Abstract

Poor participant engagement threatens the potential impact and cost-effectiveness of public health programmes preventing meaningful evaluation and wider application. Although barriers and levers to engagement with public health programmes are well documented, there is a lack of proven strategies in the literature addressing these. This paper details the development of a participant engagement intervention aimed at promoting enrolment and attendance to a community-based pre-school obesity prevention programme delivered in UK children’s centres; HENRY (Health, Exercise, Nutrition for the Really Young). The Behaviour Change Wheel framework was used to guide the development of the intervention. The findings of a coinciding focused ethnography study identified barriers and levers to engagement with HENRY that informed which behaviours should be targeted within the intervention to promote engagement. A COM-B behavioural analysis was undertaken to identify whether capability, opportunity or motivation would need to be influenced for the target behaviours to occur. APEASE criteria were used to agree on appropriate intervention functions and behaviour change techniques. A multi-level participant engagement intervention was developed to promote adoption of target behaviours that were proposed to promote engagement with HENRY, e.g. ensuring the programme is accurately portrayed when approaching individuals to attend and providing ‘taster’ sessions prior to each programme. At the local authority level, the intervention aimed to increase buy-in with HENRY to increase the level of resource dedicated to engagement efforts. At the centre level, managers were encouraged to widen promotion of the programme and ensure that staff promoted the programme accurately. HENRY facilitators received training to increase engagement during sessions, and parents that had attended HENRY were encouraged to recruit their peers. This paper describes one of the first attempts to develop a theory-based multi-level participant engagement intervention specifically designed to promote recruitment and retention to a community-based obesity prevention programme. Given the challenges to implementing public health programmes with sufficient reach, the process used to develop the intervention serves as an example of how programmes that are already widely commissioned could be optimised to enable greater impact.

Similar content being viewed by others

Background

Local authorities in England are responsible for improving the health and well-being of people living in their communities. This includes providing equitable access to public health programmes that promote positive lifestyle behaviours. Populations living in the most deprived areas of England are more likely to have higher rates of smoking, poor mental health and obesity than those (Public Health England 2019) from more affluent areas.

Community-based public health programmes that are adopted and implemented as planned by local authorities have the potential to promote health and reduce heath inequalities. However, a major barrier which hinders their effective implementation is poor participant engagement (enrolment and completion). Poor engagement reduces potential impact of public health programmes, with greater uptake and reach being associated with better outcomes for participants (Bamberger et al. 2014). The cost-effectiveness of programmes is also reduced, with literature showing an increased cost per person when classes do not run with the intended number of people, often resulting in programmes ending prematurely or being cancelled before they start (Lindsay et al. 2014). Further, poor engagement hinders evaluation efforts, preventing wider application.

Engaging participants with public health programmes is known to be a challenge (Morawska et al. 2011). This is particularly pertinent to prevention interventions that are aimed at a general population rather than a targeted group (Spoth and Redmond 2000) in which potential participants may perceive a lack of relevance, experience no clinical symptoms or be hesitant to receive unwanted lifestyle advice (Harte et al. 2018). The literature describes many barriers to engagement with public health interventions such as lack of time, cost of public transport and social and cultural barriers (La Placa and Corlyon 2014) which suggest that programme deliverers should invest resources into the design, delivery and evaluation of engagement strategies aimed at addressing these barriers. Yet studies reporting on such efforts are few, and there is a particular lack of studies that have rigorously evaluated an engagement strategy.

A public health programme that is currently widely delivered in the UK (delivered in 32 local authorities, providing more than 150 programmes per year) is HENRY; Health, Exercise and Nutrition for the Really Young, a pre-school obesity prevention programme predominately delivered in children’s centres. HENRY is an 8-week group parenting programme (2 h per week) that aims to prevent the development of obesity in young children by supporting the whole family to make positive lifestyle change to create a healthy and happy home environment (HENRY 2020). The programme includes elements on parent and child well-being, parenting skills, healthy mealtimes and active lifestyles. Initial evaluation findings of the programme are promising and show that it may have a positive impact on families and practitioners (Willis et al. 2012; Willis et al. 2016). However, implementation data indicate that some local authorities and children’s centres fail to meet their enrolment and engagement targets of eight families per programme and completion of a minimum of five out of the eight sessions, threatening its potential impact and sustainability.

