Abstract

Key message

Conifers contain P450 enzymes from the CYP79 family that are involved in cyanogenic glycoside biosynthesis.

Abstract

Cyanogenic glycosides are secondary plant compounds that are widespread in the plant kingdom. Their biosynthesis starts with the conversion of aromatic or aliphatic amino acids into their respective aldoximes, catalysed by N-hydroxylating cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYP) of the CYP79 family. While CYP79s are well known in angiosperms, their occurrence in gymnosperms and other plant divisions containing cyanogenic glycoside-producing plants has not been reported so far. We screened the transcriptomes of 72 conifer species to identify putative CYP79 genes in this plant division. From the seven resulting full-length genes, CYP79A118 from European yew (Taxus baccata) was chosen for further characterization. Recombinant CYP79A118 produced in yeast was able to convert l-tyrosine, l-tryptophan, and l-phenylalanine into p-hydroxyphenylacetaldoxime, indole-3-acetaldoxime, and phenylacetaldoxime, respectively. However, the kinetic parameters of the enzyme and transient expression of CYP79A118 in Nicotiana benthamiana indicate that l-tyrosine is the preferred substrate in vivo. Consistent with these findings, taxiphyllin, which is derived from l-tyrosine, was the only cyanogenic glycoside found in the different organs of T. baccata. Taxiphyllin showed highest accumulation in leaves and twigs, moderate accumulation in roots, and only trace accumulation in seeds and the aril. Quantitative real-time PCR revealed that CYP79A118 was expressed in plant organs rich in taxiphyllin. Our data show that CYP79s represent an ancient family of plant P450s that evolved prior to the separation of gymnosperms and angiosperms. CYP79A118 from T. baccata has typical CYP79 properties and its substrate specificity and spatial gene expression pattern suggest that the enzyme contributes to the formation of taxiphyllin in this plant species.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Plants produce a plethora of so called secondary or specialized compounds to defend themselves against a multitude of biotic and abiotic stresses. Many of these compounds are widespread in the plant kingdom while others are specific for a certain plant family or even a single genus or species. Flavonoids and terpenes, for instance, are produced by many plants including angiosperms, gymnosperms, ferns, and mosses (Rausher 2006; Gershenzon and Croteau 1991). In contrast, glucosinolates and benzoxazinoids are only known in angiosperms and are mainly restricted to the Brassicales and Poaceae, respectively (Halkier and Gershenzon 2006; Frey et al. 2009).

Cyanogenic glycosides represent a diverse group of secondary compounds that is widespread in the plant kingdom. So far they have been found in the angiosperms, the conifers, and ferns (Hegenauer 1959; Kofod and Eyjolfsson 1969; Harper et al. 1976; Zagrobelny et al. 2008). Cyanogenic glycosides are derived from aliphatic or aromatic α-hydroxynitriles and are usually stored in the vacuole or other specialized vesicle-like structures (Gleadow and Moller 2014). After tissue disruption caused, for example, by chewing herbivores, cyanogenic glycosides come in contact with β-glucosidases that catalyse the hydrolysis of the β-glycosidic bond between the sugar and the hydroxynitrile moiety. The released α-hydroxynitriles are unstable and can rapidly convert to toxic hydrogen cyanide and highly reactive aldehydes or ketones (recently reviewed in Gleadow and Moller 2014). Cyanogenic glycosides are effective deterrents to generalist herbivores (Gleadow and Woodrow 2002; Zagrobelny et al. 2004) and have been described as defence compounds against pathogens (Osbourn 1996). Moreover, they are discussed as carbon and nitrogen storage and transport forms and as modulators of oxidative stress (Selmar et al. 1988; Moller 2010a).

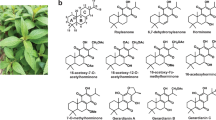

The biosynthesis of cyanogenic glycosides was first elucidated in Sorghum bicolor (McFarlane et al. 1975; Moller and Conn 1979; Halkier et al. 1989) and the enzymes involved have now been identified and characterized in several plant species including sorghum (S. bicolor) (Sibbesen et al. 1995; Bak et al. 1998; Jones et al. 1999), the legume Lotus japonicus (Takos et al. 2011), and cassava (Manihot esculenta) (Andersen et al. 2000; Jorgensen et al. 2011; Kannangara et al. 2011). The first and rate-limiting step of the pathway is catalysed by cytochrome P450 monooxygenases (CYP) of the CYP79 family. CYP79 enzymes accept aromatic and aliphatic amino acids as substrates and convert them into aldoximes by two successive N-hydroxylations, a dehydration and a decarboxylation reaction (Halkier et al. 1995; Sibbesen et al. 1995). The aldoximes formed can be further metabolized by CYP71 or CYP736 enzymes to labile α-hydroxynitriles that are stabilized by rapid glycosylation through the action of family 1 UDP-glycosyltransferases (UGT) (Bak et al. 1998; Jones et al. 1999; Takos et al. 2011; Kannangara et al. 2011).

Although the enzymes involved in cyanogenic glycoside formation have been extensively investigated in the angiosperms, little is known about their occurrence and biological roles in other plant lineages. Multiple conifer species such as European yew (Taxus baccata), prickly juniper (Juniperus oxycedrus), and dawn redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides) have been reported to produce taxiphyllin, a tyrosine-derived cyanogenic glycoside (Bijl-van Dijk et al. 1974). Thus, it is likely that these species possess an enzyme similar to angiosperm CYP79s that can convert l-tyrosine into the taxiphyllin precursor p-hydroxyphenylacetaldoxime. In this study we screened the transcriptomes from 72 conifer species to search for CYP79 genes in this plant division. One of the identified candidates, CYP79A118 from T. baccata, was chosen for heterologous expression and in vitro biochemical characterization. In addition, the transcript abundance of CYP79A118 and accumulation of the cyanogenic glycoside taxiphyllin were measured in the different organs of T. baccata trees. Based on our data we conclude that CYP79A118 most likely contributes to the formation of taxiphyllin in T. baccata.

