Abstract

We provide an analysis of focus and exhaustive focus in the Grassfields Bantu language Awing. We show that Awing provides an exceptionally clear window into the syntactic properties of exhaustive focus. Our analysis reveals that the Awing particle lə́ (le) realizes a left-peripheral head which, in terms of its syntactic position in the functional sequence, closely corresponds to the Foc(us) head in standard cartographic analyses (e.g., Rizzi 1997). Crucially, however, we show that le is only used if the focus it associates with receives a presuppositional exhaustive (cleft-like) interpretation. Other types of focus are not formally encoded in Awing. In order to reflect this semantic specification of le, we call its syntactic category Exh rather than Foc. Another point of difference from what one would consider a “standard” cartographic Foc head is that the focus associated with le is not realized in its specifier but rather within its complement. More particularly, we argue that le associates with the closest maximal projection it asymmetrically c-commands. The broader theoretical relevance of the present work is at least two-fold. First, our paper offers novel evidence in support of Horvath’s (2010) Strong Modularity Hypothesis for Discourse Features, according to which information structural notions such as focus cannot be represented in narrow syntax as formal features. We argue that the information structure-related movement operations that Awing exhibits can be accounted for by interface considerations, in the spirit of Reinhart (2006). Second, our data support the generality of the so-called closeness requirement on association with focus (Jacobs 1983), which dictates that a focus-sensitive particle be as close to its focus as possible (in terms of c-command). What is of special significance is the fact that Awing exhibits two different avenues to satisfying closeness. The standard one—previously described for German or Vietnamese and witnessed here for the Awing particle tśɔ’ə ‘only’—relies primarily on the flexible attachment of the focus-sensitive particle. The Awing particle le, in contrast, is syntactically rigid. For that reason, the satisfaction of closeness relies solely on the flexibility of other syntactic constituents.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

All Awing data and the corresponding judgments are accredited to Henry Fominyam and Melvis Ngwemeshi (both native speakers of Awing). The following abbreviations are used in the glosses throughout the paper: 1/2/3 = 1st/2nd/3rd person; acc = accusative; comp = complementizer; f1 = future tense 1 (later today); f2 = future tense 2 (tomorrow or later); hab = habitual; impf = imperfective; inf = infinitive; neg = negation (plain negation); neg1 = negation 1 (discontinuous negation); neg2 = negation 2 (discontinuous negation); p1 = past tense 1 (earlier today); p2 = past tense 2 (yesterday or earlier); pl plural; perf = perfective; prog = progressive; rel.comp = relative complementizer; res.pron = resumptive pronoun; sg = singular; sm = subject marker.

A useful overview of the so-called “focus movement,” with special reference to Hungarian, can be found in Szendrői (2005).

Rizzi (1997) and many others who follow him place Foc above Fin, which in turn is placed above T. It is not that unlikely, however, that Rizzi’s Fin is a species of T, which would bring the classical analysis closer to the present one.

As we mentioned above, Horvath (2007) suggests that “focus fronted” constituents in Hungarian need not be focused at all. As far as we can tell, this is only partly true: the pertinent data seem to point in the direction of the so-called “second occurrence focus”; see Baumann (2014) for a recent overview.

See ethnologue.com/17/language/azo/ for more. Accessed 9 March 2017.

See glottolog.org/resource/languoid/id/awin1248 for more. Accessed 9 March 2017.

The only exception to this generalization is constituted by sentences with discontinuous negation, which, we believe, involves a morpheme that can either be a prefix or be free. Examples are provided below.

Structures with discontinuous negation could be taken to reveal that Awing is, at some level of representation, an OV language. Its OV nature would typically be obscured by V-movement to higher functional heads; in Sect. 4.2 we show that such a movement is indeed motivated for Awing. The free morpheme variant of the negative morpheme kě would then represent a head to which V cannot adjoin. This kind of approach to V-positioning has been proposed by Koopman (1984) for Vata and more recently Kandybowicz (2008) for Nupe.

An anonymous reviewer kindly points out that a similar VO–OV alternation under negation was observed for Niger-Congo spoken in the Macro-Sudan belt, where OV may be a reflex of Proto Niger Congo (see e.g., Givón 1975).

The prefix phonetically fuses with the initial consonant of its host if the latter is also nasal. Since this leaves no phonetic trace (such as lengthening), we do not include it in the examples.

The function of the n- prefix remains largely obscure. As pointed out by Tamanji (2009) for the closely related language Bafut, n- is probably related to a nominalizing prefix with the same phonological properties. This might suggest that the bare forms and the n- prefixed forms are two variants of verbal stems/non-finite forms, selected in different contexts (similarly to the English distinction between bare infinitives and to infinitives, cf. I must go vs. I have to go.).