This aim of this paper is to describe the development of a participant engagement intervention aimed at supporting children’s centres and local authorities to promote parent engagement with the existing HENRY programme. Outlined in the paper is the intervention development process which was informed by the Behaviour Change Wheel (Michie et al. 2011) and a description of the final intervention design. Although this intervention is focused on promoting parent engagement with HENRY, it has been developed with transferability in mind so that it has the potential to be adapted for other community-based interventions.

Methods

Intervention Development Team

A multi-disciplinary team was convened to develop the participant engagement intervention which included experts in intervention development, obesity, applied health research and behaviour change; a local authority (local government) representative; a HENRY parent; and the chief executive of HENRY. The intervention development team met five times during the 6-month intervention development process (July to December 2015) with tasks completed between meetings. A parent advisory group was also consulted during the intervention development to discuss barriers and facilitators to engagement with HENRY and gain feedback for intervention components.

Literature Review

Prior to the development of the intervention, a comprehensive review of the relevant literature was conducted to identify interventions that had previously been tried and tested to promote engagement with a public health programme.

Focused Ethnography Study

During the development of the engagement intervention, a focused ethnography study was undertaken to provide primary evidence about the factors influencing parent engagement with HENRY. Key findings of the ethnography were used to inform the development of the intervention. The ethnography study methods and results have already been published elsewhere (Burton et al. 2019) and are therefore only briefly described here. During the ethnography study, five children’s centres were visited that delivered HENRY across the UK, with 190 h of field observations, 22 staff interviews (commissioners, HENRY co-ordinators, managers and facilitators) and six parent focus groups (36 parents). The aim of the study was to identify barriers and levers to engagement with HENRY within the children’s centre context from the perspective of individuals involved in its implementation along with parents visiting the centre.

Behaviour Change Wheel Framework

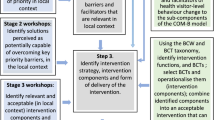

The Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) (Michie et al. 2011) was used as a guide to develop the intervention which is underpinned by the COM-B (capability, opportunity, motivation) model of behaviour, which proposes that one or more of its behavioural components need to be influenced for behaviour change to occur. The BCW approach involves 3 stages of intervention development: Stage 1, specifying the target behaviours and identifying what needs to change; Stage 2, identifying intervention functions (the ways in which the intervention will operate); and Stage 3, identifying the content and implementation options. The intervention development process we adopted is summarised in Fig. 1.

Behaviour Change Wheel Stage 1: Specifying Target Behaviours and Identifying What Needs to Change

Defining the Problem in Behavioural Terms

To understand how to promote participant engagement with HENRY, the development team considered data from the ethnography study, key literature surrounding engagement with parenting programmes (e.g. Mytton et al. 2014), the implementation of public health programmes (e.g. Damschroder et al. 2009) and their own experience and expertise to identify the main barriers and levers to engagement. This was translated into a ‘long list’ of target behaviours that could potentially be addressed within the intervention.

Selecting Target Behaviours

The BCW advises that the number of behaviours targeted within an intervention should be limited as a small number of successes is more likely to be effective than trying to do too much at once (Michie et al. 2014); therefore, the ‘long list’ of behaviours was narrowed down to a ‘short list’ of target behaviours using decision-making guidance from the BCW. This process involved structured discussions where the team used the evidence to categorise each behaviour as promising, very promising, unpromising but worth considering and unacceptable. Categorisation was achieved by considering the expected impact of the behaviour change, the likelihood of changing the behaviour, anticipated wider impact (‘spill over score’) and the behaviour change measurability. A ranking exercise then took place whereby each development team member individually selected their ‘top ten’ target behaviours from the promising or very promising behaviours list, assigning each a score of 1 to10, considering which were achievable within existing funds and timescales of the delivery period. Team members were permitted to prioritise fewer or more than ten if necessary. The scores were then collated and the highest scoring was added to the short list. Where a team member felt strongly that additional behaviours should be added to the short list, further discussions were held until consensus was reached.

Identifying What Needs to Change

Once the target behaviours had been selected, a ‘behavioural analysis’ was undertaken utilising the COM-B model of behaviour. This exercise is central to the BCW approach and involved the team drawing upon their experience and expertise and ethnography study findings to consider whether an individual’s capability, opportunity or motivation would need to be influenced for the target behaviours to occur.

