Abstract

Political propaganda can reduce citizens’ inclinations to protest by directly influencing their preferences or beliefs about the government. However, given that protest is risky in authoritarian societies and requires collective participation, propaganda can also reduce citizens’ inclination to protest by making them think that other citizens, rather than themselves, may have been influenced by propaganda and are, as a result, unwilling to protest. We test this indirect mechanism of propaganda using a survey experiment with Chinese internet users from diverse backgrounds and find that they do believe propaganda affects other citizens’ support for and beliefs about the government more than their own support and beliefs. Moreover, they believe that propaganda reduces other citizens’ willingness to protest, which in turn reduces their own willingness to protest. Therefore, the power of propaganda may sometimes lie more in the social perceptions and uncertainty it creates than in its direct individual effects.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

How does political propaganda affect citizen behavior, particularly protest, in an authoritarian society? Standard research on this question focuses on how propaganda directly affects individuals’ political preferences or beliefs. For example, most existing studies regard propaganda as persuasion and argue that propaganda works by persuading citizens about the merits of the government or its policies, thereby increasing citizens’ support of the regime and reducing their inclination to dissent (Adena et al. 2015; Cantoni et al. 2017; Gehlbach and Sonin 2014; Guriev and Treisman 2020; Peisakhin and Rozenas 2018; Rozenas and Stukal 2019). Other works treat propaganda as signaling and suggest that propaganda does not necessarily affect individuals’ political support, but instead signals the power and capacity of the government through the act of propaganda itself, thereby intimidating citizens and dampening their inclination to protest (Huang 2015b; Svolik 2012; Wedeen 1999).

Both propaganda as persuasion and propaganda as signaling are direct and individual-based mechanisms. Mass protests, however, are inherently collective actions. Given that protest is risky under an authoritarian regime and that participants of a failed protest are subject to potentially severe punishment, most individuals’ decisions about whether to protest depend not only on their own preferences or beliefs about the government but also on their perceptions of whether or how many other people will turn out to protest, which then determines how likely the protest will be to succeed (Chwe 2003; Egorov et al. 2009; Lohmann 1994). In other words, protest is a game of complementarity in which individuals will be more (less) willing to participate the more (less) likely they think other people will participate (e.g., Gehlbach et al. 2016; Bueno De Mesquita 2010; Edmond 2013). Incorporating the logic of collective protest into theories of propaganda thus introduces an alternative channel by which regimes can manipulate citizen behavior: Even if propaganda does not directly persuade individuals about the merits of government or influence their beliefs about its power and capacity, it can still make them less willing to protest if they believe that propaganda has successfully persuaded or intimidated other people not to protest.

In other words, propaganda can sometimes work not by influencing individuals’ own preferences or beliefs but by making them think that other people’s preferences or beliefs may have been influenced. This mechanism of propaganda hinges on its indirect effect at the collective level rather than its direct effect at the individual level. We build our theory on the “influence of presumed influence” model in communication studies, which argues that the effects of media are often indirect and occur through the channel of presumed media influence on other people (Gunther and Storey 2003; Tal-Or et al. 2009). A closely related idea, the “third-person effect,” which can be considered a special case of the “influence of presumed influence” model, makes an even more specific prediction: Individuals tend to believe that media and communications have a stronger effect on others than on themselves, and then they react to the presumed effect on others (Davison 1983; Perloff 2009; Sun et al. 2008). Curiously, although propaganda is a key motivating example in Davison ’s (1983) original formulation of the third person effect hypothesis, there have been few empirical investigations of propaganda’s indirect effect, especially in the authoritarian setting. Most studies of the influence of presumed influence instead focus on media effects in democratic societies. This study provides such an investigation in the case of contemporary China to enrich theories of political propaganda. In addition, most existing studies under the influence of presumed media influence framework, particularly those on the third-person effect, use surveys and ask people directly how they think media affects themselves and others. In contrast, we experimentally compare propaganda’s presumed effect on others with its actual effect on oneself, and how the former may affect individuals’ participation in protest more than the latter.

Using an online survey experiment featuring real propaganda messages from China’s state media, we find that propaganda exposure has a greater effect on respondents’ beliefs about other citizens’ support for the regime than on their own support for the regime. Propaganda exposure also has a greater effect on the respondents’ beliefs about other citizens’ assessments of the power and stability of the regime than their own assessment. In addition, propaganda reduces the respondents’ beliefs about other people’s willingness to protest, which in turn has a negative effect on their own willingness to protest.

Our findings suggest that, due to the nature of collective protest, authoritarian propaganda can work not (just) by manipulating what individual citizens think about the regime or their own propensity to protest against the regime, but (also) by manipulating the information and perceptions that citizens have about each other, creating social uncertainty. In other words, political authorities can use their vantage point as an agenda setter to create a mirage surrounding propaganda; citizens’ concern that other citizens could have been influenced by propaganda can sometimes be sufficient to deter them from challenging the authorities. Our results are consistent with the classic game-theoretic argument about the critical role of common knowledge in shaping social interactions. They not only provide micro-level empirical support for the ideas of pluralistic ignorance and preference falsification sustaining authoritarian rule (Chwe 2003; Havel 1985; Kuran 1991) but also explicate a specific and critical mechanism for the phenomenon.

The next section lays out our theory and hypotheses. Section 3 explains the experimental design and data. Section 4 presents the results on both the perceptual and behavioral components of the influence of presumed influence of propaganda. The last section discusses our results and concludes.

Influence of the Presumed Influence of Propaganda

Propaganda is the deliberate dissemination of inaccurate, exaggerated, or fabricated information that favors a political cause or player.Footnote 1 Our theoretical framework about authoritarian propaganda posits that it operates on both the individual and collective levels. At the individual level, propaganda can manipulate the preferences of individuals directly, by persuading them about the merits of the regime, its leaders, or its policies and thus increasing their support of the regime; this is the standard theory of propaganda as persuasion (Adena et al. 2015; Cantoni et al. 2017; Gehlbach and Sonin 2014; Guriev and Treisman 2020; Peisakhin and Rozenas 2018; Rozenas and Stukal 2019). At the same time, some propaganda is not persuasive but heavy-handed and even ridiculous, but by demonstrating the state’s ability to command great resources and the organizational capacity to impose such (unpersuasive and unpopular) propaganda messages on the society, the regime can signal its power and capacity in social control, and thus deter the public from challenging it. In other words, instead of shaping individuals’ political preferences, propaganda can work by influencing their beliefs about the power of the state; this is the theory of propaganda as signaling (Huang 2015b, 2018).

