Abstract

I investigate the link between dividend taxes and stock prices in a global setting. Based on findings from an open-economy after-tax capital asset pricing model, I predict that, when the U.S. cut its dividend tax rate in 2003, stock prices will increase for high-dividend yield foreign firms that are eligible for a U.S. income tax treaty. I examine returns for firms headquartered in treaty countries and find results consistent with this prediction. In further tests, I find that the same relation does not hold for firms in nontreaty countries. My paper is the first to provide direct evidence about whether and how dividend taxes affect equity prices across an integrated global economy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

As worldwide capital markets continue to integrate, understanding how equity prices are determined in a global setting becomes increasingly important. While research in this area has examined numerous issues, analytical models suggest taxes may also be important (Brennan 1970; Desai and Dharmapala 2011; Amiram and Frank 2016). Specifically, the open-economy after-tax capital asset pricing model (CAPM) suggests that, under certain conditions, changes in dividend taxation in one country can lead to lower dividend tax capitalization and higher equity prices in foreign countries (Desai and Dharmapala 2011; Amiram and Frank 2016). If this is the case, it has implications for asset pricing, corporate finance and policymaking.

To document whether dividend tax rate cuts in one country are associated with increases in equity prices in other countries, I examine the equity returns of foreign firms around the 2003 Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act (JGTRRA). JGTRRA reduced the top individual dividend tax rate from 38.6% to 15% for U.S. taxpayers. The reduced rate applied to dividends received from U.S. firms and foreign firms that had a tax treaty with the United States (hereafter, treaty firms). As a result of JGTRRA, I predict stock prices for certain treaty firms will increase. This prediction is based on the following logic. According to the open-economy after-tax CAPM, the price of a risky asset is partially determined by its expected dividend yield. The tax rate used to capitalize the expected dividend yield into stock prices is based on the weighted average of each investor’s dividend tax rate on the risky asset, where the weights are determined by investor wealth (Desai and Dharmapala 2011). Because JGTRRA decreased U.S. investors’ dividend tax rate on dividends from treaty firms, the weighted average tax rate on these assets should decrease. This should lead to an increase in equity prices for high-dividend yield stocks in treaty countries.

While the open-economy after-tax CAPM suggests dividend tax changes in one country can affect equity prices in another country, there are reasons why prices may not change. First, the open-economy after-tax CAPM shows that the size of the price reaction depends on the wealth of investors affected by the tax rate cut. If the wealth of investors affected is small, prices may move only slightly, making changes difficult to detect in the data. For example, the price reaction may be muted because a large amount of U.S. investor wealth is held in tax-exempt institutions or in tax-qualified accounts, such as pensions and tax-deferred retirement accounts (Sialm 2009). A second reason foreign country stock prices may not change is investor home bias. This phenomenon, where investors allocate a larger than expected fraction of their wealth to domestic equities (Karolyi and Stulz 2003), could dampen the effect of the dividend tax rate cut on treaty country equity prices.

To test whether the tax cut led to an increase in equity prices, I examine cumulative abnormal returns (CARs) for treaty country firms around the passage of JGTRRA. I begin by examining CARs for value-weighted portfolios of treaty country firms based on dividend yield. I find that portfolio CARs are increasing in dividend yield around the time of the dividend tax rate cut. I use multivariate analysis to test an additional hypothesis that the association between dividend yield and CAR will be stronger for securities with greater capital market integration (nonmicrocap firms), compared to securities with limited capital market integration (microcap firms). This prediction is partially motivated by results in Fama and French (2012), which suggest it is possible that “integrated global pricing does not extend to microcaps” (p. 466). I find that the positive relation between CARs and dividend yield only exists for nonmicrocap firms. Overall, the portfolio and multivariate results provide evidence that the passage of JGTRRA is associated with a reduction in dividend tax capitalization for certain firms in treaty countries.

I also examine whether there is a stock price reaction during the event window for firms headquartered in nontreaty countries. The open-economy after-tax CAPM predicts stock prices for firms in nontreaty countries should not change due to the tax cut. Consistent with this prediction, I find no evidence that JGTTRA affected the prices of firms in nontreaty countries. However, it is important to note that not finding a price reaction for nontreaty country firms is not conclusive evidence that there was no reaction; it does suggest, however, that if there was a reaction it was likely small.

This paper makes the following contributions. First, it contributes to our understanding of how investor-level taxes influence equity prices in a global capital market. As such, my findings complement the work of Desai and Dharmapala (2011) and Amiram and Frank (2016), who provide evidence about how portfolio holdings are affected by dividend tax capitalization in a global capital market. Given that the open-economy after-tax CAPM suggests portfolio holdings can change significantly as a response to dividend tax changes but prices may move only slightly (Desai and Dharmapala 2011; Amiram and Frank 2016), evidence that a change in one country’s dividend tax rate affects the portfolio holdings of foreign assets is not sufficient, by itself, to conclude that a significant price reaction occurred. Because of this, Amiram and Frank (2016) suggest that providing evidence of the effects of tax capitalization on equity prices in a global setting is an important avenue for future research. This study provides that evidence.

This paper also contributes to a large literature in economics that examines how U.S. policy choices spill over into other countries. For example, numerous papers find that U.S. monetary policy decisions are associated with changes in equity prices and macroeconomic variables in foreign countries (Ammer et al. 2010; Canova 2005; Wongswan 2009). I add to this literature by showing that U.S. fiscal policy decisions, in the form of tax cuts for U.S. investors, also have spillover effects.Footnote 1

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section 2 discusses prior literature and develops the hypotheses. Section 3 discusses my research design, and Section 4 presents sample selection and the results of my empirical tests. Section 5 concludes.

2 Hypothesis development

2.1 Global asset pricing literature review

Initially, asset pricing research focused on explaining prices in a domestic market (Sharpe 1964; Linter 1965). However, because financial markets have become increasingly global, a large literature also examines how equity prices are determined in a worldwide capital market. For example, Solnik (1977) and Grauer et al. (1976) show that the standard Sharpe-Lintner CAPM holds when replacing the domestic market portfolio with the world market (World CAPM). Other research examines whether the cross section of international equity returns is explained by risk factors that depend on size, the value of the firm, and momentum, in addition to a market factor (Fama and French 2012, 2017; Griffin 2002; Hou et al. 2011). The general finding from this literature is that the pricing of internationally traded assets depends on both local and global risk factors.

In addition to global and local risk factors, researchers have found other determinants of global equity prices. These determinants include exchange rate risk (De Santis and Gerard 1998; Vassalou 2000), monetary policy changes (Ammer et al. 2010; Canova 2005; Wongswan 2009), capital flows (Brennan and Cao 1997; Baker et al. 2012), and market segmentation (Foerster and Karolyi 1999; Sarkissian and Schill 2004). In this paper, I examine whether investor-level taxes affect global equity prices.

2.2 Investor-level taxes and asset prices literature review

2.2.1 Theoretical literature review

The theoretical literature examining how investor-level taxes affect equity prices has a long history. In a seminal paper, Miller and Modigliani (1961) show that dividend policy does not affect firm valuation in a perfect market with no taxes. Brennan (1970) extends their analysis by considering how investor-level taxes influence the valuation of the firm. Building on the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) of Linter (1965) and Sharpe (1964), Brennan (1970) shows that the expected or required risk premium on a given equity consists of a premium for how the security’s return covaries with the market return and a premium for expected dividend yield (often referred to as dividend tax capitalization (Sialm 2009) or the dividend tax penalty (Dhaliwal et al. 2003)).

Directly related to the analysis in this paper, Desai and Dharmapala (2011) build on the model from Brennan (1970) by analytically showing how JGTRRA will change the stock price of treaty country equities in an open-economy setting. (In Appendix 1, I discuss in more detail the framework and important assumptions underlying the open-economy after-tax CAPM. Appendix 1 also extends the original Desai and Dharmapala (2011) model to allow for covariance between the prices of treaty and nontreaty country stocks.)

