Abstract

One function of prosodic phrasing is its role in aiding in the recoverability of syntactic structure. In recent years, a growing body of work suggests it is possible to find concrete phonetic and phonological evidence that recursion in syntactic structure is preserved in the prosodic organization of utterances (Ladd 1986, 1988; Kubozono 1989, 1992; Féry and Truckenbrodt 2005; Wagner 2005, 2010; Selkirk 2009, 2011; Ito and Mester 2013; Myrberg 2013). This paper argues that the distribution of phrase-level phrase accents in Connemara Irish provides a new type of evidence in favour of this hypothesis: that, under ideal conditions, syntactic constituents are mapped onto prosodic constituents in a one-to-one fashion, such that information about the nested relationships between syntactic constituents is preserved through the recursion of prosodic domains. Through an empirical investigation of both clausal and nominal constructions, I argue that the distribution of phrasal phrase accents in Connemara Irish can be used as a means of identifying recursive bracketing in prosodic structure.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As will be discussed below, I refer to LH and HL tones as “phrase accents” following Grice et al. (2000). Phrase accents behave like boundary tones because they play a role in demarcating the edges of prosodic constituents, but unlike boundary tones in the traditional sense of the term (Bruce 1977; Pierrehumbert 1980), they align with the stressed syllable of the word rather than with the absolute edge of the prosodic constituent. Other examples of edge-dependent phrase accents may include the post-focal accent in European Portuguese (Frota 2000) and the initiality accent in Stockholm Swedish (Bruce 1977; Myrberg 2010).

The data and much of the analysis reported in the present paper build on Elfner (2011, 2012, 2013). However, the data discussed in the present paper represent only a subset of those discussed in Elfner (2012). Space constraints prevent me from discussing the full range of data in the present paper, but interested readers are referred to that work for additional examples of pitch tracks, as well as more detailed discussion of tonal phenomena for syntactic configurations not discussed in this paper.

The same corpus was used in Elfner (2012). For further details, please refer to this work.

Note, however, that one participant, AN, reports having lived in England from ages 5–9.

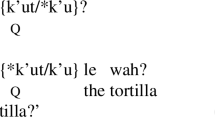

The codes appearing below the pitch tracks are a reference to the date they were recorded on, a three-digit number indicating the trial number, the participant’s initials (e.g. MN, YF), and the repetition number (e.g. e1 meaning repetition 1).

In all pitch tracks included in this paper, Tier 1 indicates the tonal transcription, while Tier 2 represents a syllable-by-syllable phonemic transcription in IPA, including stress assignment. Tier 3 represents word-level transcription in Irish orthography, while Tiers 4 and 5 indicate the English gloss and translation, respectively.

An alternative analysis is that the second H tone is downstepped relative to the first, which would also contribute to the observed declination of the H tone plateau.

Note that Dalton and Ní Chasaide assume a different system of intonational analysis, the IViE system (Grabe et al. 1998, 2001). The LH accent proposed here corresponds to their H*(+L) prenuclear accent, and the HL accent to their H*+L nuclear accent. The IViE system explicitly rejects accents of the form L*+H, hence their (superficially) different interpretation of the LH accent.

That is to say, there is no evidence offered in this paper that would require a categorical distinction between φ and the intonational phrase (ɩ). This is not a claim that such evidence does not exist or that such an analysis would not be possible, but rather that it has yet to be systematically argued that (for Irish) that a separate ɩ category is necessary, i.e. that there are distinct prosodic phenomena that pattern within the prosodic domain ɩ. Under the recursion-based analysis offered here, it is possible that the category φMax could plausibly be reanalysed as the domain traditionally associated with ɩ-level phenomena. The implications of this assumption are left for future research.

An anonymous reviewer observes that the account proposed in this paper also departs from much recent work which proposes that there is a relationship between cyclic or phase-based spell-out and prosodic phrasing, including Wagner (2005, 2010), as well as many others (e.g. Dobashi 2004, 2009, 2010; Ishihara 2007; Kratzer and Selkirk 2007; Kahnemuyipour 2009). As will become evident in the discussion to follow, the analysis of phrase accent distribution proposed here relies on the assumption that the structure of the entire sentence is available at Spell-Out, rather than only a phase or cyclic chunk. However, the analysis proposed here is not inherently incompatible with a phase-based or cyclic approach in which, for example, information about the structure of already spelled-out material remains accessible, or where spelled-out phases are assembled in a hierarchical rather than linear manner.