We do not analyze interrogative wh-words in this paper, but it is notable that they behave on a par with foci. By default, they are realized in situ and remain morphosyntactically unmarked. They can, just like foci, be associated with the le particle, giving rise to cleft-like questions (‘Who is it that…’) with the expected meaning. Some examples of wh-questions will be given shortly. See Fominyam (2015) for a more detailed discussion.

An anonymous reviewer is wondering how Awing expresses other types of foci, such as verum (polarity) focus or focus on elements expressed by prefixes in Awing, such as tense or aspect. A detailed analysis of these goes beyond the scope of this paper, but in a nutshell, we can say the following: There is no dedicated construction for verum focus. Standard structures are used and verum focus interpretation is a result of discourse pragmatics. Answerhood focus on prefixes receives no special encoding, in line with what is said in Sect. 3.1. Concerning bound (associated) focus, there is no way prefixes can be associated with ‘only’ or le (association with ‘also’ is pragmatic and hence available). This follows from our proposal that association is only possible with maximal projections (see Sect. 4.3). The intended interpretation must be expressed by a paraphrase whereby the semantics of the prefix is expressed, in one way or another, by a full phrase.

Short answers (utterances consisting of the focused expression alone) are the most preferred way of answering wh-questions in Awing. We follow the common practice in using the relatively marked sentential utterances, in order to be able to inspect the formal properties of focus.

The reader should not get confused by the XF or [X]F notation used in our examples: it is intended to indicate semantic focus only, not its formal encoding. Moreover, we distinguish between the ordinary subscript F (indicating the focused constituent) and the boldface subscript F, indicating formal F-marking. The concept of F-marking will be introduced in Sect. 4.3.

This should be read as a descriptive statement. At present, we cannot rule out the possibility that tśɔ’ə ‘only’ adjoins to some (maximal) verbal projection, as argued for German nur ‘only’ by Büring and Hartmann (2001).

The reader will have noticed that object focus (illustrated in (30a)) and VP focus (illustrated in (31c)) are formally indistinguishable from one another. It is discourse pragmatics alone that decides between the two.

These facts show that Awing belongs to the class of languages that express (exhaustive) subject focus by subject–verb inversion and potentially by subject–object inversion. Within the typology of Marten and van der Wal (2014), Awing inversion falls quite neatly into the category of “default agreement inversion” (DAI), with two provisos: first, Awing VS structures do not exhibit “default agreement” but rather exhibit no agreement whatsoever (admittedly, the lack of agreement could be viewed as a special case of default agreement); second, Awing inversion is obligatorily accompanied by le. A more detailed discussion of focus-related subject–verb inversion in Bantu languages would be too much of a distraction, so we limit ourselves to providing a number of relevant references (kindly provided by an anonymous reviewer; for more references, see Marten and van der Wal 2014): Watters 1979 (Aghem), Bresnan and Kanerva 1989 (Chicheŵa), Ndayiragije 1999 (Kirundi), Morimoto 2000 (more Bantu languages), Buell 2006 (Zulu), Zerbian 2006 (Northern Sotho), Zeller 2008 (Zulu), Carstens and Mletshe 2015 (Xhosa).

Agreement asymmetries of this kind are quite common cross-linguistically. They have been extensively discussed for Arabic (see e.g., Harbert and Bahloul 2002) but are also quite common in Bantu languages (e.g., Marten and van der Wal 2014). See also Chomsky (2015) for a recent theoretical discussion.

In more technical terms, the verb head-moves and either left-adjoins or right-adjoins to the higher heads, depending on their morphological specification. We adopt this key ingredient of our analysis in the light of the empirical evidence presented here, as well as in Wiland (2009) or Pesetsky (2013), despite the theoretical reasons that speak either against head-adjunction in general (Matushansky 2006) or, more specifically, head adjunction to the right (Kayne 1994; see also Buell 2005 for a Kaynian analysis of the Zulu verbal complex).

An anonymous reviewer points out that this could be modeled within the account of Matushansky (2006) by stipulating that the verbal complex, after having moved to SpecExhP, is unable to undergo m-merger with Exh, which in turn leaves it free to move further up to SpecAgrP (and undergo m-merger with Agr). See also Bayırlı (2017), who argues that focus-sensitive heads (of which Exh is an example) are never realized as affixes.

Crucially, such an EPP feature must be absent from T (otherwise, Generalization 1 would not be derived). We do not know why this is the case, though it would follow from the plausible assumption that a subject-related EPP is a property that is associated with at most a single head in the extended verbal projection (in a given language).

