Abstract

Palauan (Austronesian) displays a pattern of differential object marking that is limited to the imperfective aspect. In the imperfective, human and/or specific objects are overtly marked. In the perfective aspect, no objects are overtly marked. Conversely, objects in the perfective aspect are cross-referenced by agreement morphology on the verb, while objects in the imperfective aspect never are. I argue that this pattern of aspect-conditioned differential object marking provides support for the position that the phenomenon is best analyzed as arising due to the result of satisfying exceptional licensing requirements enforced by a subset of noun phrases (Kalin 2014).

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

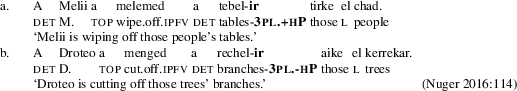

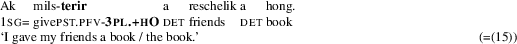

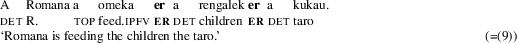

Glossing of Palauan data varies widely from source to source. In an effort to maintain uniform glossing throughout this paper, despite reliance on many sources, I employ the Leipzig Glossing Rules. Supplementing the Leipzig Glossing Rules, the following abbreviations are utilized: =—(realis) subject clitic; ±h—human/non-human; l—linker; O—(perfective) object agreement; P—possessor agreement; p—preposition; S—(irrealis) subject agreement. Also, I have regularized the representation of the glottal stop [ʔ] as ch, despite variation in the source material. This is the orthographic standard (Nuger 2016: 307–308).

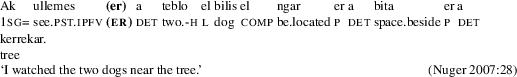

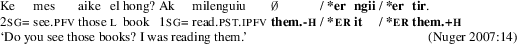

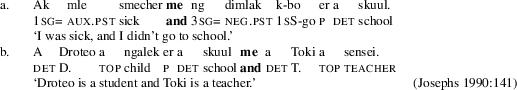

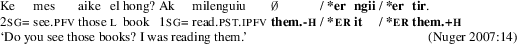

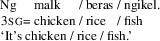

Nuger (2007) observes that speakers’ judgments vary regarding er-marking on direct objects that refer to common household animals, e.g. dogs and pigs, (i) (see also Josephs 1997).

-

(i)

If common household animals are treated like human objects with respect to er-marking, the direct object in (i) bears er, because all human objects are er-marked. If common household animals are treated like non-human objects with respect to er-marking, the direct object in (i) will not bear er, because plural non-human objects are not er-marked.

Nuger does not discuss how these speakers treat common household animal direct objects with respect to object agreement. If speakers treat such objects as human-like for the purposes of er-marking, we expect them to treat the same objects as human-like for the purposes of object agreement, utilizing the 3rd person plural human object morpheme -(e)terir. If speakers treat such objects as non-human for the purposes of er-marking, we expect them to treat the same objects as non-human for the purposes of object agreement, realizing no (overt) agreement morphology.

Josephs (1997:69) does observe that speakers’ judgments vary as to whether or not common household animals can control subject agreement. This variation may suggest that object agreement should behave similarly, as predicted.

-

(i)

The absence of er-marking on embedded subjects in (16) is one factor that distinguishes Palauan DOM from Spanish DOM. Spanish DOM marks human specific direct objects with a. Furthermore, all subjects embedded under ECM/SOR predicates are also marked with a (e.g. Ormazabal and Romero 2013). Palauan, however, retains featural sensitivity in er-marking on embedded subjects. This fact will become important for disambiguating competing models of DOM in Sects. 4–5.

Nuger (2016) agrees with Georgopoulos’s treatment of object agreement morphology, but claims that the status of subject cross-referencing morphology is less clear. He argues that such morphology can surface either as a clitic or as ϕ-agreement based on mood. Clitics are employed in the realis mood; ϕ-agreement in the irrealis mood.

