Abstract

In a partial control configuration the denotation of the controller is properly included in the understood subject of the infinitive. This paper proposes a compositional semantics for partial control—the first such proposal that we are aware of. We show that an account of what determines whether a given predicate licenses partial control follows naturally from the analysis without additional syntactic assumptions. At the heart of the proposal lies the idea that partial control predicates are attitude verbs and as such, quantify over a particularly fine-grained type of modal base—so-called centred worlds. Unlike in traditional semantics for attitude reports, however, the lexical entry of these predicates requires that the property expressed by the control complement is applied not to the coordinates of this modal base, but rather to world, time and individual arguments that stand in a systematic relationship to those coordinates. This makes sense of the observation, going back to Landau (2000), that the ability of a control predicate to license partial control is intimately connected to its temporal properties.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Jackendoff and Culicover (2003) advocate a semantic approach to partial control. Problems with their approach are discussed in Landau (2013a). See also Hornstein (2003), who suggests that partial control may not involve a distinct syntax from exhaustive control, but instead arises via a meaning postulate associated with the semantics of the PC class. With neither of these approaches was a complete compositional semantics for PC provided.

These lists are based on the useful characterization of the PC and EC classes in Landau (2000). The most important differences between his lists and ours are (i) our re-classification of claim and pretend as members of the EC class, based on data that will be introduced in Sect. 3.4; (ii) the addition to the PC class of the verbs expect, vote, advise, recommend and a variant of remember that takes a gerundive complement, which we call remember PC; (iii) the addition to the EC class of the verb deserve. Bowers (2008) disputes the notion that control predicates can be divided into a class that permit PC and a class that do not, and indeed intuitions regarding partial control are notoriously delicate, so that this is an area that is ripe for experimental research. See White and Grano (2014) for a recent experimental study of grammaticality judgments about partial control that lends overall support to the characterization of the empirical landscape given in this paper.

We focus on believe for expository purposes, even though it is not a control predicate in English. It is in many other languages though, including Italian, French and German. Furthermore, the discussion will provide us with the tools to analyze expect, since expectations are merely beliefs about what will happen in the future, as Lewis (1979) noticed.

Notice that this argumentation suggests that when believe embeds an overt de se pronoun, as in \(\mathit{Mary}_{i}\) believes that she i is Napoleon, the embedded clause should also be of property type. Chierchia accommodates this by letting attitude verbs that take finite complements be ambiguous between a Hintikka- and a Lewis/Chierchia-style semantics. If the pronoun is interpreted de se, as in the Napoleon case, it is abstracted over at LF, and the latter type of semantics is assigned to the attitude verb. An alternative is to treat de se pronouns in finite clauses as de re expressions, interpreted with respect to the acquaintance relation of identity (Reinhart 1990; Schlenker 2003; Anand 2006; Maier 2009, 2011). We have nothing to add to the discussion of attitude reports with finite complements in this paper.

The careful reader will notice that the definition of extension is too weak for the case of expect, since it fails to rule out the possibility of having expectations about the past rather than the future. We address this problem in the Appendix by defining different types of extension for different control predicates.

A reviewer asks how this argument would play out in a situation semantics, where worlds have situations as parts. Since according to this view worlds are maximal situations it remains true that if <w″, t″, z> is an extension of <w′, t′, y>, then w″ = w′. On the other hand, if attitude predicates are quantifiers over centred situations rather than centred worlds, as proposed by Stephenson (2010b) for imagine and remember, then in principle it should be possible for the definition of extension to be satisfied non-trivially for the situation/world coordinates. We leave it to future work to investigate whether PC predicates give rise to interpretations involving non-trivial part-whole relationships between situations.

An anonymous reviewer as well as consultants with whom I have discussed the examples remarked that combining surprised and shocked with a for-adverbial delimiting a relatively long duration may in general be dispreferred, for reasons independent of the topic of interest here. For these predicates, the contrast illustrated in (55) and (56) can be brought out by controlling for this confound by means of for-adverbials like for five minutes:

Context: A short meeting has been scheduled on a Sunday morning.