All these assumptions are expressible as lexical statements, using standard minimalist tenets; e.g., A2 corresponds to the lexical postulate that v, Asp, Neg, and T all have a “strong” [V] feature that must be “checked” (by head-moving V to them). We consider the precise technical formulations immaterial for the present purposes.

An anonymous reviewer is wondering how exactly the (non-)projection of Agr is regulated. Our approach implies that Agr can but need not be projected. At the same time, however, the non-projection of Agr is heavily constrained: it is only allowed if the subject is exhaustively focused; in all other cases, Agr projects obligatorily. This situation can be characterized in terms of a violable (interface) constraint that dictates that Agr be projected (in finite clauses). The only situation where the constraint is licitly violated is one where the subject is exhaustively focused, whereby the non-projection (and hence in situ subject) is the only way of achieving the intended interpretation. In optimality-theoretic terms, the requirement to express exhaustive focus grammatically dominates the requirement to project Agr.

That is to say, tśɔ’ə ‘only’ in Awing induces F-marking within its complement (anticipating the proposal). This would hold both if ‘only’ attached directly to the focused constituent or, in line with Büring and Hartmann (2001), to some extended projection of VP. An anonymous reviewer asks how kə́- ‘also’ associates with focus in Awing. Based on the data from Sect. 3, we assume that kə́- operates on a set of alternatives (possibly a question under discussion) that are determined purely contextually. Hence, no F-marking is needed for kə́- (or for answerhood focus). We are aware that the absence of F-marking in structures without (certain) particles implies the non-existence of semantic focus alternatives (and hence, no way of checking for question–answer congruence). While this might be conceptually unsettling, it is what the empirical situation suggests.

We are grateful to Jakub Dotlačil for making us aware of this problem.

Mitcho Erlewine (p.c.) rightly points out that traces must be excluded from F-marking by Exh, in order for the account to work as intended. For relevant discussion on the F-marking of traces, see Erlewine (2014).

An anonymous reviewer suggests that F-marking by Exh could be simplified by assuming that Exh F-marks everything (or possibly anything) in its (asymmetric) c-command domain. In some cases, this would necessitate rightward movement above ExhP. See fn. 42 for more discussion.

The same anonymous reviewer wonders whether one could avoid structure-based F-marking altogether, by stipulating covert movement of the focused constituent to SpecExhP. Awing would then be, in a way, a covert version of Hungarian. While we do not have direct arguments against this hypothesis, we see two conceptual issues with it. Firstly, we are not convinced that structure-based F-marking is avoided under this account. One would still have to stipulate (as one must for Hungarian, with the potential proviso of exhaustive non-foci; but see fn. 8) that F-marking targets either the constituent in SpecExhP or a constituent dominated by it; i.e., it would be structurally constrained. Secondly, the choice of the target of the covert movement would be constrained by minimality: only the constituent closest to Exh could be attracted to SpecExhP. Thus, the very same relation that we now use for F-marking would still be required, namely for attraction purposes. As a result, such an analysis would achieve the same effect as ours, just with more syntactic instruments (movement would have to be added). In the absence of direct evidence for it, we see no reason to adopt it. The question that remains is how exactly Awing differs from Hungarian if not in the “strength” of a formal feature (or: overt vs. covert movement/Agree). We believe that the difference can be modeled in semantics (semantic lexical specification of the Exh head): Hungarian Exh requires two arguments (being focus-sensitive upon the second one), while Awing Exh only requires one argument. This difference bears a relation to the familiar distinction between structured propositions and alternative semantics. A full exposition of the idea would take up another paper, so we have to leave it at this.

An anonymous reviewer points out that the assignment of referential indices is not structurally constrained (which leaves an important aspect of structural F-marking unaccounted for). We agree that in general, this is indeed generally the case. Depending on one’s analysis of reflexive anaphora, however, it could be that the assignment of a referential index to a reflexive anaphor is structurally constrained (obligatory co-indexing with the closest subject).

Interestingly, there seem to be no pronouns for verbal heads, which is arguably related to the fact that V (in T) does not intervene for focus association from Exh. This is expressed by the more general statement that le can only associate with maximal projections. For a related issue, see Büring and Hartmann (2001), who observe that focus-sensitive particles cannot adjoin to non-maximal projections.