Desai and Dharmapala (2011) show that when tax rates on dividends are higher than capital gains the equilibrium price of equity issued in treaty countries, P∗, will be:

where the first term,\( \frac{E\left[P\right]+\left(1-\overline{t}\right)D}{1+r} \), represents the discounted expected future cash flows, which are the expected equity price, E[P], plus the after tax dividend, \( \left(1-\overline{t}\right)D \), received at the end of the period.Footnote 2 Also, r is the return on the riskless asset, \( \overline{T} \) represents the demand for treaty country equities aggregated across all investors, and \( \overline{W} \) represents the aggregate wealth of investors. Most critical for the analysis in this paper, the tax rate, \( \overline{t} \), is the weighted average of dividend tax rates faced by the i investors within the market, where the weights are a function of their relative wealth levels invested in the market \( \left(\overline{t}=\frac{\Sigma_i{t}_i{W}_i}{\overline{W}}\right) \). Weighting the tax rates in this way ensures that large investors have a greater influence on equilibrium prices. Importantly, when calculating the weighted average tax rate, \( \overline{t} \), the weight of a particular investor’s tax rate depends on his or her wealth endowment and not their holdings of the particular asset. The second term in Equation (1), \( \frac{\gamma {\sigma}^2\overline{T}}{\left(1+r\right)\overline{W}} \), captures the impact on price of investors’ risk aversion (γ), with risk aversion being inversely proportional to wealth (\( \overline{W} \)).

Based on Equation (1), Desai and Dharmapala (2011) derive the effect of a reduction in the U.S. dividend tax rate (tUS) on the price of treaty country stock (P∗) as follows.Footnote 3

Equation (2) indicates that, when the U.S. dividend tax rate decreases, if the wealth of taxable U.S. investors is sufficiently large, relative to aggregate global wealth (\( \frac{W_{US}}{\overline{W}} \)), the weighted average tax rate for treaty firms will decrease, lowering dividend tax capitalization and increasing treaty country stock prices.Footnote 4,Footnote 5 However, if there is little U.S. wealth available to invest in non-U.S. firms or a large portion of the wealth is invested in tax-exempt investment vehicles, the change in the dividend tax rate may have no direct effect on the stock prices of treaty country firms. As the wealth of taxable U.S. investors, relative to global aggregate wealth, is important when predicting that JGTTRA will change treaty country stock prices, I address this topic in Section 2.4.Footnote 6

2.2.2 Empirical literature review

Empirical studies examining how investor-level taxes influence firm equity prices also have a long history and mostly investigate the question by looking at abnormal returns of U.S. equities, though a small international literature is beginning to develop.Footnote 7 None of these international papers, however, examine firm-level equity prices. For example, Desai and Dharmapala (2011) find that U.S. investors reallocate their foreign equity holdings toward treaty countries, following the 2003 dividend tax cut, consistent with the predictions of the open-economy after-tax CAPM. Jacob and Jacob (2013) use data covering two decades from 25 countries to show that a higher dividend tax penalty is associated with lower dividend payout. Amiram and Frank (2016) show that a country’s weighted-average tax rate on dividends paid to foreign and domestic investors is positively related to foreign portfolio investment. The intuition for their result is that a higher country average tax rate leads to lower stock prices, which entices foreign investors to increase their portfolio investment in that country. Because Desai and Dharmapala (2011) and Amiram and Frank (2016) argue that portfolio holdings can change without a corresponding change in equity prices, my paper complements theirs by examining short-window equity returns around a major U.S. dividend tax rate change to capture the impact of investor-level taxes on foreign asset prices.

2.3 How foreign stocks qualify for the reduced dividend tax rate

JGTTRA reduced the top dividend tax rate for U.S. individuals on all “qualified” dividend income. For a dividend to qualify, it had to be paid by a domestic corporation or a foreign qualified corporation. A foreign corporation is deemed to pay a qualified dividend if it meets one or more of three tests: the possession test, the securities market test, or the treaty test. A firm qualifies under the possession test if a foreign corporation is incorporated in a possession of the United States, such as Puerto Rico. Concerning the securities market test, a firm qualifies if it is trading on a U.S. securities market. This includes firms cross-listed on exchanges such as the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) or NASDAQ, in addition to those whose shares trade through American depositary receipts (ADRs). Firms traded on the OTC Bulletin Board or on the electronic pink sheets do not qualify for the lower dividend tax rate. (Internal Revenue Service 2003b). Because firms that meet the securities market test qualify for the lower tax rates on dividends paid to U.S. investors, I include these firms in my sample of treaty country firms. However, as cross-listed firms make up less than 5% of the sample, I focus the exposition of the paper on the treaty test, rather than the securities market test.

The third way a firm can qualify for a reduced dividend tax rate on dividends paid to U.S. investors is if that firm is “eligible for the benefits of a comprehensive income tax treaty with the United States which the Treasury Department determines to be satisfactory for purposes of this provision, and which includes an exchange of information program” (Internal Revenue Code 1(h)(11)(C)(i)(II) 2019). Treaty firms make up the main sample for my tests.

2.4 Hypotheses

JGTTRA provides a powerful setting to test whether dividend tax rate cuts in one country can lead to increases in equity prices in foreign countries, because it involves a significant reduction in the individual dividend tax rate for investors from the wealthiest country in the world (Credit Swiss Global Wealth Databook 2010). One of the main provisions of JGTRRA cut the top individual dividend tax rate from 38.6 to 15%, a 60% reduction. Referring to Equation (2), \( \frac{\partial {P}^{\ast }}{\partial {t}_{US}}=-\left(\frac{D}{1+r}\right)\left(\frac{W_{US}}{\overline{W}}\right) \), JGTTRA mandated a reduction of the U.S. dividend tax rate (tUS) for taxable individual U.S. investors. This should lead to a reduction in the weighted average tax rate for treaty country firms and an increase in treaty country equity prices (P∗) for higher dividend yield stocks. As a result, I make the formal hypothesis.

-

H1: There is a positive association between JGTTRA event window returns and firm dividend yield for firms in treaty countries.

The open-economy after-tax CAPM assumes assets are traded in an integrated global capital market. While this may be the case for equities of larger firms (nonmicrocaps), due to capital market frictions, it may not be the case for stocks of smaller firms (microcaps). Supporting the notion that market frictions exist for smaller stocks, Fama and French (2012) find that standard empirical asset-pricing models struggle to explain patterns in international stock returns for microcaps. Based on this, they conclude it is possible “integrated global pricing does not extend to microcaps” (p. 466). Further, smaller foreign stocks are less likely to be held by U.S. investors, which might mute any response to the dividend tax rate cut (Leuz et al. 2009; Ammer et al. 2012). For these reasons, I may find a larger reaction to the dividend tax rate cut for nonmicrocap firms. Based on these arguments, I make the following hypothesis.

-

H2: The positive association between JGTTRA event window returns and firm dividend yield will be stronger for nonmicrocap treaty country firms.

While I predict a positive association between abnormal returns and dividend yield, I may not find this result. This is because the theoretical analysis of Desai and Dharmapala (2011) shows that equity prices for treaty firms may not significantly increase if the ratio of total wealth of taxable U.S. investors is small, relative to global wealth, at the time of the dividend tax cut. Using available data, I can estimate this ratio and show it is potentially large enough for a stock price reaction to be observed. However, accurately calculating this ratio is challenging for at least two reasons: 1) from a practical perspective, it is unclear which components of U.S. investor wealth should be included in the ratio, and 2) even if the correct components of U.S. wealth are included in the ratio, it is not clear how much of it belongs to taxable investors.

