Abstract

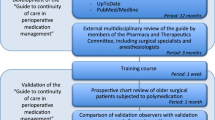

Background Surgical adverse events constitute a considerable problem. More than half of in-hospital adverse events are related to a surgical procedure. Medication related events are frequent and partly preventable. Due to the complexity and multidisciplinary nature of the surgical process, patients are at risk for drug related problems. Consistent drug management throughout the process is needed. Objective The aim of this study was to develop an evidence—based bedside tool for drug management decisions during the pre- and postoperative phase of the surgical pathway. Setting Tool development study performed in an academic medical centre in the Netherlands involving an expert panel consisting of a surgeon, a clinical pharmacist and a pharmacologist, all experienced in quality improvement. Method Relevant medication related problems and critical pharmacotherapeutic decision steps in the surgical process were identified and prioritised by a team of experts. The final selection comprised undesirable effects or unintended outcomes related to surgery (e.g. pain, infection) and comorbidity related hazards (e.g. diabetes, cardiovascular diseases). To guide patient management, a list of bedside surgical drug rules was developed using international evidence-based guidelines. Main outcome measure 55 bedside drug rules on 6 drug categories, specifically important for surgical practice, were developed: pain, respiration, infection, diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and anticoagulation. Results A total of 29 evidence—based guidelines were used to develop the Bedside Surgical Drug Rules tool. This tool consist of practical tables covering management regarding (1) the most commonly used drug categories during surgery, (2) comorbidities that require dosing adjustments and, (3) contra-indicated drugs in the perioperative period. Conclusion An evidence-based approach provides a practical basis for the development of a bedside tool to alert and assist the care providers in their drug management decisions along the surgical pathway.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Leape LL, Brennan TA, Laird N, Lawthers AG, Localio AR, Barnes BA, et al. The nature of adverse events in hospitalized patients. Results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study II. N Engl J Med. 1991;324(6):377–84.

Morimoto T, Gandhi TK, Seger AC, Hsieh TC, Bates DW. Adverse drug events and medication errors: detection and classification methods. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13(4):306–14.

De Vries EN, Ramrattan MA, Smorenburg SM, Gouma DJ, Boermeester MA. The incidence and nature of in-hospital adverse events: a systematic review. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17:216–23.

Kanjanarat P, Winterstein AG, Johns TE, Hatton RC, Gonzalez-Rothi R, Segal R. Nature of preventable adverse drug events in hospitals: a literature review. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2003;60(17):1750–9.

Bates DW, Miller EB, Cullen DJ, Burdick L, Williams L, Laird N, et al. Patient risk factors for adverse drug events in hospitalized patients. ADE Prevention Study Group. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(21):2553–60.

De Vries EN, Prins HA, Crolla RMPH, den Outer AJ, van Andel G, van Helden SH, et al. Effect of a comprehensive surgical safety system on patient outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(20):1928–37.

Borowitz SM, Waggoner-Fountain LA, Bass EJ, Sledd RM. Adequacy of information transferred at resident sign-out (in-hospital handover of care): a prospective survey. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17(1):6–10.

Arora V, Johnson J, Lovinger D, Humphrey HJ, Meltzer DO. Communication failures in patient sign-out and suggestions for improvement: a critical incident analysis. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(6):401–7.

de Boer M, Boeker EB, Ramrattan MA, Kiewiet JJ, Dijkgraaf MG, Boermeester MA, et al. Adverse drug events in surgical patients: an observational multicentre study. Int J Clin Pharm. 2013;35(5):744–52.

Kennedy JM, van Rij AM, Spears GF, Pettigrew RA, Tucker IG. Polypharmacy in a general surgical unit and consequences of drug withdrawal. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2000;49(4):353–62.

Greenberg CC, Regenbogen SE, Studdert DM, Lipsitz SR, Rogers SO, Zinner MJ, et al. Patterns of communication breakdowns resulting in injury to surgical patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204(4):533–40.

Griffen FD, Stephens LS, Alexander JB, Bailey HR, Maizel SE, Sutton BH, et al. The American College of Surgeons’ closed claims study: new insights for improving care. J Am Coll Surg. 2007;204(4):561–9.

de Vries EN, Hollmann MW, Smorenburg SM, Gouma DJ, Boermeester MA. Development and validation of the SURgical PAtient Safety System (SURPASS) checklist. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(2):121–6.

Marang-van de Mheen PJ, van Duijn-Bakker N, Kievit J. Adverse outcomes after discharge: occurrence, treatment and determinants. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17(1):47–52.

Dankelman J, Grimbergen CA. Systems approach to reduce errors in surgery. Surg Endosc. 2005;19(8):1017–21.

Thomas EJ, Studdert DM, Burstin HR, Orav EJ, Zeena T, Williams EJ, et al. Incidence and types of adverse events and negligent care in Utah and Colorado. Med Care. 2000;38(3):261–71.

Wilson RM, Runciman WB, Gibberd RW, Harrison BT, Newby L, Hamilton JD. The quality in Australian health care study. Med J Aust. 1995;163(9):458–71.