At the collective level, regardless of whether propaganda can change individuals’ own support of the regime or beliefs about the regime’s power, it may affect their perceptions of other people’s support for the regime or their beliefs about the regime’s power, since it is possible that other people have been influenced by propaganda. Because a single person’s protest can be easily defeated by the regime, effective protest almost necessarily requires collective participation. In particular, strategic complementarity “characterizes mass protests” (Gehlbach et al. 2016, p. 579); the fewer people who participate in a protest, the less likely it will succeed (Bueno De Mesquita 2010; Chwe 2003; Edmond 2013). Therefore, given the risk and potentially severe negative consequences of participating in a failed protest against an authoritarian government, people will be less likely to protest the less they think other people will participate in protest.Footnote 2 Propaganda can thus reduce citizens’ protest inclination by making them think that other people (may) have been influenced by propaganda (and consequently support the government or believe the government is too powerful to oppose), even if the effect of propaganda on themselves is limited.Footnote 3 Our focus in this study is on this indirect, collective-level effect of propaganda, i.e., the influence of presumed influence of propaganda (IPIP). It is important to note that IPIP does not deny that propaganda can influence individuals directly. It argues, however, that even if there is little individual-level direct effect, propaganda may still work through its indirect effect at the collective level.

We build our theory of IPIP on the “influence of presumed influence” framework of media effects (Gunther and Storey 2003), including the third-person effect hypothesis (Davison 1983), which has been one of the most influential theoretical frameworks in communication studies (Perloff 2009). The influence of presumed influence model has two components. First, people perceive some influence of a message on others, and this presumed influence on others may well be stronger than the message’s perceived effect on themselves (the perceptual component); Second, people react to their perceptions of the message’s influence on others (the behavioral component). In other words, a media message can have indirect influences on individuals’ behavior through their perceptions of its effect on other people.

The literature in communication studies and social psychology has found robust evidence for the perceptual component of the indirect media influence framework across a wide variety of contexts, such as media violence and pornography, advertising, news coverage, and entertainment, as well as across various study designs (e.g., Cohen et al. 1988; Mutz 1989; Perloff 1999; Peiser and Peter 2000; Price and Tewksbury 1996; Sun et al. 2008). Recent work has extended the research to new areas, such as fake news, polling, social media, and international news, and similarly found that individuals often perceive others to be more influenced than themselves by such messaging and platforms (e.g., Chung et al. 2017; Jang and Kim 2018; Tsay-Vogel 2016; Wei et al. 2017). The literature has examined a variety of explanations for the prevalent self-other perceptual gap: motivational explanations that center on people’s motivations for self-enhancement and the feeling that they are better and less gullible than others, and cognitive explanations in which people act as naive social scientists and create simple theories about the effects of media on society (see Tal-Or et al. 2009, for a review of the literature). Regardless of the specific sources of self-other perceptual gaps, it should be emphasized that the existence of the perceptual component of the presumed media influence model enjoys robust empirical support. This study does not consider the cognitive or psychological sources of the perception that media and communications may have stronger effects on others than oneself, only that the effect can exist in some form and be exploited by propaganda.

Drawing on individual-level theories of propaganda and the perceptual component of the influence of presumed influence framework, we offer two hypotheses about the presumed influence of propaganda. Given that propaganda is traditionally understood as efforts by regimes to increase citizen support through persuasion, our first hypothesis (H1) is that individuals believe that propaganda would increase other people’s support of the regime; in fact, propaganda’s presumed influence on others’ support for the regime will be stronger than its effects on one’s own support for the regime. Note that here we compare individuals’ perceptions of propaganda’s effect on others with its actual effect on oneself. In the traditional third-person effect literature, the comparison is between individuals’ perceptions of media’s effects on others and their perceptions of media’s effects on themselves (but see Cohen et al. 1988). Since people’s perceptions of media’s effects on themselves may not be accurate, it is more useful to use the actual effect as a comparison. This difference will be reflected in our research design, to be discussed in the next section.

Our second hypothesis (H2) is based on the more recent literature on propaganda as signaling, and it posits that propaganda will make individuals believe that propaganda would increase other people’s assessment of the regime’s power and capacity to maintain social stability; in fact, propaganda’s presumed influence on others’ assessment of the regime’s capacity to maintain stability will be stronger than its effect on their own assessment of the regime’s capacity. Note again, here we are comparing individuals’ perceptions of propaganda’s effect on others with its actual effect on themselves.

Our third and perhaps most important hypothesis is about the behavioral effects of propaganda’s presumed influence. While earlier research in the third-person effect literature using the self-other perceptual gap to predict individuals’ behavior has yielded mixed results (Perloff 1999; Xu and Gonzenbach 2008), the influence of presumed influence model emphasizes media’s presumed influence on others rather than perceptual differences between self and others (Gunther and Storey 2003),Footnote 4 and here the evidence has been considerably stronger (Chung and Moon 2016; Dohle et al. 2017; Tal-Or et al. 2009; Wei et al. 2017). But existing research on the influence of presumed media influence has focused on individuals’ support for censorship and restrictions of media content that are perceived to have a negative influence on others, e.g., hate speech, fake news, and pornography. Even in other contexts, such as voting and online political discussion, the behavioral consequence of the third-person effect is usually thought to be that individuals take actions to correct or balance the perceived negative effect of media messaging on others (Golan et al. 2008; Rojas 2010).

We study the effect of the presumed influence of propaganda on collective protest in the authoritarian setting, where the consequence of government messaging is that individuals may take actions to conform to the expected behavior of others who are thought to have been influenced by the messaging rather than to counterbalance the effect of the messaging on others. In addition, dealing with collective action rather than individual behavior, our focus is not just on how the presumed influence of propaganda on other people’s attitudes affects individuals’ behavior, as is commonly the case in existing studies of the influence of presumed influence and third-person effects, but on how the expected behavior of other people, due to propaganda, affects individuals’ own behavior. In other words, given the complementarity of protest behavior, we focus on how propaganda affects individuals’ coordination motives rather than their correction or counterbalance motives (Little 2017; Tal-Or et al. 2009).

