test of the proportion of respondents who complied with all four risk attitudes as predicted by each theory are hereby presented for the questions where the outcomes had either a very high or a very low percentage chance of occurring (i.e. 90% or 10%), because it is at these percentage chances that the full fourfold prospect theory reflection effect is most meant to apply. With an outcome magnitude of £1million, 33 respondents could be tested: 9% of these were fully consistent with the orthodox model, 9% with prospect theory, 3% with Markowitz under the assumption that £1million is not a life-changing amount of money, and 18% with Markowitz under the assumption that it is a life-changing amount of money. With an outcome magnitude of £10,000, 21 respondents could be tested: 5% of these were consistent with the orthodox model, 10% with prospect theory, 0% with Markowitz under the assumption that £10,000 is not a life-changing amount of money, and 24% with Markowitz under the assumption that it is a life-changing amount of money. Finally, with an outcome magnitude of £100, 25 respondents could be tested: 0% of these were consistent with the orthodox model, 32% with prospect theory, and 0% with Markowitz whether or not £100 is assumed to be a life-changing amount of money.

If one were to focus upon twofold reflection of risk aversion for gains and risk seeking for losses over probabilities between 0.7 and 0.9, however, then this second study, irrespective of outcome magnitude, strongly corroborates the previous literature that has reported such an effect.

To reiterate from footnote 2, these decision tasks were explained in detail to all respondents at the beginning of their interviews, where they engaged in warm up exercises. Great care was taken to ensure that all respondents fully understood what was being asked of them, which by the time they embarked on the main questions, they all appeared to do.

Even over money outcomes, Kahneman and Tversky (1979) discussed the possibility that there may be special circumstances where the prospect theory value function is convex for gains and concave for losses. For instance, they wrote that if an individual needs $60,000 to purchase a house, the value function may show a steep rise near the critical value (there are parallels here with the views expressed by Marshall (1920), noted in the first paragraph of this article). One could contend that the studies reported in this article, and perhaps particularly this health-related test, used outcomes that sometimes have extreme possible consequences that may plausibly fall within Kahneman and Tversky’s special circumstances category. The results imply, however, that the chosen outcomes in and of themselves did not generally negate evidence for the prospect theory reflection effect (other than perhaps more people being risk averse when faced with a small probability of winning a very large money amount than the prospect theory reflection effect would predict in the investment questions); indeed, in this valuation-based health-related test, the evidence for the reflection effect was particularly strong.

As with the investment tests reported earlier, the results using the stricter test of the proportion of respondents who complied with all four risk attitudes as predicted by each theory are hereby presented for the questions where the outcomes had 90% and 10% chances of occurring. With an outcome magnitude of 480 months, 47 respondents could be tested: 2% of these were fully consistent with the orthodox model and 36% were consistent with prospect theory. If plus and minus 480 months does not take us far from the origin in Fig. 1, 0% of these respondents were consistent with the Markowitz model; if this number of months takes us far from the origin, 4% of these respondents were consistent with the Markowitz model. With an outcome magnitude of 180 months, 51 respondents could be tested: 10% of these were consistent with the orthodox model and 41% were consistent with prospect theory. If plus and minus 180 months does not take us far from the origin in Fig. 1, 0% of these respondents were consistent with Markowitz; if this number of months takes us far from the origin, 6% of the respondents were consistent with Markowitz. With an outcome magnitude of 36 months, 54 respondents could be tested: 6% of these were consistent with the orthodox model and 59% were consistent with prospect theory. None of these respondents were consistent with the Markowitz predictions, irrespective of whether or not plus and minus 36 months takes us far from the origin in Fig. 1.

That said, if the status quo is an unbearable proposition to the patient, then the desire to undertake a one-shot treatment may be rational in a broad sense of the term irrespective of how many orders of magnitude worse than the status quo is the outcome of treatment failure (assuming that it is possible to have outcomes that are orders of magnitude worse than ‘unbearable’), given that treatment offers at least some prospect of escaping the already unbearable status quo.

Remember, however, that Bouchouicha and Vieider (2017) used a sequence of pairwise choices to elicit certainty equivalencies, and found evidence in support of prospect theory’s fourfold reflection effect.

The difference in the number of SA to AS patterns where significance is reached for the medium and large outcomes is in the opposite direction to that predicted by prospect theory.

The results for pairwise choice that correspond to those presented in footnote 12 for the valuation questions in the stricter test of each theory are hereby presented. In all cases all 60 respondents could be tested. With an outcome magnitude of 480 months, 33% of the respondents were fully consistent with the orthodox model, 10% were consistent with prospect theory, and 2% were consistent with the Markowitz predictions, irrespective of whether or not plus and minus 480 months takes us far from the origin in Fig. 1. With an outcome magnitude of 180 months, 30% were consistent with the orthodox model and 12% were consistent with prospect theory. If plus and minus 180 months does not take us far from the origin in Fig. 1, 0% of these respondents were consistent with Markowitz; if this number of months takes us far from the origin, 2% of the respondents were consistent with Markowitz. With an outcome magnitude of 36 months, 15% were consistent with the orthodox model and 33% were consistent with prospect theory. If plus and minus 36 months does not take us far from the origin in Fig. 1, 5% of these respondents were consistent with Markowitz; if this number of months takes us far from the origin, 3% of the respondents were consistent with Markowitz.