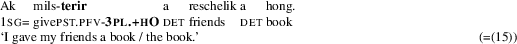

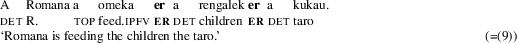

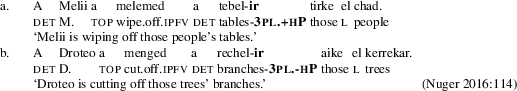

Another mismatch between er-marking and ϕ-agreement is illustrated in (ii) and (iii), repeating data from (9) and (15).

-

(ii)

-

(iii)

In (ii), only agreement with the indirect object is registered on the verb. However in (iii), both internal arguments are er-marked. In this instance, a nominal whose featural specification is not overtly reflected by object agreement morphology in the perfective does trigger er-marking in the imperfective. This mismatch does not necessarily motivate a split in the source of the two phenomena, both arguments of the double object construction might be targeted by ϕ-agreement in (ii) via Multiple Agree. Conditions on the exponence of the result of multiple ϕ-agreement relations could then limit overt relation to only one of the two relations (e.g. Anagnostopoulou 2005; Nevins 2011; see also Hiraiwa 2001, 2005). Unlike, object agreement, er-marking faces no similar problem of exponence, resulting in multiple er-marked objects in (iii). I return to the issue of Multiple Agree in Sect. 4.3.

-

(ii)

This is not to say that additional structure cannot be added to derive perfective interpretations (see Demirdache and Uribe-Etxebarria 2000, 2007). A more accurate characterization might be that the ‘simplest’ perfective construction will be simpler than the ‘simplest’ non-perfective construction, but more research is needed to determine if this is always the case cross-linguistically.

A closely related alternative would be to posit that perfective \(\mathit {v}^{0}\), like imperfective \(\mathit {v}^{0}\), does select for an \(\mbox{Asp}_{s}\)P. Crucially, unlike the \(\mbox{Asp}_{s}\)P of imperfective clauses, this \(\mbox{Asp}_{s}\)P would need to be non-phasal to allow for probing from \(\mathit {v}^{0}\) to target the DP-complement to V0. This analysis is problematic in that it would posit the phasal status of a given head/projection comes and goes depending on the featural/semantic specification of another head, namely \(\mathit {v}^{0}\). Moreover, Sect. 3.3.2 demonstrates that the proposed selectional variability is independently motivated. I thank two anonymous reviews for valuable discussion concerning this point.

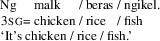

Of these two possibilities, it is more likely that 3rd person is a ‘real’ person. This is because mass nouns, which by hypothesis have no number, nevertheless trigger canonical 3rd person singular agreement, as seen in example (22).

The clitic doubling account forces the position that non-human plural arguments are doubled by a null clitic. Recall that the only arguments not cross-referenced by overt morphology in perfective clauses are non-human plurals (12). I know of no language that has been proposed to employ null clitics, but they could in principle exist. The position is especially plausible in Palauan where non-human plural free pronouns are also obligatorily null (17). This is illustrated below:

-

(iv)

If the clitic is taken to be a pronominal copy of the nominal it doubles (e.g. Anagnostopoulou 2003), it, in fact, follows that the non-human plural clitics would be null.

-

(iv)

A plausible alternative would be to model \(\mbox{Asp}_{\mathit {v}}^{0}\) as an independent head, separate from \(\mathit {v}^{0}\). On this view, \(\mbox{Asp}_{\mathit {v}}^{0}\) heads in Palauan are always null, but they select morphologically overt forms of \(\mathit {v}^{0}\) (Nuger 2016).

The present analysis is highly reminiscent of Béjar and Rezac’s Person Licensing Condition, proposed to explain PCC effects:

-

(v)

Person Licensing Condition (Béjar and Rezac 2003:53)

Interpretable 1st/2nd person features must be licensed by entering into an Agree relation with an appropriate functional category.