We therefore hypothesize that propaganda exposure will create the expectation that propaganda has made other citizens less willing to protest (H3a), and this expectation will negatively affect individuals’ own willingness to protest (H3b). In other words, we propose an indirect channel through which propaganda reduces protest: by affecting how individuals perceive their peers’ willingness to protest, thereby inhibiting their own willingness to participate in collective action. Here, perceptions of other citizens’ willingness to protest serves as a mediating variable between propaganda exposure and individuals’ willingness to protest.

Our analysis of the behavioral effect of the presumed influence of propaganda is related to a few recent studies of media effects. Jin et al. (2018) study how blog posts about the Fukushima nuclear accident’s contamination risks affected people’s seafood consumption behavior and their perceptions of others’ behavior, and how their own behavior and others’ behavior affected each other. Similarly, Tewksbury et al. (2004) study how anxieties about the Y2K computer problem and perceptions of other people’s overreactions to it (e.g., bank withdrawals and food hoarding) influenced individuals’ own protective behavior. These studies, however, do not explain the theoretical foundations of the interaction between self-behavior and other-behavior, e.g., why in the individualistic consumption (as opposed collective action) setting, after controlling for anxiety levels, people would reduce eating seafood in response to other people’s reduced seafood consumption, or why other people’s over-hoarding of cash and food would reduce one’s own protective behavior. Little (2017) provides a game-theoretic model in which some citizens are credulous, and informed citizens who know the government is lying would nevertheless behave as if they believe its propaganda since they want to coordinate their behavior with credulous citizens. The coordination motive is also essential in our collective protest setting, but, in our setting, citizens can be homogeneous (and all disbelieve propaganda) rather than having divergent information capacity.

Our theory is consistent with the classic formal-theoretic literature about the crucial roles of common knowledge, preference falsification, and pluralistic ignorance in affecting regime stability. Propaganda breaks down public communications, without which it will be hard to form common knowledge about citizens’ political attitudes (Chwe 2003). More specifically, in accordance with Kuran ’s (1991) account of preference falsification, propaganda (together with repression) makes citizens hide their true and private preferences and leads to a public discourse that prevents citizens from knowing the real distribution of anti-government sentiments in the society (see also Havel 1985). Such pluralistic ignorance is the wellspring of authoritarian stability. In the more recent global game literature, Edmond (2013) has shown that even though citizens are aware of propaganda, they cannot completely discount the government’s exaggeration of its strength when neither the government’s actual level of strength nor the amount of propaganda is perfectly observed. Further, since citizen actions are strategic complements, information manipulation will reduce every citizens’ incentive to participate in anti-government collective actions if it reduces some citizens’ incentive. Our study provides micro-level empirical evidence in support of these theoretical insights and explicates a specific and critical mechanism, the influence of the presumed influence of propaganda, which leads to preference falsification, pluralistic ignorance, and the breakdown of common knowledge.

Study Design and Data

Study Design

To test the above hypotheses, we conducted a survey experiment in July-August 2018 with 895 Chinese internet users from diverse backgrounds (see more below). The experiment proceeded as follows. Participants were first asked a battery of background questions about their social and political attitudes, including life satisfaction, national pride, political interest, pro-Western orientation, and evaluation of China’s current political system. See Online Appendix 1 for question wording. They were then randomly assigned into one of five groups: a control group that did not receive any propaganda treatment and four treatment groups that each received a different propaganda message (see below). The experiment was designed to compare individuals who were exposed to propaganda with individuals who were not. We use four different propaganda treatments simply because there exists a wide variety of propaganda, and we do not want to unnecessarily limit our analysis to a particular message.

Afterwards, all respondents were asked two sets of outcome questions, the first about their own opinions about China’s current overall current situation, China’s future prospects, the government’s ability in governing the country, its responsiveness to citizen demands, its ability to maintain social and political stability, and, finally, their willingness to participate in protest against government malfeasance and injustice in their region. Due to the political sensitivity of the last question, we used the term “collective walk,” a widely understood codeword on the Chinese internet, to refer to protest.

The questions on China’s overall current situation, the Chinese government’s governance, its responsiveness, and China’s future prospects were all intended to measure respondents’ support for the government, so they were summed into an aggregate variable regime support to avoid the issue of multiple hypothesis testing.Footnote 5 The question on the Chinese government’s ability to maintain stability was intended to measure its perceived power and capacity, in light of the signaling theory of propaganda. The last question on “collective walk” simply measures willingness to protest.Footnote 6

The second set of outcome questions asked the respondents how they thought an average person (“yiban ren”) in the society would answer the above questions if they had been exposed to the same materials during the survey. (For the control group, participants were simply asked how they thought an average person would answer the questions they had just answered). For example, in the first set of questions, respondents were asked about their willingness to protest, and, in the second set, respondents were asked what they believed an average citizen’s willingness to protest was. To avoid priming, the set of questions on the respondents’ own attitudes and beliefs was asked before any questions on their perceptions of other people’s attitudes and beliefs began. Finally, demographic information was collected.

Given the between-subject experimental design, in the analysis below we will compare answers to the self questions between the treatment and control groups to obtain the “self effect” of propaganda (see Cohen et al. 1988, for a similar approach). This is the actual effect of propaganda on oneself rather than its perceived effect on oneself. We will also compare answers to the other questions between the treatment and control groups to obtain the “other effect” of propaganda. This is the presumed effect of propaganda on others. Naturally, individuals do not know the actual effect of propaganda on others, and therefore we measure their perceptions of propaganda’s effect on others. To examine the potentially different effects of propaganda on individuals’ self attitudes and their perceptions of other people’s attitudes, we will compare the differences between answers to the self and other questions in the treatment groups and the differences in the control group, in addition to comparing the self and other effects of propaganda.

