Abstract

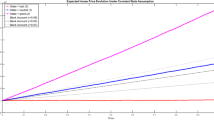

This study demonstrates that taking into account heterogeneous investment horizons will improve our understanding of housing price and trading dynamics. Using an OLG (Overlapping Generations) model in which agents have heterogeneous preferences and investment horizons, with transaction costs, short term investors are more sensitive to changes in economic fundamentals and are less likely to own (and trade) in a declining market. The model predicts that the ownership composition contains information about current and future house prices and trading dynamics. Empirically, we find that home owners’ expected holding horizons co-vary negatively with house prices, and they also predict future (short term) returns.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

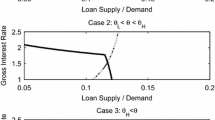

One can show that when all short-horizon (or long-horizon) agents have homogeneous valuations, there are a fixed (smaller) proportion of short horizon owners in equilibrium. Housing price appreciation (or the rate of return) is not associated and cannot be predicted by the relative short-horizon demand.

Please refer to Hong and Stein (2007) for a detailed summary.

For convenience, we are assuming there is a long-lived risk neutral landlord in this economy that does not consume housing and is passively collecting rents in the rental market.

This seems to be a different take from the traditional housing demand literature, in which household formation (and thus their expected duration) is an endogenous function of market conditions. However, we view the exogenously fixed holding horizon as the assumption conditional on the effect of market conditions on household formation. That is, given the prevalent conditions, we assume there is still cross-sectional heterogeneity in potential home buyers’ ex ante holding horizon expectations, which are mainly driven by their demographic characteristics. Nevertheless, there remains the caveat that the holding horizon expectations might be systematically correlated with prevalent market conditions through the household formation channel. In the empirical section, we take that into account for test identification.

The source is from National Association of Homebuilders and the table is available on www.housingeconomics.com.

In AHS, metropolitan areas are categorized by the 1980 Primary Metropolitan Statistical Area (PMSA) definition.

For later tests, we use the logged values as regressors for all variables in levels.

There are MSA years in our sample when we do not observe any home purchases (according to the American Housing survey). In such situations, we use the next adjacent MSA year observation to construct housing return and the change in the expected duration for our main regressions. The missing observations appear to be randomly distributed over the 20 year period (1985–2005), implying that our final panel is unlikely to be biased in terms of more missing observations in a bust period. In addition, we include as a control variable in our main regressions the number of years of difference between two adjacent observations within each MSA.

We omit marital status and family size which are potentially important determinants of duration. That is because those two variables are only observed at the time of survey in our data but not at the actual time of purchase.

The average price variable is defined as the average transaction price per square foot for all observed sales for a given purchase year in an MSA from the American Housing Survey.

We use the lagged MSA level income, the lagged unemployment, a set of lagged demographics, lagged price, lagged interest rates and inflation measures (CPI) as the explanatory variables. The R2 in the regression is 41 %.

One might notice that the R2s in panel B are astonishingly high. Recall these are regressions of the predicted price changes based on observable macro variables. Specifically, the R2 in the first stage regression where we predict the price is 41 %. One way to interpret is that the given independent variables in panel B explain nearly 41 % of the total price changes, conditional on the current price level.

References

Amihud, Y., & Mendelson, H. (1986). Asset pricing and the bid-ask spread. Journal of Financial Economics, 17, 223–249.

Boehm, T. P. (1981). Tenure choice and expected mobility: A synthesis. Journal of Urban Economics, 10, 375–389.

Case, K. E., & Shiller, R. J. (1988). The behavior of home buyers in boom and post boom markets, Working paper NBER Working Paper Series, NO. 2748.

Case, K. E., & Shiller, R. J. (1989). The efficiency of the market for single-family homes. American Economic Review, 79, 125–137.

Case, K. E., Quigley, J. M., & Shiller, R. J. (2003). Home-buyers, housing and the macroeconomy, Asset Prices and Monetary Policy (pp. 149–188). Canberra: Reserve Bank of Australia.

Cauley, S. D., & Pavlov, A. D. (2002). Rational delays: the case of real estate. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics, 24, 143–165.

Cutler, D. M., Poterba, J. M., & Summers, L. H. (1990). Speculative dynamics and the role of feedback traders. American Economic Review, 80, 63–68.

Engelhardt, G. V. (2003). Nominal loss aversion, housing equity constraints, and household mobility: evidence from the United States. Journal of Urban Economics, 53, 171–195.

Genesove, D., & Mayer, C. J. (1997). Equity and time to sale in the real estate markets. American Economic Review, 87, 255–269.

Genesove, D., & Mayer, C. J. (2001). Loss aversion and seller behavior: evidence from the housing market. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 116, 1233–1260.

Harrison, J. M., & Kreps, D. M. (1978). Speculative investor behavior in a stock market with heterogeneous expectations. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 92, 323–336.

Haurin, D., & Gill, H. L. (2002). The impact of transaction costs and the expected length of stay on homeownership. Journal of Urban Economics, 51, 563–584.

Hong, H., & Stein, J. C. (2007). Disagreement and the stock market. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21, 109–128.

Hong, H., Scheinkman, J. A., & Xiong, W. (2006). Asset float and speculative bubbles. Journal of Finance, 61, 1073–1117.

Ioannides, Y. M., & Kan, K. (1996). Structural estimation of residential mobility and housing tenure choice. Journal of Regional Science, 36, 335–363.

Kahneman, D., & Tversky, A. (1979). Prospect theory: an analysis of decision under risk. Econometrica, 47, 236–291.

Kan, K. (1999). Expected and unexpected residential mobility. Journal of Urban Economics, 45, 72–96.