As 1st/2nd person arguments are highest on the Definiteness Scale for DOM (1), we could intuitively maintain that all DOM patterns are triggered by ‘extended’ PLC-like statements, and in fact, Rezac’s (2011) treatment of Dependent Case phenomena as an analogue of PCC repairs comes quite close to collapsing PCC and DOM phenomena. Kalin (2014, 2016) acknowledges this connection between PCC and DOM effects, noting that an ‘extended’ PLC approach to DOM faces some complications with respect to the behavior of DOM in Senaya (Neo-Aramaic). Namely, specific objects which trigger DOM can be licensed via ϕ-agreement with auxiliaries, but 1st/2nd person objects cannot. It is not immediately clear if this is should be taken as evidence against an ‘extended’ PLC or an idiosyncrasy of Senaya participant arguments.

-

(v)

It is possible to introduce possessors without er, so long as possessor agreement is realized on the possessum (vi):

-

(vi)

This pattern is strikingly similar to the behavior of direct objects which are either introduced via er-marking or object agreement. However, unlike direct objects, er-marking on possessors occurs regardless of the feature specification of the possessor. For instance, non-human plural objects do not trigger er-marking (8b), but non-human plural possessors are nevertheless introduced with er (50b). I leave further investigation of this connection to future work.

-

(vi)

Coon (2013) suggests that in some languages non-perfective clauses are formed by base-generating PPs in the place of DP objects (e.g. Adyghe, Georgian, Samoan and Warrungu), as opposed to the addition of extra phasal structure within the extended verbal projection. However, given Nuger’s (2016) argument from ECM/SOR we can be sure that Palauan is not such a language.

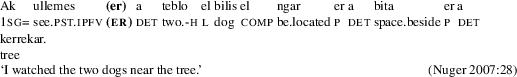

An anonymous reviewer observes that another environment in which er-marking is not attested is on predicative nominals:

-

(vii)

-

(viii)

As expected in the absence of ϕ-agreement, non-human non-specific predicative nominals, (vii), do not display er-marking, but strikingly neither do human predicative nominals, (viii). Similar patterns are found in nearby Micronesian languages, whereby object cross-referencing morphology present in transitive clauses does not cross-reference predicative nominals (see e.g. Benton 1968 on Chuukese and Sohn 1975 on Woleaian). There are at least two ways to explain these facts. First, predicative nominal constructions like perfective constructions may permit canonical nominal licensing, cf. (54). In this case, the human pronoun kau ‘you’ in (54b) would bear [F] and stand in an Agree relationship with a local functional head (possibly Pred0), as [F] is licensed by this head, er-marking is unnecessary (see e.g. Baker 2008). Crucially, unlike pronominal objects in perfective constructions, this licensing relationship neither results in the realization of object ϕ-agreement nor forces the pronominal to be null, cf. (14). This second point of variation is also found in Micronesian languages (see Hattori 2012 for an overview). Alternatively, er-marking may not occur if predicative nominals differ from nominals in argument position in that they lack the functional architecture thought to bear [F]. On this treatment, er-marking would never occur, because the nominals in question need not be licensed. I leave further research into this matter for future work.

-

(vii)

I direct the reader to Rezac (2011) for the details of a cyclicity-obeying approach to P0-Insertion, as well as discussion of other environments in which exceptional licenser insertion occurs.

One might wonder if what I have been referring to as ECM/SOR predicates might in fact be better analyzed as object control or proleptic object constructions. On either of the these alternatives, the behavior of the putative ‘embedded subject’ would be unsurprising, as the argument in question would in fact serve as the object of the matrix clause and only stand in a co-reference relationship with the embedded (null) subject. Despite these prima facie plausible alternatives, there are reasons to doubt their validity. First, Nuger (2010, 2016) demonstrates that the embedded subject does not receive a θ-role from the matrix predicate, suggesting the object control analysis (but not the prolepsis analysis) is not correct. More strikingly, he demonstrates that only when the embedded clause is non-finite does the logical subject of that clause behave as a matrix object, triggering object agreement and appearing adjacent to the matrix verb. If the putative ECM/SOR subject were always base-generated in the matrix clause, we would not expect such sensitivity to finiteness of the embedded clause. A prolepsis account is also ruled out, precisely because er-marking is not uniform (57). As noted in Sect. 4.2, when er acts as an unambiguous preposition it appears regardless of the aspectual specification of the clause, this would be expected if er were to introduce a proleptic argument, contrary to fact. I thank the editor and an anonymous reviewer for helpful discussion of this point.