This approach differs from how most existing studies measure the self-other perceptual differences. Existing studies typically use surveys, and respondents are directly asked how they think a particular media message would respectively affect themselves and others. But people might not have an accurate perception of a message’s effect on themselves; for example, they sometimes under-report the amount of actual change in their own opinions produced by media messages (Chung et al. 2017). In addition, direct questioning may have a social desirability problem. Indeed, studies have shown that messages viewed as socially desirable often elicit a first-person effect: Respondents state that the positive messages have greater effects on themselves than on others (e.g., Duck et al. 1995; Gunther and Thorson 1992). The social desirability problem may be particularly acute in an authoritarian country, where it is undesirable and even risky to directly reveal the lack of effect of government messages—on themselves or others. Similarly, people’s reports of their own level of support for the regime cannot be taken at face value. Indeed, some recent studies on Chinese public opinion have shown that people often misrepresent their true opinions on politically sensitive questions when asked directly (Jiang and Yang 2016; Li et al. 2018). Our approach did not ask respondents directly how they think propaganda affected themselves or others; rather, it measures propaganda’s effects indirectly and unobtrusively through inter-group comparisons of political attitudes and perceptions. Similarly, when analyzing self-other differences in political attitudes, we do not focus on within-subject differences, since either self attitudes or other attitudes (but particularly the former) may be misrepresented. Instead, we focus on the inter-group differences in the self-other differences.

The four treatments were selected to cover the breadth of state media propaganda in contemporary China. The first treatment was a short and artistically appealing video, titled “China in One Minute,” made by China’s premier official newspaper People’s Daily, that describes the country’s recent economic and social achievements (video treatment).Footnote 7 The second treatment was an article from Global Times, titled “China is just generous. They should all feel ashamed,” which lauds the achievements of China’s space program and its willingness to share the use of China’s planned space station with foreign countries, in contrast to some other countries’ refusal to allow China to participate in the International Space Station project, with some vivid examples (space treatment).Footnote 8 The third treatment was an article from the Seeking Truth magazine, titled “China is the world’s largest democracy,” which argues that China actually has a democratic system and is the world’s largest democracy due to its population (democracy treatment).Footnote 9 The final treatment was an article from the People’s Daily titled “The Whole World is Reading this Book: Xi Jinping on Governance in China,” which touts the alleged popularity of said book around the world (book treatment).Footnote 10 Again, it is important to note that we are not interested in comparing the effects of different treatments; rather, our goal is to understand the differences between the treatment and the control conditions.

Data

The participants in the experiment were recruited through a market survey company, with each unique user and IP address allowed only once in a survey to prevent repetitive participation. The respondents were directed to a US-based survey website to take the survey anonymously, which also allowed us to maintain full control over the survey, and the survey company did not have access to the data. There are several reasons why conducting the survey experiment with an online sample is appropriate for this study. First, online anonymity can make the respondents more truthful with their answers than face-to-face or telephone surveys, which is crucial here, given the sensitivity of our survey questions. Second, over half of China’s population are now online, and the internet has become the center of activism and collective action in the country, with the middle class broadly preferring digital forms of engagement over traditional forms of political participation (Huang 2015a; Yang 2009). Understanding the internet population’s political attitudes and potential behavior is therefore particularly important. As shown in Online Appendix 1, the participants had diverse sociodemographic backgrounds: They came from all walks of life, from various education backgrounds and age groups, and from all over China. In fact, their gender, regional, urban/rural, and occupational distributions are broadly comparable to China’s general internet population. They were younger and better educated on average than the general population, but such characteristics may also be particularly important for our topic: protest.

Table 1 shows the summary statistics of the independent and dependent variables across the experimental groups. With regards to the pre-treatment independent variables, all the demographic variables are balanced across the groups. Most of the pre-treatment dispositional variables are also well balanced, with national pride being the main exception. In the statistical regressions below, we control the demographic and other pre-treatment covariates.

As for the dependent variables, Table 1 indicates that there are no significant differences in the mean values of the self variables between the groups, but there are significant differences in the mean values of the other regime support and other stability. This is mainly driven by the differences between the self variables and other variables in the control group, as their differences in the treatment groups are much smaller. For example, the difference between self regime support and other regime support in the control group is about 0.27 on a five-point scale (\(p<0.001\)), but they are at most around 0.1 in the treatment groups (specifically, in the case of the democracy group, \(p=0.009\)). Essentially, it appears the treatments increased the values of the other variables, without similarly increasingly the values of the self variables.Footnote 11 The next section will take a closer look into the differences.

Analysis and Results

Presumed Influence of Propaganda

We first report the results about propaganda’s effects on individuals’ preferences and beliefs about the government, their perceptions of propaganda’s effects on other people’s preferences and beliefs, and the self-other differences. Figure 1 plots the effects of the treatments on regime support, with and without controlling for demographic and attitudinal covariates (see Tables S2 and S3 in Online Appendix for numerical regression results). The left panel of Fig. 1 shows that, without controlling for the covariates, only the treatment about Xi Jinping’s book significantly increased the respondents’ self regime support relative to the control condition, while the other three treatments did not change self regime support. When the covariates are controlled, all four treatments increased the respondents’ self regime support. Using the omnibus variable “TREATED,” which indicates whether a respondent received any treatment, the effect size of the treatments on self regime support was 3.9 percentage points (with covariates controlled, see Table S2). The middle panel of Fig. 1 shows that, whether controlling for the covariates or not, all four treatments significantly increased the respondents’ perceptions of other people’s regime support. The effect size of the TREATED variable for other regime support when the covariates are controlled was 9.2 percentage points, more than twice as large as the effect size for self regime support.

This suggests the treatments had a significantly greater effect on the respondents’ assessment of other people’s regime support than on their own regime support. The right panel of Fig. 1 shows this is indeed the case. Here the estimand is the difference between the respondents’ perceptions of other people’s regime support and their own regime support. The panel shows that the other-self discrepancies are significantly larger in all treatment groups except the democracy group than in the control group. In other words, not only did the respondents believe propaganda increased other people’s support for the regime, but the messages had a stronger effect on their perceptions of other citizens’ regime support than on their own support, consistent with H1.

Treatment effects on regime support. These are regression coefficients of the treatments, showing their effects on the respondents’ own regime support (left), their perceptions of other people’s regime support (middle), and the differences between their perceptions of other people’s regime support and their own regime support (right). “TREATED” represents a separate model where all treatment groups were pooled as the “treated” group. Regime support is re-scaled to range from 0 to 1. The horizontal lines represent 95% confidence intervals

Figure 2 plots the effects of the treatments on the respondents’ assessment of regime stability (see Tables S4 and S5 in Online Appendix for numerical regression results). The left panel shows that, none of the four propaganda treatments increased the respondents’ own assessment of regime stability relative to the control condition, whether controlling for the covariates or not. The middle panel, on the other hand, shows that all four propaganda messages increased their perceptions of other people’s assessment of regime stability. The effect size of the omnibus TREATED variable for other regime stability is 6.7 percentage points. This suggests that propaganda has stronger effects on the respondents’ perceptions of other people’s assessment of regime stability than on their own assessment of regime stability. The right panel of Fig. 2 shows that this is indeed the case. Here the estimand is the difference between the respondents’ perceptions of other people’s assessment of regime stability and their own assessment of regime stability. The panel shows that the other-self discrepancies are larger in all treatment groups except the democracy group, where the difference misses the .05 significance level, than in the control group. This is because propaganda increased the respondents’ perceptions of other people’s assessment of regime stability without similarly increasing their own assessment of regime stability. The results are consistent with H2.

