Abstract

Background and aims

We ask how productivity responses of alpine plant communities to increased nutrient availability can be predicted from abiotic regime and initial functional type composition.

Methods

We compared four Caucasian alpine plant communities (lichen heath, Festuca varia grassland, Geranium-Hedysarum meadow, snow bed community) forming a toposequence and contrasting in productivity and dominance structure for biomass responses to experimental fertilization (N, P, NP, Ca) and irrigation for 4–5 years.

Results

The dominant plants in more productive communities monopolized added N and P, at the expense of their neighbors. In three out of four communities, N and P fertilizations gave greater aboveground biomass increase than N or P fertilization alone, indicating overall co-limitation of N and P, with N being most limiting. Relative biomass increase in NP treatment was negatively related to biomass in control plots across the four communities. Grasses often responded more vigorously to P, but sedges to N alone. Finally, we present one of the rare examples of a forb showing a strong N or NP response.

Conclusion

Our findings will help improve our ability to predict community composition and biomass dynamics in cool ecosystems subject to changing nutrient availability as induced by climate or land-use changes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Soil resource regime has a paramount influence on plant community productivity and structure (Grime 1977; Chapin 1980; Tilman 1982; Grime 2001). Plant communities may be assumed to be largely adapted to the current nutrient regime and therefore not to be nutrient limited per se (Körner 2003a).

However, the productivity and abundance of some species or functional groups may increase after nutrient fertilization so those parameters may be considered as nutrient limited. Production of plants in cold regions, i.e. in alpine and arctic communities, is often limited by nitrogen availability, as has been shown in a range of in situ fertilisation studies (e.g. Haag 1974; Shaver et al. 2001; Körner 2003b; van Wijk et al. 2003; Soudzilovskaia et al. 2005; LeBauer and Treseder 2008). Contrary to the well established role of nitrogen limitation, the roles of other nutrients and water limitation for productivity of arctic and alpine communities are not very clear, but can not be dismissed. There is some evidence that phosphorus can limit productivity of alpine communities (Seastedt and Vaccaro 2001), arctic tundra (Chapin 1981; Chapin and Shaver 1989), wetland communities (Gough and Hobbie 2003; Olde Venterink et al. 2003; Gusewell 2004), dry-land communities (Lambers et al. 2008), mountain grasslands on carbonate soils (Sebastia 2007), tropical rainforests (Raaimakers and Lambers 1996; Lambers et al. 2008), but was also shown to be a secondary limiting factor in a Caucasian alpine community (Soudzilovskaia et al. 2005). In some ecosystems raising pH via calcium addition lead to increasing plant biomass production due to a temporary increase of mineralization (De Graaf et al. 1998; Hobbie and Gough 2004). Soil moisture can also be an important factor limiting the production of alpine plant communities (Billings 1974; Walker et al. 1994). Nevertheless, there are few experimental investigations (e.g. Bowman et al. 1995; Soudzilovskaia et al. 2005) testing responses of alpine tundra to water availability manipulations.

Returning to the likely major role of nutrient limitation of production in terrestric ecosystems, two main types of community response to nitrogen or nitrogen-plus-phosphorus fertilizations have been reported repeatedly (Bret-Harte et al. 2008). The first response type features strong increases of graminoid biomass (e.g. Dähler 1992; Jonasson 1992; Press et al. 1998; Gerdol et al. 2000; Graglia et al. 2001; Gough et al. 2002; van Wijk et al. 2003; Bret-Harte et al. 2004; Fremstad et al. 2005; Klanderud 2008) at the apparent expense of dwarf shrubs, mosses, lichens as well as other plants typical for poor soils (e.g. Aerts and Chapin 2000; Cornelissen et al. 2001; van Wijk et al. 2003). The second response type is characterized by herbaceous species (and cryptogams) being replaced by taller woody plants (Tilman 1988; Shaver et al. 2001; van Wijk et al. 2003). However, it is not clear yet (a) which factors drive different communities to the first or second response type, and/or (b) whether alternative response types occur. Here we compare four Caucasian alpine plant communities contrasting in mesorelief position, productivity and dominance structure (Onipchenko 2004) for biomass responses to experimental fertilizations of different mineral nutrients and water. Our primary objectives were to determine: 1) which soil resources limited production of four alpine communities with different mesorelief position, productivity and dominance structure, 2) which plant functional groups react positively or negatively on different nutrient or irrigation; 3) does the response of alpine plant communities to nutrient fertilization or irrigation depend on initial dominance structure, i.e. by the relative abundance of dominant species or functional groups in control plots? To our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive, experimental study on resource limitation of productivity along a toposequence (catena) of alpine communities developing on the same geological substratum.

Methods

Study sites and communities

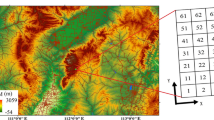

This study was conducted at the Teberda Biosphere Reserve (Northwestern Caucasus, Russia). The experimental site was located on the south and south–east slope of Mt. Malaya Khatipara (43°27′N, 41°41′E at 2700–2800 m a.s.l.). Mean annual temperature in the area is 1.2°C and mean July temperature is 7.9°C (Grishina et al. 1986). Annual precipitation is about 1400 mm. We investigated four alpine communities: alpine lichen heath (hereafter, simply lichen heath), Festuca varia grassland (Festuca grassland), Geranium-Hedysarum meadow (Geranium meadow) and snow bed community (snowbed). This sequence of community types reflects their location along the snow accumulation gradient from snow-free to snow-bed communities. Experimental plots of different communities were situated within a few hundred meters of one another.

Lichen heath occupies windward crests and slopes with little (up to 20–30 cm) or no snow accumulation in the winter. Deep freezing is typical for the soils there. The growing season lasts about 5 months, from May through September. Fruticose lichens are the main dominants (mostly Cetraria islandica (L.) Ach. ). There is no absolute dominant among vascular plants, but the following species contribute more than 5% to aboveground vascular plant biomass: Carex sempervirens, C. umbrosa, Anemone speciosa, Festuca ovina, Antennaria dioica, Trifolium polyphyllum, and Vaccinium vitis-idaea. Total annual primary production is about 150 g m−2 (Onipchenko 2004).