To estimate this ratio, I begin by calculating the equities held by U.S. investors in treaty countries, nontreaty countries, and the United States. These seem to be the correct assets to incorporate based on the model in Desai and Dharampala (2011). Using the Treasury International Capital (TIC) reports on “U.S. Holdings of Foreign Securities as of December 31, 2001” and “Foreign Portfolio Holdings of U.S. Securities as of June 30, 2002,” I find that U.S. investors hold $17.9 trillion of treaty-country, nontreaty-country, and U.S. equities. Regarding aggregate global wealth, according to the Credit Swiss Global Wealth Databook (2010), at the end of 2002, worldwide wealth was $118.6 trillion. This means that over 15% of global aggregate wealth was held by U.S. investors in treaty-country, nontreaty-country, and U.S. equities. Regarding the proportion of wealth that would be taxable, Wolff (2010) shows that the wealthiest 10% of U.S. households, who are likely to be taxable and enjoy the benefits of the dividend tax cut, owned the vast majority of U.S. wealth.Footnote 8 Overall, because taxable U.S. investors likely held a nontrivial portion of aggregate global wealth, I predict there will be an increase in stock prices, as a result of the 2003 U.S. dividend tax cut, for higher dividend yield treaty firms.Footnote 9

In contrast to my prediction for treaty country equities, I do not anticipate JGTRRA will lead to a positive relation between abnormal returns and dividend yield for firms in nontreaty countries. As Desai and Dharmapala (2011) point out, the price of nontreaty country equities will be largely unaffected by JGTTRA, because the dividend tax rate did not change for U.S. investors receiving dividends from stocks in nontreaty countries. However, Desai and Dharmapala (2011) derive this result based on a model that assumes no covariance between the prices of treaty country and nontreaty country stocks. As a result, the changes in the expected returns of treaty country stocks do not affect the demand for (and hence the equilibrium price of) nontreaty country stocks. As previously mentioned, in Appendix 1, I extend the model in Desai and Dharmapala (2011) to allow for covariance between treaty and nontreaty country equity prices. In this case, the demand for nontreaty country stock depends on the expected returns of treaty country stocks, as the covariance between the two asset classes creates a hedging demand. Nonetheless, Appendix 1 shows that JGTRRA increases the price of treaty country stocks just enough to leave expected returns unchanged. As a result, demand for nontreaty country stocks remains constant and so does price (see equations (21) and (23).Footnote 10 Because the open-economy after-tax CAPM does not predict the tax rate cut will change prices for nontreaty country equities, regardless of whether prices are correlated, I hypothesize the following.

-

H3: There is a no association between JGTTRA event window returns and firm dividend yield for firms in nontreaty countries.

Because H3 predicts no effect, hypothesis testing cannot rule out the alternative of there being an effect. For that reason, I limit the inference to testing whether H3 is rejected in the data.

3 Research design

3.1 Event dates

All hypotheses are tested using stock returns from May 21–May 28, 2003. In prior research, Auerbach and Hassett (2007) constructed a list of eight important events leading up to the passage of JGTTRA, which they use to examine U.S. equity price reactions. For my research the important event window is the one when investors first became aware that the benefits of the dividend tax cut would be extended to dividends received from treaty country firms. To determine this, I searched the Congressional Record of the House and Senate for each day in the eight event windows identified by Auerbach and Hassett (2007). May 22, 2003, was the only day when the Congressional Record discussed extending the benefits of the tax cut to treaty countries but not to nontreaty countries. I also searched national and international business newspapers to see whether this distinction was mentioned prior to May 22, 2003, as it is possible that this feature of JGTRRA was being discussed in a more public forum. For each of the days during the eight events identified by Auerbach and Hassett (2007), I searched the Wall Street Journal and Financial Times, using the keywords “dividend,” “tax,” “Republican,” “Democrat,” “Bush,” “Congress,” “Senat” (for either senator or senate), “House,” and “cut.” I read each article flagged by the keyword searches for references but found no mention of the treaty versus nontreaty distinction before May 22, 2003. Hence I focus on this event window for my empirical tests. May 22, 2003 is the day before the Senate and House passed the bill that became law. In the work of Auerbach and Hassetts (2007), the event window May 21–28, 2003 contains five trading days, as the U.S. stock markets were closed on May 26 due to Memorial Day. As this holiday impacts the United States only, my event window contains six trading days over the same time period.

3.2 Event study methodology

3.2.1 Tests of H1 and H2

Because tax capitalization is expected to increase with dividend yield, I begin by examining the cumulative raw and abnormal returns of value-weighted portfolios based on dividend yield. Specifically, firms that paid dividends are sorted into quartiles based on dividend yield (defined as the ratio of dividends per share paid in 2002 to end of 2002 stock price).Footnote 11 Firms in the top quartile are defined as high-dividend. Firms in the bottom quartile are defined as low-dividend, while those in the middle two quartiles make up the medium-dividend group. I assign the firms that do not pay a dividend in 2002 to the low-dividend group.

To control for varying risk characteristics across portfolios, I assess stock performance using abnormal returns centered on the event date. These abnormal returns are calculated by first estimating beta using the CAPM, as follows.

I then calculate the abnormal return as the predicted errors, following Zhang (2007):

where ri, t is the value-weighted return for portfolio i on day t. The variable rF, t is defined as the risk-free rate of return on day t, rM, t is the value-weighted market return on day t, and \( {\beta}_{i,t}^M \) is the portfolio’s market beta, estimated using return data from calendar year 2002. The abnormal return (ARi, t) is calculated by subtracting portfolio i’s expected return on day t (\( \alpha +{\overline{\beta}}_{i,t}^M\left({r}_{M,t}-{r}_{F,t}\right) \)) from the realized return on day t (ri, t − rF, t). The abnormal returns for portfolio i are then cumulated over the event window to form the cumulative abnormal return (CARi). To test the significance of the raw and abnormal portfolio returns, I examine whether the event returns differ from the mean of all non-overlapping six-day portfolio returns from 2002.

The primary reason I use portfolios is because the event window perfectly overlaps in time for each firm in the sample, meaning there is likely contemporaneous correlation of returns across stocks. This affects how to correctly test the cumulative abnormal returns for statistical significance. Mandelker (1974) and Jaffe (1974) develop a simple way to overcome the problem. Their approach involves aggregating individual stock returns into portfolios and then carrying out the estimation of CARs at the portfolio level. This approach allows for cross-correlation of abnormal returns and generates appropriate standard errors.

In addition to the portfolio analysis, I test for a positive relation between CAR and dividend yield using multivariate regressions. While the value-weighted portfolios capture the impact of the U.S. dividend tax cut on the largest foreign firms, the multivariate regression allows each observation to have equal weight and estimates an on-average effect. Fama and French (2008) discuss how using both portfolio and multivariate methods provides more confidence in the results. The following regression is used to test H1.

where CAR is the cumulative abnormal return for firm i during the event window, estimated using the CAPM. Firm specific betas are calculated using return data from calendar year 2002. DividendYield is calculated as 2002 dividends per share divided by end of 2002 stock price for firm i and is the main variable of interest. I expect γ1will be positive and significant.

The regression also includes control variables. βSMB is an estimate of a firm’s sensitivity to the difference between the return on a portfolio of small and large stocks and is included because, over long periods, small firms tend to have higher abnormal returns (Fama and French 2012). βHML is an estimate of a firm’s sensitivity to the difference between the return on a portfolio of high book-to-market and low book-to-market stocks and is included because value firms have higher expected returns over long periods (Fama and French 2012). Both measures are calculated using a firm’s monthly returns from 2002 and monthly regional factors (i.e., Europe, Japan, Asia Pacific) from Ken French’s website.Footnote 12 Finally, all multivariate regressions include industry and country fixed effects. For detailed descriptions of how each variable is calculated, see Appendix 2.

To provide support for H2, I estimate Equation (5) separately for microcap and nonmicrocap treaty-country firms. In addition, I use the following regression to test for a significant difference between the stock price reaction of microcap and nonmicrocap stocks.

where NonMicrocap is equal to one if the firm is not a microcap and zero otherwise. All other variables are a defined in the same way as Equation (5). Following international asset pricing papers, such as Fama and French (2012) and Barber et al. (2013), among others, I use the NYSE breakpoints to determine which of the treaty country firms in my sample are microcaps. Specifically, firms with market values below the 20th percentile of NYSE firms are classified as microcaps. The determination of whether a firm is a microcap is made at the end of the month prior to the event window, April 2003, which leads to a breakpoint of $291 million (USD).Footnote 13 If the reaction is stronger for nonmicrocap firms, relative to microcap firms, I expect γ3will be positive and significant.

3.2.2 Test of H3

H3 predicts there will not be an association between JGTTRA event window abnormal returns and dividend yield for firms from nontreaty countries. H3 is tested using the following regression.

where CAR is calculated using the abnormal returns of firms from nontreaty countries and all other variables are defined in the same way as equation (5). I also examine whether the stock price reaction for firms in nontreaty countries is significantly less than in treaty countries using the following regression.

where NonTreaty is an indicator variable equal to one if the firm is headquartered in a nontreaty country and zero otherwise. Due to collinearity between NonTreaty and the country fixed effects, I do not include the main effect of NonTreaty in the regression. All other variables are defined in the same way as equation (5).