-

(i)

For five minutes, John was surprised/shocked to be in a meeting for ten minutes on a Sunday morning.

-

(ii)

*For ten minutes, John was surprised/shocked to be in a meeting for five minutes on a Sunday morning.

-

(i)

The use of eventive predicates to diagnose (non-)simultaneity has a long history (Abusch 2004; Boskovic 1996, 1997; Enç 1991; Martin 1996, 2001; Pesetsky 1992; Wurmbrand 2014). However, if the arguments described in this paper concerning the distribution of eventive predicates in infinitives is correct, then the only simultaneous predicates that are expected to prohibit eventive predicates are the statives and claim. As shown in Sect. 3.4, pretend is a simultaneous predicate but nonetheless licenses eventive infinitives.

Because enjoy is not stative, the argument from eventive predicates does not apply to this verb. We nonetheless assign it the same semantics as the other emotive factives, on the basis of the facts concerning for-adverbials.

A complete semantics for glad is provided in the Appendix.

We illustrate the idea with an achievement predicate, but the point can also be made with an activity predicate such as dance, or an accomplishment predicate such as build a house. Dance must be construed habitually when embedded in its bare form below believe:

-

(i)

John believed Mary to dance (*at that moment).

Activity predicates lack the subinterval property (Taylor 1977; Dowty 1977, 1979). Consequently, the requirement that (i) entails that in each of John’s belief worlds, ‘Mary dances’ holds at every subinterval of John’s subjective ‘now’ is not satisfied.

Likewise, in its bare form, build a house is ungrammatical (or perhaps marginally allows a habitual reading):

-

(ii)

*John believed Mary to build a house.

This too is due to the fact that the embedded predicate lacks the subinterval property.

-

(i)

This semantics sets aside Bennett and Partee’s condition that the original interval be a non-final subinterval of the shifted one.

Comments from a reviewer persuaded us that auxiliary have in the complement of claim and pretend marks past tense rather than perfective aspect. Landau (2000) notes that have in this environment is compatible with punctual time adverbials, unlike perfective have. The contrast between (ii) and (iii) suggests that have is perfective in the scope of manage; this may be responsible for why PC is not ameliorated in this environment.

-

(i)

John has finished his duties (*at 5 pm).

-

(ii)

John claimed/pretended to have finished his duties at 5 pm.

-

(iii)

John managed to have finished his duties (*at 5 pm).

-

(i)

Rodrigues (2007) provides further evidence that partially controlled PRO inherits phi-features from the controller, based on agreement with epicene nouns in Romance.

A reviewer points out that the question of how PRO comes to inherit the controller’s phi-features remains ill-understood on the property view. We have nothing new to offer concerning this question, but merely assume that data like (90) and Rodrigues’ data are convincing evidence that PRO does indeed inherit the controller’s phi-features.

One of the details that is glossed over here is that if seem is an attitude verb, then strictly speaking John should be construed de re. We have abstracted away from this in order to keep the LF reasonably simple. We continue to assume the standard analysis of de re interpretations by appeal to an acquaintance relation holding between the attitude holder and the res; the target truth conditions in this case can be paraphrased as ‘There is some acquaintance relation R between Mary and John such that for each of Mary’s seem-alternatives <w′, t′, y>, the individual to whom y bears R in w′ assembles in the hall in w′ at t′. This paraphrase reveals that while it looks as though we should have vacuous binding in (98b), a complete LF would provide an individual variable for the individual abstractor to bind. We have retained the individual variable in our computations in order to facilitate comparison between the representations for raising and control. Note that with a raising sentence that does not embed a de se or a de re expression, such as It seems to be raining, a variant of seem that embeds a propositional, rather than property-type complement should be assumed. Vacuous binding is thus avoided in such cases.

The use of doubly centred worlds for communication verbs provides a means of accounting for the observation that with object control with such verbs, PRO is interpreted ‘de te’, meaning that the subject must think of the object as the addressee of her speech act (Schlenker 1999). For further applications of this idea see Uegaki (2011), which uses it as the basis for a solution to the puzzle of controller shift.