Festuca grasslands are firm-bunch grass communities, which occupy slopes with little snow accumulation (about 0.5–1 m). Snow cover stays until the second half of May or the first half of June, followed by a growing season of about 4 months. Festuca varia and Nardus stricta are the main dominants, together often contributing more than 75% of aboveground biomass. Total annual primary production is about 400 g m−2 (Onipchenko 2004).

Geranium meadow occupies the lower parts of slopes and small depressions with typical snow depths of 2–3 m. It thaws out by the end of June or by early July, followed by a growing season of only 2.5–3.5 months. Geranium gymnocaulon is the main dominant and Nardus stricta, Phleum alpinum, and Hedysarum caucasicum create more than 5% of aboveground biomass. The population density of voles [Pitymys (Microtus) majori Thomas] can reach 940 animals per hectare during a “peak-year” in these communities (Fomin et al. 1989), causing severe disturbances due to their burrowing activity. Voles prefer this community due to taller close plant cover (protecting against birds of prey) and high food plant abundance. The community is, at about 550 g m−2 year−1, the most productive within this alpine toposequence (Onipchenko 2004).

Snowbeds occupy depressions and bottoms of nival and glacial cirques with heavy winter snow accumulation (4 m or more). They have the shortest vegetative season of about 2–2.5 months from mid July until September. Short rosette and dwarf trailing forbs (Sibbaldia procumbens, Minuartia aizoides, Gnaphalium supinum, and Taraxacum stevenii) prevail here. Due to the short growth season the total production is only about 200 g m−2 year−1 (Onipchenko 2004).

Soils (Umbric Leptosols) of the studied communities have silty loam texture. The proportion of sand decreases slightly from lichen heath to snowbed. Alpine soils are relatively poor in available nitrogen and phosphorus, while they are rich in potassium due to the chemical composition of the bedrock (granite and biotitic schist) (Vertelina et al. 1996, Table 1). Soil acidity gradually increases from lichen heath to snowbed (pHH20 ranges from 5.6 in lichen heath soil to 4.7 in snowbed soil – Onipchenko 1994, see also Table 1).

Field methods

The study was conducted during five growing seasons from 1999 through 2003. The experiment included controls and five treatments: Ca addition (in order to raise soil pH), P, N and NP fertilizations and irrigation. Our previous results (Onipchenko 1994) showed that potassium had no influence on plant aboveground production in potassium-rich biotite-derivated soils. Therefore, we did not use K fertilisers in this experiment.

A visually homogeneous area of 19 × 6.5 m was selected for each community and divided into 24 plots. Each plot was 1.5 m × 1.5 m with 1 m buffer zones between plots. The plots were randomly assigned to the treatments, which were replicated four times.

In 1999 Ca, N, P and NP fertilization treatments were started. N, P and NP plots were fertilized annually at the beginning of the growing season, in dry form on the soil surface. Nitrogen was added as urea (9 g N m−2 year−1), phosphorus as double super phosphate (2.5 g P m−2 year−1).

Calcium was added twice: in 1999 as lime and in 2002 as chalk (equivalent amount). The amount of added lime ranged from 52 g m−2 for lichen heath, 84 g m−2 for Festuca grassland, 119 g m−2 for Geranium meadow, to 183 g m−2 for snowbed. Different doses were used because soil acidity differs significantly among the studied communities increasing from the upper (lichen heath) to the lower (snowbed) positions along the catena. The dose of lime or chalk was to neutralize half of the potential acidity of the upper soil horizons, and had been calculated based on published soil properties of the studied communities (Grishina et al. 1993). Irrigation (H2O treatment) was conducted in 1999–2003 during the vegetation period (July–August). The mean daily value of evapotranspiration in the area is about 3 mm (Grishina et al. 1986). Every day the precipitation was measured. If the precipitation over a 3-day period did not compensate for the water loss due to evapotranspiration, the plots were irrigated with 9 mm of water. The total amount of added water varied according to natural precipitation from 0 (2002—wet season) to 45–63 mm (2000—dry season).

In each treatment and each community plot two soil cores (diameter 5.6 cm, depth 10 cm) were sampled for chemical analyses in 2008 (total 8 replications). Soil pH was measured in H2O suspension by a glass electrode (soil to H2O ratio of 1:2.5). Available phosphorus was extracted from soils with 0.5 M CH3COOH at soil to solution ratio of 1:25 and shaking time 1 h. NH +4 –N and NO −3 –N were extracted with 0.05 M K2SO4 at soil to solution ratio of 1:5 and shaking time 1 h. PO 3−4 –P, NH +4 –N and NO −3 –N were determined on a spectrophotometer Genesys-10-UV by colorimetric reactions by the molybdenum-blue, salicylate-nitroprusid and cadmium reduction methods, respectively.

Total above-ground biomass (including both lichens and vascular plants) was sampled in all plots of all treatments in summer 2002 and 2003 during the first half of August, at the peak of the growing season of this relatively late and cold summer. In each plot two 0.25 m × 0.25 m subplots were cut close to the soil surface each year. Thus, there were 16 (8 in 2002 and other 8 in 2003) subplots for each treatment within each community. Vascular plants were sorted by species. Dead leaves of the current season were added to the biomass of the corresponding species; over-wintered dead plant material of all species was considered as litter. Lichens and mosses were not sorted by species. Plant material was air-dried, then oven-dried (90°C, 12 h) and weighed. The three morphologically similar Carex species in lichen heath (Carex umbrosa, C. sempervirens and C. caryophyllea) were pooled as Carex spp.

Seven functional groups were considered: dwarfs shrubs, forbs, hemiparasites, legumes (N-fixers), grasses, sedges and other monocots. Not all of them were represented in all studied communities, so for our analysis we used only groups which had considerable biomass and/or abundance in a community (details in Table 2). We considered grasses and sedges as separate groups instead of general graminoid group due to their different biomass response to fertilization in lichen heath (Soudzilovskaia et al. 2005, 2006).