4 Results

4.1 Sample selection

To test H1 and H2, I obtain foreign stock returns, dividend yield, and market values from Compustat Global. I retain firms in the sample if they are headquartered in a country with a qualifying treaty or if they are cross-listed in the United States. I determine treaty countries based on Internal Revenue Service 2003a and identify qualifying cross-listed firms using BNY Mellon’s DR Directory for non-Canadian firms and CRSP for Canadian firms. Additionally, I require firms to have at least 200 nonmissing, nonzero daily returns in 2003.Footnote 14 This restriction ensures only liquid firms, where a reaction to new information can be observed, are kept in the sample. I also eliminate firms with a stock unit price less than one on any of the event dates to alleviate the low-priced stock problem, where small price movements can cause extreme returns (Zhang 2007). Finally, I require firms to have returns for each day in the event window to ensure a consistent sample of firms across the dates of interest.

Returns are calculated using the change in stock price in U.S. dollars from day t-1 to day t. Stock prices are converted into U.S. dollars using the daily exchange rate from the Compustat Global Exchange Rate Daily File. Using U.S. dollar-denominated returns is common in international studies (Fama and French 2012; Zhang 2007). The market capitalization of a firm on day t-1 is used to compute the weight of that firm’s return in the portfolio on day t. After applying these requirements, the sample contains 6722 unique treaty firms for the portfolio tests.

I construct samples for the multivariate regressions using the same data restrictions as the portfolio sample. In addition, I require data to calculate the control variables and to identify a firm’s industry. Finally, the dependent variable and all continuous independent variables are truncated at 1% and 99% to reduce the influence of outliers. There are 2254 nonmicrocap and 3639 microcap firms in the multivariate test of H1 and H2. To test H3, I impose the same data requirements as listed above. In addition, to be included in the sample for H3, the firm must be headquartered in a country that does not have a qualifying treaty with the United States, and the firm must not qualify for the lower dividend tax rate based on having a U.S. cross-listing. These data requirements result in 246 nonmicrocap and 510 microcap firms from nontreaty countries.

4.2 Descriptive statistics

Table 1 shows the number of firms from each treaty country included in the portfolio sample. Treaty countries not represented in the sample due to a lack of firms meeting data requirements include Egypt, Iceland, Jamaica, Kazakhstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Morocco, Romania, Slovak Republic, Trinidad and Tobago, Tunisia, and Ukraine. Consistent with prior literature, Table 1, Column 2, shows that firms from Canada, France, Germany, Japan, and the United Kingdom form a large proportion of the portfolio sample (Armstrong et al. 2010; Zhang 2007). Firms from these countries also make up over 60% of the aggregate market capitalization of the sample, as might be expected (Column 3). There are also a large number of firms from Korea (South), India, and China, but the combined market capitalization of these firms represents less than 6% of the sample. Table 1 also provides information about mean and median dividend yield (Column 4) and the percentage of firms paying dividends (Column 5) for each treaty country in the sample.

Table 2 shows descriptive statitistics for the sample of firms used in the porfolio and multivariate tests. Panel A provides mean and median 2002 dividend yield and end of year market value of equity in U.S. dollars for firms in each of the dividend-yield portfolios. Consistent with articles in the business press and findings in academic research, dividend yield is higher in foreign countries than in the the United States (Blitz et al. 2010; Hough 2012). For example, the median yield for firms in the high-dividend portfolio is 6.6%, whereas the median yield for the high-dividend portfolio of U.S. firms documented by Amromin et al. (2008) is 3.8%.

Panel B of Table 2 provides the estimated portfolio betas from equation (3). These betas are calculated by regressing the daily value-weighted portfolio return on either a daily value-weighted global market return (βGlobal) or Europe and Asia market return (βEuropeAsia). The global market return used for the portfolio test is the STOXX Global 1800 Index, while the Europe and Asia market return is the STOXX 1800 ex North America Index. Promotional material describes these indexes as providing a broad yet liquid representation of the world’s developed markets. The STOXX Global 1800 Index contains 600 American, 600 European and 600 Asia/Pacific stocks, while the STOXX 1800 ex North America Index only contains the 600 stocks from Europe and the 600 stocks from the Asia/Pacific region.Footnote 15 I use a broad market return for the portfolio tests because each portfolio contains firms from numerous countries. Prior research has also used indexes to proxy for broad market returns (Armstrong et al. 2010). The daily portfolio and market returns are reduced by the one month Treasury bill rate. (Following Fama and French 2012, this is my proxy for the risk-free rate of return.) Though informative, I view the results from the portfolio tests as descriptive, because of the uncertainty about whether I have identified the appropriate market returns to calculate the portfolio betas. In the multivariate analysis, I calculate firm-specific betas, using the firms’ local country market returns to overcome this concern.

Table 2, Panel C, shows descriptive statistics for treaty firms in the multivariate sample. The composition of this sample is similar to the composition of the portfolio sample, except there are no longer firms from Cyprus, Estonia, Russia, and Venezuela. As I will be examining the relation between abnormal returns and dividend yield for nonmicrocaps and microcaps separately, I also present the descriptive statistics separately. Consistent with prior research, Panel C shows that microcap firms tend to have more extreme returns than nonmicrocap firms (Fama and French 2008, 2012). Specifically, the mean CAR over the event windows was −0.1% for nonmicrocap firms and 1.1% for microcap firms. DividendYield is 2.5% and 2.2% for nonmicrocap and microcap firms, respectively.Footnote 16 As would be expected, there is a large difference between the means and medians of the Size variable. The mean (median) firm in the nonmicrocap sample has market value of equity (Size) of about $3.6 billion ($985 million), whereas the mean (median) firm in the microcap sample has market value of equity of $79 million ($51 million).

4.3 Main results

4.3.1 Results for H1 and H2

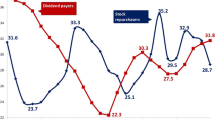

Table 3 documents the cumulative market return, raw portfolio returns, and portfolio CARs for the May 21–28, 2003 event window. The cumulative market return during the event window is large: 2.8% for the STOXX 1800 Global Index and nearly 2% for the STOXX 1800 ex North America Index. Also, the raw returns for all portfolios are large and significantly different than the 2002 mean return for the equivalent portfolio. Consistent with H1, the raw returns are monotically increasing with dividend yield. Specifically, the difference between the raw returns of the high- and low-dividend portfolios is 1.48%, which is significant (p value <0.05).Footnote 17 The difference between the high- and medium-dividend portfolios is also signficant (p value <0.05), but the difference between the medium- and low-dividend portfolios is not. Moving to the CARs, the return for the high-dividend portfolio, calculated using either the global market return (CARGlobal) or the Europe/Asia market return (CAREurope/Asia), is significantly larger than the 2002 mean CAR for the high-dividend portfolio (p value of <0.01) and economically large (0.79 and 1.24%, respectively). The 0.81 (1.04) percent difference between the high- and low-dividend portfolios for CARGlobal(CAREurope/Asia) is statistically significant with a p value <0.05 (<0.01). Similar to the results for the raw returns, the difference between the high- and medium-dividend portfolios is signficant (p value <0.01), but the difference between the medium- and low-dividend portfolios is not. As previously mentioned, while I view the results from the portfolio tests as descriptive, because of the challenge in identifying the appropriate market returns, these results suggest that firms in treaty countries experienced a reduction in tax capitalization around the time of the 2003 U.S. tax cut, consistent with H1.

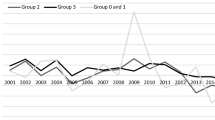

Table 4 presents the multivariate results when testing for a positive relation between abnormal returns and dividend yield for treaty country equities. Column 1 shows that, when both microcap and nonmicrocap firms are combined in the same sample, the coefficient on DividendYield is insignificant. Columns 2 and 3 report results when examining the nonmicrocap and microcap firms separately. In Column 2, the coefficient on DividendYield is 0.0767 with a p value of 0.031.Footnote 18 This suggests that there was a positive stock price reaction to the U.S. dividend tax rate cut for nonmicrocap firms in treaty countries. This coefficient indicates that, when moving from the 25th to 75th percentile of dividend yield, abnormal returns increased 0.22%. In contrast, the coefficient on DividendYield for microcap firms is negative and insignificant (coefficient − 0.0676, p value 0.938), suggesting that these firms did not benefit from the U.S. dividend tax rate cut (Column 3). This could be because integrated global pricing does not extend to microcaps, as suggested by the findings of Fama and French (2012). Column 4 reports the results of Equation (6), which estimates whether the reaction to the U.S. dividend tax rate cut was stronger for nonmicrocap firms. The positive and significant coefficient on DividendYield*NonMicrocap (0.1253, p value 0.013) suggests this was the case. Regarding the control variables, the coefficient on βSMB is postive and significant, consistent with longer window results in Fama and French (2012), and the coefficient on βHML is negative and significant. Overall, the portfolio results and multivariate results for nonmicrocap firms are consistent with the prediction that there will be a positive association between abnormal returns and dividend yield for firms in treaty countries around the passage of JGTTRA and that this reaction will be stronger for nonmicrocap firms.