Treatment effects on assessment of regime stability. These are regression coefficients of the treatments, showing their effects on the respondents’ own assessment of regime stability (left), their perceptions of other people’s assessment of regime stability (middle), and the differences between their perceptions of other people’s assessment of regime stability and their own assessment of regime stability (right). “TREATED” represents a separate model where all treatment groups were pooled as the “treated” group. Assessment of regime stability is re-scaled to range from 0 to 1. The horizontal lines represent 95% confidence intervals

To further test the difference between the treatments’ effects on self attitudes and on other attitudes, we conduct coefficient equality tests for regime support and assessment of regime stability using seemingly unrelated regressions (SUR), which estimate self attitudes and other attitudes as a system of equations and allow the errors in different equations to be correlated. The top panel of Table 2 shows that except for the democracy treatment, the coefficients of all other treatments as well as the omnibus TREATED variable are larger for other regime support than for self regime support. The bottom panel shows that the coefficients of all treatments are larger for other regime stability than for self regime stability, although the difference is only significant at .1 percent level for the democracy treatment. The results are consistent with Figs. 1 and 2 and once more indicate that propaganda has differential effects on the respondents’ own regime support and assessment of regime stability than on their perceptions of others.

The results above lend strong support to both H1 and H2. Propaganda makes the respondents perceive that other people are now more supportive of the regime and that the regime’s ability to maintain stability is now stronger in other people’s assessment. This presumed influence on other peoples’ regime support and assessment of regime stability is stronger than propaganda’s influence on the respondents’ own regime support and assessment of regime stability.

One potential concern about our results is that since our sample is not representative of Chinese society, when the respondents answered questions about what an average person (“yiban ren”) in the society would think about the government, they might have in mind someone different from themselves. In particular, the average person in the society may be less well educated and have lower income than our sample. Indeed, while most of the self-other perceptual gaps in the third person effect literature can be interpreted as biases, Shen et al. (2018) argue that some self-other perceptual gaps may reflect accurate differences, rather than biases, because the individuals in question are comparing themselves to a different group of people.

One way to address the issue is to recognize that because people tend to interact more with and live among people who are like themselves, they tend to overestimate their own representativeness in the population. As a result, when they think about “an average person in the society,” the person they have in mind would be more similar to themselves than an actual average person in the society. In that sense, what the actual average person is like is not as crucial as people’s perception of what an average person is like.

Nevertheless, to mitigate the concern that our respondents might be thinking about people very different from themselves in demographic characteristics when answering questions about the “average person,” we divided the participants into those with college education and those without, and those with high income and those with low income (based on the median values). We then interact the treatments with both education and income, and regress the outcome variables on the interaction terms. As Tables S8–S11 in Online Appendix show, the coefficients of the interaction terms were never statistically significant, meaning that the college-educated did not react to the treatments differently from the non-college-educated, and that the high-income people did not react to the treatments differently from the low-income people, with regards to either self attitudes or perceptions of other attitudes. This suggests that responses to the “average person” questions were not affected by the lack of representativeness of the online sample.

Behavioral Effects of Propaganda’s Presumed Influence

We now examine propaganda’s effect on individuals’ willingness to protest, their perceptions of other citizens’ willingness to protest, and how the latter may affect the former.Footnote 12 Corresponding to Figs. 1, 2, and 3 plots the effects of the treatments on the respondents’ own willingness to protest and their perceptions of others’ willingness to protest (see Tables S6 and S7 for numerical regression results). The left and middle panels show that the propaganda treatments did not affect the respondents’ willingness to protest relative to the control condition, but they did reduce their perceptions of other people’s willingness to protest, which is natural, given propaganda’s presumed influence on other people’s regime support and assessment of regime stability, and consistent with H3a. The right panel of Fig. 3 and the coefficient equality tests in Table 3 indicate that the treatments indeed have differential effects on self protest willingness and other protest willingness.

Treatment effects on willingness to protest. These are regression coefficients of the treatments, showing their effects on the respondents’ willingness to protest (left), their perceptions of other people’s willingness to protest (middle), and the differences between other people’s presumed willingness to protest and the respondents’ own willingness to protest (right). “TREATED” represents a separate model where all treatment groups were pooled as the “treated” group. Willingness to support is re-scaled to range from 0 to 1. The horizontal lines represent 95% confidence intervals

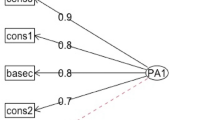

While the above result confirms H3a, it does not address a critical part of our third hypothesis, namely whether individuals’ perceptions of other citizens’ willingness to protest would affect their own willingness to protest (H3b). In particular, the null total effects of propaganda on the respondents’ self protest willingness, shown in Fig. 3, is a combination of the direct effect of propaganda on their own protest willingness and the indirect effect of propaganda on their willingness to protest through its impact on other citizens’ presumed willingness to protest (the mediator), as illustrated in Fig. 4. We need to separate the two effects to understand how changes in other people’s presumed willingness to protest affect individuals’ own willingness to protest.

Therefore, to test H3b and unpack the indirect effect of propaganda on individuals’ protest willingness through its effect on their perceptions of other people’s protest willingness, we employ mediation analysis (Imai et al. 2010, 2011). This method separates the average treatment effect (total effect) into two components: the Average Causal Mediation Effect (ACME) and the Average Direct Effect (ADE). The former represents the indirect effect of the treatment on the outcome through the mediator, while the latter represents the direct effect of the treatment on the outcome with no mediator. The method is intended to ascertain if the treatment explains any variation in the mediator and if that variation in turn explains any variation in the outcome.