Krainer, J. (2001). A theory of liquidity in residential real estate markets. Journal of Urban Economics, 49, 32–53.

Lamont, O. A., & Stein, J. C. (1999). Leverage and house-price dynamics in U.S. cities. Rand Journal of Economics, 30, 498–514.

Meese, R. A., & Wallace, N. (1994). Testing the present value relation for housing prices: should i leave my house in San Francisco? Journal of Urban Economics, 35, 245–266.

Novy Marx, R. (2009). Hot and cold markets. Real Estate Economics, 37, 1–22.

Ortalo-Magne, F., & Rady, S. (2006). Housing market dynamics: on the contribution of income shocks and credit constraints. Review of Economic Studies, 73, 459–485.

Qian, W. (2012). Why do sellers hold-out in the down market? An option-based explanation, Real Estate Economics, forthcoming.

Saiz, A. (2010). The geographic determinants of housing supply. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125, 1253–1296.

Scheinkman, J. A., & Xiong, W. (2003). Overconfidence and speculative bubbles. Journal of Political Economy, 111, 1183–1219.

Shelton, J. P. (1968). The cost of renting versus owning a home. Land Economics, 44, 59–72.

Sinai, T., & Souleles, N. S. (2005). Owner occupied housing as a hedge against rent risk. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 120, 763–789.

Stein, J. C. (1995). Prices and trading volume in the housing market: a model with down-payment effects. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 110, 379–406.

Wheaton, W. C. (1990). Vacancy, search and prices in a housing market matching model. Journal of Political Economy, 98, 1270–1292.

Williams, J. T. (1995). Pricing real assets with costly search. Review of Financial Studies, 8, 55–90.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

We thank Jonathan Berk, Shaun Bond, Thomas Davidoff, Yongheng Deng, Piet Eichholtz, David Geltner, Dwight Jaffee, Tim Riddiough, Johan Walden, Nancy Wallace, Bernard Yeung and Erkan Yonder, as well as seminar participants at the University of California, Berkeley, BGI, Concordia University, the research symposium at Maastricht University, National University of Singapore, Rice University and Moody’s KMV for helpful discussions and comments. Wenlan Qian is also affiliated with the Risk Management Institute and the Institute of Real Estate Studies at the National University of Singapore, and acknowledges the financial support from the academic research grant (R-315000-079-133) at the National University of Singapore. All errors are ours alone.

Appendix

Appendix

A Proof of Lemma 1

In the presence of private consumption benefits associated with home ownership, consumers will be indifferent between paying the market rent and live in the rental market and owning by paying the rental cost adjusted for the idiosyncratic private value. The indifference reservation price for each type of consumers then consists of a component that equals the rental cost given the consumer’s horizon. In addition, since owners are entitled to capital gains/losses associated with asset ownership, their reservation price also incorporates the expected price at time of sale given their different horizons. Therefore each short horizon buyer i and every long horizon buyer j have the following valuations,

where r s,t ,g s,t , r l,t and g l,t are defined as in equation (1). Essentially the first term on both equations in (A1) refers to the buyer’s willingness to pay for housing consumption, after adjusting for buyer-specific private values associated with ownership. The second term in both equations of (A1) is the capital gains component that is specific to the buyer’s holding horizon, net of transaction cost.

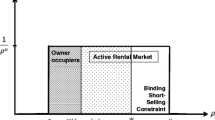

Any potential buyer will only become owner if his/her valuation is greater than or equal to the market price P t . That implies the individual demand for owner-occupied housing is \( {I_{{{P_{s,i,t }}\geqslant {P_t}}}} \) for a short horizon buyer i, and is \( {I_{{{P_{l,j,t }}\geqslant {P_t}}}} \) for a long horizon buyer j. Aggregating the individual demand leads to the following,

Direct calculation of the conditional expectation of a uniform distribution will give the result in Equation (2). Q.E.D.

B Proof of Proposition 1

First we normalize the equilibrium price by the market rent level, i.e., define \( {p_t}\equiv \frac{P_t }{R_t } \). Since \( {R_{t+1 }}={R_t}{Y_t} \), we can eliminate the rent levels in the valuation equations, in which the rent growth rate will be the only state variable. With the equilibrium concept defined to be a steady-state stationary equilibrium, the equilibrium price-to-rent ratio to be solved involves two unknown values and we define them as p L and p H. Using the transition matrix of the rent growth rate, one can easily write-out the normalized valuation equations (by dividing (1) and (A1) by the rent level) as functions of λ,Y L, Y H along with other model primitives, as in (5). Scaling the price by the rent level does not change the distribution properties of the private values as well as buyers’ valuations, so the aggregate demand for each type of buyers is obtained again by calculating the conditional expectation of a uniform random variable (similar to equation (A2)), and one can easily verify the formula in (4).

The next step in solving the equilibrium is to employ the market clearing condition. Note that although the owner-occupied housing market has a fixed size Q, not all housing units are available for sale at any point in time. This is due to the fact that long horizon owners will hold the houses for two periods until the end of their life cycle. As a result, the portion of the owner-occupied housing stock that is absorbed by the long horizon buyers in the previous period will not be for sale during this period, which effectively reduces the housing supply. In the stationary equilibrium, the expected reduction in housing supply equals the probability weighted average of the long horizon’s demand during the previous period. Then the market clearing conditions as in (3) obtain and the equilibrium price (pair) is the solution to that system. Q.E.D.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Edelstein, R., Qian, W. Short-Term Buyers and Housing Market Dynamics. J Real Estate Finan Econ 49, 654–689 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-012-9395-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11146-012-9395-7