Results

Identification of CYP79 genes in the conifers

To identify putative CYP79 genes in the conifers (Pinophyta), transcriptomes from 72 conifer species (Table S1) generated from the OneKP initiative (https://sites.google.com/a/ualberta.ca/onekp/) were screened using a T BLASTN search with four CYP79 proteins (poplar CYP79D6, Arabidopsis CYP79F1, maize GRMZM2G011156T01 and GRMZM2G138248T01) from different plant species as queries. At the 38% sequence identity and 10−20 E-value cutoff, this initial search resulted in more than 2000 putative sequences. Further phylogenetic analysis with P450 sequences from different CYP families revealed seven full-length genes and ten gene fragments with similarity to angiosperm CYP79 genes (Fig. 1; Table S2). As currently treated, the conifers comprise six families: Cupressaceae, Taxaceae, Sciadopityaceae, Araucariaceae, Podocarpaceae, and Pinaceae (Gernandt et al. 2011). While seven out of 18 analysed transcriptomes from the Podocarpaceae, five out of eight analysed transcriptomes from the Taxaceae, and one out of 27 analysed transcriptomes from the Cupressaceae contained at least one CYP79 gene, no sequences with similarity to CYP79s were found in the transcriptomes from the Pinaceae, Araucariaceae, and Sciadopityaceae (Fig. 1). A dendrogram analysis of the conifer CYP79 genes and selected P450 genes from the CYP71 clan showed that the newly identified conifer genes formed a well-defined clade within the CYP79 family (Fig. 2). According to the standard P450 classification system that defines families and subfamilies based on a certain level of amino acid sequence identity (family, >40% identity; subfamily, >55% identity; (Nelson et al. 1996)), the conifer CYP79s were grouped into the CYP79A subfamily (See Table S2). Sequence motifs conserved in A-type P450 proteins such as the heme binding site (consensus sequence ProPheGlyxGlyArgArgxCysxGly) and the ProGluArgPhe motif (Durst and Nelson 1995) were also found in the conifer CYP79 proteins (Fig. 2).

Family distribution of CYP79 genes identified from the transcriptomes of 72 conifer species. The numbers in parentheses represent the number of transcriptomes containing putative CYP79 genes (in red) and total transcriptomes analysed in each family (in black). The phylogeny of the conifers presented was adapted from (Gernandt et al. 2011)

Dendrogram analysis (rooted tree) of conifer CYP79 proteins with characterized CYP79 proteins from angiosperms and selected members of other CYP families belonging to the CYP71 clan (which includes CYP79s). The tree was inferred using the neighbor-joining method and n = 1000 replicates for bootstrapping. Bootstrap values >50 are shown next to each node. The tree is drawn to scale, with branch lengths measured in the number of amino acid substitutions per site. AtCYP710A1 from Arabidopsis was chosen as outgroup

Biochemical characterization of CYP79A118 from Taxus baccata

For biochemical characterization of conifer CYP79s, we chose the gene WWSS98821 from Taxus baccata and expressed it heterologously in Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain WAT11, which carries the Arabidopsis cytochrome P450 reductase 1 (CPR1) (Pompon et al. 1996). WWSS98821 was designated as CYP79A118 according to the standard P450 nomenclature. Since CYP79A118 contains an extended N-terminus in comparison to angiosperm CYP79s (Fig. 3), the full-length protein and an N-terminal truncated version that starts with methionine at position 39 (CYP79A118-M39; Fig. 2) were both characterized. Microsomes harboring the recombinant proteins and CPR1 were incubated with the potential amino acid substrates l-tyrosine, l-tryptophan, l-phenylalanine, l-leucine, and l-isoleucine in the presence of the electron donor NADPH. Both, the full-length protein as well as the truncated version showed enzymatic activity with the aromatic amino acids and produced p-hydroxyphenylacetaldoxime, indole-3-acetaldoxime, and phenylacetaldoxime, but were not active with l-leucine and l-isoleucine (Fig. 4). Enzyme assays containing microsomes from a yeast culture expressing an empty vector revealed no aldoxime-producing activity and assays performed in the absence of NADPH showed only trace activity (See Fig. S1). Notably, the N-terminal truncated version CYP79A118-M39 had higher enzyme activity than the full-length protein (Fig. 4). However, quantification of the recombinant protein in the yeast microsomes by carbon monoxide difference spectra was inconclusive, and therefore it is still unclear whether the extended N-terminus of CYP79A118 decreased the overall catalytic efficiency of the enzyme or whether it affected the rate of heterologous expression and thus the amount of recombinant protein obtained. Since the substrate specificities of the full-length and truncated CYP79A118 were nearly identical (Fig. 4), we used the more active truncated version for kinetic analysis. The substrate affinity of CYP79A118-M39 for l-tyrosine (K m, 0.456 ± 0.061 mM) was in the range reported for other previously characterized angiosperm CYP79s (e.g. Andersen et al. 2000; Mikkelsen et al. 2000; Naur et al. 2003; Irmisch et al. 2013a, 2015). The high K m values for l-phenylalanine (21.69 ± 6.26 mM) and l-tryptophan (24.15 ± 11.64 mM) indicate that these amino acids are likely not substrates in planta. This assumption is strengthened by the fact that the relative product formation for l-tyrosine (4918 ± 132 ng/h/ml assay) was ~250 times higher in comparison to that for l-tryptophan (23.3 ± 1.4 ng/h/ml assay) and l-phenylalanine (20.0 ± 1.2 ng/h/ml assay). To verify the in vitro data, full-length CYP79A118 and N-terminal truncated CYP79A118-M39 were transiently expressed in Nicotiana benthamiana. Leaves of transgenic plants were harvested 5 days after infiltration and aldoxime accumulation was analyzed using LC-MS. While plants expressing eGFP as negative control showed no aldoxime formation, expression of CYP79A118 and CYP79A118-M39 both resulted in the accumulation of p-hydroxyphenylacetaldoxime (See Fig. S2). Indole-3-acetaldoxime and phenylacetaldoxime, however, could not be detected in the transgenic plants, corroborating the kinetic parameters obtained in vitro.