Expert Group On Safe Medication Practices: Creation of a better medication safety culture in Europe: Building up safe medication practices. Strasbourg, France: 2006.

Macintyre PE, Schug SA, Scott DA, Visser EJ, Walker SM; APM:SE Working Group of the Australian and New Zealand College of Anaesthetists and Faculty of Pain Medicine. Acute pain management: scientific evidence. 3rd ed. Melbourne: ANZCA & FPM; 2010.

NHS Quality Improvement Scotland 2004 Postoperative Pain Management. ISBN: 1-84404-285-7 First published June 2004.

NHS-NPC Cardiovascular and gastrointestinal safety of NSAIDs. MeReC extra issue no 30; 2007.

NICE CKS. NSAIDs—prescribing issues. www.cks.nice.org.uk/nsaids-prescribing-issues.

Doshi D, Foex B, Body R, Mackway-Jones K. Guideline for the management of acute allergic reaction. In: GEMNET 2009.

Celli BR, MacNee W, Agusti A, Anzueto A, Berg B, Buist AS, Calverley PMA, Chavannes N, Dillard T, Fahy B, Fein A, Heffner J, Lareau S, Meek P, Martinez F, McNicholas W, Muris J, Austegard E, Pauwels R, Rennard S, Rossi A, Siafakas N, Tiep B, Vestbo J, Wouters E, ZuWallack R. Standards for the diagnosis and treatment of patients with COPD: a summary of the ATS/ERS position paper. Eur Respir J. 2004 Jun;23(6):932–46.

Haeck PC, Swanson JA, Iverson RE, Lynch DJ, ASPS Patient Safety Committee. Evidence-based patient safety advisory: patient assessment and prevention of pulmonary side effects in surgery. Part 2. Patient and procedural risk factors. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(4 Suppl):57S–67S.

Haeck PC, Swanson JA, Iverson RE, Lynch DJ, ASPS Patient Safety Committee. Evidence-based patient safety advisory: patient assessment and prevention of pulmonary side effects in surgery. Part 1. Obstructive sleep apnea and obstructive lung disease. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124(4 Suppl):45S–56S.

Surgical site infection: Prevention and treatment of surgical site infection. In: National Collaborating Centre for Women’s and Children’s health. Clinical Guideline 2008. ISBN: 978-1-904752-69-1.

Perioperative Protocol. In: Institute for Clinical Systems Improvement. Guidelines 2010. https://www.icsi.org/guidelines__more/catalog_guidelines_and_more/catalog_guidelines/catalog_patient_safetyreliability_guidelines/perioperative/.

Antibiotic Prophylaxis in Surgery. Adapted from Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network. SIGN 104: A national practical guideline. Edinburgh: SIGN.

Steinberg JP, Braun BI, Hellinger WC, Kusek L, Bozikis MR, Bush AJ, et al, Trial to Reduce Antimicrobial Prophylaxis Errors (TRAPE) Study Group. Timing of antimicrobial prophylaxis and the risk of surgical site infections: results from the Trial to Reduce Antimicrobial Prophylaxis Errors. Ann Surg. 2009;250(1):10–6.

Kao LS, Meeks D, Moyer VA, Lally KP. Peri-operative glycaemic control regimens for preventing surgical site infections in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;8(3):CD006806.

Anderson DJ, Kaye KS, Classen D, Arias KM, Podgorny K, Burstin H, et al. Strategies to prevent surgical site infections in acute care hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2008;29(Suppl 1):S51–61.

Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, Lockhart PB, Baddour LM, Levison M, et al., American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee, American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, American Heart Association Council on Clinical Cardiology, American Heart Association Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Prevention of infective endocarditis: guidelines from the American Heart Association: a guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis, and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. Circulation. 2007;116(15):1736–54. Epub 2007 Apr 19. Erratum in: Circulation. 2007;116(15):e376–7.

Prevention of surgical site infections. In: Prevention and Control of healthcare associated infections in Massachusetts, part-1: Final recommendations of the expert panel; JSI research and training institute; 2008;61–8.

National electronic Library for Medicines http://www.diabetes.org.uk/Documents/Professionals/Reportsandstatistics/Managementofadultswithdiabetesundergoingsurgeryandelectiveprocedures-improvingstandards.pdf. NHS Diabetes. 2011.

Joshi GP, Chung F, Vann MA, Ahmad S, Gan TJ, Goulson DT, et al.; Society for Ambulatory Anesthesia. Society for Ambulatory Anesthesia consensus statement on perioperative blood glucose management in diabetic patients undergoing ambulatory surgery. Anesth Analg. 2010;111(6):1378–87.

Watson B, Smith I, Jennings A, Wilson SF. Day surgery & the diabetic patient. Guidelines for the assessment and management of diabetes in day surgery patients. In: British association of day surgery. Working group 2nd Edition 2004.

Bonow RO, Carabello BA, Chatterjee K, de Leon AC Jr, Faxon DP, Freed MD, et al., 2006 Writing Committee Members, American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force. 2008 Focused update incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2006 guidelines for the management of patients with valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the 1998 Guidelines for the Management of Patients With Valvular Heart Disease): endorsed by the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. Circulation. 2008;118(15):e523–61.