Josephs (1975) offers an alternative explanation of the degraded example (61b) in terms of sentence processing. He posits that the presence of a singular noun a hong ‘a book’ immediately after the 3rd person human plural object agreement marker is difficult to parse. The evaluation of the validity of this alternative must also be left for future work.

An alternative explanation for the inability to realize er within the coordination would be to treat the coordinator me as a comitative. The comitative P0 could then be seen to license the second ‘conjunct’ directly. There is some reason to reject this position. First, I know of no instance outside of coordination in which me is used. If me were a comitative PP, we would expect it to surface in other positions, e.g. as a VP adjunct. Furthermore, me is able to coordinate non-DP phrases.

-

(ix)

If me were a comitative P0, it would be difficult to explain its ability to select non-DP-complements.

-

(ix)

Woolford (2000) offers an OT syntax approach to DOM in Palauan. As noted in Sect. 2.3, her account is untenable in light of data that demonstrates that singular non-human non-specific subjects trigger ϕ-agreement but not er-marking. I leave it to future research to determine if other OT approaches to Palauan object marking are viable.

See Coon (2013:Sect. 5.4.3) for a discussion of some apparent “counteruniversal” aspect-splits that nevertheless obey the generalization that non-canonical case/agreement patterns are associated with the presence of additional phasal structure.

References

Abney, Steven. 1987. The English noun phrase in its sentential aspect. PhD diss., MIT.

Adger, David, and Daniel Harbour. 2007. Syntax and syncretisms of the person case constraint. Syntax 10: 2–37.

Aissen, Judith. 2003. Differential object marking: Iconicity vs. economy. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 21: 435–483.

Anagnostopoulou, Elena. 2003. The syntax of ditransitives: Evidence from clitics. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Anagnostopoulou, Elena. 2005. Strong and weak person restrictions: A feature checking analysis. In Clitic and affix combinations: Theoretical perspectives, eds. Lorie Heggie and Francisco Ordoñez, 199–235. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Arregi, Karlos, and Andrew Nevins. 2012. Morphotactics: Basque auxiliaries and the structure of spellout. Dordrecht: Springer.

Austin, Peter. 1981. Case marking in Southern Pibara languages. Australian Journal of Linguistics 1: 211–226.

Badecker, William. 2007. A feature principle for partial agreement. Lingua 117: 1541–1565.

Baker, Mark C. 1985. The Mirror Principle and morphosyntactic explanation. Linguistic Inquiry 16: 373–415.

Baker, Mark C. 2008. The syntax of agreement and concord. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Baker, Mark C. 2012. On the relationship of object agreement and accusative case: Evidence from Amharic. Linguistic Inquiry 43: 255–274.

Baker, Mark C. 2015. Case: Its principles and its parameters. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Baker, Mark C., and Nadya Vinokurova. 2010. Two modalities of Case assignment: Case in Sakha. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 28: 593–642.

Béjar, Susanna, and Milan Rezac. 2003. Person licensing and the derivation of PCC effects. In Romance linguistics: Theory and acquisition, eds. Ana Teresa Pérez-Leroux and Yves Roberge, 49–62. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Benton, Richard A. 1968. Substitutes and classifiers in Trukese. PhD diss., University of Hawai’i, Manoa.

Bhatt, Rajesh. 2007. Unaccusativity and case licensing. Talk presented at McGill University.