This point was also raised by Yasutada Sudo (p.c.).

An anonymous reviewer drew our attention to the following interesting example:

-

(i)

The students each wanted to visit one another.

(We have used one another rather than each other since our informants tell us that the variant of (i) with each other is degraded due to an impression of redundancy created by repetition of each.) The semantics of matrix each requires the predicate wanted to visit one another to be distributed over atomic members of the set of students, while embedded one another is required by the syntax to have a subject that bears the feature [plural]. Our account predicts that this should be possible with PC predicates but not with EC predicates. The prediction appears to be borne out:

-

(ii)

*The students each tried to visit one another.

-

(i)

I thank an anonymous reviewer for pointing out that a second lexical entry would be needed for object control; here, PRO should denote the addressee of the context. As the reviewer points out, the need to multiply the entries for PRO, and concomitantly to supply an account of the distribution of the two variants of PRO in subject versus object control, is a disadvantage of this type of approach.

Unanswered questions still remain concerning the phi-features on PRO under the property view: as discussed in footnote 13, it remains to be spelled out how embedded C inherits the phi-features of the controller. We nonetheless think that the property view has the advantage, given that it offers a mechanism for deleting the phi-features of the controller on PRO, irrespective of how these features come to be inherited by PRO in the first place.

I am grateful to an anonymous reviewer for prompting me to think more about the issues discussed in this section.

This semantics is incomplete in that it does not account for the observation that when remember takes a gerundive complement, it is obligatorily interpreted as reporting a memory as experienced ‘from the inside’ in the sense of Vendler (1979). This requirement is responsible for the following contrast, based on Higginbotham (2003):

-

(i)

I used to remember going to the movies when I was ten years old, but I no longer remember it.

-

(ii)

#I used to remember that I went to the movies when I was ten years old, but I no longer remember it.

-

(i)

References

Abusch, Dorit. 1997. Sequence of tense and temporal de re. Linguistics and Philosophy 20(1): 1–50.

Abusch, Dorit. 2004. On the temporal composition of infinitives. In The syntax of time, eds. Jacqueline Gueron and Jacqueline Lecarme, 27–53. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Anand, Pranav. 2006. De De Se. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, MIT.

Anand, Pranav, and Andrew Nevins. 2004. Shifty operators in changing contexts. Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 14: 20–37.

Bach, Emmon. 1979. Control in Montague grammar. Linguistic Inquiry 10: 515–531.

Barrie, Michael, and Christine Pittman. 2004. Partial control and the movement towards movement. Toronto Working Papers in Linguistics 22: 75–92.

Bennett, Michael, and Barbara Partee. 1972. Toward the logic of tense and aspect in English. Bloomington: Indiana University Linguistics Club.

Boeckx, Cedric, Norbert Hornstein, and Jairo Nunes. 2010. Control as movement. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Boskovic, Željko. 1996. Selection and the categorial status of infinitival complements. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 14: 269–304.

Boskovic, Željko. 1997. The syntax of nonfinite complementation: An economy approach. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Bowers, John. 2008. On reducing control to movement. Syntax 11: 125–143.

Chierchia, Gennaro. 1984. Topics in the syntax and semantics of infinitives and gerunds. Ph.D. dissertation, UMass, Amherst.

Chierchia, Gennaro. 1989. Structured meanings, thematic roles and control. In Properties, types and meanings II, eds. Gennaro Chierchia and Barbara Partee, 131–166. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Chierchia, Gennaro. 1990. Anaphora and attitudes de se. In Semantics and contextual expression, eds. Renate Bartsch, Johan van Benthem, and Peter van Emde Boas, 1–32. Dordrecht: Foris.

Clark, Robin L. 1990. Thematic theory in syntax and interpretation. London-New York: Routledge.

Dowty, David. 1977. Toward a semantic analysis of verb aspect and the English ‘imperfective’ progressive. Linguistic and Philosophy 1(1): 45–77.

