Abstract

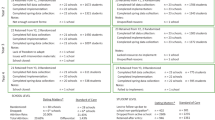

Dating violence is a significant problem in Mexico. National survey data estimated 76 % of Mexican youth have been victims of psychological aggression in their relationships; 15.5 % have experienced physical violence; and 16.5 % of women have been the victims of sexual violence. Female adolescents perpetrate physical violence more frequently than males, while perpetration between genders of other types of violence is unclear. Furthermore, poor, marginalized youth are at a higher risk for experiencing dating violence. “Amor… pero del Bueno” (True Love) was piloted in two urban, low-income high schools in Mexico City to prevent dating violence. The intervention consisted of school-level and individual-level components delivered over 16 weeks covering topics on gender roles, dating violence, sexual rights, and strategies for coping with dating violence. The short-term impact was assessed quasi-experimentally, using matching techniques and fixed-effects models. A sample of 885 students (381 students exposed to the classroom-based curriculum of the individual-level component (SCC, IL-1) and 540 exposed only to the school climate component (SCC)) was evaluated for the following: changes in dating violence behaviors (psychological, physical and sexual), beliefs related to gender norms, knowledge, and skills for preventing dating violence. We found a 58 % (p < 0.05) and 55 % (p < 0.05) reduction in the prevalence of perpetrated and experienced psychological violence, respectively, among SCC, IL-1 males compared to males exposed only to the SCC component. We also found a significant reduction in beliefs and attitudes justifying sexism and violence in dating relationships among SCC, IL-1 females (6 %; p < 0.05) and males (7 %; p < 0.05).

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

We found baseline differences between students who only responded to the baseline survey and those with baseline and follow-up measurements: a greater proportion of students with only baseline data reported that they had already worked, had begun their sexual life, had lower school grades and were older. By contrast, a larger proportion of the students with both measurements reported that they were full-time students.

References

Achyut, P., Bhatla, N., Khandekar, S., Maitra, S., & Verma, R. K. (2011). Building support for gender equality among young adolescents in school: Findings from Mumbai, India. New Delhi: ICRW.

Ackard, D. M., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2002). Date violence and date rape among adolescents: Associations with disordered eating behaviors and psychological health. Child Abuse and Neglect, 26, 455–473.

Avery-Leaf, S., Cascardi, M., O’Leary, K. D., & Cano, A. (1997). Efficacy of a dating violence prevention program on attitudes justifying aggression. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 21, 11–17.

Banyard, V. L., & Cross, C. (2008). Consequences of teen dating violence: Understanding intervening variables in ecological context. Violence Against Women, 14, 998–1013. doi:10.1177/1077801208322058.

Bell, K. M., & Naugle, A. E. (2008). Intimate partner violence theoretical considerations: Moving towards a contextual framework. Clinical Psychology Review, 28, 1096–1107.

Bergman, L. (1992). Dating violence among high school students. Social Work, 37, 21–27.

Calvillo, R. N. (2010). Latino teens at risk: The effectiveness of dating violence prevention programs.

Coker, A. L., McKeown, R. E., Sanderson, M., Davis, K. E., Valois, R. F., & Huebner, E. S. (2000). Severe dating violence and quality of life among South Carolina high school students. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 19, 220–227.

Cornelius, T. L., & Resseguie, N. (2007). Primary and secondary prevention programs for dating violence: A review of the literature. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 12, 364–375.

Dehejia, R., & Wahba, S. (2002). Propensity score matching options for non-experimental causal studies. Review of Economics and Statistics, 84, 151–161.

De La Rue, L., Polanin, J. R., Espelage, D. L., & Pigott, T. D. (2016). A meta-analysis of school-based interventions aimed to prevent or reduce violence in teen dating relationships. Review of Educational Research, 0034654316632061.

Díaz -Aguado, M. J., Martínez, R., & Martín, G. (2004). La violencia entre iguales en la escuela y en el ocio. Estudios comparativos e instrumentos de evaluación. Prevención de la violencia y lucha contra la exclusión desde la adolescencia (Vol. 1). Madrid, España: Instituto de la Juventud.

Enriquez, M., Kelly, P. J., Cheng, A. L., Hunter, J., & Mendez, E. (2012). An intervention to address interpersonal violence among low-income Midwestern Hispanic-American teens. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 14, 292–299.