Our mediation model has propaganda exposure as the treatment, individuals’ perceptions of other people’s protest willingness as the mediator, and individuals’ own protest willingness as the outcome. Table 4 presents the results of the mediation analysis. The ACMEs of the Video, Democracy, Book, and Space propaganda treatments as well as the omnibus TREATED variable are all negative and significant. This provides strong evidence that propaganda exposure indirectly reduces individuals’ protest willingness by reducing their perceptions of others’ protest willingness, as stated in H3b. The ADEs of the Video and Democracy treatments cannot be distinguished from zero, but interestingly the Book and Space treatments have positive direct effects on protest willingness, suggesting that propaganda messages may sometimes unwittingly cause citizens to want to protest, a kind of backfire effect. In our experiment, this is perhaps because the propaganda messages about the greatness of China and its leader encourage the respondents to express willingness to dissent against injustice and government malfeasance, which are holding China back.Footnote 13 But regardless of propaganda’s direct effect, people’s concern about other citizens’ interpretation of and reactions to propaganda pulled them back and reduced their desire to protest to the null condition, as reflected in the insignificant total effect of propaganda on protest willingness.

The finding of the mediation model does come with one important caveat, however. As Imai et al. (2011) show, use of a mediation model to infer causality must satisfy one key assumption: sequential ignorability. This assumption has two components. First, given the observed pre− treatment confounders, the treatment assignment is statistically independent of potential outcomes and potential mediators. In other words, we are assuming that there are no omitted variables confounding the relationship between the treatment and the mediator and the relationship between the treatment and the outcome. This first component of the assumption holds because treatment assignment is randomized. Second, the observed mediator is ignorable given the actual treatment status and pre-treatment confounders. This essentially translates to assuming that there are no unmeasured pre-treatment or post-treatment covariates that confound the relationship between the mediator and outcome. It is this latter component of the mediation model that potentially poses a threat to our inference.

Recall that the survey experiment first exposed participants to propaganda messages, then asked them about their own willingness to protest, and later asked them about their perceptions of others’ willingness to protest. Because the outcome is measured before the mediator, this raises the potential that a question ordering effect is creating endogeneity between the outcome and mediator. In other words, it could be the case that a correlation between self protest and other protest is a causal effect of the former on the latter via a priming effect. However, in our survey, the question measuring the respondents’ own willingness to protest (self protest) did not immediately precede the question measuring their perceptions of other people’s willingness to protest (other protest). The set of questions on the respondent’s own attitudes and behavior was asked before the set of questions on others began, so there was considerable space between the questions measuring self protest and other protest. Therefore, any question ordering effects are likely to be minimal.

Nevertheless, to offer evidence about the appropriateness of the mediation analysis, we conduct a sensitivity analysis and analyze additional, re-specified, mediation models. Figure 5 presents the sensitivity analysis for the mediation models of Table 4. The sensitivity analysis tests for the degree to which the confidence interval for an indirect effect is sensitive to the correlation between the residuals of the mediator and outcome regressions, which is defined as \(\rho\). In other words, this test estimates the degree of correlation between these two sets of residuals that is necessary to make the confidence interval around the indirect effect contain zero. In effect, this tests for how sensitive the ACME is to a confounding variable. For our models, the sensitivity analysis estimates a \(\rho\) of approximately 0.6, which indicates that the estimates of our mediation model are relatively robust to the presence of a potential confounding variable.

For further robustness, we estimated additional mediation models, but this time the mediating and outcome variables were swapped. If it is indeed the case that individuals’ own willingness to protest is driving their perceptions of others’ willingness to protest, then it should be the case that the propaganda exposure explains some variation in self willingness to protest, and that variation in turn explains some variation in others’ presumed willingness to protest. However, these alternative models failed to identify a significant ACME. As Table 5 shows, the ACME is consistently indistinguishable from zero for all treatment conditions, suggesting that the variations in self protest that were caused by treatment exposure did not explain the variations in other protest. Additionally, consistent with our earlier finding that treatment exposure caused a reduction in other protest, the ADE and total effect of these alternative mediation models are significantly negative in all cases. These results suggest that the possibility of a confounding priming effect is negligible. Our initial mediation analysis results are therefore fairly robust: Perceptions of others’ reduced willingness to protest due to propaganda would drive down people’s own willingness to protest.

Discussion and Conclusion

This study experimentally shows that people often believe that propaganda increases other people’s support for a regime or their beliefs about a regime’s capacity to maintain stability. In fact, the presumed influence of propaganda on other people’s support for and beliefs about a regime are usually stronger than propaganda’s actual influence on oneself. Consequently, propaganda can reduce people’s perceptions of other people’s willingness to protest, which in turn dilutes their own propensity to protest due to its risky nature under authoritarian regimes. Thus, propaganda can stave off dissent not by directly changing individuals’ own attitudes and intentions but, instead indirectly, by altering people’s perceptions of other people’s attitudes and behavioral intentions.

These findings imply that, due to the complementarity of participation in mass protest, authoritarian regimes have a special advantage by being the agenda setters in the propaganda game. Propaganda does not have to directly change individuals’ own willingness to protest to be effective. As long as propaganda reduces individuals’ perceptions of other people’s willingness to protest, or just makes them uncertain if other citizens have been influenced by it, they will be more timid in challenging the regime. Propaganda can achieve much of its function for the regime simply by sowing uncertainty among citizens about what they think others think and will do. Different from what conventional wisdom often assumes, the power of propaganda may sometimes lie more in the social perception and uncertainty it creates than in changes it induces in individuals’ own political attitudes and beliefs.

The study thus enriches theories of authoritarian propaganda, which have so far focused on propaganda’s direct effect on individuals’ themselves. The results also contrast with findings in the existing literature that in democratic and semi-democratic societies, where basic rights of expression and association are guaranteed, stronger perception of other people’s willingness to participate in protest or voting, or perceptions of protest news’s effects on other people, are associated with a lower willingness to participate (Banning 2006; Cantoni et al. 2019; Lo et al. 2017). In these societies, participation is more of a public good that demands a threshold level of contribution: Perception of other people’s participation reduces the need for oneself to participate in order to meet the threshold and, thus, could drive down one’s own willingness to participate. In other words, these are games of substitutes. Collective protests in authoritarian settings, however, are strategic games of complements (Chwe 2003; Edmond 2013; Gehlbach et al. 2016): The more/less willing other people are to participate, the more/less willing are individuals themselves. It is in this strategic setting that propaganda can inhibit people’s willingness to protest by reducing their perceptions of other people’s willingness to protest. And it is this mechanism that contributes to preference falsification, pluralistic ignorance, and the breakdown of common knowledge (Chwe 2003; Havel 1985; Kuran 1991).