Dowty, David. 1979. Word meaning and Montague grammar: The semantics of verbs and times in generative semantics and in Montague’s PTQ. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Dowty, David. 1985. On recent analyses of the semantics of control. Linguistics and Philosophy 8: 291–331.

Enç, Mürvet. 1991. On the absence of the present tense morpheme in English. Unpublished manuscript.

Grano, Thomas. 2011. Mental action and event structure in the semantics of try. Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 21: 426–443. Brunswick, NJ.

Grano, Thomas. 2012. Control and restructuring at the syntax-semantics interface. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Chicago.

Heim, Irene. 1992. Presupposition projection and the semantics of attitude verbs. Journal of Semantics 9: 183–221.

Heim, Irene. 2007. Person and number on bound and partially bound pronouns. Unpublished manuscript.

Higginbotham, James. 2003. Remembering, imagining, and the first person. In Epistemology of language, ed. Alex Barber, 496–533. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hintikka, Jaako. 1969. Semantics for propositional attitudes. In Philosophical logic, eds. John W. Davis and David J. Hockney, 21–45. Dordrecht: Reidel.

Hornstein, Norbert. 2003. On control. In Minimalist syntax, ed. Randall Hendrick, 6–81. Malden: Blackwell.

Jackendoff, Ray, and Peter Culicover. 2003. The semantic basis of control in English. Language 79: 517–556.

Landau, Idan. 2000. Elements of control: Structure and meaning in infinitival constructions. Dordrecht-Boston: Kluwer Academic.

Landau, Idan. 2003. Movement out of control. Linguistic Inquiry 34: 471–498.

Landau, Idan. 2004. The scale of finiteness and the calculus of control. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 22: 811–877.

Landau, Idan. 2006. Severing the distribution of PRO from case. Syntax 9: 153–170.

Landau, Idan. 2008. Two routes of control: evidence from case transmission in Russian. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 26: 877–924.

Landau, Idan. 2010. The explicit syntax of implicit arguments. Linguistic Inquiry 41: 357–388.

Landau, Idan. 2013a. Control in generative grammar: A research companion. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Landau, Idan. 2013b. A two-tiered theory of control. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Lebeaux, David. 1985. Locality and anaphoric binding. The Linguistic Review 4: 343–363.

Lewis, David. 1979. Attitudes de dicto and de se. Philosophical Review 88(4): 513–543.

Maier, Emar. 2009. Presupposing acquaintance: a unified semantics for de dicto, de re and de se belief reports. Linguistics and Philosophy 32: 429–474.

Maier, Emar. 2011. On the roads to de se. Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 21: 393–412.

Martin, Roger. 1996. A minimalist theory of PRO and control. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Connecticut.

Martin, Roger. 2001. Null case and the distribution of PRO. Linguistic Inquiry 32: 141–166.

Morgan, Jerry. 1970. On the criterion of identity for noun phrase deletion. Chicago Linguistic Society (CLS) 6: 380–389. Chicago, IL.

Ogihara, Toshiyuki. 1996. Tense, attitudes and scope. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic.

Ogihara, Toshiyuki. 2007. Tense and aspect in truth-conditional semantics. Lingua 117: 392–418.

Pearson, Hazel. 2013. The Sense of Self: Topics in the Semantics of De Se Expressions. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Harvard University.

Percus, Orin, and Uli Sauerland. 2003. Pronoun movement in dream reports. North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 33: 347–366. MIT, Cambridge.

Pesetsky, David. 1992. Zero Syntax II: an essay on infinitives. Unpublished manuscript.

Petter, Margaretha. 1998. Getting PRO under control. The Hague: Holland Academic Graphics.

Quine, Willard van Orman. 1956. Quantifiers and propositional attitudes. Journal of Philosophy 53: 177–187.

Reinhart, Tanya. 1990. Self-representation. Lecture delivered at Princeton conference on anaphora, October 1990, Ms.

Rodrigues, Cilene. 2007. Agreement and flotation in partial and inverse partial control configurations. In New horizons in the analysis of control and raising, eds. William D. Davies and Stanley Dubinsky, 213–229. Dordrecht: Springer.