Stage 2: Identifying Intervention Options

The next stage was to identify the most appropriate intervention functions to incorporate in the intervention that would have the best chance of influencing capability, opportunity or motivation; based on the behavioural analysis described above, available resources and contextual factors. The BCW offers the following suggestions of potential intervention functions: education, persuasion, incentivisation, coercion, training, restriction or environmental restructuring. To assist with decision-making around which intervention functions to include, the BCW suggests the use of the APEASE criteria (Michie et al. 2014) as a decision-making tool: affordability, practicability, effectiveness, acceptability, side effects and equity which the team used to structure group discussions.

Stage 3: Identifying Content and Implementation Options

The next stage was to decide on which behaviour change techniques to include (Michie et al. 2013). The BCW matches each potential intervention function selected in Stage 2 to a list of appropriate behaviour change techniques based on a consensus reached by experts in behaviour change (Michie et al. 2011). The intervention development team considered the evidence within the context of the children’s centre/local authority setting and again drew upon APEASE criteria and their own experience of HENRY and children’s centres to decide on the final behaviour change techniques to include.

Once the intervention function and behaviour change techniques had been selected, the most appropriate and realistic mode of delivery was agreed.

Results

Literature Review

The review identified five types of engagement interventions that had been tested to promote engagement with a public health programme: incentives, programme setting, manipulated promotional strategies, text message reminders and testimonials. Overall, none of the intervention types was consistently effective at promoting all stages of engagement, but monetary incentives were largely successful at promoting enrolment (Diaz and Perez 2009; Dumas et al. 2010; Heinrichs 2006; Hennrikus et al. 2002) and text message reminders were effective at promoting completion rates (Murray et al. 2015). This indicated that a multi-component intervention may be needed to enhance engagement at various stages.

Stage 1

Defining the Problem in Behavioural Terms

The results of the ethnography study are reported elsewhere (Burton et al. 2019), and therefore, only a brief summary is provided here to support describing the intervention development. The findings of the ethnography were consistent with what has previously been reported in the literature regarding participant level barriers to engagement with parenting programmes, e.g. programme acceptability, group dynamics and the personal attributes of the group facilitator (Beatty and King 2008; Friars and Mellor 2009; Gross et al. 2001; Owens et al. 2007; Pearson and Thurston 2006; Wheatley et al. 2003;). The study also revealed that engagement with HENRY was influenced by implementation factors that were present across multiple operational levels within the children’s centre/local authority context. In particular, a hierarchical spill-over affect was observed, whereby local authority ‘buy-in’ of HENRY cascaded down to children’s centre implementation of the programme which subsequently influenced how participants perceived and experienced the programme. A further finding of the ethnography study revealed that, although stakeholders acknowledged that some behaviours were likely to facilitate participant engagement with HENRY (e.g. HENRY training for all staff), practical barriers such as funding availability and capacity limited their ability to adopt them. Therefore, the problem defined in behavioural terms as to why centres struggled to recruit and retain participants on the HENRY programmes was that children’s centre stakeholders (commissioners, managers and centre staff) did not (or were not able to) adopt behaviours that were likely to promote participant engagement.

Selecting the Target Behaviour

The shortlisting exercise resulted in a list of target behaviours proposed to promote engagement with HENRY that were to be performed by commissioners, managers, staff, HENRY facilitators and HENRY parents (parents that had previously attended HENRY) (Table 1). This included the delivery of ‘taster’ sessions prior to each delivered programme so that parents would gain a full understanding of what the programme entailed prior to enrolling, and the provision of HENRY training for all staff working in the centres so that they could provide an accurate representation of the programme when approaching parents to attend.

Identifying What Needs to Change

The COM-B behavioural analysis determined the direction of the intervention at each level (Table 2). For example, it was agreed that centre managers were capable of adopting the target behaviours proposed to promote engagement with HENRY, but in order to adopt them, they would need to have the relevant support (social opportunity) from local authority commissioners, e.g. financial support. In addition, managers would need to be motivated to adopt them. Therefore, in order for the target behaviours to occur at the manager level, the intervention would need to influence social opportunity and motivation.