Habib G, Hoen B, Tornos P, Thuny F, Prendergast B, Vilacosta I, et al., ESC Committee for Practice Guidelines. Guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of infective endocarditis (new version 2009): the Task Force on the Prevention, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Infective Endocarditis of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC). Endorsed by the European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases (ESCMID) and the International Society of Chemotherapy (ISC) for Infection and Cancer. Eur Heart J. 2009;30(19):2369–413.

American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines, American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Rhythm Society, Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society for Vascular Medicine, Society for Vascular Surgery, Fleisher LA, Beckman JA, Brown KA, Calkins H, Chaikof EL, Fleischmann KE, et al. ACCF/AHA focused update on perioperative beta blockade incorporated into the ACC/AHA 2007 guidelines on perioperative cardiovascular evaluation and care for noncardiac surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;54(22):e13–e118.

Task Force for Preoperative Cardiac Risk Assessment and Perioperative Cardiac Management in Non-cardiac Surgery; European Society of Cardiology (ESC), Poldermans D, Bax JJ, Boersma E, De Hert S, Eeckhout E, Fowkes G, et al. Guidelines for pre-operative cardiac risk assessment and perioperative cardiac management in non-cardiac surgery. Eur Heart J. 2009;30(22):2769–812.

Dworkin RH, O’Connor AB, Backonja M, Farrar JT, Finnerup NB, Jensen TS, et al. Pharmacologic management of neuropathic pain: evidence-based recommendations. Pain. 2007;132(3):237–51.

De Caterina R, Husted S, Wallentin L, Agnelli G, Bachmann F, Baigent C, et al. Anticoagulants in heart disease: current status and perspectives. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(7):880–913.

Levy JH, Key NS, Azran MS. Novel oral anticoagulants: implications in the perioperative setting. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(3):726–45.

Douketis JD, Berger PB, Dunn AS, Jaffer AK, Spyropoulos AC, Becker RC, et al. American College of Chest Physicians. The perioperative management of antithrombotic therapy: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest. 2008;133(Suppl):299S–339S.

O’Riordan JM, Margey RJ, Blake G, O’Connell PR. Antiplatelet agents in the perioperative period. Arch Surg. 2009;144(1):69–76; discussion 76.

Geerts WH, Bergqvist D, Pineo GF, Heit JA, Samama CM, Lassen MR, et al. American College of Chest Physicians. Prevention of venous thromboembolism: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th Edition). Chest. 2008;133(6 Suppl):381S–453S.

Kaboli PJ, Hoth AB, McClimon BJ, Schnipper JL. Clinical pharmacists and inpatient medical care: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(9):955–64.

Kucukarslan SN, Peters M, Mlynarek M, Nafziger DA. Pharmacists on rounding teams reduce preventable adverse drug events in hospital general medicine units. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163(17):2014–8.

Bates DW, Cullen DJ, Laird N, Petersen LA, Small SD, Servi D, et al. Incidence of adverse drug events and potential adverse drug events. Implications for prevention. ADE Prevention Study Group. JAMA. 1995;274(1):29–34.

Lazarus HM, Fox J, Evans RS, Lloyd JF, Pombo DJ, Burke JP, et al. Adverse drug events in trauma patients. J Trauma. 2003;54(2):337–43.

Hoonhout LH, de Bruijne MC, Wagner C, Asscheman H, van der Wal G, van Tulder MW. Nature, occurrence and consequences of medication-related adverse events during hospitalization: a retrospective chart review in the Netherlands. Drug Saf. 2010 Oct 1;33(10):853–64.

Wyld R, Nimmo WS. Do patients fasting before and after operation receive their prescribed drug treatment? Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 1988;296(6624):744.

Duthie DJ, Montgomery JN, Spence AA, Nimmo WS. Concurrent drug therapy in patients undergoing surgery. Anaesthesia. 1987;42(3):305–6.

Brennan TA, Leape LL, Laird NM, Hebert L, Localio AR, Lawthers AG, et al.; Harvard Medical Practice Study I. Incidence of adverse events and negligence in hospitalized patients: results of the Harvard Medical Practice Study I. 1991. Qual Saf Health Care. 2004;13(2):145–51; discussion 151–2.

Gawande AA, Thomas EJ, Zinner MJ, Brennan TA. The incidence and nature of surgical adverse events in Colorado and Utah in 1992. Surgery. 1999;126(1):66–75.

Griffin FA, Classen DC. Detection of adverse events in surgical patients using the Trigger Tool approach. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17(4):253–8.

Acknowledgments

We are very grateful for the cooperation and input of the clinical pharmacists, the pharmacologists and the consulting surgeons for their input in the development of the surgical drug rules.

Funding

This study was made possible by funding of ZonMw, The Netherlands Organization for Health Research and Development (Project Number 170882706).

Conflicts of interest

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Ramrattan, M.A., Boeker, E.B., Ram, K. et al. Evidence based development of bedside clinical drug rules for surgical patients. Int J Clin Pharm 36, 581–588 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-014-9941-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-014-9941-x