Abstract

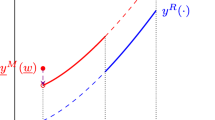

The Laffer curve is often used to analyze revenue-maximizing tax pressure and to provide normative suggestions to policymakers. We suggest that although the Laffer curve provides valuable insights, revenue maximization is not the only factor guiding policymakers’ decisions in regard to the suitable tax pressure. Thus, we try to broaden the spectrum by replacing the Laffer curve with a different graphical instrument, which takes into account three key variables: the quality of public expenditure, ideology (the role of populism) and rent-seeking. By means of this new graphical instrument, we derive results that shed light on the nature of the equilibria various countries can hope to obtain, as well as on the features of the imbalances. We then extend our insights to an open-economy contest featuring tax competition. In particular, we assess when tax competition is relevant, and we investigate whether the proposed remedy–tax harmonization–is credible. It is argued that tax harmonization is inferior to cooperation and that it is in fact an intermediate step on the way towards tax centralization.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As the text makes clear, the “suitable” tax pressure differs from the “optimal” tax pressure mentioned in the literature, according to which “a tax system should be chosen to maximize a social welfare function subject to a set of constraints” (Mankiw et al. 2009: 148).

Both elasticities are calculated with respect to the marginal tax pressure.

The presence of a bell-shaped curve describing tax revenues as a function of tax pressure had already been suggested by Smith (1981/1776: V.ii.k.33), it was clearly spelled out in Dupuit (1844) and was regularly used in political debates as early as 1848. See, however, Théret and Uri (1988) for an early survey of the critiques against the theoretical foundations of this literature.

Although one might argue that redistribution is actually a form of rent-seeking, in this paper redistribution refers to transfers of wealth–say, by means of tax breaks, subsidies, and free supply of merit goods—from one group of individuals to another, according to a general principle of income or wealth equalization (social solidarity or capability, as put forward in Sen 1999). By contrast, we refer to rent-seeking when wealth transfers are discretionary privileges granted to selected interest groups, regardless of the general principle of social solidarity.

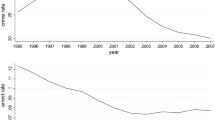

I am grateful to a referee of this Review for having pointed out the role of tax evasion, a phenomenon that manifestly gathers speed as tax pressure increases. The role of tax evasion can be split into two components. The first component is the taxable-income effect. Since the propensity to avoid taxes rises with tax pressure, for each level of economic activity, taxable income is a negative function of tax pressure. As a result, when tax pressure is low, an increase in tax pressure t leads to an increase in tax revenues despite the revenue losses created by tax evasion; by contrast, when tax pressure is high, an increase in tax pressure leads to a decrease in tax revenues. The second component relates to efficiency. Tax evasion is more likely to go undetected in small and medium size enterprises, than in large companies. Hence, firms tend to be relatively small in environments characterized by significant tax avoidance. In this light, high tax pressure hurts efficiency, and the distortion is larger, the greater the incentive to evade taxation.

To summarize, tax evasion makes the feasible range flatter and the prohibitive range steeper (the taxable income effect); and moves the top of the curve to the left (the inefficiency effect). Yet, we observe that the essence of the Laffer-curve and its inverted-U shape remain largely unaltered. This explains why, for the sake of simplicity, this article does not take tax evasion into account.

Feige and McGee (1983), Buchanan and Lee (1984), and Olson (1982) emphasized that taxation discourages investment and feeds a correspondingly large public expenditure that frequently translates into inefficiencies. See also Bergh and Henrekson (2011) and Salotti and Trecroci (2012) for more recent contributions.

The choice of T C is explained in the following paragraphs.

T C is shorter than T L , the long time horizon associated to no rent-seeking.

This assumption will be partially relaxed in the next section.

See also Smith (1981/1776: V.ii.f.10), who observed that tax compliance is higher “where the people have entire confidence in their magistrates, are convinced of the necessity of the tax for the support of the state, and believe that it will be faithfully applied to that purpose”.

For example, either the policymakers prevailing under pop 1 have adjusted their preferences to the new circumstances, or they have been replaced by political competitors holding “more appropriate” preferences.

