Abstract

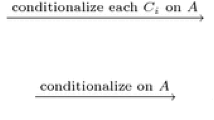

This paper extends our earlier work on reverse Bayesianism by relaxing the assumption that decision makers abide by expected utility theory, assuming instead weaker axioms that merely imply that they are probabilistically sophisticated. We show that our main results, namely, (modified) representation theorems and corresponding rules for updating beliefs over expanding state spaces and null events that constitute “reverse Bayesianism,” remain valid.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We thank Graeme Doole for calling our attention to this paragraph in Lancaster’s article.

Fishburn (1970) Ch. 12 discusses a construction of a state space along similar lines. He does not, however, discuss an extension of the set of acts to include conceivable acts.

Formally, \(p\in {\Delta } \left ( C\right ) \) is a function \(p:C\rightarrow \left [ 0,1\right ] \) satisfying \({\Sigma }_{c\in C}p\left ( c\right ) =1.\) Notice that with this definition of Δ(C) we have that, for any \(C\subset C^{\prime } \), any p∈Δ(C) is also an element of \({\Delta } (C^{\prime } )\) with p(c)=0 for all \(c\in C^{\prime } -C\). Likewise, \(q\in {\Delta } (C^{\prime })\) is an element of Δ(C) if q(c)=0 for all \(c\in C^{\prime } -C\).

Fishburn’s (1970) notion of excluded states is analogous to our non-feasible states.

Below, \(f^{\prime } =f\) on an event E means that \(f^{\prime } (s)=f(s)\) for all s∈E (i.e., it is defined pointwise for the states in E).

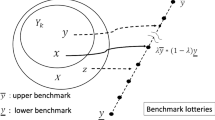

A function V is strictly monotonic if V(p)≥V(q) whenever p dominates q according to first-order stochastic dominance, with strict inequality in the case of strict dominance, and V is mixture continuous if \(V(\alpha p+\left ( 1-\alpha \right ) q)\) is continuous in α for all p and q.

Suppose that ∣F∣=r and \(\mid F^{^{\prime } }\mid =k>r.\) Let \(s=\left ( c_{1},...,c_{k}\right ) \in C^{F^{\prime }}\), then \(\boldsymbol {P}_{C^{F}}\left ( s\right ) =\left ( c_{1},...,c_{r}\right ) \in C^{F}.\)

Gul (1991) axiomatized a model of disappointment aversion under risk. The argument here is analogous to that of Gul except that here it is cast in terms of uncertainty.

References

Anscombe, F.J., & Aumann, R.J. (1963). A definition of subjective probability. Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 43, 199–205.

Epstein, L., & Schneider, M. (2003). Recursive multiple-priors. Journal of Economic Theory, 113, 1–31.

Fishburn, P.C. (1970). Utility Theory for Decision Making. New York: Wiley.

Grant, S., & Polak, B. (2006). Bayesian beliefs with stochastic monotonicity: an extension of Machina and Schmeidler. Journal of Economic Theory, 130, 264–282.

Gul, F. (1991). A theory of disappointment aversion. Econometrica, 59, 667–686.

Karni, E., & Schmeidler, D. (1991). Utility theory with uncertainty. In Hildenbrand, W., amp; Sonnenschein, H. (Eds.) Handbook of Mathematical Economics, Vol. 4. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers B.V.

Karni, E, & Vierø, M.-L. (2013). “Reverse Bayesianism”: a choice-based theory of growing awareness. American Economic Review, 103, 2790–2810.

Kochov, A. (2010). A model of limited foresight. Working paper, University of Rochester.

Lancaster, K.J. (1966). A new approach to consumer theory. Journal of Political Economy, 74, 132–157.

Machina, M., & Schmeidler, D. (1992). A more robust definition of subjective probability. Econometrica, 60, 745–780.

Machina, M., & Schmeidler, D. (1995). Bayes without Bernoulli: simple conditions for probabilistically sophisticated choice. Journal of Economic Theory, 67, 106–128.

Ortoleva, P. (2012). Modeling the change of paradigm: non-Bayesian reaction to unexpected news. American Economic Review, 102, 2410–2436.

Savage, L.J. (1954). The Foundations of Statistics. New York: Dover Publications.

Schmeidler, D., & Wakker, P. (1987). Expected utility and mathematical expectation. In Eatwell, J., Milgate, M., amp; Newman, P. (Eds.) The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics. New York: Macmillan Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We thank Graeme Doole, Asen Kochov, and Jacob Sagi for comments.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Karni, E., Vierø, ML. Probabilistic sophistication and reverse Bayesianism. J Risk Uncertain 50, 189–208 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-015-9216-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11166-015-9216-5