Amino acid alignment of conifer CYP79 enzymes with selected CYP79s from angiosperms. Amino acids identical in at least ten out of 12 sequences are marked by black boxes and amino acids with similar side chains are marked by gray boxes. Sequence motifs characteristic for CYP79 proteins are labeled. The methionine residue used as start codon for N-terminal truncated CYP79A118-M39 is marked in bold and underlined. CYP79B2, Arabidopsis thaliana; CYP79A1, S. bicolor; CYP79D6, Populus trichocarpa; CYP79C2, A. thaliana; CYP79F1, A. thaliana

Enzymatic activity of full-length (CYP79A118-M1) and N-terminal truncated (CYP79A118-M39) CYP79A118. The genes were heterologously expressed in S. cerevisiae and microsomes containing the recombinant proteins were incubated with the amino acid substrates l-tyrosine (Tyr), l-tryptophan (Trp), and l-phenylalanine (Phe). The aldoximes produced, p-hydroxyphenylacetaldoxime, indole-3-acetaldoxime, and phenylacetaldoxime, respectively, were detected using LC-MS/MS. CPS, counts per second (electron multiplier)

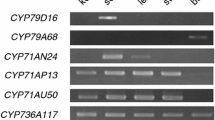

CYP79A118 transcript abundance in different organs of T. baccata

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was used to measure the transcript accumulation of CYP79A118 in leaves, twigs, roots, seeds, and arils of T. baccata trees. To identify a reference gene with stable expression in the different organs, we tested the transcript accumulation of actin (Sun et al. 2013), 18S RNA (Ramirez-Estrada et al. 2016), and GAPDH (Zheng et al. 2016). Based on its low variability among different organs, GAPDH was chosen as a reference gene (See Fig. S3). qRT-PCR analysis of CYP79A118 revealed transcript accumulation in roots, twigs, and leaves (Fig. 5a). In contrast, seeds and arils accumulated only trace levels of CYP79A118 transcripts.

Transcript abundance of CYP79A118 (a) and accumulation of taxiphyllin (b) in different organs of T. baccata. Gene expression was analyzed using qRT-PCR and taxiphyllin was measured using LC-MS/MS. Means and standard errors are shown (n = 7 biological replicates). A one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey’s honest significance test was used to test for statistical significance. Different letters indicate significant differences between plant organs. CYP79A118 gene expression: F = 8.039, P < 0.01; taxiphyllin accumulation: F = 30.16, P < 0.001)

Accumulation of taxiphyllin in different organs of T. baccata

Taxiphyllin has been described as the sole cyanogenic glycoside in leaves of different conifers, including T. baccata (Hegenauer 1959; Bijl-van Dijk et al. 1974). We used liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) to quantify and compare the accumulation of taxiphyllin in the different plant organs of T. baccata. Highest amounts of taxiphyllin were found in leaves and twigs with 879 ± 131 ng/g fresh weight and 733 ± 84 ng/g fresh weight, respectively (Fig. 5b). Roots showed moderate accumulation (285 ± 46 ng/g fresh weight) while seeds and arils accumulated only trace amounts of taxiphyllin (Fig. 5b). Other cyanogenic glycosides such as prunasin, lotaustralin, linamarin, and amygdalin, which are commonly found in angiosperms, as well as the CYP79A118 product p-hydroxyphenylacetaldoxime could not be detected in the analyzed tissues.

Discussion

CYP79A118 is most likely involved in taxiphyllin formation

CYP79 enzymes play multiple roles in the biosynthesis of plant defense compounds and have been intensively investigated in angiosperms. However, whether these enzymes also occur in other plants such as gymnosperms and ferns has remained unclear. In this study, we report the identification of CYP79A genes in the transcriptomes of several conifer species. One of the genes, CYP79A118 from T. baccata, was heterologously expressed in yeast and the recombinant enzyme produced p-hydroxyphenylacetaldoxime from l-tyrosine as substrate (Fig. 4). Although phenylalanine and tryptophan were also converted into aldoximes by recombinant CYP79A118 in vitro, the high K m and low V max values for both of these amino acids in comparison to those for tyrosine indicate that they are not employed as substrates in vivo. Indeed, transgenic N. benthamiana plants transiently expressing CYP79A118 accumulated exclusively p-hydroxyphenylacetaldoxime and no other aldoximes (See Fig. S2). Several conifer species including T. baccata have been described to accumulate only a single cyanogenic glycoside, taxiphyllin, a compound derived from p-hydroxyphenylacetaldoxime (Towers et al. 1964; Bijl-van Dijk et al. 1974; Nahrstedt 1979). Considering its substrate specificity, it is conceivable that CYP79A118 catalyzes the first step in the formation of taxiphyllin in T. baccata. However, the genome of T. baccata is still not sequenced and thus we cannot exclude the presence of additional CYP79s that might provide p-hydroxyphenylacetaldoxime as precursor for taxiphyllin in this species instead or in addition to CYP79A118.

Taxiphyllin was found to accumulate in leaves, twigs, and roots, but not in seeds and arils (Fig. 5b). These findings confirm an older study, which reported that seeds and arils of T. baccata have no cyanide potential (Barnea et al. 1993). The accumulation of the cyanogenic glycoside dhurrin in sorghum has been shown to be regulated at the transcriptional level of CYP79A1 and CYP71E1, the first two enzymes of the dhurrin pathway (Busk and Moller 2002). Since CYP79A118 is exclusively expressed in plant organs rich in taxiphyllin (Fig. 5), we hypothesize that it also controls cyanogenic glycoside accumulation in T. baccata. A possible co-regulation of taxiphyllin formation by CYP79A118 and the subsequent enzymatic step, the p-hydroxymandelonitrile-forming enzyme, as for dhurrin formation in sorghum CYP79A1 and CYP71E1 (Busk and Moller 2002), might allow the identification of the second step of taxiphyllin formation in T. baccata, probably catalyzed by a CYP71/736 homolog, via gene co-expression analysis.

The enzymes of the cyanogenic glycoside biosynthetic pathway in sorghum, CYP79A1, CYP71E1, UGT85B1, and a P450 reductase, are thought to be organized in membrane-associated protein complexes called metabolons, which promote channelling of the toxic and unstable intermediates and thus prevent autointoxication and loss of intermediates to side reactions (Nielsen et al. 2008; Moller 2010b; Jensen et al. 2011; Laursen et al. 2016). We could not detect aldoximes in our analyses of T. baccata trees and it is thus conceivable that the biosynthetic machinery for cyanogenic glycoside production in Taxus is also organized in protein complexes that do not allow the accumulation of free aldoximes.