It may be contended that prospect theory was, strictly speaking, developed as a theory of pairwise choice and was not meant to apply to open valuation or pricing tasks. Restricting the theory to pairwise choice would limit its applicability to public policy, and thus the contention here is that it is better to think of it as a general theory, as is often the case. However, if the theory is restricted to pairwise choice, it is noteworthy that the results reported in this article, and those reported by Harbaugh et al. (2009), suggest that it is of limited use, if evidence of the full fourfold reflection effect is an indication of its usefulness, although the results reported by Bouchouicha and Vieder (2017), who used sequences of pairwise choices to elicit certainty equivalents, offer a counter view. That the reflection effect was very much more present in the valuation exercises both in the studies reported here and in Harbaugh et al. (2009) suggests that the prospect theory predictions may be better realised over decision tasks for which the theory was not, strictly speaking, originally developed.

Binmore (1999) contended that on the basis of experiments that he had conducted, orthodox economic theory can only be expected to predict decision making in the laboratory when the decision tasks are easy for respondents to understand, when incentives are adequate and when there is sufficient time allowed for trial-and-error adjustment. The results reported in this article suggest that an additional criterion is that the decision tasks are pairwise choices rather than valuations.

References

Abdellaoui, M. (2000). Parameter-free elicitation of utilities and probability weighting functions. Management Science, 46(11), 1497–1512.

Abdellaoui, M., Bleichrodt, H., & Paraschiv, C. (2007). Loss aversion under prospect theory. A parameter-free measurement. Management Science, 53(10), 1659–1674.

Abdellaoui, M., Bleichrodt, H., & Kammoun, H. (2013). Do financial professionals behave according to prospect theory? An experimental study. Theory and Decision, 74(3), 411–429.

Abellan-Perpiñan, J. M., Bleichrodt, H., & Pinto-Prades, J. L. (2009). The predictive validity of prospect theory versus expected utility in health utility measurement. Journal of Health Economics, 28(6), 1039–1047.

Attema, A. E., & Brouwer, W. B. F. (2008). Can we fix it? Yes we can! But what? A new test of procedural invariance in TTO measurement. Health Economics, 17(7), 877–885.

Attema, A. E., Brouwer, W. B. F., & l’Haridon, O. (2013). Prospect theory in the health domain: A quantitative assessment. Journal of Health Economics, 32(6), 1057–1065.

Attema, A. E., Brouwer, W. B. F., l’Haridon, O., & Pinto, J. L. (2016). An elicitation of utility for quality of life under prospect theory. Journal of Health Economics, 48(July), 121–134.

Bardsley, N., Cubitt, R., Loomes, G., Moffatt, P., Starmer, C., & Sugden, R. (2010). Experimental economics: Rethinking the rules. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Bateman, I., Day, B., Loomes, G., & Sugden, R. (2007). Can ranking techniques elicit robust values? Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 34(1), 49–66.

Baucells, M., & Villasis, A. (2010). Stability of risk preferences and the reflection effect of prospect theory. Theory and Decision, 68(1–2), 193–211.

Beattie, J., & Loomes, G. (1997). The impact of incentives upon risky choice experiments. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 14(2), 155–168.

Becker, G. M., DeGroot, M. H., & Marschak, J. (1964). Measuring utility by a single-response sequential method. Behavioral Science, 9(3), 226–232.

Behavioural Insights Team. (2010). Applying behavioural insights to health. London: Cabinet Office.

Binmore, K. (1999). Why experiment in economics? The Economic Journal, 109(February), F16–F24.

Bleichrodt, H., Pinto, J. L., & Wakker, P. P. (2001). Using descriptive findings of prospect theory to improve prescriptive applications of expected utility. Management Science, 47(11), 1498–1514.

Booij, A. S., van Praag, B. M. S., & van de Kuilen, G. (2010). A parametric analysis of prospect theory’s functionals for the general population. Theory and Decision, 68(1), 115–148.

Bouchouicha, R., & Vieider, F. M. (2017). Accommodating stake effects under prospect theory. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 55(1), 1–28.

Brooks, P., Peters, S., & Zank, H. (2014). Risk behaviour for gain, loss and mixed prospects. Theory and Decision, 77(2), 153–182.

Camerer, C. F., & Hogarth, R. M. (1999). The effects of financial incentives in experiments: A review and capital-labor-production framework. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 19(1), 7–42.