Data analysis

We analysed the data of total vascular plant aboveground biomass between treatments at final harvest. Data for the subsets of 4-year and 5-year harvests deviated only marginally and non-significantly (data not shown here), so they were pooled for the one way ANOVA. Assumption of normality was tested prior to all statistical tests and logarithmic transformation [log10(x + 1)] applied if necessary. We subsequently applied Tukey post hoc tests. To detect shifts in aboveground biomass composition, functional group fractions (% of aboveground vascular plant biomass) were analysed individually per functional group with one way ANOVA. In order to improve normality the data were transformed by natural logarithm [ln(x + 1)]. We did not run two-way ANOVA for simultaneous analysis of treatment and group effects, because such analysis conducted on percentage data would violate the assumption of independence among functional groups.

To compare high and low productive communities, we considered lichen heath and snowbed as the low-productive and Festuca grassland and Geranium meadow as the highly productive communities. We plotted the mean absolute aboveground biomass increase of each functional group in response to NP treatment (BNP-BContr) against the fraction of the biomass of each functional group relative to total aboveground biomass in the control treatment. Here we used absolute rather than relative biomass increase because only the former would highlight any functional group that would monopolize extra nutrients to outcompete others based on its initial strong contribution to the community. In low-productive communities without clear initial dominance by any functional group we did not expect any functional group to outcompete the others when heavily fertilised. To compare total biomass response between low and high productive communities we used relative biomass increase (BNP-BContr)*100/BContr. All calculations were made with the Statistica 6.0 software package.

Results

Soil nutrient and total biomass response to resource additions

In response to fertilizer application, soil available phosphorus increased consistently in P and NP fertilizations of all communities (Table 1). Availability of inorganic nitrogen increased less strongly, and the difference with the control was not always significant because of high variability in N and NP fertilizations. It is interesting to note that soils of the most productive community (Geranium meadow) in contrast to the other ones did not show a significant increase in N after N or NP fertilization (Table 1).

Since measurements on shoot abundances in the control plots (V.G. Onipchenko et al., unpublished data) indicated that the species abundance (and presumably biomass) structure did not change substantially between the start and end of this study in any of the four communities, we take any differences between different treatments in 2002/2003 to also represent changes relative to initial composition and biomass structure.

Total aboveground biomass significantly increased after NP fertilization in all communities, but there were some differences in response (Fig. 1): it was 156% higher in NP plots relative to control plots for lichen heath, 72% higher for Festuca grassland, 32% higher for Geranium meadow and 110% higher for snowbed. Vascular plants of lichen heath responded positively to N but more to NP treatment, while there were no differences in aboveground biomass between N and NP treatment for Festuca grassland. On the other hand, vascular plant biomass response in the most productive Geranium meadow was significant after NP fertilization only. Interestingly, snowbed showed equal biomass increases in response to NP and Ca treatments. Neither irrigation nor P fertilisation-alone affected aboveground biomass in any of the communities.

Aboveground vascular plant biomass (g m−2) response to experimental treatments for 4-5 growing seasons in four alpine communities: a alpine lichen heath (ALH), b Festuca varia grassland (FVG), c Geranium-Hedysarum meadow (GHM), d snowbed community (SBC). Different letters indicate significant difference among treatments (p < 0.05, post-hoc Turkey test following one-way ANOVA)

The absolute increase in total aboveground biomass upon NP treatment (as compared to the control) ranged from 99.4 g m−2 in Geranium meadow to 118 in snowbed, 165 in Festuca grassland and 197 g m−2 in lichen heath. Thus on average the absolute biomass response of the two low-productive communities (157 g m−2) was not lower, but apparently even somewhat higher, than that of the two highly productive communities (132 g m−2). The productivity of snowbed may be more limited by the short vegetation season than by soil nutrients, which may have influenced our results.

Functional groups and response of dominants

Significant changes in aboveground biomass among treatments were obtained for forbs (increase in NP treatment in comparison with the control), grasses (increase in P and NP), hemiparasites (increase in irrigation and NP fertilization) and sedges (increase in N) in lichen heath, for grasses (increase in N and NP) in Festuca grassland, for forbs (increase in N and NP) and sedges (increase in N) in Geranium meadow and for forbs and grasses (increase in NP) in snowbed (Table 3). Legumes showed marginal response (P = 0.07, increase in P) in Geranium meadow. There were significant changes in functional group fractions in lichen heath (for grasses – increase in P, decrease in N, hemiparasites – increase in fertilization and NP, and sedges – increase in N) and Geranium meadow (for sedges only – decrease in Ca and P). Marginal responses (0.10 > p > 0.05) were noted in Geranium meadow (for legumes, grasses – decrease in NP, and forbs – increase in NP) and in snowbed (for grasses only – increase in NP). Other monocots (OM group) had negligible biomass in all communities and treatments.

Dwarf shrubs and subshrubs (Vaccinium vitis-idaea in lichen heath, Sibbaldia procumbens in Geranium meadow and snowbed) did not react significantly to nutrient or irrigation. Forbs were abundant in all studied communities, but their response to fertilizations and irrigation varied. They did not show significant changes in Festuca grassland, increased their biomass after NP fertilization in lichen heath (2.7-fold in comparison to control) and Geranium meadow (2.1-fold). Nitrogen fertilization significantly increased forb biomass in Geranium meadow (1.5-fold), as well as its percentage in biomass. Ca addition apparently doubled forb biomass in snowbed (Table 3, P = 0.08). Hemiparasites were generally uncommon, but they increased their biomass 20-fold after NP fertilization in lichen heath. Legumes were common in lichen heath and Geranium meadow. They responded marginally (positively) to P, and (negatively) to N and NP fertilizations in Geranium meadow (Table 3). The two main graminoid groups, grasses and sedges, responded very differently to fertilizations. Grasses significantly increased their biomass after NP fertilization in all communities but Geranium meadow. They responded positively to N fertilization in Festuca grassland (mostly owing to Festuca varia) and to P fertilization in lichen heath (mostly owing to F. ovina). In lichen heath the proportion of grasses in aboveground biomass significantly increased in P, significantly decreased in N, but did not change in the NP treatment. In contrast, for the same treatment, the role of grasses marginally decreased in Geranium meadow and marginally increased in snowbed. The biomass of sedges increased most remarkably after N fertilization in lichen heath (5.7-fold) and in Geranium meadow (2.3-fold) (Table 3), also in relative terms.

Across the four communities, there was an overall positive relationship between biomass response of functional groups to NP treatment and the fraction of biomass of these functional groups in control treatments (Fig. 2).