CYP79s represent an ancient P450 family in plants

CYP79s belong to a group of plant P450s that has been designated as CYP71 clan (Fig. 2). This multi-family clan, which comprises more than 37 CYP families, is believed to have evolved early in the evolution of the land plants (Nelson 2006; Nelson and Werck-Reichhart 2011). Until now, CYP79s were only known from angiosperms and were speculated to have arisen with the Magnoliids, a basal clade of the angiosperms (Nelson and Werck-Reichhart 2011; Hamberger and Bak 2013). The identification of CYP79A genes in the conifers now demonstrates that CYP79 genes must have been present already in a common ancestor of the gymnosperms and angiosperms, which presumably existed in the middle of the Carboniferous period about 330 million years ago (Smith et al. 2010). Since some fern species are able to produce cyanogenic glycosides (Kofod and Eyjolfsson 1966, 1969), it is conceivable that they also possess CYP79 genes for the production of the respective aldoxime precursors. Such a scenario would place the origin of CYP79s back in the early evolution of vascular plants about 430–400 million years ago (Smith et al. 2010).

Many angiosperms possess small CYP79 gene families with an average number of four to five members (Irmisch et al. 2013a) and the encoded proteins are known to play diverse roles in plant defence. CYP79s, for instance, are not only the entry enzymes for cyanogenic glycoside formation, but can also produce aldoximes as precursors for other defence compounds such as glucosinolates and various phytoalexins (Halkier and Gershenzon 2006; Glawischnig 2007). Moreover, CYP79s are involved in herbivore-induced volatile formation (Irmisch et al. 2013a, 2014; Irmisch 2013b; McCormick et al. 2014; Luck et al. 2016) and they have been discussed to play a role in auxin homeostasis (Bak and Feyereisen 2001; Sugawara et al. 2009; Irmisch et al. 2015). In contrast, most of the conifer transcriptomes analysed in this study contained only a single CYP79 gene, but the transcriptomes of the Podocarpaceae species Phyllocladus hypophyllus and the Taxaceae species Amentotaxus argotaenia and Torreya taxifolia contained two or three different CYP79 gene fragments (See Table S2). Multiple CYP79 gene copies in gymnosperm genomes might fulfil diverse biological roles comparable to those in angiosperms. However, the fact that ferns, conifers, and angiosperms all produce cyanogenic glycosides suggests an original function of CYP79s in the formation of these compounds.

Methods

Plant material

For the isolation of CYP79A118, T. baccata leaves were collected in September 2014 from a single tree growing near Ruhla, Thuringia, Germany (50°53′28.1"N 10°22′13.6"E). Plant material for cyanogenic glycoside analysis and qRT-PCR was collected in August 2016 from seven individual trees growing in Großeutersdorf, Thuringia, Germany (50°47′22.6"N 11°33′56.3"E).

LC-MS/MS analysis of cyanogenic glycosides and aldoximes

Taxiphyllin was analyzed according to a previously described method for cyanogenic glycoside analysis (Irmisch et al. 2015). In brief, plant material was ground to powder in an ice-cold mortar. For extraction, 100 mg of frozen powder was transferred to a pre-cooled 2 ml microcentrifuge tube and 600 µl of ice-cold extraction solvent (80% aqueous methanol, gradient grade for liquid chromatography) were added. The tubes were immediately mixed until the powder was completely dispersed, and three chrome steel beads (4 mm diameter) were added to each tube. Plant tissues were subsequently extracted using a paint shaker (S0-10 M, Fluid Management, Wheeling, IL, USA) at 10 Hz for 4 min and cell debris was sedimented at 13,000 g for 30 min. The supernatant was stored at −20 °C before analysis.

Plant extracts were analyzed using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) performed on an Agilent 1200 HPLC system coupled to an API 5000 tandem mass spectrometer (Applied Biosystems, Darmstadt, Germany). Separation was achieved on a Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C18 column (50 × 4.6 mm, 1.8 µm, Agilent Technologies) with aqueous formic acid (0.2% v/v) and acetonitrile employed as mobile phases A and B, respectively. For the analysis of cyanogenic glycosides, the following elution profile was used: 0–0.5 min, 5% B in A; 0.5–6.0 min, 5–50% B; 6.0–7.5 min 100% B, and 7.5–10.5 min 5% B. The flow rate was set to 1.1 ml/min. The injection volume was 2 µl. The tandem mass spectrometer was operated in negative ionization mode (ionspray voltage, −4500 eV; turbo gas temp, 700 °C; nebulizing gas, 60 psi; curtain gas, 30 psi; heating gas, 50 psi; collision gas, 6 psi). The following mass analyzer settings were applied: collision energy (CE), −10 V; and declustering potential (DP), −15 V. MRM was used to monitor parent ion → product ion reactions for each analyte as follows: m/z 310.0 → 179.0 for taxiphyllin/dhurrin, m/z 294.0 → 89.0 (CE, −22; DP, −15) for prunasin, m/z 260.0 → 179.0 for lotaustralin, m/z 246.0 → 179.0 for linamarin, and m/z 456.0 → 179.0 for amygdalin. For quantification, the taxiphyllin enantiomer dhurrin was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich and used as external standard (See Fig. S4).

Aldoximes were measured from the same MeOH extracts using the same LC-MS/MS system as described above. Formic acid (0.2%) in water and acetonitrile were employed as mobile phases A and B, respectively, on a Zorbax Eclipse XDB-C18 column (50 × 4.6 mm, 1.8 µm). The elution profile was: 0–4 min, 10–70% B; 4–4.1 min, 70–100% B; 4.1–5 min 100% B, and 5.1–7 min 10% B at a flow rate of 1.1 ml/min. The tandem mass spectrometer was operated in positive ionization mode (ionspray voltage, 5500 eV; turbo gas temp, 700 °C; nebulizing gas, 60 psi; curtain gas, 30 psi; heating gas, 50 psi; collision gas, 6 psi). MRM was used to monitor precursor ion → product ion reactions for each analyte as follows: m/z 136.0 → 119.0 (collision energy (CE), 17 V; declustering potential (DP), 56 V) for phenylacetaldoxime; m/z 175.0 → 158.0 (CE, 17 V; DP, 56 V) for indole-3-acetaldoxime, m/z 102.0 → 69.0 (CE, 13 V; DP, 31 V) for 2-methylbutyraldoxime; m/z 102.0 → 46.0 (CE, 15 V; DP, 31 V) for 3-methylbutyraldoxime, and m/z 152.0 → 107.0 (CE, 27 V; DP, 100 V) for p-hydroxyphenylacetaldoxime. The concentration of aldoximes was determined using external standard curves made with authentic standards synthesized as described in the literature (Irmisch et al. 2013a).