Bhatt, Rajesh, and Martin Walkow. 2013. Locating agreement in grammar: An argument from agreement in conjunctions. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 31: 951–1013.

Bleam, Tonia. 1999. Leísta Spanish and the syntax of clitic doubling. PhD diss., University of Delaware.

Bobaljik Jonathan David. 1993. On ergativity and ergative unergatives. In Papers on case and agreement II, ed. Colin Phillips. Cambridge: MITWPL.

Bošković, Željko. 2009. Unifying first and last conjunct agreement. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 27: 455–496.

Bossong, Georg. 1991. Differential object marking in Romance and beyond. In New analyses in Romance linguistics, eds. Douglas A. Kibbee and Dieter Wanner, 143–170. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Bybee, Joan L., Revere D. Perkins, and William Pagliuca. 1994. The evolution of grammar. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Capell, Arthur. 1949. A grammar of the language of Palau. Washington DC: Pacific Science Board, National Research Council.

Chomsky, Noam. 1981. Lectures on government and binding: The Pisa lectures. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The minimalist program. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2000. Minimalist inquiries: The framework. In Step by step: Essays on minimalist syntax in honor of Howard Lasnik, eds. Roger Martin, David Michaels, and Juan Uriagereka, 89–155. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Derivation by phase. In Ken Hale: A life in language, ed. Michael Kenstowicz, 1–52. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Comrie, Bernard. 1979. Definite and animate direct objects: A natural class. Linguistica Silesiana 3: 13–21.

Coon, Jessica. 2010. Complementation in Chol (Mayan): A theory of split ergativity. PhD diss., MIT.

Coon, Jessica. 2012. TAM split ergativity. Ms., McGill University.

Coon, Jessica. 2013. Aspects of split ergativity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Coon, Jessica, and Omer Preminger. 2011. Towards a unified account of person splits. In West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 29, eds. Jaehoon Choi et al., 310–318. Somerville: Cascadilla Press.

Coon, Jessica, and Omer Preminger. 2017. Split ergativity is not about ergativity. In The Oxford handbook of ergativity, eds. Jessica Coon, Diane Massam, and Lisa Travis, 226–252. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Croft, William. 1988. Agreement vs. case marking and direct objects. In Agreement in natural language: Approaches, theories, descriptions, eds. Michael Barlow and Charles Ferguson, 159–179. Stanford: CSLI.

Danon, Gabi. 2006. Caseless nominals and the projection of DP. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 24: 977–1008.

Danon, Gabi. 2011. Agreement and DP-internal feature distribution. Syntax 14: 297–317.

Deal Amy Rose. 2009. The origin and content of expletives: Evidence from “selection”. Syntax 12: 285–323.

Demonte, Violeta. 1987. C-command, prepositions, and predications. Linguistic Inquiry 18: 147–157.

Demirdache, Hamida, and Myriam Uribe-Etxebarria. 2000. The primitives of temporal relations. In Step by step: Essays on minimalist syntax in honor of Howard Lasnik, eds. Roger Martin, David Michaels, and Juan Uriagereka, 157–186. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Demirdache, Hamida, and Myriam Uribe-Etxebarria. 2007. The syntax of time arguments. Lingua 117: 330–366.

Diesing, Molly 1992. Indefinities. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Dixon, R. M. W. 1979. Ergativity. Language 55: 59–138.

Dixon, R. M. W. 1994. Ergativity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dyen, Isidore. 1971. Review of Patzold, Die Palau-sprache und ihre Stellung zu anderen indonesischen Sprachen. Journal of the Polynesian Society 80: 247–258.

Enç, Mürvet. 1991. The semantics of specificity. Linguistic Inquiry 22: 1–26.

Flora, Jo-Ann. 1974. Palauan phonology and morphology. PhD diss., University of California, San Diego.

Forker, Diana. 2010. The biabsolutive construction in Nakh-Dagestanian. Ms., Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology.