Stage 2: Identifying Intervention Options

The team agreed that the intervention would educate commissioners on why HENRY was beneficial to families in their community to increase their buy-in with the programme. It was also agreed that the intervention would educate them on the benefits of adopting the target behaviours in terms of promoting cost-effectiveness and programme reach. The intervention also aimed to enable commissioners to provide support to managers by providing them with data on the outcomes achieved by families that attend (e.g. changes to eating habits) so that they could make informed decisions about how much resource should be invested into engagement efforts. Gaining support from commissioners was proposed to enable managers to adopt the target behaviours. The intervention also aimed to motivate managers to adopt the target behaviours by persuading them on why it would be beneficial to do so. Similarly, gaining appropriate buy-in from managers was proposed to enable staff members to promote HENRY accurately, e.g. through means of training provision. The intervention also aimed to persuade staff members to promote HENRY accurately by encouraging managers to share information with them on how HENRY benefits families that attend. At the facilitator lever, it was agreed that facilitators would be trained on how to adopt the target behaviours, along with persuading them to do so by providing information on the expected benefits. Parents that had attended a HENRY programme would be educated on why it would be beneficial for them to recruit their peers, along with them being enabled to do so by providing them with any resources or support they might need.

Stage 3: Identifying Content and Implementation Options

Behaviour change techniques selected to carry out each intervention function are described in Table 3 along with the associated intervention component.

Participant Engagement Intervention Components

The HENRY participant engagement intervention comprises six components: commissioner outcome report, commissioner overview leaflet, manager dashboard report, manager information workshops, HENRY facilitator refresher training and revised promotional material. As mentioned, specific details on behaviour change techniques delivered within each intervention component are provided in Table 3.

Commissioner Report

Existing processes at HENRY central office included the provision of outcome data to commissioners HENRY prior to the intervention. However, during the ethnography study, it was revealed that these data were not received often enough and at the appropriate time points to assist with decision-making around levels of investment. Therefore as part of the information, reporting procedures were tightened so that commissioners would receive an outcome report quickly at the end of each programme delivery period (usually delivered in line with school periods, i.e. four monthly). Outcomes included in the report are enrolment and attendance, participant feedback and behaviour change outcomes from the start to the end of the programme (e.g. changes to family eating habits).

Commissioner Overview Leaflet

The commissioner overview leaflet was designed to increase local authority buy-in with HENRY and the participant engagement intervention by providing commissioners with information on how HENRY aligns with national public health targets and the proposed benefits of managers adopting the target behaviours. The leaflet is circulated to commissioners that deliver HENRY programmes prior to the start of the intervention delivery period to gain support for intervention activities.

Dashboard Report

The dashboard report is a one-page report designed to persuade managers to adopt the target behaviours. The report is sent to all managers that deliver HENRY within their children's centre at the start of the intervention and after each delivered programme thereafter. The report provides feedback to managers on parent engagement outcomes achieved for the previous HENRY programme and summarise behaviour change outcomes achieved by the parent e.g. changes in parent and child fruit and vegetable intake as a result of attending. Managers are also encouraged to share the information provided in the report with centre staff so that they can also made aware of the benefits to families as a result of attending HENRY.

Manager Information Workshops

The manager information workshop was designed to be attended by all managers that deliver HENRY programmes within their centre. The 1-day workshop is delivered at the start of the intervention. During the workshops, managers are briefed on the aims of the HENRY participant engagement intervention and proposed logic model. Group discussions and activities also take place around the proposed benefits of adopting the target behaviours, goal setting and action planning on how the behaviours could be implemented within their setting. Managers also have the opportunity to discuss anticipated barriers to performing the behaviours and share knowledge on how these may be overcome.

Facilitator Refresher Training

Facilitator refresher training was deigned to be offered to all HENRY facilitators within a local authority that delivered HENRY programmes. The interactive training takes place over one full day where facilitators are briefed on the aims of the HENRY participant engagement information and the proposed benefits of adopting the target behaviours. Training and demonstrations on how to adopt the target behaviours are also provided. During the workshop, facilitators are also instructed to introduce ‘peer’ recruitment to parents that attend HENRY to encourage them to recruit their friends and family.

Revised Promotional Material

Existing HENRY promotional material was revised to more accurately portray what the HENRY programme entails. Included in this was this was a change to the tagline displayed on all promotional material from ‘Health, Exercise and Nutrition for the Really Young’ to ‘Healthy Family, Happy Home’ to better depict the holistic nature of the programme. The promotional material was designed to be displayed in all children’s centres delivering HENRY to attract potential participants. In addition, the promotional material also aimed to support children’s centre staff to accurately portray the programme and provide a resource for HENRY parents to be able to recruit their peers to the programme.

