Abstract

This paper analyzes a sample of Section 1, Sherman Act price fixing cases brought by the US Department of Justice between 1961 and 2013. Over 500 cartels were prosecuted during this period. The determinants of cartel formation and cartel breakup are estimated, including analysis of the impact of the discount rate, business cycles, and antitrust policy. We find that cartels are more likely to break up during periods of high real interest rates, presumably because higher interest rates are associated with greater impatience. The adoption of a stronger amnesty policy has no significant impact on cartel breakup over this period, although the results suggest some association with lower cartel formation rates.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Baer and Hosko (2013, p. 2).

This policy provides for full amnesty from criminal prosecution for the first member of a cartel to report a previously unknown cartel to the Justice Department, encouraging a “race to the courthouse door” among cartel members. See Department of Justice, Antitrust Division, Leniency Policies http://www.justice.gov/atr/public/criminal/leniency.htm for the current corporate and individual amnesty policies of the DOJ. See Hammond (2005) for a discussion of these policies and their impact on antitrust enforcement.

Spagnolo (2000, 2007) shows that the impact of leniency is less obvious than the treatment here suggests. In particular, partial amnesty can increase the set of collusive equilibria and the potential collusive profits that are available to a cartel, which makes collusion easier and therefore presumably more durable. Aubert et al. (2006) discuss the relationship between the design of leniency programs and their impact on both cartel stability and firm performance. Miller (2009) discusses strategic responses to leniency. Harrington and Chang (2009) discuss the impact of leniency on both breakup and formation.

There is a literature that focuses on the role of leaders (e.g., Saudi Arabia or US Steel) in facilitating collusion and another strand that focuses on “maverick” firms as impediments to collusion (Baker 1989, 2002). Both of these strands presume that there is heterogeneity that affects collusive stability.

See Levenstein and Suslow (2011, p. 478) for an overview of empirical examinations of the impact of demand fluctuations on cartel breakup. Experimental analysis in Feinberg and Snyder (2002) finds that observable demand downturns have little impact on the ability to sustain collusion, while unobservable negative shocks undermine collusion.

Part of the reason this remains a puzzle is that the theoretical literature does not generally address the question of when an industry would need to communicate explicitly in order to maintain a collusive equilibrium. Instead it asks whether collusion, either tacit or explicit, is an equilibrium. Our focus is on explicit collusive agreements.

Alexander (1994) and Krepps (1997) examine the impact of changes in antitrust policy on cartel formation under the National Industrial Recovery Act. Levenstein and Suslow (2006a, p. 67) summarize: “Many studies report that a cartel was formed during a period of falling prices, but this is not always, or even usually, associated with falling demand (either for the particular product or in the general economy). Instead, falling prices were often the result of entry or the integration of previously distinct markets.” See also, Levenstein and Suslow (2011).

Most prosecuted cartels have more than one CCH record because there are often separate convictions for different firms as well as individual defendants. We have consolidated these into cartel-level observations.

We are extremely grateful to Bryant and Eckard for their willingness to share their data with us. Note that they treat no contest pleas as guilty pleas (Bryant and Eckard 1991, p. 532).

The Byrant and Eckard sample excluded bid-rigging cases. We have gone back to 1961 to collect CCH records on bid rigging cases, as described below. We have also added additional cases from that period that had been appealed and therefore were not included in their original sample.

As we have written previously about studies using these and similar samples, “these estimates … must be treated with caution, as they are not based on random samples. To the contrary, because cartels are often secretive and even illegal, sample selection reflects the legal regime in which the cartels operated. In some cases, samples are literally selected by prosecutors; in such cases we simply do not know whether cartels that run afoul of legal authorities are similar to or different from cartels that manage to escape unnoticed” (Levenstein and Suslow 2006a, p. 44). The same caution applies to the analysis in this paper.

Our data set is, at least in principle, inclusive of all of the observations in Miller (2009).

There are cases of earlier international cartel prosecutions (potash, shipping), but they are rare and mostly pre-date World War II.

Other cartel datasets do include cause of cartel breakup. See, for example, Levenstein and Suslow (2011).

Levenstein and Suslow (2006a, p. 60), “Another explanation for the prevalence of cartels in unconcentrated industries is the role played by trade associations. In the case studies and in contemporary international cartels, industry associations were involved whenever the number of cartel participants was large.”

See Levenstein and Suslow (2006b, pp. 26–27), for discussion of the role of industry associations in US and European cartels over the last century.

Calculated from data provide by Bryant and Eckard (1991).

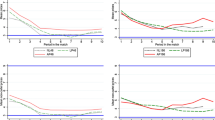

Kaplan–Meier curves are commonly used in demographic and bio-medical studies to display the probability of an event (e.g., death) in a population. See Rich et al. (2010).

The first cartel in the full sample was formed in 1932, but was dropped for missing information.