Font-Calafell, E. (2006). Dating violence prevention in ethnically diverse middle and high schools: Program evaluation results and prevalence rates among adolescents. Persistently Safe Schools. Collaborating with Students, Families, and Communities.

Foshee, V. A. (1996). Gender differences in adolescent dating abuse prevalence, types, and injuries. Health Education Research, 11, 275–286.

Foshee, V. A., Bauman, K. E., Ennett, S. T., Suchindran, C., Benefield, T., & Linder, G. F. (2005). Assessing the effects of the dating violence prevention program “safe dates” using random coefficient regression modeling. Prevention Science, 6, 245–258. doi:10.1007/s11121-005-0007-0.

Foshee, V. A., Benefield, T. S., Ennett, S. T., Bauman, K. E., & Suchindran, C. (2004). Longitudinal predictors of serious physical and sexual dating violence victimization during adolescence. Preventive Medicine, 39, 1007–1016. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2004.04.014.

Gamache, D. (1991). Domination and control: The social context of dating violence. In B. Levy (Ed.), Dating violence: young women in danger.

Gonzalez-Guarda, R. M., Cummings, A. M., Becerra, M., Fernandez, M. C., & Mesa, I. (2013). Needs and preferences for the prevention of intimate partner violence among Hispanics: A community’s perspective. The Journal of Primary Prevention, 34, 221–235.

Gonzalez-Guarda, R. M., Ortega, J., Vasquez, E. P., & De Santis, J. (2009). La mancha negra: Substance abuse, violence, and sexual risks among Hispanic males. Western Journal of Nursing Research.

Heise, L. (2011). What works to prevent partner violence? An evidence overview.

Hickman, L. J., Jaycox, L. H., & Aronoff, J. (2004). Dating violence among adolescents prevalence, gender distribution, and prevention program effectiveness. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 5, 123–142.

Instituto Mexicano de la Juventud (2007). Encuesta Nacional de Violencia en las Relaciones de Noviazgo 2007. Instituto Mexicano de la Juventud.

INMUJERES. Instituto Nacional de las Mujeres (2009). Encuesta Nacional de Exclusión, Intolerancia y Violencia en Escuelas Públicas de Educación Media Superior (ENEIVEMS) 2009.

Jaycox, L. H., McCaffrey, D., Eiseman, B., Aronoff, J., Shelley, G. A., Collins, R. L., & Marshall, G. N. (2006). Impact of a school-based dating violence prevention program among Latino teens: Randomized controlled effectiveness trial. Journal of Adolescent Health, 39, 694–704.

Klevens, J. (2007). An overview of intimate partner violence among Latinos. Violence Against Women, 13, 111–122.

Krajewski, S., Rybarik, M., Dosch, M., & Gilmore, G. (1996). Results of a curriculum intervention with seventh graders regarding violence in relationships. Journal of Family Violence, 11, 93–112.

Lazarevich, I., Irigoyen-Camacho, M. E., Velazquez-Alva, M. D., & Salinas-Avila, J. (2015). Dating violence in Mexican college students: Evaluation of an educational workshop. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. doi:10.1177/0886260515585539.

Malik, S., Sorenson, S. B., & Aneshensel, C. S. (1997). Community and dating violence among adolescents: Perpetration and victimization. Journal of Adolescent Health, 21, 291–302.

Moreno, C. L. (2007). The relationship between culture, gender, structural factors, abuse, trauma, and HIV/AIDS for Latinas. Qualitative Health Research, 17, 340–352.

O’Keeffe, N. K., Brockopp, K., & Chew, E. (1986). Teen dating violence. Social Work, 31, 465–468.

Oscós-Sánchez, M. Á., Lesser, J., & Oscós-Flores, L. D. (2013). High school students in a health career promotion program report fewer acts of aggression and violence. Journal of Adolescent Health, 52, 96–101.

Pacifici, C., Stoolmiller, M., & Nelson, C. (2001). Evaluating a prevention program for teenagers on sexual coercion: A differential effectiveness approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 69, 552–559.

Redondo, G., Ramis, M., Girbιs, S., & Schubert, T. (2011). Attitudes on gender stereotypes and gender-based violence among youth. Daphne III programme: Youth4Youth: Empowering young people in preventing gender-based violence through peer education.