Besides enriching our understanding of authoritarian propaganda, this study also contributes to the literature on the influence of presumed media influence. The standard literature on the influence of presumed influence focuses on people’s perceptions of media’s influence on others, without comparing the influence on others with influence on oneself. The third-person effect literature, on the other hand, focus on the discrepancy between media’s presumed influence on oneself and on others, without considering wither the presumed effect on oneself is accurate, or whether the presumed influence of media is really stronger than its actual influence on oneself. We show that propaganda’s presumed effects on others can be stronger than its actual effects on oneself, not just stronger than its presumed effects on oneself. It is this “real” presumed influence of propaganda that leads to one’s perceptions of propaganda’s influence on other people’s behavior, which in turn affects one’s own behavior.

One limitation of the study is that the propaganda messages had negative effects on the respondents’ perceptions of other people’s protest willingness, hence negative indirect effects on their own protest willingness, but the messages had either null or positive direct effects on the respondents’ protest willingness. As discussed above, the positive direct effect is likely because the propaganda messages about the greatness of China and its leader encouraged the respondents to express willingness to dissent against injustice and government malfeasance, which were holding China back. Self-other perceptual discrepancies have always been recognized in the third-person effect literature as a kind of inconsistency or bias. Our study suggests the self-other discrepancies may be larger than typically understood: A media message’s self and other effects may differ not just in magnitude but also in direction. Understanding the causes and/or prevalence of the directional divergence goes beyond the scope of this study, but it is potentially an important issue for future research.

Notes

We focus attention on the typical repressive authoritarian setting rather than on settings where there is a high degree of civil liberty and where punishment for protest participation is traditionally rare, as in Cantoni et al. ’s (2019) study.

The process can even go one step further. Given the complementarity of collective protest, both “all people protest” and “no one protests” are potential equilibria. Propaganda may simply serve as a coordination device and make the “no one protests” outcome the focal point and thus the resulting equilibrium, even if people’s preferences and beliefs about the regime are not influenced by propaganda and they do not think other people are influenced. This possibility can be examined in future research.

Cronbach’s alpha for the index is 0.796, indicating fairly good inter-item reliability. Cronbach’s alpha for the index when measuring the respondents’ perceptions of other people’s support for the government (see below) is even higher: 0.848.

The topics of willingness to protest and the regime’s stability-maintaining capacity were potentially more politically sensitive than other questions. To increase the respondents’ willingness to complete the survey and reduce their wariness, the survey only asked one question for each of the two topics.

The video can be viewed at http://www.chinanews.com/gn/shipin/2018/03-12/news760210.shtml (last accessed December 30, 2020).

See http://world.huanqiu.com/article/2018-05/12116405.html (last accessed December 30, 2020) for the article in Chinese.

See http://www.qstheory.cn/dukan/qs/2017-11/15/c_1121947684.htm (last accessed December 30, 2020) for the article in Chinese.

See http://media.people.com.cn/n1/2018/0129/c40606-29791511.html (last accessed December 30, 2020) for the article in Chinese.

It is also interesting that in the baseline (control) condition, the respondents’ self-reported regime support and assessment of regime stability are higher than their perception of other people’s regime support and assessment of regime stability, and their self-reported willingness to protest is lower than their perception of other people’s protest willingness. However, due to the political desirability of overstating one’s support for the regime and understating willingness to dissent, we do not take this self-reported self-other difference within each group at face value. Instead, we focus on the inter-group differences.

In line with much of the literature on the third-person effect and influence of presumed influence, we use behavioral intentions or attitudes toward behavior to measure behavioral effects.

The result also suggests that the perceived self-other discrepancy in media and propaganda effects may reflect not just magnitude but also direction.

References

Adena, M., Enikolopov, R., Petrova, M., Santarosa, V., & Zhuravskaya, E. (2015). Radio and the Rise of the Nazis in Prewar Germany. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 130(4), 1885–1939.

Banning, S. A. (2006). Third-person effects on political participation. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 83(4), 785–800.

Bueno De Mesquita, E. (2010). Regime change and revolutionary entrepreneurs. American Political Science Review, 104(3), 446–466.

Cantoni, D., Chen, Y., Yang, D. Y., Yuchtman, N., & Zhang, Y. J. (2017). Curriculum and ideology. Journal of Political Economy, 125(2), 338–392.

Cantoni, D., Yang, D. Y., Yuchtman, N., & Zhang, Y. J. (2019). Protests as strategic games: Experimental evidence from Hong Kong’s antiauthoritarian movement. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 134(2), 1021–1077.

Chung, S., Heo, Y.-J., & Moon, J.-H. (2017). Perceived versus actual polling effects: Biases in perceptions of election poll effects on candidate evaluations. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 30(3), 420–442.

Chung, S., & Moon, S.-I. (2016). Is the third-person effect real? A critical examination of rationales, testing methods, and previous findings of the third-person effect on censorship attitudes. Human Communication Research, 42(2), 312–337.

Chwe, M. S.-Y. (2003). Rational ritual: Culture, coordination, and common knowledge. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Cohen, J., Mutz, D., Price, V., & Gunther, A. (1988). Perceived impact of defamation: An experiment on third-person effects. Public Opinion Quarterly, 52(2), 161–173.

Davison, W. P. (1983). The third-person effect in communication. Public Opinion Quarterly, 47(1), 1–15.

Dohle, M., Bernhard, U., & Kelm, O. (2017). Presumed media influences and demands for restrictions: Using panel data to examine the causal direction. Mass Communication and Society, 20(5), 595–613.

Duck, J. M., Terry, D. J., & Hogg, M. A. (1995). The perceived influence of AIDS advertising: Third-person effects in the context of positive media content. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 17(3), 305–325.

Edmond, C. (2013). Information manipulation, coordination, and regime change. Review of Economic Studies, 80(4), 1422–1458.

Egorov, G., Guriev, S., & Sonin, K. (2009). Why resource-poor dictators allow freer media: A theory and evidence from panel data. American Political Science Review, 103(4), 645–668.

Gehlbach, S., & Sonin, K. (2014). Government control of the media. Journal of Public Economics, 118, 163–171.