An anonymous reviewer suggests that our analysis is related to those which assume that the verb phrase is, in one way or another, the “focus domain” of the Bantu clause (see e.g., Buell 2009; Cheng and Downing 2009; Zeller 2015) and that our “out of focus” movements could be analyzed as movements out of such a domain. We do not exclude the possibility that there is a deeper relation with previous proposals (see esp. our concluding discussion in Sect. 5), but one should not jump to conclusions based on superficial similarities. First of all, the “focus domain” in Awing is the whole complement of Exh, presumably larger than the usually assumed “verb phrase”. Secondly, the “focus domain” only concerns exhaustive focus in Awing. Other foci can appear anywhere else. Last but not least, there are important details to pay attention to. Cheng and Downing (2009), for instance, argue that the verb phrase is a domain for prosodic prominence assignment, and only secondarily a “focus domain”. Zeller (2015) argues that the evacuation “out of focus” movement is driven by an [antifocus] feature, something that we consider unsubstantiated for the Awing case.

A careful reader might notice that this would compromise our basic assumption that exhaustive focus is the closest constituent asymmetrically c-commanded by le. In particular, if (temporal) adjuncts were structurally higher than objects, they would always block exhaustive focusing of objects. For instance, the example (57a) would be a case of adjunct focus, rather than object focus, contrary to facts. Gisbert Fanselow (p.c.) notes that this problem would be avoided if Generalization 1 and the associated rule of F-marking by Exh were formulated in terms of linear order rather than c-command. We agree with an anonymous reviewer that this would imply a substantial modification to the assumptions introduced in Sect. 4.3. In particular, linear association would necessitate a direct communication between compositional semantics and PF. The empirical problem we see with a linear account is that it would leave us with no systematic take on focus ambiguities.

Our working assumption is that the non-canonical order is derived by a scrambling of the focused constituent across the backgrounded ones. While scrambling of foci is ungrammatical in some languages, such as German (Lenerz 1977), others seem to allow for it, such as Japanese or some Slavic languages (Bošković 2009). An anonymous reviewer points out that the non-canonical orders could also be derived by rightward-moving the backgrounded constituents. Such an analysis would, however, lead to a configuration where the backgrounded constituents asymmetrically c-command the focused one, which would in turn predict wrong associative behavior of le (two provisos: (i) rightward movement could target a position above ExhP; (ii) association could be linear rather than structural; see fn. 41).

This state of affairs contrasts with the facts discussed in Sect. 3, where we saw that the default word order imposes no information structural restrictions.

An anonymous reviewer correctly points out that the proposed subject focus configurations allow for an interpretation whereby the focus is on the whole xVP, as that constituent is also asymmetrically c-commanded by le. This would, in effect, amount to placing exhaustive focus on the whole clause. According to the intuition of Henry Fominyam, however, such an interpretation is not available in the pertinent construction. The reason for the missing interpretation could be that it is pragmatically highly marked to have exhaustive focus with no background and therefore, a very unrestricted set of alternatives. It is interesting to note, however, that there are languages that exhibit the predicted behavior (to the extent that our predictions extend to them). Somali, for instance, uses the particle baa to mark focus on the element that precedes it (see Hyman and Watters 1984:241–242). If baa follows the object in Somali, an object or a VP focus interpretation is available (a situation comparable to the Awing one). If baa follows the subject, however, a subject or a clause focus interpretation is available.

Recall that verb doubling also occurs in cases of verb focus. We turn to those cases shortly.

The tendency to interpret the pre-le constituent as contrastive topic could well be due to the general tendency to place contrastive topics before foci which in turn might be related to the tendency to place discourse given material in front of discourse new material. For some general discussion, see Fanselow (2008).

Notice that, strictly speaking, le cannot associate with V itself because it is not a maximal projection. Therefore, the association is, by hypothesis, with the smallest VP containing the V.

An anonymous reviewer kindly points out that the present analysis receives indirect cross-linguistic support from languages in which verb focus is expressed by the disjoint verb form, which in turn implies that everything (but the verb) has evacuated from the VP. Zulu is a case in point; see Buell (2006).

This situation is reminiscent (and arguably somehow related) to the well-known phenomenon of focus projection in languages like English, where prosodic prominence on the suitable element (marked by capitals) leaves the information structure of a sentence underspecified.

-

(i)

-

(i)

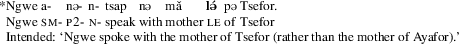

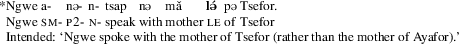

Note that placing le on the possessor pə Tsefor ‘of Tsefor’ is ungrammatical, as shown in example (i). This follows under our present proposal if the movement of the possessee (nə) mǎ ‘(with) mother’ cannot strand this possessor. Such restrictions are, of course, not uncommon crosslinguistically.

-

(i)

-

(i)

A competing proposal for English clefts has recently been developed by Büring and Križ (2013) and Križ (to appear). We rely on Velleman et al.’s analysis more or less for expository purposes. At present, we cannot exclude the possibility that Büring and Križ (2013) or Križ (to appear) provide a more adequate account of the semantics of Awing le constructions.