Regan, M. E. (2009). Implementation and evaluation of a youth violence prevention program for adolescents. The Journal of School Nursing, 25, 27–33. doi:10.1177/1059840508329300.

Rijsdijk, L. E., Bos, A. E., Ruiter, R. A., Leerlooijer, J. N., de Haas, B., & Schaalma, H. P. (2011). The World Starts With Me: A multilevel evaluation of a comprehensive sex education programme targeting adolescents in Uganda. BMC Public Health, 11, 334.

Santana, M. C., Raj, A., Decker, M. R., La Marche, A., & Silverman, J. G. (2006). Masculine gender roles associated with increased sexual risk and intimate partner violence perpetration among young adult men. Journal of Urban Health, 83, 575–585.

Shorey, R. C., Cornelius, T. L., & Bell, K. M. (2008). Behavioral theory and dating violence: A framework for prevention programming. The Journal of Behavior Analysis of Offender and Victim Treatment and Prevention, 1, 1.

Silverman, J. G., Raj, A., Mucci, L. A., & Hathaway, J. E. (2001). Dating violence against adolescent girls and associated substance use, unhealthy weight control, sexual risk behavior, pregnancy, and suicidality. JAMA, 286, 572–579.

Sosa-Rubí, S. G., Gertler, P., Romero, M., Rivera-Rivera, L., & Ortiz, E. (2010). Reporte sobre el Programa de Prevención de Violencia en el Noviazgo en Secundarias en Zonas Urbanas. Mimeo. Commissioned by Instituto Mexicano de la Juventud (IMJUVE).

Taylor, B., Stein, N., & Burden, F. (2010). The effects of gender violence/harassment prevention programming in middle schools: A randomized experimental evaluation. Violence and Victimization, 25, 202–223.

Wolfe, D. A., Crooks, C., Jaffe, P., Chiodo, D., Hughes, R., Ellis, W., . . . Donner, A. (2009). A school-based program to prevent adolescent dating violence: A cluster randomized trial. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med, 163, 692–699. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2009.69

Wolfe, D. A., Scott, K., Reitzel-Jaffe, D., Wekerle, C., Grasley, C., & Straatman, A. L. (2001). Development and validation of the conflict in adolescent dating relationships inventory. Psychological Assessment, 13, 277–293.

Wolfe, D. A., Wekerle, C., Scott, K., Straatman, A. L., Grasley, C., & Reitzel-Jaffe, D. (2003). Dating violence prevention with at-risk youth: A controlled outcome evaluation. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71, 279–291.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank the staff at the Colegio de Bachilleres system whose enthusiastic collaboration in all phases of the project made this work possible. In particular, we want to thank Dr. Sylvya B. Ortega Salazar for her leadership and support. We also want to acknowledge staff at ALBANTA for their support with implementing the evaluation, particularly Silvia Conde and Gabriela Conde.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Funding

The data, models, or methodology used in the research are not proprietary. The funding source is the Inter-American Development Bank.

Conflict of Interest

CP works at the IADB and she oversaw the funding of the intervention. The opinions expressed in the paper do not reflect the views of any of the funding or the other organizations that supported and facilitated this study. The funding organizations did not have any role in the study design; data collection, analysis, or interpretation; nor in the writing of the manuscript or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The authors are solely responsible for the contents. They declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval

The CB system administrators and faculty implemented the intervention. They were in charge of implementing the study, assigning groups, and collecting data following their own standards of voluntary participation in surveys. It was clear at all times that the information collected was only to be used for aggregated statistical analysis. Researchers involved in the impact evaluation design and data analysis received the anonymous data for secondary analysis.

Informed Consent

The CB school system collected data during the implementation of the program. School faculty responsible for data collection informed the students the objective of the surveys, that their participation was voluntary, and that they could decline to respond to any question at anytime. The questionnaires were self-administered and the faculty had no access to the data and therefore was unable to see if students did not respond to any question. The instructions in the questionnaires also explained the voluntary nature and confidentiality of the data collection tools.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 299 kb)

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sosa-Rubi, S.G., Saavedra-Avendano, B., Piras, C. et al. True Love: Effectiveness of a School-Based Program to Reduce Dating Violence Among Adolescents in Mexico City. Prev Sci 18, 804–817 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0718-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0718-4