Gehlbach, S., Sonin, K., & Svolik, M. W. (2016). Formal models of nondemocratic politics. Annual Review of Political Science, 19, 565–584.

Golan, G. J., Banning, S. A., & Lundy, L. (2008). Likelihood to vote, candidate choice, and the third-person effect: Behavioral implications of political advertising in the 2004 Presidential Election. American Behavioral Scientist, 52(2), 278–290.

Gunther, A. C., & Thorson, E. (1992). Perceived persuasive effects of product commercials and public service announcements: Third-person effects in new domains. Communication Research, 19(5), 574–596.

Gunther, A. C., & Storey, J. D. (2003). The influence of presumed influence. Journal of Communication, 53(2), 199–215.

Guriev, S., & Treisman, D. (2020). A theory of informational autocracy. Journal of Public Economics, 186, 104158.

Havel, V. (1985). The power of the powerless: Citizens against the State in Central-Eastern Europe. Armonk: M.E. Sharpe.

Huang, H. (2015a). International knowledge and domestic evaluations in a changing society: The case of China. American Political Science Review, 109(3), 613–634.

Huang, H. (2015b). Propaganda as signaling. Comparative Politics, 47(4), 419–444.

Huang, H. (2018). The pathology of hard propaganda. The Journal of Politics, 80(3), 1034–1038.

Imai, K., Keele, L., & Tingley, D. (2010). A general approach to causal mediation analysis. Psychological Methods, 15(4), 309.

Imai, K., Keele, L., Tingley, D., & Yamamoto, T. (2011). Unpacking the black box of causality: Learning about causal mechanisms from experimental and observational studies. American Political Science Review, 105(4), 765–789.

Jang, S. M., & Kim, J. K. (2018). Third person effects of fake news: Fake news regulation and media literacy interventions. Computers in Human Behavior, 80, 295–302.

Jiang, J., & Yang, D. L. (2016). Lying or believing? Measuring preference falsification from a political purge in China. Comparative Political Studies, 49(5), 600–634.

Jin, B., Chung, S., & Byeon, S. (2018). Media influence on intention for risk-aversive behaviors: The direct and indirect influence of blogs through presumed influence on others. International Journal of Communication, 12, 2443–2460.

Jowett, G. S., & O’Donnell, V. (2018). Propaganda & Persuasion. Newbury Park: Sage Publications.

Kuran, T. (1991). Now out of never: The element of surprise in the East European revolution of 1989. World Politics, 44(1), 7–48.

Li, X., Shi, W., & Zhu, B. (2018). The face of internet recruitment: Evaluating the labor markets of online crowdsourcing platforms in China. Research & Politics, 5(1), 1–8.

Little, A. (2017). Propaganda and credulity. Games and Economic Behavior, 102, 224–232.

Lo, V.-H., Wei, R., & Lu, H.-Y. (2017). Issue importance, third-person effects of protest news, and participation in Taiwan’s sunflower movement. Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly, 94(3), 682–702.

Lohmann, S. (1994). The dynamics of information cascades: The Monday demonstrations in Leipzig, East Germany, 1981–91. World Politics, 47(1), 42–101.

Mutz, D. C. (1989). The influence of perceptions of media influence: Third person effects and the public expression of opinions. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 1(1), 3–23.

Peisakhin, L., & Rozenas, A. (2018). Electoral effects of biased media: Russian television in Ukraine. American Journal of Political Science, 62(3), 535–550.

Peiser, W., & Peter, J. (2000). Third-person perception of television-viewing behavior. Journal of Communication, 50(1), 25–45.

Perloff, R. M. (1999). The third person effect: A critical review and synthesis. Media Psychology, 1(4), 353–378.

Perloff, R. M. (2009). Mass media, social perception, and the third-person effect. In J. Bryant & M. B. Oliver (Eds.), Media effects: Advances in theory and research (3rd ed., pp. 252–268). Abingdon: Routledge.

Price, V., & Tewksbury, D. (1996). Measuring the third-person effect of news: The impact of question order, contrast and knowledge. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 8(2), 120–141.

Rojas, H. (2010). Corrective actions in the public sphere: How perceptions of media and media effects shape political behaviors. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 22(3), 343–363.

Rozenas, A., & Stukal, D. (2019). How autocrats manipulate economic news: Evidence from Russia’s state-controlled television. Journal of Politics, 81, 982–996.

Shen, L., Sun, Y., & Pan, Z. (2018). Not all perceptual gaps were created equal: Explicating the third-person perception (TPP) as a cognitive fallacy. Mass Communication and Society, 21(4), 399–424.

Sun, Y., Pan, Z., & Shen, L. (2008). Understanding the third-person perception: Evidence from a meta-analysis. Journal of Communication, 58(2), 280–300.

Svolik, M. W. (2012). The politics of authoritarian rule. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Tal-Or, N., Tsfati, Y., & Gunther, A. C. (2009). The influence of presumed media influence: Origins and implications of the third-person perception. In R. L. Nabi & M. B. Oliver (Eds.) The SAGE Handbook of Media Processes and Effects. SAGE Publications chapter 7 (pp. 99–112).

Tewksbury, D., Moy, P., & Weis, D. S. (2004). Preparations for Y2K: Revisiting the behavioral component of the third-person effect. Journal of Communication, 54, 138–155.

Tsay-Vogel, M. (2016). Me versus Them: Third-person effects among Facebook users. New Media & Society, 18(9), 1956–1972.

Wedeen, L. (1999). Ambiguities of domination: Politics, rhetoric, and symbols in contemporary Syria. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Wei, R., Lo, V., & Golan, G. (2017). Examining the relationship between presumed influence of US news about China and the support for the Chinese Government’s Global Public relations campaigns. International Journal of Communication, 11, 2964–2981.

Xu, J., & Gonzenbach, W. J. (2008). Does a perceptual discrepancy lead to action? A meta-analysis of the behavioral component of the third-person effect. International Journal of Public Opinion Research, 20(3), 375–385.

Yang, G. (2009). The power of the Internet in China: Citizen activism online. New York: Columbia University Press.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Zhaotian Luo, Arturas Rozenas, Minh Trinh, audience members at APSA and MPSA, and several anonymous reviewers for helpful comments. Replication data are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/ZEYLMH

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Huang, H., Cruz, N. Propaganda, Presumed Influence, and Collective Protest. Polit Behav 44, 1789–1812 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-021-09683-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-021-09683-0