Gagliardi, Annie, Michael Goncalves, Maria Polinsky, and Nina Radkevich. 2012. The biabsolutive construction in Lak and Tsez. Lingua 150: 137–170.

Georgopoulos, Carol. 1986. Palauan as a VOS language. In FOCAL I: Papers from the Fourth International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics, eds. Paul Geraghty, Lois Carrington, and Stephen Wurm, 187–198. Canberra: Pacific Linguistics.

Georgopoulos, Carol. 1991. Syntactic variables: Resumptive pronouns and Ā binding in Palauan. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Georgopoulos, Carol. 1992. Another look at object agreement. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 22, ed. Kimberley Broderick, 165–177. Amherst: GSLA.

Giannakidou, Anastasia. 2011. Positive polarity items and negative polarity items: Variation, licensing, and compositionality. In Semantics: An international handbook of natural language meaning, eds. Claudia Maienborn, Klaus von Heusinger, and Paul Portner, 1660–1712. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Grimshaw, Jane. 1991. Extended projection. Ms., Brandeis University.

Grimshaw, Jane. 2005. Words and structure. Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Harizanov, Boris. 2014. Clitic doubling at the syntax-morphophonology interface. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 32: 1033–1088.

Harley, Heidi. 2008. On the causative construction. In Handbook of Japanese linguistics, eds. Shigeru Miyagawa and Mamoru Saito, 20–53. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Harley, Heidi. 2013. External arguments and the Mirror Principle: On the distinctness of Voice and v. Lingua 125: 34–57.

Harley, Heidi, and Elizabeth Ritter. 2002. Person and number in pronouns: A feature-geometric analysis. Language 78: 482–526.

Hattori, Ryoko. 2012. Preverbal particles in Pingelapese: A language of Micronesia. PhD diss., University of Hawai’i, Manoa.

Hiraiwa, Ken. 2001. Multiple Agree and the Defective Intervention Constraint in Japanese. In MIT-Harvard Joint Conference, ed. Ora Matushansky, 67–80. Cambridge: MITWPL.

Hiraiwa, Ken. 2005. Dimensions of symmetry in syntax: Agreement and clausal architecture. PhD diss., MIT.

de Hoop, Helen. 1996. Case configuration and noun phrase interpretation. New York: Garland.

de Hoop, Helen, and Andrej Malchukov. 2008. Case-marking strategies. Linguistic Inquiry 39: 565–587.

Johnson, Kyle. 1991. Object positions. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 9: 577–636.

Josephs, Lewis. 1975. Palauan reference grammar. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Josephs, Lewis. 1990. New Palauan-English dictionary. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Josephs, Lewis. 1997. Handbook of Palauan grammar: Volume I. Koror: Ministry of Education, Republic of Palau.

Kalin, Laura. 2014. Aspect and argument licensing in Neo-Aramaic. PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles.

Kalin, Laura. 2016. Licensing and differential object marking: The view from Neo-Aramaic. Ms., University of Connecticut.

Kalin, Laura, and Coppe van Urk. 2014. Aspect splits without ergativity: Agreement asymmetries in Neo-Aramaic. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 33: 659–702.

Karttunen, Lauri. 1969. Discourse referents. In 1969 International conference on computational linguistics, Sweden: Sång-Säby.

Keine, Stefan, and Gereon Müller. 2008. Differential argument encoding by impoverishment. In Scales, eds. Marc Richards and Andrej Malchukov. Vol. 86 of Linguistische Arbeitsberichte, 83–136. Leipzig: Universität Leipzig.

Klein, Elaine C. 1995. Evidence for a “wild” L2 grammar: When PPs rear their empty heads. Applied Linguistics 16: 87–117.

Kornfilt, Jaklin, and Omer Preminger. 2015. Nominative as no case at all: An argument from raising-to-ACC in Sakha. In Workshop on Altaic Formal Linguistics (WAFL) 9, eds. Andrew Joseph and Esra Predolac, 109–120. Cambridge: MITWPL.