The internal structure of branching DPs in Irish will be discussed in more detail in Section 5.

McCloskey (2009, 2011) proposes that the verb raises through ν, T, and ends up in the head of the polarity phrase ΣP. This proposal is based on the ability of the verb to convey information about polarity in VP ellipsis, where the bare verb is used in place of polarity particles (like yes and no) in answer to yes/no questions. It is also clear that if (some) subjects raise to Spec, TP (McCloskey 2001), the verb must then occupy a position above this projection. I will assume, following McCloskey, that this projection is ΣP; however, it is not crucial to this paper what the label of this projection is.

In order for analyses assuming the copy theory of movement (Chomsky 1993) to remain compatible with the assumptions made here, we would need to assume that copies are deleted before they are sent to PF, or at least before prosodic domains are assigned. Deleted copies would then be expected to behave as phonologically null elements, because they would have no phonological exponent at spell-out.

Following standard practices in prosodic theory, I use the symbol φ to represent a phrase-level prosodic domain (as defined in (3)) and ω to represent a prosodic word-level domain, which I assume roughly correspond to lexical words in the syntax. I follow Selkirk (1995) in assuming a basic distinction between lexical words (V, N, Adj, etc.), which are by default parsed as prosodic words ω, and function words (Det, P, Prn, etc.), which are not. While the issues surrounding the prosodic status of function words in Irish are more complicated than can be discussed at present (though see Bennett et al. 2015a, 2015b), this distinction can be upheld for the majority of cases, including all of those discussed in this paper. For the purposes of this paper, I will assume that function words like determiners and prepositions are proclitic on the prosodic word which immediately follows it (following Bennett et al. 2015a, 2015b).

As will be discussed in Section 3.3, this point will become important for the analysis of the distribution of the LH accent in CI.

An anonymous reviewer suggests that the failure for adjectives to be parsed as prosodic phrases may be part of a more general unsolved puzzle in syntax-prosody mapping, such that adjectives do not project as prosodic phrases while sentential adverbs do. If this is the case in CI, this would suggest that the reason that APs are not parsed as φ is not due to eurhythmic constraints, as the analysis sketched above would suggest. At this point, I do not have sufficient data regarding the prosodic status of sentential adverbs in CI, but it would make an interesting topic for future research.

Of the six possible natural classes of recursion-based projections, Ito and Mester (2013) provide typological evidence for the maximal, minimal and maximal/minimal projections, in addition to the evidence provided here for the non-minimal projections. To the best of my knowledge, there is currently no proposal that would require reference to either the intermediate projections (κ[−max,−min]) or to the non-maximal projections (κ[−max]), although such distinctions are predicted typologically.

As mentioned above, the discussion in the present paper is limited, and as such, only a subset of examples is discussed. See Elfner (2012) for a wider range of examples and structures.

In the following representation, I have represented the preposition in the indirect object as being prosodically dependent on the following noun (see footnote 16).

As in other languages, certain classes of adverbs in Irish may right-adjoin to νP (McCloskey 1996; Ernst 2002). These are not predicted by the proposed system to behave prosodically differently than the VP-internal PP in the representation in (17a): they will form a (recursive) constituent with the object, with the possibility that they will be parse as φ themselves if they meet the binarity requirement. However, other classes of adverbs that attach at different locations in the tree (e.g. adjoined to TP or higher; left adjoined to νP) may make different predictions in terms of prosodic phrasing. Unfortunately, I do not at present have access to data that would test for these differences and these questions are left for future research. Note that adverbs are almost always found in sentence-final position in Irish; and only a limited class may intervene between subject and object (McCloskey 1996; Adger 1997).

Note that sequences of two H tones (as in the noun-adjective sequence in the subject of the above sentence) are often downstepped, resulting in a second H tone that is lower than the one preceding it and obscuring the expected H tone plateau. As discussed above, declination also plays a role in producing this pattern, especially in words with several unstressed syllables.

Note that even though there is a slight rise in F0 on blathanna ‘flowers’, this does not indicate the presence of an LH phrase accent. As discussed in Section 3.1, the HL accent reaches its peak in the stressed vowel, then shows a gradual decline through to the end of the word. The rise in this pitch track occurs only in the onset of the initial syllable.