4.3.2 Additional analysis for nonmicrocap firms

Table 5 contains the results of several robustness tests for the nonmicrocap firms. Table 5, Panel A, reports regression results after excluding foreign firms that are U.S. cross-listed. Blouin et al. (2009) show that, when the cost of cross-border arbitrage is low, home-country securities quickly mirror the pricing of their cross-listed counterparts, following a capital gains tax cut. However, the open-economy after-tax CAPM predicts a pricing reaction for a broader group of firms, so I exclude cross-listed firms to ensure they are not driving my results. As shown in Panel A, results are unchanged after dropping these firms, suggesting the results are driven by a broader price reaction than those documented by Blouin et al. (2009). Panel B of Table 5 shows results after excluding Japanese firms. I include this test because Japanese firms make up a large portion of my sample, and I want to ensure that one country is not for responsible for the results. As Panel B reports, dropping these firms does not change the results. In addition, I drop all observations from each country, one country at a time. Results remain significant at conventional levels for each regression when dropping one country at a time (untabulated). Overall, the results of these additional tests suggest that the U.S. dividend tax cut decreased the tax penalty for a broad group of firms in treaty countries.

4.3.3 Results for H3

H3 predicts there will not be an association between the JGTRRA event window returns and firm dividend yield for firms in nontreaty countries. Table 6 shows descriptive statistics for firms from nontreaty countries. The nontreaty sample includes firms from Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Hong Kong, Malaysia, Singapore, and Taiwan. Table 6 shows that the mean CAR over the event window was 0.7% and 1.7% for nonmicrocap and microcap firms, respectively. In untabulated results, I compare the CARs for the treaty country and nontreaty country samples. I find the mean CAR for the nonmicrocap firms in the nontreaty sample is significantly larger than the mean CAR for comparable firms in the treaty sample (Table 6 compared to Table 2 Panel C). All else equal, I would expect the average CAR for nonmicrocap treaty country stocks to be larger than the average CAR for nonmicrocap nontreaty country stocks. However, all else may not be equal, and there could be other international events affecting the mean CAR in nontreaty countries. To examine this possibility, I search for news about nontreaty countries in the Wall Street Journal and Financial Times from May 20, 2003, to May 28, 2003 (the day before the event window to the end of the event window). While I look for news about all the nontreaty countries, I am especially interested in news about Hong Kong and Taiwan, as they constitute over 80% of the observations and about 80% of the market capitalization of the nontreaty country sample.

I find evidence that the large abnormal returns for firms in nontreaty countries are likely due to events other than the U.S. dividend tax rate cut. Specifically, prior to my event window, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) caused the sickness of thousands and deaths of hundreds in Hong Kong and Taiwan (Dean and Richardson 2003). This led the World Health Organization to issue travel advisories for Hong Kong and Taiwan, which negatively impacted tourism (Melloan 2003). Further, the economies of these countries were also hurt because employees and consumers became cautious about leaving home for fear of catching the sickness (Buckman et al. 2003). However, during my event window good news about the abatement of SARS was announced, and I find that the large abnormal returns for the nontreaty sample are concentrated on days following this good news.Footnote 19

Table 7 shows multivariate results for H3. Panel A shows the relation between CAR and DividendYield for the sample containing only nontreaty firms. Columns 1 and 2 show that CAR and DividendYield are not significant related for either nonmicrocap or microcap nontreaty country firms. Panel B shows whether the relation between CAR and DividendYield is significantly less for nontreaty firms, relative to treaty firms. While I include the results for both nonmicrocap (Column 1) and microcap (Column 2) firms, I only expect the predicted relations to be present for nonmicrocap firms based on the results in Table 4. Column 1 shows that the association between CAR and DividendYield is significantly less for nonmicrocap firms in nontreaty countries, relative to nonmicrocap firms in treaty countries (coefficient − 0.1450, p value 0.078).

4.4 Alternative explanation

Next, I consider an alternative explanation for my findings. The results I document may not be due to a reduction in the dividend tax penalty but rather may be due to investors in foreign countries believing the dividend tax cut will improve the U.S. economy. Specifically, tax treaties could proxy for the connection between the U.S. and foreign economies, and dividend yield could proxy for firm-level sensitivity to the state of a country’s economy. This alternative explanation could explain why the sensitivity of abnormal returns to dividend yield is greater for treaty country firms.

I attempt to rule out this alternative explanation by examining proxies for the connectedness between the U.S. economy and the treaty countries in my sample. If the alternative explanation is correct, then the association between CAR and DividendYield should be stronger for firms in countries that have economies that are more connected to the U.S. economy. However, if the results are due to a decrease in tax capitalization, as predicted by the open-economy after-tax CAPM, I would not expect proxies of economic connectedness to explain abnormal stock returns for firms in treaty countries. An intuitive indicator of the connectedness of a foreign economy to the U.S. economy is the percentage of exports the foreign country sends to the U.S. Research shows that imports increase when real spending increases (Clarida 1994, 1996) and decrease when income decreases (Romer and Romer 2010). As the dividend tax cut was expected to increase after-tax income in the United States (Snow 2003), the tax cut could reasonably have led to an increase in demand for imported goods, with countries that export the most to the United States benefiting the most. Therefore I examine whether countries that import more into the United States have a larger reaction to the dividend tax rate cut than those that import less. To test this prediction, I use the following equation.

where HighImport is a proxy capturing a country’s economic connectedness to the U.S. economy and all other variables are as previously defined. I measure HighImport in two ways. First, HighImport is a variable equal to one if the country belongs to NAFTA (Canada and Mexico) and zero otherwise. According to data from the World Bank in 2002, over 85% of Canadian and Mexican exports were imported into the United States, the highest percentages of all the treaty countries in my sample. Therefore these countries likely would benefit most from an improvement in the U.S. economy. Second, I measure HighImport using country-specific import data obtained from the World Bank (http://data.worldbank.org/data-catalog/wits). I rank countries represented in my treaty sample based on their imports into the United States as a percentage of their worldwide exports (import percentage). I code HighImport as an indicator variable equal to one for firms from the countries that make up the top 25% of my observations based on import percentage and zero otherwise. This variable codes firms from Canada, Mexico, Israel, and Japan as HighImport. Due to collinearity between HighImport and the country fixed effects, I do not include the main effect of HighImport in the regression. If connectedness explains my results, then γ3 should be positive and significant. However, based on the predictions from the after-tax open-economy CAPM, I expect γ3 will be insignificant.

Table 8 shows the results when estimating equation (9). I only examine nonmicrocap firms, as they are the firms where the results supporting dividend tax capitalization are found. Column 1 shows the results when HighImport proxies for a NAFTA country, and Column 2 shows the results when HighImport proxies for a country that is in the top quartile of importers into the United States. The coefficient on γ3 is not significant in either columns 1 or 2, inconsistent with the alternative story.

5 Conclusion

I test whether there is a positive association between abnormal returns and dividend yield for firms in treaty countries around the enactment of JGTRRA. This test is motivated by predictions from the open-economy after-tax CAPM, which shows that the tax penalty capitalized into a firm’s expected return is a function of the difference between the average dividend and capital gain tax rates of all market participants (Desai and Dharamapala 2011). In today’s world of globally integrated capital markets, this means the dividend tax penalty is determined using “a global average of investor tax rates (Desai and Dharmapala 2011, p. 271).” Based on these models, I predict that a large dividend tax cut in the United States will lower the tax penalty for high-dividend yield firms in treaty countries.