RNA extraction and reverse transcription

Taxus baccata plant material (leaves, roots, bark, arills, seeds) was flash-frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored at −80 °C until further processing. Total RNA was isolated from ground plant tissue using an InviTrap Spin Plant RNA kit (Stratec, Berlin, Germany) according to manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentration and purity were assessed using a spectrophotometer (NanoDrop 2000c, Thermo Scientific, Wilmington, DE, USA). RNA was treated with TurboDNase (ThermoFisher Scientific, https://www.thermofisher.com) prior to cDNA synthesis. Single-stranded cDNA was prepared from 1 µg of DNase-treated RNA using SuperScript™ III reverse transcriptase and oligo (dT12–18) primers (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Identification of CYP79 genes in conifers

Transcriptomes of 72 different conifer species (See Table S1) were downloaded from OneKP (https://sites.google.com/a/ualberta.ca/onekp/). The annotated protein sequences (Jia and Chen 2016) were searched for homologs of angiosperm CYP79s using BLASTP. At a combined threshold of E-value (10−20) and identity (38%), 2134 putative sequences were identified. In view of high sequence similarity shared by CYP79s and other P450 families, such as CYP703 family, a phylogenetic analysis with P450 sequences from different families was used to remove non-CYP79 sequences. The full-length genes identified were designated as CYP79A117 (M. glyptostroboides), CYP79A118 (T. baccata), CYP79A119 (Dacrycarpus compactus), CYP79A120 (Dacrydium balansae), CYP79A121 (Falcatifolium taxoides), CYP79A122 (A. argotaenia), and CYP79A123 (T. taxifolia) according to the general P450 nomenclature (D.R. Nelson, P450 Nomenclature Committee). Some of these genes may be orthologous, but transcriptomes do not provide synteny data to verify this. The complete open reading frame of CYP79A118 was amplified from cDNA obtained from T. baccata leaves. The PCR product was cloned into the sequencing vector pCR®-Blunt II-TOPO® (Invitrogen) and both strands were fully sequenced using the Sanger method. Primer sequence information is given in Table S3.

Heterologous expression of CYP79A118 in yeast

For heterologous expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the complete open reading frame of CYP79A118 and the 5′ truncated version CYP79A118-M39 were cloned into the pESC-Leu2d vector (Ro et al. 2008) as NotI/SacI fragments. The resulting constructs were transferred into the S. cerevisiae strain WAT11 (Pompon et al. 1996) and single yeast colonies were picked to inoculate starting cultures containing 30 ml SC minimal medium lacking leucine (6.7 g/l yeast nitrogen base without amino acids, but with ammonium sulfate). Other components: 100 mg/l of l-adenine, l-arginine, l-cysteine, l-lysine, l-threonine, l-tryptophan and uracil; 50 mg/l of the amino acids l-aspartic acid, l-histidine, l-isoleucine, l-methionine, l-phenylalanine, l-proline, l-serine, l-tyrosine, l-valine; 20 g/l d-glucose. The cultures were grown overnight at 28 °C and 180 rpm. One OD of the starting cultures (approx. 2 × 107 cells/ml) was used to inoculate 100 ml YPGA full medium cultures (10 g/l yeast extract, 20 g/l bactopeptone, 74 mg/l adenine hemisulfate, 20 g/l d-glucose) which were grown for 32–35 h (until OD about five), induced by the addition of galactose and cultured for another 15–18 h. The cultures were centrifuged (7500 g, 10 min, 4 °C), the supernatant was decanted, and the cell pellets were resuspended in 30 ml TEK buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 100 mM KCl) and centrifuged again. Then, the pellets were carefully resuspended in 2 ml of TES buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl pH 7.5, 1 mM EDTA, 600 mM sorbitol, 10 g/l bovine serum fraction V protein and 1.5 mM β-mercaptoethanol) and transferred to a 50 ml conical tube. Glass beads (0.45–0.50 mm diameter, Sigma–Aldrich Chemicals, Steinheim, Germany) were added so that they filled the full volume of the cell suspension. Yeast cell walls were disrupted by five cycles of 1 min shaking by hand and subsequent cooling down on ice for 1 min. The crude extracts were recovered by washing the glass beads four times with 5 ml TES. The combined washes were centrifuged (7500 g, 10 min, 4 °C), and the supernatant was transferred to another tube and centrifuged again (100,000 g, 60 min, 4 °C). The resulting microsomal protein fractions were homogenized in 2 ml TEG buffer (50 mM Tris–HCl, 1 mM EDTA, 30% w/v glycerol) using a glass homogenizer (Potter–Elvehjem, Fisher Scientific, Schwerte, Germany). Aliquots were stored at −20 °C.

Analysis of recombinant CYP79A118

To determine the substrate specificity of full-length and N-terminal truncated CYP79A118, yeast microsomes harboring recombinant protein were incubated for 60 min at 25 °C and 300 rpm individually with the potential substrates l-Phe, l-Val, l-Leu, l-Ile, l-Tyr, and l-Trp in glass vials containing 300 µl of the reaction mixture (75 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0), 1 mM substrate (concentration was variable for K m determination), 1 mM NADPH, and 10 µl of the prepared microsomes). Reaction products where analyzed using LC-MS/MS as described below.

For the determination of the K m values, assays were carried out as triplicates and stopped by placing on ice after 300 µl MeOH were added. Enzyme concentrations and incubation times were chosen so that the reaction velocity was linear during the incubation time period.