See Velleman et al. (2012) for an analysis of ‘only’ that uses the same ingredients as their analysis of clefts.

The reader should not get confused by the presence of lə́ in (73). This is not the le particle but the conjunction ‘but.’ We leave open the obvious question whether this homonymy is accidental or not.

References

Aboh, Enoch. 1998. From the syntax of Gungbe to the grammar of Gbe. PhD diss., University of Geneva.

Aboh, Enoch. 2004. The morphosyntax of complement-head sequences: Clause structure and word order patterns in Kwa. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Aboh, Enoch. 2006. When verbal predicates go fronting. In ZAS papers in linguistics 46: Papers on information structure in African languages, eds. Ines Fiedler and Anne Schwarz, 21–48. Berlin: Zentrum für Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft.

Aboh, Enoch, and Marina Dyakonova. 2009. Predicate doubling and parallel chains. Lingua 119 (7): 1035–1065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2008.11.004.

Azieshi, Gisele. 1994. Phonologie structurale de l’Awing. PhD diss., Université de Yaoundé.

Baumann, Stefan. 2014. Second occurrence focus. In The Oxford handbook of information structure, eds. Caroline Féry and Shinichiro Ishihara. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199642670.013.38.

Bayırlı, İsa Kerem. 2017. On an impossible affix. In MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 81: Papers in morphology, eds. Snejana Iovtcheva and Benjamin Storme, 1–14. Cambridge: MITWPL.

Beaver, David, and Brady Clark. 2008. Sense and sensitivity: How focus determines meaning. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444304176.

Belletti, Adriana. 2004. Aspects of the low IP area. In The structure of CP and IP: The cartography of syntactic structures, Vol. 2, ed. Luigi Rizzi, 16–51. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Biloa, Edmond. 2015. Cartography and antisymmetry: Essays on the nature and structure of the C and I domains. Ms., University of Yaoundé I.

Bošković, Željko. 2009. Scrambling. In Die Slavischen Sprachen/The Slavic languages. Halbband 1: Handbücher zur Sprach- und Kommunikationswissenschaft, eds. Sebastian Kempgen, Peter Kosta, Tilman Berger, and Karl Gutschmidt, 714–725. Berlin: De Gruyter.

Bresnan, Joan, and Jonni Kanerva. 1989. Locative inversion in Chicheŵa: A case study of factorization in grammar. Linguistic Inquiry 20 (1): 1–50.

Brody, Michael. 1995. Focus and checking theory. In Approaches to Hungarian 5: Levels and structures, ed. István Kenesei, 31–43. Szeged: JATEPress.

Buell, Leston C. 2005. Issues in Zulu verbal morphosyntax. PhD diss., University of California at Los Angeles.

Buell, Leston C. 2006. The Zulu conjoint/disjoint verb alternation: Focus or constituency? In ZAS papers in linguistics 43: Papers in Bantu grammar and description, eds. Laura Downing, Lutz Marten, and Sabine Zerbian, 9–30. Berlin: Zentrum für Allgemeine Sprachwissenschaft.

Buell, Leston C. 2009. Evaluating the immediate postverbal position as a focus position in Zulu. In 38th Annual Conference on African Linguistics (ACAL), eds. Masangu Matondo, Fiona McLaughlin, and Eric Potsdam, 166–172. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project. Available at http://www.lingref.com/cpp/acal/38/paper2144.pdf. Accessed 9 March 2017.

Büring, Daniel. 2003. On D-trees, beans, and B-accents. Linguistics and Philosophy 26 (5): 511–545.

Büring, Daniel. 2010. Towards a typology of focus realization. In Information structure: Theoretical, typological, and experimental perspectives, eds. Malte Zimmermann and Caroline Féry, 177–205. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Büring, Daniel, and Katharina Hartmann. 2001. The syntax and semantics of focus-sensitive particles in German. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 19 (2): 229–281. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010653115493.

Büring, Daniel, and Manuel Križ. 2013. It’s that, and that’s it! Exhaustivity and homogeneity presuppositions in clefts (and definites). Semantics and Pragmatics 6 (6): 1–29. https://doi.org/10.3765/sp.6.6.

Carstens, Vicki, and Loyiso Mletshe. 2015. Radical defectivity: Implications of Xhosa expletive constructions. Linguistic Inquiry 46 (2): 187–242. Available at https://muse.jhu.edu/article/579454. Accessed 9 March 2017.

Cheng, Lisa Lai-Shen, and Laura Downing. 2009. Where’s the topic in Zulu? The Linguistic Review 26 (2-3): 207–238. https://doi.org/10.1515/tlir.2009.008.