In this context, voters are clearly inconsistent, since they would like to see high tax pressure (populism), but they are unwilling to pay for it (low quality of public expenditure).

We follow the same line of reasoning presented at the beginning section 3.1: under low populism, the policymakers at the helm are likely to be characterized by integrity and statesmanship (low propensity towards rent-seeking).

If the consequences of a longer time horizon are substantial, however, the reduction in the wastages related to corruption and privileges can bring about a higher quality of public expenditure (QE O > QE C ) and thus a higher level of tolerable tax expenditure.

See the explanation offered in section 3.2.

The term “harmful competition” is usually employed to describe the behaviour of those low-tax countries that fail to disclose full information about their taxpayers, and therefore stifle HT efforts to go after their residents who decide to move their wealth abroad. In this vein, Lampreave (2011) provides plenty of references to official documents issued by international organizations recommending that, in the presence of harmful competition, governments “should put severe restrictions on capital exports and bring the marginal product of domestic capital to a level which is even below the world rate of interest” (Razin and Sadka 1990: 7).

As documented extensively in Grinberg (2012), given a choice between obtaining a list of wealth owners and being credited a sum proportional to the wealth the HT residents hold abroad (and no disclosure of the owners’ names), HT countries prefer the former. From their point of view, the introduction of a substitute anonymous withholding tax is less satisfactory on two accounts. First, it ultimately leaves the LT country with the power to define the withholding tax rate, which may not suit the preferences of the HT countries or follow changes in their legislation. Second, the principles of anonymity and withholding are porous: they weaken the possibility of taxing the stock of wealth held by HT citizens and require cooperation from all LT jurisdictions, lest wealth moves to less hostile environments.

In a free-market society, any actor can of course decide to cooperate with a foreign government and regularly exchange all sorts of information, as long as this exchange is not explicitly forbidden by a contractual agreement previously signed with a third party. Yet, in a free-market society, any potential financial intermediary has a right to offer its customers a commitment to secrecy and no-cooperation with any kind of authority.

The major instrument through which HTs succeed in coercing foreign financial intermediaries to acquiesce to their requests is by denying them access to their financial markets and possibly seizing their assets. As a result, it is hardly surprising that financial intermediaries located in LTs put pressure on their own governments to compromise with HTs, and also that they lobby for regulation that aims at forestalling entry by new actors less inclined to compromise.

Tax harmonization differs from tax centralization. The former relates to the existence of different tax systems that remain subject to different and sovereign jurisdictions. In contrast with a harmonized system, centralization implies centralized control on taxation and expenditure and makes opting out by dissenting jurisdictions more difficult.

In a national game, the players are the electorate, the policymakers, and selected interest groups. In a supranational centralized game, the main players would be the technocrats and the policymakers at the centre, and the interest groups with privileged access to those technocrats and policymakers. Local politicians and voters would be all but marginalized.

In a similar vein, Eppink (2010, chapter 5) has drawn attention to a different strategy currently pursued by the EU elites. This strategy involves two steps. First, Brussels would reduce the size of the members’ contributions to the central budget in exchange for the recognition of Brussels’ autonomous taxing power. Then, the EU parliament would gradually increase the federal tax pressure, without interference from the member countries.

Bagus (2010) has drawn attention to the fact that technocratic decisions are in fact a veil behind which ideological and political designs are pursued, for example in the area of monetary economics.

References

Bagus, P. (2010). The tragedy of the Euro. Auburn: Ludwig von Mises Institute.

Bartlett, B. (2012). What is the revenue-maximizing tax rate? Tax Notes, 134(8), 1013–1015.

Bergh, A., & Henrekson, M. (2011). Government size and growth: a survey and interpretation of the evidence. Journal of Economic Surveys, 25(5), 872–897.

Buchanan, J. (1967). Public finance in democratic process: Fiscal institutions and individual choice. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. reprinted in Indianapolis (1999): Liberty Fund.

Buchanan, J., & Lee, D. (1984). Some simple analytics of the Laffer curve. In H. Hanush (Ed.), Public finance and the quest for efficiency (pp. 281–295). Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Canto, V. A., Joines, D. H., Laffer, A. B. (1978). “Taxation, GNP and potential GNP”. Proceedings of the Business and Economic Statistics Section in San Diego (pp. 122–130). American Statistical Association.