Aboveground biomass response of functional groups to NP fertilisation treatment (4–5 year) in four alpine communities, as a function of the aboveground biomass fraction of each functional group in the control treatment for each community. ALH, Alpine lichen heath; FVG, Festuca varia grassland; GHM, Geranium-Hedysarum meadow; SBC, Snowbed community. F, forbs; G, Grasses. Linear regression relates to all functional groups present in all four communities

Discussion

Which resources limit alpine biomass production?

Our results demonstrate that our four alpine communities differed in which resources limited productivity. For alpine lichen heath (see also Soudzilovskaia et al. 2005) and Geranium-Hedysarum meadow, in which forbs play an important role (see below), nitrogen was the principal and phosphorus the secondary limiting nutrient. Grassland dominated by Festuca varia responded equally to N alone and N combined with P fertilization, thus indicating N limitation only of F. varia in particular (see below). In the snow-bed community aboveground biomass increased equally in NP and Ca treatments, implying co-limitation of N, P and Ca. Possibly greater Ca availability or higher pH promoted nutrient mineralization and thereby reduced N and P limitation (see below). The overall productivity responses to N, P and NP fertilization did not line up with the toposequence and associated snow depth sequence, as N and P colimitation was seen at both ends of the toposequence, with the N limited Festuca varia community in the middle. Altogether, while P and Ca play important roles in specific communities, our results generally support Körner’s (2003b) hypothesis that vascular plant biomass production in alpine communities is mostly nitrogen limited. The same order of production limitation -first N, then P- was also reported for other alpine communities in different mountain areas (Jeffrey and Pigott 1973; Shatvoryan 1978; Molau and Alatalo 1998; Shaver et al. 2001; Heer and Körner 2002).

There are several ecosystems for which P limitation of biomass production has been reported, in many cases from P-depleted old soils after long-term leaching (alpine – Seastedt and Vaccaro 2001; arctic tundra – Chapin 1981; Chapin and Shaver 1989; tropical and subtropical - Walker et al. 1981; Lambers et al. 2008; arctic and temperate wetlands – Gough and Hobbie 2003; Olde Venterink et al. 2003; grasslands on basic soils – Jeffrey and Pigott 1973; Roem et al. 2002). The fact that P was not a main limiting resource in any of our communities may be explained by the relatively high P contents in the soils (1.4–3.3 mg kg−1, Table 1; see also Makarov et al. 1996, 2004), which are only of mid-Holocene age and have therefore been depleted little by substrate weathering (radiocarbon age up to 5000 years, Grishina et al. 1987).

Ca addition lead to doubling of aboveground biomass in snowbed. This unexpected result has no precedent for other alpine communities in the literature. Reduced soil acidity in response to Ca additions can improve nitrogen and phosphorus availability to vascular plants (Rorison 1980). Ca addition, at least temporally, stimulates nitrogen mineralisation (De Graaf et al. 1998; Hobbie and Gough 2004) as well as organic phosphorus mineralisation (Halstead et al. 1963; Islam and Mandal 1977; Condron and Goh 1989; Trasar-Cepeda and Carballas 1991). Indeed, in our experiment we measured an increase in nitrate and mineral phosphorus in snowbed soils, as well as a pH increase from 4.1 in controls to 5.1 after Ca addition (Table 1). Other communities showed a weaker (Festuca grassland, Geranium meadow) or no obvious pH increase (lichen heath).

Irrigation did not influence aboveground biomass in any of our four communities. Similar results were obtained for several arctic and subarctic species and communities (Wookey et al. 1994; 1995; Press et al. 1998; Robinson et al. 1998; Dormann and Woodin 2002; but see Phoenix et al. 2001) and in general for alpine plants, which appear to rarely experience water stress in mesic areas (Welker et al. 2001; Körner 2003b). On the other hand production of several species in mountain meadows in drier regions (Colorado, Alps) show significant water limitation (Bowman and Fisk 2001; Liancourt et al. 2005; Brancaleoni et al. 2007). In our communities, only hemiparasites increased biomass after irrigation treatment. Euphrasia ossica showed a 10-fold increase of population density in irrigated lichen heath plots (Soudzilovskaia and Onipchenko 2005). It seems that seedling establishment of annual hemiparasites strongly depends on soil humidity and Euphrasia is very sensitive to drought (Grubb 1984). However, such annual plants do not play an important role in total community biomass production.

Functional group response to fertilisation

Since most species occurred only in one of the four communities, we cannot be sure that their response to nutrient amendments in one community is representative for the species, as species by soil interactions for fertilization response are possible. At the level of functional types such interactions are also likely to occur, but some general response patterns can still be detected by putting our findings into the broader context based on available results from fertilisation experiments in cool-temperate, alpine and arctic ecosystems in Appendix 1. Phosphorus fertilizations lead to increase in biomass of grasses (especially Festuca ovina) in several studies (Jeffrey and Pigott 1973; Bowman et al. 1993; Soudzilovskaia et al. 2005) including ours. Festuca ovina has very low leaf P concentration in the study area (0.05%—Voronina et al. 1986; 0.022%—Soudzilovskaia et al. 2005; mean for all plant species 0.16%—Voronina et al. 1986) and compared to the global mean of 0.123% (Kattge et al. 2011) and might be limited by this nutrient. Indeed, in a monoculture experiment this species decreased soil P concentration to a greater extent than other species (Onipchenko et al. 2001). However, when P fertiliser was combined with hay cutting in subalpine meadow, the closely related species Festuca varia decreased its abundance with increasing forb biomass (Bush 1940). It is interesting to note the contrasting responses of the two congeneric grasses: production of Festuca varia was limited by N while that of F. ovina. was limited by P. These species differ greatly in traits and corresponding strategies (F. varia – competitor, F. ovina – stress tolerant – Onipchenko et al. 1998). The latter finding suggests that nutrient status and/or nutrient cycling may differ considerably even among species belonging to the same growth form (see also Bombonato et al. 2010).