Transient expression of CYP79A118 and CYP79A118-M39 in N. benthamiana

For gene expression in N. benthamiana, the complete ORF as well as the N-terminal truncated ORF (M39) of CYP79A118 were cloned into the pCAMBiA2300U vector. Resulting vectors carrying either one of the CYP79A118 constructs, eGFP, or the construct pBIN::p19 were separately transferred into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain LBA4404. Five milliliter of an overnight culture (220 rpm, 28 °C) were used to inoculate 50 ml LB medium (50 µg/ml kanamycin, 25 µg/ml rifampicin and 25 µg/ml gentamicin) for overnight growth. The following day, the cultures were centrifuged (4000 g, 5 min) and the cells were resuspended in infiltration buffer (10 mM MES, 10 mM MgCl2, 100 µM acetosyringone, pH 5.6) to reach a final OD of 0.5. After shaking for at least 1 h at room temperature, the cultures carrying CYP79A118, CYP79A118-M39, or eGFP were mixed with an equal volume of cultures carrying pBIN::p19.

For transformation, 3–4 week-old N. benthamiana plants were dipped upside down in an A. tumefaciens solution and vacuum was applied to infiltrate the leaves. Infiltrated plants were shaded with cotton tissue to protect them from direct irradiation. Five days after transformation, CYP79A118 products were extracted with methanol from grinded leaves and measured using LC-MS/MS as described above.

qRT-PCR analysis

cDNA was prepared as described above and diluted 1:10 with water. qPCR primers for CYP79A118 were designed having a Tm ≥ 60 °C, a GC content between 50–58%, and a primer length of 21 nucleotides (Table S3). The amplicon size was 108 bp. The specificity and efficiency of the primers were confirmed by agarose gel electrophoresis, melting curve analysis, standard curve analysis, and by sequence verification of cloned PCR amplicons. Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) was used as a reference gene (Zheng et al. 2016). Samples were run in triplicate using Brilliant III Ultra-Fast SYBR® Green QPCR Master Mix (Stratagene, Carlsbad, CA, USA). The following PCR conditions were applied for all reactions: Initial incubation at 95 °C for 3 min followed by 40 cycles of amplification (95 °C for 5 s, 60 °C for 10 s). Plate reads were taken at the end of the extension step of each cycle. Data for the melting curves were recorded at the end of cycling from 60 to 95 °C.

All samples were run on the same PCR machine (Bio-Rad CFX Manager 3.1, Bio-Rad Laboratory, Hercules, CA, USA) in an optical 96-well plate. For each tissue, seven biological replicates were analyzed in triplicate.

Sequence analysis and phylogenetic tree construction

An alignment of conifer CYP79 genes and characterized CYP genes from angiosperms was constructed using the MUSCLE (codon) algorithm (gap open, −2.9; gap extend, 0; hydrophobicity multiplier, 1.2; clustering method, UPGMB) implemented in MEGA6 (Tamura et al. 2011). Tree reconstruction was done with MEGA6 using a maximum likelihood algorithm (model/method, General Time Reversible model; substitutions type, nucleotide; rates among sites, gamma distributed (G); gamma parameters, 5; gaps/missing data treatment, partial deletion; site coverage cutoff, 90%). A bootstrap resampling analysis with 1000 replicates was performed to evaluate the tree topology.

Statistical analysis

Differences in taxiphyllin content and relative expression of CYP79A118 in the tested organs of T. baccata trees were analyzed with one-way ANOVAs. Pairwise comparisons were performed with Tukey’s honest significance test (α = 0.05) using the agricolae package in R (R Core Team 2014; de Mendiburu et al. 2014). Data are presented as means ± SE.

Change history

30 October 2017

Due to an unfortunate turn of events, the funding note for Open Access publication was not properly provided in the original publication. Hence, the original article has been corrected. The opening line of the Acknowledgement section should read:

Abbreviations

- CYP:

-

Cytochrome P450 monooxygenase

- qRT-PCR:

-

Quantitative real-time PCR

- LC-MS/MS:

-

Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry

References

Andersen MD, Busk PK, Svendsen I, Moller BL (2000) Cytochromes P-450 from cassava (Manihot esculenta Crantz) catalyzing the first steps in the biosynthesis of the cyanogenic glucosides linamarin and lotaustralin—cloning, functional expression in Pichia pastoris, and substrate specificity of the isolated recombinant enzymes. J Biol Chem 275:1966–1975

Bak S, Feyereisen R (2001) The involvement of two P450 enzymes, CYP83B1 and CYP83A1, in auxin homeostasis and glucosinolate biosynthesis. Plant Physiol 127:108–118

Bak S, Kahn RA, Nielsen HL, Moller BL, Halkier BA (1998) Cloning of three A-type cytochromes p450, CYP71E1, CYP98, and CYP99 from Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench by a PCR approach and identification by expression in Escherichia coli of CYP71E1 as a multifunctional cytochrome p450 in the biosynthesis of the cyanogenic glucoside dhurrin. Plant Mol Biol 36:393–405

Barnea A, Harborne JB, Pannell C (1993) What parts of fleshy fruits contain secondary compounds toxic to birds and why? Biochem Syst Ecol 21:421–429

Bijl-van Dijk B, van der Plas-De Wijs A, Ruijgrok HWL (1974) Cyanogenese bei den Gymnospermen. Phytochemistry 13:159–160

Busk PK, Moller BL (2002) Dhurrin synthesis in sorghum is regulated at the transcriptional level and induced by nitrogen fertilization in older plants. Plant Physiol 129:1222–1231

de Mendiburu F (2014) Agricolae: statistical procedures for agricultural research. R Package Version 1.2-0 1(1):ed2014

Durst F, Nelson DR (1995) Diversity and evolution of plant P450 and P450-reductases. Drug Metab Drug Interact 12:189–206

Frey M, Schullehner K, Dick R, Fiesselmann A, Gierl A (2009) Benzoxazinoid biosynthesis, a model for evolution of secondary metabolic pathways in plants. Phytochemistry 70:1645–1651

Gernandt DS, Willyard A, Syring JV, Liston A (2011) The conifers (Pinophyta). In: Plomion C, Bousquet J, Kole C (eds) Genetics, genomics and breeding in conifers, Science Publishers, New Hampshire, pp 1–39

Gershenzon J, Croteau R (1991) Terpenoids. In: Rosenthal GA, Berenbaum MR (eds) Herbivores: their interaction with secondary plant metabolites, vol. 1, Academic Press, San Diego, pp 165–209

Glawischnig E (2007) Camalexin. Phytochemistry 68:401–406

Gleadow RM, Moller BL (2014) Cyanogenic glycosides: synthesis, physiology, and phenotypic plasticity. Annu Rev Plant Biol 65:155–185