Cheng, Lisa Lai-Shen, and Laura Downing. 2013. Clefts in Durban Zulu. In Cleft structures, eds. Katharina Hartmann and Tonjes Veenstra, 141–164. Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/la.208.05che.

Chomsky, Noam. 2001. Derivation by phase. In Ken Hale: A life in language, ed. Michael Kenstowicz, 1–52. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 2015. Problems of projection: Extensions. In Structures, strategies, and beyond: Studies in honour of Adriana Belletti, eds. Elisa Di Domenico, Cornelia Hamann, and Simona Matteini, 1–16. Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/la.223.01cho.

Collins, Chris, and Komlan E. Essizewa. 2007. The syntax of verb focus in Kabiye. In 37th Annual Conference on African Linguistics (ACAL), eds. Doris L. Payne and Jaime Peña, 191–203. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project. Available at http://www.lingref.com/cpp/acal/37/paper1606.pdf. Accessed 9 March 2017.

Devos, Maud, and Johan van der Auwera. 2013. Jespersen cycles in Bantu: Double and triple negation. Journal of African Languages and Linguistics 34 (2): 205–274. https://doi.org/10.1515/jall-2013-0008.

Erlewine, Michael Yoshitaka. 2014. Movement out of focus. Cambridge: MIT.

Erlewine, Michael Yoshitaka. To appear. Vietnamese focus particles and derivation by phase. Journal of East Asian Linguistics.

Erlewine, Michael Yoshitaka, and Hadas Kotek. 2016. Tanglewood untangled. In 26th conference on Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT), 224–243. Available at http://journals.linguisticsociety.org/proceedings/index.php/SALT/article/download/26.224/3642.pdf. Accessed 9 March 2017.

Fanselow, Gisbert. 2006. On pure syntax (uncontaminated by information structure). In Form, structure, and grammar, eds. Patrick Brandt and Eric Fuß, 137–157. Berlin: Akademie. https://doi.org/10.1524/9783050085555.137.

Fanselow, Gisbert. 2008. In need of mediation: The relation between syntax and information structure. Acta Linguistica Hungarica 55 (3-4): 397–413. https://doi.org/10.1556/ALing.55.2008.3-4.12.

Fanselow, Gisbert, and Denisa Lenertová. 2011. Left peripheral focus: Mismatches between syntax and information structure. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 29 (1): 169–209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-010-9109-x.

Fiedler, Ines, Katharina Hartmann, Brigitte Reineke, Anne Schwarz, and Malte Zimmermann. 2010. Subject focus in West African languages. In Information structure: Theoretical, typological, and experimental perspectives, eds. Malte Zimmermann and Caroline Féry, 234–257. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fominyam, Henry. 2012. Towards the fine structure of Awing left periphery. Master’s thesis, University of Yaoundé I.

Fominyam, Henry. 2015. The syntax of focus and interrogation in Awing: A descriptive approach. In Interdisciplinary studies on information structure 19: Mood, exhaustivity, and focus marking in non-European languages, eds. Mira Grubic and Felix Bildhauer, 29–62. Potsdam: Universitätsverlag Potsdam. Available at https://publishup.uni-potsdam.de/opus4-ubp/frontdoor/index/index/docId/8120. Accessed 9 March 2017.

Fox, Danny, and David Pesetsky. 2005. Cyclic linearization of syntactic structure. Theoretical Linguistics 31 (1-2): 1–45. https://doi.org/10.1515/thli.2005.31.1-2.1.

Givón, Talmy. 1975. Serial verbs and syntactic change: Niger-Congo. In Word order and word order change, ed. Charles N. Li, 47–112. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Güldemann, Tom. 2003. Present progressive vis-à-vis predication focus in Bantu: A verbal category between semantics and pragmatics. Studies in Languages 27 (2): 323–360. https://doi.org/10.1075/sl.27.2.05gul.

Harbert, Wayne, and Maher Bahloul. 2002. Postverbal subjects in Arabic and the theory of agreement. In Themes in Arabic and Hebrew syntax, eds. Jamal Ouhalla and Ur Shlonsky, 45–70. Dordrecht: Kluwer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-010-0351-3_2.

Horvath, Julia. 1995. Structural focus, structural case, and the notion of feature-assignment. In Discourse configurational languages, ed. Katalin É. Kiss, 28–64. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Horvath, Julia. 2000. Interfaces vs. the computational system in the syntax of focus. In Interface strategies, eds. Hans Bennis, Martin Everaert, and Eric Reuland, 183–206. Amsterdam: Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences.