While the corpus includes data from a total of seven native speakers, only six speakers are discussed in this section. The data from one of these speakers (MF) were considered in the rest of the paper but excluded from this section because the results were not directly comparable in quantitative terms (i.e. a different set of sentences and sentence types were recorded).

I use the term non-final subject rather than simply subject because the subjects considered include only branching subjects that are followed either by a direct object or an adjunct. This count excludes branching subjects that are final in the sentence, as in intransitive sentences without any adjuncts. The reason for this distinction is that these sentence-final branching subjects are predicted to behave differently from non-final branching subjects by not bearing LH phrase accents: unlike non-final branching subjects, final branching subjects are not leftmost in φNon-min. This does appear to be the case; see Elfner (2012) for some preliminary results.

For MN but not for other speakers, many of the tokens with an interpolated rise on the final DP noun were followed by a vowel-initial adjective that was produced with an initial glottal stop (for example, the pitch track produced by MN in (1)). Because glottal stops may raise F0, it is possible that these interpolated rises are due to this segmental effect in many of these cases. Under this scenario, the realization of an accentless noun as having a flat F0 contour or an interpolated rise (or fall) may in part depend on segmental content.

In some sentences, it is clear that the HL is indeed an HL accent, and that the pattern is indicative of an alternate phrasing that is often employed by NC but not by other speakers.

Note that the arguments that have been proposed in the cited work in favour of an N-raising account for Irish and other Celtic languages are based on the assumption that adjectives in these languages, while post-nominal, occur in the same order as in languages like English (i.e. not in the ‘mirror-image’ order found in Hebrew, for example). However, Willis (2006:1816), citing Thomas (1996), observes that this is not universally true of adjective order in Welsh: for example, adjectives of quality tend to precede adjectives of age and colour in English (quality > age > colour), but follow them in Welsh (age > colour > quality). An example of this type in Irish can be seen in (28b), and to the best of my knowledge (based on my own informal fieldwork on adjective order Irish) these observations hold in Irish as well, and could ultimately provide evidence against a strict N-raising analysis for Irish, along the lines Willis (2006) for Welsh.

The data reported in this paper for complex DP structures is relatively limited, with further investigation of DP structures left to future research (though see Elfner 2011, 2012, 2013 for some discussion of possessive constructions and relative clauses). For instance, I do not have access to prosodic data relating to the behaviour of DPs with numerals, intensifiers, and complements to N, and only limited data for DPs with overt determiners and prepositions. In the case of determiners and prepositions, these appear to behave consistently as proclitics to the immediately following ω (see footnote 16): their overt presence in a DP structure (as in (29)) does not affect the status of φ as minimal or non-minimal, as argued in Elfner (2012). As for other structures, it is not possible to move beyond speculation with respect to their prosodic character, and these questions must be left for future research.

Note that the maximal projection DP is not mapped onto a φ domain in addition to that which is projected by FP. As discussed in Section 3.2, we can make the assumption following Nespor and Vogel (1986) and others, that phonologically null elements and traces do not participate in the formation of prosodic domains; it is a logical step to assume, in a framework like the one put forth in this paper, that maximal projections dominating the same set of phonologically overt elements (like DP and FP, when D is null) project only a single prosodic domain, φ. If D is instead overt, the determiner, as a function word, will behave as a proclitic onto the following N, negating the need for the DP to project its own φ domain. If other elements project between D and FP (i.e. elements which preceded the noun, like numerals), it is predicted that these elements will project additional φ domains if the element is parsed as a prosodic word. This may be the case with numerals, whose prosodic character in Irish is at this stage unclear, but unfortunately, I do not have access to data at present that would confirm this prediction.

Note that although the analysis proposed here relies to a certain extent on a particular interpretation of the syntactic structure of DPs, it is in principle consistent with any syntactic derivation that results in the surface constituent structure [N[AA]], and not obviously consistent with any derivation resulting in [[NA]A]. For example, if we were to reject (or partially reject) the N-raising analysis on the basis of the observations in footnote 30 that mirror-image adjective ordering is (sometimes) possible in Irish as in Welsh, a plausible alternative would be to adopt an NP-raising approach (Cinque 1996) as proposed for languages like Hebrew (Sichel 2000; Shlonsky 2004) (although cf. Willis 2006, who rejects this approach for Welsh on both empirical and theoretical grounds). While it is not possible to sketch out a full analysis here, it is important to note that an NP-raising approach appears to make different empirical predictions with respect to prosodic phrasing as compared to the N-raising account assumed here: provided that adjectives are adjoined to NP, a pied-piping analysis involving NP-raising would result in a surface structure [[NA]A], which would be pronounced as [[LHN AHL] AHL]. The data reported in this paper would appear to speak against this type of analysis, although a more comprehensive and systematic study of the prosody of adjective ordering in Irish would help to shed light on this matter.

Note that a possible alternative prosodic analysis, in which N and two adjectives is parsed as a tertiary (non-recursive) prosodic domain (NAA) makes a slightly different prediction. Because the tertiary structure is not recursive, it is not inherently non-minimal, meaning that it can only receive an LH accent when it is itself dominated by a φ in which it is leftmost (e.g. in subject position of a transitive sentence). If it is not (e.g. in object position of a transitive sentence), it is predicted to behave like the NA objects in not bearing an LH accent. As can be seen in (34), this is not the case: there is a clear LH phrase accent on the noun, even when the construction occurs in object position. This pitch track therefore supports the recursive analysis assumed here.

On dathúil ‘handsome’, the H target on HL, while obscured by the obstruent [d], is again downstepped with respect to the preceding H, on the LH accent of rúnaí ‘secretary’. On bána ‘white.pl’, the final small increase in F0 is likely the result of the glottal stop at the beginning of áille ‘beautiful.pl’.

In this particular example, the sentence is preceded by a sentential adverb inné ‘yesterday’. For this speaker, the adverb phrases together with the verb, which accounts for the presence of the HL accent on the verb (as well as the LH on inné). This example is included here because the phrasing of the verb does not appear to affect the tonal patterns observed on the subject, which is the purpose of the example.

Note that there is a slight dip in F0 on the adjective banúla ‘lady-like.pl’. This appears to coincide with the segment [l], though it remains unclear why this occurs (this was also observed in other recordings in the corpus). There is also a fall in F0 on málaí ‘bags’. It is unclear whether this fall indicates the presence of an HL phrase accent (which would indicate an atypical phrasing of the final object) or whether this is a property of this particular utterance or perhaps this particular speaker (note that a similar pattern is also observed in (40), which was uttered by the same speaker).

Note the presence of a pause between the subject and object. It has been observed (Bennett 2008) that such pauses occur in natural speech, and do not (necessarily) indicate a disfluency. This pause may also be seen in the pitch track (40).

In Section 3.2, it was proposed that the failure for APs to be parsed prosodically as φ could be accounted for with reference to a Binary-Minimum constraint, which would seem to support an indirect reference approach. However, it was also noted that this apparent “mismatch” could plausibly also be accounted for in syntactic terms, which would be compatible with a direct reference approach.

Note that we are, as in the case of the APs discussed in Section 3, required to assume that the non-branching subject noun is parsed prosodically as a minimal projection (ω) rather than as a φ, despite being dominated by the DP/NP maximal projection. As before, this may be explained in either prosodic terms (resulting from Binary-Minimum) or in syntactic terms.

Note that the F0 peak for the HL accent on múinteoirí ‘teachers’ is earlier than expected, with most of the fall in pitch occurring before the end of the first syllable. This might be the result of the phonological deletion of the second of the adjacent H peaks or fusion of the two H tones (from the concatenation of LH and HL): unlike previous cases discussed in this paper, there does not appear to be any downstep between these two peaks, as appears to be common with adjacent H tones in CI. It is plausible that instead of employing downstep to distinguish the adjacent H tones, the second H tone target is deleted instead, which might lead to an early fall toward the L target. It is unclear at present what conditions the differential phonological treatment of adjacent H tones (deletion vs. downstep); however, given that both deletion and fusion are plausible phonological repairs for a tonal OCP violation (Meyers 1997), it seems unlikely that this example is problematic for the proposed prosodic analysis. Note also that there is a break between the subject and object: as described in footnote 38, these pauses are also found in natural speech and do not appear to indicate a disfluency.

This assumption raises the issues of when in the course of syntactic spell-out speakers have access to phonological and prosodic information. This is an interesting (and large) topic, but unfortunately beyond the scope of this paper.

This is not to preclude the possibility that such arguments also exist for Irish.

One way to ensure that candidate (d) be chosen as optimal is to employ a prosodic markedness constraint like MaximalBinarity-φ, which would prefer candidates which φ constituents are maximally binary. If this constraint also outranks NonRec, candidate (d) would then win over candidate (c). However, adding this constraint introduces new problems to the analysis. For example, MaxBin-φ would not be able to choose between candidate (d) and a similar candidate showing the phrasing ((V (DP1)) (DP2)). Additional constraints would still be needed to distinguish between these candidates.

However, I will not attempt to sketch out alternative analyses of the CI data assuming edge-alignment, strict layering, or other alternative accounts here. The purpose of this paper is not to argue that the recursion-based analysis of phrase accent distribution in CI is the only possible analysis of the CI data; rather, I wish to show that the account proposed here provides an elegant account of a new set of data, and that there are several advantages to adopting a theory of prosodic phrasing that uses recursion.

What is not discussed here is just how restricted this set of prosodic categories needs to be. Selkirk (2011), as well as Ito and Mester (2013), assumes that there are three basic prosodic categories: ɩ, φ, and ω. In this paper, I have assumed a distinction between just two levels, φ and ω, with no evidence presented that would bear on the presence of a third category ɩ. An even more radical proposal would see no categorical distinction between prosodic categories at all, with different levels of prosodic boundary strength responsible for demarcating what would appear to be different “types” of prosodic categories, along the lines of that proposed in Wagner (2005, 2010). It is hoped that this question will be addressed in future research.

References

Adger, David. 1997. VSO order and weak pronouns in Goidelic Celtic. Canadian Journal of Linguistics 42: 9–29.

Beckman, Mary, and Janet Pierrehumbert. 1986. Intonational structure in English and Japanese. Phonology 3: 255–309.

Bennett, Ryan. 2008. Donegal Irish and the syntax/prosody interface.

Bennett, Ryan, Emily Elfner, and James McCloskey. 2015a, to appear. Lightest to the right: an apparently anomalous displacement in Irish. Linguistic Inquiry.

Bennett, Ryan, Emily Elfner, and James McCloskey. 2015b, to appear. Pronouns and prosody in Irish. In 14th International Congress of Celtic Studies. Dublin: Institute for Advanced Studies.

Berg, Rob, Carlos van den Gussenhoven, and Toni Rietveld. 1992. Downstep in Dutch: implications for a model. In Laboratory phonology II: gesture, segment, prosody, eds. Gerard J. Docherty and D. Robert Ladd, 335–359. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Blankenhorn, V. S. 1981a. Intonation in Connemara Irish: a preliminary study of kinetic glides. Studia Celtica 16(17): 259–279.

Blankenhorn, V. S. 1981b. Pitch, quantity and stress in Munster Irish. Éigse 18: 225–250.

Boersma, Paul, and David Weenink. 2007. Praat: doing phonetics by computer (version 4.5.1.5) [computer program]. Available online accessed.

Bondaruk, Anna. 1994. Irish as a pitch accent language (Connemara dialect). In Focus on language, eds. Edmund Gussmann and Henryk Kardela, 27–48. Lublin: Maria Curie-Sklodowska University Press.

Bondaruk, Anna. 2004. The inventory of nuclear tones in Connemara Irish. Journal of Celtic Linguistics 8: 15–47.

Bruce, Gosta. 1977. Swedish word accents in sentence perspective. Lund: Gleerup.

Chomsky, Noam. 1970. Remarks on nominalization. In Reading in English transformational grammar, eds. Roderick Jacobs and Peter Rosenbaum, 184–221. Waltham: Ginn.

Chomsky, Noam. 1993. A minimalist program for linguistic theory. In The view from building 20, eds. Kenneth Hale and Samuel Jay Keyser. Vol. 20, 1–52. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam. 1995. The minimalist program. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Chung, Sandra, and James McCloskey. 1987. Government, barriers and small clauses in Modern Irish. Linguistic Inquiry 18: 173–237.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 1994. On the evidence for partial N-movement in the Romance DP. In Paths towards universal grammar. Studies in honor of Richard S. Kayne, eds. Guglielmo Cinque, Jan Koster, Jean-Yves Pollock, Luigi Rizzi, and Raffaella Zanuttini, 85–110. Washington: Georgetown University Press.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 1996. The ‘antisymmetric’ programme: theoretical and typological implications. Journal of Linguistics 32: 447–464.

Dalton, Martha, and Ailbhe Ní Chasaide. 2005a. Peak timing in two dialects of Connaught Irish. In Interspeech: the 9th European Conference on Speech Communication and Technology, Lisbon.

Dalton, Martha, and Ailbhe Ní Chasaide. 2005b. Tonal alignment in Irish dialects. Language and Speech, 441–464.

de Bhaldraithe, Tomás. 1945. The Irish of Cois Fhairrge, Co. Galway. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies.

Dobashi, Yoshihito. 2004. Multiple spell-out, label-free syntax, and PF-interface. Explorations in English Linguistics 19: 1–47.

Dobashi, Yoshihito. 2009. Multiple spell-out, assembly problem, and syntax-phonology mapping. In Phonological domains: universals and deviations, eds. Janet Grijzenhout and Baris Kabak, 195–220. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Dobashi, Yoshihito. 2010. Computational efficiency in the syntax-phonology interface. The Linguistic Review 27: 241–260.

Elfner, Emily. 2011. Recursive phonological phrases in Conamara Irish. In West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL), eds. Mary Byram Washburn, Sarah Ouwayda, Chouying Ouyang, Bin Yin, Canan Ipek, Lisa Marston, and Aaron Walker. Vol. 28.

Elfner, Emily. 2012. Syntax-prosody interactions in Irish. Doctoral dissertation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst.

Elfner, Emily. 2013. Recursivity in prosodic phrasing: evidence from Conamara Irish. In The North East Linguistic Society (NELS), eds. Seda Kan, Claire Moore-Cantwell, and Robert Staubs. Vol. 40, 191–204. Amherst: GLSA.

Ernst, Thomas. 2002. The syntax of adjuncts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Féry, Caroline. 2011. German sentence accents and embedded prosodic phrases. Lingua 121: 1906–1922.

Féry, Caroline, and Fabian Schubö. 2010. Hierarchical prosodic structures in the intonation of center-embedded relative clauses. The Linguistic Review 27: 293–317.

Féry, Caroline, and Hubert Truckenbrodt. 2005. Sisterhood and tonal scaling. Studia Linguistica 59: 223–243.

Frota, Sonia. 2000. Prosody and focus in European Portuguese: phonological phrasing and intonation. New York: Garland.

Ghini, Marco. 1993. Phi-formation in Italian: a new proposal. Toronto Working Papers in Linguistics 12: 41–78.

Grabe, Esther, Francis Nolan, and Kimberley Farrar. 1998. IViE—a comparative transcription system for intonational variation in English. Paper presented to the proceedings of the 5th international conference on spoken language processing, Sydney, Australia.

Grabe, Esther, Brechtje Post, and Francis Nolan. 2001. Modeling intonational variation in English. The IViE system. Paper presented to the proceedings of prosody 2000, Poznan, Poland.

Green, Anthony Dubach. 1996. Stress placement in Munster Irish. In The Chicago Linguistic Society (CLS), Vol. 32. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

Green, Antony Dubach. 1997. The prosodic structure of Irish, Scots Gaelic, and Manx. Cornell University.

Grice, Martine, D. Robert Ladd, and Amalia Arvaniti. 2000. On the place of phrase accents in intonational phonology. Phonology 17: 143–185.

Guilfoyle, Eithne. 1988. Parameters and functional projection. In The North East Linguistic Society (NELS), eds. James Blevins and Juli Carter. Vol. 18, 193–207. Amherst: GLSA.

Haider, Hubert. 1993. Deutsche Syntax – generativ. Vorstudien zur Theorie einer projektiven Grammatik. Tübingen: Gunter Narr.

Ishihara, Shinichiro. 2007. Major phrase, focus intonation, and multiple spell-out. The Linguistic Review 24: 137–167.

Ito, Junko, and Armin Mester. 1992. Weak layering and word binarity. In A new century of phonology and phonological theory. A Festschrift for Professor Shosuke Haraguchi on the occasion of his sixtieth birthday, eds. Takeru Honma, Masao Okazaki, Toshiyuki Tabata, and Shin-ichi Tanaka, 26–65. Tokyo: Kaitakusha.

Ito, Junko, and Armin Mester. 2007. Prosodic adjunction in Japanese compounds. MIT Working Papers in Linguistics 55: 97–111.

Ito, Junko, and Armin Mester. 2010. The onset of the prosodic word. In Phonological argumentation: essays on evidence and motivation, ed. Steve Parker. London: Equinox.

Ito, Junko, and Armin Mester. 2012. Recursive prosodic phrasing in Japanese. In Prosody matters, eds. Toni Borowsky, Shigeto Kawahara, Takahito Shinya, and Mariko Sugahara. London: Equinox.

Ito, Junko, and Armin Mester. 2013. Prosodic subcategories in Japanese. Lingua 124: 20–40.

Jackendoff, Ray. 1977. X-bar-Syntax: a study of phrase structure. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Kahnemuyipour, Arsalan. 2009. The syntax of sentential stress. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Kratzer, Angelika, and Elisabeth Selkirk. 2007. Phase theory and prosodic spellout: the case of verbs. The Linguistic Review 24: 93–135.

Kubozono, Haruo. 1989. Syntactic and rhythmic effects on downstep in Japanese. Phonology 6: 39–67.

Kubozono, Haruo. 1992. Modeling syntactic effects on downstep in Japanese. In Laboratory phonology II: gesture, segment, prosody, eds. Gerard Docherty and D. Robert Ladd, 368–387. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Ladd, D. Robert. 1986. Intonational phrasing: the case for recursive prosodic structure. Phonology 3: 311–340.

Ladd, D. Robert. 1988. Declination ‘reset’ and the hierarchical organization of utterances. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America 84: 530–544.

Larson, Richard. 1988. On the double object construction. Linguistic Inquiry 19: 335–392.

Longobardi, Giuseppe. 2001. The structure of DPs: some principles, parameters, and problems. In The handbook of contemporary syntactic theory, eds. Mark Baltin and Chris Collins, 562–603. Malden: Blackwell.

McCawley, James D. 1968. The phonological component of a grammar of Japanese. The Hague: Mouton.

McCloskey, James. 1991. Clause structure, ellipsis and proper government in Irish. Lingua 85: 259–302.

McCloskey, James. 1996. Subjects and subject positions in Irish. In The syntax of the Celtic languages: a comparative perspective, eds. Robert Borsley and Ian Roberts, 241–283. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McCloskey, James. 2001. On the distribution of subject properties in Irish. In Objects and other subjects, eds. William D. Davies and Stanley Dubinsky, 157–192. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

McCloskey, James. 2009. The syntax of clauses in Irish. Paper presented at formal approaches to Celtic linguistics mini-course, 23–27 March.

McCloskey, James. 2011. The shape of Irish clauses. In Formal approaches to Celtic linguistics, ed. Andrew Carnie. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Meyers, Scott. 1997. OCP effects in optimality theory. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 15: 847–892.

Myrberg, Sara. 2010. The intonational phonology of Stockholm Swedish. Doctoral dissertation, Stockholm University.

Myrberg, Sara. 2013. Sisterhood in prosodic branching. Phonology 30: 73–124.

Nespor, Marina, and Irene Vogel. 1986. Prosodic phonology. Dordrecht: Foris.

Ó Siadhail, Mícheál. 1989. Modern Irish: grammatical structure and dialectal variation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

O’Rahilly, Thomas F. 1932/1979. Irish dialects past and present. Dublin: Dublin Institute of Advanced Studies.

Pak, Majorie. 2008. The postsyntactic derivation and its phonological reflexes. Doctoral dissertation, University of Pennsylvania.

Pierrehumbert, Janet. 1980. The phonology and phonetics of English intonation. Doctoral dissertation, MIT.

Pierrehumbert, Janet, and Mary Beckman. 1988. Japanese tone structure. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Prince, Alan, and Paul Smolensky. 1993/2004. Optimality theory: constraint interaction in generative grammar. Rutgers University RuCCS Technical Report.

Roberts, Ian. 2005. Principles and parameters in a VSO language: a case study in Welsh. New York: Oxford University Press.

Rouveret, Alain. 1994. Syntaxe du Gallois. Paris: CNRS Éditions.

Selkirk, Elisabeth. 1978. On prosodic structure and its relation to syntactic structure. In Nordic prosody, ed. Thorstein Fretheim, 111–140. Trondheim: TAPIR.

Selkirk, Elisabeth. 1986. On derived domains in sentence phonology. Phonology Yearbook 3: 371–405.

Selkirk, Elisabeth. 1995. The prosodic structure of function words. In Papers in Optimality Theory, eds. Jill Beckman, Laura Walsh Dickey, and Suzanne Urbanczyk, 439–470. Amherst: GLSA.

Selkirk, Elisabeth. 2009. On clause and intonational phrase in Japanese: the syntactic grounding of prosodic constituent structure. Gengo Kenkyū 136: 35–73.

Selkirk, Elisabeth. 2011. The syntax-phonology interface, 2nd edn. In The handbook of phonological theory, eds. John Goldsmith, Jason Riggle, and Alan Yu.

Selkirk, Elisabeth, and Tong Shen. 1990. Prosodic domains in Shanghai Chinese. In The phonology-syntax connection, eds. Sharon Inkelas and Draga Zec, 313–337. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Shlonsky, Ur. 2004. The form of Semitic noun phrases. Lingua 114: 1465–1526.

Sichel, Ivy. 2000. Evidence for DP-internal remnant movement. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS), eds. Masako Hirotani, Andries Coetzee, Nancy Hall, and Ji-yung Kim. Vol. 30, 568–581. Amherst: GLSA.

Sproat, Richard, and Chi-Lin Shih. 1991. The crosslinguistic distribution of adjective ordering restrictions. In Interdisciplinary approaches to language: essays in honor of S. Y. Kuroda, eds. Carol Georgopoulos and Roberta Ishihara, 565–594. Dordrecht: Kluwer.

Stephens, J. 1993. The syntax of noun phrases in Breton. Journal of Celtic Linguistics 2: 129–150.

The Christian Brothers. 2004. New Irish grammar. Dublin: C J Fallon.

Thomas, Peter Wynn. 1996. Gramadeg y Gymraeg. Cardiff: Gwasg Prifysgol Cymru.

Truckenbrodt, Hubert. 1995. Phonological phrases: their relation to syntax, focus, and prominence. Doctoral dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Truckenbrodt, Hubert. 1999. On the relation between syntactic phrases and phonological phrases. Linguistic Inquiry 30: 219–256.

Wagner, Michael. 2005. Prosody and recursion. Doctoral dissertation, MIT.

Wagner, Michael. 2010. Prosody and recursion in coordinate structures and beyond. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 28: 183–237.

Willis, David. 2006. Against N-raising and NP-raising analyses of Welsh noun phrases. Lingua 116: 1807–1839.

Acknowledgements

Above all, I would like to like to thank the Irish speakers who contributed to this project, Norita Ní Chartúir, Fiona Ní Fhlaithearta, Breda Ní Mhaoláin, Áine Ní Neachtain, Máire Uí Fhlatharta, Baba Uí Loingsigh, and especially Michael Newell and Yvonne Ní Fhlatharta, who met with me on several occasions. I am also indebted to Máire Ní Chiosáin and to the staff at the Acadamh na hOllscolaíochta Gaeilge for help with recruiting speakers and setting up recording sessions. Many thanks are due to Jim McCloskey, Lisa Selkirk and Michael Wagner for providing feedback and comments on this paper in its various stages, as well as to the editor, Marcel den Dikken, and three anonymous reviewers for NLLT whose comments tightened and improved the paper immensely. Additionally, I am grateful for discussions with Ryan Bennett, Amelie Dorn, Gorka Elordieta, Mark Feinstein, John Kingston, Seunghun Lee, John McCarthy, Maria O’Reilly and many other colleagues and audience members at UMass Amherst, McGill, UC Santa Cruz, the University of Calgary, ZAS Berlin, and Trinity College Dublin. Finally, I would like to acknowledge financial support from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (Doctoral Fellowship 752-2006-1349 and Postdoctoral Fellowship 756-2011-0285), the National Science Foundation (NSF grant BCS-1147083 to Elisabeth Selkirk), and from the University of Massachusetts Amherst Linguistics Department.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Elfner, E. Recursion in prosodic phrasing: evidence from Connemara Irish. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 33, 1169–1208 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-014-9281-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-014-9281-5