Clausing, K. (2007). Corporate tax revenues in OECD countries. International Tax and Public Finance, 14(2), 115–133.

Creedy, J., & Gemmell, N. (2012). “Revenue-maximizing elasticities of taxable income in multi-rate income tax structures”. Working Papers in Public Finance, 5, August, Victoria University of Wellington.

De Mooij, R., & Vrijburg, H. (2012). “Tax rates as strategic substitutes”. Tinbergen Institute Discussion Paper, TI 2012-104/VI.

Devereux, M., Lockwood, B., & Redoano, M. (2008). Do countries compete over corporate tax rates? Journal of Public Economics, 92(5–6), 1210–1235.

Dupuit, J. (1844). “De la mesure de l‘utilité des travaux publiques”. Annales des Ponts et Chaussées, reprinted and translated in K. Arrow and T. Scitovski (eds, 1969), AEA Readings in Welfare Economics, pp. 225–283.

Entin, S. (2009). “The effect of the capital gains tax rate on economic activity and total tax revenue”. Capital Gains Series, IRET (Washington, DC), 1, October 9.

Eppink, D. J. (2010). Bonfire of bureaucracy in Europe. Tielt: Lannoo.

Evans, P. (2009). “The relationship between realized capital gains and their marginal rate of taxation, 1976–2204”. Capital Gains Series, IRET (Washington, DC), 2, October 9.

Feige, E., & McGee, R. (1983). Sweden’s Laffer curve: taxation and the unobserved economy. Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 85(4), 499–519.

Grinberg, I. (2012). Beyond FACTA: an evolutionary moment for the international tax system. Georgetown University Law Centre, January, downloadable from http://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/fwps_papers/160.

Higgs, R. (1991). Eighteen problematic propositions in the analysis of the growth of government. Review of Austrian Economics, 5(1), 3–40.

Lampreave, P. (2011). “Fiscal competitiveness versus harmful tax competition in the European Union”. Bulletin for International Taxation, 65(6), available at ssrn.com/abstract=1932257.

Mankiw, G., Weinzierl, M., & Yagan, D. (2009). Optimal taxation in theory and practice. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 23(4), 147–174.

Meltzer, A., & Richard, S. (1983). Tests of a rational theory of the size of government. Public Choice, 41, 403–418.

Mirowski, P. (1982). What’s wrong with the Laffer curve? Journal of Economic Issues, 16(3), 815–828.

Mutti, J. H. (2003). Foreign direct investments and tax competition. Washington: IIE Press.

Olson, M. (1982). The rise and decline of nations. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Puviani, A. (1903). Teoria della Illusione Finanziaria. Firenze: Remo Sandron. reprinted in Milano (1973): Istituto Editoriale Internazionale.

Razin, A., & Sadka, E. (1990). “Capital market integration: Issues of international taxation”. NBER Working Papers, no. 3281, March.

Salotti, S., & Trecroci, C. (2012). “Even worse than you thought: The impact of government debt on aggregate investment and productivity”, April, available at http://ssrn.com/abstract=2033107.

Sen, A. (1999). Development as freedom. New York: Anchor Books.

Smith, A. (1981/1776). An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations. In: R. H. Campbell & A. S. Skinner (Eds), Vol. II of the Glasgow edition of the works and correspondence of Adam Smith. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund.

Théret, B., & Uri, D. (1988). La courbe de Laffer dix ans après: un essai de bilan critique. Revue Économique, 39(4), 753–808.

Wagner, A. (1911). “Staat in nationalökonomischer Hinsicht”. Handwörterbuch der Staatswissenchaften, Book VII, pp. 743–745.

Wanniski, J. (1978). The way the world works. New York: Basic Books.

Acknowledgments

Niclas Berggren, Christine Henderson, David Lipka and two referees of this Review read previous drafts of this paper and contributed very valuable comments. I thank them all.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Colombatto, E. An alternative to the Laffer curve: Theory and consequences. Rev Austrian Econ 28, 75–92 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11138-013-0249-1

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11138-013-0249-1