Gleadow RM, Woodrow IE (2002) Constraints on effectiveness of cyanogenic glycosides in herbivore defense. J Chem Ecol 28:1301–1313

Halkier BA, Gershenzon J (2006) Biology and biochemistry of glucosinolates. Annu Rev Plant Biol 57:303–333

Halkier BA, Olsen CE, Moller BL (1989) The biosynthesis of cyanogenic glucosides in higher-plants—the (E)-isomers and (Z)-isomers of para-hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde oxime as intermediates in the biosynthesis of dhurrin in Sorghum bicolor (L) Moench. J Biol Chem 264:19487–19494

Halkier BA, Nielsen HL, Koch B, Moller BL (1995) Purification and characterization of recombinant cytochrome p450(tyr) expressed at high-levels in Escherichia coli. Arch Biochem Biophys 322:369–377

Hamberger B, Bak S (2013) Plant P450s as versatile drivers for evolution of species-specific chemical diversity. Philos Trans R Soc B-Biol Sci 368:20120426

Harper NL, Cooperdriver GA, Swain T (1976) Survey for cyanogenesis in ferns and gymnosperms. Phytochemistry 15:1764–1767

Hegenauer R (1959) Die verbreitung der blausäure bei den cormophyten: 2. Mitteilung. Die cyanogenese im genus Taxus. Pharmaceutisch Weekblad 94:8

Irmisch S (2013b) Identification and characterization of CYP79D6v4, a cytochrome P450 enzyme producing aldoximes in black poplar (Populus nigra). Plant Signal Behav 8:e27640

Irmisch S, McCormick AC, Boeckler GA, Schmidt A, Reichelt M, Schneider B, Block K, Schnitzler JP, Gershenzon J, Unsicker SB, Kollner TG (2013a) Two herbivore-induced cytochrome P450 enzymes CYP79D6 and CYP79D7 catalyze the formation of volatile aldoximes involved in poplar defense. Plant Cell 25:4737–4754

Irmisch S, McCormick AC, Gunther J, Schmidt A, Boeckler GA, Gershenzon J, Unsicker SB, Kollner TG (2014) Herbivore-induced poplar cytochrome P450 enzymes of the CYP71 family convert aldoximes to nitriles which repel a generalist caterpillar. Plant J 80:1095–1107

Irmisch S, Zeltner P, Handrick V, Gershenzon J, Kollner TG (2015) The maize cytochrome P450 CYP79A61 produces phenylacetaldoxime and indole-3-acetaldoxime in heterologous systems and might contribute to plant defense and auxin formation. BMC Plant Biol 15:128

Jensen K, Osmani SA, Hamann T, Naur P, Moller BL (2011) Homology modeling of the three membrane proteins of the dhurrin metabolon: catalytic sites, membrane surface association and protein-protein interactions. Phytochemistry 72:2113–2123

Jia Q, Chen F (2016) Catalytic functions of the isoprenyl diphosphate synthase superfamily in plants: a growing repertoire. Mol Plant 9:189–191

Jones PR, Moller BL, Hoj PB (1999) The UDP-glucose : p-hydroxymandelonitrile-O-glucosyltransferase that catalyzes the last step in synthesis of the cyanogenic glucoside dhurrin in Sorghum bicolor—Isolation, cloning, heterologous expression, and substrate specificity. J Biol Chem 274:35483–35491

Jorgensen K, Morant AV, Morant M, Jensen NB, Olsen CE, Kannangara R, Motawia MS, Moller BL, Bak S (2011) Biosynthesis of the cyanogenic glucosides linamarin and lotaustralin in cassava: isolation, biochemical characterization, and expression pattern of CYP71E7, the oxime-metabolizing cytochrome P450 enzyme. Plant Physiol 155:282–292

Kannangara R, Motawia MS, Hansen NKK, Paquette SM, Olsen CE, Moller BL, Jorgensen K (2011) Characterization and expression profile of two UDP-glucosyltransferases, UGT85K4 and UGT85K5, catalyzing the last step in cyanogenic glucoside biosynthesis in cassava. Plant J 68:287–301

Kofod H, Eyjolfss R (1966) Isolation of cyanogenic glycoside prunasin from Pteridium aquilinum (L) Kuhn. Tetrahedron Lett 7(12):1289–1291

Kofod H, Eyjolfsson R (1969) Cyanogenesis in species of fern genera Cystopteris and Davallia. Phytochemistry 8:1509–1511

Laursen T, Borch J, Knudsen C, Bavishi K, Torta F, Martens HJ, Silvestro D, Hatzakis NS, Wenk MR, Dafforn TR, Olsen CE, Motawia MS, Hamberger B, Moller BL, Bassard JE (2016) Characterization of a dynamic metabolon producing the defense compound dhurrin in sorghum. Science 354:890–893

Luck K, Jirschitzka J, Irmisch S, Huber M, Gershenzon J, Kollner TG (2016) CYP79D enzymes contribute to jasmonic acid-induced formation of aldoximes and other nitrogenous volatiles in two erythroxylum species. BMC Plant Biol 16:250

McCormick AC, Irmisch S, Reinecke A, Boeckler GA, Veit D, Reichelt M, Hansson BS, Gershenzon J, Kollner TG, Unsicker SB (2014) Herbivore-induced volatile emission in black poplar: regulation and role in attracting herbivore enemies. Plant Cell Environ 37:1909–1923

McFarlane IJ, Lees EM, Conn EE (1975) In vitro biosynthesis of dhurrin, cyanogenic glycoside of Sorghum bicolor. J Biol Chem 250:4708–4713

Mikkelsen MD, Hansen CH, Wittstock U, Halkier BA (2000) Cytochrome P450 CYP79B2 from Arabidopsis catalyzes the conversion of tryptophan to indole-3-acetaldoxime, a precursor of indole glucosinolates and indole-3-acetic acid. J Biol Chem 275:33712–33717

Moller BL (2010a) Functional diversifications of cyanogenic glucosides. Curr Opin Plant Biol 13:338–347

Moller BL (2010b) Dynamic metabolons. Science 330:1328–1329

Moller BL, Conn EE (1979) Biosynthesis of cyanogenic glucosides in higher plants—n-hydroxytyrosine as an intermediate in the biosynthesis of dhurrin by Sorghum bicolor (L) Moench. J Biol Chem 254:8575–8583