Using both portfolio analysis and multivariate regressions, I document a significantly positive relation between abnormal returns and dividend yield for treaty country firms around the U.S. dividend tax cut. For the tests using multivariate regressions I document that the positive relation is only present for nonmicrocap firms. I also find no signficant relation between abnormal returns and dividend yield for equities in nontreaty countries around the dividend tax cut. Collectively, the results provide evidence that there was a reduction in dividend tax capitalization due to the 2003 U.S. dividend tax cut. Overall, this paper provides evidence that, under certain conditions, dividend tax changes in one country can effect the equity prices of firms in other countries. This finding increases understanding of how global equilibrium equity prices are formed in a world where capital markets continue to integrate.

Notes

Research in this area primarily uses announcements by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) to capture changes in U.S. monetary policy. The two FOMC announcements closest to the event window used in this paper are May 6, 2003, and June 25, 2003, making it unlikely I am picking up any effects from announcements about U.S. monetary policy (Gurkaynak et al. 2005).

Desai and Dharmapala (2011) assume the tax rate on capital gains is zero, which is why the expected equity price, E[PT], is not reduced by taxes. This is not an unreasonable assumption, as Constantinides (1984) and Dammon et al. (2001) show that investors can reduce or eliminate capital gains taxes by accelerating the realization of capital losses and deferring the realization of capital gains. Empirically, Sialm (2009) shows that capital gains yields are relatively small, and Sialm and Starks (2012) document that the highest capital gains yields are realized by investors who will not pay current tax on the realizations (because the assets are held in tax-qualified retirement accounts).

The tax rate is the same for U.S. investors on U.S. and treaty country equities. Therefore the implications of the dividend tax rate cut for treaty country stocks will also apply to U.S. equities.

Until fairly recently, predictions about tax capitalization in the accounting literature were based on the logic of the marginal investor approach. Under the marginal investor approach, it is the marginal investor’s tax rate that determines the dividend tax premium (Ayers et al. 2002; Dhaliwal et al. 2003; Dhaliwal et al. 2007), rather than the weighted average tax rate. Guenther and Sansing (2010) correctly assert that the marginal investor approach is inconsistent with equilibrium pricing for a market with risky assets, which is why I motivate the hypotheses in this paper using the open-economy after-tax CAPM from Desai and Dharmapala (2011).

The tax rate change is assumed to apply only to the near term dividend, D, which implies the expected equity price, E[P], is unaffected.

For research about the relation between investor-level taxes and U.S. equities see Litzenberger and Ramaswamy (1979), (1980), Gordon and Bradford (1980), Miller and Scholes (1982), Naranjo et al. (1998), Dhaliwal et al. (2003), Dhaliwal et al. (2005), Sialm (2009), Auerbach and Hassett (2007) and Amromin et al. (2008).

Specifically, Wolff (2010) shows that, as a percentage of total wealth owned by U.S. households in 2001, the top 10% owned 85% of outstanding stocks. Given this finding, it seems likely that the wealthiest 10% of U.S. households, who owned a large portion of U.S. equities and by extension global wealth, were taxable U.S. investors. Importantly, the U.S. data in the Credit Swiss Global Wealth Databook (2010) and the data in Wolff (2010) both come from the U.S. Survey of Consumer Finance. In addition, individual net worth is defined in a similar way in both the Credit Swiss Global Wealth Databook (2010) and Wolff (2010), making comparisons between the studies appropriate.

There is variation in how much equity is held by U.S. investors in treaty countries. For example, based on 2003 holdings, U.S. investors owned 17% of equities in the United Kingdom but only 6% of the equities in Italy.

Another important assumption is that the dividend flow is certain. If the dividend flow is not certain, then the dividend tax rate change would affect the variances and covariances of the cash flows, and H3 may not hold. Nonetheless, prior literature suggests the assumption that dividend flow is certain is reasonable. For example, Linter (1956), DeAngelo et al. (2004), and Denis and Osobov (2008) show that dividends paid by firms in the United States and other large economies are sticky, so any variance effects are likely to be second order. Also, based on the observation that dividends tend to be sticky, researchers typically measure future dividends based on past dividends (Dhaliwal et al. 2007; Sialm 2009; Sialm and Starks 2012).

Desai and Dharmapala (2011) model the equilibrium price as a function of dividends paid (DT). In my empirical specifications, I essentially transform equation (1) into a model of expected returns, similar to the original model developed by Brennan (1970), and examine the relation between stock returns and dividend yields.

Ideally I would include SMB and HML adjustments in my calculation of CAR, but unfortunately I cannot obtain daily SMB and HML factors for all of the countries in my sample. However, Ken French does provide regional monthly factors on his website. (The construction of these factors is detailed in Fama and French 2012.) I use these monthly factors to calculate each firm’s factor risk loadings for the regional SMB and HML factors and include these loadings as controls (βSMB and βHML, which are defined in Appendix 2). Other papers that have included a firm’s factor risk loading/historical sensitivity to the SMB and HML factors as control variables include Dhaliwal et al. (2007) and Konchitchki et al. (2016).

I thank Ken French for providing this information on his website http://mba.tuck.dartmouth.edu/pages/faculty/ ken.french/data_library.html (accessed March 22, 2018).

Returns for Canadian listed firms are not available in Compustat Global or CRSP, so I obtain returns for these firms from DataStream.

More detail about the STOXX 1800 index can be obtained at https://www.stoxx.com/index-details?symbol=SXW1GR (accessed March 22, 2018).

Because dividend yield is, on average, positive for treaty country firms, Equation (2) suggests the mean CAR for the event window will be positive. One reason this may not be the case is transaction costs. Specifically, if transaction costs in treaty countries are large enough, the benefit of investing in the firm with the average dividend yield may not outweigh the cost, leading to a small amount of investment. However, as a stock’s dividend yield increases, the benefit of investing in that stock outweighs the cost of making the investment, which could lead the stock to experience abnormal returns. If this is a plausible explanation, I would expect the unconditional mean abnormal return for treaty country stocks to become positive for stocks above a certain level of dividend yield (which is when the benefits of investing outweigh the transaction costs). This is different than the main prediction in my paper, which predicts a positive association between CAR and dividend yield, because this association could exist, even if all returns for treaty country stocks are negative. I find that for firms with a dividend yield above the 75th percentile the mean CAR is positive (untabulated). Also, using data from Domowitz et al. (2001), Table 1, which contains the one-way cost of an equity transaction for most of the treaty countries, I estimate the weighted transaction cost for firms in my sample is 48.27 basis points, where the weight is determined using the number of observations from a country. Considering the size of the returns I document in Tables 3 and 4, the weighted transaction cost of 48.27 basis points is fairly large, suggesting transactions costs are likely to be a salient component of investment decisions, especially for lower dividend yield stocks. Thus transaction costs could partially explain why the mean CAR for treaty country stocks is not positive.

Examining raw returns for the portfolio tests is important, because firms included in the STOXX 1800 Indexes may be effected by the dividend tax rate cut. If this is the case, then removing the market effect from the raw portfolio return to calculate the abnormal return could be discarding some of the effect I am testing for; hence the importance of examining both the raw and abnormal return.

I find a similar result if I calculate cumulative abnormal returns by adjusting the firm return by the local market return, rather than using the market model. This result is also unchanged if I use local currency, rather than U.S. dollar-denominated returns, cluster the standard errors by country or industry, calculate firm specific betas using global rather than local market returns, and if I do not truncate the dependent variable (untabulated).

Important good news occurred on Friday May 23, 2003, when the World Health Organization lifted its travel advisory for Hong Kong (Dean and Richardson 2003). This travel advisory was lifted after the markets closed on Friday (Sanchanta 2003). Further, on Monday May 26, 2003, a Wall Street Journal article stated that, due to only a few new cases of SARS being reported, “Taiwan’s SARS outbreak showed further signs of stabilizing” (Dean and Richardson 2003). I examine mean daily abnormal returns for my sample of nonmicrocap, nontreaty stocks and find that the majority (0.0056) of the mean CAR reported in Table 6 (0.007) occurred on May 26, 2003, consistent with the large CAR being related to good news about the abatement of SARS.

Assuming dividends are deterministic is important for the following reason. As shown in Sikes and Verrecchia (2012), an investor-level tax cut will have two effects on equity prices. First, the tax cut will increase expected after-tax cash available for investors (the payoff effect). An increase in expected after-tax cash drives up share prices and decreases expected pre-tax rates of return. “However, in a diversified market setting along the lines of the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM), [a decrease in investor-level tax rates] also [increases] risk because the tax authority absorbs [less] of the risk associated with firms’ residual cash flows (variance of the payoff effect). When risk [increases], share prices [decrease] and, thus, expected pre-tax rates of return [increase]” (Sikes and Verrecchia 2012, p. 1068). Thus the payoff effect and the variance of the payoff effect could offset each other. However, assuming dividends are deterministic ensures the expected payoff effect of a dividend tax rate change will dominate any effects to the variance of the payout.