Cohen, M., Jaffray, J.-Y., & Said, T. (1987). Experimental comparison of individual behavior under risk and uncertainty for gains and for losses. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 39(1), 1–22.

di Mauro, C., & Maffioletti, A. (2004). Attitudes to risk and attitudes to uncertainty: Experimental evidence. Applied Economics, 36(4), 357–372.

Fiegenbaum, A., & Thomas, H. (1988). Attitudes toward risk and the risk-return paradox: Prospect theory explanations. Academy of Management Journal, 31(1), 85–106.

Guthrie, C. (2003). Prospect theory, risk preference, and the law. Northwestern University Law Review, 97(3), 1115–1163.

Harbaugh, W. T., Krause, K., & Vesterlund, L. (2002). Risk attitudes of children and adults: Choices over small and large probability gains and losses. Experimental Economics, 5(1), 53–84.

Harbaugh, W. T., Krause, K., & Vesterlund, L. (2009). The fourfold pattern of risk attitudes in choice and pricing tasks. The Economic Journal, 120(545), 595–611.

Hershey, J. C., & Schoemaker, P. J. H. (1980). Prospect theory’s reflection hypothesis: A critical examination. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 25(3), 395–418.

Hertwig, R., & Ortmann, A. (2001). Experimental practices in economics: A methodological challenge for psychologists? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 24(3), 383–451.

Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. London: Allen Lane.

Kahneman, D., & Sugden, R. (2005). Experienced utility as a standard of policy evaluation. Environmental and Resource Economics, 32(1), 161–181.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: An analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47(2), 263–292.

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. (1990). Experimental tests of the endowment effect and the Coase theorem. Journal of Political Economy, 98(6), 1325–1348.

Laury, S. K., & Holt, C. A. (2005). Further reflections on prospect theory. Working paper 06–11. Andrew Young School of Policy Studies Research Paper Series, Georgia State University.

Levy, M., & Levy, H. (2002). Prospect theory: Much ado about nothing? Management Science, 48(10), 1334–1349.

Luce, R. D. (2000). Utility of gains and losses: Measurement – Theoretical and experimental approaches. London: Lawrence Erlbaum Publishers.

Markowitz, H. (1952). The utility of wealth. Journal of Political Economy, 60(2), 151–158.

Marshall, A. (1920). Principles of economics. London: Macmillan.

McNeil, B. J., Pauker, S. G., Sox, H. C., & Tversky, A. (1982). On the elicitation of preferences for alternative therapies. New England Journal of Medicine, 306(21), 1259–1262.

Oliver, A. (2003). The internal consistency of the standard gamble: Tests after adjusting for prospect theory. Journal of Health Economics, 22(4), 659–674.

Oliver, A. (2006). Further evidence of preference reversals: Choice, valuation and ranking over distributions of life expectancy. Journal of Health Economics, 25(5), 803–820.

Oliver, A. (2013). Testing the rate of preference reversal in personal and social decision making. Journal of Health Economics, 32(6), 1250–1257.

Oliver, A. (2017). The origins of behavioural public policy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Oliver, A., & Wolff, J. (2014). Are people consistent when trading time for health? Economics and Human Biology, 15, 41–46.

Parducci, A., & Weddell, D. (1986). The category effect with rating scales: Number of categories, number of stimuli and method of presentation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 12(4), 496–516.

Rabin, M. (2000). Risk aversion and expected utility theory: A calibration theorem. Econometrica, 68(5), 1281–1292.

Schoemaker, P. J. H. (1990). Are risk-attitudes related across domains and response modes? Management Science, 36(12), 1451–1463.

Scholten, M., & Read, D. (2014). Prospect theory and the ‘forgotten’ fourfold pattern of risk preferences. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 48(1), 67–83.

Seidl, C. (2002). Preference reversal. Journal of Economic Surveys, 16(5), 621–655.

Thaler, R. H. (2015). Misbehaving: The making of behavioural economics. New York: Penguin Random House.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1992). Advances in prospect theory: Cumulative representation of uncertainty. Journal of Risk and Uncertainty, 5(4), 297–323.

van Osch, S. M. C., Wakker, P. P., van den Hout, W. B., & Stiggelbout, A. M. (2004). Correcting biases in standard gamble and time tradeoff utilities. Medical Decision Making, 24(5), 511–517.

van Osch, S. M. C., van den Hout, W. B., & Stiggelbout, A. M. (2006). Exploring the reference point in prospect theory: Gambles for length of life. Medical Decision Making, 26(4), 338–346.

Wehrung, D. A. (1989). Risk taking over gains and losses: A study of oil executives. Annals of Operations Research, 19(1), 115–139.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the editor, Kip Viscusi, and an anonymous reviewer for their comments on previous versions of this article.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Oliver, A. Your money and your life: Risk attitudes over gains and losses. J Risk Uncertain 57, 29–50 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-018-9284-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-018-9284-4

Keywords

- Expected utility theory

- Fourfold pattern of risk preferences

- Markowitz

- Money and health

- Prospect theory

- Reflection effect

- Risk