Cartels may also be discovered for non-economic reasons, such as when there is a whistleblower.

We use these two measures in our previous study of the determinants of international cartel breakup (Levenstein and Suslow 2011) and find that they have a significant impact.

Note that this differs somewhat from the measure used in Levenstein and Suslow (2011). Most of the firms in that study were publicly traded, so it was possible to obtain financial information for the specific firms in the cartel. That was not possible for this sample, so instead we rely on data for firms in the industry.

The minimum value for this variable belongs to "Moving and Storage of Household Goods" (NAICS 4931) when some firm had negative cash equal 261.6 times its required interest payments. Presumably this reflects both large losses and small required interest payments. This one observation is clearly an outlier in the entire sample, as it is three times larger (in absolute value) than the closest observation in the sample.

Recession years are defined by the NBER business cycle reference dates, from 1857 to the present, and can be found at US Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions, National Bureau of Economics Research, www.nber.org/cycles.html.

The HP filter fits a smooth nonlinear trend curve to a time series by decomposing it into a nonstationary trend component and a stationary cyclical component.

Given the insignificant coefficient on the number of members and concern that excluding cartels for which we do not have the number of members might bias our results, we have estimated the regressions in Tables 4 and 5 on a sample that includes the 18 cartels for which we do not have a measure of the number of member of firms (and drops that variable from the regression). The size and significance of the other coefficients do not change as a result of the change in sample.

Harrington and Chang (2012) examine the impact of leniency on enforcement when the antitrust authority has limited resources.

References

Alexander, B. J. (1994). The impact of the National Industrial Recovery Act on cartel formation and maintenance costs. Review of Economics and Statistics, 76(2), 245–254.

Aubert, C., Rey, P., & Kovacic, W. E. (2006). The impact of leniency and whistle-blowing programs on cartels. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 24(6), 1241–1266.

Baer, W. J. B. & Hosko, R. T. (2013). Cartel prosecution: Stopping price fixers and protecting consumers, statement by Baer (Assistant Attorney General, Antitrust Division) and Hosko (Assistant Director, Criminal Investigative Division, Federal Bureau of Investigation), before the Subcommittee on Antitrust, Competition Policy and Consumer Rights, Committee on the Judiciary, United States Senate Hearing, November 14, 2013.

Baker, J. B. (1989). Identifying cartel policing under uncertainty: The US steel industry, 1933–1939. Journal of Law and Economics, 32(2), 47–76.

Baker, J. B. (2002). Mavericks, mergers, and exclusion: Proving coordinated competitive effects under the antitrust laws. New York University Law Review, 77(1), 135–203.

Bos, I., & Harrington, J. (2010). Endogenous cartel formation with heterogeneous firms. Rand Journal of Economics, 41(1), 92–117.

Bradburd, R. M., & Over, A. M. (1982). Organizational costs, ‘Sticky Equilibria’, and critical levels of concentration. Review of Economics and Statistics, 64(1), 50–58.

Bruttel, L. V. (2009). The critical discount factor as a measure for cartel stability? Journal of Economics, 96(2), 113–136.

Bryant, P. G., & Eckard, E. W. (1991). Price fixing: The probability of getting caught. Review of Economics and Statistics, 73(3), 531–536.

d’Aspremont, C., Jacquemin, A., Gabszewicz, J., & Weymark, J. (1983). On the stability of collusive price leadership. Canadian Journal of Economics, 16(1), 17–25.

Dal Bo, P. (2005). Cooperation under the shadow of the future: Experimental evidence from infinitely repeated games. American Economic Review, 95(5), 1591–1604.

Dal Bo, P., & Frechette, G. R. (2011). The evolution of cooperation in infinitely repeated games: Experimental evidence. American Economic Review, 101(1), 411–429.

Dick, A. R. (1996). Identifying contracts, combinations, and conspiracies in restraint of trade. Managerial and Decision Economics, 17(2), 203–216.

Feinberg, R., & Husted, T. (1993). An experimental test of discount-rate effects on collusive behavior in duopoly markets. Journal of Industrial Economics, 41(2), 153–160.

Feinberg, R., & Snyder, C. (2002). Collusion with secret price cuts: An experimental investigation. Economics Bulletin, 3(6), 1–11.

Fershtman, C., & Pakes, A. (2000). A dynamic oligopoly with collusion and price wars. Rand Journal of Economics, 31(2), 207–236.

Filson, D., Keen, E., Fruits, E., & Borcherding, T. (2001). Market power and cartel formation: Theory and an empirical test. Journal of Law and Economics, 44(2), 465–480.

Gallo, J. C., Craycraft, J. L., Dau-Schmidt, K., & Parker, C. A. (2000). Department of Justice Antitrust Enforcement, 1955–1997: An empirical study. Review of Industrial Organization, 17(1), 75–133.