Legumes, due to their nitrogen fixing ability, often respond positively to P fertilization in temperate grasslands (Rabotnov 1973) as well as in alpine plant communities (Bowman et al. 1993; Theodose and Bowman 1997; Walker et al. 2001). Our results for the Geranium meadow community support these observations. However, Trifolium polyphyllum in lichen heath did not show a significant positive response to P, likely due to the absence of nodulation and N2-fixing activity in this species (Onipchenko 1994).

Graminoids usually increase their abundance after nitrogen treatment in alpine and arctic communities (Appendix 1; McKendrick et al. 1980; Bowman et al. 1993; Press et al. 1998; Theodose and Bowman 1997; Körner 2003b; Calvo et al. 2005). Grasses and sedges can respond differently to N fertilization. Our results for lichen heath and Geranium meadow as well as studies in Colorado (Bowman et al. 1993; Theodose and Bowman 1997; Walker et al. 2001) and Alps (Bassin et al. 2007) demonstrate that sedges respond to nitrogen fertilisation better than grasses. In our monoculture experiments (Onipchenko et al. 2001) sedges (Carex umbrosa, C. sempervirens) effectively decreased available soil nitrogen concentrations. Higher C/N ratios were observed in soils under Cyperaceae (sedge allies) in alpine area (southwestern Alps) in comparison with other communities (Choler 2005). Positive responses of grasses to P fertilization and of sedges to N fertilization were noted in subalpine grasslands in the Pyrenees (Sebastia 2007). Therefore, our results support the view that sedges have a high nitrogen uptake capacity and this group can be strongly limited by low soil nitrogen availability. Thus we recommend to consider sedges and grasses as separate functional groups rather than pooling them as “graminoids”.

One of our key findings is that, while NP fertilization led to significant biomass increases in all four studied communities, different plant functional groups were responsible for this increase. Both grasses and several forbs responded strongly to NP treatment in low productive lichen heath and snowbed, without any species or group monopolizing the extra nutrients for biomass production over a five-year period. In contrast, in the two more productive alpine meadows we observed the most positive response of the main dominant group, i.e. grasses in Festuca grassland and forbs in Geranium meadow. In Geranium meadow this response resulted predominantly from biomass increase of Geranium gymnocaulon, which perhaps may have outcompeted the otherwise potentially responsive grasses there. Based on our literature survey (Appendix 1), this seems to be one of the first records of such strong forb-only biomass response to NP fertilisation in cold-biome communities. Positive responses of forbs on fertilisation were noted in several studies (Madaminov and Budtueva 1990; Henry et al. 1986; Calvo et al. 2005; Bowman et al. 1993; Jägerbrand et al. 2009 – together with temperature increase only), but we obtained an increase in the relative contribution of forbs to aboveground biomass. Otherwise, such dominance of forbs in response to fertilization can also be observed at the patch scale in the agricultural landscape, for instance patches of stinging nettles (Urtica dioica) in cattle resting areas with high dung concentration. So, in contrast to Bret-Harte et al. (2008) we propose that there are now three main types of cold biome community responses to NP fertilizations (see Appendix 1): (1) graminoid increase (Jeffrey and Pigott 1973; Bowman et al. 1993; Theodose and Bowman 1997; Gerdol et al. 2000; Bowman and Fisk 2001; Graglia et al. 2001; Walker et al. 2001; Gerdol et al. 2002; Gough and Hobbie 2003), (2) deciduous shrub increase (Shaver et al. 2001; van Wijk et al. 2003) and (3) dominant forb increase (e.g. our results for Geranium meadow). The second type was not observed in our communities owing possibly to (1) the absence of relatively tall (and deciduous) shrubs in the local species pool; (2) lack of time for shrubs to migrate from other communities. Thus, our data do not exclude the possibility of shrub expansion in response to fertilisation over longer time scales.

Conclusion

Our 4–5 year long in situ fertilisation and irrigation experiment of four alpine plant communities in the NW Caucasus has yielded three main findings which, we believe, have implications for how we think about nutrient limitation of plant communities in cold biomes: (1) We have shown that, in three out of four alpine communities, N and P fertilizations give greater aboveground biomass increases compared to fertilizations with N or P alone, indicating overall co-limitation of N and P, with N being the principal limiting nutrient. Only Festuca varia grassland responded in a way consistent with N limitation alone, while the snow-bed community also increased biomass substantially in response to Ca addition. (2) Where previous studies have generally reported strong dominance of either graminoids or shrubs upon N or NP fertilisation, we have presented the first firm example of a forb showing a similar response. (3) We have shown that the biomass response (mainly increase) of different functional groups to nutrient fertilisation is to an important degree a function of the initial composition of the community. Our findings will together help to improve our ability to predict community composition and biomass dynamics in cool- and cold-climate ecosystems subject to external nutrient inputs, as related for instance to nitrogen deposition from anthropogenic sources (Bobbink et al. 2010).

Abbreviations

- Vorob’eva:

-

and Onipchenko (2001)

References

Aerts R, Chapin FS III (2000) The mineral nutrition of wild plant revisited: a re-evaluation of processes and patterns. Adv Ecol Res 30:1–67

Bassin S, Volk M, Suter M, Buchmann N, Fuhrer J (2007) Nitrogen deposition but not ozone affects productivity and community composition of subalpine grassland after 3 yr of treatment. New Phytol 175:523–534

Billings WD (1974) Arctic and alpine vegetation: plant adaptations to cold summer climates. In: Ives JD, Barry RG (eds) Arctic and alpine environments. Methuen, London, pp 403–443

Bobbink R, Hicks K, Galloway J, Spranger T, Alkemade R, Ashmore M, Bustamante M, Cinderby S, Davidson E, Dentener F, Emmett B, Erisman J-W, Fenn M, Gilliam F, Nordin A, Pardo L, De Vries W (2010) Global assessment of nitrogen deposition effects on terrestrial plant diversity: a synthesis. Ecol Appl 20:30–59

Bombonato L, Siffi C, Gerdol R (2010) Variations in the foliar nutrient content of mire plants: effects of growth-form based grouping and habitat. Plant Ecol 211:235–251

Bowman WD, Fisk MC (2001) Primary production. In: Bowman WD, Seastedt TR (eds) Structure and function of an alpine ecosystem. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 177–197

Bowman WD, Theodose TA, Schardt JC, Conant RT (1993) Constraints of nutrient availability on primary production in two alpine tundra communities. Ecology 74:2085–2097