The assumption that the risk aversion parameter (γ) is deflated by wealth (W) serves two purposes in the model. First, it permits a parsimonious representation of demand and prices within the context of the model. Second, and more importantly, it allows the model to have a notion of size and therefore captures the equilibrium pricing influence of an affected investor class (e.g., U.S.). The notion of size is reflected by the exogenous wealth of the investors and introduces tension to the story, because, if there is little U.S. wealth available to invest in non-U.S. firms, there will be no direct effect of changes in the dividend tax on non-U.S. equity prices.

An important assumption of the model is that the dividend tax rate cut is not permanent and only applies to the next dividend. If this assumption was not made, I shouldn’t see different stock price reactions for firms that are currently paying high dividends verses firms that are currently paying low dividends, because the effect of the dividend tax rate cut on share price should be independent of when the dividends are paid. Importantly, this assumption fits the expectations investors had about the permanence of JGTTRA. Specifically, the tax rate decrease for dividends was originally set to expire on December 31, 2008. However, it has been extended several times and finally rose to 20% for individuals making more than $400,000 in 2013. The expectation that the dividend tax rate would rise in the future is important, as it means the timing of dividend payments matters and suggests firms with high dividend payouts would have greater increases in stock price.

References

Amiram, D., & Frank, M. M. (2016). Foreign portfolio investment and shareholder dividend taxes. The Accounting Review, 91, 717–740.

Ammer, J., Vega, C., & Wongswan, J. (2010). International Transmission of U.S. Monetary Policy Shocks: Evidence from Stock Prices. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 42(Supplement 1), 179–198.

Ammer, J., Holland, S., Smith, D., & Warnock, F. (2012). U.S. international equity investment. Journal of Accounting Research, 50, 179–198.

Amromin, G., Harrison, P., & Sharpe, S. (2008). How did the 2003 dividend tax cut affect stock prices? Financial Management, 625–646.

Armstrong, C., Barth, M. E., Jagolinzer, A. D., & Riedl, E. J. (2010). Market reaction to the adoption of IFRS in Europe. The Accounting Review, 85, 31–61.

Auerbach, A. J., & Hassett, K. A. (2007). The 2003 dividend tax auts and the value of the firm: an event study. In A. Auerbach, J. Hines, & J. Slemrod (Eds.), Taxing Corporate Income in the 21st Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ayers, B. C., Cloyd, C. B., & Robinson, J. R. (2002). The Effect of Shareholder-Level Dividend Taxes on Stock Prices: Evidence from the Revenue Reconciliation Act of 1993. The Accounting Review, 77, 933–947.

Baker, M., Wurgler, J., & Yuan, Y. (2012). Global, local, and contagious investor sentiment. Journal of Financial Economics, 104, 272–287.

Barber, B. M., De George, E. T., Lehavy, R., & Trueman, B. (2013). The earnings announcement premium around the globe. Journal of Financial Economics, 108, 118–138.

Blitz, D., Huij, J., & Swinkels, J. (2010). The performance of European index funds and exchange-traded funds. European Financial Management, 18, 649–662.

Blouin, J., Hail, L., & Yetman, M. H. (2009). Capital gains taxes, pricing spreads, and arbitrage: Evidence from cross-listed firms in the U.S. The Accounting Review, 84, 1321–1361.

Brennan, M. J. (1970). Taxes, market valuation and corporate financial policy. National Tax Journal, XXIII, 417–428.

Brennan, M. J., & Cao, H. H. (1997). International Portfolio Investment Flows. Journal of Finance, 52, 1851–1880.

Buckman, R., Wain, B., & Crispin, S. (2003). Asia Now Dares To Make Plans For After SARS—Ministers, CEOs, Cabbies Warily Prepare to Carry On; Shock of a Packed Ribs Joint. Wall Street Journal, A.11.

Canova, F. (2005). The Transmission Of US Shocks To Latin America. Journal of Applied Econometrics, 20, 229–251.

Clarida, R. H. (1994). Cointegration, aggregate consumption, and the demand for imports: A structural econometric investigation. American Economic Review, 84, 298–308.

Clarida, R. H. (1996). Consumption, import prices, and the demand for imported consumer durables: A structural econometric investigation. Review of Economics and Statistics, 78, 369–374.

Constantinides, G. (1984). Optimal stock trading with personal taxes: Implications for prices and the abnormal January returns. Journal of Financial Economics, 13, 65–89.

Credit Suisse, Global Wealth Databook. (2010). Available at: https://www.credit-suisse.com/corporate/en/research/research-institute/global-wealth-report.html. Accessed 07 Mar 2019.

Dammon, R., Spatt, C., & Zhang, H. (2001). Optimal Consumption and Investment with Capital Gains Taxes. Review of Financial Studies, 14, 583–616.

De Santis, G., & Gerard, B. (1998). How big is the premium for currency risk? Journal of Financial Economics, 49, 375–412.

Dean, J, & Richardson, K. (2003). The SARS Outbreak: SARS Situation Eases in Asia’s Hard-Hit Spots. Wall Street Journal. D.8.

DeAngelo, H., DeAngelo, L., & Skinner, D. (2004). Are dividends disappearing? Dividend concentration and the consolidation of earnings? Journal of Financial Economics, 72, 425–456.

Desai, M. A., & Dharmapala, D. (2011). Dividend taxes and international portfolio choice. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 93, 266–284.

Denis, D., & Osobov, I. (2008). Why do firms pay dividends? International evidence on the determinants of dividend policy. Journal of Financial Economics, 89, 62–82.

Dhaliwal, D., Krull, L., Li, O. Z., & Moser, W. (2005). Dividend taxes and implied cost of equity capital. Journal of Accounting Research, 43, 675–708.

Dhaliwal, D., Krull, L., & Li, O. Z. (2007). Did the 2003 Tax Act reduce the cost of equity capital? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 43, 121–150.

Dhaliwal, D., Li, O. Z., & Trezevant, R. (2003). Is a dividend tax penalty incorporated into the return on a firm’s common stock? Journal of Accounting and Economics, 35, 155–178.

Domowitz, I., Glen, J., & Madhavan, A. (2001). Liquidity,Volatility and Equity Trading Costs Across Countries and Over Time. International Finance, 4, 221–255.

Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (2008). Dissecting anomalies. Journal of Finance, 63, 1653–1678.

Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (2012). Size, value, and momentum in international stock returns. Journal of Financial Economics, 105, 457–472.

Fama, E. F., & French, K. R. (2017). International tests of a five-factor asset pricing model. Journal of Financial Economics, 123, 441–463.

Foerster, S. R., & Karolyi, G. A. (1999). The Effects of Market Segmentation and Investor Recognition on Asset Prices: Evidence from Foreign Stocks Listing in the United States. Journal of Finance, 54, 981–1013.

Gordon, R. H., & Bradford, D. F. (1980). Taxation and the stock market valuation of capital gains and dividends. Journal of Public Economics, 14, 109–136.

Grauer, F. L. A., Litzenberger, R. H., & Stehle, R. E. (1976). Sharing rules and equilibrium in an international capital market under uncertainty. Journal of Financial Economics, 3, 233–256.

Griffin, J. M. (2002). Are the Fama and French factors global or country specific? Review of Financial Studies, 15, 783–803.

Guenther, D. A., & Sansing, R. (2010). The effect of tax-exempt investors and risk on stock ownership and expected returns. The Accounting Review, 85, 849–875.

Gurkaynak, R., Sack, B., & Swanson, E. (2005). The Sensitivity of Long-Term Interest Rates to Economic News: Evidence and Implications for Macroeconomic Models. The American Economic Review, 95, 425–436.

Hou, K., Karolyi, G. A., & Kho, B. C. (2011). What factors drive global stock returns? Review of Financial Studies, 24, 2527–2574.

Hough, J. (2012). For better dividend opportunities, look overseas. Wall Street Journal. Available at: http://www.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052702303296604577452850482206134.

Internal Revenue Code (2019). Tax Imposed. Section 1(h)(11)(C)(i)(II). Available at: https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/26/1. Accessed 07 Mar 2019.