Horvath, Julia. 2005. Is ‘focus movement’ driven by stress? In Approaches to Hungarian 9, 131–158. Szeged: JATEPress.

Horvath, Julia. 2007. Separating “focus movement” from focus. In Phrasal and clausal architecture: Syntactic derivation and interpretation, eds. Simin Karimi, Vida Samiian, and Wendy K. Wilkins, 108–145. Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/la.101.07hor.

Horvath, Julia. 2010. “Discourse features,” syntactic displacement, and the status of contrast. Lingua 120 (6): 1346–1369. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2008.07.011.

Horvath, Julia. 2013. Focus, exhaustivity, and the syntax of wh-interrogatives: The case of Hungarian. In Approaches to Hungarian 13: Papers from the 2011 Lund conference, eds. Johan Brandtler, Valéria Molnár, and Christer Platzack, 97–132. Amsterdam: Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/atoh.13.06hor.

Hyman, Larry M., and Maria Polinsky. 2010. Focus in Aghem. In Information structure: Theoretical, typological, and empirical perspectives, eds. Malte Zimmermann and Caroline Féry, 206–233. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hyman, Larry M., and John R. Watters. 1984. Auxiliary focus. Studies in African Linguistics 15 (3): 233–273. Available at http://sal.research.pdx.edu/PDF/153Hyman_Watters.pdf. Accessed 9 March 2017.

Jackendoff, Ray. 1972. Semantic interpretation in generative grammar. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Jacobs, Joachim. 1983. Fokus und Skalen: Zur Syntax und Semantik von Gradpartikeln im Deutschen. Tübingen: Niemeyer.

Kandybowicz, Jason. 2008. The grammar of repetition: Nupe grammar at the syntax-phonology interface. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Kayne, Richard S. 1994. The antisymmetry of syntax. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kenesei, István. 1986. On the logic of Hungarian word order. In Topic, focus, and configurationality, eds. Werner Abraham and Sjaak de Meij, 143–159. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Koopman, Hilda. 1984. The syntax of verbs. Dordrecht: Foris.

Kratzer, Angelika. 1991. The representation of focus. In Semantics: An international handbook of contemporary research, eds. Arnim vonStechow and Dieter Wunderlich, 825–834. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Krifka, Manfred. 2007. Basic notions of information structure. In Interdisciplinary studies on information structure 6: The notions of information structure, eds. Caroline Féry, Gisbert Fanselow, and Manfred Krifka, 13–55. Potsdam: Universitätsverlag Potsdam. Available at http://www.sfb632.uni-potsdam.de/images/isis/isis06.pdf. Accessed 9 March 2017.

Križ, Manuel. To appear. It-clefts, exhaustivity, and definite descriptions. In Questions in discourse, eds. Klaus von Heusinger, Edgar Onea, and Malte Zimmermann. Amsterdam: Brill.

Laka, Itziar. 1990. Negation in syntax: On the nature of functional categories and projections. PhD diss., MIT.

Leffel, Timothy, Radek Šimík, and Marta Wierzba. 2014. Pronominal F-markers in Basaá. In 43rd annual meeting of the North East Linguistic Society (NELS), eds. Hsin-Lun Huang, Ethan Poole, and Amanda Rysling, 265–276. Amherst: GLSA.

Lenerz, Jürgen. 1977. Zur Abfolge nominaler Satzglieder im Deutschen. Tübingen: Narr.

Marten, Lutz, and Jenneke van der Wal. 2014. A typology of Bantu subject inversion. Linguistic Variation 14 (2): 318–368. https://doi.org/10.1075/lv.14.2.04mar.

Matushansky, Ora. 2006. Head movement in linguistic theory. Linguistic Inquiry 37 (1): 69–109.

Morimoto, Yukiko. 2000. Discourse configurationality in Bantu morphosyntax. PhD diss., Stanford University.

Ndayiragije, Juvénal. 1999. Checking economy. Linguistic Inquiry 30 (3): 399–444.

Pesetsky, David. 2013. Russian case morphology and the syntactic categories. Cambridge: MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9780262019729.001.0001.

Reinhart, Tanya. 1995. Interface strategies. In OTS working papers in theoretical linguistics 95-002. Utrecht: OTS.

Reinhart, Tanya. 1997. Interface economy: Focus and markedness. In The role of economy principles in linguistic theory, eds. Chris Wilder, Hans-Martin Gärtner, and Manfred Bierwisch, 146–169. Berlin: Akademischer.

Reinhart, Tanya. 2006. Interface strategies: Optimal and costly computations. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Rizzi, Luigi. 1997. The fine structure of the left periphery. In Elements of grammar: A handbook of generative syntax, ed. Liliane Haegeman, 281–337. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Rizzi, Luigi. 2013. Introduction: Core computational principles in natural language syntax. Lingua 130: 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2012.12.001.