A logic model was developed by the intervention development team to outline how the participant engagement intervention proposed to promote engagement with HENRY (Online Resource 1). In brief, adoption of the target behaviours by commissioners, managers, staff, HENRY facilitators and HENRY parents proposed to increase support of parent engagement efforts; increase awareness and understanding of the programme among potential participants and centre staff; normalise the HENRY programme within the children’s centre and community, reducing stigma and negative perceptions; and optimise the participant experience to promote engagement during HENRY sessions, thus achieving greater reach and impact of the programme along with increased sustainability and cost-effectiveness.

Discussion

This paper describes the development of a theory-based participant engagement intervention aimed at supporting local authorities to promote engagement with a community delivered obesity prevention programme. Participant engagement with preventative public health programmes is central to achieving meaningful impact, yet there is a lack of studies rigorously evaluating the effect of strategies aimed at promoting engagement, and from those that have, few found a positive effect.

The majority of reported participant engagement interventions in the literature comprise of single strategies directed only at anticipated beneficiaries which are largely ineffective. Moreover, although reported strategies are mostly theoretically based, they are often not tailored to address particular barriers identified within a programme’s context. Participant engagement is likely influenced by multiple contextual factors such as organisational strategies, local implementation practices, intervention characteristics and the characteristics of individuals involved in a programme’s delivery (Rogers 1962, Damschroder et al. 2009, Burton et al. 2019). Thus, in theory, interventions aimed at multiple organisational levels have greater potential for promoting participant engagement with public health programmes. This participant engagement intervention addresses the multiple levels of influence that hinder effective programme implementation of HENRY. To our knowledge, this is the first study that has adopted this approach with the primary aim of optimising participant engagement with a public health programme.

The BCW provided a useful guide to develop this participant engagement intervention, offering valuable decision-making tools such as APEASE criteria. However, the focus on individual behaviour change directed by the COM-B model of behaviour was sometimes difficult to apply to a whole setting approach where hierarchical structures influence whether behaviour change is possible. In future, combining the BCW with another theoretical model may be beneficial. For example, Band et al. (2017) successfully utilised both the COM-B model of behaviour and Normalisation Process Theory (May et al. 2009) to develop an intervention which considered both individual level and organisation level factors in its design that was most relevant to the user population and setting.

The participant engagement intervention was designed using a rigorous and transparent process. Consulting with a parent advisory group was invaluable in learning how the wider impact of the intervention could ultimately influence participant engagement with HENRY. Incorporating an ethnography study also provided a thorough understanding of the setting in which HENRY is delivered which enabled a tailored intervention to be developed that addresses specific implementation barriers to participant engagement. The methods and insight gained through the development of the participant engagement intervention could be applied to other public health programmes delivered within a community setting. A limitation of the intervention development process was that stakeholders from the children’s centres were not involved in decision-making about the final intervention functions and components. However, they were important in identifying where intervention was needed through their ongoing involvement in the ethnographical research. Implementation of the participant engagement intervention did not include a piloting phase. Ideally, any intervention should be piloted prior to full implementation, but due to timeline and resources, this was not done here which is a recognised limitation.

The participant engagement intervention is currently being tested in a multi-site, cluster randomised controlled trial (Bryant et al. 2017); the results of which will be reported elsewhere when available. A comprehensive process evaluation will also report on the implementation of the intervention and explore the change mechanisms. Throughout the development of the participant engagement intervention, the development team have been mindful of the severe upheaval that has occurred throughout local authorities and children’s centre services in England in recent years which have led to substantial re-structuring and job losses (Sammons et al. 2015). The influence of these contextual factors on the implementation of programmes such as HENRY is yet unknown.

Conclusions

This paper describes an example of one of the first attempts to develop a multi-level participant engagement intervention designed to promote participant engagement with an obesity prevention programme, using HENRY as an example. Highlighted within the development process was the importance of identifying the barriers and levels within the implementation setting that promoted or hindered participant engagement. The use of the BCW framework served as a useful guide to consider which behavioural components needed to be influenced for behaviour change to occur before providing a transparent and systematic decision-making tool. Given the challenges to implementing public health programmes with sufficient reach, the process used to develop the participant engagement optimisation intervention serves as an example of how programmes that are already widely commissioned and have the potential to improve the health of the population could be optimised to enable greater impact.