Kramer, Ruth. 2014. Clitic doubling or object agreement: The view from Amharic. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 32: 593–634.

Kratzer, Angelika. 1996. Severing the external argument from its verb. In Phrase structure and the lexicon, eds. Johan Rooryck and Laurie Zaring, 109–137. Dordrecht: Springer.

Ladusaw, William. 1979. Polarity sensitivity as inherent scope relations. PhD diss., University of Texas, Austin.

Laka, Itziar. 2006. Deriving split ergativity in the progressive: The case of Basque. In Ergativity: Emerging issues, eds. Alana Johns, Diane Massam and Juvenal Ndayiragije, 173–195. Dordrecht: Springer.

Lasnik, Howard, and Mamoru Saito. 1991. On the subject of infinitives. In Papers from the Twenty-seventh Regional Meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society (CLS), eds. Lise Dobrin, Lynn Nichols, and Rosa Rodriguez, 324–343. Chicago: Chicago: Linguistic Society.

Legate, Julie Anne. 2003. Some interface properties of the phase. Linguistic Inquiry 34: 506–516.

Legate, Julie Anne. 2012. Subjects in Acehnese and the nature of the passive. Language 88: 495–525.

Legate, Julie Anne. 2014. Voice and v: Lessons from Acehnese. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Levin, Theodore. 2015. Licensing without Case. PhD diss., MIT.

Levin, Theodore. 2017. Successive-cyclic case assignment: Korean nominative-nominative case-stacking. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 35: 447–498.

Lidz, Jeffrey. 2006. The grammar of accusative case in Kannada. Language 82: 1–23.

Lochbihler, Bethany. 2012. Aspects of argument licensing. PhD diss., McGill University.

López, Luis. 2012. Indefinite objects: Scrambling, choice functions, and differential marking. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Massam, Diane. 2001. Pseudo noun incorporation in Niuean. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 19: 153–197.

McFadden, Thomas. 2004. The position of morphological case in the derivation: A study on the syntax-morphology interface. PhD diss., University of Pennsylvania.

McGinnis, Martha. 2005. On markedness asymmetries in person and number. Language 81: 699–718.

Merchant, Jason. 2006. Polyvalent case, geometric hierarchies, and split ergativity. In 42nd annual meeting of the Chicago Linguistic Society (CLS), eds. Jackie Bunting et al., 57–76. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

Miyagawa, Shigeru. 1998. (S)ase as an elsewhere causative and the syntactic nature of words. Journal of Japanese Linguistics 16: 67–110.

Moravcsik, Edith. 1978. Agreement. In Universals of human language IV: Syntax, ed. Joseph H. Greenberg, 331–374. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Nevins, Andrew. 2007. The representation of third person and its consequences for person-case effects. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 25: 273–313.

Nevins, Andrew. 2011. Multiple Agree with clitics: Person complementarity vs. omnivorous number. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 29: 939–971.

Norris, Mark. 2014. A theory of nominal concord. PhD diss., University of California, Santa Cruz.

Nuger, Justin. 2007. The case of objects. Syntax qualifying paper. Santa Cruz: University of California.

Nuger, Justin. 2009. On downward-entailing existentials and differential object marking in Palauan. In Austronesian Formal Linguistics Association (AFLA) 16, eds. Sandra Chung et al., 137–151. London: The University of Western Ontario.

Nuger, Justin. 2010. Architecture of the Palauan verbal complex. PhD diss., University of California, Santa Cruz.

Nuger, Justin. 2016. Building predicates. New York: Springer.

Ormazabal, Javier, and Juan Romero. 2013. Differential object marking, case and agreement. Borealis: An International Journal of Hispanic Linguistics 2: 221–239.

Paul, Ileana. 2000. Malagasy clause structure. PhD diss., McGill University.