Nahrstedt A (1979) Qualitative and quantitative determination of the cyanoglucosides trigloquinine, taxiphylline and dhurrine by high-pressure liquid-chromatography. J Chromatogr 177:157–161

Naur P, Hansen CH, Bak S, Hansen BG, Jensen NB, Nielsen HL, Halkier BA (2003) CYP79B1 from Sinapis alba converts tryptophan to indole-3-acetaldoxime. Arch Biochem Biophys 409:235–241

Nelson DR (2006) Plant cytochrome P450s from moss to poplar. Phytochem Rev 5:193–204

Nelson DR, Werck-Reichhart D (2011) A P450-centric view of plant evolution. Plant J 66:194–211

Nelson DR, Koymans L, Kamataki T, Stegeman JJ, Feyereisen R, Waxman DJ, Waterman MR, Gotoh O, Coon MJ, Estabrook RW, Gunsalus IC, Nebert DW (1996) P450 super family: update on new sequences, gene mapping, accession numbers and nomenclature. Pharmacogenetics 6:1–41

Nielsen KA, Tattersall DB, Jones PR, Moller BL (2008) Metabolon formation in dhurrin biosynthesis. Phytochemistry 69:88–98

Osbourn AE (1996) Preformed antimicrobial compounds and plant defense against fungal attack. Plant Cell 8:1821–1831

Pompon D, Louerat B, Bronine A, Urban P (1996) Yeast expression of animal and plant P450s in optimized redox environments. Cytochrome P450(272):51–64

R Core Team (2014) A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna

Ramirez-Estrada K, Altabella T, Onrubia M, Moyano E, Notredame C, Osuna L, Bossche RV, Goossens A, Cusido RM, Palazon J (2016) Transcript profiling of jasmonate-elicited Taxus cells reveals a beta-phenylalanine-CoA ligase. Plant Biotechnol J 14:85–96

Rausher MD (2006) The evolution of flavonoids and their genes. In: Grotewold E (ed.) The science of flavonoids, Springer, New York, pp 175–211

Ro DK, Ouellet M, Paradise EM, Burd H, Eng D, Paddon CJ, Newman JD, Keasling JD (2008) Induction of multiple pleiotropic drug resistance genes in yeast engineered to produce an increased level of anti-malarial drug precursor, artemisinic acid. BMC Biotechnol 8:83

Selmar D, Lieberei R, Biehl B (1988) Mobilization and utilization of cyanogenic glycosides—the linustatin pathway. Plant Physiol 86:711–716

Sibbesen O, Koch B, Halkier BA, Moller BL (1995) Cytochrome p450(tyr) is a multifunctional heme-thiolate enzyme catalyzing the conversion of l-tyrosine to p-hydroxyphenylacetaldehyde oxime in the biosynthesis of the cyanogenic glucoside dhurrin in Sorghum bicolor (L) Moench. J Biol Chem 270:3506–3511

Smith SA, Beaulieu JM, Donoghue MJ (2010) An uncorrelated relaxed-clock analysis suggests an earlier origin for flowering plants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 107:5897–5902

Sugawara S, Hishiyama S, Jikumaru Y, Hanada A, Nishimura T, Koshiba T, Zhao Y, Kamiya Y, Kasahara H (2009) Biochemical analyses of indole-3-acetaldoximedependent auxin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106:5430–5435

Sun GL, Yang YF, Xie FL, Wen JF, Wu JQ, Wilson IW, Tang Q, Liu HW, Qiu DY (2013) Deep sequencing reveals transcriptome re-programming of Taxus x media cells to the elicitation with methyl jasmonate. Plos ONE 8:e62865

Takos AM, Knudsen C, Lai D, Kannangara R, Mikkelsen L, Motawia MS, Olsen CE, Sato S, Tabata S, Jørgensen K, Møller BL, Rook F (2011) Genomic clustering of cyanogenic glucoside biosynthetic genes aids their identification in Lotus japonicus and suggests the repeated evolution of this chemical defence pathway. Plant J 68:273–286

Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S (2011) MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol Biol Evol 28:2731–2739

Towers GHN, Neish AC, McInnes AG (1964) Absolute configurations of phenolic cyanogenetic glucosides taxiphyllin and dhurrin. Tetrahedron 20:71–77

Zagrobelny M, Bak S, Rasmussen AV, Jorgensen B, Naumann CM, Moller BL (2004) Cyanogenic glucosides and plant–insect interactions. Phytochemistry 65:293–306

Zagrobelny M, Bak S, Moller BL (2008) Cyanogenesis in plants and arthropods. Phytochemistry 69:1457–1468

Zheng W, Komatsu S, Zhu W, Zhang L, Li XM, Cui L, Tian JK (2016) Response and defense mechanisms of Taxus chinensis leaves under UV—a radiation are revealed using comparative proteomics and metabolomics analyses. Plant Cell Physiol 57:1839–1853

Acknowledgements

Open Access funding provided by Max Planck Society. This research was funded by the Max-Planck Society. The 1000 Plants (1KP) initiative led by GKSW was funded by the Alberta Ministry of Advanced Education, Alberta Innovates Technology Futures (AITF), Innovates Centres of Research Excellence (iCORE), Musea Ventures, and China National GeneBank (CNGB). The BGI-Shenzhen group was funded by the Shenzhen Supporting Projects Program under Grant CXZZ20140421112021913.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

TGK, KL, FC, GKSW, DRN, and JG designed research. KL, TGK, QJ, and VH carried out the experimental work. TGK, KL, MH, and DRN analyzed data. TGK wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interests.

Additional information

Accession numbers

Sequence data for genes in this article can be found in the GenBank under the following identifiers CYP79A117 (KX931078), CYP79A118 (KX931079), CYP79A119 (KX931080), CYP79A120 (KX931081), CYP79A121 (KX931082), CYP79A122 (KX931083), CYP79A123 (KX931084).

A correction to this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1007/s11103-017-0674-9.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Luck, K., Jia, Q., Huber, M. et al. CYP79 P450 monooxygenases in gymnosperms: CYP79A118 is associated with the formation of taxiphyllin in Taxus baccata . Plant Mol Biol 95, 169–180 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11103-017-0646-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11103-017-0646-0