Bowman WD, Theodose TA, Fisk MS (1995) Physiological and production responses of plant growth forms to increases in limiting resources in alpine tundra: implications for differential community responses to environmental change. Oecologia 101:217–227

Brancaleoni L, Gualmini M, Tomaselli M, Gerdol R (2007) Responses of subalpine dwarf-shrub heath to irrigation and fertilization. J Veg Sci 18:337–344

Bret-Harte MS, Garcia EA, Sacre VM, Whorley JR, Wagner JL, Lippert SC, Chapin FS III (2004) Plant and soil responses to neighbour removal and fertilization in Alaskan tussock tundra. J Ecol 92:635–647

Bret-Harte MS, Mack MC, Goldsmith GR, Sloan DB, DeMarco J, Shaver GR, Ray PM, Biesinger Z, Chapin FS III (2008) Plant functional types do not predict biomass responses to removal and fertilization in Alaskan tussock tundra. J Ecol 96:713–726

Bush EA (1940) On results of scientific researches in South Ossetia mountain meadow station BIN AS USSR. Sov Bot 2:11–29 (in Russian)

Calvo L, Alonso I, Fernandez AJ, De Luis E (2005) Short-term study of effects of fertilisation and cutting treatments on the vegetation dynamics of mountain heathlands in Spain. Plant Ecol 179:181–191

Chapin FS III (1980) The mineral nutrition of wild plants. Annu Rev Ecol Syst 11:233–260

Chapin FS III (1981) Field measurements of growth and phosphate absorption in Carex aquatilis along a latitudinal gradient. Arct Alp Res 13:83–94

Chapin FS III, Shaver GR (1989) Differences in growth and nutrient use among arctic plant growth forms. Funct Ecol 3:73–80

Choler P (2005) Consistent shifts in alpine plant traits along a mesotopographical gradient. Arct Antarct Alp Res 37:444–453

Condron LM, Goh KM (1989) Effects of long-term phosphatic fertilizer applications on amounts and forms of phosphorus in soils under irrigated pasture in New Zealand. J Soil Sci 40:383–395

Cornelissen JHC, Callaghan TV, Alatalo JM, Michelsen A, Graglia E, Hartley AE, Hik DS, Hobbie SE, Press MC, Robinson CH, Henry GHR, Shaver GR, Phoenix GK, Gwynn Jones D, Jonasson S, Chapin FS III, Molau U, Neil C, Lee JA, Melillo JM, Sveinbjornsson B, Aerts R (2001) Global change and arctic ecosystems: is lichen decline a function of increases in vascular plant biomass? J Ecol 89:984–994

Dähler W (1992) Long term influence of fertilization in a Nardetum. Results from the test plots of Dr. W Ludi on the Schynige Platte. Vegetatio 103:141–150

De Graaf MCC, Verbeek PJM, Bobbink R, Roelofs JGM (1998) Restoration of species-rich dry heaths: the importance of appropriate soil conditions. Acta Bot Neerl 47:89–111

Dormann CF, Woodin SJ (2002) Climate change in the Arctic: using plant functional types in a meta-analysis of field experiments. Funct Ecol 16:4–17

Fomin SV, Onipchenko VG, Sennov AV (1989) Feeding and digging activities of the pine vole (Pitymys majori Thos.) in alpine communities of the Northwestern Caucasus. Bull Mosk Obŝ Ispyt Prĭr Otd Biol 94:6–13 (in Russian)

Fremstad E, Paal J, Mols T (2005) Impacts of increased nitrogen supply on Norwegian lichen-rich alpine communities: a 10-year experiment. J Ecol 93:471–481

Gerdol R, Brancaleoni L, Menghini M, Marchesini R (2000) Response of dwarf shrubs to neighbour removal and nutrient addition and their influence on community structure in a subalpine heath. J Ecol 88:256–266

Gerdol R, Brancaleoni L, Marchesini R, Bragazza L (2002) Nutrient and carbon relations in subalpine dwarf shrubs after neighbor removal or fertilization in northern Italy. Oecologia 130:476–483

Gough L, Hobbie SE (2003) Responses of moist non-acidic arctic tundra to altered environment: productivity, biomass, and species richness. Oikos 103:204–216

Gough L, Wookey PA, Shaver GR (2002) Dry heath arctic tundra responses to long-term nutrient and light manipulation. Arct Antarct Alp Res 34:211–218

Graglia E, Jonasson S, Michelsen A, Schmidt IK, Havstrom M, Gustavsson L (2001) Effects of environmental perturbations on abundance of subarctic plants after three, seven and ten years of treatments. Ecography 24:5–12

Grime JP (1977) Evidence for the existence of three primary strategies in plants and its relevance to ecological and evolutionary theory. Am Nat 111:1169–1194

Grime JP (2001) Plant strategies, vegetation processes, and ecosystem properties, 2nd edn. John Wiley, Chichester

Grishina LA, Onipchenko VG, Makarov MI (1986) Composition and structure of alpine heath biogeocoenoses. Izd Mosk Univ, Moscow (in Russian)

Grishina LA, Cherkinskiy AE, Zhakova OE, Onipchenko VG (1987) Radiocarbon age of alpine mountain meadow soils of the Northwestern Caucasus. Dokl Earth Sci Sect 296(5):228–229

Grishina LA, Onipchenko VG, Makarov MI, Vanyasin VA (1993) Changes in properties of mountain-meadow alpine soils of the northwestern Caucasus under different ecological conditions. Euras Soil Sci 25:1–12

Grubb PJ (1984) Some growth points in investigative plant ecology. In: Cooley JS, Golley FG (eds) Trends in ecological research for the 1980s. Plenum Press, New York, pp 51–74

Gusewell S (2004) N:P ratios in terrestrial plants: variation and functional significance. New Phytol 164:243–266

Haag RW (1974) Nutrient limitations to plant production in two tundra communities. Can J Bot 52:103–116

Halstead RL, Lapensee JM, Ivarson KC (1963) Mineralization of soil organic phosphorus with particular reference to the effect of lime. Can J Soil Sci 43:97–106

Heer C, Körner C (2002) High elevation pioneer plants are sensitive to mineral nutrient addition. Basic Appl Ecol 3:39–47