Data Availability

Not applicable.

References

Bamberger, K. T., Coatsworth, J. D., Fosco, G. M., & Ram, N. (2014). Change in participant engagement during a family-based preventive intervention: Ups and downs with time and tension. Journal of Family Psychology: JFP, 28, 811.

Band, R., Bradbury, K., Morton, K., et al. (2017). Intervention planning for a digital intervention for self-management of hypertension: a theory-, evidence- and person-based approach. Implementation Science, 12, 25. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-017-0553-4.

Beatty, D., & King, A. (2008). Supporting fathers who have a child with a disability: The development of a new parenting program. Groupwork, 18, 66–87. https://doi.org/10.1921/81141.

Blaine, R. E., et al. (2017). Using school staff members to implement a childhood obesity prevention intervention in low-income school districts: The Massachusetts Childhood Obesity Research Demonstration (MA-CORD Project), 2012-2014. Preventing Chronic Disease, 14, E03.

Bloomquist, M. L., et al. (2013). Going-to-scale with the early risers conduct problems prevention program: Use of a comprehensive implementation support (CIS) system to optimize fidelity, participation and child outcomes. Evaluation and Program Planning, 38, 19–27.

Bryant, M., Burton, W., Cundill, B., Farrin, A. J., Nixon, J., Stevens, J., et al. (2017). Effectiveness of an implementation optimisation intervention aimed at increasing parent engagement in HENRY, a childhood obesity prevention programme - the Optimising Family Engagement in HENRY (OFTEN) trial: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials, 18, 40.

Burton, W., Twiddy, M., Sahota, P., Brown, J., & Bryant, M. (2019). Participant engagement with a UK community-based preschool childhood obesity prevention programme: a focused ethnography study. BMC Public Health, 19, 1074. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-019-7410-0.

Damschroder, L. J., Aron, D. C., Keith, R. E., Kirsh, S., Alexander, J. A., & Lowery, J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4, 50.

Davis, C. C., et al. (2012). Putting families in the center: Family perspectives on decision making and ADHD and implications for ADHD care. Journal of Attention Disorders, 16(8), 675–684.

Diaz, S. A., & Perez, J. M. E. (2009). Use of small incentives for increasing participation and reducing dropout in a family drug-use prevention program in a Spanish sample. Substance Use & Misuse, 44, 1990–2000.

Dumas, J. E., Begle, A., French, B., & Pearl, A. (2010). Effects of monetary incentives on engagement in the PACE parenting program. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 39, 302–313.

Friars, P., & Mellor, D. (2009). Drop-out from parenting training programmes: A retrospective study. Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 21(1), 29–38.

Gilbert, H., et al. (2017). Effectiveness of personal tailored risk information and taster sessions to increase the uptake of smoking cessation services (Start2quit) : a randomised controlled trial. Lancet, 389(10071), 823–833.

Gross, D., Julion, W., & Fogg, L. (2001). What motivates participation and dropout among low-income urban families of color in a prevention intervention? Family Relations, 50, 246–254.

Harte, E., MacLure, C., Martin, A., Saunders, C. L., Meads, C., Walter, F. M., et al. (2018). Reasons why people do not attend NHS health checks: A systematic review and qualitative synthesis. British Journal of General Practice, 68(666), e28–e35. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp17X693929.

Heinrichs, N. (2006). The effects of two different incentives on recruitment rates of families into a prevention program. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 27, 345–365.

Hennrikus, D. J., Jeffery, R. W., Lando, H. A., Murray, D. M., Brelje, K., Davidann, B., Baxter, J. S., Thai, D., Vessey, J., & Liu, J. (2002). The SUCCESS project: The effect of program format and incentives on participation and cessation in worksite smoking cessation programs. American Journal of Public Health, 92, 274–279.

HENRY, 2020. What is HENRY? [online]. Oxfordshire: HENRY. Available: https://www.henry.org.uk/about [accessed 09/11/2020].

La Placa, V., & Corlyon, J. (2014). Barriers to inclusion and successful engagement of parents in mainstream services: Evidence and research. Journal of Children's Lervices, 9, 220–234.

