Abstract

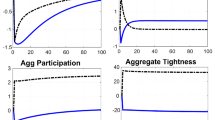

In this paper, we model the assumption of imperfect labor mobility across sectors in the New Open-Economy Macroeconomics framework to assess its impact on output, inflation, and welfare. Following a permanent home monetary expansion in a small open economy, we find that the above-mentioned assumption leads to: (i) less expansionary effects on (traded) output in the short term, although also less contractionary in the long term; (ii) lower short-term inflation but higher in the long term; and (iii) less intertemporal welfare, with even a ‘beggar thyself’ problem being possible.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The role of relative price dynamics in monetary policy shocks is highlighted in, among others, Bils et al (2003).

Although the assumption of an “internationally traded bond denominated in terms of the traded goods” could be changed, in the sense of considering a variety of assets with different denominations (for instance, traded goods which can be exchanged for nontraded goods), most contributions in the literature assume such an assumption for two main reasons: firstly, for analytical simplicity and secondly to capture the fact that a substantial number of less developed countries link their foreign debt to their exports.

We adapt the approach of Casas (1984) to this framework.

This means that we assume that labor has not cost of reallocating within each sector, so that wages and hours worked in different firms of the same sector will be same. Therefore, in line with empirical evidence shown in Davis and Haltiwanger (1991), we assume that the difference of wages and hours is larger between, than within, sectors. However, note that if labor had no costs of moving across sectors (if ε tends to infinity), households would set the same wage in both sectors (W T = W N ). This is a difference from others papers that model the imperfect intersectoral labor mobility, such as Agénor and Santaella (1998). In their model, the case of perfect mobility of labor is not sufficient to establish equality between sectoral wage rates, because wages in the traded good sector are based on efficiency factors.

This equation is obtained by taking into account that: \( \hat C - \widehat{\bar C} = \widehat{\bar P} - \hat P - \left( {{{\widehat{\bar P}}_T} - {{\hat P}_T}} \right) \)

Since firms in the traded good sector are price takers and accordingly cannot pass on higher wages to prices.

References

Agénor PR, Santaella JA (1998) Efficiency wages, disinflation and labor mobility. J Econ Dynam Control 22:267–291

Altig D, Christiano LJ, Eichenbaum M, Linde J (2005) Firm-specific capital, nominal rigidities and the business cycle. NBER Working Paper No. 11034

Ball L, Romer D (1990) Real rigidities and the non-neutrality of money. Rev Econ Stud 57:183–204

Basu S, Fernald JG (1997) Returns to scale in U.S. production: estimates and implications. J Polit Econ 105:249–283

Betts C, Devereux M (2000) Exchange rate dynamics in a model of pricing-to-market. J Int Econ 50:215–244

Bils MP, Klenow PJ, Kryvtsov O (2003) Sticky prices and monetary policy shocks. Fed Reserve Bank Minneapolis Q Rev 27:2–9

Blanchard OJ, Kiyotaki N (1987) Monopolistic competition and the effects aggregate demand. Am Econ Rev 77:647–666

Carlstrom CT, Fuerst TS, Ghironi F, Hernandez K (2006). Relative price dynamics and the aggregate economy, unpublished manuscript

Casas FR (1984) Imperfect factor mobility: a generalization and synthesis of two-sector models of international trade. Can J Econ 17:747–761

Christiano LJ (2004). Firm-specific capital and aggregate inflation dynamics in Woodford’s model. Working paper. Northwestern University

Corsetti G, Pesenti P (2001) Welfare and macroeconomic interdependence. Q J Econ 116:421–445

Davis SJ, Haltiwanger J (1991) Wage dispersion between and within U.S. manufacturing plants, 1963–1986, NBER Working Paper No. 3722

Davis SJ, Haltiwanger J (2001) Sectoral job creation and destruction responses to oil price changes. J Monet Econ 48:465–512

De Paoli B (2009) Monetary policy and welfare in a small open economy. J Int Econ 77:11–22

Hau H (2000) Exchange rate determination: the role of factor price rigidities and nontradables. J Int Econ 50:421–448

Helwege J (1992) Sectoral shifts and interindustry wage differentials. J Labor Econ 10:55–84

Horvath M (2000) Sectoral shocks and aggregate fluctuations. J Monet Econ 45:69–106

Huang KXD (2006) Specific factors meet intermediate inputs: Implications for the persistence problem. Rev Econ Dyn 9:483–507

Keane MP (1993) Individual heterogeneity and interindustry wage differentials. J Hum Resour 28:134–161

Krueger A, Summers LH (1998) Efficiency wages and the interindustry wage structure. Econometrica 56:259–293

Lane PR (1997) Inflation in open economies. J Int Econ 42:327–347

Obstfeld M, Rogoff K (1995) Exchange rate dynamics redux. J Polit Econ 103:624–660

Stockman A, Tesar L (1995) Tastes and technology in a two-country model of the business cycle: Explaining international comovement. Am Econ Rev 85:168–185

Tille C (2001) The role of consumption substitutability in the international transmission of monetary shocks. J Int Econ 53:421–444

Woodford M (2003) Interest and prices: Foundation of a Theory of Monetary Policy. Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The authors wish to thank two anonymous referees for helpful comments and suggestions.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Garcia-Cebro, J.A., Varela-Santamaria, R. Imperfect Intersectoral Labor Mobility and Monetary Shocks in a Small Open Economy. Open Econ Rev 22, 613–633 (2011). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-009-9138-4

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11079-009-9138-4