Abstract

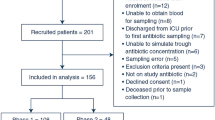

Background Therapeutic drug monitoring is frequently used to optimize the gentamicin dose. Objective The study investigated whether a 240 mg once daily standard dose achieves the recommended target serum gentamicin concentrations. Setting The prospective, observational study took place in the 2 major public hospitals in Namibia. Method Twenty-nine female patients receiving a standard dose (240 mg gentamicin once daily) participated in the study. Two blood samples were withdrawn to estimate gentamicin pharmacokinetic parameters. Serum creatinine was used to calculate creatinine clearance with the Cockcroft–Gault formula (CLcr), and estimate glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) by the Modified Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) and Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration (CKD-EPI) equations. Main outcome measure The outcome measure was the proportion of patients receiving 240 mg gentamicin once daily having Cmax values above 15 mg/L. Results Total body weight (TBW) and body mass index were highly variable: 43–115 kg, and 17.3–41.3 kg/m2, respectively. The gentamicin dose normalized for TBW (adjusted body weight for obese patients) was relatively low, i.e. 4.2 ± 0.8 mg/kg (mean SD). Gentamicin Cmax was 14.4 ± 4.7 mg/L; only 9 patients (31%) had a Cmax > 15 g/mL. eGFR (MDRD-4) correlated well with CLcr, but eGFR (EPI-CKD) formula showed systematic deviations from CLcr. Conclusions (1) a standard 240 mg dose results in gentamicin Cmax values below 15 mg/L in the majority of the patients, (2) eGFR formulas to estimate kidney function will have to be evaluated for their usefulness in the Namibian patient population.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

MacDougall C, Chambers HF. Aminoglycosides. In: Brunton L, Chabner B, Knollman B, editors. Goodman & Gilman’s the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. 12th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2012. p. 1505–20.

Lietman PS, Smith CR. Aminoglycoside nephrotoxicity in humans. J Infect Dis. 1983;5(Suppl. 2):S284–92.

Guthrie OW. Aminoglycoside-induced ototoxicity. Toxicology. 2008;249:91–6.

Noone P, Parsons TMC, Pattison JR, Slack RC, Garfield-Davies D, Hughes K. Experience in monitoring gentamicin therapy during treatment of serious gram-negative sepsis. Br Med J. 1974;5906:477–81.

Barza M, Lauermann M. Why monitor serum levels of gentamicin? Clin Pharmacokinet. 1978;3:202–15.

Roberts JA, Norris R, Paterson DL, Martin JH. Therapeutic drug monitoring of antimicrobials. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;73:27–36.

Begg EJ, Barclay ML, Duffull SB. A suggested approach to once-daily aminoglycoside dosing. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1995;39:605–9.

Hodiamont CJ, Juffermans NP, Bouman CSC, de Jong MD, Mathôt RA, van Hest RM. Determinants of gentamicin concentrations in critically ill patients: a population pharmacokinetic analysis. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2017;49:204–11.

Nicolau DP, Freeman CD, Belliveau PP, Nightingale CH, Ross JW, Quintiliani R. Experience with a once-daily aminoglycoside program administered to 2,184 adult patients. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1995;39:650–5.

Barclay ML, Kirkpatrick CM, Begg EJ. Once daily aminoglycoside therapy: is it less toxic than multiple daily doses and how should it be monitored. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1999;36:89–98.

Sawchuk RJ, Zaske DE, Cipolle RJ, Wargin WA, Strate RG. Kinetic model for gentamicin dosing with the use of individual patient parameters. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1977;21:362–9.

Cockcroft DW, Gault MH. Prediction of creatinine clearance from serum creatinine. Nephron. 1976;16:31–41.

Green B, Duffull SB. What is the best size descriptor to use for pharmacokinetic studies in the obese? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2004;58:119–33.

Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, Stevens LA, Zhang YL, Hendriksen S, et al. Using standardized serum creatinine values in the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145:247–54.

Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, Zhang YL, Castro AF 3rd, Feldman HI, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:604–12.

Sagwa EL, Nunurai R, Mavhunga F, Rennie T, Leufkens HGM, Mantel-Teeuwisse AK. Comparing amikacin and kanamycin-induced hearing loss in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis treatment under programmatic conditions in a Namibian retrospective cohort. BMC Pharmacol Toxicol. 2016;16:36.

Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually transmitted diseases treatment guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2015;64:1–137.

Triggs E, Charles B. Pharmacokinetics and therapeutic drug monitoring of gentamicin in the elderly. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1999;37:331–41.

Kirkpatrick CM, Duffull SB, Begg EJ. Pharmacokinetics of gentamicin in 957 patients with varying renal function dosed once daily. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1999;47:637–43.

Levey AS, Inker LA. Assessment of glomerular filtration rate in health and disease: a state of the art review. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017;102:405–19.

Grub A. Cystatin C- and creatinine-based GFR-prediction equations for children and adults. Clin Biochem. 2011;44:501–2.

Glaser N, Deckert A, Phiri S, Rothenbacher D, Neuhann F. Comparison of various equations for estimating GFR in Malawi: how to determine renal function in resource limited settings? PLoS ONE. 2015;10:.e01304.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

None.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Singu, B.S., Mubita, M., Thikukutu, M.M. et al. Monitoring of gentamicin serum concentrations in obstetrics and gynaecology patients in Namibia. Int J Clin Pharm 40, 520–525 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-018-0626-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-018-0626-8