Henry GHR, Freedman B, Svoboda J (1986) Effects of fertilization on three tundra plant-communities of a polar desert oasis. Can J Bot 64:2502–2507

Hobbie SE, Gough L (2004) Litter decomposition in moist acidic and non-acidic tundra with different glacial histories. Oecologia 140:113–124

Islam A, Mandal R (1977) Amounts and mineralization of organic phosphorus compounds and derivatives in some surface soils of Bangladesh. Geoderma 17:57–68

Jägerbrand AK, Alatalo JM, Chrimes D, Molau U (2009) Plant community responses to 5 years of simulated climate change in meadow and heath ecosystems at a subarctic-alpine site. Oecologia 161:601–610

Jeffrey DW, Pigott CD (1973) The response of grasslands on sugar-limestone in Teesdale to application of phosphorus and nitrogen. J Ecol 61:85–92

Jonasson S (1992) Plant response to fertilization and species removal in tundra related to community structure and clonality. Oikos 63:420–429

Kattge J, Diaz S, Lavorel S, Prentice IC, Leadley P, Bönisch G, Garnier E, Westoby M, Reich PB, Wright IJ, Cornelissen JHC, Violle C, Harrison SP, Van Bodegom PM, Reichstein M, Enquist BJ, Soudzilovskaia NA, Ackerly DD, Anand M, Atkin O, Bahn M, Baker TR, Baldocchi D, Bekker R, Blanko CC, Blonder B, Bond WJ, Bradstock R, Bunker DE, Casanoves F, Cavender-Bares J, Chambers JQ, Chapin FS III, Chave J, Coomes D, Cornwell WK, Craine JM, Dobrin BH, Duarte L, Durka W, Elser J, Esser G, Estiarte M, Fagan WF, Fang J, Fernandez-Mendez F, Fidelis A, Finegan B, Flores O, Ford H, Frank D, Freschet GT, Fyllas NM, Gallagher RV, Green WA, Gutierrez AG, Hickler T, Higgins SI, Hodgson JG, Jalili A, Jansen S, Joly CA, Kerkhoff AJ, Kirkup D, Kitajima K, Kleyer M, Klotz S, Knops JMH, Kramer K, Kühn I, Kurokawa H, Laughlin D, Lee T, Leishman M, Lenz F, Lenz T, Lewis SL, Lloyd J, Llusia J, Louault F, Ma S, Mahecha MD, Manning P, Massad T, Medlyn BE, Messier J, Moles AT, Müller SC, Nadrowski K, Naeem S, Niinemets Ü, Nöllert S, Nüske A, Ogaya R, Oleksyn J, Onipchenko VG, Onoda Y, Ordonez J, Overbeck G, Ozinga W, Patino S, Paula S, Pausas JG, Penuelas J, Phillips OL, Pillar V, Poorter H, Poorter L, Poschlod P, Prinzing A, Proulx R, Rammig A, Reinsch S, Reu B, Sack L, Saldago-Negret B, Sardans J, Shiodera S, Shipley B, Siefert A, Sosinski E, Soussana J-F, Swaine E, Swenson N, Thompson K, Thornton P, Waldram M, Weiher E, White M, White S, Wright SJ, Yguel B, Zaehle S, Zanne AE, Wirth C (2011) TRY - a global database of plant traits. Glob Change Biol 17:2905–2935

Klanderud K (2008) Species-specific responses of an alpine plant community under simulated environmental change. J Veg Sci 19:363–372

Körner C (2003a) Limitation and stress – always or never? J Veg Sci 14:141–143

Körner C (2003b) Alpine plant life: functional plant ecology of High Mountain Ecosystems, 2nd edn. Springer Berlin

Lambers H, Raven JA, Shaver GR, Smith SE (2008) Plant nutrient-acquisition strategies change with soil age. Trends Ecol Evol 23:95–103

LeBauer DS, Treseder KK (2008) Nitrogen limitation of net primary productivity in terrestrial ecosystems is globally distributed. Ecology 89:371–379

Liancourt P, Corcket E, Michalet R (2005) Stress tolerance abilities and competitive responses in a watering and fertilization field experiment. J Veg Sci 16:713–722

Madaminov AA, Budtueva TI (1990) Influence of fertilisation and grazing on occurrence of species in alpine plant communities, Gissaric Ridge. Dokl AS Tadž SSR 33:272–275 (in Russian)

Makarov MI, Guggenberger G, Zech W, Alt HG (1996) Organic phosphorus species in humic acids of mountain soils along a toposequence in the Northern Caucasus. J Plant Nutr Soil Sci 159:467–470

Makarov MI, Haumaier L, Zech W, Malysheva TI (2004) Organic phosphorus compounds in particle-size fractions of mountain soils in the northwestern Caucasus. Geoderma 118:101–114

McKendrick JD, Batzli GO, Everett KR, Swansons J (1980) Some effects of mammalian herbivores and fertilization on tundra soils and vegetation. Arct Alp Res 12:565–578

Molau U, Alatalo JM (1998) Responses of subarctic-alpine plant communities to simulated environmental change: biodiversity of bryophytes, lichens, and vascular plants. Ambio 27:322–329

Olde Venterink H, Wassen MJ, Verkroost AWM, De Ruiter PC (2003) Species richness-productivity patterns differ between N-, P-, and K-limited wetlands. Ecology 84:2191–2199

Onipchenko VG (1994) The spatial structure of the alpine lichen heaths (ALH): hypothesis and experiments. Veröff Geobot Inst ETH, Stift Rübel, Zürich 115:100–111

Onipchenko VG (ed) (2004) Alpine ecosystems in the Northwest Caucasus. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht

Onipchenko VG, Semenova GV, van der Maarel E (1998) Population strategies in severe environments: alpine plants in the northwestern Caucasus. J Veg Sci 9:27–40

Onipchenko VG, Makarov MI, van der Maarel E (2001) Influence of alpine plants on soil nutrient concentrations in a monoculture experiment. Folia Geobot 36:225–241

Phoenix GK, Gwynn-Jones D, Callaghan TV, Sleep D, Lee JA (2001) Effects of global change on a sub-Arctic heath: effects of enhanced UV-B radiation and increased summer precipitation. J Ecol 89:256–267