Lindsay, G., Strand, S., Cullen, M., Cullen, S., Band, S., Davis, H., Conlon, G., Barlow, J., & Evans, R. (2014). Evaluation of the parenting early intervention programme: A short report to inform local commissioning processes. DFE-RR121(b) [online] Department for Education, p.13. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/318123/DFE-RR121B.pdf. Accessed 25 Jan 2021.

May, C. R., Mair, F., Finch, T., MacFarlane, A., Dowrick, C., Treweek, S., Rapley, T., Ballini, L., Ong, B. N., Rogers, A., Murray, E., Elwyn, G., Légaré, F., Gunn, J., & Montori, V. M. (2009). Development of a theory of implementation and integration: Normalization Process Theory. Implementation Science, 4, 29. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-29.

Michie, S., Van Stralen, M., & West, R. (2011). The behaviour change wheel: A new method for characterising and designing behaviour change interventions. Implementation Science, 6, 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-6-42.

Michie, S., Richardson, M., Johnston, M., Abraham, C., Francis, J., Hardeman, W., et al. (2013). The behavior change technique taxonomy (v1) of 93 hierarchically clustered techniques: Building an international consensus for the reporting of behavior change interventions. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 46(1), 81–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-013-9486-6.

Michie, S., Atkins, L., & West, R. (2014). The behaviour change wheel: A guide to designing interventions. London: Silverback Publishing.

Morawska, A., Nitschke, F., & Burrows, S. (2011). Do testimonials improve parental perceptions and participation in parenting programmes? Results of two studies. Journal of child health care : for professionals working with children in the hospital and community, 15, 85–98.

Murray, K. W., Woodruff, K., Moon, C., & Finney, C. (2015). Using text messaging to improve attendance and completion in a parent training program. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 3107–3116.

Mytton, J., Ingram, J., Manns, S., & Thomas, J. (2014). Facilitators and barriers to engagement in parenting programs: A qualitative systematic review. Health Education & Behavior, 41, 127–137.

Owens, J., Richerson, L., Murphy, C., Jageleweski, A., & Rossi, L. (2007). The parent perspective: Informing the cultural sensitivity of parenting programs in rural communities. Child & Youth Care Forum, 36, 179–194.

Pearson, C., & Thurston, M. (2006). Understanding mothers’ engagement with antenatal parent education services: A critical analysis of a local sure start service. Children & Society, 20, 348–359.

Public Health England. (2019). Protecting and improving the nation’s health: Phe strategy 2020-2025. london: Public Health England.

Rogers, E. M. (1962). Diffusion of innovations. New York: Free Press of Glencoe.

Sammons, P., Hall, J., Smees, R., & Goff, J. (2015). The impact of children’s centres: Studying the effects of children's centres in promoting better outcomes for young children and their families. Oxford: Department for Education.

Spoth, R., & Redmond, C. (2000). Research on family engagement in preventive interventions: Toward improved use of scientific findings in primary prevention practice. Primary Prevention, 21, 267–284.

Wheatley, S. L., Brugha, T. S., & Shapiro, D. A. (2003). Exploring and enhancing engagement to the psychosocial intervention ‘Preparing for Parenthood’. Archives of Women's Mental Health, 6, 275–285.

Willis, T. A., Potrata, B., Hunt, C., & Rudolf, M. C. J. (2012). Training community practitioners to work more effectively with parents to prevent childhood obesity: The impact of henry upon children’s centres and their staff. Journal of Human Nutrition and Dietetics, 25(5), 460–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-277X.2012.01247.x.

Willis, T., Robers, K. P. J., Berry, T. M., Bryant, M., & Rudolf, M. C. J. (2016). The impact of HENRY on parenting and family lifestyle: A national service evaluation of a preschool obesity prevention programme. Public Health, 136, 101–108.

Funding

The trial is funded by the NIHR Trainees Coordinating Programme awarded to XX (co-author) (CDF-2014-07-052).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable.

Ethics Approval

The study was performed in accordance with the ethical standards as laid down in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The research was approved by University of Leeds School of Medicine Research Ethics Committee (MREC16–107).

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Burton, W., Sahota, P., Twiddy, M. et al. The Development of a Multilevel Intervention to Optimise Participant Engagement with an Obesity Prevention Programme Delivered in UK children’s Centres. Prev Sci 22, 345–356 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-021-01205-y

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-021-01205-y