Green, E. J., & Porter, R. H. (1984). Noncooperative collusion under imperfect price information. Econometrica, 52(1), 87–100.

Hammond, S. 2005. An update of the antitrust division’s criminal enforcement program. Paper presented before the American Bar Association Section of Antitrust Law Cartel Enforcement Roundtable, Washington, DC, November 16. http://www.justice.gov/atr/public/speeches/213247.pdf

Harrington, J. E., Jr. (1989). Collusion among asymmetric firms: The case of different discount factors. International Journal of Industrial Organization, 7(2), 289–307.

Harrington, J. E., Jr, & Chang, M.-H. (2009). Modeling the birth and death of cartels with an application to evaluating competition policy. Journal of the European Economic Association, 7(6), 1400–1435.

Harrington, J. E., Jr., & Chang, M.-H. (2012). Endogenous antitrust enforcement in the presence of a corporate leniency program. Working paper.

Hay, G. A., & Kelley, D. (1974). An empirical survey of price fixing conspiracies. Journal of Law and Economics, 17(1), 13–38.

Hodrick, R. J., & Prescott, E. C. (1997). Postwar US business cycles: An empirical investigation. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 29(1), 1–16.

Holt, C. A. (1985). An experimental test of the consistent-conjectures hypothesis. American Economic Review, 75(3), 314–325.

Krepps, M. B. (1997). Another look at the impact of the National Industrial Recovery Act on cartel formation and maintenance costs. Review of Economics and Statistics, 79(1), 151–154.

Levenstein, M. C., & Suslow, V. Y. (2006a). What determines cartel success? Journal of Economic Literature, 44(1), 43–95.

Levenstein, M. C., & Suslow, V. Y. (2006b). Cartel bargaining and monitoring: The role of information sharing. In The Pros and Cons of information sharing (Konkurrensverket, Swedish Competition Authority)

Levenstein, M. C., & Suslow, V. Y. (2011). Breaking up is hard to do: Determinants of cartel duration. Journal of Law and Economics, 54(2), 455–492.

Levenstein, M. C., & Suslow, V. Y. (2015). Cartels and collusion: Empirical evidence. In R. D. Blair & D. D. Sokol (Eds.), Oxford handbook on international antitrust economics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Miller, N. H. (2009). Strategic leniency and cartel enforcement. American Economic Review, 99(3), 750–768.

Murnighan, J. K., & Roth, A. E. (1983). Expecting continued play in prisoner’s dilemma games: A test of several models. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 27(2), 279–300.

Posner, R. A. (1970). A statistical study of antitrust enforcement. Journal of Law and Economics, 13(2), 365–419.

Ravn, M. O., & Uhlig, H. (2002). On adjusting the Hodrick–Prescott filter for the frequency of observations. Review of Economics and Statistics, 84(2), 371–376.

Rich, J. T., G N, J., Paniello, R. C., Voelker, C. C. J., Nussenbaum, B., & Wang, E. W. (2010). A practical guide to understanding Kaplan-Meier curves. Otolaryngology-Head Neck Surgery, 143(3), 331–336.

Rotemberg, J. J., & Saloner, G. (1986). A supergame-theoretic model of price wars during booms. American Economic Review, 76(3), 390–407.

Roth, A. E., & Murnighan, J. K. (1978). Equilibrium behavior and repeated play of the prisoner’s dilemma. Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 17(2), 189–198.

Sabater-Grande, G., & Georgantzis, N. (2002). Accounting for risk-aversion in repeated prisoners’ dilemma games: An experimental test. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 48(1), 37–50.

Schmitt, N., & Weder, R. (1998). Sunk costs and cartel formation: Theory and application to the dyestuff industry. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 36, 197–220.

Spagnolo, G. (2000). Self-defeating antitrust laws: How leniency programs solve Bertrand’s paradox and enforce collusion in auctions. Working paper no. 52.2000. Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei, Milan.

Spagnolo, G. (2007). Leniency and whistleblowers in antitrust. In P. Buccirossi (Ed.), Handbook of antitrust economics (pp. 259–304). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Stigler, G. (1964). A theory of oligopoly. Journal of Political Economy, 72(1), 44–61.

Tirole, J. (1988). The theory of industrial organization. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Acknowledgments

We are extremely grateful for the research assistance of Brian Apel, Danial Asmat, Sasha Brodsky, Yulia Chhabra, Anna Walker, and Nathan Wilson. The paper also benefitted greatly from comments by Robert Feinberg as well as discussants and participants at the 2013 conference in honor of Robert Lanzilotti, University of Florida, and the 2014 International Industrial Organization Conference.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Levenstein, M.C., Suslow, V.Y. Price Fixing Hits Home: An Empirical Study of US Price-Fixing Conspiracies. Rev Ind Organ 48, 361–379 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-016-9520-5

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11151-016-9520-5