Abstract

We use a heterogeneous panel structural VAR approach to study the role of international financial integration in determining the effectiveness of monetary policy under different exchange rate regimes. In particular, we use the extent to which a country’s monetary policy is able to create temporary deviations from uncovered interest parity as a policy-relevant measure of the degree to which the country is effectively integrated with international financial markets, and then correlate this measure to our estimates of the ability of monetary policy to induce temporary movements in commercial bank lending rates. We find that regardless of whether a country pursues fixed or floating exchange rates, the impact of monetary policy shocks on bank lending rates is diminished as the country becomes financially more integrated with the world economy. This is a direct implication of Mundell’s trilemma for countries with fixed exchange rates, but not for floaters. For floaters, we find that the weaker effects on domestic interest rates under high integration are accompanied with stronger effects on the exchange rate. This also holds true for monetary shocks originating in “core” countries. These results provide a possible reconciliation between Rey’s “dilemma” and Mundell’s famous trilemma: because higher financial integration increases exchange rate volatility in response to foreign monetary shocks, countries in the periphery that seek to avoid such volatility are more likely to pursue monetary policies that shadow those of the core as they become more financially integrated with the core.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See, for example, Klein and Shambaugh (2015) as well as Aizenman et al. (2016). Using an alternative measure of financial integration, Bekaert and Mehl (2017) also found support for the proposition that a positive association has continued to exist between exchange rate flexibility and monetary autonomy even as financial integration has increased

We focus on commercial bank lending rates as our indicator of market interest rates in order to expand and diversify our country sample, because commercial bank lending rates are a key channel for monetary transmission both for countries that set a policy rate and for those that target a monetary aggregate, which remains a common practice in many low-income countries of the periphery.

The use of structural VARs to study the effect of monetary policy on excess returns is well established in the more conventional time series context, including among others Eichenbaum and Evans (1995), Cushman and Zha (1997) for the case of Canada, Brischetto and Voss (1999) for the case of Australia, and Kim and Roubini (2000) for the case of each of the G-6 countries.

See Pedroni (2013) for further details.

Notice that what we are capturing in ε3,t are shocks to the economy that allow the nominal money base to change in the long run, but do not cause the nominal interest rate to change in the long run. Consequently, unless the economy is superneutral, changes in the central bank’s inflation target would be reflected in ε2,t, rather than in ε3,t. Thus, our identification scheme controls for changes to a central bank’s inflation target via ε2,t so that ε3,t. captures monetary policy events that move the money base, but do not move either the inflation rate nor the real interest rate in the long run. By contrast, if we were interested in capturing both changes to an inflation target and our current monetary policy events together in ε3,t, this could be accomplished by using the real interest rate in the Z2,t position.

For example, a large class of open-economy DSGE models imposes continuous UIP while incorporating a wide range of both real and nominal shocks. See, for example, Smets and Wouters (2007).

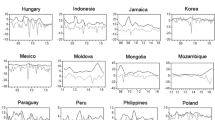

The countries in our sample consisted of Bulgaria, Canada, Cyprus, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Hungary, Iceland, Italy, Jamaica, Japan, Korea, Latvia, Lithuania, Malaysia, Malta, Nepal, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Poland, Samoa, the Slovak Republic, South Africa, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Thailand, the United Kingdom, and Venezuela.

In the working paper version of this paper, we describe a version of the standard textbook Dornbusch model that is modified to incorporate varying degrees of financial integration. As shown there, the model does not make unambiguous predictions on this issue.

It is worth noting that four quarters following the shock, the relationship flips, becoming negative and statistically significant for a brief period. This is likely due to the fact that, as seen in the lower left panel of Figure 5, the nominal exchange rate briefly overshoots its steady state value around this quarter, substantially for at least the top quartile of country responses, and to a lesser extent for the top 50 percentile of country responses.

References

Aizenman J, Chinn MD, Ito H (2016) Monetary policy spillovers and the trilemma in the new Normal: periphery country sensitivity to Core country conditions. J Int Money Financ 68:298–330

Bekaert G. and A. Mehl (2017), “On the global financial market integration “swoosh” and the trilemma,” NBER Working Paper 23124 (February)

Brischetto, Andrea and Graham Voss (1999), “A structural vector autoregression model of monetary policy in Australia,” Reserve Bank of Australia Research Discussion Paper 1999-11

Cushman DO, Zha T (1997) Identifying monetary policy in a small open economy under flexible exchange rates. J Monet Econ 39:433–448

Eichenbaum M, Evans CL (1995) Some empirical evidence on the effects of monetary policy on exchange rates. Q J Econ 110:975–1009

Kim Y, Roubini N (2000) Exchange rate anomalies in industrial countries: a solution with a structural VAR approach. J Monet Econ 45:561–586

Klein M, Shambaugh J (2015) Rounding the corners of the policy trilemma: sources of monetary policy autonomy. Am Econ J Macroecon 7(4):33–66

Mishra P, Montiel PJ, Pedroni P, Spilimbergo A (2014) Monetary policy and Bank lending rates in low-income countries: heterogeneous panel estimates. J Dev Econ 111:117–131

Pedroni P (2013) Structural Panel VARs. Econometrics 1:180–206

Rey H (2015a) Dilemma not trilemma: the global financial cycle and monetary policy Independence. NBER Working Paper 21162

Rey, Helene (2015b), “International channels of transmission of monetary policy and the Mundellian trilemma,” Working paper, London Business School

Smets F, Wouters R (2007) Shocks and frictions in US business cycles: a Bayesian DSGE approach. Am Econ Rev 93(3):586–606

Acknowledgements

We thank Andy Berg for helpful comments and are grateful to the DFID Research Project LICs for financial support. An earlier draft version of this paper was circulated with the title “Exchange Rates, Financial Integration and Monetary Transmission: A Structurally Identified Heterogeneous Panel VAR Approach.”

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Montiel, P.J., Pedroni, P. Trilemma-Dilemma: Constraint or Choice? Some Empirical Evidence from a Structurally Identified Heterogeneous Panel VAR. Open Econ Rev 30, 1–18 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-018-9516-x

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-018-9516-x