Sauerland, Uli. 2003. A new semantics for number. Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 13: 258–275.

Schlenker, Phillipe. 1999. Propositional attitudes and indexicality: A cross-categorial approach. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, MIT.

Schlenker, Phillipe. 2003. A plea for monsters. Linguistics and Philosophy 26: 29–120.

Sharvit, Yael. 2003. Trying to be progressive: The extensionality of try. Journal of Semantics 20(4): 403–445.

Stephenson, Tamina. 2007. Towards a theory of subjective meaning. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, MIT.

Stephenson, Tamina. 2010a. Control in centred worlds. Journal of Semantics 27: 409–436.

Stephenson, Tamina. 2010b. Vivid attitudes: Centred situations in the semantics of remember and imagine. Semantics and Linguistic Theory (SALT) 20: 147–160.

Taylor, Barry. 1977. Tense and continuity. Linguistics and Philosophy 1: 199–220.

Uegaki, Wataru. 2011. Controller shift in centred-world semantics. Handout of talk given at workshop on Grammar of Attitudes. German Linguistic Society 33, University of Göttingen.

van Urk, Coppe. 2010. On obligatory control: A movement and PRO approach. Unpublished manuscript.

Vendler, Zeno. 1979. Vicarious experience. Revue de Métaphysique et de Morale 84: 161–173.

Vlach, Frank. 1981. The semantics of the progressive. In Syntax and semantics: Tense and aspect 14, eds. Philip J. Tedeschi and Annie Zaenen, 71–292. New York: Academic Press.

von Fintel, Kai. 1999. NPI licensing, Strawson entailment, and context dependency. Journal of Semantics 16: 97–148.

von Stechow, Arnim. 2002. Binding by verbs: Tense, person and mood under attitudes. Unpublished manuscript.

von Stechow, Arnim. 2003. Feature deletion under semantic binding. North East Linguistic Society (NELS) 33.

White, Aaron Steven, and Thomas Grano. 2014. An experimental investigation of partial control. In Proceedings of Sinn und Bedeutung 18, eds. U. Etxeberria, A. Falaus, and B. Leferman, 469–486.

Wilkinson, Robert. 1971. Complement subject deletion and subset relations. Linguistic Inquiry 2: 203–238.

Williams, Edwin. 1980. Predication. Linguistic Inquiry 11: 203–238.

Witkos, Jacek, and Anna Snarska. 2008. On partial control and parasitic PC effects. SKASE Journal of Theoretical Linguistics 5: 42–75.

Wurmbrand, Susanne. 1998. Infinitives. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, MIT.

Wurmbrand, Susanne. 2001. Infinitives: Restructuring and Clause structure. Berlin/New York: Mouton de Gruyter.

Wurmbrand, Susanne. 2002. Syntactic vs. semantic control. In Studies in comparative Germanic syntax: Proceedings from the 15th workshop on comparative Germanic syntax, eds. Jan-Wouter Zwart and Abraham Werner, 95–129. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Wurmbrand, Susanne. 2007. Infinitives are tenseless. Penn Working Papers in Linguistics 13(1): Penn Linguistics Colloquium (PLC) 30: 407–420.

Wurmbrand, Susanne. 2014. Tense and aspect in English infinitives. Linguistic Inquiry 45(3): 403–447.

Acknowledgements

This paper develops ideas originally presented in Chap. 6 of my Ph.D. dissertation (Pearson 2013). For helpful discussion I thank Gennaro Chierchia, Amy Rose Deal, Thomas Grano, Irene Heim, Norbert Hornstein, Manfred Krifka, Maria Polinsky, Jacopo Romoli, Uli Sauerland, Barbara Stiebels and audiences at the University of Maryland, NELS 43 and ZAS, Berlin. I am also grateful to three anonymous reviewers for extensive comments that significantly improved the manuscript. The research leading to these results has received funding from the People Programme (Marie Curie Actions) of the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP7 2007–2013) under grant agreement no 618871, and from the Bundesministerium für Bildung und Forschung (BMBF) (Grant Nr. 01UG0711).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Appendix

Appendix

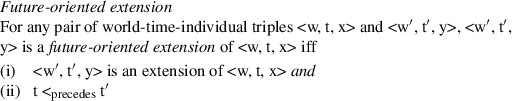

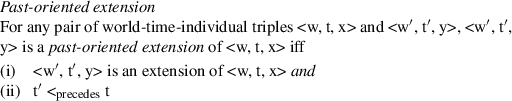

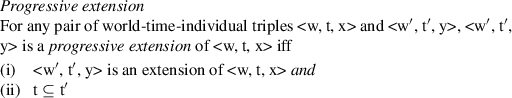

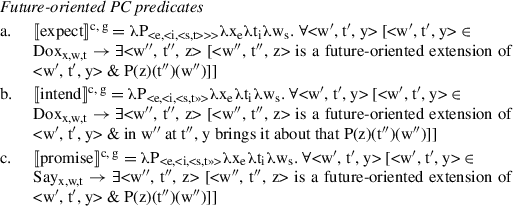

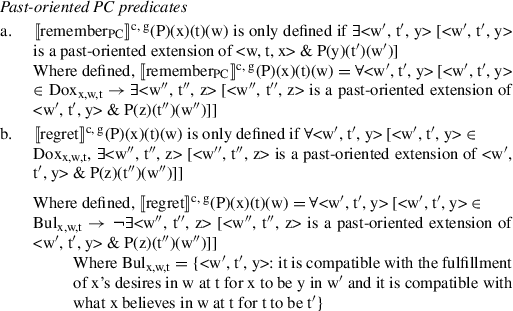

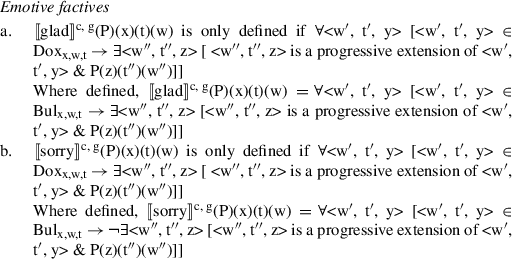

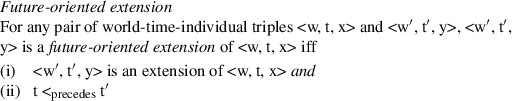

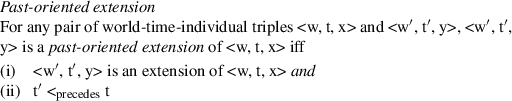

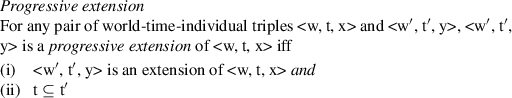

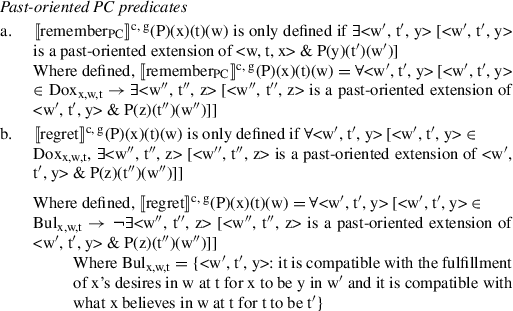

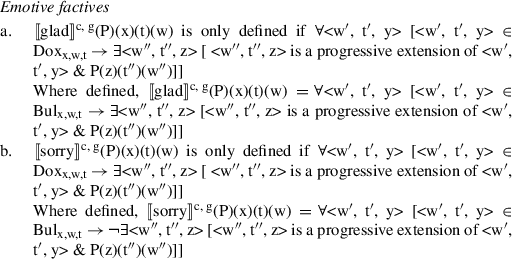

Our template semantics for partial control predicates is weak in that it permits the subjective ‘now’ of the attitude holder t′ to stand in any of a range of relations to the temporal coordinate t″ of an extension: t″ may be in the future with respect to t′, in the past with respect to t′, or it may include t′. We need a way to constrain this schema further in order to ensure that (i) future-oriented PC predicates do not tolerate past-oriented or progressive-like interpretations, (ii) past-oriented PC predicates do not tolerate future-oriented or progressive-like interpretations, and (iii) emotive factives do not tolerate future- or past-oriented interpretations. We can do this by defining three different classes of extension: future-oriented, past-oriented and progressive extensions.