Rooth, Mats. 1985. Association with focus. PhD diss., University of Massachusetts at Amherst.

Rooth, Mats. 1992. A theory of focus interpretation. Natural Language Semantics 1 (1): 75–116. Available at https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02342617.

Sabel, Joachim, and Jochen Zeller. 2006. Wh-question formation in Nguni. In 35th Annual Conference on African Linguistics (ACAL), eds. John Mugane, John P. Hutchison, and Dee A. Worman, 271–283. Somerville: Cascadilla Proceedings Project. Available at http://www.lingref.com/cpp/acal/35/paper1316.pdf. Accessed 9 March 2017.

Szendrői, Kriszta. 2005. Focus movement (with special reference to Hungarian). In The Blackwell companion to syntax, eds. Martin Everaert and Henk van Riemsdijk, Vol. 2, 270–335. London: Blackwell.

Tamanji, Pius N. 2009. A descriptive grammar of Bafut. Köln: Rüddiger Köppe.

Travis, Lisa. 1984. Parameters and effects of word order variation. PhD diss., MIT.

Tsimpli, Ianthi-Maria. 1995. Focussing in modern Greek. In Discourse configurational languages, ed. Katalin É. Kiss, 176–206. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tuller, Laurice. 1992. The syntax of postverbal focus constructions in Chadic. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 10 (2): 303–334. Available at https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00133815.

van der Berg, Bianca. 2009. A phonological sketch of Awing. SIL Cameroon. http://www.silcam.org/languages/languagepage.php?languageid=12. Accessed 9 March 2017.

van der Wal, Jenneke. 2011. Focus excluding alternatives: Conjoint/disjoint marking in Makhuwa. Lingua 121 (11): 1734–1750. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2010.10.013.

van der Wal, Jenneke, and Larry M. Hyman, eds. 2017. The conjoint/disjoint alternation in Bantu. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Velleman, Dan, David Beaver, Emilie Destruel, Dylan Bumford, Edgar Onea, and Liz Coppock. 2012. It-clefts are IT (inquiry terminating) constructions. In 22nd conference on Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT), ed. Anca Chereches, 441–460. https://doi.org/10.3765/salt.v22i0.2640bu.

Velleman, Leah, and David Beaver. 2015. Question-based models of information structure. In The Oxford handbook of information structure, eds. Caroline Féry and Shinichiro Ishihara. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199642670.013.29.

Watters, John R. 1979. Focus in Aghem: A study of its formal correlates and typology. In Aghem grammatical structure, ed. Larry M. Hyman, 137–197. Los Angeles: University of Southern California.

Wiland, Bartosz. 2009. Aspects of order preservation in Polish and English. PhD diss., University of Poznań.

Zeller, Jochen. 2008. The subject marker in Bantu as an antifocus marker. In Stellenbosch Papers in Linguistics 38, 221–254. Stellenbosch University: Department of General Linguistics.

Zeller, Jochen. 2015. Argument prominence and agreement: Explaining an unexpected object asymmetry in Zulu. Lingua 156: 17–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2014.11.009.

Zerbian, Sabine. 2006. Inversion structures in Northern Sotho. Southern African Linguistics and Applied Language Studies 24 (3): 361–376. https://doi.org/10.2989/16073610609486425.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the German Academic Exchange Service (DAAD) (H. Fominyam) and the German Research Foundation (DFG), more particularly by the SFB632: Information Structure (both authors), and, in its final stage, also by the project Definiteness in articleless Slavic languages (R. Šimík).

This work was presented, in various stages of development, at three occasions: at the workshop That depends…, an event associated with the PhD defence of Pavel Rudnev (Groningen, April 2015), in the Potsdam Syntax-Semantics Colloquium (June 2015), and in the Syntax Circle at ZAS Berlin (October 2016). We are grateful to the audiences for the inspiring feedback. We would further like to thank to Jakub Dotlačil, Patrick Elliott, Mitcho Erlewine, Gisbert Fanselow, Ines Fiedler, Berit Gehrke, Fatima Hamlaoui, André Meinunger, Maria Polinsky, Pavel Rudnev, Craig Sailor, Luis Vicente, Jenneke van der Wal, Marta Wierzba, Malte Zimmermann, and Jan-Wouter Zwart. We also profited from the detailed and constructive comments of three anonymous reviewers, as well as our editor, Ad Neeleman. All remaining errors are ours.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fominyam, H., Šimík, R. The morphosyntax of exhaustive focus. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 35, 1027–1077 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-017-9363-2

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-017-9363-2