Press MC, Potter JA, Burke MJW, Callaghan TV, Lee JA (1998) Responses of a sub-Arctic dwarf shrub heath community to simulated environmental change. J Ecol 86:315–327

Raaimakers D, Lambers H (1996) Response to phosphorus supply of tropical tree seedlings: a comparison between a pioneer species Tapirira obtusa and a climax species Lecythis corrugate. New Phytol 132:97–102

Rabotnov TA (1973) Influence of mineral fertilisers on meadow plants and plant communities. Nauka, Moscow (in Russian)

Robinson CH, Wookey PA, Lee JA, Callaghan TV, Press MC (1998) Plant community responses to simulated environmental change at a high arctic polar semi-desert. Ecology 79:856–866

Roem WJ, Klees H, Berendse F (2002) Effects of nutrient addition and acidification on plant species diversity and seed germination in heathland. J Appl Ecol 39:937–948

Rorison IH (1980) The effects of soil acidity on nutrient availability and plant response. In: Hutchinson TC, Havas M (eds) The effect of acid precipitation on terrestrial ecosystems. Plenum Press, New York, pp 283–304

Seastedt TR, Vaccaro L (2001) Plant species richness, productivity, and nitrogen and phosphorus limitations across a snowpack gradient in alpine tundra, Colorado, U.S.A. Arct Antarct Alp Res 33:100–106

Sebastia M-T (2007) Plant guilds drive biomass response to global warming and water availability in subalpine grassland. J Appl Ecol 44:158–167

Shatvoryan PB (1978) Influence of Armenian phosphate dust on production of alpine meadows. Izv AS Armen SSR, Earth Sci 31:90–92 (in Russian)

Shaver GR, Bret-Harte MS, Jones MH, Johnstone J, Gough L, Laundre J, Chapin FS III (2001) Species composition interacts with fertilizer to control long-term change in tundra productivity. Ecology 82:3163–3181

Soudzilovskaia NA, Onipchenko VG (2005) Experimental investigation of fertilization and irrigation effects on an alpine heath, northwest Caucasus, Russia. Arct Antarct Alp Res 37:602–610

Soudzilovskaia NA, Onipchenko VG, Cornelissen JHC, Aerts R (2005) Biomass production, N:P ratio and nutrient limitation in a Caucasian alpine tundra plant community. J Veg Sci 16:399–406

Soudzilovskaia NA, Vagin IA, Onipchenko VG (2006) Production of an alpine lichen heath under fertilisation and irrigation: results of 6 years experiment in the Northwest Caucasus. Bull Mosk Obŝ Ispyt Prĭr Otd Biol 111:41–51 (in Russian)

Theodose TA, Bowman WD (1997) Nutrient availability, plant abundance, and species diversity in two alpine tundra communities. Ecology 78:1861–1872

Tilman D (1982) Resource competition and community structure. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Tilman D (1988) Plant strategies and the dynamics and structure of plant communities. Princeton University Press, Princeton

Trasar-Cepeda MC, Carballas T (1991) Liming and the phosphatase activity and mineralization of phosphorus in an Andic soil. Soil Biol Biochem 23:209–215

Van Wijk MT, Clemmensen KE, Shaver GR, Williams M, Callaghan TV, Chapin FS III, Cornelissen JHC, Gough L, Hobbie SE, Jonasson S, Lee JA, Michelsen A, Press MC, Richardson SJ, Rueth H (2003) Long-term ecosystem level experiments at Toolik Lake, Alaska, and at Abisko, Northern Sweden: generalizations and differences in ecosystem and plant type responses to global change. Glob Chang Biol 10:105–123

Vertelina OS, Onipchenko VG, Makarov MI (1996) Primary minerals and weathering processes in high-mountain soils of the Teberda Reserve. Mosc Univ Soil Sci Bull 51:1–8

Vorob’eva FM, Onipchenko VG (2001) Vascular plants of Teberda Reserve. Flora i fauna zapov 99:1–100 (in Russian)

Voronina IN, Onipchenko VG, Ignat’eva OV (1986) Components of the biological cycle in alpine barrens of the Northwestern Caucasus. Sov Soil Sci 18:29–37

Walker BH, Ludwig D, Holling CS, Peterman RM (1981) Stability of semi-arid savanna grazing systems. J Ecol 69:437–498

Walker MD, Webber PJ, Arnold EH, Ebert-May D (1994) Effects of interannual climate variation on aboveground phytomass in alpine vegetation. Ecology 75:393–408

Walker MD, Walker DA, Theodose TA, Webber PJ (2001) The vegetation: hierarchical species-environment relationships. In: Bowman WD, Seastedt TR (eds) Structure and function of an alpine ecosystem: Niwot Ridge, Colorado. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 99–127

Welker JM, Bowman WD, Seastedt TR (2001) Environmental Change and Future Directions in Alpine Research. In: Bowman WD, Seastedt TR (eds) Structure and function of an alpine ecosystem: Niwot Ridge, Colorado. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp 304–322

Wookey PA, Welker JM, Parsons AN, Press MC, Callaghan TV, Lee JA (1994) Differential growth, allocation and photosynthetic responses of Polygonum viviparum to simulated environmental change in a high arctic polar semi-desert. Oikos 70:131–139

Wookey PA, Robinson CH, Parsons AN, Welker JM, Press MC, Callaghan TV, Lee JA (1995) Environmental constraints of the growth, photosynthesis and reproductive development of Dryas octopetala at a high arctic polar semi-desert, Svalbard. Oecologia 102:478–489

Acknowledgements

This investigation was financially supported by grants 047.017.010 and 047.018.003 of the Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) and grants 08-04-00344 and 11-04-01215 of the Russian Foundation for Basic Research. We thank Renato Gerdol and two anonymous reviewers for important suggestions for this paper.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible Editor: Harry Olde Venterink.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

ESM 1

(DOCX 20 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

About this article

Cite this article

Onipchenko, V.G., Makarov, M.I., Akhmetzhanova, A.A. et al. Alpine plant functional group responses to fertiliser addition depend on abiotic regime and community composition. Plant Soil 357, 103–115 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-012-1146-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11104-012-1146-2