Pesetsky, David, and Esther Torrego. 2004. Tense, Case, and the nature of syntactic categories. In The syntax of time, eds. Jacqueline Guéron and Jacqueline Lecarme, 495–538. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Polinsky, Maria. 2016. Agreement in Archi from a Minimalist perspective. In Archi: Complexities of agreement in cross-theoretical perspective, eds. Oliver Bond et al., Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Postal, Paul M. 1974. On raising. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Preminger, Omer. 2009. Breaking agreements: Distinguishing agreement and clitic doubling by their failures. Linguistic Inquiry 40: 619–666.

Preminger, Omer. 2011. Agreement as a fallible operation. PhD diss., MIT.

Preminger, Omer. 2014. Agreement and its failures. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Reichenbach, Hans. 1947. Elements of symbolic logic. New York: Macmillan.

Rezac, Milan. 2011. Phi-features and the modular architecture of language. Dordrecht: Springer.

Richards, Norvin. 2010. Uttering trees. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Roberts, Ian. 2010. Agreement and head movement: Clitics, incorporation, and defective goals. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Rodríguez-Mondoñedo, Miguel. 2007. The syntax of objects: Agree and differential object marking. PhD diss., University of Connecticut.

Silverstein, Michael. 1976. Hierarchy of features and ergativity. In Grammatical categories in Australian languages, ed. R. M. W. Dixon, 112–171. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

Smith, Carlota. 1991. The parameter of aspect. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Sohn, Ho-min. 1975. Woleaian reference grammar. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

Sportiche, Dominique. 1998. Partitions and atoms of clause structure. London: Routledge.

Stowell, Timothy. 1981. Origins of phrase structure. PhD diss., MIT.

Szabolcsi, Anna. 1994. The noun phrase. In The syntactic structure of Hungarian, eds. Ferenc Kiefer and Katalin É. Kiss, 179–274. San Diego: Academic Press.

Travis, Lisa. 2000. Event structure in syntax. In Events as grammatical objects: The converging perspectives of lexical semantics and syntax. eds. Carol L. Tenny and James Pustejovsky, 145–185. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Travis, Lisa. 2010. Inner Aspect: The articulation of VP. Dordrecht: Springer.

Torrego, Esther. 1998. The dependencies of objects. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Uriagereka, Juan. 1995. Aspects of the syntax of clitic placement in Western Romance. Linguistic Inquiry 26: 79–123.

Valois, Daniel. 1991. The internal syntax of DP. PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles.

Vendler, Zeno. 1967. Linguistics in philosophy. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Waters, Richard C. 1980. Topicalization and passive in Palauan. Ms., MIT.

Wilson, Helen I. 1972. The phonology and syntax of Palauan verb affixes. PhD diss., University of Hawai’i, Manoa.

Woolford, Ellen. 2000. Object agreement in Palauan: Specificity, humanness, economy and optimality. In Formal issues in Austronesian linguistics, eds. Ileana Paul, Vivianne Phillips, and Lisa Travis, 215–245. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Woolford, Ellen. 2013. Aspect splits and parasitic marking. In Linguistic derivations and filtering: Minimalism and optimality theory, eds. Hans Broekhuis and Ralf Vogel, 166–192. London: Equinox Publishing.

Zwicky, Arnold, and Geoffrey Pullum. 1983. Cliticization vs. inflection: English n’t. Language 59: 502–513.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Michael Yoshitaka Erlewine, Laura Kalin, Jeff Lidz, Caitlin Meyer, David Pesetsky, Masha Polinsky, Omer Preminger and Norvin Richards, the audiences of the West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL) 34, the 91st Annual Meeting of the Linguistic Society of America and the University of Maryland’s S-Lab, and four anonymous NLLT reviewers for helpful comments and discussion. This research was supported in part by Singapore Ministry of Education Academic Research Fund Tier 1 under WBS R-103-000-142-115 “Theory and variation in extraction marking and subject extraction asymmetries”, which is greatly acknowledged. All errors are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Levin, T. On the nature of differential object marking. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 37, 167–213 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-018-9412-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-018-9412-5