Internal Revenue Service. (2003a). United States Income Tax Treaties That Meet the Requirements of Section 1(h)(11)(C)(i)(II). Notice 2003-69. Available at: https://www.irs.gov/irb/2003-42_IRB/ar09.html. Accessed 07 Mar 2019.

Internal Revenue Service. (2003b). Stock That is Considered Readily Tradable on an Established Securities Market in the United States for Purposes of Section 1(h)(11)(C)(ii). Notice 2003-71. Available at: https://www.irs.gov/irb/2003-43_IRB/ar10.html. Accessed 07 Mar 2019.

Jacob, M., & Jacob, M. (2013). Taxation, Dividends, and Share Repurchases: Taking Evidence Global. Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis, 48, 1241–1269.

Jaffe, J. F. (1974). Special information and insider trading. The Journal of Business, 47, 410–428.

Karolyi, G., & Stulz, R. (2003). Are financial assets priced locally or globally? In G. Constantinides, R. Stulz, & M. Harris (Eds.), Handbook of the economics of finance (pp. 975–1020). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Konchitchki, Y., Luo, Y., Ma, M. L. Z., & Wu, F. (2016). Accounting-based Downside Risk, Cost of Capital, and the Macroeconomy. Review of Accounting Studies, 21(1), 1–36.

Leuz, C., Lins, K., & Warnock, F. (2009). Do Foreigners Invest Less in Poorly Governed Firms? Review of Financial Studies, 22, 3245–3285.

Linter, J. (1956). Distribution of incomes of corporations among dividends, retained earnings, and taxes. American Economic Review, 46, 97–113.

Linter, J. (1965). The valuation of risk assets and the selection of risky investments in stock portfolios and capital budgets. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 47, 13–37.

Litzenberger, R., & Ramaswamy, K. (1979). The effect of personal taxes and dividends on capital asset prices: theory and Empirical Evidence. Journal of Financial Economics, 7, 163–195.

Litzenberger, R., & Ramaswamy, K. (1980). Dividends, Short Selling Restrictions, Tax-Induced Investor Clienteles and Market Equilibrium. Journal of Finance, 35, 469–482.

Mandelker, G. (1974). Risk and return: The case of merging firms. Journal of Financial Economics, 1, 303–335.

Melloan, G. (2003). Deflation Is Only a Symptom of a Global Malaise. Wall Street Journal. A.19.

Miller, M. H., & Modigliani, F. (1961). Dividend policy, growth, and the valuation of shares. The Journal of Business, 34, 411–433.

Miller, M. H., & Scholes, M. S. (1982). Dividends and taxes : Some empirical evidence. Journal of Political Economy, 90, 1118–1141.

Naranjo, A., Nimalendran, M., & Ryngaert, M. (1998). Stock returns, dividend yields, and taxes. Journal of Finance, 53, 2029–2057.

Romer, C. D., & Romer, D. H. (2010). The macroeconomic effects of tax changes: Estimates based on a new measure of fiscal shocks. American Economic Review, 100, 763–801.

Sanchanta, M. (2003). Bank rally and upbeat Sars news lifts region. Financial Times, 42.

Sarkissian, S., & Schill, M. J. (2004). The Overseas Listing Decision: New Evidence of Proximity Preference. Review of Financial Studies, 17, 769–809.

Sharpe, W. F. (1964). Capital asset prices: A theory of market equilibrium under conditions of risk. Journal of Finance, 19, 425–442.

Sialm, C. (2009). Tax changes and asset pricing. The American Economic Review, 99, 1356–1383.

Sialm, C., & Starks, L. (2012). Mutual fund tax clienteles. Journal of Finance, 67, 1397–1422.

Sikes, S., & Verrecchia, R. E. (2012). Capital gain taxes and expected rates of return. The Accounting Review, 87, 1067–1086.

Snow, J. (2003). United States Treasury Secretary’s statement to the House Ways and Means Committee.

Solnik, B. H. (1977). Testing international asset pricing: Some pessimistic views. Journal of Finance, 32, 503–512.

Vassalou, M. (2000). Exchange rate and foreign inflation risk premiums in global equity returns. Journal of International Money and Finance, 19, 433–470.

Wolff, E. (2010). Recent trends in household wealth in the United States: rising debt and the middle-class squeeze—an update to 2007. Unpublished Paper No. 589. Levy Economics Institute of Bard College, 2010. Available at: http://www.levyinstitute.org/publications/recent-trends-in-household-wealth-in-the-united-states-rising-debt-and-the-middle-class-squeezean-update-to-2007. Accessed 07 Mar 2019.

Wongswan, J. (2009). The response of global equity indexes to U.S. monetary policy announcements. Journal of International Money and Finance, 28, 344–365.

Zhang, I. X. (2007). Economic consequences of the Sarbanes–Oxley Act of 2002. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 44, 74–115.

Acknowledgements

This paper is based on my dissertation at the University of Arizona. I express gratitude for the support and guidance of my dissertation committee: Dan Dhaliwal (chair), Christopher Lamoureux (finance), and Kirsten Cook. This paper has also benefited from the comments and suggestions of two anonymous reviewers, Jenny Brown, Andrew Call, Dane Christensen, Paul Fischer (the editor), Curtis Hall, Phillip Lamoreaux, Michal Matejka, Landon Mauler, Shyam V. Sunder, Roger White, and particularly Pablo Casas Arce as well as workshop participants at the 2012 BYU Accounting Symposium, Arizona State University, George Mason University, The University of Iowa, University of Arizona, University of British Columbia, University of Missouri – Columbia, and University of Waterloo. I also thank Jim Seida (discussant) and participants at the 2013 Journal of the American Tax Association Midyear Meeting.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Open Ecomony After-Tax CAPM

In this appendix, I extend the open-economy after-tax CAPM derived by Desai and Dharmapala (2011). One of the assumptions of their model is that there is no covariance between the prices of treaty and nontreaty stocks. Because this assumption may affect the equilibrium prices of both types of stocks, I extend their model to allow for covariance. In this appendix, I use detailed notation. However, I drop the subscripts in the equations in the main body of the text to avoid excessive notation.

I use the same model set up as Desai and Dharmapala (2011). Specifically, I assume a world with a large number of investors with aggregate wealth \( \overline{W} \). Each country i has a representative investor, who has wealth endowment Wi. There are three investment opportunities: a riskless bond (B) and two risky assets in the form of equity issued in treaty countries (T) and equity issued in nontreaty countries (N). There are two periods. Investors allocate their wealth between bonds (where the yield is equal to r and the price is normalized to 1) and treaty and nontreaty country stocks, which have beginning prices denoted by pT and pN, respectively. The equity earns returns in the form of price appreciation and deterministic dividends (DT for treaty country equity and DN for nontreaty country equity).Footnote 20 The second-period equity prices, PT and PN, are a realization of a stochastic variable with mean E[PT] and E[PN] and variance \( {\sigma}_T^2 \) and \( {\sigma}_N^2 \), respectively. (Random variables are denoted using bold letters.)

In period 1, the representative investor of country i allocates her wealth among the bonds and treaty and nontreaty equities. The investor’s holdings of bonds (Bi) are determined residually, via the wealth constraint, after she chooses her holdings of treaty equity (Ti) and nontreaty equity (Ni):

These choices are assumed to maximize the following mean-variance utility function:

where Zi is a random variable denoting the representative investor’s wealth at the end of the second period and γ is a risk-aversion parameter. The utility function assumes an investor’s risk aversion is inversely proportional to her wealth.Footnote 21 It is assumed all investors have utility functions of this form. E[Zi] can be expressed as:

where tT, i is the tax rate on treaty country dividends received by the representative investor and where tN, i is the tax rate on nontreaty country dividends received by the representative investor. Further, allowing for treaty and nontreaty stocks to covary, I calculate Var[Zi] as:

where σTN is the second-period expected covariance between PT and PN. I can now substitute the expected wealth and its variance into the investor’s utility function. The optimal asset allocation satisfies the following first-order conditions for treaty country equities.

and nontreaty country equities:

Solving for the system of equations, I find that the representative investor of country i will have optimal holdings of treaty country stock (\( {T}_i^{\ast } \)) equal to:

and optimal holdings of nontreaty stock (\( {N}_i^{\ast } \)) equal to: