Abstract

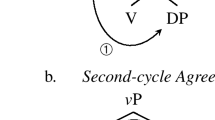

In this paper we propose that probe-goal relations are subject to greater variation than expected, such that both Cyclic Agree and Multiple Agree are possible not only typologically, but also within a single language and a single probe. Cheyenne (Algonquian) has two ways of marking 1st and 2nd person plurality and their conditioning differs between transitives and ditransitives. We propose a hybrid account of agree in order to account for this person/number marking which includes elements of both Cyclic Agree (potentially two probing cycles) and Multiple Agree (multiple simultaneous goals in the first cycle). Evidence against a pure Cyclic Agree account comes from the absence of bleeding effects in transitive forms, which indicates that probing is not always successive cyclic. Evidence against a pure Multiple Agree account comes from the presence of bleeding effects in ditransitive forms, which indicates that all arguments are not always simultaneously probed. Support comes from the properties of other probes in Algonquian and similarities with agreement patterns in other languages, such as Hungarian and Southern Tiwa.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Orthography: V̇ voiceless vowel,

raised high pitch vowel, V́ high pitch vowel,

raised high pitch vowel, V́ high pitch vowel,  mid pitch vowel, and V low pitch vowel. All final vowels are voiceless (not marked, by convention), but their underlying pitch can affect the pitch of other vowels (see Leman 2011 for more details). Abbreviations: 1 = 1st person, 2 = second person, 3 = 3rd person proximate (topical), A = Set A inner suffix, AI = intransitive verb with animate subject, an = animate, appl = applicative, aux = auxiliary, B = Set B inner suffix, dir = direct, exc = exclusive, f.obv = further obviative (non-topical), in = inanimate, inc = inclusive, int = interrogative, inv = inverse, loc = local (forms with only 1st and 2nd persons), neg = negation, obj = object, obv = obviative (non-topical), pass = passive, pl = plural, prt = participle, refl = reflexive, rem.obv = removed obviative, SAP = speech act participant, sg = singular, subj = subject, TA = transitive verb with animate subject and animate object, TI = transitive verb with inanimate object.

mid pitch vowel, and V low pitch vowel. All final vowels are voiceless (not marked, by convention), but their underlying pitch can affect the pitch of other vowels (see Leman 2011 for more details). Abbreviations: 1 = 1st person, 2 = second person, 3 = 3rd person proximate (topical), A = Set A inner suffix, AI = intransitive verb with animate subject, an = animate, appl = applicative, aux = auxiliary, B = Set B inner suffix, dir = direct, exc = exclusive, f.obv = further obviative (non-topical), in = inanimate, inc = inclusive, int = interrogative, inv = inverse, loc = local (forms with only 1st and 2nd persons), neg = negation, obj = object, obv = obviative (non-topical), pass = passive, pl = plural, prt = participle, refl = reflexive, rem.obv = removed obviative, SAP = speech act participant, sg = singular, subj = subject, TA = transitive verb with animate subject and animate object, TI = transitive verb with inanimate object.For an alternate view of theme signs as denoting a change in grammatical function of the subject and object see Rhodes (1994) for Ojibwe.

Since the person prefix, theme sign, and inner suffix each have different and not clearly complementary preferences, we assume that a simpler analysis is one which does not assume that these affixes conspire to index arguments in a certain manner, such as in Anderson (1992).

Note that Set B affixes can appear with an additional -no(t) suffix. See fn. 6 for further discussion.

Although Goddard (2000) posits two sets of objective forms, one based on transitive 3rd person direct objects (w-suffixes) and another on ditransitive 3rd person direct objects (n-suffixes), this distinction is somewhat less clear in Cheyenne. Leman (2011) includes two possibilities for some ditransitive forms, e.g., -ne vs. -none with the same meaning in (i). In transitive forms, the distribution is much less clear with several factors playing some role, e.g., clause type (declarative vs. interrogative), mood (indicative vs. dubitative), and obviation (proximate vs. obviative). Thus, we refer to the common portion across both, e.g., -ne, and leave the analysis of the exact distribution and the role of -no(t) (and its allomorphs, see Fisher et al. 2006 entry -’tov) for further research.

-

(i)

Ná-mêt-am-ó-ne. / Ná-mêt-am-ó-none. 1-give-rem.obv-dir-

/ 1-give-rem.obv-dir-

/ 1-give-rem.obv-dir-  ‘We(

‘We( ) gave her/him/them(rem.obv) to her/him/them(obv).’ (Leman 2011:106)

) gave her/him/them(rem.obv) to her/him/them(obv).’ (Leman 2011:106)

-

(i)

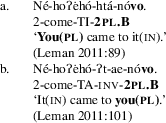

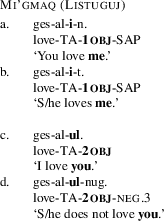

Note that the only thing that changes between the (a) and (b) examples in (2) and (3) are the theme signs, e.g., -atse and -e. See 4.2 for further discussion.

Note that transitive forms with a 1st person plural inclusive argument and another SAP argument do not appear in the grammar (Leman 2011), and so the Set A-B contrast cannot be shown for transitive forms with 1st person plural inclusive arguments. We are uncertain whether the missing transitive forms with 1st person plural inclusive and another SAP argument are a true gap in verbal paradigms or not. They do appear to be a gap in other Algonquian languages (see Valentine 2001; Lochbihler 2012). However, these forms are not crucial for our analysis; if they are possible, we predict Set A allomorphs to appear.

The same pattern is present with transitive verbs with an animate and inanimate argument. This is shown by the lack of contrast in the inner suffix between (ia) and (ib). Here the inanimate 3rd person argument also triggers the Set B inner suffix.

-

(i)

-

(i)

Note that when there are three 3rd persons, there is the possibility for a further obviative form. Although obviative and further obviative are not morphologically distinct in Cheyenne, they are in some Algonquian languages, e.g., Nishnaabemwin Valentine (2001).

We do not take a stance with respect to the position of the person prefix and negative prefix in Table 3, since nothing in our account hinges on a particular analysis.

First, note that we are using [±participant] features in (24) and throughout for ease of exposition. However, nothing in our account crucially hinges on this, as we believe that other feature systems could in principle express the same distinction. Second, note that we do not distinguish between subject and object ϕ-feature bundles, but only between the indexing and conditioning ones, similar to Deal (2015) for Nez Perce. This seems to be a property of specific probes, as the order of the ϕ-feature bundles (subject and object) is relevant for the probe on Voice which is responsible for theme signs (see 4.2).

The data in Leman (2011) does not contradict the Algonquian literature which uniformly assumes that goals are structurally higher than themes. The investigation of underlying structure of ditransitives in Cheyenne is a topic for further research.

We cannot address PCC effects here in any serious detail, but we need to point out that our proposal is perfectly compatible with many major accounts of PCC. If agreement is the source of PCC effects, then we think that lower heads in the verbal domain, e.g., Voice and/or v, are more relevant to the licensing of the direct object, thus should be investigated for argument licensing (see Béjar and Rezac 2003; Preminger 2014 and references therein).

Note that nothing crucial hinges on the subject being probed first. If the object is probed first, this account would predict the same bleeding effect, but for the subject instead, which is equally problematic for the conditioning of the Set A-B allomorphs.

We are aware, and multiple reviewers have pointed out, that a Multiple Agree approach which places the descriptive burden on the insertion of post-syntactic Vocabulary Items is a viable option. In particular, under this approach the ϕ-features of all arguments would be simultaneously probed in a single Multiple Agree operation and VIs that spellout these features would be underspecified in such a way to describe the distribution. Although, this has the advantage of limiting the typology of probes, this benefit is outweighed by the post-syntactic stipulations necessary to make it work. Specifically, this type of approach is not appealing to us since it (i) requires inherent rankings between VIs based on the Person Hierarchy (which we argue against in 4.1), (ii) still misses generalizations in the data itself (e.g., historically motivated ‘m-class’ suffixes, see Goddard 2007), and (iii) appears to be able to re-describe any given data set without revealing any deeper principles about the grammar (i.e., this type of theory would necessarily have to be constrained in some principled way). Ultimately, we leave this alternative account for future investigation.

Note that under the Contiguous Agree approach to Multiple Agree proposed by Nevins (2011), the ϕ-feature content of arguments does impact the probing of arguments. We do not adopt this aspect of his proposal.

Note that reflexives and passives do not have the theme signs that we typically see in actives. Instead, there are special passive and reflexive suffixes (e.g., -ȧhtse for reflexives) that appear in the same slot and do not change based on the ϕ-feature content of the arguments.

One exception is Arapaho which is unique amongst Algonquian languages in not having an inner suffix, but having separate subject and object markers (Macaulay 2009).

Note that in the Listuguj-dialect, possessive prefixes are uniformly 2nd person for 1st person inclusive possessors (McClay 2012).

Note that in transitive forms with an animate subject and inanimate object (TI), there is some discussion of a different theme sign appearing, but it is not entirely clear if this is a separate morpheme or part of the TI verb final.

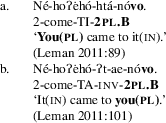

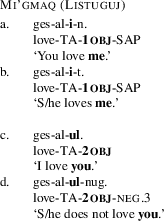

The object making proposal is supported by 3>SAP forms in Mi’gmaq and in embedded clause (or conjunct) forms in other Algonquian languages, 1st and 2nd person markers appear. In the Mi’gmaq examples in (i), the same theme sign indexes a 1st person object (-i) and 2nd person object (-ul) regardless of whether the subject is SAP (ia) and (ic), or 3rd person (ib) and (id), respectively. Note that the negated form is used in (id) since the theme sign and inner suffix are fused in the affirmative form.

-

(i)

-

(i)

Note that -ae is realized as -a word-finally, as in (45c) and (46c).

It appears that the object marking characterization breaks down somewhat with obviatives, since whenever the object is 3rd person obviative only one theme sign appears (-ó). However, when the subject is SAP, an additional suffix (-am) appears before the direct suffix. This differentiates these forms from those with a 3rd person subject. Although it is unclear whether the resulting -amo can be considered as a separate theme sign, -am is characterized by Goddard (2000) as being “thematic.” This provides general support for the claim that the π-features of both the subject and direct object (in transitives) are important to derive the distribution of theme signs in Cheyenne.

Note that #-features do not factor into the distribution of theme signs in Cheyenne, although they do in some languages, such as Mi’gmaq, where there is a separate theme sign to mark 3>SAPpl (-ugsi).

We can imagine a modified Cyclic Agree account in which the π-probe on Voice has no preference, but is simply valued by the most local argument (e.g., the direct object in transitives and the indirect object in ditransitives), which is searched first. Then a second cycle always occurs, in which the next local argument (i.e., the subject) is searched and its π-features condition the allomorph.

References

Anderson, Stephen R. 1992. A-morphous morphology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Baker, Mark C. 2008. The syntax of agreement and concord. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Béjar, Susana, and Milan Rezac. 2003. Person licensing and the derivation of PCC effects. In Romance linguistics: Theory and acquisition, eds. Ana Teresa Pérez-Leroux and Yves Roberge, 49–62. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Béjar, Susana, and Milan Rezac. 2009. Cyclic agree. Linguistic Inquiry 40 (1): 35–73.

Bloomfield, Leonard. 1962. The Menomini language. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Bobaljik, Jonathan David. 2017. Distributed morphology. In Oxford research encyclopedia. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bonet, Eulalia. 1994. The Person-Case Constraint: A morphological approach. MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 22: 33–52.

Brittain, Julie. 1999. A reanalysis of transitive animate theme signs as object agreement: Evidence from Western Naskapi. In Papers of the 30th Algonquian Conference, ed. David H. Pentland, 34–46.

Bruening, Benjamin. 2001. Syntax at the edge: Cross-clausal phenomena and the syntax of Passamaquoddy. PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Chomsky, Noam. 2000. Minimalist inquiries: The framework. In Step by step: Essays on minimalist syntax in honor of Howard Lasnik, eds. Roger Martin, David Michaels, and Juan Uriagereka, 89–115. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2001. In Derivation by phase. Ken Hale: A life in language, ed. by Michael Kenstowicz, 1–52, Cambridge: MIT Press.

Coon, Jessica, and Alan Bale. 2014. The interaction of person and number in Mi’gmaq. NordLyd 41 (1): 85–101.

Coppock, Elizabeth, and Stephen Wechsler. 2012. The objective conjugation in Hungarian: Agreement without phi-features. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 30 (3): 699–740.

Deal, Amy Rose. 2015. Interaction and satisfaction in φ-agreement. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 45, eds. Thuy Bui and Deniz Özyildiz.

Despić, Miloje, and Sarah Murray. 2018. On binary features and disagreeing natural classes: Evidence from Cheyenne and Serbian. The Linguistic Review 35 (2).

Ellis, C. Douglas. 1983. Spoken Cree: West coast of James Bay, revised edn. Edmonton: Pica Pica Press.

Fidelholtz, James Lawrence. 1968. Micmac morphophonemics. PhD diss., MIT.

Fisher, Louise, Wayne Leman, Leroy Pine Sr., and Marie Sanchez. 2006. Cheyenne dictionary. Lame Deer: Chief Dull Knife College.

Goddard, Ives. 1967. The Algonquian independent indicative. National Museum of Canada Bulletin 214: 66–106.

Goddard, Ives. 2000. The historical origins of Cheyenne inflections. In 31st Algonquian Conference, ed. John Nichols, 77–129. Albany: SUNY Press.

Goddard, Ives. 2007. Reconstruction and history of the independent indicative. In 38th Algonquian Conference, ed. H. C. Wolfart, 207–271. Albany: SUNY Press.

Halle, Morris. 1997. Distributed morphology: Impoverishment and fission. In Papers at the interface, eds. Benjamin Bruenung, Yoonjung Kang, and Martha McGinnis. Vol. 30 of MITWPL, 425–449. Cambridge: MIT.