-

(1)

-

(2)

-

(3)

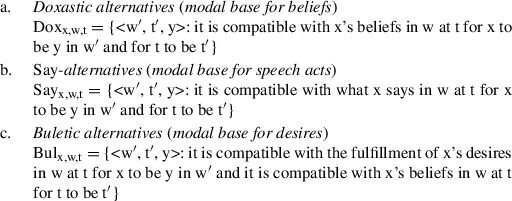

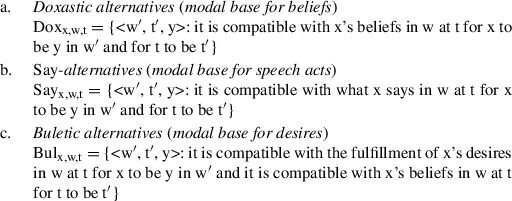

The semantics of a future-oriented PC predicate incorporates existential quantification over future-oriented extensions; that of a past-oriented PC predicate incorporates existential quantification over past-oriented extensions; and that of an emotive factive incorporates existential quantification over progressive extensions. Recall also that we are assuming that attitude predicates are universal quantifiers over modal bases such as the following:

-

(4)

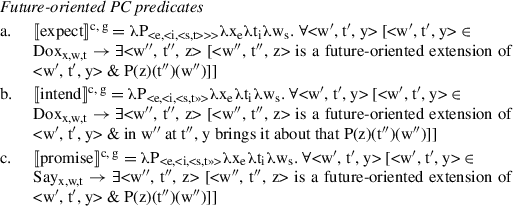

We can now provide complete sample lexical entries.

-

(5)

These entries capture the intuitions that (a) if Mary expects to go to the movies, then she has the belief, “I will go to the movies”, (b) if Mary intends to go to the movies, then she has the belief, “I will bring it about that I go to the movies”, and (c) if Mary promises to go to the movies then she performs the speech act, “I will go to the movies”.

-

(6)

Mary remembers going to the movies is only felicitous if Mary went to the movies at some point in the past. It reports that she believes that she went to the movies. Mary regrets going to the movies carries the same presupposition, and reports that for each of Mary’s buletic alternatives <w′, t′, y>, there is no time earlier than t′ at which y went to the movies in w′.Footnote 25

-

(7)

Mary was glad to go the movies and Mary was sorry to go to the movies both presuppose that Mary believes that she went to the movies. The former asserts that for every <w′, t′, y> such that it is desirable to Mary for her to be y in w′ and t′ is a candidate of hers for the actual time, there is a time that includes t′ such that y goes to the movies in w′.Footnote 26 The latter asserts that at every such <w′, t′, y> there is no time that includes t′ such that y goes to the movies in w′ at t′. We leave it as an exercise to the reader to construct parallel partial control examples.

Notice that the progressive-like meaning component of emotive factives is not identical to the semantics of the overt progressive morpheme. For one thing, the former appeals to an inclusion relation rather than a proper inclusion relation between time intervals. Moreover, in Dowty (1979) and subsequent literature the semantics of the progressive is augmented with an appeal to modal quantification to account for the possibility of an event marked with the progressive being unrealized in the actual world, as in John was writing a letter to Mary when a friend called and he forgot to finish it. Some data pointed out to us by an anonymous reviewer suggest that it is undesirable to incorporate this into the definition of progressive extension. In a situation where John didn’t get round to finishing his letter it is false (or at least infelicitous) to say John was glad to write a letter to Mary; unlike with the overt progressive, the event in question must be realized in the actual world.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Pearson, H. The semantics of partial control. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 34, 691–738 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-015-9313-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-015-9313-9