Halle, Morris, and Alec Marantz. 1993. Distributed morphology and the pieces of inflection. In The view from building 20, eds. Ken Hale and Samuel Keyser, 111–176. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Hamilton, Michael David. 2015a. The syntax of Mi’gmaq: A configurational account. PhD diss., McGill University.

Hamilton, Michael David. 2015b. Default agreement in Mi’gmaq possessor raising and ditransitive constructions. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 45, eds., Thuy Bui, and Deniz Özyildiz.

Harley, Heidi, and Elizabeth Ritter. 2002. Person and number in pronouns: A feature-geometric analysis. Language 78 (3): 482–526.

Hiraiwa, Ken. 2001. Multiple agree and the defective intervention constraint in Japanese. MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 40: 67–80.

Hiraiwa, Ken. 2005. Dimensions of symmetry in syntax: Agreement and clausal architecture. PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Hornstein, Norbert. 1999. Movement and control. Linguistic Inquiry 30 (1): 69–96.

Kayne, Richard. 2002. Pronouns and their antecedents. In Derivation and explanation in the minimalist program, eds. Samuel D. Epstein and T. Daniel Seely, 133–166. Malden: Blackwell.

Kiparsky, Paul. 1972. Explanation in phonology. In Goals of linguistic theory, ed. Stanley Peters, 454–468. Upper Saddle River: Prentice-Hall.

Leman, Wayne. 2011. A reference grammar of the Cheyenne language, 4nd edn., Raleigh: Lulu Press. Update of 1980 version, Occasional Publications in Anthropology, Linguistics Series, No. 5. Museum of Anthropology, University of Northern Colorado.

Lochbihler, Bethany. 2012. Aspects of argument licensing. PhD diss., McGill University.

Lochbihler, Bethany, and Eric Mathieu. 2016. Clause typing and feature inheritance of discourse features. Syntax 19 (4): 354–391.

Macaulay, Monica. 2009. On prominence hierarchies: Evidence from Algonquian. Linguistic Typology 13 (3): 357–389.

MacKenzie, Marguerite Ellen. 1980. Towards a dialectology of Cree-Montagnais-Naskapi. PhD diss., University of Toronto.

McClay, Elise. 2012. Possession in Mi’gmaq. Honors thesis, McGill University.

McGinnis, Martha. 1999. Is there syntactic inversion in Ojibwa. In Papers from the Workshop on Structure and Constituency in Languages of the Americas (WSCLA), eds. Leora Bar-el, Rose-Marie DéChaine, and Charlotte Reinholtz. Mit occasional papers in linguistics 17, 101–118.

Nevins, Andrew. 2007. The representation of third person and its consequences for person-case effects. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 25 (2): 273–313.

Nevins, Andrew. 2011. Multiple agree with clitics: Person complementarity vs. omnivorous number. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 29 (4): 939–971.

Oxford, William Robert. 2014. Microparameters of agreement: A diachronic perspective on Algonquian verb inflection. PhD diss., University of Toronto.

Preminger, Omer. 2014. Agreement and its failures. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Reuland, Eric, and Stefan Müller. 2005. Binding conditions: How are they derived? In 12th Conference on Head-Driven Phrase Structure Grammar (HPSG), 578–593. Stanford: CSLI.

Reuland, Eric J. 2011. Anaphora and language design. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Rhodes, Richard. 1994. Agency, inversion, and thematic alignment in Ojibwe. In Berkeley Linguistics Society (BLS) 20, 431–446.

Valentine, Randy. 2001. Nishnaabemwin reference grammar. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Zeijlstra, Hedde. 2004. Sentential negation and negative concord. Utrecht: LOT.

Zwart, Jan-Wouter. 2002. Issues relating to a derivational theory of binding. In Derivation and explanation in the minimalist program, eds. Samuel David Epstein and T. Daniel Seely, 269–304. Malden: Blackwell.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the participants of the 39th Generative Linguistics in the Old World, the 34th West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics, the 22nd Workshop on the Structure and Constituency of the Languages of the Americas, students in our 2016 Cornell syntax seminar, John Bowers, Will Oxford, and the editors and anonymous reviewers.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Despić, M., Hamilton, M.D. & Murray, S.E. A Cyclic and Multiple Agree account. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 37, 51–89 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-018-9405-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-018-9405-4

raised high pitch vowel, V́ high pitch vowel,

raised high pitch vowel, V́ high pitch vowel,  mid pitch vowel, and V low pitch vowel. All final vowels are voiceless (not marked, by convention), but their underlying pitch can affect the pitch of other vowels (see Leman

mid pitch vowel, and V low pitch vowel. All final vowels are voiceless (not marked, by convention), but their underlying pitch can affect the pitch of other vowels (see Leman  / 1-give-

/ 1-give- ‘We(

‘We( ) gave her/him/them(

) gave her/him/them(